Edward Feser's Blog, page 23

June 12, 2022

Economic and linguistic inflation

F. A. Hayek’s classic paper “The Use of Knowledge in Society” famously argued that prices generated in a market economy function to transmit information that economic actors could not otherwise gather or make efficient use of. For example, the price of an orange will reflect a wide variety of factors – an increase in demand for orange juice in one part of the country, a smaller orange crop than usual in another part, changes in transportation costs, and so on – that no one person has knowledge of. Individual economic actors need only adjust their behavior in light of price changes (economizing, investing in an orange juice company, or whatever their particular circumstances make rational) in order to ensure that resources are used efficiently, without any central planner having to direct them.

F. A. Hayek’s classic paper “The Use of Knowledge in Society” famously argued that prices generated in a market economy function to transmit information that economic actors could not otherwise gather or make efficient use of. For example, the price of an orange will reflect a wide variety of factors – an increase in demand for orange juice in one part of the country, a smaller orange crop than usual in another part, changes in transportation costs, and so on – that no one person has knowledge of. Individual economic actors need only adjust their behavior in light of price changes (economizing, investing in an orange juice company, or whatever their particular circumstances make rational) in order to ensure that resources are used efficiently, without any central planner having to direct them. Inflation disrupts this system. As Milton and Rose Friedman summarize the problem in chapter 1of their book Free to Choose:

One of the major adverse effects of erratic inflation is the introduction of static, as it were, into the transmission of information through prices. If the price of wood goes up, for example, producers of wood cannot know whether that is because inflation is raising all prices or because wood is now in greater demand or lower supply relative to other products than it was before the price hike. The information that is important for the organization of production is primarily about relative prices – the price of one item compared with the price of another. High inflation, and particularly highly variable inflation, drowns that information in meaningless static. (pp. 17-18)

I would suggest that a similar problem is posed by what is called linguistic or semanticinflation. This occurs when the use of a word that once had a fairly narrow and precise meaning comes to be stretched well beyond that original application. The result is that the word conveys less information than it once did. One way this occurs is via the overuse of hyperbole. The author of the article just linked to gives as examples words like “awesome” and “incredible.” At one time, if an author used these terms to describe something, you could be confident that it was indeed highly unusual and impressive – a rare and extremely difficult achievement, a major catastrophe, or what have you. Now, of course, these terms have become utterly trivialized, applied to everything from some fast food someone enjoyed to a tweet one liked. At one time, calling something “awesome” or “incredible” conveyed significant information because these terms would be applied only to a small number of things or events. Today it conveys very little information because the words are applied so indiscriminately.

Now, the same thing is true of words like “racism” and “bigotry.” At one time, to call someone a “racist” implied that he was patently hostile to people of a certain race, and to call someone a “bigot” implied that he was closed-minded about certain groups of people or ideas. Accordingly, these terms conveyed significant information. If someone really was a racist, this would manifest itself in behaviors like badmouthing and avoiding people of races he disliked, favoring policies that discriminated against them, and so on. If someone really was a bigot, this would manifest itself in behaviors like being intolerant of those he disagreed with, refusing calmly to discuss or debate their ideas, and so on.

Today the use of these terms has been stretched far beyond these original applications. In part this is a result of hyperbole born of political partisanship. Labelling political opponents “racists” and “bigots” is a useful way to smear them and to stifle debate, just as hyping something as “awesome” or “incredible” is (or once was, anyway) a useful way to draw attention to it. But the stretching of these terms has also resulted from the influence of ideologies (such as Critical Race Theory) that claim to reveal novel forms of racism and bigotry of which earlier generations were unaware – forms that float entirely free of the intentions or overt behavior of individuals. The result is that even people who exhibit no behavior of the kind once thought paradigmatically racist and who harbor no negative attitudes about people of other races can still be labeled “racist” if, for example, they dissent from CRT or other woke analyses and policy recommendations.

In fact, the words have drifted so far from their original meanings that today it is precisely those who are most prone to fling around words like “racist” and “bigot” who are themselves most obviously guilty of racism and bigotry in the original, narrower and more informative senses of the terms. They will, for example, shrilly and bitterly denounce “whiteness, “white consciousness,” and the like as inherently malign, even as they claim to eschew negative characterizations of any racial group. They will refuse to engage the arguments of their opponents and try instead to shout them down and hound them out of the public square, even as they accuse those opponents of bigotry.

Partisan hyperbole and wokeness have thus introduced so much “static” (to borrow Friedman’s term) into linguistic usage that the terms no longer convey much information. They now usually tell us little more than that the speaker doesn’t like the people or ideas at which he is flinging these epithets. It is no surprise, then, that use of these terms is increasingly generating more eyeball-rolling and yawns than outrage or defensiveness. As with “awesome,” “incredible,” and the like, overuse inevitably decreases effectiveness. The indiscriminate use of “racism” and “bigotry” is like printing too much money – in the short term it produces a euphoric jolt, but in the long-term it is self-defeating.

Related posts:

June 10, 2022

The New Apologetics

I contributed an essay on “New Challenges to Natural Theology” to Matthew Nelson’s new Word on Fire anthology The New Apologetics. It’s got a large and excellent lineup of philosophers, theologians, and others. You can find the table of contents and other information about the book here.

I contributed an essay on “New Challenges to Natural Theology” to Matthew Nelson’s new Word on Fire anthology The New Apologetics. It’s got a large and excellent lineup of philosophers, theologians, and others. You can find the table of contents and other information about the book here.

June 7, 2022

COMING SOON: All One in Christ

My new book

All One in Christ: A Catholic Critique of Racism and Critical Race Theory

will be out this August from Ignatius Press. Some information about the book, including advance reviews, can be found at the Amazon link. Here’s the table of contents:

My new book

All One in Christ: A Catholic Critique of Racism and Critical Race Theory

will be out this August from Ignatius Press. Some information about the book, including advance reviews, can be found at the Amazon link. Here’s the table of contents: 1. Church Teaching against Racism

2. Late Scholastics and Early Modern Popes against Slavery

3. The Rights and Duties of Nations and Immigrants

4. What is Critical Race Theory?

5. Philosophical Problems with Critical Race Theory

6. Social Scientific Objections to Critical Race Theory

7. Catholicism versus Critical Race Theory

June 6, 2022

Anti-reductionism in Nyāya-Vaiśesika atomism

Atomism takes all material objects to be composed of basic particles that are not themselves breakable into further components. In Western philosophy, the idea goes back to the Pre-Socratics Leucippus and Democritus, and was revived in the early modern period by thinkers like Pierre Gassendi. The general spirit of atomism survived in schools of thought that abandoned the idea that there is a level of strictly unbreakable particles, such as Boyle and Locke’s corpuscularianism. Its present-day successor is physicalism, but here too there have been further modifications to the basic ancient idea. For example, non-reductive brands of physicalism allow that there are facts about at least some everyday objects that cannot be captured in a description of micro-level particles.

Atomism takes all material objects to be composed of basic particles that are not themselves breakable into further components. In Western philosophy, the idea goes back to the Pre-Socratics Leucippus and Democritus, and was revived in the early modern period by thinkers like Pierre Gassendi. The general spirit of atomism survived in schools of thought that abandoned the idea that there is a level of strictly unbreakable particles, such as Boyle and Locke’s corpuscularianism. Its present-day successor is physicalism, but here too there have been further modifications to the basic ancient idea. For example, non-reductive brands of physicalism allow that there are facts about at least some everyday objects that cannot be captured in a description of micro-level particles. Atomism has a long and interesting history in Indian philosophy as well, and an anti-reductionist version was developed within the Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika tradition (named for two systems which arose independently but later blended together). Some key arguments were worked out in response to rival, reductionist brands of atomism defended within certain schools of Buddhism. They can be found in the Nyāya-sūtra and the commentarial tradition based on it, relevant texts from which can be found in the very useful recent collection The Nyāya-sūtra: Selections with Early Commentaries, edited by Matthew Dasti and Stephen Phillips.

