Edward Feser's Blog, page 22

August 11, 2022

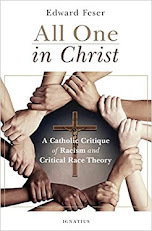

All One in Christ

My new book All One in Christ: A Catholic Critique of Racism and Critical Race Theory is out this month from Ignatius Press. If you are someone who prefers to order directly from the publisher, you can now do so. You can also order via Amazonand Barnes and Noble. In September, a German translation of the book will be published by Editiones Scholasticae.

My new book All One in Christ: A Catholic Critique of Racism and Critical Race Theory is out this month from Ignatius Press. If you are someone who prefers to order directly from the publisher, you can now do so. You can also order via Amazonand Barnes and Noble. In September, a German translation of the book will be published by Editiones Scholasticae. Here’s the table of contents:

1. Church Teaching against Racism

2. Late Scholastics and Early Modern Popes against Slavery

3. The Rights and Duties of Nations and Immigrants

4. What is Critical Race Theory?

5. Philosophical Problems with Critical Race Theory

6. Social Scientific Objections to Critical Race Theory

7. Catholicism versus Critical Race Theory

Advance reviews:

“This is the best book I've read on the topic. Ed Feser writes in accessible yet nuanced ways to demonstrate the philosophical and theological errors of both racism and Critical Race Theory.” Ryan T. Anderson, President, Ethics and Public Policy Center

“There is not a better book on the subject from a Catholic perspective. All One in Christ should be required reading for any Catholic prelate, parent, principal, or college president.” Francis J. Beckwith, Professor of Philosophy and Church-State Studies, Baylor University

“Feser's account of the Church's opposition to slavery is authoritative, but it is his devastating takedown of Critical Race Theory that makes this book so special.” Bill Donohue, President, Catholic League for Religious and Civil Rights

“Dr. Feser shows the consistent magisterial emphasis on the dignity of every human person and brilliantly articulates the Church's clear and unambiguous teaching against racism. An absolute must-have for all Catholics who want to be well informed about racism and Critical Race Theory.” Deacon Harold Burke-Sivers, Author, Behold the Man: A Catholic Vision of Male Spirituality

“Edward Feser reveals that Critical Race Theory, by its own definition, embraces partiality, thus making it clear that this theory is in no way an answer to racism, but is, in fact, a covert form of racism.” Rev. Walter B. Hoye, Founder, Issues4Life Foundation

“A careful examination of Critical Race Theory that goes beyond the political and journalistic squabbles to fundamental questions of truth and justice. Ed Feser maintains steadiness and balance as he brings faith and reason to bear on the most heated public controversies.” Robert Royal, Author, A Deeper Vision: The Catholic Intellectual Tradition in the Twentieth Century

“Edward Feser offers an analysis that helps Catholics better understand the Church's stance on racism and uphold the inherent dignity of each human Being.” Fr. John M. McKenzie, National Shrine of the Little Flower Basilica

August 5, 2022

Benedict contra Benevacantism

I’ve been reading the second volume of Peter Seewald’s Benedict XVI: A Life. There is much of interest in it, including a new interview with Benedict at the very end. Some of what he says is relevant to the controversy over Benevacantism (also called “Beneplenism” and the “Benedict is pope (BiP)” thesis), which holds that Benedict never validly resigned and that Francis is an antipope. I’ve addressed this topic a couple of times before and the debate is, in my view, essentially played out. But since a small but significant number of Catholics remain attracted to this foolish thesis, it seems worthwhile calling attention to how Benedict’s remarks throw further cold water on it.

I’ve been reading the second volume of Peter Seewald’s Benedict XVI: A Life. There is much of interest in it, including a new interview with Benedict at the very end. Some of what he says is relevant to the controversy over Benevacantism (also called “Beneplenism” and the “Benedict is pope (BiP)” thesis), which holds that Benedict never validly resigned and that Francis is an antipope. I’ve addressed this topic a couple of times before and the debate is, in my view, essentially played out. But since a small but significant number of Catholics remain attracted to this foolish thesis, it seems worthwhile calling attention to how Benedict’s remarks throw further cold water on it. Who is the current pope?

Seewald reports that in a 2018 exchange, Benedict refused to answer certain questions about the current situation in the Church, on the grounds that this would “inevitably be interfering in the work of the present pope. I must avoid and want to avoid anything in that direction” (p. 533, emphasis added). That remark by itself demonstrates that Benedict does not regard himself as still pope. For if he were, then he could hardly be interfering with himself by speaking out. Benedict also explicitly rejects “any idea of there being two popes at the same time,” since “a bishopric can have only one incumbent” (p. 537). Who does he think is the one current pope, then? The answer is obvious from the fact that Benedict explicitly refers to Francis as “Pope Francis” three times in the interview (at pp. 537 and 539). He also refers to Francis as “my successor” (p. 539), and speaks of “the new pope” (p. 520).

Clearly, then, Benedict himself thinks that he is not the pope and that Francis is the pope. Now, Benevacantists claim to submit loyally to the authority of the true pope, who, they say, is still Benedict. They also think that Francis’s alleged status as an antipope explains his predilection for doctrinally problematic statements. But then, if Benevacantists submit to Benedict’s authority, shouldn’t they accept his judgment that Francis is the pope and he is not? Of course, that would be an incoherent position. Benevacantists must, accordingly, judge that Benedict is simply mistaken.

But that just leads them out of one incoherent position and into another. For if Benedict’s understanding of the nature of the papal office is so deficient that he does not even realize that he is himself pope, and instead embraces an antipope, how is he any more reliable as a teacher of doctrine than Francis? Wouldn’t this grave doctrinal error indicate that he is an antipope? Wouldn’t his being in communion with an antipope entail that he is also a schismatic, and indeed that he is in schism with himself? Wouldn’t his failure to appoint cardinals validly to elect his successor (instead leaving it to the alleged antipope Francis invalidly to make such appointments) entail that he has essentially destroyed the papal office for all time, by making it impossible ever again to have a valid papal election? How, given all of this, can Benevacantists still regard Benedict as a hero any more than they regard Francis as such? How can they avoid going full sedevacantist?

Emeritus schmeritus

Benevacantists make much fuss about Benedict’s adoption of the “Pope Emeritus” title, taking it to be evidence that he intended to retain some aspect of the papal office. I have explained elsewhere why the title indicates no such thing, and Benedict’s remarks in the interview confirm this. Commenting on the use of “emeritus” to refer to a retired bishop, Benedict says that “the word ‘emeritus’ said that he had totally given up his office,” and retained only a “spiritual link to his formerdiocese” as its “former bishop” (p. 536, emphasis added). In taking the “Pope Emeritus” title, he was simply extending this preexisting usage to the specific case of the bishop of Rome.

That entails, though, that Benedict understands himself to have “totally given up” the papal office, and takes Rome to be his “formerdiocese.” This undermines claims to the effect that his resignation was invalid, on the grounds that he wrongly supposed that he could give up one aspect of the office (the “ministerium”) while retaining another (the “munus”). He was supposing no such thing – again, if he had been, he could not think of Rome as his former diocese, the bishopric of which he had totallygiven up.

Speaking of the disappointment that his resignation caused, Benedict says that, nevertheless, “I was clear that I had to do it and that this was the right moment. Otherwise, I would just wait to die to end my papacy” (p. 520). Notice that he takes his resignation to have ended his pontificate no less decisively than his death would have ended it. Needless to say, had he died, there would be no talk of him holding on to the “munus” while giving up the “ministerium.” But if he takes his resignation to have ended his papacy just as completely as his death would have, then in that case too he cannot be said to have intended to hold on to the one while renouncing only the other.

