Edward Feser's Blog, page 62

October 26, 2017

Around the web with Five Proofs

At The Secular Outpost, atheist Bradley Bowen inaugurates what promises to be an interesting series of posts on

Five Proofs of the Existence of God

. His verdict so far:

At The Secular Outpost, atheist Bradley Bowen inaugurates what promises to be an interesting series of posts on

Five Proofs of the Existence of God

. His verdict so far: Unlike the cases for God by Geisler and Kreeft, Feser’s case is NOT a Steaming Pile of Crap, and it is a great pleasure to consider a case that at least has the potential to be a reasonable and intelligent case for God.

End quote. As they say, read the whole thing. “Feser’s case is NOT a Steaming Pile of Crap” may be my favorite book review ever.

At the blog After Aristotle, philosopher Richard Hennessey comments on Five Proofs, which he says “commands serious reading.”

And at Pagan Bloggers, Steven Dillon comments on the book from a polytheist perspective. He’s disappointed that I didn’t say more about that subject. I would have thought that giving arguments for the unity of God (which I do at some length in the book) counts as addressing that topic. But see for yourself.

Published on October 26, 2017 18:02

October 24, 2017

Five Proofs on The Patrick Coffin Show

A few weeks ago, I was interviewed by Patrick Coffin before a live audience for a special episode of his show. The subjects were my book

Five Proofs of the Existence of God

, atheism, and related matters. You can now watch Part I of the episode at Patrick’s website or at YouTube. Part II is a Q and A session that will be posted next week.Other recent interviews include those on

The Ben Shapiro Show

,

The Andrew Klavan Show

,

The Dennis Prager Show

,

The Michael Medved Show

, and many others. Further media appearances forthcoming. Stay tuned.

A few weeks ago, I was interviewed by Patrick Coffin before a live audience for a special episode of his show. The subjects were my book

Five Proofs of the Existence of God

, atheism, and related matters. You can now watch Part I of the episode at Patrick’s website or at YouTube. Part II is a Q and A session that will be posted next week.Other recent interviews include those on

The Ben Shapiro Show

,

The Andrew Klavan Show

,

The Dennis Prager Show

,

The Michael Medved Show

, and many others. Further media appearances forthcoming. Stay tuned.

Published on October 24, 2017 17:24

October 21, 2017

Reply to Ivereigh, Brugger, Shea, and Fastiggi

My recent Catholic Herald articleabout Pope Francis and capital punishment has gotten a fair bit of attention. Some of it has been positive, some of it less so. In a new essay at Catholic World Report, I respond to four critics – Austen Ivereigh, E. Christian Brugger, Mark Shea, and Robert Fastiggi.Meanwhile, Fr. Dwight Longenecker, commenting on the current controversy and on

By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed: A Catholic Defense of Capital Punishment

, writes:

My recent Catholic Herald articleabout Pope Francis and capital punishment has gotten a fair bit of attention. Some of it has been positive, some of it less so. In a new essay at Catholic World Report, I respond to four critics – Austen Ivereigh, E. Christian Brugger, Mark Shea, and Robert Fastiggi.Meanwhile, Fr. Dwight Longenecker, commenting on the current controversy and on

By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed: A Catholic Defense of Capital Punishment

, writes:As we are getting accustomed to, the pope’s comments lack precision and his increasingly Anglican-style ambiguity allows for varying interpretations.

However, the debate on capital punishment is a good one to have and there are strong arguments to be made on both sides…

But instead of a vigorous debate or dialogue progressives seem intent on shutting down the discussion… Although I am not a death penalty advocate, I reviewed Feser and Bessette’s book in a balanced way for a centrist Catholic website, but as far as I know the review has not been published. Is dialogue on this issue to be desired or shall we all duck for cover as the “Roma locuta” flags are being waved and we are expected to march in lock step?...