An important larger theme in the Nyāya-sūtra(which covers a wide variety of metaphysical topics) is the self-defeating character of skepticism. The commentators deploy this idea against Buddhist reductionist atomism as well. (Cf. pp. 100-3 of Dasti and Phillips.) Both sides make reference to ordinary objects, such as a clay pot. Both sides agree that the pot is ultimately made up of unobservable atoms. But the Buddhist reductionist says that those atoms are really allthat exist, that there is no such thing as a composite whole over and above them.

The Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika commentators argue that the position that results from this is incoherent. The Buddhist position presupposes that we can know that there are atoms, but claims that the composites we take to be made up of atoms are unreal. If they are unreal, then of course we cannot be said to know of them through perception. But the atoms are not perceptible either. So how could the Buddhist know of them any more than he knows the purportedly unreal composites? In fact it is only through the composites that we can know the atoms that make them up. Hence the composites must be real.

This argument focuses on our knowledge of objects, but a second, related point made by the commentators focuses on our active engagement with them. Composite objects can be grasped and pulled, and sometimes pulled merely by virtue of getting hold of a part of them. This could not be done if there were no composite over and above the whole. Consider how, if you spill a pile of sugar on the counter, you can’t remove it merely by grasping one side of the pile and thereby pulling the whole pile. The argument is that if the atoms were all that really existed and the composite whole did not, then you couldn’t pull on a pot (say) any more than you could pull on a pile of sugar.

The commentators consider possible objections the reductionist might raise. (Cf. pp. 103-6 of Dasti and Phillips.) Consider an object made of bits of straw, rocks, and wood glued together. You could pull on it just by virtue of pulling some part of it, but the Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika anti-reductionist would not want to consider this random object a true composite the way a pot is. The commentator Uddyotakara responds by biting the bullet and allowing that this odd object should be counted as a composite. (Here we see how Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika anti-reductionism, though something with which an Aristotelian hylemorphist is bound to sympathize, is not quite the same position. For the Aristotelian, we need to draw some important distinctions here. The random object in question would have a merely accidental form rather than a substantial form, and thus not count as a true substance, even if it is a composite of some kind.)

Another possible objection to the Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika position that the commentators consider goes like this. If you look at a forest from far enough away, it can appear to be a single, unified whole. But this is a misperception, and in fact there is nothing more there than the trees that make up the forest. Similarly, where we take there to be an everyday composite like the pot of our earlier example, there is really only the atoms that make it up.

The Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika response to this objection is that the analogy is a false one, because atoms, unlike the trees that make up a forest, are not observable. In the case of the forest, it makes sense to say that we are really perceiving trees, and simply mistaking them for some larger whole. We do, after all, really see the trees. But in the case of an object like a pot, it does not make sense to say that we are really perceiving atoms, and simply mistake them for a pot. For again, as both the Buddhist reductionist and the Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika anti-reductionist agree, we can’t perceiveatoms at all, even in a distorted way.

The commentators also consider the suggestion that the features of a composite can be accounted for entirely by way of factors like the proximity and contact between atoms, and that the “conjunction” of atoms that yields a purported composite is nothing more than that. (Cf. pp. 106-7.) The commentator Vātsyāyana responds that there has to be more to it than this insofar as “new entities” with distinctive properties can arise out of the conjunction of atoms. He seems to be presenting a variation on the theme familiar from contemporary anti-reductionist views (including contemporary hylemorphism) that wholes have causal powers and properties that are irreducible to the sum of the powers and properties of the parts. Indeed, Uddyotakara illustrates this idea by noting that “yarn is different from the cloth made from it, since the two have different causal capacities” (p. 107).

He also argues that yarn must be different from the cloth made from it insofar as the former is a cause of the latter (Ibid.). And he distinguishes this cause from the cloth’s “other causes,” such as “the weaver’s loom.” Here we might seem to have an implicit distinction between what Aristotelians call materialcause (the yarn) and efficient cause (the weaver’s loom). But Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika speaks of a thing’s “inherence cause” rather than material cause, i.e. that in which the qualities of the composite inhere. And the notion of an inherence cause is broader than that of material cause, since it can include things other than matter (e.g. a location).

Important differences aside, the Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika position, like other anti-reductionist positions in the history of philosophy, converges in key ways with Aristotelian hylemorphism. At the very least, it seems clearly to amount to a kind of non-reductive physicalism, and perhaps even approximates what is today sometimes called “structural hylemorphism” (which differs from traditional Aristotelian-Thomistic hylemorphism by taking parts to exist actually rather than virtually in wholes – thereby, from the A-T perspective, abandoning the unicity of substantial form).

As I argue in chapter 3 of Scholastic Metaphysics, these varieties of anti-reductionism are ultimately unstable attempts at a middle position between reductionism on the one hand and A-T hylemorphism on the other. Maintaining a coherent anti-reductionism requires going the whole Aristotelian hog.

Related posts:

May 31, 2022

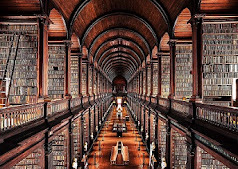

Indeterminacy and Borges’ infinite library

Jorge Luis Borges’ “The Library of Babel” (from his collection Labyrinths) famously describes an infinite library, comprising books which together represent every possible combination of characters in the alphabet in which they are written. Most of the books are gibberish, just as, if you emptied a bag of Scrabble letters onto the floor and looked at the patterns that resulted, almost none of what you’d see would count as a genuine word or sentence. But because every possible combination is there, many intelligible books are there too. In fact, every possible such book is there, so that the library contains all knowledge, every truth there is about everything. For any of these truths, though, the trick is to find it somewhere in this infinite, bewildering Babel.

Jorge Luis Borges’ “The Library of Babel” (from his collection Labyrinths) famously describes an infinite library, comprising books which together represent every possible combination of characters in the alphabet in which they are written. Most of the books are gibberish, just as, if you emptied a bag of Scrabble letters onto the floor and looked at the patterns that resulted, almost none of what you’d see would count as a genuine word or sentence. But because every possible combination is there, many intelligible books are there too. In fact, every possible such book is there, so that the library contains all knowledge, every truth there is about everything. For any of these truths, though, the trick is to find it somewhere in this infinite, bewildering Babel. That’s the idea, anyway, and Borges’ narrator’s description of the library, its history, and its denizens is arresting. But would such a library really contain all knowledge? Yes and no. Unusual as the library is, it is nevertheless made up of books, more or less as we know them – that is to say, physical objects with marks whose semantic meaning is a matter of linguistic convention. And as I have discussed many times over the years in various books, articles, and here at the blog, systems of material representations (words, pictures, or what have you) are, considered just by themselves, inherently indeterminate, inexact, or ambiguous in their content. Given their physical properties alone, there is no fact of the matter about exactly what meaning they convey.

The indeterminacy of the physical

This is a truth acknowledged by philosophers of widely divergent commitments, from W. V. Quine to James F. Ross, and the conclusions they draw from it are no less divergent. I follow Ross in holding that, since we have thoughts which dohave determinate, exact, or unambiguous content, the lesson we should draw is that thought cannot be identified with any system of material representations. For example, it cannot be identified with representations encoded in brain activity, in the electrical circuitry of a computer, or the like. (I develop this line of argument in detail in my ACPQ article “Kripke, Ross, and the Immaterial Aspects of Thought” and have defended it against various objections here at the blog, for example in this post.)

