Edward Feser's Blog, page 4

June 16, 2025

Immortal Souls in Religion & Liberty

In the Summer2025 issue of the Acton Institute’s

Religion & Liberty

,David Weinberger kindly reviews my book

Immortal Souls: A Treatise on Human Nature

. From the review: “Feser combines… rigor with histalent for making difficult ideas digestible… An admirable feature of Feser’streatise is how thoroughly he engages opposing positions.”

In the Summer2025 issue of the Acton Institute’s

Religion & Liberty

,David Weinberger kindly reviews my book

Immortal Souls: A Treatise on Human Nature

. From the review: “Feser combines… rigor with histalent for making difficult ideas digestible… An admirable feature of Feser’streatise is how thoroughly he engages opposing positions.”

June 11, 2025

Riots should be suppressed swiftly and harshly

In anarticle at Postliberal Order, Iargue that the Trump administration has the right under natural law tointervene to suppress riots of the kind seen in Los Angeles this week.

In anarticle at Postliberal Order, Iargue that the Trump administration has the right under natural law tointervene to suppress riots of the kind seen in Los Angeles this week.

June 6, 2025

MacIntyre on Hegel on human action

Phrenologywas the pseudoscience that aimed to link psychological traits to the morphologyof the skull. Physiognomy was thepseudoscience that aimed to link such traits to facial features. In his Phenomenologyof Spirit, Hegel critiques these pseudosciences. Since they are now widely acknowledged to bepseudosciences, it might seem that Hegel’s critique can be of historicalinterest only. But as the late AlasdairMacIntyre pointed out in his essay “Hegel: On Faces and Skulls,” Hegel’s mainpoints can be applied to a critique of today’s fashionable attempts to predictpsychological traits and human actions from physiological and genetictraits. (The essay appears in thecollection Philosophy Through Its Past,edited by Ted Honderich.)

Phrenologywas the pseudoscience that aimed to link psychological traits to the morphologyof the skull. Physiognomy was thepseudoscience that aimed to link such traits to facial features. In his Phenomenologyof Spirit, Hegel critiques these pseudosciences. Since they are now widely acknowledged to bepseudosciences, it might seem that Hegel’s critique can be of historicalinterest only. But as the late AlasdairMacIntyre pointed out in his essay “Hegel: On Faces and Skulls,” Hegel’s mainpoints can be applied to a critique of today’s fashionable attempts to predictpsychological traits and human actions from physiological and genetictraits. (The essay appears in thecollection Philosophy Through Its Past,edited by Ted Honderich.)That ideaalone makes Hegel’s arguments worthy of our consideration. For it would certainly be of interest if itturned out that the fundamental problems with pseudosciences like phrenologyand physiognomy had to do, not with their inadequacies vis-à-vis the empiricalevidence, but with deeper philosophical assumptions they share with purportedlymore empirically plausible and respectable versions of materialistreductionism. The arguments are not,however, presented with maximal crispness. But they are suggestive and worth trying to tease out. What follows is an attempt to do so (and itsfocus is on Hegel as MacIntyre reads him rather than on Hegel’s own texts).

The appeal to the past

MacIntyrenotes several ways in which Hegel takes there to be a mismatch between brute anatomicaland physiological facts on the one hand, and human thought and action on theother. But it seems to me that there aretwo main lines of argument identified by MacIntyre. The first, as I understand it, goes likethis. Scientific explanations, includingphysiological explanations, appeal to general propositions, such aspropositions of the form “For every x, if x is F then x is G.” For example, we might explain why aparticular glass of water froze by saying “For every x, if x is water then xwill freeze at 32 degrees Fahrenheit.” Our predicates F and G refer to universals, and we explain theparticular phenomenon by simply noting that it is an instance of a completelygeneral truth.

However,Hegel argues, human actions cannot be understood in this way. Suppose, for example (mine, not Hegel’s orMacIntyre’s), that you have a fight with your brother over some longstandinggrudge between the two of you. Properlyto explain this event requires reference to particular earlier events in yourhistory, such as a promise to you that he once broke, or an occasion when youpublicly insulted and embarrassed him. And those events will in turn be explicable in terms of yet other andearlier particular events. Understandingthe character of these events will also involve attention to a variety of contextualdetails, such as who exactly was present on the occasion you publicly insultedhim, and exactly what it was he had promised to do and why it was significant. Furthermore, it will involve attention to howall the relevant parties conceived ofthese various details.

