Edward Feser's Blog, page 3

July 24, 2025

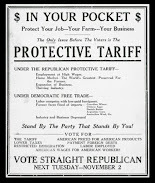

A postliberal middle ground on trade

In my latestarticle at Postliberal Order, Idefend a postliberal middle ground position on tariffs and other aspects of trade policythat avoids both the errors of classical liberalism and a rigid protectionism.

In my latestarticle at Postliberal Order, Idefend a postliberal middle ground position on tariffs and other aspects of trade policythat avoids both the errors of classical liberalism and a rigid protectionism.

July 19, 2025

Heeding Anscombe on just war doctrine

ElizabethAnscombe’s “Warand Murder” is a magnificent essay, an intellectually rigorous andmorally serious defense of traditional Christian and natural law teachingagainst pacifists on the one side and, on the other, those who attempt torationalize the unjust killing of civilians. As she argues, both errors feed off of one another. The essay is perhaps even more relevant todaythan it was at the time she wrote it.

ElizabethAnscombe’s “Warand Murder” is a magnificent essay, an intellectually rigorous andmorally serious defense of traditional Christian and natural law teachingagainst pacifists on the one side and, on the other, those who attempt torationalize the unjust killing of civilians. As she argues, both errors feed off of one another. The essay is perhaps even more relevant todaythan it was at the time she wrote it.Here is asummary of her position. The pacifistholds that all killing is immoral,even when necessary to protect citizens against criminal evildoers within anation, or foreign adversaries without. This position is contrary to the basic precondition of any social order,which is the right to protect itself against attempts to destroy it. It also has no warrant in the orthodox Christiantradition. A less extreme but relatederror is the thesis that violence can never justly be initiated, but at mostcan only ever be justified in response to those who have initiated it. In fact, Anscombe argues, what matters is notwho strikes the first blow, but who is in the right. For example, it was in her judgment right forthe British to initiate violence in order to suppress chattel slavery.

That is oneset of errors. But another and oppositeextreme error is to abuse the principle that war can sometimes be justifiable,in order to try to rationalize violence that is in fact unjust. Indeed, this opposite extreme is, inAnscombe’s view, the more common error. Andit is more common in war than in police activity, because war affords more occasionsfor the evil of killing the innocent, and civilians in particular. The principle of double effect is too oftenmisapplied in attempts to rationalize such killing.

Having givena general description of these two sorts of error, Anscombe then goes on toexamine each in more detail. Shesuggests that in the early twentieth century, some were drawn to pacifism inpart as an overreaction to universal conscription (which she regards as anevil). But her main focus is on thetheme that pacifism derives from a distortion of Christianity. In part this has to do with a hostility tothe ethos of the Old Testament, which she argues is widely misunderstood andwidely and wrongly thought to be at odds with the New Testament. But the New Testament too has been badlymisunderstood. For example, counsels towhich only some are called (such asgiving away one’s worldly goods) are sometimes misrepresented as preceptsbinding on all.

“The truthabout Christianity,” Anscombe says, “is that it is a severe and practicablereligion, not a beautifully ideal but impracticable one” (p. 48). But the distortions she describes have madeChristianity seem to be an ideal butimpracticable one. And the attractionsome Christians have for pacifism is an example. Many Christians and non-Christians alikebelieve the falsehood that Christ calls us all to pacifism. And because no society could survive if itpracticed pacifism, many thus conclude that Christian morality is simply notpractical.

Here, asAnscombe argues, is where pacifism inadvertently paves the way for those whorationalize the murder of the innocent. Falselysupposing that all violence is eviland also noting that violence is necessary to preserve a society againstevildoers, they take the short step to the conclusion that “committed to‘compromise with evil,’ one must go the whole hog and wage war à outrance” (p. 48). In other words, once we are convinced thatwe’re going to have to do evil anyway in order to protect society, there’s nolimit to the evil we will rationalize as necessary to achieve this goodend. Unrealistic moralizing has as itssequel an amoral realpolitik, falselypresenting itself as the only alternative.

WithCatholics, Anscombe says, this amorality masquerades as an application of theprinciple of double effect. True, thisprinciple can indeed in some cases justify actions that foreseeably risk harmto civilians, when that harm is not intended and when it is not out ofproportion to the good to be achieved. (For example, it can be justifiable to bomb an enemy military base evenif one foresees, while not intending, that some civilians nearby could bekilled as a result.)

The trouble,Anscombe says, is that people often play fast and loose with the notion of“intention” in order to abuse the principle of double effect. For example, it would be sheer sophistry foran employee to say that when he helped his boss embezzle from the company, his“intention” was not really to assistin embezzlement, but only to avoid getting fired, so that the action could bejustified by double effect. Similarly,Anscombe argues, it is sophistry to pretend that the obliteration bombing ofcities does not involve any intentional killing of civilians, but only theintention to end a war earlier. Anothersophistry involves interpreting what counts as a “combatant” very broadly, soas to try to justify attacks on the civilian population in general. Anscombe also responds to various other attemptsto rationalize violations of just war criteria.

That, again,is the argument in outline. Here aresome ways it is relevant today. We have,on the one hand, some Catholics who appear at least to flirt with pacifism. Pope Francis said things that implied thatwar could never be just and that traditional teaching on this matter needed tobe rethought, though healso said things that pointed in the other direction. As with other topics, his teaching on thismatter was simply muddled rather than a clear departure from tradition. But it was muddled in a way that gives aidand comfort to the first, pacifistic erroneous extreme identified by Anscombe.

On the otherhand, we also have many who go to the opposite extreme criticized by Anscombe,of trying to rationalize unjust harm to civilian populations by abuse of theprinciple of double effect and related sophistries. For example, this is the case with much ofthe commentary on Israel’s war in Gaza. Israelcertainly had the right and indeed the duty to retaliate for the diabolicalHamas attack of October 7, 2023, which killed almost 1,200 people. But many seem to think that this gives Israela blank check to do whatever it likes in Gaza, or at least whatever it likesshort of deliberately targeting civilians.

