Edward Feser's Blog, page 27

December 2, 2021

Geach on original sin

Recently we dipped into Peter Geach’s book

Providence and Evil

. Let’s do so again, looking this time at what he has to say about the doctrine of original sin. Geach says that the doctrine holds that human beings have “inherited… [a] flawed nature,” and indeed that:

Recently we dipped into Peter Geach’s book

Providence and Evil

. Let’s do so again, looking this time at what he has to say about the doctrine of original sin. Geach says that the doctrine holds that human beings have “inherited… [a] flawed nature,” and indeed that: The traditional doctrine is that since the sin of our first parents, men have been conceived and born different in nature from what they would have been had our first parents stood firm under trial. As C. S. Lewis puts it, a new species, not made by God, sinned itself into existence. (pp. 89-90)

Needless to say, this is a very arresting way of putting things, but (as Geach would no doubt agree) it is hardly precise and it is potentially misleading. Human beings are (as we Thomists would say) by nature rational animals. What does it mean, then, to say that a “new species” existed after the sin of our first parents? Does that entail that they were rational animals by nature but we are not? Or that we are rational animals by nature but they were not? Neither of those things is true, so that it cannot literally be the case that a “new species” existed after the Fall. That remark is best understood as just a colorful way of saying that while we have the same nature that our first parents had prior to original sin (namely a human nature, the nature of a rational animal), there is now a flaw in that nature that did not then exist.

Flawed nature

So far so good. But what exactly does it mean to speak of a “flawed nature”? Consider a triangle, which is a closed plane figure with three straight sides. That is its nature; it is what makes it a thing of the kind it is. Suppose I draw a triangle, but badly, so that the sides are not perfectly straight. Have I somehow changed the nature of triangles? No. Does the particular triangle I have drawn have a “flawed nature”? It seems more correct to say that the triangle is flawed than that its nature is.

Similarly, if a dog suffers a serious permanent injury to one of its legs, it would not be correct to say that the dog has a different nature from a dog that has four healthy legs. They have the same nature – they would not both be dogs otherwise – but the injured dog does not manifest all the properties that would ordinarily flow from that nature (in the Scholastic sense of “properties”). But it would also be a bit odd to speak of the injured dog as having a “flawed nature.” Here too, it isn’t the nature that is flawed; rather, it is the individual that has the nature that is flawed.

Having said that, there is a loose sense in which you might say that such a dog has a flawed nature. After all, unless the deformation is somehow remedied, the dog will never again walk as well as a dog with four healthy legs can. It will develop an unusual gait, and this will become “second nature” to it. Indeed, it may get so used to walking and running in this unusual way that if you were suddenly to restore the injured leg to perfect health, the dog might be at least temporarily disoriented and still not be able to walk normally.

Now, we are all familiar from everyday experience with the way in which a habit of action can become “second nature.” This could involve something innocuous or even good, such as the ability to play a musical instrument or to speak a new language. You might get so good at such things that you are able to do them without thinking about it. It is as if they were part of your very nature, even though in fact they are not (since you still would have existed, and thus had the same nature, if you’d never acquired these abilities).

Of course, something that we do by “second nature” in this sense could also be bad, such as a neurotic habitual way of thinking, feeling, or acting, or a habitual sin. Such a habit or tendency would in an obvious sense be contrary to our nature, which is precisely why we judge it to be bad. For example, people sometimes have odd addictions, such as eating kitchen cleanser, which can damage the teeth and the lining of the throat. Obviously, people also often become addicted to drugs or to excessive alcohol use, with the familiar bad consequences. It is in one sense hardly natural to human beings to do these things, precisely because our nature makes it bad for us to do them. But these tendencies can nevertheless become so deeply habituated that they become something like a “second nature” superimposed on our nature and frustrating its fulfillment.

One way to interpret the notion of the “flawed nature” entailed by original sin, then, is as a “second nature” that is superimposed on and frustrates the fulfilment of human nature – but, in this case, a “second nature” that is in some sense inherited from our first parents rather than acquired after birth. (I add that this is not what Geach himself says, but rather one possible way of interpreting what Geach says.)

Bad will

In the case of original sin, Geach says, the defect in our nature concerns the will. He writes:

Will is not simply, and not primitively, a matter of choice. There is, presupposed to all choosing, a movement of the will towards some things that are wanted naturally; to live, to think, and the like, in short to be a man. If man were as he ought to be, there would be nothing wrong with this natural willing, voluntas ut natura as the scholastics called it. But if the nature a man has inherited is flawed, then a will that acquiesces in this flawed nature is perverse from the start; and from this perverse start actual wrong choices will certainly proceed, given time. (p. 90)

Go back to my analogy of natural versus acquired habits. Every normal human being has a natural inclination to drink water. You might say that the human will aims at doing so even before a particular conscious choice to drink it. Similarly, the person who has developed a strange addiction to eating kitchen cleanser thereby has, by “second nature” as it were, a will that is aimed at eating it, even before a particular conscious choice to eat it. The person’s will has to that extent been deformed.

Original sin, as Geach (as I am interpreting him) expounds it, can be seen as a matter of having in some sense inherited a “second nature” that aims one’s will at the wrong things, even before one makes particular conscious choices to pursue those things.

Geach opines that Schopenhauer (who we also had reason to look at recently), despite his hostility to Christianity, was closer to the Christian view about this particular matter than most other non-Christians are, and closer than he himself realized. The Eastern religions that influenced Schopenhauer, says Geach, locate the source of our misery in ignorance, and prescribe enlightenment as the cure. But for Christianity, the true source is sin or evil will, and the remedy is conversion. Schopenhauer, with his emphasis on malign will as the source of human suffering, was in Geach’s estimation at least approximating the doctrine of original sin.

Geach says that the disordered orientation of the will that has become our second nature after the Fall “holds… in particular for two sorts of desire: erotic and combative” (p. 96). In both cases, fallen man has a tendency to indulge desire to excess, and to aim it at the wrong things, thereby becoming lecherous, perverse, quarrelsome, violent, and vengeful. People often characterize such human beings as beastly or animal-like, but as Geach notes, this is not quite right:

The great apes, our alleged cousins, rarely kill one another; war, as opposed to individual fights, is an unknown thing for them; and men are enormously more lustful than apes. It is not that desires shared with lower animals corrupt man’s will; his already corrupt will corrupts his animal instincts, and makes them assume forms of monstrous excess and perversity unknown in the animal world. (pp. 96-97)

We might in this connection recall the old saying that the corruption of the best is the worst. The same rationality and free choice that make possible marriage and family, religion and morality, science and philosophy, the arts and literature, sports, etc. also make possible the extreme sexual depravity into which the Western world has now sunk, the mass slaughter of our own children via abortion, endless and pointless wars, mass apostasy, vapid consumerism, gluttony and drug addiction, etc. Non-human animals are not capable of the former, but neither are they capable of the latter.

In an important insight, Geach says the following about the disorder in our desires that has become second nature after the Fall:

For our first parents, this rebellion in the house of life will have been unspeakably grievous. To find a hand striking in anger, or legs running away in fear, before the rational mind had time to act; to learn by painful self-discipline to restrain these irregular movements; this will have seemed to them no less pathological than when (as occasionally happens) a mental patient’s hand ceases to be under his conscious voluntary control but, for example, writes automatically words for which he is not consciously responsible. To us, their fallen posterity, such irregular motions are all too natural. For the root of evil is not in the disorderly passions, but in the will, perverse from our infancy up, that readily accepts the way we are as the way we ought to be. The will does not merely yield in the struggle or get taken by surprise: it positively identifies itself with perverse desires, and thereby makes them still more perverse. (pp. 95-96)

Suppose you are not an alcoholic and indeed have never been all that interested in drinking, but that you wake up one day with a sudden, irresistible and insatiable craving for whisky, and that this craving persists indefinitely and becomes the focus of everyday attention. What had once been easy (resisting the impulse to imbibe) now becomes so difficult that resistance is exhausting and routinely ends in failure. You would no doubt find this extremely disorienting and upsetting. This, as Geach’s remarks suggest, is analogous to the condition of our first parents after the Fall, when what I have called the “second nature” of disordered will immediately became superimposed on and began frustrating human nature.

