Edward Feser's Blog, page 55

June 20, 2018

Gödel and the mechanization of thought

At the recent Society of Catholic Scientists conference, Peter Koellner gave a lucid presentation on the relevance of Gödel’s incompleteness results to the question of whether thought can be mechanized. Naturally, he had something to say about the Lucas-Penrose argument. I believe that video of the conference talks will be posted online soon, but let me briefly summarize the main themes of Koellner’s talk as I remember them, so that the remarks I want to make about them will be intelligible. Lucas and Penrose argue that Gödel’s results show that thought cannot be mechanized in the sense of being entirely captured by the algorithmic rules of a Turing machine. It is sometimes supposed that Gödel himself took his Incompleteness results to show this. But as Koellner pointed out, what Gödel actually thought was that the Incompleteness results entail a disjunctive proposition to the effect that eitherthought cannot be mechanized or there are mathematical truths that outstrip human knowledge. Of course, the disjunction is not exclusive. It could be that both disjuncts are true. The point, though, is that Gödel claimed only that his results show that at least one of them must be true. They don’t by themselves tell us which.

At the recent Society of Catholic Scientists conference, Peter Koellner gave a lucid presentation on the relevance of Gödel’s incompleteness results to the question of whether thought can be mechanized. Naturally, he had something to say about the Lucas-Penrose argument. I believe that video of the conference talks will be posted online soon, but let me briefly summarize the main themes of Koellner’s talk as I remember them, so that the remarks I want to make about them will be intelligible. Lucas and Penrose argue that Gödel’s results show that thought cannot be mechanized in the sense of being entirely captured by the algorithmic rules of a Turing machine. It is sometimes supposed that Gödel himself took his Incompleteness results to show this. But as Koellner pointed out, what Gödel actually thought was that the Incompleteness results entail a disjunctive proposition to the effect that eitherthought cannot be mechanized or there are mathematical truths that outstrip human knowledge. Of course, the disjunction is not exclusive. It could be that both disjuncts are true. The point, though, is that Gödel claimed only that his results show that at least one of them must be true. They don’t by themselves tell us which.Another way to think about it is as follows. There is (1) the realm of mathematical truth, (2) the realm of human thought, and (3) the realm of matter. Gödel thought his Incompleteness results show eitherthat the first is irreducible to the second orthat the second is irreducible to the third (or, again, maybe both). But they don’t show which.

It is important to emphasize that what is at issue here is what can be formally demonstrated. Gödel did think that thought cannot be mechanized, but Koellner’s point is that Gödel did not claim that that could be formally demonstrated. He claimed only that the disjunctive statement could be. Was Gödel right about that much? Koellner thinks so. More precisely and cautiously, he thinks that if we confine ourselves to the question of what we can know by way of mathematical truth, and if we work with what he takes to be a plausible formalization of the notion of knowledge, then Gödel can be said to be correct that his disjunction can be formally demonstrated.

Lucas and Penrose claim that the first disjunct of Gödel’s disjunction (to the effect that human thought cannot be mechanized) can also be demonstrated, but Koellner argues that their attempts to show that fail.

There’s more to Koellner’s presentation that that, but this suffices for present purposes. The issue I want to consider is the idea of a formal demonstration of the proposition that human thought cannot be mechanized. Let us grant for the sake of argument that Lucas and Penrose fail to provide such a thing. The question I want to ask is: If thought cannot be mechanized, should we expect to be able to provide a formal demonstration to that effect?

The whole idea seems fishy to me, though it is difficult to point precisely to the reason why. But blogs exist in part for the purpose of airing inchoate or half-baked ideas, so here goes.

For human thought to be mechanized would entail that it could be entirely captured in a formal system. So to give a formal demonstration that thought cannot be mechanized would entail giving a formal demonstration that thought cannot be entirely captured in a formal system. And of course, it would be a human thinker who would be giving this demonstration. It is the conjunction of these elements – the idea of human thought giving a formal demonstration that not everything about human thought can be captured in a formal demonstration – that seems fishy.

But the way that I’ve just stated it is not precise enough to show that there really is any inconsistency or incoherence here. For there is nothing necessarily suspect about the idea of a formal result having implications about the limits of formal results in general – that is what Gödel’s Incompleteness theorems themselves do, after all. And human thinkers are the ones who discover these implications. So what’s the problem?

The problem would be something like this. If you are going to produce a formal result concerning all human thought, it seems that you would first have to be able to formalize all of human thought, so that you would be able to say something about human thought in general in the language of your formal system. But in the case at hand, that means that you would have to be doing for all of human thought – namely, formalizing it – exactly what your purported formal demonstration is supposed to be showing cannot be done. In other words, a formal demonstration to the effect that human thought cannot be mechanized would presuppose that all human thought can be mechanized. In which case the idea is incoherent.

If this is correct, then if human thought cannot be mechanized, then we should expect that we should not be able to give a formal demonstration that it cannot be.

Notice that this does not mean that we should expect not to be able to give a compelling philosophical argument for the conclusion that thought cannot be mechanized. On the contrary, I think there are compelling philosophical arguments to that effect (for example, Kripke’s argument, which is something I talked about in my own SCS talk). The point is rather that we should expect not to be able to give for this conclusion a formal demonstration of the kind familiar from mathematics and formal logic. The limitation in question concerns only that particular kind of argument.

But again, I’m just spitballing here.

Related posts:

Gödel and the unreality of time

Kripke contra computationalism

Accept no imitations [on the Turing test]

Do machines compute functions? Can machines beg the question? From Aristotle to John Searle and Back Again: Formal Causes, Teleology, and Computation in Nature [a 2016 article from the journal Nova et Vetera]

Published on June 20, 2018 09:56

June 14, 2018

The two Cartesian worlds

The “interaction problem” is traditionally regarded as the main objection to Descartes’ brand of dualism. I’ve discussed it many times here at the blog, and of course it is addressed in my book

Philosophy of Mind

. The problem concerns how a res cogitans or “thinking substance” and a res extensa or “extended substance” can possibly have any causal influence on one another given the way Descartes characterizes them. There are various ways the problem might be spelled out. Sometimes it is framed in terms of the idea that it is mysterious how something with no length, width, depth, surface, spatial location, or any other physical attributes (all of which a res cogitans lacks) can get in contact with something that does have such attributes (as a res extensadoes). Sometimes it is framed in terms of the idea that such interaction would violate the law of conservation of energy, insofar as for a res extensato influence a res cogitans would seem to require the physical world as a whole to lose energy, and for causal influence to go in the other direction would seem to require the physical world as a whole to gain energy. As I suggested in a couple of relatively recent posts (here and here), the best way to understand the interaction problem is in terms of the idea that the Cartesian conception of mind and body makes their causal relationship comparable to demonic possession, and cannot account for the unity of the human person.

The “interaction problem” is traditionally regarded as the main objection to Descartes’ brand of dualism. I’ve discussed it many times here at the blog, and of course it is addressed in my book

Philosophy of Mind

. The problem concerns how a res cogitans or “thinking substance” and a res extensa or “extended substance” can possibly have any causal influence on one another given the way Descartes characterizes them. There are various ways the problem might be spelled out. Sometimes it is framed in terms of the idea that it is mysterious how something with no length, width, depth, surface, spatial location, or any other physical attributes (all of which a res cogitans lacks) can get in contact with something that does have such attributes (as a res extensadoes). Sometimes it is framed in terms of the idea that such interaction would violate the law of conservation of energy, insofar as for a res extensato influence a res cogitans would seem to require the physical world as a whole to lose energy, and for causal influence to go in the other direction would seem to require the physical world as a whole to gain energy. As I suggested in a couple of relatively recent posts (here and here), the best way to understand the interaction problem is in terms of the idea that the Cartesian conception of mind and body makes their causal relationship comparable to demonic possession, and cannot account for the unity of the human person.But here’s yet another way to think about it. The Cartesian conception of mind and body, at least when worked out consistently, arguably makes of res cogitans and res extensa two worlds that are so self-contained and complete that there is simply nothing for either one to do vis-à-vis the other. Each is like a fifth wheel relative to the other.