Thesecircumstances, thinks Hegel (as presented by MacIntyre) simply cannot becaptured in general propositions of the kind to which scientific explanationsappeal. In particular, there are no truegeneralizations to the effect of “For every x and every y, if x and y arebrothers and x breaks a promise to y, then x and y will get in a fight severalyears later” (or whatever). What makesthe sequence of events intelligible, in Hegel’s view, is not that it is aparticular instance of a general pattern, where all events of the one kind willbe followed by events of the other. Rather, that you acted in light of certain particular, contingent historical circumstances is an ineliminableaspect of the story, and cannot be captured in general or lawlikepropositions. You are responding to those circumstances qua particular, notto just any old circumstances that happened to be of that general type. As MacIntyre writes, “to respond to aparticular situation, event, or state of affairs is not to respond to any situation,event, or state of affairs with the same or similar properties in some respect;it is to respond to that situation conceivedby both the agents who respond to it and those whose actions constitute it asparticular” (p. 329).

What shouldwe think of this argument? I’m notsure. Certainly it would need muchtightening up before it could be judged compelling. However, it does seem to be at least in thegeneral ballpark of arguments that I think are powerful. For example, it is reminiscent of DonaldDavidson’s famous principleof the anomalism of the mental, according to which there can be nostrict laws by which mental events might be predicted and explained. (Though Davidson’s argument too needstightening up.)

The appeal to the future

What seemsto me to be a second, distinct Hegelian argument discussed by MacIntyre (albeitnot characterized by him as such) is expressed in this passage:

From the fact that an agent has a given trait, we cannot deduce what he will do in any givensituation, and the trait cannot itself be specified in terms of somedeterminate set of actions that it will produce… [T]he crucial fact aboutself-consciousness… is, its self-negating quality: being aware of what I am isconceptually inseparable from confronting what I am not but could become. Hence, for a self-conscious agent to have atrait is for that agent to be confronted by an indefinitely large set ofpossibilities of developing, modifying, or abolishing that trait. Action springs not from fixed and determinatedispositions, but from the confrontation in consciousness of what I am by whatI am not. (p. 331)

The ideahere seems to be that to be conscious of oneself as an agent is, of its nature,precisely to be conscious of the possibility of an indefinite number ofalternative choices. By contrast, tounderstand an anatomical or physiological feature is to know it as limited to acertain specific and relatively narrower range of effects in might have. Whereas, in Hegel’s first argument, the ideais that a reductionist physiological explanation cannot account for thesignificance of one’s past, in this argument the idea is that it cannot accountfor the openness of one’s future.

To make thepoint a little clearer, consider this passage from earlier in MacIntyre’sessay:

The relation of external appearance, including the facialappearance, to character is such that the discovery that any externalappearance is taken to be a sign of a certain type of character is a discoverythat the agent may then exploit to conceal his character. (p. 325)

The pointhere seems to be this. Suppose someonetold me that he could, from my facial expressions, read off my character andthus predict my future actions. Knowingthis, I could make sure that in the future I avoid the facial expressions Iwould otherwise normally be inclined toward, so that my interlocutor will bethrown off and his predictions will fail. Similarly, suppose someone told me that, based on what he had determinedfrom scanning my brain, he predicted that I would make a cup of coffee in thenext half hour. Even if I were inclinedto do so, I could now choose otherwise simply to prove him wrong. There’s an openness to alternative possibilitiesin the behavior of human beings that differentiates them from the rigidbehavior of merely physical systems, including those that comprise the micro-levelparts of human beings considered in isolation from the whole.

This line ofthought calls to mind the similar argumentdeveloped by Jean-Paul Sartre in Beingand Nothingness. He famously draws adistinction there between being-in-itselfand being-for-itself. Being-in-itself is the kind of reality had bya mere physical object as it exists objectively or independently of human consciousness. It is simply given or fixed. By contrast, being-for-itself, which is thehuman agent, is consciousness as it projects forward toward an unrealizedpossibility. Unlike being-in-itself, itis open to different possibilities rather than entirely fixed or determined. To deny free will is essentially to conflatebeing-for-itself with being-in-itself, but this cannot be done, because theyare simply irreducibly different. Naturally,Sartre’s argument, and Hegel’s too, would require tightening up if we are to makethem compelling.