Whether we like it or not, Bessette and Feser have made strong points, but their arguments are not being addressed with any seriousness or sound reasoning. There are plenty of people who can answer Bessette and Feser, and they should do so.

End quote. Concerns about the pope’s recent remarks have also been raised by theologian Eduardo Echeverria at Catholic World Report, by P. J. Smith at First Things, by philosopher Joseph Shaw at Rorate Caeli, and by theologian Fr. Brian Harrison at One Peter Five. LifeSiteNews interviews five Catholic scholars who find the pope’s remarks problematic.

Published on October 21, 2017 17:58

October 15, 2017

Pope Francis on capital punishment

Pope Francis has made news with his recent remarks about capital punishment and the catechism. They are seriously problematic. In an article at Catholic Herald, I provide an analysis.

Pope Francis has made news with his recent remarks about capital punishment and the catechism. They are seriously problematic. In an article at Catholic Herald, I provide an analysis. LifeSiteNews has also asked me to comment on the story.

In our book By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed: A Catholic Defense of Capital Punishment (at pp. 183-96), Joseph Bessette and I analyze in detail Pope Francis’s previous statements on this subject. They too are problematic, but less so than the pope’s most recent remarks.

Published on October 15, 2017 11:58

Five Proofs with Prager et al. (UPDATED)

UPDATE 10/17: You can now hear the Prager show interview online.

UPDATE 10/17: You can now hear the Prager show interview online. This Tuesday, Oct. 17, at 11 am PT, I will appear on The Dennis Prager Show to discuss my book Five Proofs of the Existence of God .

In early November, I will appear on Unbelievable? with Justin Brierley to discuss the book.More media appearances forthcoming. Stay tuned. In the meantime, you can listen to my recent appearances on A Closer Look with Sheila Liaugminas (the interview begins about 14 minutes into the show), Janet Mefferd Today , and Morning Air with John Harper (the interview begins about 41 minutes into the show). Earlier radio appearances can be found here.

Published on October 15, 2017 11:27

Five Proofs with Prager et al.

This Tuesday, Oct. 17, at 11 am PT, I will appear on

The Dennis Prager Show

to discuss my book

Five Proofs of the Existence of God

.

This Tuesday, Oct. 17, at 11 am PT, I will appear on

The Dennis Prager Show

to discuss my book

Five Proofs of the Existence of God

. In early November, I will appear on Unbelievable? with Justin Brierley to discuss the book.More media appearances forthcoming. Stay tuned. In the meantime, you can listen to my recent appearances on A Closer Look with Sheila Liaugminas (the interview begins about 14 minutes into the show), Janet Mefferd Today , and Morning Air with John Harper (the interview begins about 41 minutes into the show). Earlier radio appearances can be found here.

Published on October 15, 2017 11:27

October 10, 2017

Liberty, equality, fraternity?

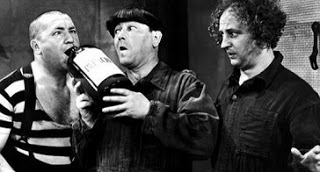

Pictured above are the ideals of the French Revolution, and of the modern world in general – liberty, equality, and fraternity. Note carefully how they manifest their chief attributes. Liberty freely indulges its desires. Equality shares what it has. Fraternity looks on with brotherly concern. And they’re all idiots.“Surely you’re not against liberty, equality, and fraternity?!” you ask. Well, no, not necessarily – depending on what you mean by those terms. The trouble is that though some of the ideas that commonly go under those labels are good, others are very bad. But the good and bad frequently get mixed together, so that it is assumed that if you accept liberty, equality, or fraternity in one sense, you have to accept them in the other senses as well.