But suppose instead that your parents had from your childhood onward encouraged you to drink, and that by young adulthood you had gotten so used to a general background buzz and regular episodes of outright drunkenness that you could not imagine any other way of living. The idea of not drinking has become unthinkable, or at least seemingly hopelessly unrealistic. “This is just the way I naturally am!” you think, and you might even enjoy being that way. Precisely because you do, though, your alcoholism is worsethan that of the alcoholic who struggles with his addiction, not better. This, Geach’s remarks suggest, is our condition many generations after the sin of our first parents. We identifyourselves with our disordered desires, taking them to be natural to us rather than reflective of damage to our nature.

For this reason, says Geach, “there was some truth in the insulting description used by Pagan Romans for Christians, ‘enemies of the human race’” (p. 99). For Christianity is indeed the enemy of what human beings have become as a result of original sin. Christianity opposes what people falsely assume is “natural” to them, but which is in fact only a corrupt “second nature” that has gotten superimposed on, and frustrates the realization of, their true nature. As a result, says Geach, “authentic Christianity must then at bottom be odious to the worldly man” (p. 100). Geach contrasts this “authentic Christianity” with the false kind that “urges[s] Christians to work loyally” for, and indeed to “advance,” the ideals of the worldly man – namely, the modernist Christianity that we saw Geach attack in a previous post.

(As I’ve discussed in posts like this one and this one, Aquinas has a lot to say about the self-deception, irrationality, and general breakdown in moral understanding to which those in thrall to sins of the flesh are especially prone. In another post I discussed the similar effects of the sin of wrath. Part of Geach’s point is that these particular kinds of disconnect with reality are not merely the result of actual sin, but have their roots in original sin.)

No collective salvation

Geach emphasizes that the doctrine of original sin is not a thesis of collective responsibility for individual sins, and that Christianity in fact rejects the idea of such collective responsibility. You and I and everyone else may have together inherited from our first parents a tendency toward disordered desire, but if I act on such desire in a particular case, I alone am guilty of that action and I alone must answer for it. But by the same token, says Geach:

It must always be remembered that salvation is individual. Just as there is a fashionable doctrine of collective guilt, so there is a doctrine that men have been collectively redeemed. But that is equally false with the other doctrine. (p. 100)

If the human race descended from our first parents is like a tree, then there is, Geach says, “no hope at all” for that tree as a whole. There is hope only for whatever individual branches from that tree can be grafted onto the new tree that begins with Christ. Switching to another biblical metaphor, that of the narrow gate to eternal life, Geach writes:

Though entering the gate leads you to the glorious company of Christ and the Saints and Angels, you must enter alone. If you want the pleasures of following a leader in a crowd, there is a broad and easy road for you, but it leads to destruction; solidarity with mankind at large is something a Christian must renounce once for all. (p. 101)

This suggests the following analogy (mine, not Geach’s). We are by nature social animals, and have a duty to assist each other in acquiring the material necessities of life. But that does not entail that anyone is entitled to be provided for by others utterly regardless of desert or willingness to make an effort. “If any man will not work, neither let him eat” (2 Thessalonians 3:10). Similarly, the counsel and prayers of fellow Christians and the saints’ treasury of merit assist us in finding salvation, but they do not guarantee that we will find it. There will be no spiritual freeloaders in heaven, no one who squeaks by because someone else repented for him. “Unless you repent you will all likewise perish” (Luke 13:3).

Related posts:

Geach’s argument against modernism

Geach on worshipping the right God

November 23, 2021

MacIntyre on human dignity

Recently, Alasdair MacIntyre presented a talk on the theme “Human Dignity: A Puzzling and Possibly Dangerous Idea?” at the Fall Conference of the de Nicola Center for Ethics and Culture at the University of Notre Dame. You can watch it on YouTube. It has gotten a lot of attention even beyond academic circles, which is not surprising given MacIntyre’s stature together with the question he raises in the title. What follows is a summary of the talk followed by my own comments. I’m only going to cover MacIntyre’s main themes; there are various details (such as MacIntyre’s comments on specific historical examples) for which you’ll have to listen to his talk.

Recently, Alasdair MacIntyre presented a talk on the theme “Human Dignity: A Puzzling and Possibly Dangerous Idea?” at the Fall Conference of the de Nicola Center for Ethics and Culture at the University of Notre Dame. You can watch it on YouTube. It has gotten a lot of attention even beyond academic circles, which is not surprising given MacIntyre’s stature together with the question he raises in the title. What follows is a summary of the talk followed by my own comments. I’m only going to cover MacIntyre’s main themes; there are various details (such as MacIntyre’s comments on specific historical examples) for which you’ll have to listen to his talk. Whose dignity? Which humans?

MacIntyre starts out by distinguishing between two conceptions of human dignity, one of which he evidently regards as unproblematic but which is not widely known today, and the other of which is widely appealed to today but, MacIntyre thinks, is problematic. According to this latter conception, dignity is something that all human beings have, and their having it entails that we owe every human being respect. Hence, according to this view of human dignity (and to use MacIntyre’s examples) we owe respect even to people who torture children, and to Goebbels and Stalin. This, MacIntyre notes, is a puzzling idea. But it is also vague exactly what this respect and dignity amount to.

MacIntyre says that this conception of human dignity became prevalent only after World War II, and that it is reflected in documents like the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights and in various post-war European constitutions. And its vagueness, he suggests, was deliberate, because it was designed to secure rhetorical agreement among people who did not agree on substantive matters (Catholics, Protestants, Jews, Muslims, atheists, conservatives, liberals, etc.).

A rival conception of human dignity is associated with Aquinas, and given exposition in the 20th century Thomist philosopher Charles De Koninck’s essay “The Primacy of the Common Good against the Personalists.” There are four components to this conception:

1. What distinguishes human beings from other creatures is the end toward which we are directed, which is to know and love God. The dignity of this end is what gives us our dignity.

2. There are further ends associated with this end, most importantly the common good of the society of which we are parts. This entails a rejection of individualism.

3. Whether we achieve these ends is up to us, given our powers as rational agents with free choice.

4. Insofar as we fail to direct ourselves to these ends, we lose our dignity or worth, and no one any longer has reason to treat us as possessing it.

The Aquinas/De Koninck conception of human dignity differs from the post-war conception in three crucial ways. First, the post-war conception was designed to secure agreement between people holding various different modern moral and political views, whereas Aquinas’s account is deeply at odds with those views. Second, for Aquinas, individuals can and do lose their dignity, whereas for the post-war conception, no one ever loses it. Third, the post-war conception holds that we have dignity simply by virtue of being human, whereas for Aquinas, it is not what we are that gives us dignity, but rather what we should became that gives it to us.

Three rival versions of inquiry into dignity

MacIntyre next notes that there are three basic alternative approaches one could take toward these rival accounts of human dignity. First, one could reject both of them. Second, one could reject what he calls the post-war conception. Third, one could reject the Aquinas/De Koninck conception. For the purposes of this talk, MacIntyre focuses on weighing the respective merits of the post-war and Aquinas/De Koninck accounts (rather than considering some third alternative or throwing out the notion of dignity altogether).

Why have many people found the post-war conception attractive? MacIntyre suggests that there are six or seven reasons. The view that all human beings have dignity rules out slavery. It rules out other kinds of mistreatment of people. It rules out killing the innocent. It rules out insulting and humiliating people. It rules out arbitrary discrimination against people. It requires us to give other people’s views a fair hearing before judging them. And it rules out lying to people (though MacIntyre says that people now seem to be widely abandoning the idea that it is wrong to lie).