That is notthe case. Yes, traditional just war doctrineholds that it is always immoral deliberately to kill civilians. But that is by no means all that it says onthe matter. It also holds that it isimmoral deliberately to destroy civilian property and infrastructure, andthereby to make normal civilian life impossible. To be sure, it holds too that it can, by theprinciple of double effect, sometimes be permissible to carry out militaryactions that put civilian lives and property at risk, where such risk is not intended but simply foreseen. But it also holds that this harm must not be out of proportion to thegood that one hopes to secure by way of such military action.

ThroughoutGaza, however, civilian property and infrastructure have been largely destroyed,and ordinary life made impossible. The resultinghumanitarian crisis has been steadily worsening. Casualty numbers in Gaza are hotly disputed,but they are undeniably high. According toa recent report:

Almost 84,000 people died in Gaza between October 2023 andearly January 2025 as a result of the Hamas-Israel war, estimates the firstindependent survey of deaths. More thanhalf of the people killed were women aged 18-64, children or people over 65,reports the study.

Suppose for thesake of argument that the true number is half of that, or even just one thirdof that. That would still be extremelyhigh. Such loss of life, destruction ofbasic infrastructure, and making of ordinary civilian life impossible are outof proportion to the evil Israel is retaliating against. And this is putting aside the awfulconditions under which Gazans have been living for years, and the allegationsof cases where civilians have been deliberately targeted during the currentwar. These too are hotly disputedmatters, but the point is that even if wedon’t factor them in, Israeli action in Gaza seems clearly disproportionateand thus not justifiable by the principle of double effect.

There isalso the sophistry some commit of pretending that if a civilian sympathizeswith Hamas, he is morally on a par with a combatant and may be treated as such. And then there is the proposal somehave made to dispossess the Gazans altogether, which would only add a further,massive layer of injustice.

None of thiscan facilitate a long-term solution to the Israel-Palestine problem, but will inevitablygreatly inflame further already high hostility against Israel. A commitment to preserving the basic preconditionsof ordinary civilian life for Israelisand Palestinians alike is both morally required by just war criteria, and aprecondition to any workable modus vivendi.

July 11, 2025

A second Honorius?

Like hispredecessor Honorius, Pope Francis failed clearly to uphold traditionalteaching at a time the Church was sick from heresy. So I argue in my contributionto a symposium on Francis in the latest issue of

The Lamp

.

Like hispredecessor Honorius, Pope Francis failed clearly to uphold traditionalteaching at a time the Church was sick from heresy. So I argue in my contributionto a symposium on Francis in the latest issue of

The Lamp

.

July 10, 2025

Aquinas and prudential judgment

Incontemporary debates in Catholic moral theology, a distinction is often drawnbetween actions that are flatly ruled out in principle and those whosepermissibility or impermissibility is a matter of prudential judgment. For example, it is often noted that abortionis wrong always and in principle, whereas how many immigrants a country oughtto allow in and under what conditions are matters of prudential judgment. But exactly what does this mean, and how dowe tell the difference between the cases?

Incontemporary debates in Catholic moral theology, a distinction is often drawnbetween actions that are flatly ruled out in principle and those whosepermissibility or impermissibility is a matter of prudential judgment. For example, it is often noted that abortionis wrong always and in principle, whereas how many immigrants a country oughtto allow in and under what conditions are matters of prudential judgment. But exactly what does this mean, and how dowe tell the difference between the cases?It isimportant at the outset to put aside some common misunderstandings. The difference between matters of principleand matters of prudential judgment is nota difference between moral questions and merely pragmatic ones. Morality is at issue in both cases. Prudence is,after all, one of the cardinal moral virtues. One can be mistaken in one’s prudential judgments, and when one is, oneis guilty of imprudence, which is a kind of moral failure (whether or not oneis culpable for the failure).

Contrary toanother misunderstanding (which I recently had occasionto rebut), to say that something is a matter of prudential judgmentand then go on to note that reasonable people can differ in their prudentialjudgments is not to commit oneself toany kind of moral relativism. Prudentialjudgments can indeed simply be mistaken. To say that reasonable people can disagree is merely to note that aperson might have made such a judgment in good faith on the basis of theevidence available to him, even if the evidence later turns out to bemisleading or his reasoning turns out to have been flawed. He is still objectively wrong all the same. Or there may in some cases be more than onereasonable way to apply a certain objective and universal moral principle, sothat reasonable people might opt to apply it in any of these different ways.

As always,illumination can be found in St. Thomas Aquinas. In several places, he makes remarks that arerelevant to understanding the difference between straightforward matters ofprinciple and matters of prudential judgment. For example, in On Evil,Aquinas notes:

The will of a rational creature is obliged to be subject toGod, but this is achieved by affirmative and negative precepts, of which thenegative precepts oblige always and on all occasions, and the affirmativeprecepts oblige always but not on every occasion… One sins mortally whodishonors God by transgressing a negative precept or not fulfilling an affirmativeprecept on an occasion when it obliges. (Question VI, Regan translation)

Though thedistinction between matters of principle and matters of prudence is somewhatloose, it seems largely (though perhaps not always) to correspond to Aquinas’sdistinction between negative precepts, which oblige on every occasion, andaffirmative precepts, which do not. Whatthis distinction amounts to is madeclearer in some remarks St. Thomas makes when commenting on St. Paul’s Epistleto the Romans:

He lists the negative precepts, which forbid a person to doevil to his neighbor. And this for tworeasons. First, because the negativeprecepts are more universal both as to time and as to persons. As to time, because the negative preceptsoblige always and at every moment. Forthere is no time when one may steal or commit adultery. Affirmative precepts, on the other hand,oblige always but not at every moment, but at certain times and places: for aman is not obliged to honor his parents every minute of the day, but at certaintimes and places. Negative precepts aremore universal as to persons, because no man may be harmed. Second, because they are more obviouslyobserved by love of neighbor than are the affirmative. For a person who loves another, ratherrefrains from harming him than gives him benefits, which he is sometimes unableto give. (Commentary on the Letter ofSaint Paul to the Romans, Chapter 13, Lecture2)

Aquinas’sexamples hopefully make his meaning clear. Consider the negative precept “Do not commit adultery.” Because adultery is intrinsically evil, wemust never commit it, period, regardless of the circumstances. And because we therefore needn’t considercircumstances, no judgment of prudence is required in order to apply the precept to circumstances. Whatever the circumstances happen to be, wesimply refrain from committing adultery, and that’s that.