Hence, on the one hand, we have the neo-Cartesian notion of a “zombie” (in the philosophical sense of the term) as the natural consequence of the mechanical conception of matter that Descartes, along with other early modern philosophers and scientists, made central to the modern understanding of nature. I say “neo-Cartesian” because the notion of a zombie is not explicit in Descartes. But it is implicit, and appeal to it has become a key move in the argumentation of contemporary Cartesians. Descartes notoriously thinks of non-human animals, which lack res cogitans, as automata, behaving as if they experience pain, pleasure, and other sensations, but in fact devoid of consciousness. If you add to Descartes’ conception of an animal as an automaton the idea of something which behaves as if it were uttering meaningful speech and as if it were manifesting intelligent behavior but is really just mimicking these things, you essentially have the idea of a zombie – of a creature which is physically and behaviorally identical to a human being but is devoid of any mental properties.

Part of the reason the mechanical conception of matter entails the possibility of zombies is that it takes matter to be devoid of anything like color, sound, taste, odor, heat, cold and the like, as common sense conceives of these qualities. On the mechanical conception, if you redefine redness (for example) as a tendency to absorb certain wavelengths of light and reflect others, then you can say that redness is a real feature of the physical world. But if by “redness” you mean what common sense understands by it – the way red looks in conscious experience – then, according to the mechanical conception, nothing like that really exists in matter. And something similar holds of other sensory qualities. The implication is that matter is devoid of any of the features that make it the case that there is “something it is like” to have a conscious experience, and thus is devoid of consciousness itself.

Another aspect of the mechanical conception of nature that entails the possibility of zombies is the thesis of the causal closure of the physical. The idea here is that everything that happens in the physical world at any one moment of time can be entirely explained in terms of the state of the physical world at an earlier moment of time together with purely physical laws. (Notice that I said explainedby rather than determined by. You don’t need to be a determinist to hold to the causal closure of the physical.) Every physical event, on this view, has a physical cause sufficient to account for it. If this is the case, there is nothing for distinctively mental properties to do, which is why contemporary Cartesians and materialists alike often take an epiphenomenalist position vis-à-vis the mind, according to which mental properties are simply “along for the ride,” as it were, and don’t actually have any efficacy relative to bodily behavior.

The causal closure thesis is arguably the more crucial thesis vis-à-vis zombies, because one could in principle take the view that zombies are possible vis-à-vis phenomenal consciousness but not vis-à-vis rationality. If one did hold this, then one might in principle argue that while there could be a creature physically and behaviorally identical to us that was not conscious, there could not be one that is physically and behaviorally identical to us that was not rational. But if we factor in the causal closure thesis, this becomes untenable. If physical causes suffice to account for everything that happens in the physical world, then that would include apparentlyrational speech activity and apparently rational behavior. Actual rational thought processes qua rational (as opposed to qua physical) would be unnecessary. Hence a zombie devoid even of rationality would be possible.

Then, on the side of res cogitans, we have the Cartesian idea that your mental life could be exactly as it is now even if the entire material world, including your body and brain, were illusory, parts of a hallucinatory deception foisted upon you by a malicious spirit (Descartes’ “evil genius”). This hypothesis reflects what contemporary philosophers of mind would call a radically internalisttheory of mental content, on which the contents of thought and consciousness are determined entirely by factors internal to the mind rather than its relations to anything outside it.

If this radical internalism is correct, then it seems that there is really nothing for the external material world to do vis-à-vis influencing what you think and experience. We have, in effect, the flip side of the zombie hypothesis. On the zombie hypothesis, the world is physicallyidentical to our world, but devoid of phenomenology. On the “evil genius” hypothesis, the world is phenomenologically identical to our world, but devoid of anything physical.

You can see why the Cartesian thesis that some ideas are innate would naturally develop into the thesis that all ideas are innate, as it essentially did in Leibniz (for whom every monad has all information packed into it upon its creation, and thus needs no “window” onto external reality). For if the mind could be in any phenomenological state whatsoever even in the complete absence of matter (and thus the complete absence of any mind-independent world or any sense organs with which to make contact with a mind-independent world) then what is needed in order to determine the content of any phenomenological state (and thus any thought or experience) must already be built into the mind.

So, again, the Cartesian picture of reality leaves us with two self-contained worlds. There is physical reality, which could be exactly as it is in the complete absence of any mental phenomena whatsoever, as in the zombie scenario. And there is mental reality, which could be exactly as it is in the complete absence of any physical phenomena whatsoever, as in the evil genius scenario. So what exactly does matter do vis-à-vis mind, and what exactly does mind do vis-à-vis matter? Interaction becomes problematic because it seems unnecessary.

This also helps us also to understand more deeply why, as I have often pointed out, there is no interaction problem on an Aristotelian-Thomistic (A-T) conception of human nature, even though it too regards the intellect as immaterial. For one thing, the A-T position rejects the thesis of the causal closure of the physical. And the main reason it does so is because the causal closure thesis conceives of causation entirely in terms of what A-T thinkers would call efficient causality. But efficient causality is only one of four fundamental modes of explanation – the others being, of course, formal causality, material causality, and final causality. The causal closure thesis also presupposes a reductionist conception of physical objects (never mind the immateriality of the intellect) that the A-T position rejects. It just gets the basic metaphysics even of the material worldbadly wrong. And of course, from an A-T point of view, the Cartesian also gets the metaphysics of human nature badly wrong, starting with the idea that a human being is a mashup of two distinct substances. There simply aren’t two things in the case of a human being in the first place, on the A-T view, and thus there is no question of how two things “interact.”

Nor does the A-T position have any truck with the internalism and innatism of the Cartesian position, committed as A-T is to the thesis that “there is nothing in the intellect that was not first in the senses.” Angels have innate ideas, but we don’t. For example, we need to abstract our ideas of universals like dog, tree, man, etc. from actual concrete particular material things which instantiate those universals – in which there must be concrete particular material things in order for us to have any ideas about them. Hence there is no sense to be made of our having exactly the phenomenology we have in the absence of any material world.

(Does that mean that angels could be subject to an “evil genius” type hallucination? No, because Descartes’ scenario involves a kind of sensory experience, and angels don’t have that. In fact it is not clear that, given A-T premises, we can really make coherent sense of the evil genius scenario. For the scenario involves sensory experience in the complete absence of anything corporeal. But if there is no corporeality, there can be no sensory experience; and if there is sensory experience, then there must be corporeality. The scenario seems possible only if we don’t think about the underlying metaphysics very carefully.)

Published on June 14, 2018 16:47

June 6, 2018

Talk amongst yourselves

We’re due for another open thread, so here goes. That threadjacking comment of yours from two weeks ago that got deleted? Repost it here, where it will be welcome and on topic. ‘Cause whether its ontology or mixology, Ed Wood or the Form of the Good, Saul Bellow or Yello, everything’s on topic. As always, keep it classy and troll-free. Previous open threads can be viewed here.

We’re due for another open thread, so here goes. That threadjacking comment of yours from two weeks ago that got deleted? Repost it here, where it will be welcome and on topic. ‘Cause whether its ontology or mixology, Ed Wood or the Form of the Good, Saul Bellow or Yello, everything’s on topic. As always, keep it classy and troll-free. Previous open threads can be viewed here.