Pictured above are the ideals of the French Revolution, and of the modern world in general – liberty, equality, and fraternity. Note carefully how they manifest their chief attributes. Liberty freely indulges its desires. Equality shares what it has. Fraternity looks on with brotherly concern. And they’re all idiots.“Surely you’re not against liberty, equality, and fraternity?!” you ask. Well, no, not necessarily – depending on what you mean by those terms. The trouble is that though some of the ideas that commonly go under those labels are good, others are very bad. But the good and bad frequently get mixed together, so that it is assumed that if you accept liberty, equality, or fraternity in one sense, you have to accept them in the other senses as well.How to untangle the mess? And what exactly are the good and bad senses to which I refer? The best place to start is with how the greatest of the classical and medieval thinkers understood social life. This is the natural law view of the world, which is of course the correct view of the world (or so I would say, being a traditional natural law theorist myself). The natural law position is harder to convey through labels as rhetorically powerful as “Liberté, égalité, fraternité!” But then, what makes those terms rhetoricallyeffective – they are simplistic and ambiguous – is precisely the source of their philosophical inadequacy.

If you must have three words or phrases that sum up the natural law position, they would, I suppose, be: subsidiarity; solidarity; and family and patriotism. Liberty, equality, and fraternity as usually understood are distortions of these three. There are other and opposite distortions as well. For example, tribalism and nationalism are other, very different distortions of family and patriotism. The best way to understand the distortions is to understand what they are distortions of, so let’s walk through them. It is best to go in reverse order.

Family and patriotism

Man is by nature a social animal. A new human being is for many years dependent on his parents and siblings both for his material well-being and for his basic understanding of what the world is like and how to behave within it. When he becomes an adult, he finds himself drawn before long to bond with another human being, resulting in offspring of his own for whom he must provide materially and spiritually. When he is old, he becomes dependent once again, this time on those offspring. Every human being, no matter how independent in other respects, to some extent and for a considerable portion of his life finds himself dependent on and/or responsible for other family members in one or more of these ways.

The family is thus the fundamental context within which we manifest our social nature. We form friendships too, of course, but these are like extensions of family relations. Hence we say that a close friend is like a brother to one, that a trusted mentor is like a father to one, that a mentee is like a son to one, and so forth. Even less close friendships are analogous to family relationships insofar as they only form where we have at least some small degree of intimacy with another and at least some small degree of affection. Hence a friendly workplace is often described as feeling “like a family.” It is family relationships that tend to form the model for most other relationships that are important to us, even if the analogy is sometimes very loose.

There are also, of course, some relationships that are too remote and impersonal plausibly to be modeled on family relationships. For example, the stranger in the street to whom you give directions, the vendor from whom you regularly buy your newspaper, the mailman, etc. are not plausibly thought of as “brothers” in the way that a friend or even co-worker might be. But these sorts of relationships are not the fundamental way in which we manifest our social nature. They come into existence only after we have been socialized by growing up in a certain family situation. Moreover, even these relationships are defined by reference to family relationships in an indirect way. We think of the people in question as strangers precisely insofar as they are noteither family members or the sort of honorary family members that friends are.

Nuclear families naturally give rise to extended families, and historically these in turn gave rise to tribes and nations. The allegiance we naturally feel for our families naturally gets extended to these larger social formations which grew out of the family. Patriotism is essentially family loyalty writ large. And the offense people take at attitudes or actions perceived as unpatriotic is to be understood as analogous to the offense we feel when a family member exhibits disloyalty to the family or brings disgrace to it. Patriotism is thus natural and good, just as family loyalty is natural and good. It is as necessary to the health of a nation as family loyalty is to the health of a family, and thus the absence of it is dysfunctional in something like the way a family is dysfunctional when its members feel no affection or loyalty for it.

Notice that there is nothing whatsoever in patriotism so understood that entails hostility or contempt for other nations, any more than the special love one has for one’s own family entails hostility or contempt for other families. Nor does patriotism entail even a mere lack of concern for other nations. On the contrary, since the human race is essentially a very large extended family, human beings are naturally bound to exhibit some degree of fellow feeling and concern for all other human beings. However, this is also quite naturally never likely to be as strong as the special concern one has for one’s own nation, just as one’s allegiance toward and concern for one’s own nation is never going to be as strong as the concern and allegiance one has for one’s own immediate family.

