Edward Feser's Blog, page 52

October 27, 2018

Violence in word and action

Bernard Wuellner’s always-useful

Dictionary of Scholastic Philosophy

defines violence as “action contrary to the nature of a thing.” Readers of Aristotle and Aquinas will be familiar with this usage, which is reflected in their distinction between natural and violent motion. Some of their applications of this distinction presuppose obsolete science. For example, we now know that physical objects do not have motion toward the center of the earth, specifically, as their natural end. Hence projectile motion away from the earth is not, after all, violent. But the distinction itself is not obsolete. For example, trapping or killing an animal is obviously violent in the relevant sense. It is acting contrary to the natural ends of the animal. Violence is not per se bad. When a lion kills a gazelle, it acts violently insofar as it frustrates the natural ends of the gazelle. But it thereby fulfills rather than frustrates its own natural ends. It is good for the lion to do this, even if it is bad for the gazelle. Indeed, to prevent the lion from acting violently toward other things would itself be an act of violence toward the lion, insofar as it would be preventing the lion from doing what its nature prompts it to do. This violence toward the lion can itself be a good thing – for example, if you’ve got a pet gazelle you want to protect.

Bernard Wuellner’s always-useful

Dictionary of Scholastic Philosophy

defines violence as “action contrary to the nature of a thing.” Readers of Aristotle and Aquinas will be familiar with this usage, which is reflected in their distinction between natural and violent motion. Some of their applications of this distinction presuppose obsolete science. For example, we now know that physical objects do not have motion toward the center of the earth, specifically, as their natural end. Hence projectile motion away from the earth is not, after all, violent. But the distinction itself is not obsolete. For example, trapping or killing an animal is obviously violent in the relevant sense. It is acting contrary to the natural ends of the animal. Violence is not per se bad. When a lion kills a gazelle, it acts violently insofar as it frustrates the natural ends of the gazelle. But it thereby fulfills rather than frustrates its own natural ends. It is good for the lion to do this, even if it is bad for the gazelle. Indeed, to prevent the lion from acting violently toward other things would itself be an act of violence toward the lion, insofar as it would be preventing the lion from doing what its nature prompts it to do. This violence toward the lion can itself be a good thing – for example, if you’ve got a pet gazelle you want to protect.Notice that there is nothing special about animals here, even if the violence they inflict and suffer is especially vivid. Even herbivores act violently when they eat plants. After all, to eat a plant is to frustrate its natural ends.

You might ask: “But doesn’t natural law theory say that it’s always bad to act contrary to nature?” No, that’s not what it says. It says that it’s bad for human beings to act contrary to their ownnature. But like a lion, a human being can do something good by acting contrary to another thing’s nature, as we do any time we kill a plant or animal in order to eat it and thereby nourish ourselves. What is good for a thing is determined by its own nature, not “nature” in some larger abstract sense.

Having said that, since human beings are social animals, what is natural for other human beings is part of what is constitutive of any one human being’s good. For example, parents realize their own natural ends precisely by helping their children to realize theirs. The human race is a kind of extended family, and part of what is good for us is to act in a way consistent with everyone else’s realizing what is good for them (though our positive obligations to help others flourish are in general less strong the farther removed they are from us, as I have explained elsewhere). Hence it is contrary to natural law for us to act toward other human beings the way we might be permitted to act toward plants and non-human animals.

Now, chief among our natural ends are those that follow from our being rational animals, possessing intellect and free will. Hence, killing or otherwise physically harming other human beings is not the only way of acting violently toward them, in the sense of acting contrary to their nature. There is also a kind of violence involved when we act contrary to their rational nature, by refusing to engage them at the level of rational discourse or frustrating their lawful free choices.

Hence, as rational, social animals, it is constitutive of what is good for each of us to engage with other human beings in a way that respects their intellects and free wills. When dealing with other human beings, there is a moral presumption that when we want them to think or to do something, we have to secure this outcome by persuading them rationally rather than resorting to force, threats or other kinds of intimidation, psychological manipulation, or the like.

This presumption can be overridden. For example, children often do not want to do what their parents tell them to do, even when what the parents are asking of them is perfectly reasonable and good for them. Such children are acting contrary to reason, and parents have the authority to coerce them or punish them for disobedience by reasonable methods (verbal rebukes, spankings, taking away privileges, or whatever).

An insane person may also be coerced, precisely because he is incapable of rational action and may be a danger to himself or others. Those guilty of crimes have also thereby forfeited their rights to certain goods, which might include their property, their liberty, or in some cases even their lives, and they may be coerced accordingly. Indeed, as Aquinas argues, our inclination to punish evildoers is itself a natural and good human inclination, necessary for our well-being as rational social animals. (See chapter 1 of By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed for a detailed explanation and defense of the natural law account of punishment.)