Published on June 06, 2018 17:10

May 28, 2018

Musical chairs brains minds

Comics, like science fiction, can be a great source for philosophical thought experiments. Recently I’ve been re-reading one of the classic Marvel storylines from the 1970s, the “Headmen saga” from The Defenders, by Steve Gerber and Sal Buscema. Gerber, who was among the best writers ever to have worked in comics, famously specialized in absurdist satire, and this storyline is a prime example. More to the present point, it contains an interesting twist on a scenario familiar from discussions of the philosophical problem of personal identity. The Defenders, at this point in the series, include Dr. Strange, the Hulk, Valkyrie, Luke Cage – all of whom will be familiar to viewers of the Marvel movies and Netflix series – and Nighthawk (pictured at left above), a reformed criminal and heir to a fortune, who bankrolls the team. Staying with them is their friend Jack Norriss, the husband of Valkyrie – or rather, of Barbara Norriss, the woman whose body Valkyrie is occupying. (It’s complicated.)

Comics, like science fiction, can be a great source for philosophical thought experiments. Recently I’ve been re-reading one of the classic Marvel storylines from the 1970s, the “Headmen saga” from The Defenders, by Steve Gerber and Sal Buscema. Gerber, who was among the best writers ever to have worked in comics, famously specialized in absurdist satire, and this storyline is a prime example. More to the present point, it contains an interesting twist on a scenario familiar from discussions of the philosophical problem of personal identity. The Defenders, at this point in the series, include Dr. Strange, the Hulk, Valkyrie, Luke Cage – all of whom will be familiar to viewers of the Marvel movies and Netflix series – and Nighthawk (pictured at left above), a reformed criminal and heir to a fortune, who bankrolls the team. Staying with them is their friend Jack Norriss, the husband of Valkyrie – or rather, of Barbara Norriss, the woman whose body Valkyrie is occupying. (It’s complicated.)Their nemeses the Headmen are basically a cabal of crackpot central planners who seek to remodel society so as to remove from it any element of arbitrariness or accident. Their leader is Dr. Arthur Nagan (also pictured above), a transplant surgeon whose head has been grafted on to the body of a gorilla. Assisting him is Dr. Jerry Morgan, a researcher in cell biology who accidentally shrunk the bones of his face so that the skin hangs droopily and grotesquely from it. Then there is Harvey Schlemerman, who goes by the alias Chondu the Mystic – a third-rate Dr. Strange wannabe whose incomplete mastery of sorcery never got him much farther than the carnival circuit. Rounding out the team is Ruby Thursday, a computer scientist who has replaced her head with a shape-shifting supercomputer that usually takes the form of a shiny red sphere, but is capable of taking on any other appearance or configuration she desires.

Competing with the Headmen for world domination is Nebulon, an extremely powerful Adonis-like extraterrestrial whose own scheme for takeover of the Earth involves masquerading as a balding middle-aged self-help guru. Teaming up with the Ludberdites, another extraterrestrial race – of reptilian scientist-philosophers who believe themselves obligated to bring inferior races to enlightenment – Nebulon founds the Celestial Mind Control human potential movement. The cult-like movement (whose members wear Bozo the Clown masks to represent the mediocre selves they hope to move beyond) soon gains a mass following, especially in France. There’s also a mysterious gun-toting elf who seems to have nothing to do with any of the parties to the conflict, but who randomly appears at various points in the story, shoots someone, then disappears.

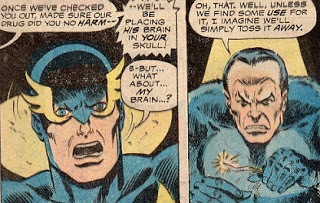

Well, again, it’s complicated (and often pretty funny) – very “70s”-ish both in its weirdness and in the objects of its satire. Anyway, the part of the tale that primarily concerns us is this. In order to infiltrate the Defenders, the Headmen kidnap Nighthawk, remove his brain, and transplant Chondu’s brain into Nighthawk’s body. Nighthawk’s brain is then placed in a bowl of life-preserving chemicals – where, cut off from all sensory stimulation, it proceeds to hallucinate for a big chunk of the story. Eventually the Defenders figure out what is going on, and in order to trick the Headmen and retrieve Nighthawk’s brain, Dr. Strange casts a spell that transfers Jack Norriss’s mind into Chondu’s brain, which is still in Nighthawk’s body. Chondu’s mind is in turn transferred into the body of a fawn which the Hulk calls “Bambi” and had brought into the Defenders’ headquarters as a pet. Jack’s body, now mindless (but not lifeless), is left on a slab, awaiting the return of Jack’s mind once the scheme is completed.

Needless to say, there is a lot of fodder here for the philosopher interested in questions of identity. Some of the story elements involve scenarios familiar from the philosophical literature on personal identity: the transfer of consciousness from one body to another, the transplant of a brain from one body to another, the replacement of a brain with a computer, and the “brain in a vat” scenario. The idea of a human consciousness entering the body of an animal is also familiar from discussions of reincarnation. But Gerber adds a novel twist with the case of Jack’s mind in Chondu’s brain in Nighthawk’s body. Quite a mess!

Could a swap of bodily and non-bodily parts get any more complex than that? It could, with a scenario entertained by John Locke, which perhaps Gerber would have been tempted to incorporate into his story if he’d thought of it. In the Essay Concerning Human Understanding, Locke argues that personal identity cannot reduce to sameness of body over time, because it is at least possible in principle, he argues, for a person’s consciousness to jump from one body to another (as in his famous prince and cobbler scenario). But he argues that personal identity also cannot reduce to sameness of immaterial substance or soul over time, because (so Locke claims) a person’s consciousness could in principle jump from one immaterial substance to another just as it could jump from one body to another.

So, imagine a case where Dr. Strange first somehow transfers Jack’s consciousness into (say) the Hulk’s immaterial substance or soul, and then transfers that soul into Chondu’s brain which is in Nighthawk’s body. Then we’d have: Jack’s consciousness in the Hulk’s soul in Chondu’s brain in Nighthawk’s body. An even bigger mess! Who would the resulting person be? Locke’s answer, of course, would be that it is Jack. That is the point of his various thought experiments. He thinks that continuity of consciousness, rather than continuity of either a physical or non-physical substance, is the key to personal identity.

Is any of this really possible even in principle, though? That depends, of course, on the background metaphysics one brings to bear on the subject. The proposed scenario Locke added to the discussion (the jump of consciousness from one soul to another) in fact doesn’t really make any sense given the main traditional philosophical conceptions of the soul. Locke seems to think of a soul as a kind of vehicle or container with a separable content – namely various particular thoughts, memories, experiences, and the like. He supposes that this container might be emptied of its contents and new contents (or perhaps no contents at all?) put in place of them.

But that is not how Descartes (say) understands the soul. For Descartes, the soul is a res cogitans or thing that thinks, and that is its entire nature. That is to say, he doesn’t think of the soul as something that merely has thinking as an activity, but rather as something that just is thinking. There is nothing more to it than that. Hence there would, for him, be no sense to be made of somehow separating the thinking of (say) your soul from your soul itself, and putting some other thoughts into it. There is no gap between the soul and its activity or content by which this would be possible. Hence for Descartes, Locke’s scenario would be a non-starter.

Nor is it clear, in any case, what it would mean for a consciousness to jump from one soul to another. A thought, experience, memory, or the like is a kind of attribute of the person who has it. In this respect, at least, it is like a person’s being fat or being tall. Now, it makes no sense to think of your tallness or fatness jumping from you to another person. Of course, another person could have the same height as you and thus be as tall as you are. But that just means that your tallness and his tallness are similar, not that they are numerically identical. Even if he started out short and grew, and at the same time you shrank, that would not be a matter of your tallness jumping from you to him (whatever that would mean). It would just be a matter of your losing your tallness and his gaining his own tallness. In the same way, what would it mean for your memory of high school, or your personality trait of being short-tempered, to jump from your soul to his?

Even to common sense, the idea that a consciousness could jump from one soul to another sounds very weird. The commonsense notion of the soul – or at least, the notion familiar from modern pop culture (movies, etc.) – seems to identify it precisely with consciousness considered as a kind of substance in its own right. Descartes’ conception could be regarded as a refinement of this common conception. (There is another commonsense way of thinking about the soul, however – though perhaps more common in ancient times than in modern times – on which it is a kind of animating principle. Aristotle’s idea of the soul as the form of the body would be a philosophical refinement of this notion.)