But MacIntyre next asks: What gives us a rational justification for believing that all human beings really do have dignity in a sense that would rule out these things? The two main contemporary justifications are contractarian and Kantian. But these attempted justifications are at odds with one another, and the notion of human dignity has also been subjected to consequentialist objections by writers like Peter Singer. The upshot is that attempts to justify the post-war conception of human dignity are no less controversial than that conception itself is.

So, the post-war conception is hard to justify. But MacIntyre also suggests that it may, in addition, be positively harmful. For it is an entirely negative conception, requiring of us only that we do not do certain things to people. But in a sound morality, MacIntyre thinks, negative precepts have their importance only relative to positive ones.

For example, suppose we free a group of slaves, but leave it at that, and do nothing positively to improve the unhappy condition slavery has reduced them to. Or suppose we outlaw abortion, but do nothing to remedy a situation in which the children who are born are not sufficiently provided for. It is not plausible to suppose that respect for the dignity of the slaves or the children requires only the negative duty of not enslaving or aborting them, with no positive obligations to them beyond that.

MacIntyre then revisits the Aquinas/De Koninck conception of human dignity. He notes that it distinguishes between dignity and utility, where the latter involves having value only as a means and the former involves having value as an end. And again, it holds that our dignity derives from our having the end of knowing and loving God. This end in turn derives from our nature as rational agents. The reason is that the highest realization of our rationality is having the fullest possible understanding of things, and that entails knowing God as first cause. And the highest realization of our having wills is to love the most perfect object of desire, and that is God. Our dignity thus derives not from what we are actually, but what we are potentially, i.e. knowers and lovers of God.

Again, he notes that on the Aquinas/De Koninck conception, another of our ends is contributing to the common good, and that this entails rejecting individualism. This implies in turn various positive obligations rather than a mere negative duty not to do certain things. And MacIntyre suggests (acknowledging that this is his own inference rather than De Koninck’s) that among the things this would entail is provision of adequate childcare services for all, education for all, employment for all, and so on.

After dignity

MacIntyre then reiterates the point that on the Aquinas/De Koninck conception of human dignity, unlike the post-war conception, our dignity can be lost by sinning and turning away from God. He notes that for Aquinas, a human being who does this is worse than a beast and that Aquinas links this to the legitimacy of the death penalty.

Does this mean that we do not owe such sinful human beings justice and charity? MacIntyre says that that does not follow. However, he notes that any appeal to justice necessarily presupposes a shared account of what it is to be a member of a flourishing social order (family, larger political community, etc.). As long as there is no agreement on that, appeals to justice will not be effective.

Relatedly, he notes at the end of his talk, in recent years Catholics have often supposed that when dealing with a secular audience, they can appeal to the notion of human dignity in order to justify the Church’s teaching on various moral issues. But this is a mistake, because there is no agreement between Catholics and the secular world on the rival background assumptions that are necessary to give the notion of dignity content.

During the Q and A period, MacIntyre elaborated on some of these points. John O’Callaghan suggested that we need to distinguish between losing one’s dignity, and failing to live up toit. Why, he asks, can’t we say merely that a sinner has failed to live up to it? Why say that the sinner loses his dignity? Furthermore, if a Hitler or a Goebbels loses his dignity, does this entail that we could torture them? If not, why not?

In response, MacIntyre says, first, that we should not torture such people, but not because they have dignity. Rather, we should not do so because it would be contrary to justice to do so. He also claims that at least for Aquinas, it’s not merely that a sinner has turned away from the end of knowing and loving God, but that, even if only temporarily, he is no longer directed to that end.

MacIntyre here also makes a couple of interesting side remarks. He says that the Laval Thomism associated with De Koninck was the most important strain of Thomism in the twentieth century, and that Ralph McInerny, who was the foremost exponent of Laval Thomism after De Koninck, was the most important philosopher ever to teach at the University of Notre Dame. MacIntyre says that other Notre Dame philosophers wouldn’t agree with him about this, but that that simply reflects ignorance.

Melissa Moschella then suggested that the notion of human dignity does more philosophical work than MacIntyre gives it credit for. For example, in bioethics it provides a way of grounding the idea that all human beings (unlike non-human animals) share common membership of the moral community. In reply, MacIntyre says that the concept of justice is independent of and prior to the notion of dignity, so that we don’t need the notion of dignity in order to do the work in question.

Ben Conroy then suggested that the Thomistic conception of dignity that MacIntyre favors might be accused of having had some bad consequences, just as the modern conception of dignity has. His example is excessively harsh treatment of heretics during the Middle Ages. In reply, MacIntyre says, first, that as a matter of history, there is no reason to think that Aquinas’s conception of dignity, specifically, influenced the way heretics were treated. Second, he says that when we consider how heretics ought to be treated, it is really the concept of justice that is doing the work, rather than the concept of human dignity.

He notes that on an Aristotelian conception of justice (unlike, say, John Rawls’s conception) treating someone justly by giving him his due requires knowing what it is to be a member of a flourishing family, workplace, or other social community. And in the case of the Church’s dealing with heretics, he says, the problem was that the Church did not have an adequate understanding of what dealing with them justly requires.

Finally, Chris Wolfe asked whether, on Aquinas’s view as interpreted by De Koninck, the nation state, and not just the local community, can be said to have a common good. MacIntyre’s answer is that the modern state is problematic as an institution, but that it is nevertheless there, so that we have to work within its organizational framework in order to achieve common goods. It isn’t itself really an instrument of the common good, but it does afford resources and obstacles vis-à-vis the common good. An example he gives of a resource that it makes possible is maternity leave.

Some comments on MacIntyre on dignity

Again, that’s all just a summary of the main thread of MacIntyre’s talk, which I thought I’d write up to help organize my own thoughts and give context for the comments to follow. It also seems to me that some other people who have commented on MacIntyre’s talk have cherry-picked certain remarks that are of special interest to them, but which could give a distorted picture of the talk’s overall theme to someone who hasn’t heard it. So, a summary seemed worthwhile. I have tried simply to report what he said, but if any reader thinks I’ve misunderstood or misrepresented him in any way, let me know.

Here are my own comments. First, I strongly sympathize with MacIntyre’s general theme that the notion of human dignity is more problematic and less interesting than many contemporary Catholics suppose. Indeed, I’ve made the point myself several times over the years (e.g. hereand here). Shouting “human dignity!” does exactly zero work in justifying claims about abortion, euthanasia, etc. because what human dignity amounts to and what it entails are themselves no less contested than those issues are. In order to show that respect for human dignity rules out those things, you need to do the hard work of setting out the natural law reasoning that shows that they are intrinsically evil. But once you’ve done that, talk of “human dignity” drops away as otiose.

Having said that, I’m not convinced by some of the specific points MacIntyre makes. For example, it doesn’t seem to me to be correct to say that what he calls the post-war conception of human dignity amounts merely to a set of negative requirements. For somepeople, such as libertarians, it might, but that is because they’re libertarians, not because they’re appealing to human dignity. A Rawlsian liberal, a social democrat, or a socialist might claim that human dignity doesrequire various positive obligations, rather than merely negative duties to avoid certain ways of treating people.

MacIntyre might respond that these positive obligations really follow from the views about justice that these theorists have, and not from the notion of dignity. But says who? Precisely because the notion of dignity is so vague (as MacIntyre also complains), it’s not clear why it would have to entail only a set of negative requirements.