Proponents of the munus/ministerium distinction claim that Benedict laid down only the functions of the papacy, while holding on to its ontological status, which they claim he thinks cannot be given up. But in his interview with Seewald, Benedict explicitly rejects the very idea that these can be separated. In response to the question whether failing capacity is a good reason to resign the papacy, Benedict says:

Of course, that might cause a misunderstanding about function. The Petrine succession is not only linked to a function, but also concerns being. So functioning is not the only criterion. On the other hand, a pope must also do particular things… [I]f you are no longer capable it is advisable – at least for me, others may see it differently – to vacate the chair. (pp. 524-25)

Clearly, then, he takes the being and the function of the papacy to go hand in hand, so that if one renounces the one – “vacates the chair” – one thereby renounces the other.

It is also sometimes suggested that Benedict’s resignation was done under duress and thus invalidly. To that he responds:

Of course you can't submit to such demands. That is why I stressed in my speech that I was doing so freely. You can never leave if it means running away, you can never submit to pressure. You can only leave if no one is demanding it. And no one has demanded it in my time. No one. It was a complete surprise to everyone. (p. 506)

There simply can be no reasonable doubt, then, that Benedict’s resignation met the very simple criteria set out in canon law: “If it happens that the Roman Pontiff resigns his office, it is required for validity that the resignation is made freely and properly manifested but not that it is accepted by anyone” (Can. 332 §2). He clearly intended to renounce the office entirely, not merely in part. And he did so freely. End of story.

Prayer and providence

Benevacantists are extremely dismayed at the state of the Church and the world, and rightly so, because both are in ghastly shape. It is this, I submit, that helps explain their tenacious attachment to a theory that collapses pretty quickly on close inspection. Benevacantism seems to provide a solution to the difficulties posed by Francis’s problematic words and actions. In fact, as I have shown in previous commentary on this subject, it makes things far, far worse. But it can be emotionally satisfying, because it licenses criticizing Francis in a vituperative and disrespectful manner that would not be justifiable if he really is pope.

It is worth noting that Benedict too is clearly dismayed at the state of the Church and the world, and for the same reasons. Asked about corruption in the Curia, the Vatileaks scandal, and the like, he makes it clear that the real problems run much deeper than such things:

However, the actual threat to the church, and so to the papacy, does not come from these things but from the global dictatorship of ostensibly humanist ideologies. Contradicting them means being excludedfrom the basic social consensus. A hundred years ago anyone would have found it absurd to speak of homosexual marriage. Today anyone opposing it is socially excommunicated. The same goes for abortion and creating human beings in a laboratory. Modern society is formulating an anti-Christian creed and opposing it is punished with social excommunication. It is only natural to fear this spiritual power of Antichrist and it really needs help from the prayers of a whole diocese and the world church to resist it. (pp. 534-35)

Clearly, Benedict does not agree with those supporters of Pope Francis who pretend that concern about these matters is nothing more than a reflection of American right-wing culture war politics. On the contrary, these issues concern fundamental Christian morality and an opposition to it that derives from nothing less than the “power of Antichrist.”

Borrowing a metaphor from Gregory the Great, Benedict speaks of “the little ship of the church running into heavy storms” and proposes it as “an image of the church today, whose basic truth can hardly be disputed” (p. 537). He also says, in response to a question about the condition of the Church:

St Augustine said of Jesus’ parables about the church that, on the one hand, many people in it are only apparently so, but are really against the church… [T]here are times in history in which God’s victory over the powers of evil is comfortingly visible, and times when the power of evil darkens everything (p. 539)

Asked about whether Pope Francis should have answered the dubia submitted by four cardinals in the wake of Amoris Laetitia, Benedict declines to answer on the grounds that the question “goes into too much detail about the government of the church,” but also says:

In the church among all humanity's troubles and the bewildering power of the evil spirit, the gentle power of God's goodness can still be recognized. Although the darkness of successive eras will never simply leave the joy of being a Christian unalloyed [...] in the church and in the lives of individual Christians again and again there are moments in which we are deeply aware that the Lord loves us and that love means joy, is ‘happiness’. (p. 538)

It is hard not to see in this an attempt to offer encouragement to those disheartened by Amoris and its aftermath – and also an insinuation that the confusion that the controversy has caused in the Church reflects an attack by “the bewildering power of the evil spirit,” and the “darkness” of the present era.

If, as Benevacantists claim, Benedict really did think of himself as still possessing the munusof the papacy, it is inconceivable that he would not say and do more than he has done in the face of what he himself describes as the “heavy storms” currently facing the Church due to “the bewildering power of the evil spirit,” indeed the “spiritual power of Antichrist” which today “darkens everything.” The only plausible explanation for why he has not done so is that he believes that Francis and Francis alone is pope and that any stronger words or actions on his part would threaten schism. He obviously believes that weathering this storm requires prayer and trust in divine providence, rather than resort to crackpot theories. It is ironic that many Benevacantists mock their critics for taking precisely this attitude which Benedict himself recommends.

Related reading:

Benevacantism is scandalous and pointless

Benedict is not the pope: A reply to some critics

The Church permits criticism of popes under certain circumstances

July 29, 2022

Confucian hylemorphism

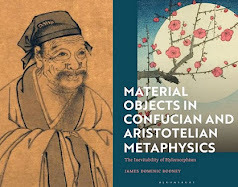

The Neo-Confucian Chinese philosopher Zhu Xi or Chu Hsi (1130-1200) famously posited two metaphysical principles often compared to Aristotle’s notions of form and matter. James Dominic Rooney defends the interpretation of Zhu Xi as a hylemorphist in his new book

Material Objects in Confucian and Aristotelian Metaphysics

. Into the bargain, he does so in conversation with contemporary analytic metaphysics and neo-Aristotelian philosophy. It’s an excellent and important book.

The Neo-Confucian Chinese philosopher Zhu Xi or Chu Hsi (1130-1200) famously posited two metaphysical principles often compared to Aristotle’s notions of form and matter. James Dominic Rooney defends the interpretation of Zhu Xi as a hylemorphist in his new book

Material Objects in Confucian and Aristotelian Metaphysics

. Into the bargain, he does so in conversation with contemporary analytic metaphysics and neo-Aristotelian philosophy. It’s an excellent and important book. What follows is a summary of some of the key ideas. Zhu Xi’s fundamental notion is the distinction between li and qi. Li can be translated as “pattern” or “structure.” It is to be understood as that which gives something what Zhu Xi characterizes as its “nature,” and thus defines the “norm” for things of its kind. Qi, by contrast, is that which receives said pattern or structure and thereby affords li an anchor in the concrete world. Lithus has a kind of priority relative to qi. For Zhu Xi, “li is one, the instances many,” and by itself is “without physical form.” Qi, meanwhile, “is unrefined and has impurities.” Liis the “reason” by which things are as they are, and thereby makes them intelligible.

Needless to say, from this much it is clear that li corresponds pretty closely to form, and qi to matter. However, there is much more to be said, because the phrases quoted so far are compatible with either an Aristotelian or a Platonist reading of Zhu Xi. To put the issue in terms familiar from contemporary analytic metaphysics, Rooney asks whether we should read Zhu Xi as offering a “constituent ontology” or a “relational ontology.” For the Aristotelian, form and matter are each themselves parts or constituents of an individual physical object. For the Platonist, by contrast, though individual physical objects are what they are by virtue of their relations to the Forms, the Forms themselves are not parts or constituents of the objects. The question, then, is whether li is itself a part or constituent of a physical object, as form is for the Aristotelian, or is instead to be conceived of along the lines of a Platonic Form.