Given that this is the usual commonsense understanding, it probably didn’t even occur to Gerber (who obviously wanted to make his scenario as weird and complicated as possible) to add a further, Lockean “soul swap” element to his Jack/Chondu/Nighthawk mashup. But what he does put into that mashup would certainly be possible from a Cartesian point of view. Descartes would say that what Dr. Strange did was causally to correlate Jack’s res cogitans with a bit of res extensathat had once been in Chondu’s body (viz. Chondu’s brain) but which is now in turn causally correlated with the bulk of the res extensa that is Nighthawk’s body. Chondu’s res cogitans, in turn, was causally correlated by Dr. Strange with the body of Bambi (the Hulk’s pet fawn).

(Just to make things more complicated, it might be worth noting that for Locke, it seems, the Chondu-to-Bambi switch would notbe possible. The reason is that though Locke is a kind of property dualist, he thinks that matter must be “fitly disposed” before thought can be “superadded” to it. In other words, while a complex arrangement of matter is not a sufficientcondition for a physical thing’s being able to think, it is in Locke’s view a necessary condition. Since Bambi is not a rational animal, I imagine Locke might say that her matter is not fitly disposed to be associated with thought, so that Chondu’s intellect could not come to be associated with it. See my book Locke for further discussion of Locke’s position.)

From an Aristotelian-Thomistic (A-T) point of view, much of what Gerber describes is not possible even in principle. For Aristotle and Aquinas, your soul is the form of your body, so that anything that had your soul would of necessity be your body (or at least part of your body – more on that qualification in a moment). Hence it would be impossible for Valkyrie’s soul to enter Barbara’s body (since Valkyrie’s soul is the form of Valkyrie’s body), or for Chondu’s soul to enter Bambi’s body (since Chondu’s soul, being the form of Chondu’s body, is the form of a human body), or for Jack’s soul to enter Chondu’s brain (since Jack’s soul, being the form of Jack’s body, could only ever be associated with Jack’s brain). Nor would it be possible for Jack’s body to survive in the absence of Jack’s soul. Given the A-T view of the soul, for the body to lose its soul is for it to lose the form of a living thing, and thus to cease being a living thing.

However, the Chondu-to-Nighthawk brain swap does not seem impossible in principle from an A-T point of view. It would seem to be continuous with heart transplants, lung transplants, etc. Chondu, in effect, would be getting a full-body transplant. The scenario does, however, raise interesting questions about how to work out the details of the A-T position. Nighthawk’s soul is the form of his body. More precisely, it is a substantial form, that which makes the matter of Nighthawk’s body to be a substance of the kind it is. Now, immediately after Nighthawk’s brain is removed from the body, it is clear enough that the same soul (Nighthawk’s) is still giving form to the matter that makes up his body, even though the matter has now been severed into two parts (the brain and the rest of the body). This is like the case where a finger or the like is severed and then reattached surgically. The circumstances are not the normal ones by which a soul gives form to the matter of the body, but the same principle applies even though the parts are separated. Nor does the fact of there being two spatially separated bits of matter show that there are now two substances, because the severed finger is not a complete substance in the first place. It is ordered to the rest of the body. That is its natural home, as it were, and its identity conditions reflect that fact even when it is unnaturally separated from it.

But the Chondu brain swap complicates things. Once Chondu’s brain is attached to Nighthawk’s body and starts to control it, whose soul is giving form to the matter of Nighthawk’s body? Chondu’s or Nighthawk’s? I am inclined to say that it depends on whether the body resists the transplant and on how long the brain stays in this new body. Suppose the body resists the transplant and/or that the brain does not stay in the body long enough for the surgical wounds fully to heal or the integration to become complete and natural. In that case I would argue, tentatively, that it is still Nighthawk’s soul that is giving form to the matter of the body, even though Nighthawk’s brain is in a bowl somewhere and the body has got someone else’s brain in it. For it is at this point still essentially functioninglike Nighthawk’s body rather than Chondu’s body (by resisting the transplanted brain and/or not integrating smoothly with it).

Suppose, however, that the transplant “takes,” the wounds heal, and the integration becomes smooth, “second nature” as it were. Then I would say that Chondu’s brain would in that case essentially have assimilated Nighthawk’s body to itself, in something remotely analogous to the way the body integrates food into itself after a meal. And in that case Chondu’s soul would effectively take over the job of giving form to the matter that had once been Nighthawk’s body.

Perhaps an even trickier case is Ruby Thursday. Again, she has replaced her head (and thus her brain) with a malleable computer. The rest of the original body remains, however. (And Ruby is actually quite an attractive woman – well, apart, that is, from having a head like a red bowling ball.)

Now, on the one hand, from an A-T point of view, computers cannot be said to think, in part because a thinking thing is a kind of natural substance, and a computer is not a natural substance, but a kind of artifact. So, you might conclude from that that strictly speaking, Ruby post-transplant no longer really exists – that what is left is essentially a body artificially kept alive and controlled by an unconscious, unthinking mechanism.

However, the A-T position does not rule out the possibility of prosthetic organs being integrated into a body, as in the case of an artificial heart. It’s hard to see why that would not include artificial neural parts, such as computer components integrated into a brain in order to restore lost functionality. On the A-T view, after a heart transplant you would remain the same person – the same soul-body composite – after the transplant as you were before, and the A-T view would also imply that this situation would not change if what you received was a transplant of artificial neural structures rather than an artificial heart.

So far, so good. But the Ruby Thursday example is harder to interpret. On the one hand, you could argue that since most of her original body remains, what has happened is that the same organism (namely the human being or rational animal Ruby Thursday) survives the transplant, and that the artificial computer brain is analogous to an artificial heart. Ruby, on this interpretation, would still be a conscious, rational creature, merely using a prosthetic organ to take in information about her body and the external environment, to generate perceptual experiences and phantasms that her intellect can abstract from, and so forth.

On the other hand, as my treatment of the Chondu-Nighthawk example indicates, the brain does seem to be more central to the organism than other body parts are, so that one could argue instead that with the original brain completely destroyed, Ruby’s spherical replacement is not properly thought of as a prosthetic, but just as an unliving mechanism. The rest of Ruby’s body, on this interpretation, would be analogous to a kidney or heart that has been removed from a corpse and kept alive. No one thinks that keeping a kidney or heart alive suffices to keep the person alive. And on the interpretation of the Ruby Thursday example that I’m now entertaining, the part of Ruby’s body that survives the loss of her original brain and head is like the kidney or heart. It isn’t really her anymore.

I’ll leave that interpretive issue unresolved for now. And I haven’t even mentioned how much weirder the Chondu situation gets later in the story. While his brain is in Nighthawk’s body, Nagan and the other Headmen decide radically to alter Chondu’s body, giving him a unicorn horn, a serpentine tongue, gigantic bird-like legs and bat-like wings, and a bundle of lampreys in place of each arm. The motive, apparently, was to see how far Nagan could push his transplant techniques. Naturally, Chondu was not thrilledabout this upon awakening after the surgery that restored his brain to this modified body!

In case any readers are interested, the Defenders-Headmen saga has been collected in a one-volume hardcover edition, and is also available in a very cheap Kindle version.

Related posts:

What is a soul?

The metaphysics of The Fly

Two, four, six, eight! Who do you reincarnate? Self control

You’re not who you think you are

Pop culture roundup

Published on May 28, 2018 17:23

May 20, 2018

The Church permits criticism of popes under certain circumstances

Fathers have the authority to teach and discipline their children, but this authority is not absolute. They may not teach their children to do evil, and they may not discipline them with unjust harshness. Everyone knows this, though everyone also knows that there are fathers who do in fact abuse their children or teach them to do evil. Everyone also knows that it is right for children under these unhappy circumstances to disobey and reprove their fathers, while still acknowledging their fathers’ authority in general and submitting to his lawful instructions. All the same, probably no father ever says to his children: “Children, here’s what to do if I ever start to abuse you or teach you to do evil.” The reason for this is surely that the default assumption is that children will never need to know what to do under such circumstances, and that explicitly addressing it in this way would give them a false and disturbing impression. Children might start to wonder whether abuse or evil teaching is a likely prospect, and for that reason come to doubt their father’s wisdom and good will.