Quine’s famous example involves a linguist trying to interpret a native speaker’s utterance of “Gavagai” in the presence of a rabbit, where the utterance is in some heretofore unknown language. The linguist could translate it as “Lo, a rabbit!”, but might also produce translations that, instead of making reference to a rabbit, referred instead to either a temporal stage of a rabbit or an undetached rabbit part. Which translation is to be preferred would depend on what beliefs the linguist thought he should attribute to the native speaker. Does the speaker and the community he comes from fundamentally conceive of the world in terms of persisting substances? In that case, the first translation would be preferable. Or do they conceive of it instead in terms of ephemeral events? In that case, the translation that made reference to a “temporal stage of a rabbit,” however odd to our ears, would be the one to go with. And so on.

Deciding between the options would require appeal to other utterances of the speaker, along with the speaker’s behavior in general and the physical surroundings in which the conversation takes place. But these other utterances, and the behavior as well, are also all susceptible of various alternative interpretations. Suppose that the linguist is able to put together three different manuals of translation of the native speaker’s language, all of which are equally useful in allowing him to communicate with the speaker, but none of which is consistent with the others (since, for example, they translate “gavagai” in the three different ways described). Then, Quine says, if behavior, facts about physical surroundings, and the like are all we have to go on, then there just is no fact of the matterabout what the speaker really means. The choice of which translation manual to use is a pragmatic matter.

Since Quine thinks that is all we have to go on, he draws the radical conclusion that there is indeed no fact of the matter about what the speaker means. And since the scenario he describes differs only in degree from the situation we’re all in with respect to each other, he concludes that there is no fact of the matter about what any of us means either. Other philosophers, judging (quite rightly in my view) that this position is incoherent, conclude instead that behavior, physical surroundings, and the like are not all that we have to go on.

Now, it turns out that if the rest of what we have to go on is just more in the way of physical facts, then that will not suffice to change the outcome of Quine’s argument in the least. For example, as Saul Kripke showed, appealing to computer programs purportedly being implemented in the brain makes no difference at all, because exactly which program any machine (or the brain) is running is itself indeterminate from the physical facts alone. Thus does Ross conclude that the semantic content of our utterances, and the conceptual content of our thoughts (which is the source of the content of our utterances) is not to be identified with any physical or material properties at all. (Again, see the articles linked to above for detailed exposition of the argument, responses to various objections, and so on.)

Infinite, schminfinite

Note that adding material representations (words, computer code, whatever) to a system of representations ad infinitum doesn’t change things in the least. Even an actually infinite series of material representations will, considered just by itself, be as indeterminate or ambiguous in its semantic content as a finite series. To see this, consider the following series:

…-4, -3, -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4 …

Suppose that in some infinite corridor of Borges’ library, you can find this series written on a wall, extending forever in both directions. Wouldn’t that unambiguously represent the series of integers? Given our conventions, sure it would. But given onlythe physical properties of the representations, it would not. For the physical properties do not themselves have any inherent connection to the numbers represented. There is, for example, no inherent connection between “4” and the number 4, any more than there is an inherent connection between “IV” and the number 4 or between “IIII” and the number 4. That they are related is merely a matter of our conventions. Suppose that “4” instead stood for cheeseburger, that “7” stood for carburetor, that “18” stood for collapse of the wave function, that “47” stood for Stan Lee’s sunglasses, and so on. Then the infinite series written on the corridor walls would not represent the integers, but rather some bizarre sequence of disconnected concepts.

This is in fact why most of the books in Borges’ library would be gibberish. Linguistic representation involves layers of conventions. For example, there is in English the convention by which “a,” “b,” “c,” etc. count as letters. But there is the further convention by which the sequences of letters “dog” and “cat” count as words. There is, by contrast, no convention by which “rbxzt” or “ZZggTT” counts as a word. So, putting limits on what counts as a letter only goes so far in excluding meaningless marks. In English, the conventions will allow in “a,” “b,” “c,” etc. but not, say, “ȸ” or “Ж.” But “a,” “b,” “c,” etc. will still yield meaningless combinations of marks. Languages are in this way inefficient, allowing for the possibility of enormous amounts of nonsense unless some special conventions exclude it, but where (given the indeterminacy of the physical) there is no way to exclude all of it.

Could there be a system of representations that contains no gibberish? And, for that matter, no indeterminacy of meaning? Yes, but it would have to comprise what the Scholastic philosopher John Poinsot (also known as John of St. Thomas) called “formal signs,” which are signs that are nothing but signs. To explain the idea by way of contrast, consider again the written word “dog.” This is a sign that is more than a sign. It is, in particular, a sequence of physical shapes and on top of that it is a representation of dogs. A formal sign that represented dogs would be one that has no such double nature. It would be a representation of dogs and nothing more than that – it would not, for example, also be a sequence of shapes, or of noises, or the like. Concepts, according to Scholastics like Poinsot, are formal signs in this sense. (For a bit more on this notion, see pp. 27-28 of “Kripke, Ross, and the Immaterial Aspects of Thought,” linked to above.)

But a system of signs that are nothing but signs would not be a system of material representations. For to be a material representation just is to have some additional nature over and above being a representation (for example, the nature of having such-and-such a shape, such-and-such a chemical composition, or what have you). So, if there could be a system of representations that contained no gibberish, and also no indeterminacy or ambiguity of content, then that too would not be a system of material representations. It is because material representations have this dual nature – of being representations and also, on top of that, material things of a certain kind – that material properties and meaning can “come apart” from one another in a way that entails either gibberish or ambiguity.

Hence, a system of representations containing no gibberish or indeterminacy of meaning would not be Borges’ library which, qua library, comprises material representations (books, written words, etc.). Borges’ library could contain all possible knowledge only if there is something distinct from the library, by reference to which (some of) the linguistic marks contained in the books by convention count as representations of all possible knowledge. Borges’ narrator recognizes that the library by itself does not suffice to determine exactly what any book within it represents, saying:

An n number of possible languages use the same vocabulary; in some of them, the symbol library allows the correct definition a ubiquitous and lasting system of hexagonal galleries, but library is bread or pyramid or anything else, and these seven words which define it have another value. You who read me, are You sure of understanding my language? (p. 85 of the Penguin books edition)

Beyond the library

Of course, the denizens of Borges’ library, who read and interpret the books, are distinct from the library itself, and they assign meanings to the linguistic representations contained therein. But they are not the ultimate source of the information said to be contained in the library, and could not be, since in none of their minds (considered either individually or collectively) is all of that information to be found. That’s precisely why Borges describes some of them as searching the library for books that would contain certain secrets they would like to know. In some way, then, there must be something distinct not only from the library, but also from the minds of its inhabitants, that determines the meaning of the (subset of) representations contained in the books that count as all possible knowledge. What would this be?

One possible answer is implied by mathematician and science fiction writer Rudy Rucker’s notion of the “Mindscape,” which I discussed in a post some years back. The Mindscape is essentially the collection of all the possible concepts, propositions, and inferences that a mind might entertain, considered as something analogous to Plato’s realm of the Forms. But as the Neo-Platonic/Augustinian tradition argued – and as I argue too, in chapter 3 of Five Proofs of the Existence of God – ultimately we can make sense of the Platonic realm only if we understand it as comprising ideas in the divine intellect. (Though as I explain in the post just linked to, Rucker’s Mindscape is not itself to be identified with the divine intellect, but rather as something that ultimately presupposes the divine intellect.)

Though Borges’ infinite library does not exist, something analogous to it – in particular, analogous to it in its being a repository of all knowledge – could exist, and indeed does exist, viz. the divine intellect. But there is in it neither gibberish nor indeterminacy.