Rooney argues for reading Zhu Xi as a constituent ontologist, and thus in a manner that parallels Aristotelian hylemorphism. (Rooney himself prefers the spelling “hylomorphism.” But nothing of substance rides on that, if you’ll pardon the pun.)

Here the exegesis of the relevant texts gets complicated, but Rooney marshals evidence for a hylemorphist reading, which includes the following. Despite li’s priority, ultimately for Zhu Xi the li and qi of a thing exist together. “Under heaven there is no li without qi or no qi without li.” He holds that “if there were no qi, then li would have no place in which to inhere.” Zhu Xi also says things that imply that qi is purely potential in the absence of li, as prime matter is for Aristotelians like Aquinas.

A complicating factor here is that “li” is used ambiguously, and has both a general sense and a particular sense. Rooney argues that it is sometimes used with reference to the “material nature” of a particular individual physical object, and sometimes instead with reference to the “fundamental nature” shared by all things. In the former sense, he holds, it is comparable to the Aristotelian notion of the substantial form of a thing of some specific natural kind, where this form is understood as a constituent of that thing.

Where li is instead understood in a more general way as the fundamental nature in which all things share, Rooney proposes that this can be interpreted as analogous to Aquinas’s notion that all things participate in God conceived of as their exemplar cause. In this way, there is in Zhu Xi’s metaphysics not only an Aristotelian element, but also something comparable to the Neo-Platonic element that Aquinas grafts onto his own Aristotelianism. However, though we arguably can interpret Zhu Xi’s “Heavenly Li” something analogous to Aquinas’s notion of God as subsistent being and source of all other reality, there is no attribution to it of intellect and will (as there is for Aquinas).

These are, again, just some general themes, and don’t convey the richness of Rooney’s discussion of the relevant classic texts and scholarly literature on them, not to mention his broader defense of hylemorphism and treatment of issues in contemporary analytic metaphysics. This kind of high-level engagement of Western with non-Western traditions is much needed, and by carrying it out at book-length, Fr. Rooney has made a major contribution.

Related posts:

July 23, 2022

Mullins strikes out

My new Philosophy Compass article “The Neo-Classical Challenge to Classical Theism” responds to several criticisms of classical theism and the doctrine of divine simplicity that have been raised by Ryan Mullins. At Joseph Schmid’s Majesty of Reason blog, Mullins has replied to the article. What follows is a rejoinder.

My new Philosophy Compass article “The Neo-Classical Challenge to Classical Theism” responds to several criticisms of classical theism and the doctrine of divine simplicity that have been raised by Ryan Mullins. At Joseph Schmid’s Majesty of Reason blog, Mullins has replied to the article. What follows is a rejoinder. Mullins’ reply can be found in the first part of the post (titled “Mullins Strikes Back”). The second part is a reply by Schmid. Because my article was directed at Mullins rather than Schmid, and because Mullins’ reply (and this rejoinder of mine) are already quite long as it is, I am in the present post going to confine my attention to Mullins’ remarks. I intend no disrespect to Schmid. But I have been meaning anyway to write up a reply to his recent article on my Neo-Platonic argument for God’s existence (to which he refers in this latest piece). So I will put off commenting on Schmid until I am able to get to that.

The neo-classical tradition

Regrettably, Mullins is needlessly aggressive right out of the gate, and begins with a gross mischaracterization of an earlier exchange between us. Rather than take the bait, I will simply direct the interested reader to the response I gave at the time to the false accusations that he repeats in this latest piece.

Mullins starts his reply to my Philosophy Compassarticle with a section devoted to arguing that the neo-classical position is more prevalent in the theistic tradition than its critics acknowledge – though “arguing” is a generous way of putting it. In fact, the section is little more than a long string of tendentious and undefended assertions about what the Old Testament and various Islamic thinkers allegedly say about issues like divine timelessness and divine simplicity.

For example, Mullins claims that elements of classical theism like its commitment to divine simplicity are “anti-biblical,” and cites several scholars who make similar assertions. This is meant to establish that the neo-classical position is as old as the Pentateuch. But of course, classical theists would not agree that their position is anti-biblical, and can also cite scholars in support. Moreover, Mullins doesn’t offer even a single example of a purported contradiction between classical theism and the Bible. (The closest he comes is to refer to Exodus 3:14 as a text that he thinks is incompatible with simplicity and immutability, but he doesn’t explain howit is.) Nor does he refer to, much less answer, the arguments from scripture that have been given in defense of classical theism.

I am not blaming Mullins for not getting into the minutiae of biblical scholarship in a blog post mostly devoted to philosophical issues. One can’t do everything in one article – I understand that. The problem is that he says so little that his remarks amount to nothing more than question-begging assertion. Moreover, they are not really relevant in the first place to my article, which explicitly confines itself to philosophical issues and, for its limited purposes, puts the biblical considerations (however obviously important) to one side.

Only slightly less weak is Mullins’ appeal to the Islamic tradition. He lists several thinkers who he says rejected notions like divine timelessness and simplicity (though he acknowledges that there are, of course, also Islamic thinkers who embrace them). Mullins makes the remark: “Feser says that if you notice this obvious problem you are engaged in question begging. How dare these people notice obvious problems!”

I don’t object to sarcastic quips when they are merited, or at the every least intelligible, but this one is neither. I honestly have no idea what Mullins is referring to here. In my Philosophy Compass article, I say nothing at all about the Islamic tradition apart from a passing reference to Avicenna. And while there are a couple of places where I accuse Mullins of begging the question (namely, in his formulations of the Creation and Modal Collapse objections), I do not do so in connection with the topic at issue here. So, again, I simply don’t know what he is talking about.

The substantive question is whether the particular Islamic thinkers Mullins cites really have the views he attributes to them. Some of them do, but in any event here too Mullins simply makes assertions rather than offering any specific texts in support. And judging from Mullins’ habit of misrepresenting the views of other thinkers (examples of which I gave in my Philosophy Compass article), it would be foolish not to take his assertions here with a grain of salt. But I will leave the question of whether he gets this or that particular Islamic thinker right to those who know their work better than I do. (Those following this debate on Twitter will have noted that Khalil Andani has criticized Mullins’ claims about the views of Razi and Juwayni, as well as his appeal to Karramism.)

Anyway, if what Mullins intends to establish is simply that views that are now characterized as marks of a “neo-classical” approach can be found in some thinkers well before contemporary philosophy of religion, then I am happy to concede that point, though I never denied it. (Indeed, I have often cited William Paley as an example of an earlier thinker who departed from classical theism.) When, in my article, I said that “neo-classical theism in the current usage of that term is a recent arrival,” what I meant is that it is recent as a self-conscious movement or school of thought, going by that particular name, and distinguishing itself from earlier schools critical of classical theism such as process theism, panentheism, and open theism. I did not mean to deny that neo-classical theists could plausibly find some precursors of their distinctive position earlier in the tradition, and I wish I had made that clearer.

Misrepresenting Aquinas

All of this is, in any event, tangential to my main disagreement with Mullins, which is not about the history or prevalence of neo-classical views, but rather about the core neo-classical objections to classical theism. Indeed, my article has a much more specific focus even than that, emphasizing that the objections raised by Mullins and others fail when directed at the Thomisticversion of classical theism, specifically. And part of the problem, as I show in the article, is that Mullins badly misunderstands key aspects of the Thomistic position. Here is how Mullins begins his response:

You are probably familiar with a particular trope by now. Internet classical theists will respond to all objections by saying, “You have misunderstood Aquinas.” This is something that we joke about often. We have made so many memes making fun of this incredibly tired response to any and all objections.