Fathers have the authority to teach and discipline their children, but this authority is not absolute. They may not teach their children to do evil, and they may not discipline them with unjust harshness. Everyone knows this, though everyone also knows that there are fathers who do in fact abuse their children or teach them to do evil. Everyone also knows that it is right for children under these unhappy circumstances to disobey and reprove their fathers, while still acknowledging their fathers’ authority in general and submitting to his lawful instructions. All the same, probably no father ever says to his children: “Children, here’s what to do if I ever start to abuse you or teach you to do evil.” The reason for this is surely that the default assumption is that children will never need to know what to do under such circumstances, and that explicitly addressing it in this way would give them a false and disturbing impression. Children might start to wonder whether abuse or evil teaching is a likely prospect, and for that reason come to doubt their father’s wisdom and good will. Hence, in the typical case, what to do in such a situation is left implicit and vague. The nature of paternal authority is such that this is the way things should be. Because the presumption that fathers will not abuse their authority is so strong, and because children need to believe viscerally that this is extremely unlikely to happen, the matter almost never comes up in most families. There is a downside, of course, which is that on those rare occasions when a father does abuse his authority, children are bound to be confused about how to deal with the situation. What do you do when the man appointed by nature to be your primary teacher and guardian starts to mislead or harm you?

Now, the papacy is like this. The Church has no official and explicitly stated policy about how to deal with a pope who teaches error or otherwise abuses his office. That is not because such error and abuse are not possible. On the contrary, not only has the Church always allowed for the possibility that a pope can teach error when not speaking ex cathedra and that he can make policy decisions that do grave harm to the faithful, but both of these things have in fact happened on a handful of occasions – for example, the doctrinal errors of Pope Honorius I and Pope John XXII, the ambiguous doctrinal formula temporarily accepted by Pope Liberius, the Cadaver Synod of Pope Stephen VI and its aftermath, and the mistakes of Pope Urban VI that contributed to the Great Western Schism. (I have discussed these cases here, here, and here.)

But there is in Catholic theology so strong a presumptionagainst a pope making grave doctrinal and disciplinary errors that, as with a father in relation to his children, it would be potentially misleading and destabilizing explicitly to formulate a policy concerning what to in such a situation. Hence you won’t find in the Catechism a section on what to do about a bad pope. The very existence and expression of such a policy might give the false impression that bad popes are bound to arise with some regularity.

The downside is that on those rare occasions when a bad pope does come along, the Church is bound to be flummoxed. Many Catholics without theological expertise will wrongly suppose that a Catholic must absolutely always support any policy that a pope implements, or assent to any doctrinal statement that a pope issues – even when such a statement seems manifestly contrary to traditional teaching (as in the cases of Honorius I and John XXII). This will lead to one of two outcomes, depending on the capacity of such ill-informed Catholics for cognitive dissonance.

Those who are more prone to react emotionally and less capable of clear and logical reasoning – and thus who are comfortable with embracing contradictions – will tend to go along with the doctrinal or policy errors of such a pope. Their own understanding and practice of the Faith is going to be impaired as a result. They are also bound to sow discord in the Church, since they will likely accuse those Catholics who do not embrace the errors of disloyalty and dissent. By contrast, those who cannot bear such cognitive dissonance are liable to have their faith shaken. They will wrongly suppose that they are obliged to assent to the errors, but find that they are unable to do so given the manifest conflict with traditional teaching. They will needlessly worry that this conflict between current and past teaching falsifies the Church’s claim to indefectibility.

It is important, then, for Catholics to realize that the traditional teaching of the Church has always allowed for the possibility of criticism of a pope who teaches error. Indeed, such an acknowledgment is there in the New Testament, in St. Paul’s famous public rebuke of St. Peter for conduct that “seemed to indicate a wish to compel the pagan converts to become Jews and accept circumcision and the Jewish law” (as the Catholic Encyclopediacharacterizes Peter’s scandalous action).

It is also manifest in the condemnation of Pope Honorius I by his successors Pope St. Agatho and Pope St. Leo II. It is evident in Pope Innocent III’s statement: “Only on account of a sin committed against the faith can I be judged by the church” (quoted in J. Michael Miller, The Shepherd and the Rock: Origins, Development, and Mission of the Papacy, at p. 292). It is reflected in the example of the 14th-century theologians who criticized the doctrinal error of Pope John XXII, criticism which led to his recantation. It is obvious from the extremely negative judgments that devout Catholic historians (such as many of the authors of the Catholic Encyclopedia) have made about the worst popes. And though you don’t find the subject raised in the Catechism, the Church under Pope St. John Paul II in fact addressed the possibility of legitimate disagreement explicitly and at some length.

The teaching of Donum Veritatis

This may seem surprising given that John Paul II and his chief doctrinal officer Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI) have a reputation for disciplining dissenting theologians such as Hans Küng and Charles Curran. However, as I explained in an earlier post, and as Joe Bessette and I explain in much greater detail at pages 144-57 of By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed , various teaching documents issued during the last several decades make it clear that there are five categories of magisterial statement. The first two categories (which concern divinely revealed dogmas and logical implications of dogmas, respectively) require unconditional assent on the part of Catholics; the third category (which concerns non-irreformable but still binding theological and moral teaching) entails a very strong presumption of assent; the fourth (which concerns prudential disciplinary directives) requires only obedience in behavior but not assent; and the fifth (which concerns prudential application of theological or moral principle to contingent circumstances) requires neither obedience nor assent but merely respectful consideration.

Moreover, the Instruction Donum Veritatis , issued by the CDF under Cardinal Ratzinger, makes it clear that not all disagreement with the Magisterium of the Church constitutes dissent of the objectionable kind that Küng, Curran, et al. are guilty of. Here are the relevant passages, from sections 24-32:

The willingness to submit loyally to the teaching of the Magisterium on matters per se not irreformable must be the rule. It can happen, however, that a theologian may, according to the case, raise questions regarding the timeliness, the form, or even the contents of magisterial interventions…

When it comes to the question of interventions in the prudential order, it could happen that some Magisterial documents might not be free from all deficiencies. Bishops and their advisors have not always taken into immediate consideration every aspect or the entire complexity of a question…

Even when collaboration takes place under the best conditions, the possibility cannot be excluded that tensions may arise between the theologian and the Magisterium… If tensions do not spring from hostile and contrary feelings, they can become a dynamic factor, a stimulus to both the Magisterium and theologians to fulfill their respective roles while practicing dialogue…

The preceding considerations have a particular application to the case of the theologian who might have serious difficulties, for reasons which appear to him wellfounded, in accepting a non-irreformable magisterial teaching…

If, despite a loyal effort on the theologian's part, the difficulties persist, the theologian has the duty to make known to the Magisterial authorities the problems raised by the teaching in itself, in the arguments proposed to justify it, or even in the manner in which it is presented. He should do this in an evangelical spirit and with a profound desire to resolve the difficulties. His objections could then contribute to real progress and provide a stimulus to the Magisterium to propose the teaching of the Church in greater depth and with a clearer presentation of the arguments…

For a loyal spirit, animated by love for the Church, such a situation can certainly prove a difficult trial. It can be a call to suffer for the truth, in silence and prayer, but with the certainty, that if the truth really is at stake, it will ultimately prevail…

[T]hat public opposition to the Magisterium of the Church also called “dissent”… must be distinguished from the situation of personal difficulties treated above.

