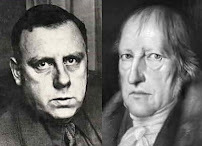

MacIntyre on Hegel on human action

Phrenologywas the pseudoscience that aimed to link psychological traits to the morphologyof the skull. Physiognomy was thepseudoscience that aimed to link such traits to facial features. In his Phenomenologyof Spirit, Hegel critiques these pseudosciences. Since they are now widely acknowledged to bepseudosciences, it might seem that Hegel’s critique can be of historicalinterest only. But as the late AlasdairMacIntyre pointed out in his essay “Hegel: On Faces and Skulls,” Hegel’s mainpoints can be applied to a critique of today’s fashionable attempts to predictpsychological traits and human actions from physiological and genetictraits. (The essay appears in thecollection Philosophy Through Its Past,edited by Ted Honderich.)

Phrenologywas the pseudoscience that aimed to link psychological traits to the morphologyof the skull. Physiognomy was thepseudoscience that aimed to link such traits to facial features. In his Phenomenologyof Spirit, Hegel critiques these pseudosciences. Since they are now widely acknowledged to bepseudosciences, it might seem that Hegel’s critique can be of historicalinterest only. But as the late AlasdairMacIntyre pointed out in his essay “Hegel: On Faces and Skulls,” Hegel’s mainpoints can be applied to a critique of today’s fashionable attempts to predictpsychological traits and human actions from physiological and genetictraits. (The essay appears in thecollection Philosophy Through Its Past,edited by Ted Honderich.)That ideaalone makes Hegel’s arguments worthy of our consideration. For it would certainly be of interest if itturned out that the fundamental problems with pseudosciences like phrenologyand physiognomy had to do, not with their inadequacies vis-à-vis the empiricalevidence, but with deeper philosophical assumptions they share with purportedlymore empirically plausible and respectable versions of materialistreductionism. The arguments are not,however, presented with maximal crispness. But they are suggestive and worth trying to tease out. What follows is an attempt to do so (and itsfocus is on Hegel as MacIntyre reads him rather than on Hegel’s own texts).

The appeal to the past

MacIntyrenotes several ways in which Hegel takes there to be a mismatch between brute anatomicaland physiological facts on the one hand, and human thought and action on theother. But it seems to me that there aretwo main lines of argument identified by MacIntyre. The first, as I understand it, goes likethis. Scientific explanations, includingphysiological explanations, appeal to general propositions, such aspropositions of the form “For every x, if x is F then x is G.” For example, we might explain why aparticular glass of water froze by saying “For every x, if x is water then xwill freeze at 32 degrees Fahrenheit.” Our predicates F and G refer to universals, and we explain theparticular phenomenon by simply noting that it is an instance of a completelygeneral truth.

However,Hegel argues, human actions cannot be understood in this way. Suppose, for example (mine, not Hegel’s orMacIntyre’s), that you have a fight with your brother over some longstandinggrudge between the two of you. Properlyto explain this event requires reference to particular earlier events in yourhistory, such as a promise to you that he once broke, or an occasion when youpublicly insulted and embarrassed him. And those events will in turn be explicable in terms of yet other andearlier particular events. Understandingthe character of these events will also involve attention to a variety of contextualdetails, such as who exactly was present on the occasion you publicly insultedhim, and exactly what it was he had promised to do and why it was significant. Furthermore, it will involve attention to howall the relevant parties conceived ofthese various details.

Thesecircumstances, thinks Hegel (as presented by MacIntyre) simply cannot becaptured in general propositions of the kind to which scientific explanationsappeal. In particular, there are no truegeneralizations to the effect of “For every x and every y, if x and y arebrothers and x breaks a promise to y, then x and y will get in a fight severalyears later” (or whatever). What makesthe sequence of events intelligible, in Hegel’s view, is not that it is aparticular instance of a general pattern, where all events of the one kind willbe followed by events of the other. Rather, that you acted in light of certain particular, contingent historical circumstances is an ineliminableaspect of the story, and cannot be captured in general or lawlikepropositions. You are responding to those circumstances qua particular, notto just any old circumstances that happened to be of that general type. As MacIntyre writes, “to respond to aparticular situation, event, or state of affairs is not to respond to any situation,event, or state of affairs with the same or similar properties in some respect;it is to respond to that situation conceivedby both the agents who respond to it and those whose actions constitute it asparticular” (p. 329).