End quote. Now, I like memes and other hijinks as much as the next guy, as is evident from my use of comic book panels, Photoshopped images, and the like here at the blog. But there is a time and a place for that sort of thing, and these remarks strike me as a sophomoric way to begin a response to a straightforward, non-vituperative academic article that treats Mullins and his views with respect, even if critically. They are especially rich given that Mullins starts out his post with the claim that I had misrepresented himin our earlier exchange (which I had not, but that he’s still upset about the matter makes his complaint about alleged Thomist oversensitivity to misrepresentation ring hollow). Moreover, Mullins goes on to acknowledge: “To be clear, there can be cases of misunderstanding the classical tradition, and it is a good thing to point those out when they arise.” But then the thing to do, surely, is just to address head-on the claims that he has misrepresented Thomists, and put the trash talk to one side.

Perhaps the reason Mullins does not do so is that the claims are in fact unanswerable. Consider this passage from my article:

In a series of writings, Mullins has claimed that the doctrine of divine simplicity holds: that God has no properties at all (2013, p. 189; 2020, p. 17; 2021, pp. 88 and 93); that this entails that he does not have even extrinsic or relational properties, sometimes known as Cambridge properties (2013, p. 183; 2021, pp. 87–88 and 93); that we cannot make even conceptual distinctions between parts or aspects of God (2013, p. 185; 2021, p. 90); that God therefore cannot even be said to be Lord or Creator (2013, p. 200; 2020, p. 27); and that when God is said to be “pure act” without potentiality, what this means is that God is an act or action, in the sense of something a person does (2013, p. 201)…

But the trouble with such objections, from the point of view of Thomistic classical theists, is that the claims Mullins makes about the doctrine of divine simplicity are false, or at best extremely misleading. The doctrine seems incoherent only because he is mischaracterizing it. (Emphasis added)

End quote. Please note carefully that what I say here is that Mullins’ characterization of classical theism does not correspond to what Thomistic classical theists, specifically, would say. I also repeatedly emphasize in the article that Mullins relies too heavily for his understanding of classical theism on the work of Katherin Rogers, who is a non-Thomist classical theist. But here is how Mullins responds to my criticism:

I do not claim these things, I report them. I directly quote a bunch of classical theists saying all of this in my publications. I’m not pulling these notions out of thin air…

[A]ll of my explicit quotes from classical theists are completely ignored by Feser, and now he is saying that I am making false claims. That is curious to say the least…

According to Feser, I claim that classical theism says that God does not have properties. Feser says that this is not an accurate portrayal of classical theism (p. 3). I find this really wild since I have repeatedly quoted Katherin Rogers explicitly saying that God does not have properties.

End quote. I trust the reader will have noticed the sleight of hand. What is in question is whether Mullins gets Thomist classical theists right. But what he says in his defense is that he has provided supporting quotes from non-Thomistic classical theists, such as Rogers. And he claims that I ignore this purported evidence in his favor. The problem, needless to say, is that quotes from non-Thomists are not evidence for what Thomists think. But all the same, I did not ignore his citations of non-Thomist classical theists, but indeed called attention to them myself. For example, I explicitly cite his reliance on Rogers no fewer than five times (in the main text of the article at page 2, and in the endnotes in notes 5, 16, 23, and 27).

Of his dependence on Rogers, Mullins says:

I will admit that I have relied quite heavily on one of the greatest living classical theists for my own understanding of classical theism. Rogers is widely regarded as an excellent medieval scholar, and relying on her work is what responsible scholarship demands.

End quote. Now, I intend no offense at all to Prof. Rogers, who is indeed a fine scholar from whose work I have also profited. But she is just one scholar, and her views are hardly representative of the classical theist tradition in general. Moreover, Rogers is an Anselm specialist, but as she herself acknowledges (as I note in my article) it is Aquinas rather than Anselm who has given the clearest expression of the central classical theist doctrine of divine simplicity. Nor, needless to say, is Rogers infallible. Mullins himself writes:

I do have various disagreements with her understanding of various topics. For example, Rogers thinks that Anselm affirms an eternalist ontology of time. I disagree. In The End of the Timeless God, I offer an extended exegesis of the classical Christian tradition to argue that thinkers like Anselm affirmed a presentist ontology of time.

End quote. Here, as it happens, I agree with Mullins rather than Rogers about how to interpret Anselm. Now, if Rogers can, by Mullins’ own admission, get even Anselm wrong (despite being a specialist on Anselm), then surely it is possible for her to get Aquinas wrong. Yet Mullins depends on Rogers, in part, for his understanding of Aquinas. Take, for example, the claim that when Aquinas characterizes God as “pure act,” what he means is that God is an action in the sense of an act a person carries out. I think it fair to say that any Thomist would regard this as a howler, about as bad a misreading of Aquinas as can be imagined (for reasons I explain in my article). So, where did Mullins get this misreading? From Rogers, as I also note in the article.

Mullins makes the ad hominem suggestion that the reason I and other Thomists are less keen than he is on Rogers’ views might be that we think she concedes too much to the Modal Collapse Objection. Well, I certainly think she concedes too much to it, but what matters for present purposes is that she just gets Aquinas wrong. In any case, Mullins does not see that the ad hominem can be flung right back at him. For I would propose that the reason Mullins overemphasizes Rogers’ work is precisely that portraying her views as representative of classical theism in general gives his objections (including the Modal Collapse Objection) greater rhetorical force than they otherwise would have.

Misrepresenting Thomists

Mullins goes on throughout his reply to cite a number of other non-Thomist classical theists whose views he claims correspond to his characterization of classical theism. Indeed, this makes up the bulk of his reply. In some cases I would dispute his interpretation of their views, but in any event all of this is irrelevant to the argument of my paper, which, again, focuses on the point that Mullins misrepresents Thomistic classical theism in particular.

Now, Mullins does also make at least a cursory attempt to support his position by citing Thomists. For example, in defense of his claim that classical theism takes God to lack any properties at all, he writes: “Even on page 4 of Feser’s article he quotes Brian Davies saying that God lacks properties and attributes.” But here’s what I actually wrote, and what Davies actually says:

Davies refers to “attributes or properties of God” (2021, p. 10). To be sure, he also says in the same place that God “lacks attributes or properties distinguishable from himself and from each other” and that “God does not, strictly speaking, have distinct attributes or properties” but “is identical with them” (emphasis added). But again, to say that God and his properties are all identical is very different from saying that he has no properties at all.

End quote. Note that Mullins conveniently omits the crucial qualifying phrases “distinguishable from himself and from each other” and “distinct,” which dramatically change the meaning of the assertion he attributes to Davies. Davies, again, does not say that God has no properties, full stop; he says that God has no properties that are distinct, or that are distinguishable from himself and from each other.

In response to my claim that Thomists allow that God has Cambridge properties, Mullins says:

Aquinas in SCG Book II.12-14… is worried about God changing relationally. There Aquinas says that the relations “are not really in Him, and yet are predicated of Him, it remains that they are ascribed to Him according only to our way of understanding.” In this section, Aquinas is clear that the relations cannot be accidents in God because God does not have any accidents. In light of this, it makes no sense for Feser to say that classical theists believe that God has accidental relational properties.

End quote. What Mullins conveniently omits is what Aquinas immediately goes on to say:

And so it is evident, also, that such relations are not said of God in the same way as other things predicated of Him. For all other things, such as wisdom and will, express His essence; the aforesaid relations by no means do so really, but only as regards our way of understanding. Nevertheless, our understanding is not fallacious. For, from the very fact that our intellect understands that the relations of the divine effects are terminated in God Himself, it predicates certain things of Him relatively; so also do we understand and express the knowable relatively, from the fact that knowledge is referred to it.

End quote. Yes, as Mullins points out, Aquinas would not say that the relations between created things and God are “accidents in God.” But nobody is claiming otherwise. The claim of those Thomists who maintain that we can predicate Cambridge properties of God is rather that we can truly “predicate certain things of him relatively,” as Aquinas puts it here.