End quote. There are several important points made in these passages. First, what is in view here is the possibility of legitimate criticism of “teaching[s] of the Magisterium on matters per senot irreformable” – which would include magisterial statements even in the third category referred to above, as well as the fourth and fifth categories. As the instruction notes, assent to such statements “must be the rule,” but this strong presumption of assent can be overridden. How?

As I argued in a recent Catholic World Report article, Catholic teaching concerning the reliability of the ordinary magisterium of the Church implies that if the Church has consistently taught some doctrine for centuries, that teaching cannot be considered reformable. This is why liberal theologians who question the Church’s traditional teaching on matters such as contraception or the ordination of women do not have a leg to stand on. When the Magisterium is simply reiterating such traditional teaching, disagreement cannotbe justified by appeal to these passages from Donum Veritatis.

Rather, as theologian William May notes, legitimate disagreement of the kind the Instruction has in view is most plausible when theologians “can appeal to other magisterial teachings that are more certainly and definitively taught with which they think the teaching questioned is incompatible” (An Introduction to Moral Theology, Revised edition, p. 242). In other words, the possibility of legitimate criticism of a magisterial statement is most plausible precisely when that statement seems to conflict with long-standing past teaching, and not when it merely reiterates long-standing past teaching.

There are, after all, strict limits on what the Church and the popes can teach, as the Church and the popes have themselves constantly affirmed. For example, the First Vatican Council teaches:

For the Holy Spirit was promised to the successors of Peter not so that they might, by his revelation, make known some new doctrine, but that, by his assistance, they might religiously guard and faithfully expound the revelation or deposit of faith transmitted by the apostles.

Similarly, the Second Vatican Council teaches:

[T]he living teaching office of the Church… is not above the word of God, but serves it, teaching only what has been handed on, listening to it devoutly, guarding it scrupulously and explaining it faithfully.

And Pope Benedict XVI taught:

The Pope is not an absolute monarch whose thoughts and desires are law. On the contrary: the Pope's ministry is a guarantee of obedience to Christ and to his Word. He must not proclaim his own ideas, but rather constantly bind himself and the Church to obedience to God's Word, in the face of every attempt to adapt it or water it down, and every form of opportunism.

End quote. So, suppose some papal statement or other magisterial document didappear to try to introduce “some new doctrine,” or appeared to “water down” the Church’s consistent past teaching, or failed to guard that teaching “scrupulously” or to explain it “faithfully.” This would be the clearest possible case in which a theologian might raise legitimate criticisms of the kind recognized by Donum Veritatis.

A second important point to note from the passages quoted is that Donum Veritatis affirms that a theologian not only can have the right to raise objections, but in some cases even “has the duty to make known to the Magisterial authorities the problems raised by the teaching in itself, in the arguments proposed to justify it, or even in the manner in which it is presented.” Indeed, the document teaches that a theologian’s “objections could then contribute to real progress” and “a stimulus to both the Magisterium and theologians to fulfill their respective roles.” In other words, the Church doesn’t merely tolerate criticism under circumstances like the ones in question, but acknowledges that such criticism can be a good thing and a service to the Magisterium.

A third and quite remarkable acknowledgement in these passages from Donum Veritatis is that for the theologian who raises such legitimate criticisms, “such a situation can certainly prove a difficult trial. It can be a call to suffer for the truth.” In other words, the Church explicitly acknowledges the possibility that a non-infallible act of the Magisterium can be so defective that it is the theologian who respectfully criticizes that act who is upholding “the truth,” so that this defective magisterial act is something from which the theologian will unjustly “suffer.”

A fourth point that must be emphasized is that Donum Veritatis explicitly says that legitimate criticism of deficient magisterial statements does not constitute “dissent” from Church teaching, as that term is usually understood. As the document goes on to explain in some detail, what the Church condemns as “dissent” has to do instead with “attitudes of general opposition to Church teaching” of the kind which arose after Vatican II. This spirit of dissent, Donum Veritatis says, has the following characteristics:

• It stems from “the ideology of philosophical liberalism, which permeates the thinking of our age,” and which pits “freedom of thought” against “the authority of tradition.”

• It regards “teaching handed on and generally received [as] a priori suspect” and claims that “doctrines proposed without exercise of the charism of infallibility… have no obligatory character about them, leaving the individual completely at liberty to adhere to them or not.”

• It often assigns a “normative value” to “models of society promoted by the ‘mass media’,” is influenced by “the weight of public opinion,” and seeks to limit magisterial statements to topics “which public opinion considers important and then only by way of agreeing with it.”

• “In its most radical form, it aims at changing the Church following a model of protest which takes its inspiration from political society.”

Clearly, then, the “dissent” that Donum Veritatiscriticizes is the kind that is motivated by the theological liberalism of Küng, Curran, et al., which wants the Church to abandon traditional teaching and conform herself to the values prevailing in modern secular liberal society. A theologian who criticized a pope for failing to reiteratetraditional teaching (as the medieval theologians who criticized Pope John XXII did) would therefore be the oppositeof a “dissenter.”

A fifth point to emphasize is that the criticism allowed by Donum Veritatis can be expressed publicly. Speaking at a press conference about a hypothetical theologian who raises the sorts of legitimate criticism allowed by Donum Veritatis, Cardinal Ratzinger said: “We have not excluded all kinds of publication, nor have we closed him up in suffering” (quoted in Anthony J. Figueiredo, The Magisterium-Theology Relationship, at p. 370). As William May notes:

The Instruction obviously considers it proper for theologians to publish their “questions,” for it speaks of their obligation to take seriously into account objections leveled against their views by other theologians and to revise their positions in the light of such criticism – and this is normally given only after a theologian has made his questions known by publishing them in professional theological journals. (AnIntroduction to Moral Theology, pp. 241-42)

Similarly, Cardinal Avery Dulles notes that Donum Veritatis“does not discountenance expression of one’s views in a scholarly manner that might be publicly reported” (The Craft of Theology, p. 115).

This is a crucial point. Some Catholics have falsely claimed that Donum Veritatis only permits criticism that is expressed privately to the relevant Church authorities. Their basis for thinking this is a remark in the Instruction to the effect that “the theologian should avoid turning to the ‘mass media’, but have recourse to the responsible authority.” But as Cardinal Ratzinger’s statement makes clear, Donum Veritatis in fact does notprohibit all publicly expressed criticism. Furthermore, the remark about “mass media” has to be read in context, because the Instruction addresses the topic of mass media in several places, and seems concerned to criticize a very specific aspectof modern mass media, rather than the use of mass media as such. The longer passage from which the words just quoted are taken reads as follows:

[T]he theologian should avoid turning to the "mass media", but have recourse to the responsible authority, for it is not by seeking to exert the pressure of public opinion that one contributes to the clarification of doctrinal issues and renders service to the truth.

End quote. And in the context of discussing the baneful influence of “the ideology of philosophical liberalism” and its pitting of “freedom of thought” and a “model of protest” against the “authority of tradition,” remarks like the following are made:

The phenomenon of dissent can have diverse forms. Its remote and proximate causes are multiple…

The weight of public opinion when manipulated and its pressure to conform also have their influence. Often models of society promoted by the “mass media” tend to assume a normative value…

Dissent sometimes also appeals to a kind of sociological argumentation which holds that the opinion of a large number of Christians would be a direct and adequate expression of the “supernatural sense of the faith”...

[But] not all the ideas which circulate among the People of God are compatible with the faith. This is all the more so given that people can be swayed by a public opinion influenced by modern communications media.

End quote. Clearly, then, when Donum Veritatis expresses reservations about the mass media, what it has in view are the secular liberal values that dominate modern mass media and have reshaped public opinion by means of it, and the way that dissenting theologians have sought allies in the mass media in order to reshape Church teaching in a similar way. It is not the use of mass media per se that is bad. What is bad is trying to pressure the Church into conforming itself to the values that dominate modern mass media and public opinion.

Canon 212 of the Code of Canon Law gives further support to the legitimacy of public expressions of criticism. It states:

The Christian faithful are free to make known to the pastors of the Church their needs, especially spiritual ones, and their desires.

