Edward Feser's Blog, page 21

September 18, 2022

Chomsky on consciousness

On the podcast Mind Chat, philosophers Philip Goff and Keith Frankish discuss the philosophical problem of consciousness with Noam Chomsky. Goff is a proponent of panpsychism and Frankish of illusionism, where Goff characterizes these, respectively, as the view that consciousness is everywhere and the view that consciousness is nowhere. (This might be a bit of an overstatement in the case of Frankish’s position, given what he says during the podcast.) Chomsky’s own position is not easy to capture in a simple label, but I think that it can, to a first approximation, be described as a kind of modest naturalism. The discussion is very interesting, and what follows is a summary with some comments of my own.

Many readers will recall that I had a recent exchange with Goff myself (here, here, and here). The issues and arguments that arose there are highly relevant to the discussion with Chomsky and my comments on it below.

Pseudo-questions

Where the study of consciousness is concerned, recent philosophy of mind has followed David Chalmers in distinguishing between “easy problems” and the “hard problem.” Identifying the neural correlates of various kinds of conscious awareness would be examples of an easy problem. By characterizing such a problem as “easy,” Chalmers doesn’t mean that it is trivial, or even easy in every respect. He just means that it is the sort of problem the solution to which seems clearly attainable using existing methods and standard scientific and philosophical assumptions. The “hard problem” is explaining why any of the neural processes in question are associated with conscious awareness, given that it seems at least prima facie possible that they could do what neuroscience describes them as doing in the complete absence of consciousness. (This is alleged to be shown by arguments like Chalmers’ “zombie argument,” along with other influential arguments like Frank Jackson’s “knowledge argument” and Thomas Nagel’s argument in his famous article “What is it Like to Be a Bat?”)

Chomsky is well-known for arguing that there are some things we may never be able to explain because evolution has molded our minds in such a way that they fall outside the range of our cognitive powers. This view has come to be known as “mysterianism,” and some philosophers, such as Colin McGinn, have applied it to the hard problem of consciousness, arguing that solving it is probably beyond our cognitive capacities.

Interestingly, Chomsky himself does not take that view. Indeed, in his exchange with Goff and Frankish, he suggests that the so-called hard problem is really a pseudo-problem. He points out that the fact that we can form an interrogative sentence does not by itself entail that it expresses a genuine question. With some interrogatives, there may be no possible way to answer them, and in that case, he says, we’re not dealing with a genuine question.

To illustrate this general point, he offers as an example the interrogative sentence “Why do things happen?” There is, he says, no possible answer to this, and so it is not a genuine question. Now, I don’t think this is actually a good example, because it seems to me that there is a plausible interpretation of this interrogative sentence on which it amounts to a real question susceptible of an answer. For example, it might be interpreted as asking why the world is such that change occurs in it, rather than being static in the way Parmenides and Zeno took it to be. And an answer would be Aristotle’s view that substances have potentialities as well as actualities, and that change occurs because these potentials are sometimes actualized.

Perhaps Chomsky would take all of this too to be suspect, but it would be better to have a less tendentious example to illustrate his general point. And that’s not hard to find. We could, altering another example famously given by Chomsky, consider the interrogative sentence “Why do colorless green ideas sleep furiously?” That clearly is something to which there is no possible answer, and it suffices to support Chomsky’s point that not every interrogative corresponds to a genuine question.

Now, Chomsky proposes that though a sentence like “What was it like to see the sunset last night?” asks a genuine question, the sentence “What is it like to see a sunset?” does not. Similarly, he says, “What is it like to see this red spot?” is a real question, but “What is it like to see red?” is not. There are, he says, ways we might go about explaining what seeing last night’s sunset was like or what seeing this red spot is like. By contrast, he claims, there is no way to go about answering questions about what it is like to see a sunset full stop, or what it is like to see red full stop. Hence these are pseudo-questions.

Yet these pseudo-questions seem, to Chomsky, to be the kinds that the discussion of the so-called hard problem focuses on. He doesn’t mention Nagel, but he seems clearly to have in mind questions like “What is it like to be a bat?” and the idea that neuroscientific research and the like cannot answer it. The reason there is such difficulty answering it, Chomsky thinks, is that interrogative sentences like these don’t convey genuine questions. What are labeled “easy questions” and “hard questions” concerning consciousness pretty much correspond, in Chomsky’s view, to genuine questions and pseudo-questions.

Now, I sympathize with Chomsky’s view that the so-called hard problem of consciousness is a pseudo-problem. As I said in my exchange with Goff, I would say that the problem arises only if we follow Galileo and his early modern successors in holding that color, odor, sound, heat, cold, and other “secondary qualities” do not really exist in matter in the way common sense supposes them to, but instead exist only in the mind (as the qualia of conscious experience) and are projected by us onto external reality. If you take this position, you are stuck with a conception of matter that makes it impossible to regard consciousness as material. The solution, I would say, is simply not to go along with this assumption in the first place, but to return to the Aristotelian-Scholastic view the early moderns reacted against, and which is compatible with the commonsense view of matter. The so-called hard problem of consciousness then dissolves. As Chomsky’s remarks later in the discussion make clear, he would be sympathetic with part of this story (though not, I’m sure, with the neo-Aristotelian bit).

It doesn’t seem to me, though, that Chomsky’s specific way of making the point about pseudo-questions is likely to convince someone who doesn’t already agree that the so-called “hard problem” is a pseudo-problem. The reason is that questions like “What is it like to see a sunset?,” and “What is it like to see red?” seem to me interpretable in ways that aresusceptible of an answer. For example, if you had never seen the color red, you might naturally ask precisely a question like the second one. And if someone then showed you a red object, you would surely think that your question had been answered. Or, if someone said “Well, it’s sort of like seeing dark orange, though not quite. But very different from seeing pale blue,” then you might judge this answer to be at least somewhat illuminating.