In any event, Mullins goes on to acknowledge after all that some Thomist classical theists do in fact attribute Cambridge properties to God. He writes:

Here is the thing. I know that Feser, Stump, and Miller love to play the magical card called “Cambridge properties” to solve all of their problems. Following the lead of Brian Leftow, I just don’t understand how this magical card solves anything.

End quote. Here we have a bait and switch. The specific question I was addressing was whether Mullins is correct to hold that classical theists maintain that God has no properties at all, not even Cambridge properties. I showed that this is not true of all classical theists, and in particular not true of Thomist classical theists. In his reply, Mullins at first gives his readers the impression that I am wrong and that I have ignored the evidence showing that I am wrong. But here he concedes that I am right, yet then tries to change the subject.

To be sure, whether the appeal to Cambridge properties really can, at the end of the day, do the work the Thomist claims it does is a fair enough question. But again, it is not the question that was at issue. Furthermore, Mullins does little to show that the appeal fails, despite sarcastic remarks like the one just quoted. Moreover, the Thomist who has developed the appeal to Cambridge properties in the greatest detail is Barry Miller. And Mullins admits that Miller is someone whose work he has not much engaged with. But no one who has failed to engage with Miller can seriously claim to have shown that the appeal to Cambridge properties does not do the work Thomists claim it does.

One substantive argument Mullins does give in this connection is the following:

[C]lassical theists like… [Paul] Helm understand something that Feser does not. They understand that only temporal beings with temporal location are capable of undergoing Cambridge changes. This is because Cambridge changes demarcate a before and after in the life of the thing undergoing a mere relational change. A timeless God cannot have a before and after.

End quote. But once again Mullins has failed to read my paper carefully, because I not only explicitly address Helm’s point (in endnote 19) but agree with it! In particular, I agree with him that God does not have Cambridge properties of a temporal or spatial sort. But I also note there that Mullins wrongly attributes to Helm the stronger claim that God lacks Cambridge properties of any sort at all, which does not follow and is not what Helm actually says in the passages Mullins cites.

Mullins says that for Aquinas, “God’s act of creation is intrinsic to God, and identical to God. In which case, that is the exact opposite of a Cambridge property which is an extrinsic relation that is outside of God,” and he offers quotes from Aquinas to back up the claim. But here he simply ignores the point that Christopher Tomaszewski makes about this sort of argument (and which I refer to in my article), which is that it fails to distinguish God’s creative act (a) considered qua act and (b) considered qua act of creation. Considered simply qua act, God’s act of creation is intrinsic to him; but considered qua act of creation it is a Cambridge property.

As Mullins’ article progresses, the sarcasm level increases and it finally degenerates into a rant. We get passages like this:

I have never been particularly interested in critiquing Thomism like Feser wants me to. Why? Because Aquinas’s disciples have created a million different schools of Thomism, and I have never been fussed about trying to sort through them all. This is mainly because these disciples start with an assumption that I cannot accept, and then interpret Aquinas accordingly. This is how disciples of Aquinas work. First, they start with the assumption that Aquinas cannot possibly be wrong about anything, and that he is never inconsistent with himself. Second, from this assumption, they will engage in all sorts of wild interpretative strategies to make Aquinas infallible. I just don’t have enough faith to be a fellow disciple.

End quote. But no one is asking Mullins to regard Aquinas as infallible or even to agree with him at all, nor does anyone expect him to become an expert on all things Thomist. What I was urging in my article was something much more modest, indeed so modest that no reasonable person could object to it (which, I suspect, is why Mullins prefers to attack this strawman). It was just this: If you are going to make bold and sweeping assertions about classical theism in general, as Mullins routinely does, then what you say ought correctly to describe the views of a major classical theist like Aquinas and those who follow him.

Aquinas is, after all, regarded even by many non-Thomists as the greatest of medieval philosophers, and in Catholic theology his stature is second to none. In contemporary philosophy and theology, Thomists are at least as prominent among defenders of classical theism as anyone else, if not more prominent. Rogers herself – on whom, again, Mullins has by his own admission “relied quite heavily” for his understanding of classical theism – says that it is Aquinas, rather than her own favorite classical theist Anselm, who has given the “clearest expression” of the central classical theist doctrine of divine simplicity. Agree with him or not, and agree with classical theism or not, understanding the views of Aquinas and other Thomists is crucial to understanding what classical theism actually says, and what could be said in favor of it, even if one nevertheless ends up rejecting it all.

Hence, it is simply ludicrous for Mullins confidently to claim to have refuted classical theism in general while at the same time getting Aquinas’s views badly wrong and largely ignoring the work of contemporary Thomists, then glibly dismissing the complaints of those who call him out for this. It is like boldly claiming to have refuted dualism while misrepresenting the views of Descartes and ignoring contemporary thinkers like Swinburne and Hasker, or claiming to have refuted liberalism while saying little about Rawlsianism. I would urge Mullins to devote less time to “ma[king] so many memes making fun” of his opponents, and more time to carefully reading and trying to understand what they actually say.

Related reading:

A further reply to Mullins on divine simplicity

July 20, 2022

The neo-classical challenge to classical theism

My article “The Neo-Classical Challenge to Classical Theism” has just been published at Philosophy Compass. The article is a response to the critique of divine simplicity and other aspects of classical theism developed by self-described “neo-classical” theists like Ryan Mullins. Here’s the abstract: The classical theist tradition represented by thinkers like Anselm and Aquinas predicates several remarkable attributes of God, most notably simplicity or lack of parts of any kind. Neo-classical theists have recently developed several lines of criticism of these attributes. But these criticisms are not effective against the historically most influential way of spelling out classical theism, which is Thomism.

My article “The Neo-Classical Challenge to Classical Theism” has just been published at Philosophy Compass. The article is a response to the critique of divine simplicity and other aspects of classical theism developed by self-described “neo-classical” theists like Ryan Mullins. Here’s the abstract: The classical theist tradition represented by thinkers like Anselm and Aquinas predicates several remarkable attributes of God, most notably simplicity or lack of parts of any kind. Neo-classical theists have recently developed several lines of criticism of these attributes. But these criticisms are not effective against the historically most influential way of spelling out classical theism, which is Thomism.

July 14, 2022

Goff’s gaffes

Philip Goff has kindly replied to my recent post criticizing the panpsychism he defends in his book Galileo’s Error and elsewhere. Goff begins by reminding the reader that he and I agree that the mathematized conception of nature that Galileo and his successors introduced into modern physics does not capture all there is to the material world. But beyond that we differ profoundly. Goff writes:

I agree with Galileo (ironic, given the title of my book) that the qualities aren’t really out there in the world but exist only in consciousness. So I don’t think we need to account for the redness of the rose any more than we need to account for the Loch Ness monster (neither exist!); but we do need to account for the redness in my experience. Following Russell and Eddington I do this by incorporating the qualities of experience into the intrinsic nature of matter, ultimately leading me to a panpsychist theory of reality.

End quote. Now, as I noted in my earlier post, this combination of views is odd right out of the gate. It starts out accepting the view that sensory qualities aren’t really there in matter. But then, noting the problems this raises, it proposes that the solution is to hold that sensory qualities… really arethere in matter after all! Only, not in the way we thought they were, but instead in some totally bizarre way that creates further problems without solving any (which is indeed what Goff’s view does, as I’ll show below).

This is comparable to thinking about killing someone, and then, noting how problematic this would be, proposing that after the murder we look for some way to resuscitate the corpse, Frankenstein-style. All despite the fact that this will leave us with a grotesque patchwork of a human being rather than the original person! How about just not killing him in the first place? Similarly, if you are going to end up having to put the sensory qualities back into matter after all, why not just refrain from taking them out?