In this way, two of MacIntyre’s points seem to me to be in tension with one another. On the one hand, he says that the post-war notion of dignity is too vague, but on the other hand he also suggests that it may entail only negative obligations. Well, if it really does allow for only negative obligations, then it’s not that vague after all. But if the post-war conception of dignity is vague – as I agree it is – then it doesn’t clearly rule out positive obligations, because it doesn’t clearly rule out much at all. (Indeed, it doesn’t by itself even entail all negativeobligations – for example, some people think it doesn’t rule out abortion and euthanasia.) Hence, it seems to me that MacIntyre should have just stuck with the objection that the post-war conception is too vague, and not bothered with the claim that it entails only negative obligations.

A second problem is that I don’t think MacIntyre’s response to John O’Callaghan’s point really works. After all, a sinning human being is still a human being, and thus still has a human nature, and thus still has the end entailed by having the nature, which is knowing God (albeit not the intimate knowledge of the divine essence entailed by the beatific vision). And if the sinner is baptized, he remains baptized after sinning and thus still has the same supernatural end of the beatific vision (even if he has frustrated the realization of this end). The problem is not that he has lost the ends in question, but that he is not doing what is necessary to realize them. Hence it seems more apt to say, as John suggests, that he is not living up to the demands of his dignity, rather than that he has lost his dignity. (In general, the failure clearly to distinguish and relate what is true of us by nature and what is true of us by virtue of grace may pose problems for MacIntyre’s treatment of Aquinas.)

A way to reconcile MacIntyre’s and John’s views is to appeal to a distinction (who was also influenced by De Koninck), between the “substantive dignity” that follows simply upon having a certain nature and the “acquired dignity” of someone who has obeyed the divine law. The sinner loses the second (which is perhaps what MacIntyre wants to emphasize) while retaining the first (which is perhaps what John O’Callaghan wants to emphasize).

I am strongly sympathetic to MacIntyre’s emphasis on the common good and criticism of individualism. But I am not so keen on the examples he gives of how to secure the former, such as maternity leave, childcare, and the like. To be sure, MacIntyre only mentions such examples briefly and in passing and doesn’t elaborate on exactly what he has in mind. But the problem with simply citing such examples without elaborating on them is that they cannot properly be understood without factoring in the principle of subsidiarity, which is crucial to understanding the Thomistic conception of the common good.

Take child care. Is the provision of adequate child care essential to a just society ordered toward the common good? Of course. But exactly who is to provide for it? For example, who is responsible for providing child care for my children? The answer is that I am. What if I am unable to do it? The answer is that the primary responsibility for assisting me lies with my extended family. What if they are unable to do it? The answer is that the local Church and local community more generally ought to offer assistance. Is there a role for more centralized authorities, such as the state or federal government? Yes, but only to the extent that the sources of aid closer to those who need it are not sufficient.

Hence while Thomistic natural law theory (and Catholic social teaching, which was developed in light of it) rule out libertarianism, they also rule out socialism, as well as (I would argue) social democracy and Rawlsian egalitarian liberalism. Now, under the influence of these latter doctrines, most people today, when they think of aspects of the common good like the ones MacIntyre cites, tend reflexively to think of centralized government as the agency that ought to provide them. And that is contrary to the principle of subsidiarity, which, while it requires larger-scale levels of society (such as centralized government) to aid lower-level ones (like the family) when strictly necessary, at the same time and as a matter of justiceforbids the larger-scale levels from doing so where it is not necessary. In other words, whereas modern egalitarians think of central government as the provider of first resort, the natural law tradition and Catholic social teaching think of it as the provider of last resort. (It isstill a provider in that case, though, contrary to libertarianism.)

The point of this is to safeguard the independence of the family and local communities, which are the primary context within which we manifest our social nature and realize the common good. Without an accent on the family and subsidiarity, MacIntyre’s pitting of the common good against individualism – with which, again, I strongly agree – could be understood in a way that reflects, not Thomistic natural law, but rather modern egalitarian doctrines which Thomists ought to resist just as they resist individualism.

Related reading:

The catastrophic spider [On Kant on human dignity]

November 21, 2021

The Feast of Christ the King

Today Catholics celebrate the Feast of Christ the King, which makes it an appropriate time to remind ourselves of what the Church teaches the faithful about their duty to bring their religion to bear on political matters. “But wait,” you might ask, “hasn’t the Church since Vatican II adopted the American attitude of keeping religion out of politics, and making of it a purely private affair?” Absolutely not. Even

Dignitatis Humanae

, Vatican II’s famous declaration on religious freedom, insists that it “leaves untouched traditional Catholic doctrine on the moral duty of men

and societies

toward the true religion and toward the one Church of Christ” (emphasis added).

Today Catholics celebrate the Feast of Christ the King, which makes it an appropriate time to remind ourselves of what the Church teaches the faithful about their duty to bring their religion to bear on political matters. “But wait,” you might ask, “hasn’t the Church since Vatican II adopted the American attitude of keeping religion out of politics, and making of it a purely private affair?” Absolutely not. Even

Dignitatis Humanae

, Vatican II’s famous declaration on religious freedom, insists that it “leaves untouched traditional Catholic doctrine on the moral duty of men

and societies

toward the true religion and toward the one Church of Christ” (emphasis added). What does that entail? Here are some relevant passages from the current Catechism of the Catholic Church, promulgated by Pope St. John Paul II (emphasis added):

The duty of offering God genuine worship concerns man both individually and socially. This is “the traditional Catholic teaching on the moral duty of individuals and societies toward the true religion and the one Church of Christ.” By constantly evangelizing men, the Church works toward enabling them “to infuse the Christian spirit into the mentality and mores, laws and structures of the communities in which [they] live.” The social duty of Christians is to respect and awaken in each man the love of the true and the good. It requires them to make known the worship of the one true religion which subsists in the Catholic and apostolic Church. Christians are called to be the light of the world. Thus, the Church shows forth the kingship of Christ over all creation and in particular over human societies. (2105)

And against the idea that it is best for the state instead to be neutral about the Catholic Faith – not hostile to it, but not being influenced by it either – the Catechism says:

Every institution is inspired, at least implicitly, by a vision of man and his destiny, from which it derives the point of reference for its judgment, its hierarchy of values, its line of conduct. Most societies have formed their institutions in the recognition of a certain preeminence of man over things. Only the divinely revealed religion has clearly recognized man's origin and destiny in God, the Creator and Redeemer. The Church invites political authorities to measure their judgments and decisions against this inspired truth about God and man:

Societies not recognizing this vision or rejecting it in the name of their independence from God are brought to seek their criteria and goal in themselves or to borrow them from some ideology. Since they do not admit that one can defend an objective criterion of good and evil, they arrogate to themselves an explicit or implicit totalitarian power over man and his destiny, as history shows. (2244)

It is a part of the Church's mission “to pass moral judgments even in matters related to politics, whenever the fundamental rights of man or the salvation of souls requires it.” (2246)

Every society's judgments and conduct reflect a vision of man and his destiny. Without the light the Gospel sheds on God and man, societies easily become totalitarian. (2257)

There is also the Compendium of the Catechism of the Catholic Church promulgated by Pope Benedict XVI. In response to the question “How should authority be exercised in the various spheres of civil society?” the Compendium answers:

All those who exercise authority should seek the interests of the community before their own interest and allow their decisions to be inspired by the truth about God, about man and about the world. (463)

Then there is the Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church, which teaches that “religious freedom is not a moral licence to adhere to error, nor as an implicit right to error” (421); that “because of its historical and cultural ties to a nation, a religious community might be given special recognition on the part of the State” (423); that “the mutual autonomy of the Church and the political community does not entail a separation that excludes cooperation” (425); and that “the Church has the right to the legal recognition of her proper identity” (426).

Of course, all of these documents also teach that non-Catholics no less than Catholics have a right to religious freedom, and none of them calls for what I have elsewhere called “hard integralism.” But they show that the Church clearly teaches that Catholic voters and politicians can and should be guided by “the true religion,” and not merely by some thin common ground between religions, much less by the even thinner common ground between religious believers and secularists.