Human beings thus naturally relate to others in a way that is usefully illustrated by way of concentric circles. Our immediate allegiances and responsibilities concern members of our own nuclear families and friends. In the next concentric circle would be members of our extended families, toward whom we also owe a certain degree of allegiance and responsibility, but where the debt is not as great as that owed to our own immediate family. In the next circle beyond that are our countrymen, to whom we owe allegiance and toward whom we bear some responsibility, but where these are not as great as the allegiance and responsibility we owe to our extended families, let alone our immediate families. In the outermost circle are those of other nations and the human race in general, to whom we also owe real allegiance and to whom we have real responsibilities, but where these are not as great as what we owe to our own nations, much less to our extended and immediate families.

It is virtuous, then, to have a special loyalty toward one’s family and to be a patriot, and to lack these habits of thought and action is, accordingly, vicious. But as with other virtues, there are in fact two corresponding vices here, one of excess and one of deficiency. The vice of excess is manifested in tribalismand nationalism. Consider, for example, the Mafioso whose allegiance to his clan is so excessive that he thinks crimes and other immoralities justifiable when they are done in the interests of his family. Or think of the person who so deeply identifies himself with the ethnic group to which he belongs that he is hostile to and paranoid about those outside that group. Or think of the nationalist who believes that his country or race ought to impose its will on other countries and races, and exploit them for its own benefit.

The vice of deficiency is where fraternity comes in. Just as one can be excessively attached to one’s own family or nation, so too can one be insufficientlyattached to them. This vice is exhibited by those who think it best to regard oneself as a “citizen of the world” or member of the “global community” rather thanhaving any special allegiance to one’s own country. It is the idea of a “world without borders” and a “brotherhood of man” – hence fraternityconstrued as an ideal of universal brotherhood to replace family loyalty, patriotism, and other local allegiances.

To be sure, there is a sense in which all human beings are brethren; as I said above, we are all members of the human race and thus in that sense all members of the same maximally extended family. The problem comes when the idea of brotherhood is falsely taken to imply that there is something suspect about national or other group loyalties – when it is taken to imply that one’s countrymen are one’s brothers in no stronger sense than any other human being is.

Family relationships are so close and deep that it is difficult for this vice to eat away at family loyalties the way it often eats away at patriotism. But even here the vice has an impact. Think of the way that movies and other pop culture artifacts portray the biological, nuclear family as inevitably dysfunctional, and commend instead novel “family” arrangements of individuals’ own design – “families of choice” or “found families,” as they are sometimes called.

The opposite extreme vices I’ve been describing tend to play off of one another. Hence, tribalism and nationalism sometimes arise as an overreaction against the bloodless cosmopolitanism of the “global community” idea, with its tendency to collapse into an alienating individualism. Meanwhile, the “global community” ideal sells itself as the only alternative to nationalism and tribalism, and its proponents tend to see these vices in every expression of patriotism. Each extreme tends to blind its adherents to the sober middle ground.

Solidarity

The natural law understanding of society is an organicone, in that it takes the members of any society to be related to one another in something loosely analogous to the way that the organs of a living thing are related to one another. Just as each organ serves a distinct and essential role in realizing the good of the whole organism, so too does each member of a society serve a distinct and essential role in realizing the good of that society. And just as an organism takes care to nourish and protect each of its parts, so too ought society to be organized in such a way that each of its members can flourish (subject to the qualifications entailed by the principle of subsidiarity, to be discussed below). The parts of the body are in solidarity with one another, and so too must each part of society be.