Now, thegeneral idea that the conceptual and logical structure of thought are simplyirreducibly different from, and inexplicable in terms of, any collection ofphysical facts and their causal relations, is something I defend rigorously andat length in chapters 8 and 9 of my book ImmortalSouls. I take it that Hegel’sfirst argument is aiming at something like that conclusion. And the general idea that human action isirreducibly teleological, and in particular that it cannot be analyzed in termsof efficient-causal relations (of the kind that obtain between physiologicalphenomena, for example) is something I defend in depth in chapter 4 of thebook. I take it that Hegel’s secondargument is aiming at something like that conclusion.

Hence I am,in a very general way, sympathetic at least to the basic idea of the kind ofposition MacIntyre attributes to Hegel. I leave as a homework exercise the question whether there are, in thatposition, ingredients for a line of argument that is both compelling and independentof considerations of the kind I set out in the book.

May 30, 2025

Lamont on Trump, abortion, and Ukraine

In anarticle at One Peter Five,philosopher John Lamont warns his fellow Catholics and traditionalists that on issuessuch as abortion and Russia’s war of aggression in Ukraine, Trump is not an ally and must beresisted.

In anarticle at One Peter Five,philosopher John Lamont warns his fellow Catholics and traditionalists that on issuessuch as abortion and Russia’s war of aggression in Ukraine, Trump is not an ally and must beresisted.

What is ideology?

What doesthe pejorative use of “ideology” amount to, and what is it to be an “ideologue”? I consider some common accounts beforedeveloping my own in my latest essay atPostliberal Order.

What doesthe pejorative use of “ideology” amount to, and what is it to be an “ideologue”? I consider some common accounts beforedeveloping my own in my latest essay atPostliberal Order.

May 22, 2025

Alasdair MacIntyre (1929-2025)

AlasdairMacIntyre has died. His classic AfterVirtue had a tremendous effect on me when I was an undergrad and still inmy atheist days, greatly reinforcing the attraction to Aristotelian ethics Ihad even then. (The spine of the light mauve cover of my copy, like that of prettymuch any copy printed in the 80s, has long since turned green.) It was, of course, part of a larger body ofwork which had a similarly great impact on so many people, in philosophy, theology,and beyond. RIP.

AlasdairMacIntyre has died. His classic AfterVirtue had a tremendous effect on me when I was an undergrad and still inmy atheist days, greatly reinforcing the attraction to Aristotelian ethics Ihad even then. (The spine of the light mauve cover of my copy, like that of prettymuch any copy printed in the 80s, has long since turned green.) It was, of course, part of a larger body ofwork which had a similarly great impact on so many people, in philosophy, theology,and beyond. RIP.

May 17, 2025

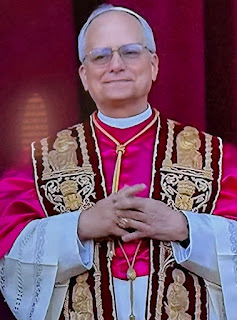

Pope Leo XIV on families and the family of nations

Yesterday,Pope Leo XIV delivered an addressto the diplomatic corps at the Vatican. It was brief and very simple, butelegant and deep and shows the influence of his namesake Leo XIII and of histheological guide St. Augustine. Theworld, Leo says, is a “family of peoples.” And essential to the wellbeing of nations and the family of nations, hesays, are peace, justice, and truth, wherepeace has justice and truth as its preconditions. The talk is devoted to elaborating on thesethree themes. What follows are somecomments on Leo’s remarks.

Yesterday,Pope Leo XIV delivered an addressto the diplomatic corps at the Vatican. It was brief and very simple, butelegant and deep and shows the influence of his namesake Leo XIII and of histheological guide St. Augustine. Theworld, Leo says, is a “family of peoples.” And essential to the wellbeing of nations and the family of nations, hesays, are peace, justice, and truth, wherepeace has justice and truth as its preconditions. The talk is devoted to elaborating on thesethree themes. What follows are somecomments on Leo’s remarks.Peace, Leonotes, is not merely a negative condition, namely the absence of conflict. True peace between people has as a positive preconditiona purity of heart that entails freedom from pride and vindictiveness, and awill to cooperate and understand rather than to conquer. Here there is an echo of Augustine’s famousaccount of peace as “the tranquility of order,” where order involves a unity ofpurpose. Peace in a community requiresagreement on an end, and for Augustine it must be the right end. What end is that? For Augustine it is God, and significantly,Leo remarks that “peace is first and foremost a gift. It is the first gift of Christ.” (I have more to say about Augustine’s accountof peace in arecent Postliberal Order article.)