These are all post-Vatican II sources. But it’s also a good day to re-read Pope Pius XI’s Quas Primas. Viva Cristo Rey!

Further reading:

A clarification on integralism

November 18, 2021

Geach’s argument against modernism

Catholic philosopher Peter Geach’s book

Providence and Evil

is interesting not only for what it says about the topics referred to in the title, but also for its many insights and arguments concerning other matters that Geach treats along the way. Among these passing remarks is a brief but trenchant critique of those who propose a “denatured” brand of Christianity in the name of “man’s evolution and progress” (p. 85). Theirs is the view that Christian tradition is “mutable,” so that “with the progress of knowledge a doctrine hitherto continuously taught in one sense now needs to be construed in another sense” (pp. 86-87). Geach doesn’t use the label “modernism,” but that is what he is talking about.

Catholic philosopher Peter Geach’s book

Providence and Evil

is interesting not only for what it says about the topics referred to in the title, but also for its many insights and arguments concerning other matters that Geach treats along the way. Among these passing remarks is a brief but trenchant critique of those who propose a “denatured” brand of Christianity in the name of “man’s evolution and progress” (p. 85). Theirs is the view that Christian tradition is “mutable,” so that “with the progress of knowledge a doctrine hitherto continuously taught in one sense now needs to be construed in another sense” (pp. 86-87). Geach doesn’t use the label “modernism,” but that is what he is talking about. One problem with this sort of view, Geach points out, is that we could never have grounds for believing it. For there are really only two possible sources for a theological doctrine, either reason or revelation. To be more precise, one way we might come to know it is via philosophical argumentation whose premises are completely independent of revelation. Philosophical arguments for God’s existence would be an example. The other way is through special divine revelation, such as a message given through a prophet whose authority is backed by miracles. The doctrine of the Incarnation would be an example. Christianity traditionally appeals to both sources of knowledge, but what is distinctively Christian comes through revelation.

Now, the problem for the modernist identified by Geach is this. Modernism is a specifically Christian view. The modernist claims (falsely, to be sure, but still he claims) to preserve what is essential to Christian teaching. And what is essential to this teaching, Christianity says, was divinely revealed at the time of Christ and the apostles. Hence modernism cannot appeal to a purely philosophical argument to justify itself. It has to make some appeal to the content of this divine revelation given at the time of the Church’s origin.

But how do we know that something really is part of the content of this revelation? Geach points out that continuity of teaching is a necessary condition of our knowing it. To be sure, it is not a sufficientcondition. If some doctrine has consistently been taught by the Church for two millennia, that does not by itself guarantee that it is true, since we need some independent reason to think it really was divinely revealed two millennia ago. But, again, it is a necessary condition. If some doctrine has not been taught for two millennia, or even conflicts with what has been taught for two millennia, it can hardly be known to have been part of the divine revelation that was given two millennia ago. And in that case it cannot be justified by appeal to that revelation.

The problem for the modernist is that the new doctrines he wants to teach, or the new interpretations he wants to give old doctrines, by definition cannot be traced to that original revelation from two millennia ago. If they could be, they would not be new. Hence the modernist cannot defend them by appealing to revelation any more than he can defend them by appealing to philosophical arguments. And since those are the only possible ways he could have defended them, he cannot defend them at all. They simply float in midair, ungrounded. Thus does Geach say of the modernist:

His teaching will be a matter of learned conjectures intermixed with such fragments, few or many, of the old tradition as he chooses still to believe. He may choose to believe all this; but he will scarcely persuade a rational outsider, and he can claim no authority that should bind the conscience of a Christian. (p. 86)

Modernism is in this way an inevitably self-defeatingposition. By rejecting the continuous teaching of tradition, it rejects the only basis for its own teaching that it might have had.

In my early years as a grad student I took a class with John Hick (who was one of the best teachers I ever had, even if his philosophical and theological views left much to be desired). Hick was a modernist if ever there was one, and an influential proponent of the religious pluralist view that all of the world religions are more or less equally good and salvific. Now, you can’t coherently take such a view unless you drastically water down the truth claims of these religions, since those claims conflict with one another. And Hick acknowledged (in conversation – I don’t know offhand if he ever said this in print) that few people were likely to convert to Christianity or any other religion in such watered-down forms. There simply isn’t much point in converting to Christianity if you’re told from the get-go that doctrines like the Trinity and the Incarnation are not really true, but just poetic ways of speaking. Hence, for views like his to prevail, Hick acknowledged, people have to start by believing the more traditional doctrines and then gradually move away from them under the influence of arguments like his.

This illustrates how modernism is psychologically and sociologically parasitic on the traditional doctrines it rejects. But Geach’s point is essentially that modernism is also logically parasitic on the doctrines it rejects. For it has no freestanding basis, but presupposes the traditional view that there really was a divine revelation two millennia ago, of which (modernism claims) it is itself at long last the correct interpretation.

Yet at the same time, and in the manner we’ve seen, modernism subverts any confidence we could have in a claim to know such a revelation. If you say “Such-and-such really was revealed two millennia ago, but the Church has misunderstood it for two millennia,” that inevitably raises the question “If you’ve been getting the content of the revelation wrong for that long, why suppose you’re right even about there having been any revelation in the first place?” Hence it is no surprise that it is only ever theologically conservative brands of Christianity that thrive, while liberal denominations shrink and die out. Logically, and thus psychologically and sociologically, modernism inevitably destroys the faith it claims to be preserving by adapting it to modern times. Modernism is in this way like a cancer that slowly kills the host on whose life it depends.

There is another irony in modernism, and one to which Geach also calls our attention. He writes:

It is often said that in our world and time the Christian story is irrelevant. A curious adjective, when the grimmest Christian prophecies of the last days might seem, even by human calculation, all too likely to be literally fulfilled. (p. 84)

If the prophecies in question seemed close to fulfilment in the 1970s, when Geach was writing, how much more so in light of the unprecedented moral depravity and runaway heterodoxy of the present day? Be that as it may, though modernism claims to save Christianity from being “irrelevant,” it is in reality an instance of the widespread apostasy from the Catholic faith that is among the things grimly prophesied by Christ and the apostles. In that way, the prevalence of modernism inadvertently confirms the predictions of the traditional theology it aims to subvert.

Related reading:

November 13, 2021

Aquinas on the relative importance of pastors and theologians

In his book

Thomas Aquinas: His Personality and Thought

, Martin Grabmann notes:

In his book

Thomas Aquinas: His Personality and Thought

, Martin Grabmann notes: In a passage of his… [Aquinas] touches upon the question, whether the pastors of souls or the professors of theology have a more important position in the life of the Church, and he decides in favor of the latter. He gives the following reason for his view: In the construction of a building the architect, who conceives the plan and directs the construction, stands above the workmen who actually put up the building. In the construction of the divine edifice of the Church and the care of souls, the position of architect is held by the bishops, but also by the theology professors, who study and teach the manner in which the care of souls is to be conducted. (p. 5)

The passage Grabmann is discussing is from Aquinas’s Quodlibetal Questions, in Quodlibet I, Question 7, Article 2. Aquinas there further develops the point summarized by Grabmann as follows:

Teachers of theology are like principal architects… since they investigate and teach others how they ought to go about saving souls. Absolutely speaking, therefore, teaching theology is better than devoting particular attention to the salvation of this or that soul… Even reason itself shows us that it is better to teach the truths of salvation to those who can benefit both themselves and others rather than to the simple who can only benefit themselves. (Nevitt and Davies translation, p. 204)

Note that Aquinas’s teaching here is diametrically opposed to what passes for wisdom in many ecclesiastical circles today, including Catholic ones. The “pastoral” is often contrasted with and elevated above theology, with the latter being caricatured as dry and irrelevant to the Christian life. Indeed, as I noted in a post not too long ago, “pastoral” often functions as a weasel word – that is to say, in this context, a word that sucks the meaning out of a theological term and insinuates an opposite meaning. In this way, “pastoral” considerations are alleged to justify ignoring or even contradicting the clear teaching of orthodox theology (e.g. by permitting adulterers to receive absolution and take Holy Communion without a firm purpose of amendment).