By contrast,applying the affirmative precept “Honor your father and mother” does requireattention to circumstances. To be sure,the precept never fails to be binding on us (which is what Aquinas means bysaying that it “obliges always”) but exactlywhat obeying it amounts to depends crucially on circumstances (which is whyhe says that “times and places” are relevant). For example, suppose your father commands you to bring him a bottle ofwine. Does honoring him oblige you to doso? It depends. Suppose he has had a hard day, finds itrelaxing to drink in moderation, and is infirm and has trouble walking. Then it would certainly dishonor your fatherto ignore him and make him get up and fetch the bottle himself. But suppose instead that he has a seriousdrinking problem, has already had too much wine, and will likely beat you oryour mother if he gets any drunker. Thenit would not dishonor him to refuseto bring the bottle.

As Aquinassuggests in the Romans commentary, affirmative precepts involve providingsomeone with a benefit of some kind, which one is “sometimes unable togive.” Consider the affirmative preceptto give alms. Even more obviously thanin the case of the precept to honor one’s parents, what following this preceptentails concretely is highly dependent on circumstances. Obviously one cannot always be giving alms,for even if one tried to do so, one would quickly run out of money and not onlybe unable to give any further alms, but would be in need of alms oneself. How to follow this affirmative preceptclearly requires making a judgment of prudence. How much money do I need for my own family? How much might I be able to spare for others,and how frequently? Exactly who, amongall the people who need alms, should I give to? Should I give by donating money, or instead by giving food and thelike? The answers to these questions arehighly dependent on circumstances and will vary from person to person, place toplace, and time to time.

The morecomplicated and variable the circumstances, the more difficult it can be todecide on a single correct answer and thus the greater the scope for reasonabledisagreement. The disagreement can bereasonable in either of two ways. First,what might be obligatory for one person given the details of his circumstancesmay not be obligatory for another person given the details of his own verydifferent circumstances. For example, arich man is bound to be obligated to give more in the way of alms than a poorman is. Second, disagreement can bereasonable insofar as the complexity of the situation might make it uncertainwhich course of action is best even for people in the same personal circumstances. Aquinas makes such points in the Summa Theologiae:

The practical reason… is busied with contingent matters,about which human actions are concerned: and consequently, although there isnecessity in the general principles, the more we descend to matters of detail,the more frequently we encounter defects. Accordingly then… in matters of action, truth or practical rectitude isnot the same for all, as to matters of detail, but only as to the generalprinciples: and where there is the same rectitude in matters of detail, it isnot equally known to all.

It is therefore evident that… as to the proper conclusions ofthe practical reason, neither is the truth or rectitude the same for all, nor,where it is the same, is it equally known by all. Thus it is right and true for all to actaccording to reason: and from this principle it follows as a proper conclusion,that goods entrusted to another should be restored to their owner. Now this is true for the majority of cases:but it may happen in a particular case that it would be injurious, andtherefore unreasonable, to restore goods held in trust; for instance, if theyare claimed for the purpose of fighting against one's country. And this principle will be found to fail themore, according as we descend further into detail, e.g. if one were to say thatgoods held in trust should be restored with such and such a guarantee, or insuch and such a way; because the greater the number of conditions added, thegreater the number of ways in which the principle may fail, so that it be notright to restore or not to restore. (Summa Theologiae I-II.94.4)

Points likethese are ignored when, for example, it is alleged that Catholics who favorenforcing immigration laws are somehow no less at odds with the Church’steaching than Catholics who favor legalized abortion. For one thing, as I’ve shown elsewhere,the Church herself acknowledges the legitimacy of restrictions onimmigration. For another, the principlesinvolved in the two cases are crucially different in exactly the ways Aquinasdescribes. “Do not murder” is a negativeprecept that flatly rules out a certain kind of action, regardless of thecircumstances. And since abortion is akind of murder, it flatly rules out abortion regardless of thecircumstances. There is no question ofprudential judgment here.

By contrast,“Welcome the stranger” is an affirmative precept, whose application is highlydependent on circumstances. Moreover,these circumstances involve millions of people, and complex matters of culture,law, economics, and national security. Here,even more than in the case of almsgiving, there is much room for reasonabledisagreement about how best to apply the precept. That would be obvious even if the Church hadnot explicitly acknowledged that immigration can be restricted for variousreasons (as, again, in fact she has).

It is thussheer sophistry to pretend that by appealing to the notion of prudentialjudgment, Catholics who support immigration restrictions are somehow trying torationalize dissent from Catholic teaching. On the contrary, they are (whether one agrees with them or not) fullywithin the bounds of what Catholic moral theology has always acknowledged to bea legitimate range of opinion among Catholics.

Similarsophistry is committed by those who speak as if supporting a living wage orgovernment provision of health care ought to be no less a matter of “pro-life”concern than abortion and euthanasia. Here too the comparison is specious. Abortion and euthanasia are flatly prohibited in all circumstancesbecause they violate the negative precept “Do not murder.” But principles like “Pay a living wage” or“Ensure health care for all” are affirmative precepts, and how best to apply themto concrete circumstances is highly dependent on various complex and contingenteconomic considerations. There can be noreasonable disagreement among Catholics about whether abortion and euthanasiashould be illegal. But there can bereasonable disagreement among them about whether a certain specific minimumwage law is a good idea, or which sort of economic arrangements provide thebest way to secure health coverage for all.