I imagine that Chomsky would respond that this misses his point, and that what he is criticizing is rather an interpretation of the interrogative sentences in question that would not be open to answering in ways like those I’ve described. That’s fair enough, but then it seems to me that the examples don’t really do the work he needs them to do. He would need to develop a more metaphysically substantive point about the problematic nature of the notion of qualia. But then this metaphysical pointwould be doing the work, and the simple linguisticway of making it that he resorts to at the beginning of the discussion would drop out as otiose.

Conscious and unconscious

The point about pseudo-questions, Chomsky says, is one of the sources of his reservations about the recent literature on the so-called hard problem of consciousness. It is one reason why, though he does think there are genuine mysteries that we are unable to solve, he isn’t convinced that the nature of consciousness is one of them.

Another problem he has with the recent literature, he says, is that he thinks that conscious and unconscious mental phenomena are so deeply intermingled that he doubts that we can extract the former out and still be left with a coherent picture. He gives the example of uttering a certain sentence in the course of a conversation. Obviously a person who does this is conscious, but the decision to utter the sentence is not itself conscious in the same way that, say, a runner might consciously decide to start running when he hears the starting pistol. (The example is mine, not Chomsky’s.) The runner might have the explicit thought “Time to go!” but the speaker doesn’t think “Time to utter this sentence.” He just does it.

This is indeed a very important point, and Chomsky notes that it fits in with his well-known work in linguistics, which posits unconscious mechanisms and rules that underlie linguistic competence. But in my view it is a point that has been developed in a more penetrating way by thinkers in the phenomenological tradition (such as Heidegger and Merleau-Ponty) than by the broadly functionalist or computationalist approach in analytic philosophy of mind that Chomsky’s work is closer to.

Indeed, as Hubert Dreyfus has argued (under the influence of this phenomenological tradition) it is a mistake to think of the unconscious on the model of rules (such as Chomskian rules of universal grammar). For rules always have an explicit content that must be understood before one can apply them. And to appeal to further rules in order to determine the interpretation of the first set just raises the problem again at a higher level, which threatens a vicious regress. (See e.g. the discussion of rule-following beginning at p. 174 of Dreyfus’s book What Computers Still Can’t Do.)

Moreover, Dreyfus points out, this computationalist model is an inheritance from the post-Cartesian approach to scientific explanation, according to which explaining a physical event involves identifying the laws by which it follows of necessity from antecedent events, in a manner that might be modeled by a machine. But this mechanistic model only works when we abstract out of it anything that smacks of the psychological – consciousness, intentionality, and so on. (This is precisely why Descartes had to relocate consciousness out of the material world and in a separate res cogitans, as Chomsky himself emphasizes later in the discussion with Goff and Frankish.) Hence an approach that appeals to computational rules, given its essentially mechanistic character, precisely leaves out what is distinctive of the mental, and thus cannot coherently claim to account for the mental.

Ghosts and machines

This brings us to some further important points raised by Chomsky concerning the origins of the modern mind-body problem. Gilbert Ryle famously characterized Descartes’ dualism as the theory of the “ghost in the machine.” It is often supposed that modern philosophy and science after Descartes preserved his mechanical model of matter while getting rid of the “ghost” of the Cartesian mind. But as Goff points out, Chomsky’s view is that the truth is closer to the opposite of this, and in particular that with Newton, modern thought essentially “exorcised the machine while leaving the ghost intact.”

What does Chomsky mean by this? He notes that the mechanical conception of nature that was put at the center of modern science and philosophy by Galileo and his successors conceived of matter on the model of machines. The idea was that the various phenomena studied by the sciences (solar systems, organisms, or whatever) could be understood as operating according to the same principles as mechanical artifacts (watches and the like being a favorite paradigm). This approach to explanation was adopted by all the major early modern thinkers.

But Descartes held, correctly in Chomsky’s view, that certain aspects of the human mind could not be accounted for on this mechanical model. For this reason he posited a separate principle to account for them, the res cogitans or thinking substance, and Chomsky takes this to be a perfectly ordinary sort of move to make in scientific investigation. (Not that Chomsky agrees with Descartes. He is merely objecting to those who represent Descartes’ positing of the res cogitans as if it were suspect from a scientific point of view or otherwise intellectually disreputable.)

Now, with Newton, Chomsky notes, modern physics abandoned a strictly mechanical model. What he means is that the early mechanists thought that the simple push-pull kind of causation that one sees in watches and the like could provide a model for how the physical world in general works, but Newton posited forces that did not operate in this way, and indeed the operation of which he did not explain or claim to explain at all. Gravitation seemed as “occult” as anything the medieval Aristotelians talked about. Newton’s work was nevertheless accepted because of the tremendous predictive success afforded by its mathematical representation of nature. Newtonian physics did not truly explain the phenomena with which it dealt, but carried the day because it describedthem so well.

In the history of physics after Newton, Chomsky says, the prevailing attitude came to be that anything was acceptable if it could be given a precise mathematical expression. The predictive success of such mathematical theories is what mattered, and the metaphysical question about explaining why things worked in the way the mathematics described receded into the background. For practical purposes, “matter” came to be treated as just whatever accepted physical theories happen to say about it. But, Chomsky notes, as early twentieth-century thinkers like Bertrand Russell and Arthur Eddington pointed out, physical theory actually tells us very little about what matter is actually like. It gives us only mathematical structure and is silent about what fleshes out that structure.

In this way, the early moderns’ clear and concrete conception of the natural world as susceptible of an exhaustive description on the model of a machine or mechanical artifact has been abandoned. In its place we have a highly abstract mathematical description of nature that tells us very little about its intrinsic nature. But at the same time, the Cartesian idea of the mind as the repository of qualities that cannot be given a mechanical or mathematical analysis remains. Hence, Chomsky concludes, what contemporary philosophy and science are left with is the “ghost” but without the “machine” – the reverse of the standard assumption, after Ryle, that modern science leaves us with the machine and has exorcised the ghost.