Goff thinks he has a positive argument for taking them out, which I’ll come to in a moment. But first let’s note what he says is the problem with not taking them out:

Feser, in contrast, rejects Galileo’s initial move of taking the qualities out of the external world. The redness really is in the rose, the greenness really in the grass, etc., and hence we have a ‘hard problem’ not just about consciousness but also about the qualities in external objects.

End quote. This is the reverse of the truth, and Goff misses the point that rejecting Galileo’s move leaves us, not with a second “hard problem,” but rather with no “hard problems” at all. And Goff himself should see this, given his other commitments. The so-called “hard problem of consciousness” arises only if we assume that higher-level properties must be reducible to lower-level ones – that the qualitative character of a visual experience, for example, must be reducible to neurological properties or the like. There will be a corresponding “hard problem” of explaining how redness can be a feature of a rose only if we assume that redness must be entirely reducible to properties of the sort described by physics and chemistry.

But these “problems” disappear if we reject this reductionist assumption. And Goff himself rejects it, as I noted in my earlier post! He denies that all the higher-level properties of a thing must be reducible to lower-level ones. So how can he justify the claim that rejecting Galileo’s move would leave us with two “hard problems”? Indeed, how can he justify the claim that accepting Galileo’s move would leave us with even one “hard problem” that calls for the radical solution of panpsychism? Goff’s own commitments dissolve the problem, leaving the panpsychist “solution” otiose even if it didn’t have its other defects.

Let’s turn now to the positive argument Goff offers for accepting Galileo’s removal of the sensory qualities from ordinary material objects like the rose. It is an application of the traditional argument from hallucination for the indirect realist theory of perception. The character of someone’s experience of looking at a red rose might be the same whether there is really a red rose out there or instead the person is just hallucinating. Hence, the argument concludes, what the perceiver is directlyaware of in each case is really just something going on in the mind rather than in mind-independent reality (even if it is caused by something really out there in mind-independent reality).

Now, at one time I accepted this sort of argument myself (and, like Goff, was influenced in this connection by Howard Robinson, a philosopher whose work I too have long admired and profited from). But I later changed my mind. There’s a lot that can be said about the topic, and I address it in Aristotle’s Revenge (see pp. 106-113 and 340-351). For present purposes I will simply note that Goff’s conclusion is a non sequitur, as (once again) it seems to me that he ought to realize given other things he holds. For he seems to think that the argument gives us grounds for denying that anything like the red we see when we look at a rose is really out there in the rose itself. But this would not follow even if we accepted the argument from hallucination as a proof of indirect realism. After all, Goff himself allows that the rose itself really is out there. He doesn’t think that (what he takes to be) the fact that we aren’t directly aware of the rose (but only of the mind’s perceptual representation of the rose) casts any serious doubt on the reality of the rose. So, why would the claim that we aren’t directly aware of the rose’s redness show that we have reason to doubt that there is something corresponding to it out there in mind-independent reality, in the rose itself?

In short, even if we buy indirect realism, the rose itself (by Goff’s own admission) still exists in a mind-independent way. And by the same token, for all Goff has shown, even if we buy indirect realism, the redness of the rose, as common sense understands redness, still exists in a mind-independent way. The argument from hallucination for indirect realism thus turns out to be something of a red herring (pun not intended but happily noted).

Finally, Goff says:

[Feser] doesn’t in fact consider my main argument for panpsychism, which is a simplicity-based argument. I have argued that panpsychism is the most parsimonious theory able to account for both the reality of consciousness and the data of third-person science.

End quote. But actually, I did address this argument, because part of the point of the criticisms I raised was precisely that Goff’s position is not parsimonious. For one thing, as I emphasized in my original post and reiterated above, the panpsychist solution is simply unnecessary, because the problem to which it is a purported solution does not arise once we see – as Goff himself emphasizes! – that Galileo’s mathematized conception of nature is a mere abstraction that in the nature of the case cannot capture all of matter’s properties. As I noted in my original post, if you draw a portrait of someone in pen and ink, no one thinks that the absence from the black and white line drawing of many of the features that exist in the person (color, three-dimensionality, etc.) generates some deep metaphysical problem. It merely reflects the limitations of the mode of representation, that’s all. But in the same way, the absence of sensory qualities from physics’ mathematical mode of representation doesn’t pose any deep metaphysical problem either. It simply reflects the limits of mathematical representation, that’s all.

Hence Goff is like someone who looks at a black and white line drawing, notes that it leaves out many features, and then starts spinning complex metaphysical theories to “explain” the “mystery.” In both cases, there is no genuine mystery and the problem is completely bogus. And a theory can hardly be “parsimonious” if the problem it claims to solve is a pseudo-problem. (Go back to my other analogy from above. Suppose I say “Let’s kill Bob, but then find a way to bring him back to life!” And suppose you answer “How about just not killing him?” Whose plan is more parsimonious?)

For another thing, and as I also pointed out in my earlier post, panpsychism creates new problems of its own. As common sense and Aristotelianism alike emphasize, conscious experience in the uncontroversial cases is closely linked to the presence of specialized sense organs, appetites or inner drives, and consequent locomotion or bodily movement in relation to the things experienced. It is because human beings, dogs, cats, bears, birds, lizards, etc. possess these features that few people doubt that they are all conscious. And it is because trees, grass, stones, water, etc. lack these features that few people believe they are conscious.

The point is in part epistemological, but also metaphysical. Aristotelians argue that there is no point to sentience in entities devoid of appetite and locomotion, so that (since nature does nothing in vain) we can conclude that such entities lack sentience. Some philosophers (such as Wittgensteinians) would argue that it is not even intelligibleto posit consciousness in the absence of appropriate behavioral criteria. Naturally, all of this is controversial. But the point is that a theory that claims that electrons and the like are conscious faces obvious and grave metaphysical and epistemological hurdles, and thus can hardly claim parsimony, of all things, as the chief consideration in its favor!

So, Goff’s defense fails – and again, most of the problems are of Goff’s own making, because they have to do with parts of his position being inadvertently undermined by other parts. His exposure of the limits of Galileo’s mathematization of nature, his rejection of reductionism, his affirmation of external world realism, his call for parsimony – all of these elements of Goff’s position are admirable and welcome. But when their implications are consistently worked out, they lead away from panpsychism, not toward it.

July 10, 2022

Cooperation with sins against prudence and chastity

Here’s another unpublished talk which I’ve posted at my main website. It’s titled “Cooperation with Sins against Prudence and Chastity,” and I presented it at the Dominican House of Studies in Washington, D.C. in March of 2018, and at Blackfriars Hall at the University of Oxford in January of 2019. The lecture discusses Aquinas’s account of the nature of prudence or practical wisdom, and of sexual immorality as more corrosive of prudence than any other sin. It then applies this account to a critique of the pastoral advice given by some churchmen in the wake of Pope Francis’s Amoris Laetitia. That advice, I argue, amounts to cooperation with sins against chastity, and against prudence more generally. You can listen to an audio version of the lecture here.

Here’s another unpublished talk which I’ve posted at my main website. It’s titled “Cooperation with Sins against Prudence and Chastity,” and I presented it at the Dominican House of Studies in Washington, D.C. in March of 2018, and at Blackfriars Hall at the University of Oxford in January of 2019. The lecture discusses Aquinas’s account of the nature of prudence or practical wisdom, and of sexual immorality as more corrosive of prudence than any other sin. It then applies this account to a critique of the pastoral advice given by some churchmen in the wake of Pope Francis’s Amoris Laetitia. That advice, I argue, amounts to cooperation with sins against chastity, and against prudence more generally. You can listen to an audio version of the lecture here.