The samepoint can be made about other contemporary controversies, mutatis mutandis. And itapplies across the political spectrum (e.g. to those who, during the most recentpresidential election, pretended that there could be no reasonable doubt that anyloyal Catholic must vote for theirfavored candidate).

June 30, 2025

Talk it out

Time again foran open thread. Now’s your chance to get that off-topiccomment off your chest. The burning philosophicalor theological question you’ve been dying to raise? That political rant you’ve been meaning toinflict on fellow readers of this blog? Sometweet of mine that you wanted to complain about? All fair game. From real numbers to realpolitik,from That ‘70s Show to Kurtis Blow,from monads to gonads, there’s no limit to what you might talk about. (Other, that is, than the demands of goodtaste and basic sanity. So no trolling,please.) Previous open threads archived here.

Time again foran open thread. Now’s your chance to get that off-topiccomment off your chest. The burning philosophicalor theological question you’ve been dying to raise? That political rant you’ve been meaning toinflict on fellow readers of this blog? Sometweet of mine that you wanted to complain about? All fair game. From real numbers to realpolitik,from That ‘70s Show to Kurtis Blow,from monads to gonads, there’s no limit to what you might talk about. (Other, that is, than the demands of goodtaste and basic sanity. So no trolling,please.) Previous open threads archived here.

June 25, 2025

Solidarity

The ideal tostrive for in international relations is what in the natural law tradition andCatholic social teaching is called solidarity.On the one hand, this entails respecting the independence of nations and theirright to preserve their own identities, rather than absorbing them into aone-world blob; on the other hand, it entails promoting their cooperation andmutual assistance in what Pope Leo XIV calls the “family of peoples,” ratherthan a war of all against all in a Hobbesian state of nature.

The ideal tostrive for in international relations is what in the natural law tradition andCatholic social teaching is called solidarity.On the one hand, this entails respecting the independence of nations and theirright to preserve their own identities, rather than absorbing them into aone-world blob; on the other hand, it entails promoting their cooperation andmutual assistance in what Pope Leo XIV calls the “family of peoples,” ratherthan a war of all against all in a Hobbesian state of nature.Whereeconomics is concerned, this entails rejecting, on the one hand, a globalismthat dissolves national boundaries and pushes nations into a free tradedogmatism that is contrary to the interests of their citizens; but also, on theother hand, a mercantilism that walls nations off into mutually hostile campsand treats international economic relations as a zero-sum game. From the pointof view of solidarity, neither free trade nor protectionism should be made intoideologies; free trade policies and protectionist policies are merely toolswhose advisability can vary from case to case and require the judgment ofprudence.

Where warand diplomacy are concerned, this vision entails rejecting, on the one hand,the liberal and neoconservative project of pushing all nations to incorporatethemselves into the globalist blob by economic pressure, regime change, or thelike; but also, on the other hand, a Hobbesian realpolitik that sees all othernations fundamentally as rivals rather than friends, and seeks to bully theminto submission rather than cooperate to achieve what is in each nation’smutual interest.

Thissolidarity-oriented vision is an alternative to the false choice between whatmight be called the “neoliberal” and “neo-Hobbesian” worldviews competing today– each of which pretends that the other is the only alternative to itself. Itis the vision developed by thinkers in the Thomistic natural law tradition suchas Luigi Taparelli in the nineteenth century and Johannes Messner in thetwentieth, and which has informed modern Catholic social teaching.

Theprinciple of solidarity is fairly well-known to be central to natural law andCatholic teaching about the internalaffairs of nations (and famously gave a name to Polish trade union resistanceto Communist oppression). But it ought to be better known as the ideal topursue in relations between nationsas well.

(From a post today atX/Twitter)

June 23, 2025

Preventive war and the U.S. attack on Iran

Last week Iargued that the U.S. should stay out of Israel’s war with Iran. America has now entered the war by bombingthree facilities associated with Iran’s nuclear program. Is this action morally justifiable in lightof traditional just war doctrine?

Last week Iargued that the U.S. should stay out of Israel’s war with Iran. America has now entered the war by bombingthree facilities associated with Iran’s nuclear program. Is this action morally justifiable in lightof traditional just war doctrine? War aims?

Let us note,first, that much depends on exactly what the U.S. intends to accomplish. A week ago, before the attack, PresidentTrump warned thatTehran should be evacuated, called forIran’s unconditional surrender, and stated thatthe U.S. would not kill Iran’s Supreme Leader “for now” – thereby insinuatingthat it may yet do so at some future time. Meanwhile, many prominent voices in the president’s party have beencalling for regime change in Iran, and Trump himself this week has joined this chorus. Ifwe take all of this at face value, it gives the impression that the U.S. intendsor is at least open to an ambitious and open-ended military commitmentcomparable to the American intervention in Iraq under President Bush.

As I arguedin my previous essay, if this is whatis intended, U.S. action would not be morally justifiable by traditional justwar criteria. I focused on two points inparticular. First, the danger such interventionwould pose to civilian lives and infrastructure would violate the just warcondition that a war must be fought usingonly morally acceptable means. Second, given the chaos regime change would likely entail, and thequagmire into which the U.S. would be drawn, such an ambitious interventionwould violate the just war condition that amilitary action must not result in evils that are worse than the one beingredressed.

However, itis likely that we should not take thepresident’s words at face value. He hasa long-established tendency to engage in “trash talk” and to make off-the-cuffremarks that reflect merely what has popped into his head at the moment ratherthan any well thought out or settled policy decision. Furthermore, even when he does have in mindsome settled general policy goal, he appears prone to “making it up as he goes”where the details are concerned (as evidenced, for example, by his erraticmoves during the tariffcontroversy earlier this year). My bestguess is that he does not want an Iraq-style intervention but also does nothave a clear idea of exactly how far he is willing to go if Iran continues toresist his will.

As I said inmy previous essay, this is itself a serious problem. An erratic and woolly-minded leader who doesnot intend a wider war is liable nevertheless to be drawn into one by events, and can also cause otherharm, short of that, through reckless statements.