This is a longstanding theme in Chomsky’s work, which I’ve discussed before. As my longtime readers know, I am entirely sympathetic to it, and regard it as the key to understanding the intractability of the mind-body problem. The mechanical-cum-mathematical model of nature presupposed by modern materialism itself generates the hard problem of consciousness. Materialism thus cannot in principle solve that problem. Thinkers like Nagel have been making this point for decades, and are often wrongly thought to be carrying water for some variation on Cartesian dualism. But as Chomsky’s example shows, by no means does one have to be any kind of dualist to see the point.

Panpsychism and illusionism

Now, Russell argued that what we know best is consciousness itself, and that everything else we know, including physics, is derivative from this. He also held, again, that physics tells us about the abstract mathematical structure of matter, but not about its intrinsic nature. But if we suppose that consciousness is identical to properties of the brain, then it would follow that introspection gives us knowledge about the intrinsic nature of at least one material object, namely the brain itself. And this might give us a basis for extrapolating about the intrinsic nature of the material world in general.

Russell himself did not take this in a panpsychist direction, but later thinkers, such as Galen Strawson and Goff, have done so. Goff argues for panpsychism by way of an appeal to simplicity or parsimony. I have explained, in my exchange with Goff linked to above, why I think this argument fails.

Chomsky’s own criticism of Goff is that he thinks that panpsychism does not in fact sit well with the whole range of empirical evidence. In particular, he says that when we take account of the neural phenomena associated with conscious experience, we have reason to conclude that while human beings are conscious, tables, say (which have nothing like the complexity of our nervous systems), are not. There are also intermediate cases, such as fish, where it is not entirely clear what we should say. But what we don’t have is any basis for concluding that consciousness exists all across nature, from human beings to ordinary inanimate objects to fundamental particles. (Goff, as I noted in my exchange with him, is massively overgeneralizing from a handful of cases.)

Goff replies by saying that this objection of Chomsky’s presupposes that we know more about matter than one would otherwise expect Chomsky to think we do, given his endorsement of Russell’s and Eddington’s point about how little physics tells us. But Chomsky responds by noting that Goff overstates things when he suggests that science tells us nothing about the nature of matter. It doesn’t tell us nothing, just much less than many people suppose. And we can have evidence for thinking that some theories tell us more about it than others do. In particular, Chomsky repeats, neuroscience gives us grounds for concluding that while we are conscious, tables and the like are not.

Here too, I am completely sympathetic with Chomsky. What I would add can be found, in part, in my exchange with Goff linked to above. I would also direct the interested reader to my detailed discussion of Russell’s and Eddington’s structural realism in chapter 3 of Aristotle’s Revenge, especially at pp. 158-94. The view is susceptible of a variety of interpretations, and it is too simple to say flatly that physics tells us nothing about the nature of matter.

Chomsky also engages with Frankish’s illusionism. Frankish is skeptical of the idea that, in addition to one’s awareness of (say) the taste of the coffee he is drinking, he is aware via introspection of some inner and radically private quale of the taste of the coffee. The reality is that, in consciousness, we are aware of features of the world and of our reactions to them. We are not, over and above that, aware of some inner Cartesian realm of qualia.

Chomsky’s response is that he is partially sympathetic to this, but that he would be opposed to throwing out of the picture the psychological reactions we have to the world that people have in mind when they talk about consciousness. He thinks that the fact that these are genuine phenomena is evidenced by our ability to theorize about them. (He says that Nelson Goodman’s book The Structure of Appearance is a good example of how one can develop a substantive analysis of the way things seem to us in conscious awareness, whether or not Goodman’s account is ultimately successful.) Chomsky is also sympathetic to Russell’s view that consciousness is in fact what we know best.

Frankish replies by suggesting that the neural processes underlying introspection can distort things just as much as those underlying perception do. But as Chomsky goes on to point out, while what consciousness tells us about this or that object or event is certainly fallible, it doesn’t follow that the reality of consciousness itself is an illusion. (Here’s an analogy – mine, not Chomsky’s. Suppose I find that a certain person, Fred, is a chronic liar. This gives me good reason to doubt the things Fred tells me. But it hardly by itself gives me any reason to think that Fred himself doesn’t exist.)

It might seem that, as with Goff, Chomsky thinks that Frankish takes too far an insight that they have in common. But Frankish suggests that in fact he and Chomsky are basically in agreement apart from some terminological issues. In any case, here too I am sympathetic with Chomsky’s remarks, though I imagine that I have a more conservative view than he and Frankish do about how far science might revise our commonsense perceptual representation of the world. (The interested reader is directed to what I have to say about the primary versus secondary quality distinction at pp. 340-51 of Aristotle’s Revenge; about representationalist theories of perception at pp. 106-13; and about neuroscientific evidence vis-à-vis introspection and perception at pp. 442-56.)

Politics and economics

Goff’s and Frankish’s conversation with Chomsky ends with a brief discussion of matters of politics and economics. Chomsky says that the excesses of 1920s capitalism were corrected to some extent beginning in the 30s, leading eventually to a somewhat more humane form of capitalism by the 50s and 60s. Then, he thinks, Reagan and Thatcher turned the world back in the direction of something like the 1920s kind of capitalism. But, he suggests, something like the reforms that partially corrected that kind of capitalism might occur again.

Chomsky’s description is highly tendentious, which is not to say that I disagree with everything about it. But his discussion is too brief, and the issues too complicated, for it to be worthwhile commenting further here. I’ll simply direct the interested reader, first, to this post on my own views about the pluses and minuses of capitalism; and second, to this relatively recent post about Chomsky’s politics.

Related posts:

Chomsky on the mind-body problem

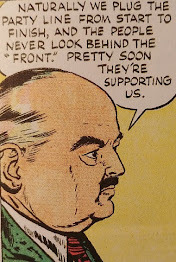

Chomsky’s “propaganda model” of mass media

Problems for Goff’s panpsychism

The hollow universe of modern physics

Reading Rosenberg, Part VIII [on neuroscience and the reliability of introspection]

September 12, 2022

Perfect world disorder (sans paywall)

September 9, 2022

Talking about All One in Christ

Some recent interviews about my book

All One in Christ: A Catholic Critique of Racism and Critical Race Theory

: A print interview conducted by Carl Olson appears today at Catholic World Report. A few days ago I did a radio interview about the book for The Drew Mariani Show. And the book was one of the topics covered in my recent interview for Thomas Mirus’s Catholic Culture podcast.