According to the knowledge, competence, and prestige which they possess, they have the right and even at times the duty to manifest to the sacred pastors their opinion on matters which pertain to the good of the Church and to make their opinion known to the rest of the Christian faithful, without prejudice to the integrity of faith and morals, with reverence toward their pastors, and attentive to common advantage and the dignity of persons.

End quote. This passage makes it clear that Catholics may make their opinions known not only “to the sacred pastors,” but also “to the rest of the Christian faithful.” It is also important to note, however, that the passage adds some important qualifications. For one thing, it tells us that the opinions expressed ought to reflect a sufficient level of “knowledge, competence, and prestige.” Neither Donum Veritatis nor canon law give a blank check to just any old yahoo with a Blogger account who wants to mouth off. Second, Catholics must express their opinions with sufficient “reverence toward their pastors.” More on this latter qualification presently.

The teaching of the tradition

The teaching of Donum Veritatis is not some modern novelty. It has precedents in St. Paul’s correction of St. Peter, in Pope Innocent III’s statement that he could legitimately be judged “on account of a sin committed against the faith,” and in the correction of Pope John XXII by the theologians of his day. It has also been given expression over the centuries by several saints and approved theologians.

St. Thomas Aquinas’s teaching on the subject in Summa Theologiae II-II.33.4 is worth quoting at length:

[F]raternal correction is a work of mercy. Therefore even prelates ought to be corrected...

A subject is not competent to administer to his prelate the correction which is an act of justice through the coercive nature of punishment: but the fraternal correction which is an act of charity is within the competency of everyone in respect of any person towards whom he is bound by charity, provided there be something in that person which requires correction…

Since, however, a virtuous act needs to be moderated by due circumstances, it follows that when a subject corrects his prelate, he ought to do so in a becoming manner, not with impudence and harshness, but with gentleness and respect…

It would seem that a subject touches his prelate inordinately when he upbraids him with insolence, as also when he speaks ill of him...

To withstand anyone in public exceeds the mode of fraternal correction, and so Paul would not have withstood Peter then, unless he were in some way his equal as regards the defense of the faith. But one who is not an equal can reprove privately and respectfully…

It must be observed, however, that if the faith were endangered, a subject ought to rebuke his prelate even publicly. Hence Paul, who was Peter's subject, rebuked him in public, on account of the imminent danger of scandal concerning faith, and, as the gloss of Augustine says on Galatians 2:11, “Peter gave an example to superiors, that if at any time they should happen to stray from the straight path, they should not disdain to be reproved by their subjects.”

To presume oneself to be simply better than one's prelate, would seem to savor of presumptuous pride; but there is no presumption in thinking oneself better in some respect, because, in this life, no man is without some fault. We must also remember that when a man reproves his prelate charitably, it does not follow that he thinks himself any better, but merely that he offers his help to one who, “being in the higher position among you, is therefore in greater danger,” as Augustine observes in his Rule quoted above.

End quote. Similarly, when discussing Paul’s rebuke of Peter in his Commentary on Galatians, Aquinas says that this rebuke was “just and useful” because of “the danger to the Gospel teaching,” and that “the manner of the rebuke was fitting, i.e., public and plain… because [Peter’s] dissimulation posed a danger to all.” Aquinas observes:

Therefore from the foregoing we have an example: to prelates, indeed, an example of humility, that they not disdain corrections from those who are lower and subject to them; to subjects, an example of zeal and freedom, that they fear not to correct their prelates, particularly if their crime is public and verges upon danger to the multitude.

End quote. Several aspects of Aquinas’s teaching here merit emphasis, because they correct a number misunderstandings that are common in Catholic circles. First, a Catholic can correct a prelate (i.e. someone with ecclesiastical authority, such as a bishop). Some Catholics falsely suppose otherwise, on the grounds that a subject has no authority over a prelate. But as Aquinas points out, what a subject lacks is authority to secure justiceby punishing a prelate for wrongdoing. Only a superior can do that. That does not entail that a subject cannot criticize a prelate, so long as the prelate really is guilty of wrongdoing, the criticism is respectful, and the subject is acting out of charity rather than pretending to exercise authority over the prelate. Aquinas even says that the scriptural account of Paul rebuking Peter was meant precisely as “an example of zeal and freedom” to Christians so that they would “fear not to correct their prelates.”

Second, the pope is among those who can be corrected in this way. This is obvious from the fact that Aquinas is speaking of prelates in general, and the pope is a prelate. Furthermore, the example of correction Aquinas cites is Paul’s correction of Peter, and Peter was a pope. The fact that the pope has no superior on Earth is irrelevant, because, again, what is in view here is not a subject punishing a pope so as to secure justice (which no subject of the pope may do), but rather merely respectfully criticizinga pope out of charity.

Third, Aquinas is clear that while such correction of a prelate should in the ordinary case take place privately, there are also cases where it can and should be done publicly. Specifically, Aquinas says that public rebuke of a prelate would be called for “if the faith were endangered” or if his “crime is public and verges upon danger to the multitude.”

Fourth, another reason such correction of a prelate can be called for is for the sake of the prelate himself. If a pope is guilty of serious error and of leading others into error, one does not show greater piety or loyalty to him by pretending otherwise. On the contrary, one contributes to endangering his soul. For precisely because of his greater responsibility, he is in “greater danger” spiritually, as Aquinas (following Augustine) puts it. One of the things a prelate is in greater danger of is arrogance, so that, as Aquinas says, correction from a subordinate can help a prelate to develop humility.

Fifth, Aquinas’s remarks show that it is silly to accuse those who criticize a prelate of necessarily thinking themselves “more Catholic than the pope.” For one thing, as Aquinas says, when a Catholic criticizes a prelate, “it does not follow that he thinks himself any better, but merely that he offers his help.” For another, a Catholic who criticizes a pope or other prelate might in fact be better in some respect. As Aquinas writes, “there is no presumption in thinking oneself better in some respect, because, in this life, no man is without some fault.” The theologians who criticized Pope John XXII for his theological errors were in fact better than him with respect to their understanding of the specific theological matter at issue. The Catholics of Pope Urban VI’s day who criticized him for his arrogance and foolish policies were in fact better than him with respect to their wisdom vis-à-vis policy. Catholics who condemn the immoral personal lives that a number of popes of the past have had are in fact better than those popes with respect to their personal moral virtue. And so on.

Sixth, it cannot be emphasized too strongly that, as Aquinas notes, criticism of a prelate must be carried out “with gentleness and respect” and not with “impudence” or “insolence.” Sometimes Catholics who raise legitimate criticisms of a pope publicly treat him with the sort of contempt and flippancy with which radio hosts and comedians typically treat politicians and other public figures in modern liberal democracies. This is gravely wrong. Even when your father is in error and must be rebuked, he is still your father and the Fourth Commandment is still in force. You may not belittle him or treat him as if he were some flunky. Now, the pope is a spiritual father, and more than that, he is the Vicar of Christ. His subjects must always act in a way consistent with the high dignity of his office, even when he is not living up to the demands of that office.

That does not mean that in evaluating the problematic words and actions of a pope, we must deny harsh truths. For example, it is not disrespectful or insolent to judge that Pope Honorius abetted heresy, or that Pope Stephen VI was insane, or that Pope Urban VI was foolish, or that Popes John XII and Benedict IX lived evil lives. These are simply straightforward factual judgments based on evidence. The point is that the legitimacy of criticism of a pope under certain circumstances has nothing whatsoever to do with the modern liberal individualist mentality of treating authority with contempt, celebrating the rebel and the dissident, etc. Indeed, legitimate criticism of a pope is essentially a matter of upholding his authority by helping him better to fulfill the purpose of his office, viz. passing on the deposit of faith and teaching it to his spiritual children. The aim is to urge him to be more pope-like, more father-like, not less.