Turning tojustice, Leo indicates that this too requires well-ordered societies. In this connection, he calls attention to LeoXIII’s famous social encyclical RerumNovarum. Importantly, while hementions working conditions, poverty, and the like, his emphasis is on somethingelse. He says:

It is the responsibility of government leaders to work tobuild harmonious and peaceful civil societies. This can be achieved above all by investing inthe family, founded upon the stable union between a man and a woman, “a smallbut genuine society, and prior to all civil society.” In addition, no one is exempted from strivingto ensure respect for the dignity of every person, especially the most frailand vulnerable, from the unborn to the elderly, from the sick to theunemployed, citizens and immigrants alike.

The phrasein quotation marks is from Rerum Novarum,and it is the one direct quote from that document. Like Leo XIII and other popes who have setout Catholic social teaching, Leo emphasizes that the health of the family is the fundamental precondition of thehealth of society, and that seeing to the health of the family is one of theduties of governing officials.

This basictruth of Catholic social teaching is radically at odds with long-prevailingattitudes on both the political left and the political right. Both, in their different ways, wrongly insiston emphasizing economics rather than morality and culture when addressingsocial problems. Both have essentiallyendorsed the sexual revolution and its transformation in attitudes aboutdivorce, extramarital sex, homosexuality, and the like, albeit the right hasdone so in a more gradual, piecemeal, and in some cases reluctant manner. And both have now essentially adopted thelibertarian position that even if one laments the sexual revolution, governmenthas no place in trying to roll it back. Fromthe point of view of Catholic social doctrine, true social justice cannot beachieved until we at long last abandon these errors.

On the topicof truth, Leo says:

Where words take on ambiguous and ambivalent connotations,and the virtual world, with its altered perception of reality, takes overunchecked, it is difficult to build authentic relationships, since theobjective and real premises of communication are lacking. For her part, the Church can never beexempted from speaking the truth about humanity and the world, resortingwhenever necessary to blunt language that may initially createmisunderstanding.

Though earlierin his address, he had also called for “carefully choosing our words. For words too, not only weapons, can wound andeven kill.”

Leo’s pointhere seems to be, first, that one obstacle to truth prevailing in humanrelationships today is the degree to which people’s perceptions are shaped bythe “virtual world” – social media and the like, with the biases, groupthink, hottakes, and emotion-driven commentary that it fosters. This virtual world is reminiscent of theshadows on the wall of Plato’s cave, which radically distort the understandingof those who dwell in it.

Anotherobstacle to truth, Leo indicates, is the way that language is so often usedtoday as a weapon or a means of obfuscation, rather than a means ofcommunicating for the sake of mutual understanding and describing objectivereality. Hence the tendency ofpoliticians to use words to flummox opponents, rile up allies, and keepcitizens perpetually off balance and divided; and of ideologues to introducenovel usages so as to lend false plausibility to rank sophistries (think of theviolence done to language by gender theory, for example).

Leo teachesthat we must remain grounded in objective reality and insist on using languageto convey that reality, even bluntly wherever necessary. This, he goes on to say, is what charityrequires, for genuine unity between people must be grounded in truth. And ultimately, he also says, “truth is notthe affirmation of abstract and disembodied principles, but an encounter withthe person of Christ himself, alive in the midst of the community of believers.”

Thisemphasis on truth as ultimately Christocentric once again echoesAugustine. It also once again echoes LeoXIII, who in Rerum Novarum not onlyemphasizes that getting the family right is a basic precondition of social justice,but also that, even more fundamentally, “no satisfactory solution will be foundunless religion and the Church have been called upon to aid.” As Leo XIII went on to say in that grand encyclical:

Without hesitation We affirm that if the Church isdisregarded, human striving will be in vain… And since religion alone, as Wesaid in the beginning, can remove the evil, root and branch, let all reflectupon this: First and foremost Christian morals must be reestablished, withoutwhich even the weapons of prudence, which are considered especially effective,will be of no avail, to secure well-being.