But so far,at least, the U.S. has in fact only bombed the facilities in question. Suppose for the sake of argument that this limited“one and done” intervention is all that is intended. Would this much be justifiable under just wardoctrine?

Preemptive versus preventive war

This bringsus to an issue which I only touched on in my earlier essay but which is obviouslyno less important (indeed, even more important) than the two criteria I focusedon: the justice of the cause forwhich the war is being fought, which is the first criterion of just wardoctrine. The reason I did not say moreabout it is that the issue is more complex than meets the eye. I think Israel can make a strong case that itsattack on Iran’s nuclear program meets the just cause condition for a just war. But it is harder for the U.S. to meet thatcondition, even on a “one and done” scenario.

Tounderstand why, we need to say something about a controversy that arose duringthe Iraq war and is highly relevant to the current situation, but hasn’treceived the attention it ought to. Irefer to the debate over the morality of preventivewar, which ethicists often distinguish from preemptive war.

In bothpreemptive war and preventive war, a country takes military action againstanother country that has not attacked it. And in both cases, the country initiating hostilities neverthelessclaims to be acting in self-defense. Thismight seem like sophistry and a manifest violation of the just cause criterionof just war doctrine. How can a countrythat begins a war claim self-defense?

But there isa crucial difference between the two cases. In a preemptive war, country B is preparingto attack country A but has not in fact yet done so. Country A simply preempts this coming attack by striking first, and can claimself-defense insofar as country B wasindeed going to attack it. Bycontrast, in a preventive war, country B was not preparing to attack country A. But country A attacks country B anyway, claiming that country B likely would pose a threat to A at some pointin the future.

Now, it isgenerally acknowledged among ethicists that preemptivewar can sometimes be morally justifiable. But preventive war is muchmore problematic and controversial. Thereare two main traditions of thinking on this subject (a useful overview of whichcan be found in chapter 9 of Gregory Reichberg’s book Thomas Aquinas on War and Peace). On the one hand, there is the natural lawtradition of thinking about just war criteria, associated with ScholasticCatholic writers like Thomas Aquinas and Francisco de Vitoria, Protestants likeHugo Grotius, and more recent Thomists like the nineteenth-century Catholic theologianLuigi Taparelli. According to thistradition, preventive war is flatly morally illegitimate. It violates the principle that a person orcountry cannot be harmed merely for some wrong it might do, but only for some wrong that it has in fact done.

The other mainapproach is the “realist” tradition associated with Protestant thinkers likeAlberico Gentili, Francis Bacon, and (with qualifications, since he also drewon the natural law tradition) Emer de Vattel. As Reichberg notes, whereas the natural law approach takes theinternational order to be governed by the moral law just as relations betweenindividuals are, the tendency of the realist tradition is to look at the internationalarena in something more like Hobbesian terms. And the realist tradition is thus more favorable to preventive war as atool nations might deploy as they negotiate this Hobbesian state ofnature.

As Reichbergalso notes, Vattel put the following conditions on the justifiability of some countryA’s initiating a preventive war against another country B. First, country B must actually pose a potential threat to country A. Second, country B must threaten the very existence of country A. Third, it must intend to pose such a threat. And fourth, it must somehow have actually shown signs of evildoing inthe past. Vattel adds the condition thatcountry A must first have tried and failed to secure guarantees from country Bthat it will not attack A.

Much of thecontroversy over the Iraq war had to do with whether a preventive war ismorally justifiable, and the Bush administration did sometimes say things thatimplied that the war was preventive in nature. But as I argued at the time, this particular aspect of the debate was ared herring. The main rationale for thewar was that Saddam had not complied with the terms of the ceasefire of theGulf War, so that the U.S. and her allies were justified in re-startinghostilities in order to force compliance. Whatever one thinks of this as a rationale, it is not an appeal topreventive war. Hence any criticism ofthe Iraq war should, in my view, focus on other aspects of it (such as theintelligence failure vis-à-vis WMD and the folly of the nation-buildingenterprise the war led to).

The case of Iran

What mattersfor present purposes, though, is the relevance of all this to the war withIran. Now, it was Israel rather thanIran that initiated the current hostilities. Was this morally justifiable?

It seemsclear to me that it was justifiable by Vattel’s criteria for preventivewar. But as a natural law theorist, I don’tthink preventive war can be justified, so that that particular point ismoot. However, that does not entail thatit was wrong for Israel to attack Iran’s nuclear program. For it can plausibly be seen as a justifiablepreemptive rather than preventive attack. To be sure, Iran was not preparing a specificnuclear attack operation, since it does not actually have nuclear weapons. But Israel can make the following argument: Iranhas already been in a state of war with Israel for years; its leadership hasrepeatedly threatened Israel’s destruction; if it acquired nuclear weapons, itwould actually be capable of carrying out this threat; and it has for yearsbeen trying to acquire them. Destroyingits nuclear program is therefore not merely a preventive action, but in the relevant sense an act of preempting an attack (in its very earlieststages, as it were) that Israel has good reason to think Iran actually intends.

This seemsto me a strong argument, so that I think that Israel can indeed make the casethat it has a just cause, at least insofar as its aim is simply to destroy Iran’snuclear program. (A more ambitious goalof regime change would be much harder to justify, for the same reason that, asI said in my earlier article, it would not be justifiable for the U.S. toattempt regime change. But here I amjust addressing the more limited aim of destroying Iran’s nuclear capability.)

However,this does not entail that the U.S. isjustified in attacking Iran. Note firstthat the recent U.S. bombing was not carried out in response to any act of waron Iran’s part against the United States. True, some have pointed out that U.S. and Iranian-backed forces havebeen involved in various skirmishes in recent decades. But it would be dishonest to pretend that thathad anything to do with the recent U.S. action. If Iran’s nuclear program had not been in the picture, Trump would nothave ordered the bombing. Hence, if theU.S. is claiming to be acting in justifiable self-defense, it could plausiblydo so only by the criteria governing preemptive war or preventive war.