Some recent interviews about my book

All One in Christ: A Catholic Critique of Racism and Critical Race Theory

: A print interview conducted by Carl Olson appears today at Catholic World Report. A few days ago I did a radio interview about the book for The Drew Mariani Show. And the book was one of the topics covered in my recent interview for Thomas Mirus’s Catholic Culture podcast.

September 6, 2022

Perfect world disorder

My essay “Perfect World Disorder” appears today at The Postliberal Order. You can read it here (though a subscription is required in order to read the whole thing). Good time to subscribe!

September 5, 2022

Libertarianism, jazz, and Critical Race Theory

I was recently interviewed by Thomas Mirus for the Catholic Culture podcast. The discussion was pretty wide ranging, covering topics as diverse as libertarianism, the aesthetics of the music of Thelonious Monk, and Critical Race Theory. You can watch the interview at YouTube or at the Catholic Culture website.

I was recently interviewed by Thomas Mirus for the Catholic Culture podcast. The discussion was pretty wide ranging, covering topics as diverse as libertarianism, the aesthetics of the music of Thelonious Monk, and Critical Race Theory. You can watch the interview at YouTube or at the Catholic Culture website.

September 2, 2022

Individualism and socialism versus the family

Here’s another unpublished lecture the text of which I’ve posted at my main website. The title is “Socialism versus the Family,” and I presented it at the Heritage Foundation back in February of 2019. The talk begins by explaining the economics and ethos of socialism, and how socialism is related to liberalism. It then explains the nature of the family, emphasizing the features recognized by natural law theorists and evolutionary psychology alike. Finally it shows how egalitarian socialism is inherently incompatible with the family, but also how the liberal individualism embraced by too many modern conservatives is precisely what paved the way for the egalitarian assault on the family. You can watch the video of the lecture here.

Here’s another unpublished lecture the text of which I’ve posted at my main website. The title is “Socialism versus the Family,” and I presented it at the Heritage Foundation back in February of 2019. The talk begins by explaining the economics and ethos of socialism, and how socialism is related to liberalism. It then explains the nature of the family, emphasizing the features recognized by natural law theorists and evolutionary psychology alike. Finally it shows how egalitarian socialism is inherently incompatible with the family, but also how the liberal individualism embraced by too many modern conservatives is precisely what paved the way for the egalitarian assault on the family. You can watch the video of the lecture here.

August 26, 2022

What is classical theism?

My essay “What is Classical Theism?” is among those that appear in the volume

Classical Theism: New Essays on the Metaphysics of God

, edited by Jonathan Fuqua and Robert C. Koons and forthcoming from Routledge. Follow the link to check out its excellent roster of contributors and range of topics.

My essay “What is Classical Theism?” is among those that appear in the volume

Classical Theism: New Essays on the Metaphysics of God

, edited by Jonathan Fuqua and Robert C. Koons and forthcoming from Routledge. Follow the link to check out its excellent roster of contributors and range of topics.

Plato on democracy and tyranny

Over at Twitter, I posted a long thread of passages from Plato’s

Republic

setting out his account of how a democratic society’s fixation on liberty and equality yields the tyrannical soul. You can read the thread here. The relevance to the current situation in the West will be obvious, but it is a theme I explored in an American Mind article from a couple of years ago.

Over at Twitter, I posted a long thread of passages from Plato’s

Republic

setting out his account of how a democratic society’s fixation on liberty and equality yields the tyrannical soul. You can read the thread here. The relevance to the current situation in the West will be obvious, but it is a theme I explored in an American Mind article from a couple of years ago.

August 21, 2022

Countering disinformation about Critical Race Theory

Critical Race Theory (CRT) has over the last two years been a topic of enormous controversy. But what is it, exactly? Chapter 4 of my book

All One in Christ: A Catholic Critique of Racism and Critical Race Theory

is devoted to answering that question at length. I go on in chapters 5, 6, and 7 to spell out the many philosophical, social scientific, and theological problems with the view. (As this breadth of issues indicates, there is much in the book that will be of interest and value to non-Catholics.) But chapter 4 is entirely expository, and quotes extensively from CRT writers themselves, so that there can be no mistake about how extreme and dangerous are the views that the subsequent chapters go on to criticize.

Critical Race Theory (CRT) has over the last two years been a topic of enormous controversy. But what is it, exactly? Chapter 4 of my book

All One in Christ: A Catholic Critique of Racism and Critical Race Theory

is devoted to answering that question at length. I go on in chapters 5, 6, and 7 to spell out the many philosophical, social scientific, and theological problems with the view. (As this breadth of issues indicates, there is much in the book that will be of interest and value to non-Catholics.) But chapter 4 is entirely expository, and quotes extensively from CRT writers themselves, so that there can be no mistake about how extreme and dangerous are the views that the subsequent chapters go on to criticize. Some advocates of CRT have responded to the exposure of its extremism with what can fairly be described as a program of disinformation. We are told that CRT is merely an abstruse legal theory of little interest to anyone outside the university, and certainly irrelevant to anything being taught to children; or that insofar as it does have influence outside the academy, it is concerned with nothing more than teaching about the history of racism; or that in any event it has nothing to do with the ideas peddled in bestsellers like Ibram X. Kendi’s How to Be an Antiracist or Robin DiAngelos’s White Fragility. These claims are so easily refuted that it is hard not to see in them a cynical tactic of deliberate obfuscation.

Is CRT just an abstract legal theory?