What shouldwe think of this argument? I’m notsure. Certainly it would need muchtightening up before it could be judged compelling. However, it does seem to be at least in thegeneral ballpark of arguments that I think are powerful. For example, it is reminiscent of DonaldDavidson’s famous principleof the anomalism of the mental, according to which there can be nostrict laws by which mental events might be predicted and explained. (Though Davidson’s argument too needstightening up.)

The appeal to the future

What seemsto me to be a second, distinct Hegelian argument discussed by MacIntyre (albeitnot characterized by him as such) is expressed in this passage:

From the fact that an agent has a given trait, we cannot deduce what he will do in any givensituation, and the trait cannot itself be specified in terms of somedeterminate set of actions that it will produce… [T]he crucial fact aboutself-consciousness… is, its self-negating quality: being aware of what I am isconceptually inseparable from confronting what I am not but could become. Hence, for a self-conscious agent to have atrait is for that agent to be confronted by an indefinitely large set ofpossibilities of developing, modifying, or abolishing that trait. Action springs not from fixed and determinatedispositions, but from the confrontation in consciousness of what I am by whatI am not. (p. 331)

The ideahere seems to be that to be conscious of oneself as an agent is, of its nature,precisely to be conscious of the possibility of an indefinite number ofalternative choices. By contrast, tounderstand an anatomical or physiological feature is to know it as limited to acertain specific and relatively narrower range of effects in might have. Whereas, in Hegel’s first argument, the ideais that a reductionist physiological explanation cannot account for thesignificance of one’s past, in this argument the idea is that it cannot accountfor the openness of one’s future.

To make thepoint a little clearer, consider this passage from earlier in MacIntyre’sessay:

The relation of external appearance, including the facialappearance, to character is such that the discovery that any externalappearance is taken to be a sign of a certain type of character is a discoverythat the agent may then exploit to conceal his character. (p. 325)

The pointhere seems to be this. Suppose someonetold me that he could, from my facial expressions, read off my character andthus predict my future actions. Knowingthis, I could make sure that in the future I avoid the facial expressions Iwould otherwise normally be inclined toward, so that my interlocutor will bethrown off and his predictions will fail. Similarly, suppose someone told me that, based on what he had determinedfrom scanning my brain, he predicted that I would make a cup of coffee in thenext half hour. Even if I were inclinedto do so, I could now choose otherwise simply to prove him wrong. There’s an openness to alternative possibilitiesin the behavior of human beings that differentiates them from the rigidbehavior of merely physical systems, including those that comprise the micro-levelparts of human beings considered in isolation from the whole.

This line ofthought calls to mind the similar argumentdeveloped by Jean-Paul Sartre in Beingand Nothingness. He famously draws adistinction there between being-in-itselfand being-for-itself. Being-in-itself is the kind of reality had bya mere physical object as it exists objectively or independently of human consciousness. It is simply given or fixed. By contrast, being-for-itself, which is thehuman agent, is consciousness as it projects forward toward an unrealizedpossibility. Unlike being-in-itself, itis open to different possibilities rather than entirely fixed or determined. To deny free will is essentially to conflatebeing-for-itself with being-in-itself, but this cannot be done, because theyare simply irreducibly different. Naturally,Sartre’s argument, and Hegel’s too, would require tightening up if we are to makethem compelling.

Now, thegeneral idea that the conceptual and logical structure of thought are simplyirreducibly different from, and inexplicable in terms of, any collection ofphysical facts and their causal relations, is something I defend rigorously andat length in chapters 8 and 9 of my book ImmortalSouls. I take it that Hegel’sfirst argument is aiming at something like that conclusion. And the general idea that human action isirreducibly teleological, and in particular that it cannot be analyzed in termsof efficient-causal relations (of the kind that obtain between physiologicalphenomena, for example) is something I defend in depth in chapter 4 of thebook. I take it that Hegel’s secondargument is aiming at something like that conclusion.

Hence I am,in a very general way, sympathetic at least to the basic idea of the kind ofposition MacIntyre attributes to Hegel. I leave as a homework exercise the question whether there are, in thatposition, ingredients for a line of argument that is both compelling and independentof considerations of the kind I set out in the book.

Edward Feser's Blog

- Edward Feser's profile

- 326 followers