For Aquinas, by contrast, there can be no conflict whatsoever between the deliverances of sound theology on the one hand and pastoral considerations on the other. On the contrary, to be genuinely pastoral is precisely to apply sound theology to concrete circumstances. If your pastoral instincts tell you to soft pedal or ignore what such theology says, the problem is not with the theology but with your pastoral instincts. Nor does the generality of the theologian’s conclusions somehow make them less applicable to concrete cases. Rather, it makes them applicable precisely to more cases rather than to fewer. True, applying them to concrete cases sometimes requires “discernment” (another weasel word). But that is precisely a matter of finding out how to apply them to each case, not of finding a way to justify ignoringthem in some cases.

Yet those who pit the pastoral against the theological are often not in fact opposed at all to letting theology per se guide their pastoral practice. Rather, they simply don’t like a certain kind of theology (typically, the orthodox kind), and use purportedly “pastoral” considerations as an excuse to reject it. Or, if they do sincerely think of themselves as eschewing theology, they are often inadvertently doing so on the basis of what amounts to a rival theological position. In The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, John Maynard Keynes famously wrote:

The ideas of economists and political philosophers, both when they are right and when they are wrong, are more powerful than is commonly understood. Indeed the world is ruled by little else. Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist. Madmen in authority, who hear voices in the air, are distilling their frenzy from some academic scribbler of a few years back. I am sure that the power of vested interests is vastly exaggerated compared with the gradual encroachment of ideas.

End quote. What is true in economics and political philosophy is true too in theology. Those who pit the pastoral against theology often do so, whether wittingly or unwittingly, under the influence of modernism, the heresy according to which traditional theological positions ought to be modified or abandoned if they conflict with “lived experience,” the actual “praxis” of the faithful, or what have you. The pretense is that the pastor is more sensitive to such considerations than the theologian is, but what is really meant is that the pastor influenced by modernist theology is more sensitive to them. (Pastors whose knowledge of the “praxis” and “lived experience” of their flocks leads them to affirmthe value of traditional theology are seldom listened to by those who most loudly proclaim themselves to be “pastoral.”)

Inevitably, as Aquinas sees, the question is not whetherpastors will be guided by theology, but rather which theology will guide them. Wherever the pastor ends up taking his flock, some theologian is always in the driver’s seat.

November 4, 2021

The politics of chastity

Chastity is the virtue governing the proper use of sexuality. My article “The Politics of Chastity”appears in the Fall 2021 issue of Nova et Vetera. It is part of a symposium on Reinhard Hütter’s book

Bound for Beatitude: A Thomistic Study in Eschatology and Ethics

, which includes an essay on the subject of chastity and pornography that inspired my own article. The article addresses the nature of chastity, vices contrary to chastity, the effect such vices (and in particular pornography) have on society at large, and the implications all of this has for political philosophy and in particular for the question of integralism.

Chastity is the virtue governing the proper use of sexuality. My article “The Politics of Chastity”appears in the Fall 2021 issue of Nova et Vetera. It is part of a symposium on Reinhard Hütter’s book

Bound for Beatitude: A Thomistic Study in Eschatology and Ethics

, which includes an essay on the subject of chastity and pornography that inspired my own article. The article addresses the nature of chastity, vices contrary to chastity, the effect such vices (and in particular pornography) have on society at large, and the implications all of this has for political philosophy and in particular for the question of integralism. Related reading:

November 2, 2021

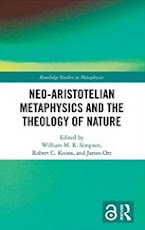

Neo-Aristotelian Metaphysics and the Theology of Nature

Routledge has just published the new anthology

Neo-Aristotelian Metaphysics and the Theology of Nature

, edited By William M. R. Simpson, Robert C. Koons, and James Orr. My article “Natural and Supernatural” appears in the volume. Here is the abstract for the article:

Routledge has just published the new anthology

Neo-Aristotelian Metaphysics and the Theology of Nature

, edited By William M. R. Simpson, Robert C. Koons, and James Orr. My article “Natural and Supernatural” appears in the volume. Here is the abstract for the article: The “supernatural,” as that term is traditionally used in theology, is that which is beyond the power of the natural order to produce on its own. Hence it can be produced only by what has causal power superior to that of anything in the natural order, namely the divine cause of the natural order. Insofar as the natural order depends on this supernatural cause, the supernatural is metaphysically prior to the natural. However, the natural is epistemologically prior to the supernatural, insofar as we cannot form a conception of the supernatural except by contrast with the natural, and cannot know whether there is such a thing as the supernatural unless we can reason to its existence from the existence of the natural order. A proper understanding of the supernatural thus presupposes a proper understanding of the natural order and of the causal relation between that order and its cause. This chapter offers an account of these matters and of their implications for theological issues concerning causal arguments for God’s existence, divine conservation and concurrence, miracles, nature and grace, faith and reason, and the notion of a theological mystery (viz. what is beyond the power of the intellect to discover on its own).

Each of the editors contributes an article to the volume. The other contributors are John Marenbon, David Oderberg, Stephen Boulter, Timothy O’Connor, Janice Chik, Daniel De Haan, Antonio Ramos-Diaz, Christopher Hauser, Travis Dumsday, Ross Inman, Anne Peterson, Alexander Pruss, Simon Kopf, and Anna Marmodoro. The essays cover a wide variety of topics, including quantum mechanics, evolution, the hierarchy of being, free will, non-human animals, logic and mathematics, life after death, angels, hylomorphism, and much else. More information is available at Cambridge University's Faculty of Divinity website, and at the Routledge website, where you’ll see that a couple of the chapters are available via Open Access, and that the volume is available in an affordable eBook edition.

October 29, 2021

Adventures in the Old Atheism, Part VI: Schopenhauer

Our series has examined how atheists of earlier generations often exhibited a higher degree of moral and/or metaphysical gravitas than the sophomoric New Atheists of more recent vintage. As we’ve seen, this is true of Nietzsche, Sartre, Freud, Marx, and even Woody Allen. There is arguably even more in the way of metaphysical and moral gravitas to be found in our next subject, Arthur Schopenhauer. Plus, I think it has to be said, the best hair. So let’s have a look, if you’re willing.

Heavy meta

Schopenhauer’s magnum opus The World as Will and Ideafamously begins with the sentence: “The world is my idea.” As opening lines go, that ain’t bad. It’s a grabber. What does it mean? The thesis is the Kantian one that the world as we know it in experience is not reality as it is in itself, but only reality as represented. (Vorstellung, translated as “idea” in this line and in the book’s title, is sometimes translated “representation” instead.) Schopenhauer’s philosophy is essentially a continuation of Kant’s, though also, he thought, a partial correction of it.

The correction involves a greater openness than Kant exhibited toward heavy-duty speculative metaphysics. To be sure, Schopenhauer followed Kant to some extent in the project of clipping the traditional metaphysician’s wings. He has much of interest to say about the Principle of Sufficient Reason, having devoted his first book to the topic. On the Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason identifies four aspects of reality, each of which is intelligible in its own way: the phenomenal world of physical objects; the logical relations between concepts and propositions; time and space as described in terms of arithmetic and geometry; and the self considered as the subject of acts of the will. Schopenhauer regarded the Principle of Sufficient Reason as a unifying abstraction from the principles of intelligibility governing these four domains. But like a good Kantian (and unlike rationalists such as Leibniz), he took the principle to apply only within the phenomenal world, so that it couldn’t ground an argument for the existence of God as cause of the phenomenal world. Schopenhauer also had a high regard for Plato, and for the Theory of Forms in particular. But the Forms too do not in his view reflect reality as it is in itself, so that Schopenhauer is no more a Platonic metaphysician than he is a rationalist one.