So, punishing wrongdoers is not a morally objectionable form of violence – and indeed, in one sense it is arguably not really a form of violence at all, since their nature as rational social animals entails that they can be punished for wrongdoing, so that to punish them is not to act contrary to their nature. In fact, to prevent lawful authorities from ever inflicting just punishments would itself be a kind of “violence” in the sense we are considering, because it would be contrary to what the natural law requires them to do.

One of the implications of all this is that blanket condemnations of violence are muddleheaded and, indeed, immoral. Some violence is bad, but not all of it is, and sometimes it can even be morally required.

(Gandhi is reputed to have defended an ethic of nonviolence by saying that taking an eye for an eye would make the whole world blind. It seems he may never actually have said it, which is a good thing for him, because it is a pretty stupid thing to say. The lex talionis principle does not hold that you should inflict on just anyonea harm proportional to the one he has inflicted. It holds that you should inflict on wrongdoers, specifically, harms proportional to the ones they have inflicted on the innocent. But lawful authorities who inflict harms on the guilty are not wrongdoers, so a consistent application of the lex talionis principle does not entail that they too should be harmed. Hence, if the pseudo-Gandhian quote were rephrased in such a way that it was not aimed at a caricature, it would instead say something like “Taking an eye for an eye would make blind everyone who has unjustly taken both of some other person’s eyes.” Or, since most defenders of lex talionis don’t think that literally gouging out eyes is a good idea all things considered, a better paraphrase would be “Inflicting proportional harms on wrongdoers would leave all wrongdoers proportionally harmed.” But then the obvious response to this corrected pseudo-Gandhian one-liner is: “Yes, it would. That’s the point.”)

What has been said also casts light on why torture is morally objectionable. The problem with torture is not that it involves inflicting pain or something otherwise unpleasant. A child can deserve a spanking or the loss of some privilege, and a criminal can deserve much worse, and inflicting such punishments is not wrong. The problem with torture is also not that it involves coercing the will. When a parent threatens a child with punishment, or a policemen threatens to shoot a bank robber if he does not lay down his weapon, or a victim punches an attacker in order to get him to stop the attack, the will is coerced, but entirely justly.

The problem with torture is that it involves completely subverting the intellect and will altogether, essentially attempting to reduce the rational animal to a non-rational animal. In that way, it is contrary to the victim’s nature in a way that merely inflicting pain or coercing him is not. (I would tentatively suggest that it amounts to the perversion of a faculty. For it is essentially a matter of trying to get someone’s intellect and will to a certain result by means of a method that subverts the proper functioning of the intellect and will.)

Yet another implication of the analysis of violence given above is that to respond to an opponent who attempts to engage with you in a rational way with vituperation, ad hominem attacks, intimidation, and the like is also a morally objectionable kind of violence. For it involves acting contrary to the person’s rational nature.

Notice that I am not saying that polemical engagement with just any opponent is necessarily wrong. As I have argued several times over the years (e.g. here, here, and here), it can be legitimate to respond to an opponent with polemical harshness – in particular, when the opponent is himself hell-bent on flinging vituperation and the like. There is no inconsistency whatsoever in responding with rhetorical harshness to those who are rhetorically harsh, any more than there is in police firing back at bank robbers who fired first. In both cases, self-defense or the defense of others can justify a harsh response.

What I am talking about is the case where your opponent is not being vituperative, but is trying to present you with rational arguments, and instead of responding in kind, you fling abuse at him, attribute bad motives to him, mock him, and otherwise refuse to treat him as a fellow rational agent. This is a kind of violence in the sense I have been describing, insofar as what is by nature good for him, for you, and for the community of rational social animals to which you both belong, is for you to engage with one another at the level of reason, and you are acting in a way that is contrary to that.

Now, blog comboxes, Facebook discussion threads, Twitter feeds, and the like are often snake pits of violence in this sense of the word. In many of them, rational arguments, where they are given voice at all, are met with little more than attributions of bad motives and other ad hominem attacks, mockery, and other forms of sophistry. The irony is that it is often precisely those who most loudly profess to be rational and/or non-violent who are the most prone to this kind of verbal violence. For example, the staunchest opponents of capital punishment and other advocates of non-violence often evince an appalling inability to construct rational arguments, to restrain their emotions, or to refrain from heaping abuse on those who disagree with them. New Atheists and proponents of other forms of self-congratulatory pseudo-rationalism are often guilty of the same.