The key is to keep in mind that the papacy has a teleologyor final cause. The pope is “not an absolute monarch” and “must not proclaim his own ideas” (to quote Benedict XVI again), but rather must “religiously guard and faithfully expound the… deposit of faith” (as Vatican I put it), “teaching only what has been handed on… guarding it scrupulously and explaining it faithfully” (as Vatican II says). To the extent that a pope fails to do this, he is like a father who misleads his children. Now, just as it would be perverse to defend an abusive father’s actions in the name of fatherhood, so too would it be perverse to defend an errant pope’s actions in the name of papal authority. As the eminent 16thcentury Dominican theologian Melchior Cano put it:

Peter has no need of our lies or flattery. Those who blindly and indiscriminately defend every decision of the Supreme Pontiff are the very ones who do most to undermine the authority of the Holy See – they destroy instead of strengthening its foundations. (Quoted in George Weigel, Witness to Hope, p. 15)

At the same time, just as it would also be perverse to pretend that one is upholding fatherhood by mocking and abusing an errant father, so too would it be perverse to pretend to be upholding papal authority by criticizing a pope in a disrespectful manner. The teleology of fatherhood shows both that a father can be criticized under certain circumstances, but also how such criticism must be conducted. Something similar is true of the papacy. Its final cause is to function as a doctrinal authority. To acquiesce in papal error would undermine the “doctrinal” part of this function, but to reprove error in an impudent manner would undermine the “authority” part of the function.

As the quote from Cano indicates, Aquinas is by no means the only thinker in the tradition to recognize that there can be cases when a pope should not be followed. Cardinal John Henry Newman speculated about the possibility of “extreme cases in which Conscience may come into collision with the word of a Pope, and is to be followed in spite of that word” though he judged such cases to be “very rare” (Newman and Gladstone: The Vatican Decrees, pp. 127 and 136). In support, Newman cites remarks from St. Robert Bellarmine and Cardinal John de Torquemada. Cardinal Torquemada wrote:

Although it clearly follows from the circumstance that the Pope can err at times, and command things which must not be done, that we are not to be simply obedient to him in all things, that does not show that he must not be obeyed by all when his commands are good. To know in what cases he is to be obeyed and in what not... it is said in the Acts of the Apostles, ‘One ought to obey God rather than man;’ therefore, were the Pope to command anything against Holy Scripture, or the articles of faith, or the truth of the Sacraments, or the commands of the natural or divine law, he ought not to be obeyed, but in such commands to be passed over. (Newman and Gladstone, p. 124)

And Bellarmine taught:

[A]s it is lawful to resist the Pope, if he assaulted a man’s person, so it is lawful to resist him, if he assaulted souls, or troubled the state, and much more if he strove to destroy the Church. It is lawful, I say, to resist him, by not doing what he commands, and hindering the execution of his will. (Newman and Gladstone, p. 125)

We find similar remarks from other eminent theologians and churchmen of the past. For example, Cardinal Cajetan held that in dealing with a pope who abuses his office, Catholics can legitimately “oppose the abuse of power which destroys by suitable remedies such as not obeying, not being servile in the face of evil actions, not keeping silence, [and] by arguing” (quoted in Miller, The Shepherd and the Rock, p. 295). Similarly, Cardinal Raphael Merry del Val wrote:

Great as our filial duty of reverence is towards what ever [the pope] may say, great as our duty of obedience must be to the guidance of the Chief Shepherd, we do not hold that every word of his is infallible, or that he must always be right…

[E]ven to-day a Bishop might… expostulate with a Pope, who, in his judgment, might be acting in a way which was liable to mislead those under his own charge, and then write to his critics that he had not hesitated to pass strictures upon the action of the successor of S. Peter… The hypothesis is quite conceivable, and in no way destroys or diminishes the supremacy of the Pope. And yet an individual Bishop does not occupy the exceptional position of S. Paul, a fellow-Apostle of the Prince of the Apostles. Even a humble nun, S. Catherine of Siena, expostulated with the reigning Pontiff, in her day, whilst full acknowledging all his great prerogatives. (The Truth of Papal Claims, pp. 19 and 74)

The case of Pope Francis

I hardly need point out that these considerations have contemporary relevance. Pope Francis has made statements that at least appear to conflict with traditional Catholic teaching on Holy Communion for divorced and remarried Catholics and non-Catholics, contraception, capital punishment, the criteria for the validity of a marriage, and other topics. He has also studiously refused to respond even to polite requests for clarification and reaffirmation of traditional teaching on these subjects.

For these statements he has been respectfully criticized by many prominent Catholic churchmen, philosophers, and theologians with longstanding reputations for fidelity to the Magisterium, including Cardinal Raymond Burke, Cardinal Carlo Caffarra, Cardinal Walter Brandmüller, Cardinal Joachim Meisner, Cardinal Willem Eijk, Cardinal Janis Pujats, Bishop Tomash Peta, Bishop Carlo Maria Vigano, Bishop Luigi Negri, Bishop Jan Pawel Lenga, Bishop Athanasius Schneider, Bishop Józef Wróbel, Bishop Jan Watroba, Bishop Thomas Tobin, Bishop René Henry Gracida, Fr. Aidan Nichols, Fr. Thomas Weinandy, Msgr. Nicola Bux, Fr. Gerald Murray, Robert Spaemann, Josef Seifert, Germain Grisez, John Finnis, Edward Peters, E. Christian Brugger, Christopher Tollefsen, Joseph Shaw, and John Rist. The list could easily be expanded. There have also been petitions such as the statement of the 45 theologians, the “filial correction” issued by 62 theologians and priests, the pastoral appeal from priests to their bishops to address the current crisis, and, of course, the dubia issued by four of the cardinals mentioned above. The pope’s own former head of the CDF, Cardinal Gerhard Müller, has also been critical of an absence of theological rigor under Francis’s pontificate, the pope’s manner of dealing with subordinates, and a general climate of “fear” he says exists in the Curia.

For so many prominent faithful Catholics publicly to criticize a pope seems unprecedented, though perhaps the criticism Pope John XXII faced from the theologians of his day was somewhat similar. However, for a pope to make so many problematic statements while persistently ignoring repeated respectful requests for clarification is certainlyunprecedented. Hence the criticism is not surprising. More to the present point, it is manifest from Donum Veritatis, canon law, and the teaching of St. Thomas Aquinas and other approved theologians that the criticism is clearly within the bounds of what the Church permits. Those who accuse these critics of being “dissenters” or disloyal to the Holy Father are either being intellectually dishonest or simply don’t know what they are talking about.

Moreover, the legitimacy of this criticism is clear even from the teaching of Pope Francis himself. For one thing, the pope has explicitly said that some of his public remarks are open to legitimate criticism. For another, in his recent exhortation Gaudete et Exsultate, Pope Francis asserts that “doctrine, or better, our understanding and expression of it, is not a closed system, devoid of the dynamic capacity to pose questions, doubts, inquiries.” Now, in my opinion this statement needs serious qualification. But if Pope Francis believes that a Catholic can legitimately “pose questions, doubts, inquiries” about doctrines that have for millennia been consistently taught by scripture, the Fathers and Doctors of the Church, and all previous popes, then he cannot consistently deny that it can be legitimate to “pose questions, doubts, inquiries” about statements of his own that seem inconsistent with those doctrines.

Related posts:

Papal fallibility

Denial flows into the Tiber

How Pope Benedict XVI dealt with disagreement

Nudge nudge, wink wink

Published on May 20, 2018 11:17

May 17, 2018

Aquinas on the human soul

My article “Aquinas on the Human Soul” appears in the anthology

The Blackwell Companion to Substance Dualism

, edited by Jonathan Loose, Angus Menuge, and J. P. Moreland and just published by Wiley-Blackwell. Lots of interesting stuff in this volume. The table of contents and other information are available here.

My article “Aquinas on the Human Soul” appears in the anthology

The Blackwell Companion to Substance Dualism