Start with the first claim, about the nature and influence of CRT. Law professors Richard Delgado and Jean Stefancic are not only critical race theorists themselves, but the authors of Critical Race Theory: An Introduction, a well-known primer on the subject. They write:

Although CRT began as a movement in the law, it has rapidly spread beyond that discipline. Today, many scholars in the field of education consider themselves critical race theorists who use CRT’s ideas to understand issues of school discipline and hierarchy, tracking, affirmative action, high-stakes testing, controversies over curriculum and history, bilingual and multilingual education, and alternative and charter schools. (p. 7)

They then go on to cite “political scientists,” “women’s studies professors,” “ethnic studies,” “American studies,” “philosophers,” “sociologists, theologians, and health care specialists” as among the scholars, professionals, and fields influenced by, and applying ideas drawn from, CRT (pp. 7-8). Similarly, law professor Angela Harris’s foreword to Delgado and Stefancic’s book notes that:

Critical race theory has exploded from a narrow sub-specialty of jurisprudence chiefly of interest to academic lawyers into a literature read in departments of education, cultural studies, English, sociology, comparative literature, political science, history, and anthropology around the country. (p. xvi)

Delgado and Stefancic also note that though CRT began as a movement in the law, the influences on its development extend well beyond that field, and include “radical feminism,” the Marxist thinker Antonio Gramsci, and the postmodernists Michel Foucault and Jacques Derrida (p. 5). And they emphasize that “unlike some academic disciplines, critical race theory contains an activist dimension. It tries not only to understand our social situation but to change it” and indeed “transform it” (p. 8). They cite the push for “reconstructing the criminal justice system” and the “‘Black Lives Matter’ movement” as among the practical applications of ideas associated with CRT (p. 124).

Another representative CRT work is the anthology Critical Race Theory: The Key Writings that Formed the Movement, edited by Kimberlé Crenshaw, Neil Gotanda, Gary Peller, and Kendall Thomas. In their introduction to the volume, they note that the Critical Legal Studies movement “organized by a collection of neo-Marxist intellectuals, former New Left activists, ex-counter-culturalists” and the like “played a central role in the genesis of Critical Race Theory” (p. xvii). They write that:

By legitimizing the use of race as a theoretical fulcrum and focus in legal scholarship, so-called racialist accounts of racism and the law grounded the subsequent development of Critical Race Theory in much the same way that Marxism’s introduction of class structure and struggle into classical political economy grounded subsequent critiques of hierarchy and social power. (p. xxv)

And in another obvious echo of Marxism, they emphasize that CRT is an activist movement devoted to “liberation,” whose theorists “desire not merely to understand the vexed bond between law and racial power but to change it” (p. xiii).

Hence, when CRT’s critics portray it as far more than a mere academic legal theory and indeed as a wide-ranging revolutionary political program with Marxist and postmodernist influences, which has swept through academia and seeks radically to transform society through the educational and criminal justice systems, they are not manufacturing a bogeyman. They are simply repeating what CRT advocates themselves have explicitly said.

Is CRT merely about teaching history?

Again, another claim often made is that to the extent that CRT has any influence in schools and other contexts outside the university, it is concerned merely with teaching about the history of racism. When people uninformed about CRT hear this, they are likely to think that what it involves is teaching about slavery in the American south, Jim Crow laws, the Ku Klux Klan, and so on. But that is far from the truth. These are examples of what Delgado and Stefancic label “outright racism,” and as they emphasize, this is to be sharply distinguished from the far more subtle “white privilege” that CRT claims to identify and seeks to extirpate (p. 90).

This purported “white privilege” is sosubtle that even if “outright racism” of the familiar sorts is entirely eliminated, white privilege would allegedly remain “intact” so that the “system of white over black/brown will remain virtually unchanged” and “we remain roughly as we were before” (p. 91). This unnoticed racism is nevertheless claimed to be “ordinary, not aberrational… the usual way society does business” (p. 8) and indeed is “pervasive, systemic, and deeply ingrained” to such an extent that “no white member of society seems quite so innocent” (p. 91). The purported “white privilege” of these members of society involves a “myriad of social advantages, benefits, and courtesies that come with being a member of the dominant race” (p. 89). The hostility of whites against non-whites is claimed to manifest itself in “implicit bias” or negative attitudes that are so elusive that whites are unconscious of harboring them (p. 143-44), and in “microaggressions” or racist acts so subtle that whites are unaware they are committing them.

Racism is held by CRT to be so “embedded in our thought processes and social structures” that it is not only conservatism that CRT opposes, but liberalism too (p. 26-27). Like Marxism, CRT stakes out a position far to the left of traditional Democratic Party politics. In place of liberalism’s commitment to “color blindness and neutral principles of constitutional law,” CRT writers advocate “aggressive, color-conscious efforts to change the way things are” (ibid.). CRT calls for “programs that assure equality of results,” even if this conflicts with liberalism’s emphasis on the “moral and legal rights” of the individual (p. 29). One CRT proposal, report Delgado and Stefancic, would be to have “admissions officers discount, or penalize, the scores of candidates” of a “white, suburban” background because of their “white privilege” (p. 134). Some CRT writers even wonder whether “whites [should] be welcome in the movement and at its workshops and conferences” (p. 105). Indeed, a central theme of CRT is the malign influence of “whiteness” itself, a “quality pertaining to Euro-American or Caucasian people or traditions” (p. 186). “Critical White Studies,” Delgado and Stefancic tell us, is a subfield of CRT devoted to “the study of the white race,” which has “put whiteness under the lens” (p. 85).

In place of liberalism’s traditional emphasis on freedom of expression, some CRT writers call for “campus speech codes” and “tort remedies for racist speech” (p. 25), or even the “criminalization” of such speech (p. 125) – which, given the amorphous notions of “implicit bias” and “microaggressions,” could cover anything a CRT advocate finds objectionable. At the same time, in light of the systemic racism they claim afflicts criminal justice, CRT writers advocate lighter sentences or even “jury nullification” for offenses “such as shoplifting or possession of a small amount of drugs” (pp. 122-23). Delgado and Stefancic blandly note that one CRT writer proposes that “the values of hip-hop music and culture could serve as a basis for reconstructing the criminal justice system” (p. 124).