Further irony can be seen in those prone to accusing others of “micro-aggressions.” If someone calmly attempts to give a rational argument for some conclusion, even a politically incorrect one, that is precisely the opposite of “aggression” or violence, because it is an appeal to reason. And if someone attempts to shut down rational debate because of hurt feelings, that is itself a kind of aggression or violence, precisely because it is contrary to reason.

Then there is the irony of those ostensibly committed to peace and human dignity whose favored tactics are publicly to harass those who disagree with them, to prevent them from speaking, to stir up mob violence, and otherwise to disrupt the law and order that are the precondition of calm and rational discourse.

There is no clearer manifestation of respect for the human dignity of a person with whom one disagrees than to reason with him – and no clearer insult to that dignity than to try to shout him down, intimate him, or otherwise treat him as something incapable or unworthy of rational engagement. Such are the Orwellian times we live in that those who most loudly claim to be against violence are the ones most likely to resort to it.

Related posts:

The voluntarist personality

What is an ad hominem fallacy?

The ad hominem fallacy is a sin

Meta-bigotry

Wrath and its daughters

Published on October 27, 2018 17:07

October 23, 2018

Capital punishment on The Patrick Coffin Show

A few weeks ago I was interviewed by Patrick Coffin on the subject of capital punishment and the recent change to the Catechism. You can now watch the interview either at The Patrick Coffin Show website or at YouTube. If you’re not a regular viewer of Patrick’s show, you should check out his show archives, where you’ll find many interesting guests interviewed and important topics covered.

A few weeks ago I was interviewed by Patrick Coffin on the subject of capital punishment and the recent change to the Catechism. You can now watch the interview either at The Patrick Coffin Show website or at YouTube. If you’re not a regular viewer of Patrick’s show, you should check out his show archives, where you’ll find many interesting guests interviewed and important topics covered. Links to my other recent radio and television interviews can be found at my main website.

Published on October 23, 2018 17:35

October 18, 2018

By Man on radio

Last week on

The Catholic Current

radio show, I was interviewed by Fr. Robert McTeigueabout

By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed

and the recent change to the Catechism’s treatment of capital punishment. The interview lasted an hour and you can listen to the podcast online. Links to other radio and television interviews can be found at my main website.

Last week on

The Catholic Current

radio show, I was interviewed by Fr. Robert McTeigueabout

By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed

and the recent change to the Catechism’s treatment of capital punishment. The interview lasted an hour and you can listen to the podcast online. Links to other radio and television interviews can be found at my main website.

Published on October 18, 2018 23:09

October 12, 2018

The voluntarist personality

A voluntarist conception of persons takes the will to be primary and the intellect to be secondary. That is to say, for voluntarism, at the end of the day what we think reflects what we will. An intellectualist conception of persons takes the intellect to be primary and the will to be secondary. For intellectualism, at the end of the day, what we will reflects what we think. The two views are, naturally, more complicated than that. For example, no voluntarist would deny that what we think affects what we will, and no intellectualist would deny that what we will affects what we think. But the basic idea is that for the voluntarist, the will is ultimately in the driver’s seat, whereas for the intellectualist, the intellect is ultimately in the driver’s seat. The intellectualist is right. That is the view of Aquinas, at any rate, and in an earlier post I argued that voluntarism in a strong version is incompatible with the principle of sufficient reason, and therefore false. Catholic teaching also affirms intellectualism. For example, Pope Leo XIII teaches in his encyclical

Libertas

that:

A voluntarist conception of persons takes the will to be primary and the intellect to be secondary. That is to say, for voluntarism, at the end of the day what we think reflects what we will. An intellectualist conception of persons takes the intellect to be primary and the will to be secondary. For intellectualism, at the end of the day, what we will reflects what we think. The two views are, naturally, more complicated than that. For example, no voluntarist would deny that what we think affects what we will, and no intellectualist would deny that what we will affects what we think. But the basic idea is that for the voluntarist, the will is ultimately in the driver’s seat, whereas for the intellectualist, the intellect is ultimately in the driver’s seat. The intellectualist is right. That is the view of Aquinas, at any rate, and in an earlier post I argued that voluntarism in a strong version is incompatible with the principle of sufficient reason, and therefore false. Catholic teaching also affirms intellectualism. For example, Pope Leo XIII teaches in his encyclical

Libertas

that:the will cannot proceed to act until it is enlightened by the knowledge possessed by the intellect. In other words, the good wished by the will is necessarily good in so far as it is known by the intellect; and this the more, because in all voluntary acts choice is subsequent to a judgment upon the truth of the good presented, declaring to which good preference should be given. No sensible man can doubt that judgment is an act of reason, not of the will.