Pope Pius XI gave a classic expression of this organic model as applied to the family in his encyclical Casti Connubii . He speaks of “this body which is the family,” in which “the man is the head, the woman is the heart, and as he occupies the chief place in ruling, so she may and ought to claim for herself the chief place in love.” Naturally, this is politically incorrect these days, but anyone who sees in it a recipe for patriarchal tyranny is not paying attention to the force of the analogy (not to mention “the chiefplace in love” Pius assigns to mothers). In a literal body, the head functions for the sake of the heart and the other parts just as the other parts function for the sake of it. Or rather, they all function for the sake of the whole, and the whole looks after each part. And that is the way the family is understood. Political authority, on the natural law conception, was originally an extension of paternal authority, with the earliest rulers being patriarchs or fathers of tribes and nations, analogous to the fathers who governed nuclear families. As nations got larger and the relationships between citizens less personal, heads of countries naturally came to seem “father”-like in only the loosest way, and the consent of and input from the governed came to play an increasingly prominent role in governance. This is perfectly appropriate given subsidiarity (again, to be discussed below). But the essentially organic nature of society, and the need for each part to be in solidarity with the others, does not change.

Solidarity is incompatible with the notion of class struggle. In an organism, the fact that head, heart, arms, legs, eyes, ears, etc. have very different roles and needs does not mean they are in competition or at odds with one another. On the contrary, they need and complement one another. Similarly, capitalists and managers on the one hand and workers on the other, political authorities and those they govern, men and women, people of different ethnic groups, and so forth, are not in the nature of things at odds and cross purposes, but also complement one another and bring different strengths to the table. The health of society requires, not the victory of one class or group over another or the elimination of class and group distinctions altogether, but rather the sober recognition of their differences and mutual respect and cooperation between them.

Solidarity is also incompatible with the notion of racialstruggle, which is essentially a reflection of nationalism, the perversion of patriotism. For one thing, though the solidarity we owe the human race in general is not as strong as the solidarity we owe our own family or country, we do owe it. Every human being is a brother in an extended sense, and thus it is wrong to regard any other racial or ethnic group with hostility or contempt. For another thing, very large nations are united not only by blood but by ties of shared history, language, culture, and so forth. Even in the absence of blood ties, there is something analogous to an adoptive family connection between citizens. One’s countrymen of any race or ethnicity are thus owed the same allegiance.

Now, this organic conception of society has two key components: the notion of society as a whole that is analogous to the body of an organism; and the notion of the members of society as analogous to distinctive parts of this whole, corresponding to the distinctive parts of the body (eyes, ears, heart, legs, etc.). Distortions of the ideal of solidarity tend to distort one or other of these key components.

Hence, totalitarianism in its various forms (such as the class-oriented totalitarianism of communism or the race-oriented totalitarianism of Nazism) puts so much emphasis on the whole of which the members of society are parts that the parts essentially disappear. The members are no longer seen as unique, each having needs and dignity of their own that the whole body must respect (the way that its eyes, arms, heart, lungs, etc. are cherished and looked after by an organism). Rather, the members come to be seen as fleeting, interchangeable, and easily replaceable, like mere cells are, or even altogether dispensable, like waste products or hair and fingernail clippings. The disanalogies between individual human beings and parts of the body – and no natural law theorist would deny that there are disanalogies, since the analogy is not exact – come to be ignored. It is in part to remedy this dangerous misapplication of the organic analogy that the natural law theorist insists on balancing the principle of solidarity with the principle of subsidiarity.

There is another way solidarity can be distorted, which brings us to equality. There is a clear sense in which the parts of the body, and the members of society too, are of equal concern. As St. Paul writes:

The eye cannot say to the hand, “I have no need of you,” nor again the head to the feet, “I have no need of you.” On the contrary, the members of the body that seem to be weaker are indispensable, and those members of the body that we think less honorable we clothe with greater honor, and our less respectable members are treated with greater respect; whereas our more respectable members do not need this. But God has so arranged the body, giving the greater honor to the inferior member, that there may be no dissension within the body, but the members may have the same care for one another. If one member suffers, all suffer together with it; if one member is honored, all rejoice together with it. (I Corinthians 12:21-26)

But equal concern for all does not entail concern that all be made equal. For all are not equal in every significant respect, and it is for the good of the whole that they are not. The eyes and the legs are not equally good at seeing or equally good at walking. Each has its job, and each has to do its job if the whole organism is to flourish. An organism that does not take care of both its eyes and its legs is going to be dysfunctional. But an organism that thinks that this means trying to force the eyes to walk and trying to force the legs to see is also going to be dysfunctional.