CRT also rejects “traditional civil rights discourse, which stresses incrementalism and step-by-step progress” and instead “questions the very foundations of the liberal order” including ideas such as “equality theory, legal reasoning, Enlightenment rationalism,” and “equal treatment for all persons, regardless of their different histories or current situations” (pp. 3 and 26). Accordingly, CRT holds that the change it advocates may have to be “convulsive and cataclysmic” rather than involving a “peaceful transition,” and “if so, critical theorists and activists will need to provide criminal defense for resistance movements and activists and to articulate theories and strategies for that resistance” (pp. 154-55).

This is just the tip of the iceberg, for according to the CRT notion of “intersectionality,” many individuals “experience multiple forms of oppression” involving not just race but “sex, class, national origin, and sexual orientation” (pp. 58-59). Hence the CRT analysis of and remedies for “systemic racism” must be applied to an analysis of and extirpation of these other alleged forms of oppression as well.

Here I have been quoting from just a single representative text, for purposes of illustration. As the reader of All One in Christ will discover, other CRT writers have other, even more extreme things to say. Whatever one thinks of these ideas, they give the lie to the claim that CRT is merely about teaching the history of racism. It is about promoting a sweeping, revolutionary social and political ideology that even many liberals and Democratic voters would find disturbing if they knew about it.

Kendi, DiAngelo, and CRT

The books by Kendi and DiAngelo mentioned above are by far the most influential works promoting the ideas of CRT. Yet some have claimed that their work has nothing to do with Critical Race Theory. This claim too is easily refuted. Kendi himself has acknowledged the influence of CRT on his work:

I’ve certainly been inspired by critical race theory and critical race theorists. The ways in which I’ve formulated definitions of racism and racist and anti-racism and anti-racist have not only been based on historical evidence, but also Kimberlé Crenshaw’s intersectional theory. She’s one of the founding and pioneering critical race theorists who in the late 1980s and early 1990s said, “You know what? Black women aren’t just facing racism, they’re not just facing sexism, they’re facing the intersection of racism and sexism.” It’s important for us to understand that and that’s foundational to my work.

To be sure, in another context, Kendi has said:

I admire critical race theory, but I don’t identify as a critical race theorist. I’m not a legal scholar. So I wasn’t trained on critical race theory. I’m a historian... I didn’t attend law school, which is where critical race theory is taught.

But there are two problems with this. First, what matters is whether Kendi is promoting ideas derived from CRT, not whether he is himself a “critical race theorist” in the narrow sense of a legal scholar of a certain kind. And again, he himself has admitted that his work is “inspired” by CRT, indeed that one brand of CRT is “foundational” to his work. Second, as we have seen, CRT writers like Harris, Delgado, and Stefancic admit that CRT is not confined to legal scholarship but has extended far into other parts of the academy, including history, Kendi’s field. So it is disingenuous for him to pretend that the fact that he didn’t go to law school shows that he can’t count as a critical race theorist. If you go just by the actual content of his books and compare it to what is said in works that everyone acknowledges to be works of CRT, it is obvious that he is a critical race theorist.

The same thing goes for DiAngelo. Her academic field is education rather than law, but Delgado and Stefancic themselves put special emphasis on education as a field on which CRT has had dramatic influence. So it would be quite silly to pretend that the fact that she, like Kendi, is not a law professor somehow suffices to show that she is not a critical race theorist. More importantly, she is manifestly a promoter of ideas drawn from CRT, whether or not one wants to classify her as a “critical race theorist” in some narrow sense. The central ideas of White Fragility are the CRT themes of “systemic racism,” “white privilege,” the analysis and critique of “whiteness,” and the insufficiently radical nature of liberalism. In her book Nice Racism, DiAngelo explicitly cites the prominent critical race theorists Kimberlé Crenshaw, Derrick Bell, and Cheryl Harris as among the influences on her work.

Some may nevertheless object that, even if it is admitted that Kendi and DiAngelo are promoters of CRT, it is inappropriate to put as much emphasis on their work as critics of CRT have, since their books are popularizations. But there are two problems with this objection. First, Kendi and DiAngelo are not mere popularizers, but academics in their own right. They can be presumed to know what they are talking about. Second, though some CRT adepts might wish that it was Derrick Bell’s or Kimberlé Crenshaw’s books rather than How to Be an Antiracist and White Fragility that became bestsellers, that is not what has happened. It is Kendi’s and DiAngelo’sbooks that have in fact had the widest readership and influence, and thus their presentation of CRT ideas that has molded public perception of the movement. It is only natural, then, for critics of CRT to give them a proportionate amount of attention in response.

As readers of my book All One in Christ will find, the content of CRT is even more disturbing than this brief summary indicates – and it is also riddled with blatant logical fallacies, crude social scientific errors, and assumptions and policy recommendations that are utterly contrary to the natural moral law and the Catholic faith. It is unsurprising that advocates of CRT would like to disguise its true nature, but also imperative that they not be allowed to do so.

August 15, 2022

Aquinas on St. Paul’s correction of St. Peter

A pope speaks ex cathedra when he presents some teaching in a formal and definitive manner that is intended infallibly to settle debate about it once and for all. This is an exercise of what is called the “extraordinary magisterium,” and Catholics are obligated to give such declarations their unreserved assent. The ordinary magisterium of the Church can also teach infallibly under certain circumstances (which I have discussed elsewhere), and here too such teaching is owed unreserved assent. Even when the pope or the Church teach about a matter of faith or morals in a manner that is not infallible, Catholics normally owe such teaching what is called “religious assent,” an adherence that is not absolute but nevertheless firm.