But in fact,it cannot plausibly do so. Note first that the U.S. action does not meeteven Vattel’s criteria for preventive war. For even if Iran already had nuclear weapons, it would not pose a threatto the very existence of the United States (the way it would pose a threat to the very existence of Israel). For one thing, Iran lacks any plausible meansof getting a nuclear device into the United States; for another, even if itcould do so, it would hardly be able to destroy the country as a whole. Hence, any “preventive war” case for U.S. self-defense is fanciful. And if that is true, then it is even moreobvious that the U.S. cannot plausibly meet the more stringent criteria for a preemptive war case. Iran simply cannot plausibly be said to havebeen in the process of planning a nuclear attack on the U.S., even in thelooser sense in which it might be said to have been planning such an attack onIsrael.

I concludethat no serious case can be made that the U.S. attack on Iran was a justifiableact of self-defense. However, there isone further way the attack might seem to be justified. Couldn’t the U.S. argue that, even though itcouldn’t plausibly hold that it was defending itself, it was justifiably helping its ally Israel to defend itself?

Certainly itcan be justifiable to help an ally to defend itself. But whether it ought to do so in anyparticular case depends on various circumstances. For example, suppose Iran actually had a nuclearweapon and it was known that it was about to deploy it against Israel and thatonly the U.S. could stop the attack. Iwould say that in that sort of scenario, the U.S. not only could intervene to stop such an attack but would be morally obligated to do so. And it would also be morally justifiable forthe U.S. to intervene in order to help Israel in other, less dire scenarios.

But we arenot now in a situation remotely close to such scenarios. Thereare various ways Israel could stop Iran’s nuclear program by itself – as,it appears, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has acknowledged. Meanwhile, there are serious potentialdownsides to U.S. involvement. Americantroops could be killed by Iranian retaliatory strikes, the U.S. economy couldbe hit hard if Iran closes off the Strait of Hormuz, and if the Iranian regimewere to collapse the U.S. could be drawn into a quagmire in attempting tomitigate the resulting chaos. Yes, suchthings might not in fact happen, butthey plausibly could happen, andkeeping one’s fingers crossed is not a serious way to approach the applicationof just war criteria. If Israel doesn’tstrictly need the U.S. to interveneand intervention poses such potential risks to U.S. interests, then the U.S.should not intervene.

Hence I aminclined to conclude the following about the U.S. attack, even if (as we canhope) it does indeed turn out to be a “one and done” operation. Was American bombing of Iranian nuclearfacilities intrinsically wrong? No. But did it meet all theconditions of just war doctrine, all things considered? No.

June 21, 2025

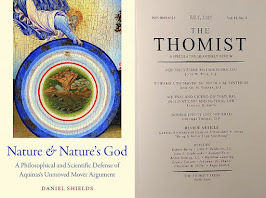

Shields on Aquinas on the Unmoved Mover

My review ofDaniel Shields’ important recent book

Nature and Nature’s God: A Philosophical andScientific Defense of Aquinas’s Unmoved Mover Argument

appears in theJuly 2025 issue of

The Thomist

.

My review ofDaniel Shields’ important recent book

Nature and Nature’s God: A Philosophical andScientific Defense of Aquinas’s Unmoved Mover Argument

appears in theJuly 2025 issue of

The Thomist

.

June 17, 2025

The U.S. should stay out of Israel’s war with Iran (Updated)

Let me sayat the outset that I agree with the view that it would be bad for the Iranianregime to acquire a nuclear weapon. Howclose it is to actually acquiring one, I do not know. I do know that the claim that such acquisitionis imminent has been made for decades now,and yet it has still not happened. Inany event, it is Israel rather than the U.S. that would be threatened by suchacquisition, and Israel has proven quite capable of taking care of itself. There is no need for the U.S. to enter thewar, and it is in neither the U.S.’s interests nor the interests of the rest ofthe region for it to do so.

Let me sayat the outset that I agree with the view that it would be bad for the Iranianregime to acquire a nuclear weapon. Howclose it is to actually acquiring one, I do not know. I do know that the claim that such acquisitionis imminent has been made for decades now,and yet it has still not happened. Inany event, it is Israel rather than the U.S. that would be threatened by suchacquisition, and Israel has proven quite capable of taking care of itself. There is no need for the U.S. to enter thewar, and it is in neither the U.S.’s interests nor the interests of the rest ofthe region for it to do so.YetPresident Trump has this week indicated that the U.S. is joining theconflict. He has said that“we now have complete and total control of the skies over Iran,” and that “weknow exactly where the so-called ‘Supreme Leader’ is hiding… we are not goingto take him out (kill!), at least not for now.” The “we” implies that the U.S. has already entered the war on Israel’sside. He has said:

Iran should have signed the “deal” I told them to sign. Whata shame, and waste of human life. Simply stated, IRAN CAN NOT HAVE A NUCLEARWEAPON. I said it over and over again! Everyone should immediately evacuateTehran!

Taken atface value, this indicates that the U.S. will participate in an attack thatwill threaten the entire city of Tehran. And he hascalled for Iran’s “unconditional surrender.” Meanwhile, Israel is indicatingthat regime change is among the aims of its war with Iran.

There aretwo criteria of just war theory that the president is violating, at least if wetake his words at face value. First, fora war to be just, it must be fought using only morally legitimate means. Thisincludes a prohibition on intentionally targeting civilians and civilianinfrastructure. To be sure, just wartheory allows that there can be cases where harm to civilians and civilian infrastructurecan be permissible, but only if (a) this is the foreseen but unintendedbyproduct of an attack on military targets, and (b) the harm caused tocivilians and civilian infrastructure is not out of proportion to the good achievedby destroying those military targets.

It is thestandard view among just war theorists that attacks such as the atomic bombingsof Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the firebombing of Dresden, violated thiscriterion of just war theory and thus were gravely immoral. They are manifestly immoral if the intentionwas to kill and terrorize civilians. Butthey were also immoral even if the intention was to damage military targets,because the harm to civilians and civilian infrastructure was massively out ofproportion to the good achieved by attacking such military targets.