Similarly, in Humani Generis , Pope Pius XII condemns “innovators” who depart from this doctrine, and who:

indiscriminately mingling cognition and act of will, [say] that the appetitive and affective faculties have a certain power of understanding, and that man, since he cannot by using his reason decide with certainty what is true and is to be accepted, turns to his will, by which he freely chooses among opposite opinions.

And in his famous Regensburg Address, Pope Benedict XVI criticized a voluntarism which:

might even lead to the image of a capricious God, who is not even bound to truth and goodness. God’s transcendence and otherness are so exalted that our reason, our sense of the true and good, are no longer an authentic mirror of God... As opposed to this, the faith of the Church has always insisted that between God and us, between his eternal Creator Spirit and our created reason there exists a real analogy... God does not become more divine when we push him away from us in a sheer, impenetrable voluntarism.

As Benedict’s remarks indicate, that man is by nature a rational animal is what makes it true that we are made in God’s image. Voluntarism is, accordingly, a dehumanizing doctrine. In making of us fundamentally willful animals rather than rational ones, it simply gets human nature wrong. And it makes us out to be essentially “capricious… not even bound to truth and goodness,” all our reasons at bottom just rationalizations of what the will has fixed itself upon. It is an essentially Nietzschean conception of human nature, even if some of its adherents think of themselves as the reverse of Nietzschean.

Intellectualist psychology

“Intellectualism” in the sense in question is, of course, not claiming that all human beings are or ought to be intellectually inclined in the sense of having an interest in philosophy, science, art, or other intellectual pursuits. It merely claims that even the least intelligent human being wills whatever he wills because his mind perceives it to be true or in some way good.

Again, the intellectualist is also not denying that the will can affect the intellect. If you really want to believe in some idea, you might reinforce your confidence in it by focusing your attention on evidence that seems to support it and not letting yourself dwell on evidence against it, and these are acts of the will. You can also avoid dwelling on the fact that you are engaging in such intellectual dishonesty, to the point where you forget that you have done it. The emotional appeal of an idea and/or the painfulness of the thought of its being false can facilitate the will’s resort to such self-deception, insofar as they can distract the intellect from seeing the truth.

But it is still always the intellect that lies at the beginning and end of this process. The will is only drawn to the idea in the first place because the intellectjudges it (however wrongly or confusedly) to be plausible or good, and the end result of the self-deception is that the intellect’s confidence is increased. That increased intellectual confidence is precisely why the will, too, becomes even more attached.

The reason why an irrational person will cover his ears or shout over you or walk away when you have unwelcome evidence or arguments to present to him is precisely because once the intellect sees the truth, it’s “game over” for the will. Though his will is attached to the idea, it will not remain so if his intellect is made to see the evidence against it, and so he tries to avoid seeing it. If the will were really in charge, it could simply push ahead no matter how clearly the intellect saw the will’s object to be false or bad. Rationalization is co-called precisely because the intellect needs to see reasonsfor something before the will can lock on to it – even if what that means is that we are sometimes coming up with reasons not to consider reasons. One of those reasons might even be the intellect’s making the false judgement that “Voluntarism is true anyway!”

As these remarks indicate, even the will of the voluntarist is following what his intellect (wrongly) tells him. The voluntarist may believe that his intellect is subordinate to his will, but he is wrong. Someone who is intellectually convinced of voluntarism may even otherwise think and act very much the way what you’d expect someone to think and act if intellectualism is true. He may be a very rational person, careful always to try to present evidence and arguments for his views, and to consider counterarguments. He may be in no way engaged in self-deception, but simply making an honest mistake. By the same token, someone who is intellectually convinced of intellectualism may otherwise think and act very much the way you’d expect someone to think and act if voluntarism were true. He may be intellectually dishonest or otherwise have poor reasoning skills. A voluntarist can be a rational person, and an intellectualist can be an irrational person.

Psychoanalyzing the voluntarist personality

But let’s consider persons who really do approximate what human beings would be like if voluntarism were true. Some human beings are weak in intellect. Some are very stubborn or willful. Some are prone to excessive emotion. And some (worst of all for them and for those who have to deal with them) are all three. Any of these character defects can so diminish a person’s rationality that it is as if his intellect were subordinate to his will. He might be so in love with a certain idea, or so determined to follow a certain course of action he has decided upon, or so incapable of clear and logical reasoning, that the intellect’s contribution to his behavior is reduced to a minimum. To be sure, it isn’t that his intellect isn’t really still in the driver’s seat. It’s that his intellect is driving blind.