One lastremark about Leo XIV’s address. Hisphrase “family of peoples” is, I think, especially apt today as an implicit correctionto two opposite extreme errors found on the opposite sides of the politicalspectrum. On the left we find aglobalism that tends to dissolve borders and treats national loyalties as ifthey are somehow inherently suspect. On theright we find a jingoistic bellicosity that overcorrects for thisglobalism. To see the world as a familyof peoples is to see what is wrong with both of these extremes. For distinct peoples have a right to preservewhat defines them as a people, culturally, linguistically, and economically. But a good member of a family of peoples doesnot bully or intimidate or lord it over other family members.

May 8, 2025

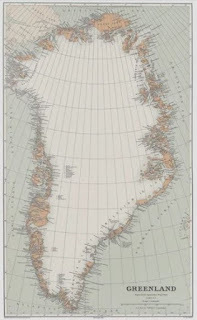

Greenland and the ethics of annexation

PresidentTrump has repeatedly called for U.S. acquisition of Greenland. The motivations haveto do with Greenland’s strategic location and access to its mineralreserves. Neitherthe government of Denmark (of which Greenland is a territory), northe people of Greenland themselves, are in favor of the idea. Not only is Trump undeterred by those facts,he has repeatedly refused to rule out the possibility of using military forceto annex the island. For example, inJanuary, when asked whether he could assure the world that he would not resortto military coercion to get control of Greenland, Trumpreplied “No, I can’t assure you” and “I’m not going to commit tothat.” Asked this month about usingmilitary force to take Greenland, Trump saidthat “it could happen, something could happen with Greenland” and “I don’t ruleit out.”

PresidentTrump has repeatedly called for U.S. acquisition of Greenland. The motivations haveto do with Greenland’s strategic location and access to its mineralreserves. Neitherthe government of Denmark (of which Greenland is a territory), northe people of Greenland themselves, are in favor of the idea. Not only is Trump undeterred by those facts,he has repeatedly refused to rule out the possibility of using military forceto annex the island. For example, inJanuary, when asked whether he could assure the world that he would not resortto military coercion to get control of Greenland, Trumpreplied “No, I can’t assure you” and “I’m not going to commit tothat.” Asked this month about usingmilitary force to take Greenland, Trump saidthat “it could happen, something could happen with Greenland” and “I don’t ruleit out.”However,such military action would be manifestly contrary to the criteria oftraditional just war theory. And even ifthe threat is intended merely as a negotiating tactic (as is likely), it wouldbe contrary to the natural law principles governing internationalrelations. These facts should be obviousto all, and would have been until recently. But Trump’s most ardent supporters have an alarming tendency reflexivelyto defend even the most outrageous things he does, cobbling together feeble rationalizationsfor words and actions they would condemn had they come from anyone else. It is worthwhile, then, to set out thereasons why Trump’s statements regarding Greenland are indefensible.

Greenland annexation and just warcriteria

Again, militaryaction to annex Greenland would clearly be unjust. For it manifestly would not meet the “justcause” criterion of just war theory. Onecountry can justly make war on another only when the other country is guilty ofsome rights violation grave enough for war to be a proportionate response. The most obvious example would be when acountry goes to war in order to repel an aggressor. But neither Denmark nor Greenland is guiltyof aggressing against the United States, or of any other violation of U.S.rights. Indeed, they are longtime alliesof the U.S.

The factthat the United States would find Greenland’s location and resources useful forpurposes of defense is irrelevant. If Iwould find it useful to take over my neighbor’s property in order to protect myown against robbers, that hardly gives me a right to do so. Indeed, it would make me a robber. Nor will it doto pretend that governments are somehow not bound by the same moral prohibitionagainst robbery that binds individuals. As St. Thomas Aquinas writes:

As regards princes, the public power is entrusted to themthat they may be the guardians of justice: hence it is unlawful for them to useviolence or coercion, save within the bounds of justice... To take otherpeople's property violently and against justice, in the exercise of public authority,is to act unlawfully and to be guilty of robbery. (Summa Theologiae II-II.66.8)

Theinjustice of wars of territorial expansion is not a matter of controversy amongnatural law theorists in the Thomistic tradition, but has long been thestandard position. For example, ThomasHiggins’s Man as Man: The Science and Artof Ethics says that “war of aggression is the violent endeavor to depriveanother people of independence, territory, or the like, for the sake ofincreasing one’s own power and prestige… The Natural Law forbids all wars ofaggression” (p. 543). Austin Fagothey’s Right and Reason notes that “territorialaggrandizement, glory and renown, envy of a neighbor’s possessions,apprehension of a growing rival, maintenance of the balance of power… these andthe like are invalid reasons” for going to war (p. 564). Fagothey also notes that though it can undercertain circumstances be licit for a country to acquire new land, this wouldnot be true of “land… recognized as the territory of an existing state,” andthat “an existing state may not be deprived of its territory” (p. 547).