Modern egalitarianism makes essentially this mistake. In the name of equal concern for all, it resists or even rejects the idea that different members of society have different roles, aptitudes, and needs. Hence socialism’s hostility to the very existence of different classes. Hence feminism’s hostility to traditional sex roles within the family and to the idea that men and women naturally tend to differ in psychological traits no less than they do physiologically. Hence the liberal’s dogmatic insistence on seeing persistent differences in economic and other outcomes as a result of unjust discrimination and insufficiently vigorous social engineering. Hence the Rawlsian attitude of regarding individuals’ differing natural assets as “arbitrary from a moral point of view” so that the redistribution of the fruits of those varying assets is called for. Hence the egalitarian’s constant, shameless blurring of the distinction between helping the poor (which solidarity most definitely requires) and equalizing economic outcomes (which solidarity most definitely does not require). Hence Marx’s ridiculous fantasy in The German Ideology of:

communist society, where nobody has one exclusive sphere of activity but each can become accomplished in any branch he wishes, [where] society regulates the general production and thus makes it possible for me to do one thing today and another tomorrow, to hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticise after dinner, just as I have a mind, without ever becoming hunter, fisherman, herdsman or critic.

Rightly understood, solidarity not only does not entail radical egalitarianism, it positively excludes it. For egalitarianism, no less than radical individualism, is contrary to the organic nature of society. The radical individualist denies that we are in any sense parts of a larger social body. The radical egalitarian does not necessarily deny this, but does deny that we are different parts. He wants to make us all eyes, or all legs, or all hearts.

This is why popes like Leo XIII and Pius XI were extremely hard on socialism and egalitarianism even as they called on capitalist society to reform itself so as to improve the conditions of workers and the poor. This was not inconsistency on their part, but on the contrary perfect consistency, given the organic natural law conception of society with which they were working. The teaching of the popes, like the teaching of natural law, is both that man is a social animal, and that he is not a socialist animal.

Subsidiarity

An organism cannot fully flourish if it is interfered with – if you cage it, put it in fetters, constantly poke and prod it, or even just make yourself a nuisance, as a horsefly does. It needs room to breathe, freedom of action, and the opportunity to make use of its special talents and knowledge.

Social organisms are like this too. A family has a concern for its members that is stronger than that of which outsiders are capable, and a knowledge of their needs that is greater and more intimate than that of outsiders. The family ought therefore to be left to run its own affairs as far as possible, with outside agencies either assisting or interfering only when the family simply cannot otherwise continue to function properly. Even then, when such intervention is necessary, it ought as far as possible to be those closest to the family itself – the extended family first and foremost, then local public authorities when absolutely necessary, and so on through the concentric circles mentioned earlier – who provide the assistance in question.

What goes for the family goes for other social organizations. The presumption is that they are to be left alone by higher-level social organizations, and that presumption can be overridden only when intervention is necessary to restore the proper function of the lower-level organizations, and only to the extent and for the time that this is necessary. This is the natural law principle of subsidiarity, given classic expression by Pope Pius XI in Quadragesimo Anno :

As history abundantly proves, it is true that on account of changed conditions many things which were done by small associations in former times cannot be done now save by large associations. Still, that most weighty principle, which cannot be set aside or changed, remains fixed and unshaken in social philosophy: Just as it is gravely wrong to take from individuals what they can accomplish by their own initiative and industry and give it to the community, so also it is an injustice and at the same time a grave evil and disturbance of right order to assign to a greater and higher association what lesser and subordinate organizations can do. For every social activity ought of its very nature to furnish help to the members of the body social, and never destroy and absorb them.