A pope speaks ex cathedra when he presents some teaching in a formal and definitive manner that is intended infallibly to settle debate about it once and for all. This is an exercise of what is called the “extraordinary magisterium,” and Catholics are obligated to give such declarations their unreserved assent. The ordinary magisterium of the Church can also teach infallibly under certain circumstances (which I have discussed elsewhere), and here too such teaching is owed unreserved assent. Even when the pope or the Church teach about a matter of faith or morals in a manner that is not infallible, Catholics normally owe such teaching what is called “religious assent,” an adherence that is not absolute but nevertheless firm. There can nevertheless be very rare exceptions where those learned in some matter of faith or morals who detect difficulties in a magisterial statement are permitted respectfully to raise objections to it and ask the Church for clarification. This was explicitly acknowledged in the instruction Donum Veritatis issued by Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger under Pope St. John Paul II. The clearest sort of case where this would be permitted would involve a magisterial statement that appears to conflict with the previous settled teaching of the Church, and Donum Veritatis explicitly distinguishes respectful criticism of the kind in question from “dissent” from the Church’s traditional teaching.

I have in another place discussed this matter in detail, and as I show there, the teaching of Donum Veritatis is by no means a novelty, but has deep roots in the tradition of the Church. Among the most important precedents is the teaching of St. Thomas Aquinas about St. Paul’s correction of St. Peter, and how that episode illustrates how Catholics can in rare cases have the right and even the duty to correct their prelates. I discussed Aquinas’s teaching in that earlier article, but here I want to examine it in greater detail.

The first thing to note is that Aquinas’s position in no way reflects a weaker conception of papal authority than the one that prevailed in later centuries. On the contrary, in the Summa Theologiae St. Thomas writes:

[T]he promulgation of a creed belongs to the authority of the one who has the authority to fix, in the form of sentences, the things that belong to the Faith (ea quae sunt fidei), so that they might be held by everyone with an unshakable faith.

Now this belongs to the authority of the Supreme Pontiff, “to whom,” as Decretals, dist. 17 says, “the greater and more difficult questions in the Church are referred.” Hence, in Luke 22:32 our Lord said to Peter, whom He set up as Supreme Pontiff, “I have prayed for you, Peter, that your faith might not fail; and when you have been converted, strengthen your brothers.”

And the reason for this is that the Faith ought to be one for the whole Church – this according to 1 Corinthians 1:10 (“... that you should all profess the same thing, and that there not be schisms among you”). But this condition could not be preserved unless a question about the Faith that arises from the Faith were determined by someone who presides over the whole Church in such a way that his decision (sententia) is held firmly by the whole Church.

And so the new promulgation of a creed belongs solely to the authority of the Supreme Pontiff, just like all the other things that pertain to the Church as a whole, such as convening a general council and other things of this sort. (Summa Theologiae II-II.1.10, Freddoso translation)

Note that Aquinas here characterizes the Supreme Pontiff or pope as having authority to settle doctrinal disputes in such a way that his decisions must be “held firmly” and indeed with “unshakable faith” by Catholics. And he describes Peter as Supreme Pontiff. Yet he also elsewhere goes on to approve of Paul’s correction of Peter, and to see in it an example for later Catholics to follow. How can both of these things be true? The answer, obviously, is that Aquinas, like the Church today, recognizes a distinction between ex cathedra papal teaching and papal teaching of a less definitive nature. And like the Church today, he recognizes that under certain circumstances, the latter can not only be in error but even open to criticism by the faithful.

What circumstances would those be? Let’s take a look at what Aquinas says. The relevant texts are to be found in Summa Theologiae II-II.33.4and in Aquinas’s Commentary on Saint Paul’s Letter to the Galatians, in Chapter 2, Lecture 3. The commentary discusses in some detail the famous incident when Paul publicly rebuked Peter. To give some context, here is how the Catholic Encyclopedia’s article on St. Peter summarizes what happened:

While Paul was dwelling in Antioch… St. Peter came thither and mingled freely with the non-Jewish Christians of the community, frequenting their houses and sharing their meals. But when the Christianized Jews arrived in Jerusalem, Peter, fearing lest these rigid observers of the Jewish ceremonial law should be scandalized thereat, and his influence with the Jewish Christians be imperiled, avoided thenceforth eating with the uncircumcised.

His conduct made a great impression on the other Jewish Christians at Antioch, so that even Barnabas, St. Paul's companion, now avoided eating with the Christianized pagans. As this action was entirely opposed to the principles and practice of Paul, and might lead to confusion among the converted pagans, this Apostle addressed a public reproach to St. Peter, because his conduct seemed to indicate a wish to compel the pagan converts to become Jews and accept circumcision and the Jewish law.

End quote. Note that though it was Peter’s actions rather than his words that caused the problem, the controversy was nevertheless doctrinal in nature. For it was “principles” as well as sound practice that Paul sought to uphold in the face of Peter’s bad example, and in particular he wished to prevent others from being led into the doctrinal error of supposing that “pagan converts [were obligated] to become Jews and accept circumcision and the Jewish law.”

This is exactly how Aquinas saw the situation. In the Galatians commentary, he says that what Peter had done posed “danger to the Gospel teaching,” and that Peter and those who followed his example “walked not uprightly unto the truth of the Gospel, because its truth was being undone” (emphasis added). Peter failed to do his duty insofar as “the truth must be preached openly and the opposite never condoned through fear of scandalizing others” (emphasis added). Clearly, then, in Aquinas’s view the problem was not merely that Peter acted badly, but that he seemed to condone doctrinal error and risked leading others to do the same.

A second point Aquinas makes in the Galatians commentary is that Paul rebuked Peter “openly,” “not in secret… but publicly.” And he says that “the manner of the rebuke was fitting, i.e. public and plain” because Peter’s “dissimulation posed a danger to all.”

A third point Aquinas makes here is that this rebuke nevertheless was not a matter of usurping Peter’s authority. Aquinas says that “the Apostle opposed Peter in the exerciseof authority, not in his authority of ruling” (emphasis added). For Aquinas, it’s not that Peter did not have papal authority, but rather that in this instance his exercise of it amounted to an abuse. What Paul was doing was reminding Peter to do his duty. In this way, says Aquinas, Paul “benefitted” Peter and “shows how he helped Peter by correcting him.”