Now, forPresident Trump to warn that “everyone should immediately evacuate Tehran”indicates that the U.S. and Israel intend a bombing campaign that will causemassive destruction to the city as a whole. It is hard to see how that could be consistent with the just warcondition of using only morally legitimate means. This is true, by the way, even if (as isunlikely) the nearly ten million people of Tehran could in fact beevacuated. Civilian homes and otherproperty, and not just civilian lives, must, as far as reasonably possible, berespected in a just war.

The call for“unconditional surrender” is also highly problematic. As the Catholic philosopher ElizabethAnscombe said of Allied war demands during World War II in her famous essay “Mr.Truman’s Degree”:

It was the insistence on unconditional surrender that was theroot of all evil. The connection betweensuch a demand and the need to use the most ferocious methods of warfare will beobvious. And in itself the proposal ofan unlimited objective in war is stupid and barbarous.

When acountry tells an enemy’s government and citizens that it will settle fornothing less than their surrender with no conditions at all – thereby puttingthemselves entirely at their foes’ mercy – they are obviously bound to fightmore tenaciously and brutally, which will tempt the threatening country tosimilarly brutal methods of warfare in response.

The secondcriterion of just war theory most relevant to the present crisis is that inorder to be just, a military action mustnot result in evils that are worse than the one being redressed. Now, as the history of the aftermath of thewars in Iraq and Afghanistan shows, regime change in the Middle East is likelyto have catastrophic consequences for all concerned. Both of those conflicts resulted in years ofcivil war, tens or even hundreds of thousands of casualties, and, in the caseof Afghanistan, a successor regime hostile to the U.S. As Sohrab Ahmari arguesthis week at UnHerd, similarchaos is bound to follow a collapse of the Iranian regime. Regime change thus seems too radical a waraim. More limited measures, like those thathave for decades now kept Iran’s nuclear weapons program from succeeding, arethe most that can be justified.

As they routinelydo, Trump’s defenders may suggest that his words should not be taken at facevalue, but interpreted as mere “trash talk” or perhaps as exercises in “thinkingout loud” rather than as final policy decisions. But this helps their case not at all. War is, needless to say, an enterprise ofenormous gravity, calling for maximum prudence and moral seriousness. Even speaking about the possibility must bedone with great caution. (Think of thechaos that could follow upon trying quickly to evacuate a city of nearly tenmillion people, even if there were no actual plan to bomb it.) A president who is instead prone to woolly thinkingand flippant speech about matters of war is a president whose judgment aboutthem cannot be trusted. (And asI have argued elsewhere, he has already in other ways proven himself tohave unsound judgment about such things.)

It alsoshould not be forgotten that for Trump to bring the U.S. into a major new warin the Middle East would be contrary to his own longstanding rhetoric. For example, in 2019 he said:

The United States has spent EIGHT TRILLION DOLLARS fightingand policing in the Middle East. Thousands of our Great Soldiers have died orbeen badly wounded. Millions of people have died on the other side. GOING INTOTHE MIDDLE EAST IS THE WORST DECISION EVER MADE.....

But then, contradictoryand reckless statements are par for the course with Trump. For example, Trump has portrayed himself aspro-life, but then cameout in support of keeping abortion pills available and of federal fundingfor IVF. He promised to bring pricesdown, but haspursued trade policies that are likely to make prices higher. His DOGE project was predicated on the needto bring federal spending under control, but now he supports a bill that willadd another $3 trillion to the national debt. And so on. His record is one thatcan be characterized as unstable and unprincipled at best and shamelessly dishonestat worst. This reinforces the conclusionthat his judgment on grave matters such as war cannot be trusted.

I concludethat Trump’s apparent plan to bring the U.S. into Israel’s war with Iran is notjustifiable and that he ought to be resisted on this matter (as he ought to beon other matters, such as abortion and IVF).

UPDATE 6/19:UnHerd’s Freddie Sayers interviewsJohn Mearsheimer and Yoram Hazony on the Israel-Iran war. It’s a superb discussion – sober,intelligent, nuanced and well-informed, precisely the opposite of mostdiscourse about these issues. Thoughcoming from very different perspectives, Mearsheimer and Hazony agree that itis better for the U.S. to stay out of the conflict.

While somehave claimed that only the U.S. can take out the Iranian facility at Fordow,Hazony disagrees. Moreover, itis uncertain that America’s “bunker buster” bomb really would destroy Fordow. And even if it did, Fordow could be quickly rebuilt,one expert opining that an attack “might set the program back [only] six monthsto a year.”

Today, WhiteHouse press secretary Karoline Leavitt claimedthat Iran can now within just a couple of weeks produce a nuclear weapon thatwould “pose an existential threat not just to Israel but to the United Statesand to the entire world.” Yet she alsoannounced that President Trump would be taking a couple of weeks to decide whatto do. Needless to say, her firststatement is very hard to take seriously in light of her second statement. Moreover, Trump’s own Director of NationalIntelligence Tulsi Gabbard hadrecently stated that “Iran is not building a nuclear weapon and SupremeLeader Khamenei has not authorized the nuclear weapons program he suspended in2003.”

In short,both the case for U.S. intervention, and the administration’s credibility onthe issue, appear to be falling apart.

The U.S. should stay out of Israel’s war with Iran

Let me sayat the outset that I agree with the view that it would be bad for the Iranianregime to acquire a nuclear weapon. Howclose it is to actually acquiring one, I do not know. I do know that the claim that such acquisitionis imminent has been made for decades now,and yet it has still not happened. Inany event, it is Israel rather than the U.S. that would be threatened by suchacquisition, and Israel has proven quite capable of taking care of itself. There is no need for the U.S. to enter thewar, and it is in neither the U.S.’s interests nor the interests of the rest ofthe region for it to do so.