Could it get worse? Yes, if he is so clueless about his condition that he projects it onto others – if he supposes that it isn’t merely that he is like this but that people are like this. He treats others as essentially wills to be opposed or emotionally swayed, rather than as intellects to be rationally persuaded. Call this “the voluntarist personality.” (Note that I’m not talking about voluntarist philosophers themselves now, but rather about people whose personalities approximate what you’d expect people to be like if voluntarism were true.)

The voluntarist personality can, given its willfulness, manifest itself in the amoralism of the libertine or the sociopath. But that is not its typical manifestation. On the contrary, I would suggest that the usual indicator of a voluntarist personality is the opposite extreme tendency, towards a kind of moralism. Since the voluntarist personality sees people primarily as wills rather than intellects, his default position is to judge them as having either good or bad wills rather than as being either correct or incorrect in their judgments. Accordingly, he tends to see those who agree with his opinions as virtuous rather than as merely correct. And he tends to see those who disagree with him as guilty of a moral failingrather than merely making an honest mistake.

It’s the sober middle ground between amoralism and moralism that the voluntarist personality has difficulty achieving. He either disregards morality altogether and just does whatever he wants; or he moralizes everything, making of every cause a crusade and every dispute a witch hunt.

Now, this in turn entails two further tendencies which at first glance seem hard to reconcile but both of which are in fact exactly what one should expect of such a character type. On the one hand, the voluntarist personality tends toward sentimentalismin matters of morality. He is likely to speak excessively of love, mercy, and the like, and very little about moral principle and moral virtue. Moral principle strikes him as too cerebral and too easy for a person to respect even if he has a bad will. Moral virtue, the habitual tendency toward actions that are in line with moral principle, also strikes him as too bloodless, and something someone might exhibit in a rote way or merely because of upbringing, even if his will is bad.

Love, by contrast, is by definition the willing of what is good for someone, and so it can seem to the voluntarist personality to be almost the only thing that really matters. And since he is not too concerned with abstract principle, the way love is expressed is less important to him than the mere expression of it. Hence the voluntarist personality will tend to be overly impressed by mawkish expressions of humanitarian concern, and to be insufficiently attentive to whether this actually results in policies that work. The latter sort of concern seems too technical and intellectual – again, the kind of thing someone might be concerned with even if his will is bad – whereas the expression of noble sentiments seems directly to manifest a good will. The voluntarist personality is also likely to talk excessively of mercy, since he will tend to think that whether a person has a good will is more important than whether his behavior is actually in line with the demands of moral principle.

(Note that I am, of course, not in any way denigrating love, mercy, etc. or denying that someone might outwardly follow the moral law while having bad motives. I am talking about the voluntarist personality’s tendency to oversimplify and put excessive emphasis on these points.)

On the other hand, the voluntarist personality tends toward harshness to those who disagree with him, rather than the love and mercy you might expect from someone so prone to sentimentality. This makes perfect sense psychologically, even if it is odd logically. Again, the voluntarist personality looks at people primarily as wills rather than as minds. So if you disagree with him, he will tend to see this as evidence that you have a bad will, as a moral failing on your part rather than as an honest disagreement. The voluntarist personality thus tends to reply to opponents with ad hominemattacks, and to question the motivesbehind an argument rather than to address the merits of the argument itself. And if what you disagree with, specifically, are what the voluntarist personality regards as his own very refined and noble moral sentiments, he will conclude that you must be very wicked indeed.

Hence, the more moralistic and sentimental the voluntarist personality is, the more likely he is to be hateful and merciless with his enemies. And he will find it difficult to see the inconsistency given his stubborn and emotional nature and his lack of skill at, or patience with, logical reasoning.

Naturally, the voluntarist personality also tends toward fideism. In the religious context, of course, this cashes out to a “will to believe” without evidence, and an impatience with or even hostility toward careful philosophical and theological reasoning or doctrinal consistency. The voluntarist personality who is religious will regard that sort of thing as too bloodless and cerebral. And since he’s not very good at it anyway but nevertheless means well and has strong faith, he judges that it can’t be that important. He will tend to see religion as a matter of the heart more than, or even to the exclusion of, the head.

But someone with a voluntarist personality might also be irreligious, and here his fideism will cash out to a hostility to religion that is so excessive that he finds it difficult to believe that it is even possible for a religious person to have serious arguments to present or to be making an honest mistake. He has absolute faith that arguments for God’s existence and other religious claims can only ever be rationalizations of prejudice, and insists on attacking the motives of the apologist without bothering to try to understand his position. The religious fanatic and the New Atheist are accordingly just two peas from the same voluntarist pod.