Related reading:

Kripke, Ross, and the Immaterial Aspects of Thought

Revisiting Ross on the immateriality of thought

Kripke contra computationalism

May 23, 2022

The hollow universe of modern physics

To say that the material world alone exists is not terribly informative unless we have some account of what matter is. Those who are most tempted to materialism are also inclined to answer that matter is whatever physics says it is. The trouble with that is that physics tells us less than meets the eye about the nature of matter. As Poincaré, Duhem, Russell, Eddington, and other late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century philosophers and scientists were keen to emphasize, what physics gives us is the abstract mathematical structure of the material world, but not the entire nature of the concrete entities that have that structure. It no more captures all of physical reality than a blueprint captures everything there is to a house. This is, of course, a drum I’ve long banged on (for example, in

Aristotle’s Revenge

).

To say that the material world alone exists is not terribly informative unless we have some account of what matter is. Those who are most tempted to materialism are also inclined to answer that matter is whatever physics says it is. The trouble with that is that physics tells us less than meets the eye about the nature of matter. As Poincaré, Duhem, Russell, Eddington, and other late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century philosophers and scientists were keen to emphasize, what physics gives us is the abstract mathematical structure of the material world, but not the entire nature of the concrete entities that have that structure. It no more captures all of physical reality than a blueprint captures everything there is to a house. This is, of course, a drum I’ve long banged on (for example, in

Aristotle’s Revenge

). The methods of physics as they’ve been understood since the time of Galileo make this limitation inevitable. As philosopher of physics Roberto Torretti writes:

While Aristotelian science favored loving attention to detail, through which alone one could succeed in conceiving the real in its full concreteness, Galileo and his followers conducted their research with scissors and blinkers… The natural processes and states of affairs under study were represented by simplified models, manageable instances of definite mathematical structures. The inevitable discrepancies between the predicted behavior of such models and the observed behavior of the objects they stood for were ascribed to “perturbations” and observation errors. (The Philosophy of Physics, pp. 431-32)

The “scissors and blinkers” have to do with the way that Galileo and his successors ignored or cut away from their representation of the physical world anything that cannot be captured mathematically – secondary qualities (colors, sounds, etc.), teleology or final causes, moral and aesthetic value, and so on. Thus, as Torretti writes, “modern mathematical physics began in open defiance of common sense” (p. 398). Galileo expressed admiration for those who, applying this method in astronomy, had “through sheer force of intellect done such violence to their own senses as to prefer what reason told them over that which sensible experience plainly showed them to the contrary” (quoted at p. 398).

The point isn’t that this is necessarily bad. On the contrary, it made it possible for physics to become an exact science. But physics did so precisely by deliberately confining its attention to those aspects of nature susceptible of an exact mathematical treatment. This is like a student who ensures that he’ll get A’s in all his classes simply by avoiding any class he knows he’s not likely to get an A in. There may be perfectly good reasons for doing this. But it would be fallacious for such a student to conclude from his GPA that the classes he took taught him everything there is to know about the world, or everything worth knowing, so that the classes he avoided were without value. And it is no less fallacious to infer from the success of physics that there is nothing more to material reality, or at least nothing more worth knowing, than what physics has to say about it (even if a lot of people who like to think of themselves as pretty smart are guilty of this fallacy).

Moreover, to take modern physics’ mathematical description of matter to be an exhaustive description would, as it happens, more plausibly underminematerialism altogether rather than give content to it. In particular, it arguably leads to idealism. I briefly noted in Aristotle’s Revenge (at pp. 176-77) how twentieth-century physicists Eddington and James Jeans drew this conclusion. Torretti (at pp. 98-104) notes that Leibniz and Berkeley did the same.

Here’s one way to understand Leibniz’s argument (which Torretti finds in some of Leibniz’s letters). Every geometry student knows that perfect lines, perfect circles, and the like cannot be found in the world of everyday experience. Concrete empirical geometrical properties are at best mere approximations to the idealizations that exist only in thought. But the mathematical description of the material world afforded by physics is also an abstract idealization. As such, it too can exist only in thought, and not in mind-independent reality. Of course, Leibniz’s theory of monads already purports to establish that there is no mind-independent reality, so that perception no more gives us access to such a reality than physics does. The point of the argument of the letters (as I am interpreting it) is to note that the abstractions of physics cannot be said to give us a betterfoundation for conceiving of the physical world as mind-independent. On the contrary, qua abstractions they are even less promising candidates for mind-independence than the ordinary perceptual world is.

Berkeley adds the consideration that systems of signs, such as the mathematics in which modern physical theory is expressed, can be useful in calculations even though some of the signs do not correspond to anything. As it happens, I discussed this theme from Berkeley in an earlier post. The utility of a system of signs in part derives from the conventions and rules of the system, rather than from any correspondence to the reality represented by the system. This conventional element in physics’ mathematical representation of the material world reinforces, for Berkeley, that representation’s mind-dependence.

To try to give content to materialism by identifying matterwith whatever physics says about matterwould, if this is right, essentially be to transform materialism into idealism – that is to say, to give up materialism for its ancient rival. To avoid this, the materialist could, of course, appeal to some philosophical theory about the nature of matter that recognized that physics tells us only part of the story. But this would be to acknowledge that materialism is, after all, itself really just one philosophical theory among others, no better supported by science than its rivals are. It would be to see through the illusion that metaphysical conclusions can be read off from the findings of modern science.

The picture of nature provided by modern physics is in fact highly indeterminate between different possible metaphysical interpretations – materialist, idealist, dualist, panpsychist, or (the correct interpretation, in my view) Aristotelian. It is (to borrow from Charles De Koninck) a hollow vessel into which metaphysical water, wine, or for that matter gasoline might be poured. But it doesn’t by itself tell us which of these to pour.

Again, see Aristotle’s Revenge for more, or, for instant gratification, the posts linked to below.

Related posts:

Meta-abstraction in the physical and social sciences

The particle collection that fancied itself a physicist

May 14, 2022

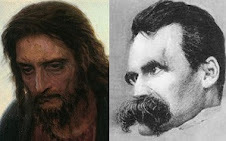

Nietzsche and Christ on suffering

Over and over we are taught in scripture and tradition that suffering is the lot not only of mankind in general, but of the Christian in particular. Christ, the “man of sorrows and acquainted with grief” (Isaiah 53:3), is our model. When he warned that he must suffer and die, “Peter took him and began to rebuke him, saying, ‘God forbid, Lord! This shall never happen to you,’” which prompted Christ’s own famous rebuke in response:

Over and over we are taught in scripture and tradition that suffering is the lot not only of mankind in general, but of the Christian in particular. Christ, the “man of sorrows and acquainted with grief” (Isaiah 53:3), is our model. When he warned that he must suffer and die, “Peter took him and began to rebuke him, saying, ‘God forbid, Lord! This shall never happen to you,’” which prompted Christ’s own famous rebuke in response: But he turned and said to Peter, “Get behind me, Satan! You are a hindrance to me; for you are not on the side of God, but of men.” Then Jesus told his disciples, “If any man would come after me, let him deny himself and take up his cross and follow me. For whoever would save his life will lose it, and whoever loses his life for my sake will find it. (Matthew 16:22-25)

St. Paul tells us that he repeatedly begged God to relieve him of some persistent source of torment:

But he said to me, “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness”… For the sake of Christ, then, I am content with weaknesses, insults, hardships, persecutions, and calamities; for when I am weak, then I am strong. (2 Corinthians 12: 9-10)

The lives not only of the martyrs, but of the saints more generally from the time of the early Church to the present, witness to suffering’s being the norm in the Christian life. Pope St. John Paul II even spoke of a “Gospel of suffering” (a phrase also used by Kierkegaard), the message of which is that suffering redeems us and makes possible a particularly intimate union with Christ.