End quote. Like the organic conception of society enshrined in the principle of solidarity, the principle of subsidiarity is at odds with socialism and any other political program that would in the name of “social justice” usurp what private enterprise, local communities, churches, and in general what Edmund Burke famously called the “little platoons” of society can accomplish.

It is important to emphasize that this is a moralprinciple, and not merely a pragmatic one. The claim isn’t merely that a central government may opt not to meddle in the affairs of smaller scale institutions if it judges that this may be more efficient. It is that it must not meddle unless it is strictly necessary to do so. Hence, suppose it is possible to provide adequate health care for all in a private system supplemented by government assistance programs for the needy who are unable to acquire adequate care in the free market. (Whether this is in fact the case is not a debate I’m getting into here – it’s just an illustration.) Then, in that case, we are not merely in a situation where it is unnecessaryfor the state to socialize the medical system. According to the principle of subsidiarity, we are in a situation where the state morally must not do so – on pain of what Pius XI calls “injustice,” “grave evil,” and “disturbance of right order.”

Hence, socialism cannot be justified in the name of social justice, because social justice rightly understood is a matter of solidarity rather than egalitarianism, and because solidarity goes hand in hand with subsidiarity. Both principles are equally essential to the proper functioning of social institutions. Thus did Pius XI teach in the same encyclical that “no one can be at the same time a good Catholic and a true socialist.”

As Pius’s characterization of subsidiarity indicates, the principle applies even at the level of the individual. Again, he writes that “it is gravely wrong to take from individuals what they can accomplish by their own initiative and industry and give it to the community.” However, the reason why this is wrong is the same as the reason it is wrong unnecessarily to interfere with the family and other “little platoons.” Each of these smaller scale institutions within society has a special function of its own – just as, in an organism’s body, the eyes do the seeing, the legs do the walking, and so forth – and needs the freedom to get on with performing it. But so too does the individual. In particular, he needs the freedom to pursue the good as defined by natural law. And while the many differences between individual talents, interests, and circumstances entail a large degree of freedom on the part of individuals to work out what is personally best for them, the natural law entails certain absolute moral boundaries within which this freedom can be exercised.

In short, the freedom of individuals and of families and other social formations has a teleological foundation. It is fundamentally the freedom to do what is necessary or fitting for us to realize the ends toward which we are directed by nature. (I have spelled out the teleological foundation of natural rights in several places, such as my article “Classical Natural Law Theory, Property Rights, and Taxation,” which is reprinted in Neo-Scholastic Essays .)

This brings us at last to liberty. Understood as the freedom of individuals, families, churches and other “little platoons” to pursue the ends toward which the natural law directs them, liberty is essentially the same thing as subsidiarity, and under contemporary circumstances may be the most neglected and urgent of the requirements of social order emphasized by the natural law social theorist.

However, that is not how most people understand liberty today. Liberals, socialists, libertarians, and even many self-described conservatives think of “liberty” as essentially freedom from constraints on doing whatever one happens to want to do, rather than freedom to pursue what is in fact objectively good. They disagree about exactly what respect for liberty thus understood entails, but they all tend to divorce it from anything like an objective natural law teleological foundation. Justice Anthony Kennedy summed up this conception in a famous line from the Planned Parenthood v. Casey decision: “At the heart of liberty is the right to define one's own concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life.”

“Liberty” understood in this sense is the greatest threat to social order as natural law theory understands it. This is nowhere more obvious than in the case of the “liberty” ushered in by the sexual revolution and the enormous damage it has done to the institution of the family – that is to say, to the fundamental social institution.