In politics, the voluntarist personality’s tendencies are predictable given what has already been said. He will tend to evaluate policy in terms of the motives of those who propose it, and by reference to sentimental and moralistic considerations rather than by way of the dispassionate consideration of arguments and evidence. He will tend to see political opponents as having bad motivations, and thus he is prone to demonizing them.

Since he overemphasizes the will, he will also overestimate what the will can accomplish, and will thus tend in all practical matters to be either excessively optimistic or excessively pessimistic. For example, when most people seem to agree with his political opinions, he will be prone to see this as evidence of a moral advance in society at large, since it will seem to him to indicate that most people have good wills. Great moral progress will seem to be in the offing. On the other hand, when most people disagree with his political opinions, he will be prone to see this as evidence of frightful moral decline, since it will seem to him to indicate that most people have bad wills. Apocalypse will seem to be around the corner. What is difficult for him to see is that sometimes people simply happen to disagree about whether certain policies are workable or wise, and (unlike the voluntarist personality) aren’t necessarily thinking in moralistic terms.

I leave as homework the question of whether this analysis might illuminate what is going on these days in the Catholic Church and in American politics.

Related posts:

Razor boy

Voluntarism and PSR

Cooperation with sins against prudence (and chastity)

Published on October 12, 2018 11:43

October 1, 2018

Caught in the web

Many of you will have heard the awful news already. Longtime blogger Zippy Catholic has died.

Many of you will have heard the awful news already. Longtime blogger Zippy Catholic has died. David Oderberg’s new book Opting Out: Conscience and Cooperation in a Pluralistic Society has just been published by the Institute of Economic Affairs.

At the Daily Intelligencer , the liberal Andrew Sullivan on the dangerously illiberal tendencies currently unfolding within the Democratic Party.

At Five Books, Peter Hacker on the best books on Wittgenstein . The Writing Cooperative on how Isaac Asimov wrote so much. At The American Conservative, Bradley Birzer on Ray Bradbury’s politics. Philip K. Dick’s Man in the High Castle returns for a third season.

Brian Besong’s Manual Recovery Projectaims to bring important Neo-Scholastic manuals of philosophy and theology back into print. Ford and Kelly’s superb two-volume Contemporary Moral Theology is among the works now at last available again.

At Public Discourse, Thomas Pink argues in defense of Catholic integralism.

At Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews, Matthew Kostelecky reviews Michael Gorman’s book on Aquinas and the hypostatic union.

The Claremont Review of Books on René Girard.

Prof. John McAdams and academic freedom have prevailed in the courts over Marquette University. National Review reports .

At Commentary, Gary Saul Morson on atheism and Bolshevik totalitarianism .

Seven things you might not know about F. A. Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom, at FEE.

He replaced one-sided propaganda with… one-sided propaganda. Slateon Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States.

Philosophy and physics are in focus at the website A Pythagorean Universe.

Was John Rawls a socialist? Jacobin investigates .

Barney Hoskyns’ new book Major Dudes: A Steely Dan Companion is reviewed at The Washington Post. Guitarist Jay Graydon on his famous solo on “Peg.”

The Times Literary Supplement on J. L. Austin, philosopher of common sense.

Scientific American on the difficult birth of the “many worlds” interpretation of quantum mechanics.

Also at Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews, Jennifer Frey reviews James Doyle’s new book on Elizabeth Anscombe.

If you’re into ontological investigations, you’ll like the blog Ontological Investigations .

Ars Technica , NPR, and The Daily Beast on the death of Spider-Man co-creator Steve Ditko. Comics writer Chris Ryall reports on some words of wisdom from Ditko: “Anti-clarity… [is] anti-mind.”

The New Atlantis on Errol Morris on Thomas Kuhn.

Where else would we get blog post titles? In defense of puns, at Quartz.

A rare 1990 audio interview with Robert Nozick has been posted at YouTube .

At Time, Heather Mac Donald on how colleges create delusional, thuggish ideologues.

In the National Catholic Register, E. Christian Brugger on the limits of papal authority. In First Things, Russell Hittinger on the Spirit of Vatican I. Jonathan Last reports on the sorry state of the Catholic Church , at The Weekly Standard.

If you’ve only seen the Ant Man movies, you don’t know the whole story. Polygon on the shocking truth about Marvel’s Hank Pym .

Jim Holt on the feud between Gore Vidal and William F. Buckley, Jr., at Lapham’s Quarterly.

The Weekly Standard on John Coltrane and the end of jazz .