Still, he did not agree with Kant that we could know nothingof reality as it is itself (i.e. the noumenal world, to use the Kantian jargon). Schopenhauer thought we could know something of it, though not via speculative metaphysical arguments. Rather, we know it from consciousness of ourselves, and what we know of it, specifically, is that it is will or volition – it is the impulseor striving we know in awareness of our own actions.

In order properly to understand this, we need immediately to note some crucial qualifications. You might wonder whether Schopenhauer is making a claim to the effect that the nature of all reality as it is in itself is to be found in what you experience when (say) you will to reach your hand into the bag of Doritos for another chip. That would indeed sound odd. But he is not saying that, or not quite. In experiencing this action, you experience it as involving several distinct objects and events – you, your hand, the bag of Doritos, the particular chip you take hold of, the moment of deciding to grab it, the later moment of actually taking hold of it, and so on. All of that reflects merely the phenomenalworld, not the noumenal world. It is all just the world as it appears to you, not the world as it is in itself. We catch a glimpse of the world as it is in itself only when we subtract all of that, and focus on the residue that remains – the sheer impulse toward acting that is common to this action and all others.

But it is not just human action that reflects this will or volition. It is, for Schopenhauer, evident in instinctual animal behavior, in a plant’s growing toward the light of the sun, and in a stone’s falling toward the earth. Will as he understands it is not – as it is for, say, Aquinas – necessarily associated with intellect. It is a more general notion, similar to what Aquinas means by appetite, a tending toward activity. This might seem to entail finality or teleology (as it does for Aquinas), but for Schopenhauer, will is blind. It simply aims, but not toward any good. It is a pointless striving or impulse.

Reality bites

This is the deep reason for Schopenhauer’s famous pessimism. It might seem, at first glance, that Schopenhauer’s metaphysics is broadly idealistic or even pantheistic in character. The noumenal will he posits is a single immaterial, undifferentiated, spaceless, timeless, uncaused reality. For the notions of differentiation, materiality, space, time, and causation apply only to the phenomenal world. That might make the noumenal world seem God-like, especially given that “will” suggests, at first hearing, a mind-like reality. And since the noumenal world is just the same thing as the phenomenal world, but considered in its true, inner nature, it might seem that Schopenhauer is committed to the view that all being is identical to this mind-like or God-like reality.

But, again, will as Schopenhauer understands it is not associated with intellect and it does not aim at the good or indeed at anything. Blind and pointless, it can never find satisfaction. This, in Schopenhauer’s view, is the deep explanation of all suffering. Suffering is the inevitable manifestation of the pointlessness of the blind will or aimless striving that underlies all reality. The phenomenal world of our experience is malign because the noumenal world beneath it is malign. Hence, though initially it might seem that Schopenhauer is committed to something comparable to Hindu pantheism (and he did indeed regard the Upanishads with respect), it is really an atheistic Buddhism, with its notion of tanhaor craving as the source of all suffering, that is a closer Eastern analogue of his position.

There is in Schopenhauer’s atheism, then, no cheap attribution of human unhappiness to religion, or to ignorance of science, or to bad political structures, the usual scapegoats posited by modern secularists. The source of unhappiness goes much deeper than all of that and would simply reappear in other forms however secularized we become, however much knowledge we acquire, and however we reform our institutions. Indeed, Schopenhauer had some respect for religions like Christianity, Hinduism, and Buddhism insofar as they recognized suffering to be simply part of the human condition, and tried to mitigate it.

Say what you will about Schopenhauer’s metaphysics, it is not the superficial scientism of pop physics bestsellers and the New Atheism, and it does not yield the chirpy optimism of moronic slogans like the notorious “There’s probably no God. Now stop worrying and enjoy your life.”

Schopenhauer? I barely know her!

When I speak of Schopenhauer’s moral gravitas, I am emphatically not talking about his personal moral character. He was not a nice guy. True, he did talk the talk of compassion and asceticism, and he was bound to develop such an ethics given his metaphysics. But his personal life was no model of either. Ascetic self-denial was hardly on display in his self-promoting attempt to draw students way from Hegel at the University of Berlin, by scheduling his lectures at the same time as those given by the then far more famous philosopher. (The result was famously disastrous for Schopenhauer.) Much worse, and the opposite of compassionate, was the notorious episode of his throwing a woman down the stairwell outside the door to his rooms, because he judged that she was making too much noise. (She was seriously injured and he had to pay her compensation for the rest of her life.)

Still, he did recommend an austere morality, rather than the libertinism that many people (wrongly) suppose must follow from an atheistic metaphysics. Like a Buddhist, Schopenhauer regarded resistance to our cravings, rather than indulgence of them, as the surest way to remedy suffering. Now, for Schopenhauer, the will that is the source of suffering is to be conceived of, first and foremost, as the will to live. You might think, then, that he would recommend suicide, but that is the reverse of the truth. Once again echoing Buddhism, he saw suicide as in fact just one more indulgence of desire, and thus to be avoided rather than commended.

Then there is sex, which exists for the sake of reproduction, the generation of new living things. Everyone knows this, of course, but the deep irrationality into which the indulgence of disordered desire has plunged modern people has led them to adopt the idiotic pretense that procreation is somehow merely incidental to sex. Schopenhauer was under no such illusions. The power and unruliness of the sexual drive was, for him, the clearest manifestation of the will to live and the way it brings about unhappiness. It mercilessly pushes us into romantic illusions, irrational decisions, and the compulsive scratching of an itch that only ever reappears, all for the sake of bringing about new people who will in turn only suffer the way we do.

Schopenhauer’s chapter on “The Metaphysics of the Love of the Sexes” in The World as Will and Idea is worth quoting from at length:

This longing, which attaches the idea of endless happiness to the possession of a particular woman, and unutterable pain to the thought that this possession cannot be attained – this longing and this pain cannot obtain their material from the wants of an ephemeral individual; but they are the sighs of the spirit of the species… The species alone has infinite life, and therefore is capable of infinite desires, infinite satisfaction, and infinite pain. But these are here imprisoned in the narrow breast of a mortal. No wonder, then, if such a breast seems like to burst, and can find no expression for the intimations of infinite rapture or infinite misery with which it is filled…

The satisfied passion also leads oftener to unhappiness than to happiness. For its demands often conflict so much with the personal welfare of him who is concerned that they undermine it, because they are incompatible with his other circumstances, and disturb the plan of life built upon them. Nay, not only with external circumstances is love often in contradiction, but even with the lover’s own individuality, for it flings itself upon persons who, apart from the sexual relation, would be hateful, contemptible, and even abhorrent to the lover. But so much more powerful is the will of the species than that of the individual that the lover shuts his eyes to all those qualities which are repellent to him, overlooks all, ignores all, and binds himself for ever to the object of his passion – so entirely is he blinded by that illusion, which vanishes as soon as the will of the species is satisfied, and leaves behind a detested companion for life…

Because the passion depended upon an illusion, which represented that which has only value for the species as valuable for the individual, the deception must vanish after the attainment of the end of the species. The spirit of the species which took possession of the individual sets it free again. Forsaken by this spirit, the individual falls back into its original limitation and narrowness, and sees with wonder that after such a high, heroic, and infinite effort nothing has resulted for its pleasure but what every sexual gratification affords. Contrary to expectation, it finds itself no happier than before. It observes that it has been the dupe of the will of the species. (Haldane and Kemp translation)

Far better to be free of the whole thing, Schopenhauer thought, though he was far from free of it himself. In his introduction to an anthology of Schopenhauer’s essays, R. J. Hollingdale writes of Schopenhauer’s many unromantic sexual encounters:

The strength of his sexual drive was certainly considerable in itself, and when he condemns it as the actual centre and intensest point of the ‘will to live’ he speaks from experience: his fundamental feeling towards it was undoubtedly that he was its victim, that he was ‘in thrall’ to it. In his best recorded moments Schopenhauer understands more vividly than anyone the suffering involved in life and the need felt by all created things for love and sympathy: at these moments he knew and hated the coldness and egoism of his own sensuality. (p. 34)

Naturally, Schopenhauer goes too far. But his excessive pessimism about matters of sex counterbalances the excessive optimism of the age we live in now, which absolutely, foot-stompingly, fingers-in-the-ears refuses to listen even to the mildest criticism of any sexual preference or behavior as long as it is consensual. That our unprecedented hedonism and depravity have given rise to the literal insanity of denying that the distinction between the sexes is objectively real would not have surprised the likes of Plato and Aquinas, and perhaps not Schopenhauer either.