Take up your cross

In the Christian understanding, then, suffering is, to borrow the software programmer’s phrase, a feature, not a bug. It is not an inexplicable fact about the human condition, nor an embarrassment to Christian theology that the tradition would prefer to distract us from. On the contrary, the tradition puts the reality of suffering front and center, and insists that it is an inevitable consequence of original and actual sin. In an earlier post, I developed this theme, and argued that modern bafflement at the suffering that exists in the world is more a consequence of apostasy from Christianity than a cause of it. It is largely an artifact of the softness and decadence of modern Western affluence.

That contemporary Christians have themselves been corrupted by this softness and decadence is evident from the way they deal with resistance to the Church’s hard teachings, especially on matters of sex. They are keen to reassure our sex-obsessed society that sexual sins are not the worst sins. This is like reassuring Bernie Madoff that fraud is not the worst of sins, or Watergate conspirators that perjury is not the worst of sins – it is true, but not exactly where the emphasis needs to be. Sexual sins, while not the most serious, are still serious, for they are uniquely destructive of rationalityand social order. They are also very easy to fall into and can be very difficult to get out of, and as a result are extremely common (much more so than fraud and perjury, for example). Their prevalence and intractability, and the widespread irrationality and social disorder that are their sequel, are on vivid display all around us. Yet even most conservative churchmen and theologians would prefer to talk about almost anything else. Why?

Naturally, cowardice is a factor. But it is not just a matter of failing to do one’s duty on this or that particular uncomfortable occasion. It is, I would argue, a more general unwillingness to face up to the unavoidability of suffering, or to require others to face up to it. The litany of complaints about Christian sexual morality is familiar: But I’m in an unhappy marriage. But I’m in love with someone else. But it’s a habit I can’t break. But I can’t help feeling this attraction. But I was born this way. But I’m frustrated and can’t find anyone to marry. But I feel like I’m in the wrong body. But I can’t handle a baby right now. But, but, but. You mean I cannot fulfill my desires? You mean I have to suffer with these feelings, possibly for the rest of my life?

The traditional Christian answer would be: “Yes, that’s exactly right. Take up your cross.” But the modern Christian gets weak in the knees, changes the subject, and perhaps even feels guilty for having raised it in the first place.

Note that I am not saying that “Take up your cross” is all that need be said. By no means should that be the last word. But it must be the first word. Modern Christians suppose otherwise because they confuse mercy with feeling sorry for someone. These are not the same thing. More precisely, though mercy typically does involve feeling sorry for someone, not everything that is done out of feeling sorry for someone amounts to mercy.

The quality of mercy

Mercy, as Aquinas teaches in Summa Theologiae II-II.30.3, is a virtue. Now, a virtue is a mean between extremes, falling between a vice of excess and a vice of deficiency. The vice of deficiency in this case would, of course, be mercilessness. What would be the vice of excess where mercy is concerned?

Aquinas notes that “mercy signifies grief for another's distress. Now, this grief may denote, in one way, a movement of the sensitive appetite, in which case mercy is not a virtue but a passion.” What he means is that sometimes what we have in mind when we speak of “mercy” is a kind of passion or feeling, namely a feeling of grief over the distress another person is experiencing. This feeling is not itself the virtue of mercy. Rather, it is typically associated with the virtue. (Many feelings are like this. For example, love is typically associated with feelings, but it is not itself a feeling. Rather, it is the willing of what is good for someone. That can exist even when the feelings are absent, and the feelings can exist when genuine love is absent. There is a rough-and-ready correlation between a given virtue and certain feelings, but they must not be confused.)

When the feelings in question are governed by reason, then we have genuine mercy. But Aquinas distinguishes genuine mercy from “the mercy which is a passion unregulated by reason: for thus it impedes the counselling of reason, by making it wander from justice” (emphasis added). An example would be feeling so sorry for Bernie Madoff that one advocates letting him off scot-free, even if he is unrepentant.

This would be what we might call a vice of sentimentality, which involves putting feelings in the driver’s seat where reason should be. To be sure, because we are rational animals rather than angelic intellects, we needfeelings to give us rough-and-ready everyday guidance. When all goes well, they prompt us to do the right thing when reason is weak, or when there is no time to think through a problem. Still, they are only ever a highly fallible assistant to reason, and, like all things human, can become distorted. This is what happens when the feelings associated with mercy for a sinner become so strong that they lead us to ignore the fact that he is a sinner. To be sure, genuine mercy does more than merely call for repentance and penance. But it does not do less than that. And it helps the sinner (as gently as possible) to accept the inevitability of the suffering that results, rather than pretending that it is avoidable, or simply changing the subject.

From Christ to antichrist and back again

That the acceptance of suffering is necessary to perfecting us is basic Christian moral wisdom, but at least to some extent it is even part of the natural law. That is clear from the example of someone who in other respects couldn’t be further from the Christian view of things, namely Friedrich Nietzsche.

Like Aquinas, Nietzsche distinguishes between two kinds of pity, and favors one while rejecting the other. There is, Nietzsche says, a kind of pity which sees man in his lowly condition and seeks to ennoble him. But there is another kind of pity which makes man smaller, and is born of sympathy with “those addicted to vice” and with the “grumbling” and “rebellious” elements of society more generally (Beyond Good and Evil 225, Kaufmann translation). Under the influence of this false pity, Nietzsche says:

Everything that elevates an individual above the herd and intimidates the neighbor is henceforth called evil; and… the mediocrity of desires attains moral designations and honors. Eventually, under very peaceful conditions, the opportunity and necessity for educating one’s feelings to severity and hardness is lacking more and more; and every severity, even in justice, begins to disturb the conscience. (201)

The inevitable result, Nietzsche argues, is collapse into a general licentiousness:

There is a point in the history of society when it becomes so pathologically soft and tender that among other things it sides even with those who harm it, criminals, and does this quite seriously and honestly. Punishing somehow seems unfair to it, and it is certain that imagining “punishment” and “being supposed to punish” hurts it, arouses fear in it. “Is it not enough to render him undangerous? Why still punish? Punishing itself is terrible.” With this question, herd morality, the morality of timidity, draws its ultimate consequence. (201)

The hard truth, Nietzsche teaches, is that to achieve what is truly good for individuals and society requires the discipline of suffering, and that those who blind themselves to this are not the friends of mankind, but its enemies:

You want, if possible – and there is no more insane “if possible” – to abolish suffering. And we? It really seems that we would rather have it higher and worse than ever. Well-being as you understand it – that is no goal, that seems to us an end, a state that soon makes man ridiculous and contemptible – that makes his destruction desirable.

The discipline of suffering, of great suffering – do you not know that only this discipline has created all enhancements of man so far? (225)

Similarly, in The Will to Power, he writes:

To those human beings who are of any concern to me I wish suffering, desolation, sickness, ill-treatment, indignities – I wish that they should not remain unfamiliar with profound self-contempt, the torture of self-mistrust, the wretchedness of the vanquished: I have no pity for them, because I wish them the only thing that can prove today whether one is worth anything or not – that one endures. (910, Kaufmann and Hollingdale translation)

It is ironic that a man who characterized himself as an “antichrist” should ape Christ’s call to take up the cross. But it is not entirely surprising, for the enemies of the Faith typically mimic it in some respects, even as they reject it. And Nietzsche’s embrace of suffering is certainly not identical with that of the Christian. Nietzsche is an elitist who neither calls all men to excellence nor thinks all capable of it; Christ teaches that all are made in God’s image, calls all to repentance and holiness, and sacrifices his life for all (even if not all will accept this sacrifice). For the strength needed to bear up under suffering, Nietzsche would look within; the Christian knows that it is possible only through grace. The Nietzschean superman glorifies himself; the Christian glorifies God.