The seriousnessof these points cannot be overstated. Theproblem is not just that the forced annexation of Greenland would amount to robberyon a massive scale. It is that, becauseit would result in deaths, such an unjust military action would be tantamountto murder. It would make the president awar criminal. It would be a massiveinjustice not only against the people of Greenland, but also against theAmerican military, which Trump would be making an instrument of suchcriminality.

A negotiating tactic?

Many ofTrump’s defenders would say that he isn’t serious about resorting to militaryforce, but merely intends such rhetoric as a negotiating tactic. It is no doubt true that he intends it thatway. It is also likely true that, at theend of the day, he would refrain from using such force, if only because thepolitical costs would be too great.

It issignificant, though, that in Trump’s most recent remarks, he seemed to draw adistinction between the situation with Greenland and the situation with Canada,which he has repeatedly said also ought to become part of the UnitedStates. Asked about the possibility ofusing military force to acquire Canada, Trump said: “Well, I think we're not goingto ever get to that point” and “I don’t see it with Canada, I just don’t seeit.” That is hardly an acknowledgementthat acquiring Canada in such a way would be wrong, and thus to be ruled out absolutely. It sounds more like a judgment to the effectthat attacking Canada would merely be unnecessary or impractical. But his answer in the case of Greenland isdifferent. Again, he said that “it couldhappen, something could happen with Greenland” and “I don’t rule it out,” evenif he also says that that too is unlikely. Overall, his remarks give the impression that he does indeed regardmilitary action against Greenland as at least remotely possible. There is also the fact that theadministration hasnow stepped up intelligence operations vis-à-vis Greenland.

In anyevent, even if this rhetoric is meant as a negotiating tactic, it is stillgravely immoral. There are at least twoways that the refusal to rule out military action could function as anegotiating tactic. Trump mightgenuinely intend to keep the option openin order to frighten Denmark and Greenland into making a deal, even if he doesnot currently have any plan actually to resort to such action. Or he might merely be bluffing in order to frighten them into making a deal, but wouldnot ever really carry out such action. Either of these tactics would be gravely wrong, though not in the sameway.

John Finnis,Joseph Boyle, and Germain Grisez discuss the difference between genuinelykeeping an option open and merely bluffing in their book Nuclear Deterrence, Morality, and Realism,and some of the points they make are relevant to the present topic.

Consider thefirst possibility, that Trump intends to keep open the option of takingmilitary action against Greenland, but also hopes and believes that he willnever have to carry this threat out. AsFinnis, Boyle, and Grisez point out, it is a fallacy to suppose that if someonehopes and believes he never has to carry out a threat to do some action, thenit follows that he does not really intend that action. The reality is rather that “people whofortunately avoid what they only reluctantly intend, or who might have a changeof mind in the future, are people whose minds are now made up” (pp.104-5). In the present case, if Trumpreally does want to keep the option open, then he does in the relevant sensehave the intention of taking military action against Greenland if he cannot otherwise acquire it. That remains the case even if he also hopesand believes he will be able to acquire it peacefully.

But as wehave seen, acquiring Greenland this way would violate just war criteria, andthus amount to murder. As Finnis, Boyle,and Grisez write of keeping open the option of carrying out a murderous act:

It would be doubly conditioned – conditional not only on anadversary’s act in defiance of the threat, but on a choice still to be made toexecute it. None the less, that doublyconditioned intention would still be a murderous will. If one intends now to be in a position tocommit murder, should one later decide that the situation warrants it, theneven now one is willing (however reluctantly) to murder. (p. 111)

So, keepingopen the option of taking military action against Greenland, even if intendedjust as a negotiating tactic, is still tantamount to an intention to murder,and is thus gravely immoral. Considerthen the alternative scenario, on which Trump is merely bluffing. On this hypothesis, Trump does not in fact intend even to keep themilitary option open. He simply wantsDenmark and Greenland to think thathe is keeping it open. Even if this iswhat is going on, it is still gravely immoral for at least three reasons, thefirst two of which are set out by Finnis, Boyle, and Grisez.