Wagner variations

A philosophy can be profound even when it is ultimately mistaken, and Schopenhauer’s is both. In his essay “On Suicide,” he notes that “Christianity carries in its innermost heart the truth that suffering (the Cross) is the true aim of life.” But Christianity nevertheless insists that “all things [are] very good,” so that suffering serves an “ascetic” purpose in properly orienting us toward the ultimate good that will redeem it. Schopenhauer shares Christianity’s view that suffering is central to human existence and ought to be faced ascetically, but he rejects the thesis that all things are very good. Hence whereas Christian asceticism is motivated by hope, Schopenhauer’s is motivated by despair. But he captures a deep truth in facing up to the reality that if there is no God, despair is the only honest response.

Powerful evidence of the profundity of Schopenhauer’s philosophy is afforded by the influence it famously had on the music of Richard Wagner. (Try to imagine – without laughing – a New Atheist, or even a more serious thinker like Russell or Hume, inspiring such music.)

The Schopenhauerian themes that the will to live that underlies all reality is most powerfully manifest in sexual desire, that lovers’ yearning to melt into one another echoes the oneness of all things underlying the phenomenal world, that the happiness lovers hope for nevertheless cannot be realized, that suffering and death are their inevitable tragic fate – such themes are given palpable expression in Wagner’s sublime Tristan und Isolde,and The Ring bears the mark of Schopenhauer’s influence as well.

This is fitting, since Schopenhauer held that of all forms of expression, music, which operates below the level of the conceptualizations that apply only to the phenomenal realm, best conveys our intuition of the blind will that is the true nature of the world as it is in itself. In any event, a man whose thought could inspire the Liebestod has an undeniable claim to being a great philosopher, and for my money, probably the greatest of atheist philosophers.

October 24, 2021

Untangling the web

David S. Oderberg and others on free speech, in the new anthology

Having Your Say: Threats to Free Speech in the 21st Century

, edited by J. R. Shackleton.

David S. Oderberg and others on free speech, in the new anthology

Having Your Say: Threats to Free Speech in the 21st Century

, edited by J. R. Shackleton. In First Things, William Lane Craig in quest of the historical Adam. Christianity Today interviews Craig about his new book on the subject.

At Rolling Stone, Steely Dan’s Donald Fagen on the release of two live albums and the prospect of a new album. Fagen is interviewed at Varietyand the Tablet. The Ringer on the Dan’s new following among millennials. Elliot Scheiner on engineering Gaucho.

At Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews, Jeffrey Hause reviews Tobias Hoffmann’s book Free Will and the Rebel Angels in Medieval Philosophy.

Michael Huemer is interviewed at What is It Like to Be a Philosopher? Colin McGinn comments on the interview.

At Thomistica, Glen Coughlin on Charles De Koninck on metaphysics and natural philosophy.

The Daily Nous interviews philosopher P. M. S. Hacker.

At City Journal, Blake Smith on Christopher Lasch and Michel Foucault. Michael Behrent on the real Foucault, at Dissent.

The Story of Marvel Studios is now out. The authors are interviewed at Gizmodo. Winter is Coming on five fascinating revelations from the book.

The Guardian on the ideas and controversies of Steven Pinker.

Michael Blastland on William of Ockham, at Prospect.

Joseph M. Bessette and J. Andrew Sinclair on public support for capital punishment, at RealClearPolicy. Their more detailed report is available from the Rose Institute at Claremont McKenna College.

At Public Discourse, Martin Rhonheimer on natural law and the right to private property.

John Whitfield on fraud, bias, negligence, and hype in science, at the London Review of Books.

At American Greatness, Michael Anton on Glenn Ellmers’ new book on Harry Jaffa.

Tad Schmaltz’s book The Metaphysics of the Material World: Suárez, Descartes, Spinoza is reviewed by Alison Peterman at Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews.

Isaac Asimov’s Foundation comes to television. Screen Rant on how the Apple TV series alters the original story.

At National Review, Carrie Gress on feminism and female unhappiness. Scott Yenor calls for a sexual counter-revolution, at First Things.

Economist Philip Pilkington on how demographics could favor Republicans, at Newsweek.

Christopher Wolfe on John Rawls and natural law, at Public Discourse.

At New English Review, Kenneth Francis on the classic 1968 film The Swimmer and the problem of suffering.

At Quillette, philosopher Michael Robillard on the incoherence of gender ideology. Heterodorx interviews philosopher Alex Byrne.

Richard Marshall interviews philosopher Robert Gressis at 3:16.

At Pints with Aquinas, William Lane Craig and Jimmy Akin debate the kalām cosmological argument.

Jazzwise on the life and legend of Thelonious Monk.

From the Thomistic Institute, Fr. Thomas Joseph White lectures on Christ and the Old Testament in Aquinas.

Ruy Teixeira begs his fellow liberals to stop committing “the Fox News Fallacy.” Liberal journalist Kevin Drum argues that it was liberals who started the culture wars. Andrew Sullivan on the Left’s accelerating extremism. A study on political polarization in the journal Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy finds that “the most liberal Democrats [express] the greatest dehumanization of Republicans.” Glenn Greenwald on the increasing prevalence of smear tactics on the Left. Freddie deBoer on the progressives’ politics of personal destruction. At The Atlantic, Sally Satel on left-wing authoritarianism.

But has wokeness finally peaked? Joel Kotkin on the growing backlash, at Spiked. Bari Weiss calls for resistance at Commentary, on CNN, and at UnHerd. Philosopher Arif Ahmed on fighting back against woke censorship at Cambridge. Andrew Sullivan on emerging cracks in the woke elite. Noah Rudnick on the right turn among Latino voters, at City Journal.

At Theology Unleashed, philosopher David Papineau and neurosurgeon Michael Egnor debate materialism.

Terry Teachout on film noir, at Commentary. At Mystery & Suspense, Paul Haddad on film noir and Los Angeles. Terry Gross interviews Eddie Muller about the lost world of film noir at NPR.

October 19, 2021

Truth as a transcendental

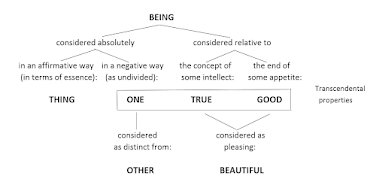

Last June, I presented a talk on the topic “Truth as a Transcendental” at the Aquinas Philosophy Workshop on the theme Aquinas on Knowledge, Truth, and Wisdom in Greenville, South Carolina. You can now listen to the talk at the Thomistic Institute’s Soundcloud page. (What you see above is the chart on the transcendentals referred to in the talk. Click on the image to enlarge. You'll also find a handout for the talk, which includes the chart, at the link to the Soundcloud audio of the talk.)

Edward Feser's Blog

- Edward Feser's profile

- 329 followers