But if Christians can love their enemies, they can learn from them too. It is a sign of the diabolical disorder of our times that they need from one of their greatest enemies a reminder of the difference between true and false mercy, and of the suffering entailed by the former.

Related posts:

The “first world problem” of evil

May 9, 2022

End of semester open thread

Let’s start the summer break off right, with an open thread. Now’s the time to get that otherwise off-topic obsession of yours off your chest, at long last. From plunging stocks to Pet Rocks, from buying Twitter to Gary Glitter to sharing an Uber with Martin Buber, everything is on topic. The usual rules of good taste and discretion apply. Previous open threads archived here.

Let’s start the summer break off right, with an open thread. Now’s the time to get that otherwise off-topic obsession of yours off your chest, at long last. From plunging stocks to Pet Rocks, from buying Twitter to Gary Glitter to sharing an Uber with Martin Buber, everything is on topic. The usual rules of good taste and discretion apply. Previous open threads archived here.

May 5, 2022

Benedict is not the pope: A reply to some critics

Patrick Coffin has posted an open letter by Italian writer Andrea Cionci, replying to my recent article criticizing Benevacantism. What follows is a response. In his introduction to the letter, Patrick objects to my use of the label “Benevacantism,” calling it a “nonsensical devil term”(!) I can understand why he doesn’t like the word, because it is an odd one and doesn’t really make much sense. But I didn’t come up with it. I had to use some label to refer to the view, and chose “Benevacantism” simply because it seemed to be the one most widely used. But Patrick prefers the label “Benedict is Pope” or “BiP” for short, so in what follows I’ll go along with that.

Patrick Coffin has posted an open letter by Italian writer Andrea Cionci, replying to my recent article criticizing Benevacantism. What follows is a response. In his introduction to the letter, Patrick objects to my use of the label “Benevacantism,” calling it a “nonsensical devil term”(!) I can understand why he doesn’t like the word, because it is an odd one and doesn’t really make much sense. But I didn’t come up with it. I had to use some label to refer to the view, and chose “Benevacantism” simply because it seemed to be the one most widely used. But Patrick prefers the label “Benedict is Pope” or “BiP” for short, so in what follows I’ll go along with that. In addition, Patrick says: “Feser also tweeted a seven-point criticism of my evidence VIDEOthat Pope Benedict XVI is still the true Pontiff of the Catholic Church. Which I answered, point by point.” I don’t know why Patrick would make such a bizarre claim, but whatever the reason, it isn’t true. I have written nothing, on Twitter or anywhere else, about his video. All I did on Twitter was object to his false and gratuitous accusation that Catholic World Report and I were acting out of a financial motivation. And since I never wrote any “seven-point criticism” of his video, Patrick naturally could not have written a “point by point” response to it. Perhaps he has me confused with someone else?

The “emeritus” red herring

Anyway, let’s move on to Cionci’s reply. He opens with what he presents as merely a secondary argument in favor of the BiP position, even acknowledging that it is “very trivial.” That’s a good thing, because the argument is extremely weak indeed, even if some BiP advocates (like Patrick in his video) try to make hay out of it. Cionci writes:

If Pope Benedict had really wanted to abdicate, as the official narrative would [sic] – given the discretion, modesty, and correctness of the man – he certainly would not have made all those messes: to remain with the pontifical name, dressed in white, in the Vatican, under a canonically non-existent papacy emeritus. What good is it? Out of vanity? For the sake of throwing a billion or more faithful into confusion?

End quote. To see what is wrong with this, consider that if I were to retire and then take the title “Professor Emeritus,” no one would think: “Gee, this is confusing! Is he really retiring or not?” And they would not think this even if I asked people to continue calling me “Professor Feser,” wore a tweed jacket, kept hanging around campus, kept writing books, etc. A “Professor Emeritus” is not some unusual kind of professor, but rather a former professor. The title is honorific and implies no continuing status as a faculty member. Everyone knows this, of course.

But the same thing is true of the title “Pope Emeritus.” A “Pope Emeritus” is not an unusual kind of pope, but rather a kind of former pope. That’s all. And the continued use of the papal name, the white garments, living in the Vatican, etc. are analogous to a former professor’s still being called “Professor,” still coming to campus from time to time, etc.

Hence the facts cited by Cionci and other BiP advocates are no evidence at all for the BiP thesis, not even “very trivial” evidence. Indeed, they constitute powerful evidence against the thesis. If you were wondering whether someone was still a professor, and then you heard that he has taken the title “Professor Emeritus,” you would hardly conclude from that that he is still a professor. On the contrary, you would conclude that he must notbe. Why would he call himself “Emeritus” if he was? In the same way, the fact that Benedict calls himself “Pope Emeritus” is, all by itself, compelling evidence that he is not the pope, and that he “really wanted to abdicate,” to use Cionci’s words. Cionci speaks of the “confusion” that the “Pope Emeritus” title and other papal trappings have caused, but the only confusion here is on the side of the BiP advocates. Everyone else realizes that “Benedict is Pope Emeritus” logically entails “Benedict is not the pope.”

Much ado about “munus”

Cionci’s main argument, though, is the business about the purportedly momentous distinction between “munus” and “ministerium” that BiP advocates are always on about, as I noted in my previous article. To be sure, he appeals to more than just this distinction. Indeed, there is much (frankly bizarre) heavy going about the allegedly grave significance of the precise moment of Benedict’s post-resignation helicopter ride, of the “ancient papal time system” (whatever that is), of “German dynastic law,” of the “German Carnival Monday” celebration, of St. Malachi’s prophecy, of whether the phrase “Supreme Pontiff” is written in caps, and other esoterica and minutiae. And we are told that we must discern, between the lines of official statements, what Benedict is subtly trying to convey to us through a “communicative system” that Cionci calls the “Ratzinger Code.” All of this has been pieced together by Cionci by collating “the contribution of numerous specialists: theologians, Latinists, canonists, psychologists, linguists, historians etc.”

Hence, despite Cionci’s insistence that Benedict would never want to cause “messes” or “confusion,” he still somehow concludes that the Pope Emeritus signals his true meaning to the faithful only through the painstaking efforts, over many years, of a diverse group of independently operating scholars, as assembled by and filtered through Italian writers who get Patrick Coffin to post their stuff on his website.

Because I don’t want to be uncharitable, I don’t want to call all of this nuts. But I do want to make it clear that that is absolutely the only reason I do not want to call it that.

In any event, it is still the munus/ministerium distinction that is doing the heavy lifting, so (mercifully) we can just focus on that and leave “Ratzinger Code” adepts to their labors. Here it is useful to bring to bear a recent exchange at Matt Briggs’ website between Fr. John Rickert, a critic of the BiP theory, and historian Edmund Mazza, a prominent defender of the theory. It must be said at the outset, in fairness to Prof. Mazza, that he is a much more sober-minded advocate of the view than the folks I’ve been talking about so far in this post. All the same, Fr. Rickert decisively refutes Mazza’s position, and in particular the arguments based on the munus/ministerium distinction.

Recall that the distinction is that between the officeof the papacy (which is what “munus”is said to connote) and the active exercise of the powers of the office (which is what “ministerium” is said to convey). BiP theorists like Mazza try to make a big deal out of the fact that in the declaration of his resignation, Benedict referred at first to the “munus” of the papacy, but then goes on to say that he is renouncing the “ministerio” of the bishop of Rome. What this means, they claim, is that he gave up only the active exercise of the office of the papacy, but not the office itself.