Carl Trueman on Aquinas among the Protestants , at Public Discourse.

Loome Theological Booksellers, possibly the oldest theological bookstore in the world, needs your help.

Published on October 01, 2018 18:08

September 27, 2018

Five Proofs on Fox News Radio (Updated)

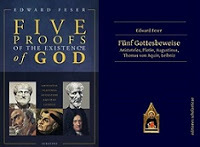

Some time back I was interviewed by Lauren Green about my book

Five Proofs of the Existence of God

for her Fox News Radio show Lighthouse Faith. You can now listen to the podcast online. [UPDATE: If you are having trouble with that link, some other options can be found here and here.]Links to other radio and television interviews and the like can be found at my main website.

Some time back I was interviewed by Lauren Green about my book

Five Proofs of the Existence of God

for her Fox News Radio show Lighthouse Faith. You can now listen to the podcast online. [UPDATE: If you are having trouble with that link, some other options can be found here and here.]Links to other radio and television interviews and the like can be found at my main website.

Published on September 27, 2018 16:53

September 24, 2018

10th anniversary open thread

While there are still a few days left to September, I should note that this month marks the 10th anniversary of this blog. It was initially started in part to serve as a kind of online supplement to

The Last Superstition

, which was published around the same time. Of the eleven books I’ve written, co-written, or edited, seven of them (including TLS) have appeared during the last ten years. We’ll see if I can keep up the pace during the next ten years. Fellow comic book aficionados will have observed that this is also roughly the lifespan of the Marvel Cinematic Universe, and if TLSwas my Iron Man, then perhaps my Infinity War will be my forthcoming book Aristotle’s Revenge: The Metaphysical Foundations of Physical and Biological Science. I am just now putting the finishing touches on it and it should be out by the end of this year or early next year from Editiones Scholasticae. More information to come on that before long.

While there are still a few days left to September, I should note that this month marks the 10th anniversary of this blog. It was initially started in part to serve as a kind of online supplement to

The Last Superstition

, which was published around the same time. Of the eleven books I’ve written, co-written, or edited, seven of them (including TLS) have appeared during the last ten years. We’ll see if I can keep up the pace during the next ten years. Fellow comic book aficionados will have observed that this is also roughly the lifespan of the Marvel Cinematic Universe, and if TLSwas my Iron Man, then perhaps my Infinity War will be my forthcoming book Aristotle’s Revenge: The Metaphysical Foundations of Physical and Biological Science. I am just now putting the finishing touches on it and it should be out by the end of this year or early next year from Editiones Scholasticae. More information to come on that before long. As with the MCU, there is a plan for the future. In case you are curious, next on the agenda are a book on the immortality of the soul, a book on sexual morality, a book on the truth of the Catholic Faith, and a book on Modernism. In that order, though I reserve the right to shift things around or drop something altogether as circumstances change.

In the meantime, it’s a good occasion for another open thread. You know the rules. Keep it civil, keep it classy, but feel free to discuss any topic you wish.

Published on September 24, 2018 17:59

September 20, 2018

Reply to Blackburn on Five Proofs

In the September 7 issue of The Times Literary Supplement, Simon Blackburn reviewed my book

Five Proofs of the Existence of God

. The following response appeared in the TLSletters page in the September 14 issue:Even I will admit that it is not entirely unpleasant to be criticized with the panache and wit that Simon Blackburn brings to the task. All the same, I think he underestimates both the strengths of my position and the weaknesses of his own.

In the September 7 issue of The Times Literary Supplement, Simon Blackburn reviewed my book

Five Proofs of the Existence of God

. The following response appeared in the TLSletters page in the September 14 issue:Even I will admit that it is not entirely unpleasant to be criticized with the panache and wit that Simon Blackburn brings to the task. All the same, I think he underestimates both the strengths of my position and the weaknesses of his own. The broadly Humean epistemology he deploys against the Scholastic theism I defend in Five Proofs of the Existence of God requires a careful balancing act. On the one hand, Blackburn must limit the powers of human reason sufficiently to prevent them from being able to penetrate, in any substantive way, into the ultimate “springs and principles” of nature. For that is the only way to block ascent to a divine first cause – the existence and nature of which, the Scholastic says, follows precisely from an analysis of what it would be to be an ultimate explanation.

These limits have to be even more severe than those that Aristotle, Plotinus, Aquinas and other ancient and medieval philosophical theists would already draw themselves. Precisely because of its ultimacy, the divine cause of things is only barely intelligible to the human mind. Reason’s grasp of it is genuine, but only at the fingertips. Hence Aquinas’s heavy emphasis on the via negativa and the analogical use of language. The intellect gets in just under the wire. To avoid theism, the Humean has to make sure that the intellect doesn’t even get to the wire.