First, whena country threatens an immoral military action, it is not only the intentionsof its leaders that are morally relevant. Also relevant are the intentions of everyone else in some way connectedto the action, from soldiers to ordinary citizens. In the present case, even if Trump himself isbluffing, the bluff can only work if it is not obviously a bluff – that is to say, if a critical mass of peoplethink he really might carry out the threat. And that will lead at least some people (government officials, militarypersonnel, and voters) to decide to support the action if he carries itout. That is to say, they will form theintention of supporting a murderous action. They will not be bluffing,even if Trump is. And as Finnis, Boyle,and Grisez write: “Those who deliberately bring others to will what is evilmake themselves guilty, not only of the evil the others will, but also ofleading them to become persons of evil will” (p. 119). In the case at hand, such a leader “would beinciting the others to intend to kill the innocent” (p. 120), even if he doesnot himself really intend to do so.

Second, itis not just what individuals do or will that is relevant. The military actions of a country are social acts, acts carried out by thesociety as a whole (understood as what is traditionally called a kind of “corporateperson” or “moral person”). As Finnis, Boyle, and Grisez note, a teamcan rightly be said to intend to win a game, even if certain individual members of the team do not intend thisbut would rather lose. Similarly, evenif a president is personally bluffingwhen he makes a threat, it doesn’t follow that the communal act of the United States as a country, inmaking the threat, amounts to a bluff. The reason is that “the social act… is defined by its public proposal” rather than by whatthis or that individual might privately think, “and that proposal is not aproposal to bluff” (pp. 122-23, emphasis added).

Extorted contracts are immoral

The thirdproblem is this. Even if Trump is merelybluffing, the point of the bluff would be to frighten Denmark and Greenlandinto making an agreement they would not otherwise be willing to make. But this is sheer extortion andgangsterism. Moral common sense andtraditional natural law theory alike hold that an agreement cannot be licit orbinding if made under such unjust duress. As one standard manual of moral theology puts it:

The defects that vitiate consent by taking away knowledge orchoice render contracts either void or voidable. These impediments [include]… fear, which is a disturbance of mindcaused by the belief that some danger is impending on oneself or others… [and] violence or coercion, which is like to fear, the latter being moral force andthe former physical force. (John McHugh and Charles Callan, Moral Theology, Vol. II, pp. 140-41)

To be sure,the reference here is to contracts between individuals, but natural law theoristsstandardly hold that, mutatis mutandis,what is true for agreements between individuals is true for treaties betweennations. As Fagothey writes, “theconditions for a valid treaty are the same as those for any valid contract,” sothat “if an unjust aggressor is victorious, the treaty he imposes is unjust andtherefore invalid” (Right and Reason,pp. 549-50). And as another natural lawtheorist says, “a treaty made under duress, say, made under threat of war… canhardly be regarded as binding, or at least should be regarded as rescindible,if the conditions imposed are manifestly and flagrantly unjust” (MichaelCronin, The Science of Ethics, Vol.II, p. 658).

It is nodefense of the president’s comments, then, to say that they are meant as anegotiating tactic rather than seriously evincing an intention to go towar. For a negotiating tactic of thiskind is itself also gravely immoral.

Pope Leo XIV

Let us prayfor our new pope, Leo XIV. His choices to take atraditional name and to appear in traditional papal garb (as Benedict XVI didand Francis did not) are small but encouraging signs of a man who subordinateshimself to the papal office and understands the importance of continuity withthe past.

Let us prayfor our new pope, Leo XIV. His choices to take atraditional name and to appear in traditional papal garb (as Benedict XVI didand Francis did not) are small but encouraging signs of a man who subordinateshimself to the papal office and understands the importance of continuity withthe past.

April 28, 2025

The ethics of wealth and poverty

In my latest essay at Postliberal Order, I discuss whatChrist, the Fathers of the Church, and Aristotle have to say about the moralhazards of riches.

In my latest essay at Postliberal Order, I discuss whatChrist, the Fathers of the Church, and Aristotle have to say about the moralhazards of riches.

Edward Feser's Blog

- Edward Feser's profile

- 334 followers