July 3, 2022

Problems for Goff’s panpsychism

Panpsychism is the view that conscious awareness pervades the physical world, down to the level of basic particles. In recent years, philosopher Philip Goff has become an influential proponent of the view, defending it in his books Consciousness and Fundamental Reality and Galileo’s Error: Foundations for a New Science of Consciousness . He builds on ideas developed by contemporary philosophers like David Chalmers and Galen Strawson, who in turn were influenced by early twentieth-century thinkers like Bertrand Russell and Arthur Eddington (though Russell, it should be noted, was not himself a panpsychist).

Goff’s views are bound to be of special interest to many of the regular readers of this blog, given that a critique of the conception of matter associated with Galileo and other early modern proponents of the mechanical world picture is central to his position. The problematic nature of this conception of matter has, of course, been a longstanding theme of my own work. Naturally, then, I think that Goff’s publicizing of what he calls “Galileo’s error” is an important contribution. But unfortunately, what Goff wants to put in place of that error is, in my view, not much of an improvement. Certainly his argument for panpsychism from the rejection of Galileo’s mistake is a gigantic non sequitur.

The limits of physics

Let’s begin with what Goff gets right. Common sense takes ordinary physical objects to have both (a) size, shape, motion, etc. and (b) color, sound, heat, cold, etc. Early modern philosophers and scientists characterized features of type (a) as “primary qualities” and features of type (b) as “secondary qualities,” and argued that the latter are not genuine features of matter as it is in itself, but reflect only the way conscious awareness presents matter to us. What exists in mind-independent reality is nothing more than colorless, soundless, tasteless, odorless, etc. particles in motion. Color, sound, taste, odor, etc. exist only in the mind’s experiences of that reality.

That’s the short version of the story, anyway. There are various complications. For example, on Locke’s version of the distinction, it is not quite right to say that secondary qualities don’t exist in mind-independent reality. In fact, both primary and secondary qualities are really there in physical objects. The difference is that the experiences that primary qualities generate in us really “resemble” the qualities themselves, whereas the experiences that secondary qualities generate in us do notresemble the qualities themselves. On Locke’s view, there really is something in an apple that resembles the shape you see in it, but there is nothing really there in the apple that resembles the color you see in it.

Influenced by this Lockean way of making the distinction, later philosophers would say that whether colors, sounds, heat, cold, and the like really exist in mind-independent reality depends on what we mean by those terms. If by “color” you mean a surface’s tendency to absorb light of some wavelengths while reflecting others, then you can say that color really exists in physical objects. But if by “color” you mean what common sense means by it – the perceived look of red, or blue, or whatever – then the claim is that there is nothing like that in physical objects themselves, but only in our experiences of them. Color, sound, heat, cold, etc. as common sense understands them are claimed to exist only as the “qualia” of conscious awareness, to use what has become the standard jargon.

The basic idea is clear enough however these details are worked out. Now, the reasonGalileo and the other proponents of the mechanical world picture took this view, as Goff emphasizes, is that they wanted to develop an entirely mathematized conception of nature, and while primary qualities were thought to fit comfortably into this picture, secondary qualities do not. They are irreducibly qualitative rather than quantitative, so that attempts to analyze them in purely quantitative terms always inevitably leave something out. The solution was to hold that they just aren’t really part of the natural world in the first place, but (again) only part of the mind’s perception of that world. Problem solved!

Well, not really. In fact, this move is itself problematic in several respects. One of them is that drawing a sharp distinction between primary and secondary qualities turns out to be much more difficult than it at first appears, as Berkeley famously showed. The Aristotelian philosopher, who defends common sense, would say that this is a good reason to think that secondary qualities are, after all, as objective as primary qualities. Berkeley, of course, drew the opposite conclusion that none of these qualities are really objectively out there. And he made of this claim, in turn, the basis of an argument for idealism or the denial of matter’s very existence.

The more common approach, however, was to try to make some version of the primary/secondary quality distinction work, and this went hand in hand with a Cartesian sort of dualism rather than idealism. As early modern thinkers like Cudworth and Malebranche pointed out, dualism was in fact an inevitable consequence of the primary/secondary quality distinction. For if color, sound, heat, cold, etc. as common sense understands them don’t exist in matter, then they don’t exist in the brain or the rest of the body (since those are material). And if they do nevertheless exist in the mind, then we have the dualist conclusion that the mind is not identical with the brain or with any other material thing.

The very conception of matter that modern materialism has committed itself to is therefore radically incompatible with materialism. And that is why materialists have had such a difficult time answering objections like Chalmers’ “zombie argument,” Jackson’s “knowledge argument,” and Nagel’s “bat argument,” and solving the “hard problem of consciousness” that such arguments pose for them. Attempting to develop a materialist account of consciousness while at the same time presupposing the conception of matter inherited from Galileo and Co. is like trying to square the circle. It is a fool’s errand, born of conceptual confusion and neglect of intellectual history.

Now, another lesson, and one especially emphasized by Russell and Eddington, is that the methodology that modern physics has inherited from Galileo and Co. guarantees that physics tells us far less about the material world than meets the eye. In particular, what physics reveals is only the abstract mathematical structure of physical reality, but not the intrinsic nature of the entities that flesh out that abstract structure.

Since these are all themes I have been going on about myself for many years, I am, with this much, highly sympathetic. A defense of the structural realist interpretation of modern physics and critique of the mechanical world picture are major themes of my most recent book Aristotle’s Revenge: The Metaphysical Foundations of Physical and Biological Science. These are important parts of the broader case I make there for a neo-Aristotelian philosophy of nature. Goff does not take them in that direction, but he does a real service by making better known the nature and implications of the conceptual revolution the mechanical philosophy set in motion.

Goff’s errors

After this point, however, Goff’s argument starts to fly off the rails. His next move is to borrow a further idea from Eddington and Russell, who held that introspection of one’s own conscious experiences does reveal the intrinsic nature of at least one physical object, namely the brain. That is to say, when you look within and encounter qualia – the way red looks, the way heat feels, the way a musical note sounds, and so on – what you are directly aware of are the entities that “flesh out” the abstract causal structure of the brain revealed by science.

Now, if qualia are the intrinsic properties of at least this one physical object, and we know nothing from physics about the intrinsic properties of any other part of physical reality, then, Goff proposes, we can speculate that qualia are also the intrinsic properties of all other physical reality. Physics, he says, leaves a “huge hole” in our picture of nature that we can “plug” with qualia (Goff, Galileo’s Error, p. 132). But since qualia are the defining features of conscious experience, it follows that conscious experience exists throughout the material world.

To be sure, Goff is keen to emphasize that the conscious awareness associated with, say, an electron is bound to be radically unlike, and more primitive than, ours. He also notes that a panpsychist need not attribute conscious awareness to all everyday physical objects (such as a pair of socks) but only to the more elementary bits of matter of which they are composed. Still, he is attributing something like sentience to physical reality well beyond the animal realm, indeed well beyond the realm of living things.

But this line of argument is fallacious, and the bizarre solution panpsychism proposes to the problem of how to fit consciousness into the natural world is completely unnecessary. For one thing, it is hard to imagine a more stark example of the fallacy of hasty generalization than Goff’s inference from what (he claims) brainsare like to a conclusion about what matter in general is like. Suppose we allow for the sake of argument that introspection of qualia involves direct awareness of the intrinsic properties of the matter that makes up brains. Brains are an extremely small part of the matter that makes up even just the Earth, let alone the rest of the universe (from which, as far as we know, they are entirely absent). They are also the most complex things in the universe. Why suppose that all matter, and especially the most elementary matter, is plausibly modeled on them? Surely the prima facie far more plausible bet would be that most matter is radically unlikebrains.