Finally, Aquinas proposes the following as the lesson of this episode:

Therefore from the foregoing we have an example: prelates, indeed, an example of humility, that they not disdain corrections from those who are lower and subject to them; subjects have an example of zeal and freedom, that they fear not to correct their prelates, particularly if their crime is public and verges upon danger to the multitude.

End quote. Since the pope is a prelate, and the example involved no less than Peter, the first pope, it is obvious that Aquinas intends this lesson to apply to popes and not merely to lesser prelates.

In the Summa, Aquinas makes similar remarks, but also adds some crucial further points. The passage is worth quoting from at length:

[F]raternal correction is a work of mercy. Therefore even prelates ought to be corrected...

A subject is not competent to administer to his prelate the correction which is an act of justice through the coercive nature of punishment: but the fraternal correction which is an act of charity is within the competency of everyone in respect of any person towards whom he is bound by charity, provided there be something in that person which requires correction…

Since, however, a virtuous act needs to be moderated by due circumstances, it follows that when a subject corrects his prelate, he ought to do so in a becoming manner, not with impudence and harshness, but with gentleness and respect…

It would seem that a subject touches his prelate inordinately when he upbraids him with insolence, as also when he speaks ill of him...

To withstand anyone in public exceeds the mode of fraternal correction, and so Paul would not have withstood Peter then, unless he were in some way his equal as regards the defense of the faith. But one who is not an equal can reprove privately and respectfully… It must be observed, however, that if the faith were endangered, a subject ought to rebuke his prelate even publicly. Hence Paul, who was Peter's subject, rebuked him in public, on account of the imminent danger of scandal concerning faith, and, as the gloss of Augustine says on Galatians 2:11, “Peter gave an example to superiors, that if at any time they should happen to stray from the straight path, they should not disdain to be reproved by their subjects.”

To presume oneself to be simply better than one's prelate, would seem to savor of presumptuous pride; but there is no presumption in thinking oneself better in some respect, because, in this life, no man is without some fault. We must also remember that when a man reproves his prelate charitably, it does not follow that he thinks himself any better, but merely that he offers his help to one who, “being in the higher position among you, is therefore in greater danger,” as Augustine observes in his Rule quoted above.

End quote. Here too, Aquinas teaches that prelates can sometimes err in a way that threatens the faith; that when this occurs they can be corrected by their subjects; that this correction can take place publicly; that this is a matter of helping a prelate, and that the prelate should be open to accepting such help; and (since his example is once again Paul’s correction of Peter) that all of this applies even to popes. But he makes the further important point that it is wrong to object either that subjects who correct prelates thereby exceed their authority, or that such subjects are guilty of a sin of pride.

In response to the first objection, Aquinas says that what subjects lack is the right to carry out a certain kind of correction, namely the kind “which is an act of justice through the coercive nature of punishment.” In other words, a prelate who abuses his authority in the ways Aquinas has in view does not thereby losehis authority. His is still a prelate with all the authority that that entails, and the one who corrects him is still subject to him. Hence the subject cannot punish a prelate for his errors, remove him from office, or the like. But that does not entail that he cannot simply point out to the prelate that he is in error. There is no usurpation of authority in that, says Aquinas, but rather an “act of charity” of a “fraternal” nature. In response to the second objection, Aquinas points out that it is simply not the case that the correction of a prelate must be motivated by the sin of pride. It can instead be motivated by charity and a desire to help.

But this brings us to a further, and absolutely crucial, point added by the discussion in the Summa. Since a subject remains a subject, even his justifiable correction of a prelate must not be carried out with “insolence,” “impudence,” or “harshness,” but rather “in a becoming manner,” “charitably” and “with gentleness and respect.” And as Aquinas says in another place, it is irrelevant whether the prelate who needs correction is an evil man. For the office he holds belongs to Christ, and that office therefore deserves honor whether or not the man who holds it does.

Applied to the case of a pope, Aquinas’s teaching on the correction of prelates by their subjects can be summed up in the following points:

1. When a pope is not making an ex cathedradefinition, it is possible for him to fail to do his duty to uphold orthodox doctrine, even in a manner that seems to condone its opposite.

2. When this occurs, it is permissible for the faithful to correct him, and to do so publicly if his error is public and threatens to mislead many.

3. This is in no way a challenge to the pope’s authority or a manifestation of pride, but on the contrary constitutes charitable assistance to the pope in properly exercising his authority.

4. However, such correction must only ever be carried out in a humble and respectful manner, and never with insolence or harshness.

5. When such respectful criticism is offered, a pope should respond to it with humility.

As I noted in the article referred to above, Aquinas’s position is by no means unique in the tradition. Similar teaching is to be found in the writings of St. Robert Bellarmine, St. John Henry Newman, and other eminent theologians in Catholic history. St. Francis de Sales wrote:

Thus, we do not say that the Pope cannot err in his private opinions, as did John XXII, or be altogether a heretic, as perhaps Honorius was… When he errs in his private opinion he must be instructed, advised, convinced; as happened with John XXII… So everything the Pope says is not canon law or of legal obligation; he must mean to define and to lay down the law for the sheep, and he must keep the due order and form… And again we must not think that in everything and everywhere his judgment is infallible, but then only when he gives judgment on a matter of faith in questions necessary to the whole Church; for in particular cases which depend on human fact he can err, there is no doubt, though it is not for us to control him in these cases save with all reverence, submission, and discretion. (The Catholic Controversy, pp. 225-26)

Naturally, such statements raise further questions and call for qualifications of various kinds. Donum Veritatis addresses some of them, as do other statements made by Cardinal Ratzinger during John Paul II’s pontificate. Again, see the article referred to above. And again, as the teaching of Aquinas and the other saints and theologians cited here shows, Donum Veritatis does not add some novelty to the tradition, but builds on what was already long there.

Related posts:

The Church permits criticism of popes under certain circumstances

Popes, heresy, and papal heresy

Edward Feser's Blog

- Edward Feser's profile

- 329 followers