On the other hand, Blackburn has to make sure that this skepticism is not so thoroughgoing that it takes science and Humean philosophy down too, alongside natural theology.

It is one of the key contentions of my book that this balancing trick cannot be pulled off – that to keep reason robust enough to support science and philosophy (even Humean philosophy) as going concerns will inevitably make it robust enough to support Scholastic theism as well.

One way to see this is by way of the principle of sufficient reason, which the Humean must deny. According to the weak version of the principle that I would endorse (which owes more to Aquinas than to the excessive rationalism of Leibniz), all concrete reality is intelligible. Humeans like Blackburn cannot accept the “all” without becoming Scholastic theists. But they cannot replace it with “no” without undermining both science and their own philosophical position. So they must claim that some concrete reality is intelligible and some is not. But where to draw the line, and why there exactly?

No principled answer is forthcoming. Certainly there is no coherent way to draw it, as many atheists attempt to do, at the fundamental laws of nature. Higher-level laws are explained by lower-level laws in something like the way the book on the top of a stack is held up by the ones below it. Take away the floor, and there is nothing that gives the bottom book any power to hold up the top book. Similarly, make the fundamental laws into unintelligible brute facts, and they have no intelligibility to pass upward to higher-level laws – which in turn will have no intelligibility to pass along to the phenomena they are supposed to be explaining. The world’s being just a little bit unintelligible is like its being just a little bit pregnant. Or it is like having a cancer that metastasizes unto the remotest extremity.

Another way to see the problem is by consideration of Hume’s Fork in its contemporary guise – the conceit that if you’re not doing natural science, then the only thing left for you to be doing is “conceptual analysis,” which tells us at best how we have to think about reality, but not how reality itself really is. The trouble with this supposition is that it is itself a proposition neither of natural science nor of conceptual analysis, but rather reflects precisely the third sort of perspective which it alleges to be impossible. Faced with traditional metaphysical claims, the Humean begins with an incredulous stare. But he ends with a coprophagic grin, caught in the very act – metaphysics – he decries as philosophically unchaste.

Blackburn’s playful comparison of a divine first cause to a number ignores the rather crucial difference that numbers are (notoriously) causally inert. This is a little like saying that a living man is like a dead man, except for being living.

In summary, the trouble with Blackburn’s review is that the key questions have not really been addressed. Or rather, they have been begged.

Edward Feser Department of Philosophy Pasadena City College

Published on September 20, 2018 17:07

September 13, 2018

The latest on Catholicism and capital punishment

Recently at Public Discourse, John Finnis defended the thesis that the Catholic Church could adopt the position that capital punishment is intrinsically immoral. Naturally, I disagree with him. My reply to Finnis has now been published at Public Discourse.

Recently at Public Discourse, John Finnis defended the thesis that the Catholic Church could adopt the position that capital punishment is intrinsically immoral. Naturally, I disagree with him. My reply to Finnis has now been published at Public Discourse. At First Things, Catholic theologian Steven A. Long criticizes the “magisterial irresponsibility” of the recent change to the Catechism. Also at First Things, and in an interview with Patrick Coffin, philosopher Michael Pakaluk discusses the relationship between the controversy within the Church over capital punishment and the sex abuse scandal.

Catholic World Report hosts a symposium on capital punishment and the change to the Catechism.

Published on September 13, 2018 17:49

September 9, 2018

The latest on Five Proofs (Updated)

UPDATE 9/16: On Friday I was interviewed about the book on the Stacy on the Right radio show. You can listen to the interview at the show's Facebook page.

UPDATE 9/16: On Friday I was interviewed about the book on the Stacy on the Right radio show. You can listen to the interview at the show's Facebook page.Some months back I was interviewed by Doug Keck of EWTN Bookmark about my book Five Proofs of the Existence of God . The episode airs today on EWTN, and you can also watch it online either at the show’s website or at YouTube.The book has been reviewed in The Times Literary Supplement by atheist philosopher Simon Blackburn, who remains unconvinced. “In spite of Feser’s admirable industry,” he writes, “the whole enterprise does little more than suggest Kant’s description of a dazzling and deceptive illusion.” I have a response to Blackburn forthcoming in TLS.

Five Proofs is also now available in a German translation as Fünf Gottesbeweise , from Editiones Scholasticae.

Published on September 09, 2018 09:48

Edward Feser's Blog

- Edward Feser's profile

- 331 followers

Edward Feser isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.