A second problem is that Goff’s argument takes for granted that what contemporary philosophers call “qualia” really are features of conscious experience rather than of the external objects that conscious experience is experience of. And that assumption is open to challenge. After all, common sense would take it to be obvious that when we learn what an apple tastes like or looks like, what we are learning is something about the apple itself, not about our experienceof the apple. And the Aristotelian conception of nature that the mechanical world picture displaced would have agreed.

The point is not that what seems obvious to common sense mustbe correct, but rather that it shouldn’t simply be taken for granted that contemporary philosophers’ habit of talking about the way an apple tastes, the way red looks, the way heat feels, etc. as if these were features of the mind (and thus as if they were “qualia”) – as opposed to features of mind-independent reality – reflects an accurate carving up of the conceptual territory. Goff himself emphasizes that Galileo’s treatment of these qualities as mind-dependent was motivated by his project of developing a purely mathematical conception of nature; that this was a philosophical thesis rather than one that has been established by science; and that it created the very problem of consciousness that Goff thinks panpsychism solves. Why not solve it instead by simply not following Galileo in making the conceptual move that created the problem? Goff says that “Galileo took the sensory qualities out of the physical world” and that panpsychism is “a way of putting them back” (Goff, Galileo’s Error, p. 138). Why not instead merely refrain from taking them out in the first place?

Or, if we’re going to speak of putting them back after Galileo took them out, why not put them back in the specific places he took them from? Why instead put them into every other bit of matter, including unobservable particles, when that is not where they came from? For example, Galileo (and the mechanical philosophy more generally) hold that the redness you see when you look at an apple is not in the apple itself, but only in your mind. Goff tells us that, in order to solve the problems this sort of view raises, we should say that the redness you see is in your brain, and that something analogous to it is in electrons and other particles. Why not just say instead that it really is in the apple after all, and leave it at that? Goff’s “solution” is analogous to trying to rectify the injustice caused by a theft by giving the stolen money back to everyone except the person it was taken from!

It might be replied that to reject Galileo’s move in this way would conflict with the findings of modern physics. But again, as Goff himself emphasizes, the move is at bottom philosophical rather than scientific in nature. To be sure, scientific considerations (about the physics of light, the neuroscience of vision, etc.) are relevant. But they do not by themselves establish the correctness of the mechanical philosophy’s distinction between primary and secondary qualities, because the scientific evidence is susceptible of different philosophical interpretations. Nor could Goff object that reversion to something like the conception of color, sound, etc. that prevailed before the rise of the mechanical philosophy would be too radical a departure from philosophical orthodoxy. For he acknowledges that panpsychism represents a radical departure from it, and argues that such a departure is necessary in order to solve the problem posed by Galileo’s conceptual revolution.

Moreover, some mainstream contemporary philosophers would, for reasons independent of debates about either panpsychism or Aristotelianism, defend the “naïve realist” view about qualities that was overthrown by Galileo and the mechanical philosophy. I have defended it as well. (See pp. 340-51 of Aristotle’s Revenge, which includes a discussion of the relevant contemporary literature.) Goff not only reasons fallaciously to the conclusion that conscious experience pervades inorganic reality, but reasons from assumptions about the nature of color, sound, heat, cold, etc. that his own critique of the mechanical philosophy should have led him to question.

A further problem is that the suggestion that there is something analogous to consciousness in fundamental physical particles and other inorganic entities is simply prima facie implausible, and not just because it sounds bizarre. As Aristotelians argue (see Aristotle’s Revenge, pp. 393-95), sensation is closely tied to appetite and locomotion, so that the absence of the latter from plants tells strongly in favor of the absence of sensation from them as well. What is true of plants is a fortiori true of electrons and other particles too, to which it is even more implausible to attribute appetite or locomotion. There are simply no good empirical grounds for attributing anything like sentience to the inorganic realm, any more that there are for attributing it to plants.

The attribution also turns out to be completely pointless, given other things Goff says. Consider that the panpsychist’s attribution to basic physical particles of something analogous to consciousness is alleged to make it more intelligible how the brain could be conscious. For if matter is already conscious “all the way down,” as it were, then there should be no surprise that the complex organ that is the brain is conscious too. We need simply to work out how the more elementary forms of consciousness that exist at lower levels of physical reality add up to the more sophisticated form with which we are familiar from our own everyday experience. This is known as the “combination problem,” and while Goff thinks there are promising approaches to solving it, he acknowledges that panpsychists have not yet done so.

You might suppose, then, that Goff is committed to a kind of reductionism according to which higher-level features of the natural world are intelligible only if reducible to lower-level features, where Goff differs from materialist reductionists only in positing the existence of consciousness at lower levels as well as at higher levels. But in fact, Goff explicitly rejects this reductionist assumption, citing in support the work of contemporary critics of reductionism like Nancy Cartwright. Goff allows that physical objects can have properties that are irreducible to the sum of the properties of their parts. But then, what is the point of positing consciousness at the level of basic particles as part of an explanation of how animals and human beings are conscious? Why not instead merely take the consciousness that exists at the level of an organism as a whole to be one of those properties irreducible to the sum of the organism’s parts? That is exactly what the traditional Aristotelian position does.

Goff says that there must be something that fleshes out the abstract structure described by physics, and alleges that “there doesn’t seem to be a candidate for being the intrinsic nature of matter other than consciousness” (Galileo’s Error, p. 133). But in fact there is no great mystery here in need of some exotic solution. We need only to see what is in front of our nose, which, as Orwell famously said, requires a constant struggle. The concrete reality that fleshes out the abstract structure described by physics is nothing other than the world of ordinary objects revealed to us in everyday experience. Physics is an abstraction from that, just as the representation of a person’s face in a pen and ink sketch is an abstraction from all the rich concrete detail to be found in the actual, flesh-and-blood face. No one thinks that the existence of pen and ink drawings raises some deep metaphysical puzzle about what fleshes out the two-dimensional black-and-white representation, and neither is there any deep metaphysical mystery about what fleshes out the abstract structure described by physics. The bizarre panpsychist solution is no more called for in the latter case than in the former.

Does that mean there is nothing more to be said about the intrinsic nature of matter beyond what common sense would say about it? Not at all, and Aristotelianism provides a detailed account what more there is to be said about it. It is to be found in the hylemorphist analysis of material substances as compounds of substantial form and prime matter, possessing causal powers and teleology, and so on. Again, for the details see Aristotle’s Revenge (as well as its predecessor Scholastic Metaphysics, and the work of other contemporary Aristotelians like David Oderberg). Goff is right that a radical solution is needed to the problems opened up by Galileo’s error. But it is to be found, not in panpsychism (which ultimately amounts to yet a further riff on Galileo’s error), but in a return to the classical philosophical wisdom that the early moderns abandoned.

Related posts:

The hollow universe of modern physics

June 27, 2022

Aristotle on the middle class

On CNN the other day, liberal commentator Van Jones complained that the Democrats are “becoming a party of the very high and the very low” ends of the economic spectrum, and do not appeal to those in the vast middle, including the working class. He notes that the “very well-educated and very well-off” segment of the party talks in a way that sounds “bizarre” to ordinary people, citing as examples the use of terms like “Latinx” and “BIPOC.” He could easily have added others, such as “cisgender,” “whiteness,” “intersectionality,” “heteronormativity,” “the carceral state,” and on and on. To the average person, the commentators and activists who use such jargon – insistently, humorlessly, and as if everyone does or ought to agree – sound like cult members in need of deprogramming, and certainly of electoral defeat. (I would also note that having a college degree and being facile with trendy political theory does not suffice to make one “very well-educated,” but let that pass.)