To see what is wrong with this, imagine that Joe Biden read a statement wherein he first referred to the “presidency” and then a little later on said he was resigning as “chief executive” of the government of the United States. Would you think: “Hmm, it seems that he might be giving up only the active exerciseof the presidency, but not the presidency itself!” Would we be faced with the puzzle of whether it is still really Biden rather than Kamala Harris who is now president? Of course not, because everyone knows that to speak of the “presidency” and to talk about being “chief executive” of the U.S. government are two ways of saying the same thing. There would be absolutely no significance to the use of different terms at the beginning of the statement and the end of it.

But the same thing is true of Benedict’s statement. For as Fr. Rickert emphasizes, “munus” and “ministerium” too can mean the same thing. Indeed, Mazza and Cionci themselves admit that it can mean the same thing. They admit that it is only context, and not the words considered in isolation, that can tell us whether the speaker means to use them in different senses. So what is the relevant context in this case?

Mazza answers by trying to tease out significance from something Benedict said in an interview years after resigning, and something else he said in a book years before becoming pope. Cionci answers by appealing to the “Ratzinger Code” exotica referred to above. What they ignore is what most readers might naturally suppose to be the most important bit of context – namely, what else he said in the course of declaring his resignation.

Fr. Rickert, however, does not ignore this. He notes that Benedict stated at the time that “the See of St. Peter will be vacant… and a Conclave for electing a new Pope…must be called.” That shows that he believed himself to be renouncing precisely the office of the papacy itself, and not merely its active exercise. In reply to Mazza, Fr. Rickert also points out that in the very title of his declaration of his resignation, Benedict speaks of the munus in the genitive singular, and of its “abdication,” or disowning of the office in an unequivocal sense. Mazza himself quotes Benedict’s statement that he has given up “the power of the office for the government of the Church.” And as Fr. Rickert notes, in canon law the office of the papacy and the right to exercise its powers go hand in hand. To give up the latter entails giving up the former.

Hence the immediate context of Benedict’s use of “munus” and “ministerium” makes it crystal clear that he meant to use them as synonyms. Nor, of course, did he say anything whatsoever at the time to indicate otherwise. It is only later on that people started trying to tease out some remarkable, hidden significance to the use of the two terms.

I think it is worth adding that, as anyone who has read his work knows, Benedict does not write like a Thomisic philosopher or canon lawyer, but has a more literary style. Hence, where a dry, plodding Scholastic (like me) might just repeat “pope” or “papacy” several times in a single paragraph, Benedict prefers to mix it up with more colorful phrases like “Petrine ministry.” It is fallacious to infer some hidden meaning lurking behind what are really nothing more than stylistic flourishes.

The (unmeetable) burden of proof

Amazingly, in what purports to be a reply to my article, neither Cionci nor Patrick say a single thing in response to the arguments I gave there! In particular, they have nothing to say about what I argued are the theologically catastrophic implications of the BiP position, which are far worse than the problems with Francis’s pontificate (which BiP advocates delude themselves into thinking they are solving by claiming Francis to be an antipope). They simply rehash standard BiP talking points (and, in Patrick’s case, he repeats the third-rate debater’s trick of insinuating that I have some financial motivation).

This illustrates the unseriousness of much BiP argumentation. But the unseriousness is not merely intellectual. It is moral. For a Catholic publicly to accuse a sitting pope of being an antipope is not merely to entertain some eccentric theological opinion. It is (if the accusation is false) potentially to lead fellow Catholics into the grave sin of schism. Moreover, the very foundations of the day-to-day governance of the Church – the binding force of papal directives, the validity of ordinations (and thus of the sacraments), and so on – depend on knowing who the pope really is. The BiP thesis calls all of that into question. Canon law famously declares that marriages are presumed valid unless proved invalid. This makes sense given how much in the lives of men, women, and children rides on being able to know that one is validly married. How much more must a papal resignation be presumed valid, when the basic governance of the entire Church rides on it?

Nor, if such a resignation were invalid, do laymen have any business proclaiming it such – say, by confidently declaring from their Twitter accounts that we have a “fake pope,” on the grounds that some academic one has interviewed for one’s podcast has said so. Even if there were a serious case for the BiP position (which, as we have seen, there is not), it is for the Church alone to decide the matter.

But even this is merely academic. For it’s not just that the burden of proof is on BiP advocates, and not on their critics. It’s not just that it is for the Church, and not for BiP advocates, to settle the question. An even more fundamental problem for the BiP position is that the matter has already been settled. The relevant jury is not still out on this. It came in with its verdict years ago. The matter was settled when Francis was elected and the Church (including Francis’s predecessor Benedict himself, and including Catholics who were not happy with the results) accepted that he was pope.

Now, as I and others have shown, the arguments claiming to establish the invalidity of Benedict’s resignation are no good. And as canon lawyers like Ed Peters have shown, the arguments claiming to establish that Francis’s election was invalid are also no good. But these are not the considerations I primarily have in mind here. For even apart from the specifics of those debates, and a priori, we can know from the very nature of the papal office that the BiP position is simply a non-starter. The reason is that, for the Church as a whole corporate body to accept as pope a man who is not in fact the pope would be contrary to her indefectibility, and thus contrary to Christ’s promise that the gates of Hell will not prevail against her. This is just standard, traditional Catholic theology. (Robert Siscoe provides a useful overview of the main points here and here.) Hence the morally unanimous acceptance of Francis as pope in the years immediately following his election is by itself enough to ensure that he really is pope.

As Aquinas observes, though schism is distinct from heresy, they are closely related. Quoting St. Jerome, he notes that “there is no schism that does not devise some heresy for itself, that it may appear to have had a reason for separating from the Church.” In the present case, though denying that Francis is pope is not itself heretical, it does presuppose the doctrinally erroneous proposition that the Church can err even when morally unanimous in accepting a man as pope.

Hence, though some of them mean well and are understandably anxious about the state of the Church, those peddling the BiP position are on extremelydangerous ground, doctrinally and spiritually. It is not only a gigantic time-waster (which would be bad enough when the Church and the world are faced with serious problems as it is), but something much worse.

April 30, 2022

Socratic loyalty

Socrates was so critical of his country that he was put to death by it. Yet he could have escaped execution had he wanted to. The reason he did not, as he famously explained in Plato’s

Crito

, was out of loyalty to the country of which he was so critical, and which willed to destroy him. I don’t think that Socrates’ example is, in this case, one that we are bound to follow; Aristotle did no wrong in fleeing, lest Athens sin twice against philosophy. All the same, that example is worth pondering for contemporary conservatives tempted to oikophobia by the sorry state of the West, and for Catholics tempted by the sorry state of the Church’s human element to depart from her, or to refuse due submission to the Roman Pontiff.

Socrates was so critical of his country that he was put to death by it. Yet he could have escaped execution had he wanted to. The reason he did not, as he famously explained in Plato’s

Crito

, was out of loyalty to the country of which he was so critical, and which willed to destroy him. I don’t think that Socrates’ example is, in this case, one that we are bound to follow; Aristotle did no wrong in fleeing, lest Athens sin twice against philosophy. All the same, that example is worth pondering for contemporary conservatives tempted to oikophobia by the sorry state of the West, and for Catholics tempted by the sorry state of the Church’s human element to depart from her, or to refuse due submission to the Roman Pontiff. The argument of the Crito

Socrates’ argument, in brief, is that one’s country is like one’s father or mother, so that to deny its authority over one would be like denying the authority of one’s parents. Now, to flee Athens so as to avoid execution would, Socrates continues, be tantamount to denying its authority. Hence, he concludes, it would be wrong for him to flee. However unjust, his execution was in his view something he had to suffer out of a kind of filial loyalty.