Let me sayat the outset that I agree with the view that it would be bad for the Iranianregime to acquire a nuclear weapon. Howclose it is to actually acquiring one, I do not know. I do know that the claim that such acquisitionis imminent has been made for decades now,and yet it has still not happened. Inany event, it is Israel rather than the U.S. that would be threatened by suchacquisition, and Israel has proven quite capable of taking care of itself. There is no need for the U.S. to enter thewar, and it is in neither the U.S.’s interests nor the interests of the rest ofthe region for it to do so.YetPresident Trump has this week indicated that the U.S. is joining theconflict. He has said that“we now have complete and total control of the skies over Iran,” and that “weknow exactly where the so-called ‘Supreme Leader’ is hiding… we are not goingto take him out (kill!), at least not for now.” The “we” implies that the U.S. has already entered the war on Israel’sside. He has said:

Iran should have signed the “deal” I told them to sign. Whata shame, and waste of human life. Simply stated, IRAN CAN NOT HAVE A NUCLEARWEAPON. I said it over and over again! Everyone should immediately evacuateTehran!

Taken atface value, this indicates that the U.S. will participate in an attack thatwill threaten the entire city of Tehran. And he hascalled for Iran’s “unconditional surrender.” Meanwhile, Israel is indicatingthat regime change is among the aims of its war with Iran.

There aretwo criteria of just war theory that the president is violating, at least if wetake his words at face value. First, fora war to be just, it must be fought using only morally legitimate means. Thisincludes a prohibition on intentionally targeting civilians and civilianinfrastructure. To be sure, just wartheory allows that there can be cases where harm to civilians and civilian infrastructurecan be permissible, but only if (a) this is the foreseen but unintendedbyproduct of an attack on military targets, and (b) the harm caused tocivilians and civilian infrastructure is not out of proportion to the good achievedby destroying those military targets.

It is thestandard view among just war theorists that attacks such as the atomic bombingsof Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the firebombing of Dresden, violated thiscriterion of just war theory and thus were gravely immoral. They are manifestly immoral if the intentionwas to kill and terrorize civilians. Butthey were also immoral even if the intention was to damage military targets,because the harm to civilians and civilian infrastructure was massively out ofproportion to the good achieved by attacking such military targets.

Now, forPresident Trump to warn that “everyone should immediately evacuate Tehran”indicates that the U.S. and Israel intend a bombing campaign that will causemassive destruction to the city as a whole. It is hard to see how that could be consistent with the just warcondition of using only morally legitimate means. This is true, by the way, even if (as isunlikely) the nearly ten million people of Tehran could in fact beevacuated. Civilian homes and otherproperty, and not just civilian lives, must, as far as reasonably possible, berespected in a just war.

The call for“unconditional surrender” is also highly problematic. As the Catholic philosopher ElizabethAnscombe said of Allied war demands during World War II in her famous essay “Mr.Truman’s Degree”:

It was the insistence on unconditional surrender that was theroot of all evil. The connection betweensuch a demand and the need to use the most ferocious methods of warfare will beobvious. And in itself the proposal ofan unlimited objective in war is stupid and barbarous.

When acountry tells an enemy’s government and citizens that it will settle fornothing less than their surrender with no conditions at all – thereby puttingthemselves entirely at their foes’ mercy – they are obviously bound to fightmore tenaciously and brutally, which will tempt the threatening country tosimilarly brutal methods of warfare in response.

The secondcriterion of just war theory most relevant to the present crisis is that inorder to be just, a military action mustnot result in evils that are worse than the one being redressed. Now, as the history of the aftermath of thewars in Iraq and Afghanistan shows, regime change in the Middle East is likelyto have catastrophic consequences for all concerned. Both of those conflicts resulted in years ofcivil war, tens or even hundreds of thousands of casualties, and, in the caseof Afghanistan, a successor regime hostile to the U.S. As Sohrab Ahmari arguesthis week at UnHerd, similarchaos is bound to follow a collapse of the Iranian regime. Regime change thus seems too radical a waraim. More limited measures, like those thathave for decades now kept Iran’s nuclear weapons program from succeeding, arethe most that can be justified.

As they routinelydo, Trump’s defenders may suggest that his words should not be taken at facevalue, but interpreted as mere “trash talk” or perhaps as exercises in “thinkingout loud” rather than as final policy decisions. But this helps their case not at all. War is, needless to say, an enterprise ofenormous gravity, calling for maximum prudence and moral seriousness. Even speaking about the possibility must bedone with great caution. (Think of thechaos that could follow upon trying quickly to evacuate a city of nearly tenmillion people, even if there were no actual plan to bomb it.) A president who is instead prone to woolly thinkingand flippant speech about matters of war is a president whose judgment aboutthem cannot be trusted. (And asI have argued elsewhere, he has already in other ways proven himself tohave unsound judgment about such things.)

It alsoshould not be forgotten that for Trump to bring the U.S. into a major new warin the Middle East would be contrary to his own longstanding rhetoric. For example, in 2019 he said:

The United States has spent EIGHT TRILLION DOLLARS fightingand policing in the Middle East. Thousands of our Great Soldiers have died orbeen badly wounded. Millions of people have died on the other side. GOING INTOTHE MIDDLE EAST IS THE WORST DECISION EVER MADE.....

But then, contradictoryand reckless statements are par for the course with Trump. For example, Trump has portrayed himself aspro-life, but then cameout in support of keeping abortion pills available and of federal fundingfor IVF. He promised to bring pricesdown, but haspursued trade policies that are likely to make prices higher. His DOGE project was predicated on the needto bring federal spending under control, but now he supports a bill that willadd another $3 trillion to the national debt. And so on. His record is one thatcan be characterized as unstable and unprincipled at best and shamelessly dishonestat worst. This reinforces the conclusionthat his judgment on grave matters such as war cannot be trusted.

I concludethat Trump’s apparent plan to bring the U.S. into Israel’s war with Iran is notjustifiable and that he ought to be resisted on this matter (as he ought to beon other matters, such as abortion and IVF).

Edward Feser's Blog

- Edward Feser's profile

- 334 followers