Naturally, one might object to this argument in several ways. But one objection that I think has no force is the claim that Socrates is being inconsistent. In Plato’s Apology, Socrates had, of course, refused to submit to the command that he cease philosophizing. Continuing to philosophize was, he argued, required by obedience to a higher law than that of Athens. Because of this, it is often suggested that there is a tension between the views presented in the two dialogues. (This has come to be known as “the Apology-Crito problem.”) But the parental analogy shows, in my view, why there is no genuine inconsistency here.

Suppose you are a minor and your father commands you to do something immoral – to steal a bottle of whiskey from the supermarket, or to bully other children, or whatever. You ought to disobey those particular unjust commands. But that doesn’t entail that he is no longer your father or that you can in general deny his authority over you. He is still owed the minimal respect that any father is owed. He still possesses the general authority over you that a father has over a child, and still ought to be obeyed when his commands are lawful. And you may have to suffer unjust punishments for your refusal to obey particular unjust commands. For example, if he grounds you for a week for refusing to steal, you’ll just have to grin and bear it until you reach adulthood and are no longer under his authority.

Obviously there are going to be extreme cases (such as those involving sexual or extreme physical abuse) where a parent ought to lose custody of a child. I put those cases aside for present purposes, and focus just on the less extreme sort of case, in order to understand Socrates’ argument. The general principle he is appealing to, it seems to me, is that in the case of parental authority, it is possible for a child to have a right to refuse obedience to a specific unjust command while still having no right to deny a parent’s generalauthority over one. And he argues for a parallel to his relationship to Athens. He is saying that even though he has a right and indeed a duty to disobey certain specific commands (such as the command to cease philosophizing), it does not follow that he has a right to reject the city’s generalparental-like authority over him (as, he thinks, he would be doing if he fled the city in order to avoid execution). Hence there is no inconsistency between the positions he takes in the Apology and the Crito.

That doesn’t by itself guarantee that the argument is, at the end of the day, correct. One might still challenge the assumption that the city is relevantly like a parent. Or one can accept this assumption, but then argue that the injustice in the case of Socrates’ execution is so grave that the city is acting like an extremely abusive parent, who ought to lose “custody” of Socrates (so that he can justly flee). My point is just that I don’t think the charge that Socrates is being inconsistentis a good objection.

Now, in fact Socrates is also on strong ground in comparing one’s country to one’s parents. Modern readers, who tend to think of politics in terms of the individualist “social contract” model inherited from Hobbes and Locke, are bound to find this odd. But from the point of view of classical political philosophy, for which human beings are by nature social animals, the family is the model for social life in general and parental authority the model for political authority. Hence, for Aquinas (and indeed for Catholic social teaching more generally) patriotismand a general respect for public authorities are moral duties falling under the fourth commandment.

Suffering for one’s country

The weakness in Socrates’ argument is rather that he takes it too far. Again, even in the case of literal parents, it is possible for them to lose their authority over a child when the abuse is sufficiently egregious. And the analogy between one’s country and one’s parents is in any event not an exact one, insofar as one’s duties to one’s country are weaker than those to one’s parents. Hence the threat of unjust execution would in fact justify Socrates in fleeing the city.

All the same, there is a nobility in Socrates’ decision, and if he goes too far in one direction, it is also possible to go too far in the other direction. What Socrates gets right, I would argue, is that there is at least a presumption in favor of being willing to suffer injustice fromone’s country for the sake of one’s country. And this flows from a filial love and duty that is at least analogous to the love and duty one owes one’s parents. The presumption can be overridden when injustice has too deeply permeated the basic institutions of one’s country. But the presumption is nevertheless there, and we are duty-bound to be careful lest we judge too hastily that it has been overridden.

The “Don’t tread on me” spirit of traditional American thinking about political matters can blind us to this presumption. I’m not entirely knocking that spirit; I largely share it myself, and it has its salutary aspects insofar as Americans are sometimes less inclined than others are to go along with idiotic and immoral governmental policies (like open-ended lockdowns, for example).

But at least in the view of some observers, some right-wingers have judged that “wokeness” has so thoroughly corrupted our country and civilization that they no longer merit our loyalty. And in my view this is a rash and irresponsible judgment. That is by no means to deny the danger of wokeness, which I regard as a satanic menace that cannot be compromised with. Wokeness delenda est. But it is, to say the least, premature to judge that this menace will win the day, as is manifest from the revulsion that its excesses have generated in the electorate.

Twenty-five years ago, Fr. Richard John Neuhaus’s First Things magazine generated a fierce intra-conservative controversy by raising the question of whether the principles governing the American judicial system might at some point become so contrary to the natural law that citizens will no longer owe it their allegiance. This is an even more serious question today than it was then, and the debate merits re-reading. All the same, it is premature now, as it was then, to judge that we have reached the dreaded point of no return. We clearly have not – as is obvious from the fact that we still have the freedom to discuss the matter.

Our forebears literally shed their own blood to save their country from tyranny. It would be the most contemptible softness and “sunshine patriotism” to think that (say) getting kicked off Twitter, or being required to wear a mask – obnoxious as these things are – mark the End of Democracy and absolve us from any further loyalty to our country and its institutions. Yes, wokeness is a monster. So we should work to save our country from it, rather than retreating into a fantasyland of crackpot conspiracy theories and political fanaticism and sympathy with the West’s enemies.

Suffering for the Church

Loyalty to country is not absolute, but loyalty to the Church must be, because unlike one’s country, she is divinely protected from total corruption. The project of saving one’s country from tyranny and decadence can fail. The project of saving the Church from bad prelates and heretics cannot fail. To despair of such salvation – to fret that the problems remain unresolved after ten or fifty or a hundred years – is to sin against the virtues of faith and hope, which demand of us that we take the long view.

But it is also a sin against charity. It is a shallow love which endures only to the extent that the beloved remains attractive. Caritas demands more. As St. Paul wrote, “perhaps for a good man one will dare even to die. But God shows his love for us in that while we were yet sinners Christ died for us” (Romans 5:7-8). Similarly, we must love and pray for our own enemies, and not just our friends and families. How much more must we love the Church, even when her human element is dominated by immoral and faithless men? Indeed, especially then, since this is when the Church most needs us? How much more must we love and uphold the foundation of the Church, the papacy, even when (and again, especially when) the office is held by someone who fails to do his duty? And yet there are those Catholics whose personal disappointments lead them to abandon the Church, and those who strain to find fanciful rationalizations for refusing submission to Christ’s vicar.

This is not to deny for a moment that there can be legitimate respectful criticism of the Church’s authorities, including the pope, as the Church has always recognized. But if such criticism does not have the desired effect, then the only option is patient forbearance rather than picking up one’s marbles and stomping off. As the instruction Donum Veritatis teaches:

For a loyal spirit, animated by love for the Church, such a situation can certainly prove a difficult trial. It can be a call to suffer for the truth, in silence and prayer, but with the certainty, that if the truth really is at stake, it will ultimately prevail.

We find here too a parallel with Socrates, who simultaneously criticized the governing authorities while refusing to subvert their authority, even to the point of submitting to unjust punishment. But the more apposite parallel is to Christ. As Socrates rebuked Crito, so too Christ rebuked Peter, who similarly, and wrongly, urged him not to put up with the injustice that the authorities of his day sought to inflict on him: “Get behind me, Satan! You are a hindrance to me; for you are not on the side of God, but of men” (Matthew 16:23).

Edward Feser's Blog

- Edward Feser's profile

- 329 followers