In what natural law theory regards as a rightly ordered society, most people marry, and marriage typically results in children, and lots of them. This in turn creates a large social network of people known personally to one – lots of brothers and sisters, cousins, aunts and uncles, and so on – on whom individuals can fall back in times of need. Divorce is stigmatized, so that children generally have stable homes and discipline, and they and their mothers generally have a reliable provider. Elder family members are looked after by the new generation, just as they looked after that generation when it was in its infancy. Elder members also find ongoing purpose in helping to raise their grandchildren. In general, the good of the family takes precedence over the desires of the individual member. And this subordination of self-interest to the common good of the family makes people more sober and realistic in their expectations, less selfish, and better able to achieve a contentment that is deep and lasting even if not as titillating as running off to begin a second or third marriage.

Contrast that with the contemporary mentality, which regards sex and romance as primarily a matter of self-fulfillment, rather than having self-sacrifice for the sake of children and family as its natural end. Whereas the traditional arrangements commended by natural law subordinated the short-term interests of the individual to the long-term health of the family, the modern mentality subordinates the long-term health of the family to the short-term interests of the individual. Naturally, solidarity is weakened.

How so? First and most dramatically, enormous numbers of the inconvenient offspring that result from sexual relationships are now not only not looked after, but aborted – that is to say, to speak plainly, they are murdered by their own parents. Solidarity doesn’t get any weaker than that.

But even that is just the beginning. The children that people do have typically find themselves in very small families, with one or two other siblings at most. Divorce, remarriage, and the ensuing shuffling around of offspring and geographical separation often also make the relationships that exist between siblings (or half-siblings) more distant. Widespread fornication and divorce leave many women without providers and their children without a male role model. With only one or two children to look after them, elderly family members come to be seen as a greater burden. All of this results in greater poverty and in turn greater dependence on the state, as well as the anti-social behaviors (gang activity, crime, and the like) that young men are more prone to fall into in the absence of paternal discipline. Men, meanwhile, since they can easily find short-term sexual gratification outside marriage, become more boorish and selfish, more prone to use women and abandon them. Widespread pornography use makes them less able to find satisfaction with a real woman when they do marry, and contributes to marital discord and higher divorce rates. A great many women, tossed aside when “serially monogamous” men decide to marry someone else, are unable to find husbands at all, and after middle age face decades of loneliness and childlessness. Elderly family members are shuffled off to nursing homes and children to day care centers, to be looked after by paid employees rather than by other family members.

So, there are fewer nuclear families, the ones that do exist are much smaller and less stable, care for children and elderly is often largely impersonal and divorced from the family itself, and the extended family has largely disappeared as a background part of everyday life. People are more self-centered, less willing to sacrifice for the good even of their own flesh and blood. They are also lonelier, and more in need of, and demanding of, governmental assistance. In short, modern “liberty” undermines solidarity, which promotes state dependence, which undermines subsidiarity or liberty in the authentic sense.

It also destroys allegiance to larger social orders. If even the family itself is something to be broken apart and reinvented at personal whim, or even abandoned altogether, rather than sacrificed for, it is hardly surprising if one comes to see one’s country as having no special claim on one’s loyalty.

True social justice

Here is an irony of Orwellian proportions. The currency of the term “social justice” originated in Thomistic natural law social theory. It is often attributed to the great Jesuit natural law theorist Luigi Taparelli. It has to do with the just or right ordering of society as defined by strong families and cooperation between husband and wife in carrying out their respective roles for the sake of children and elders, solidarity and cooperation between economic classes and other social groups, and scrupulous attention to subsidiarity in the state’s relationship to the “little platoons” of society.

What today goes under the label of social justice – what self-described “social justice warriors” agitate for – is precisely the opposite of all of this. It entails sexual libertinism and abortion on demand, the feminist demonization of “patriarchy” and of traditional family roles, the incessant stirring up of tensions between economic classes and racial groups (e.g. the daily Two Minutes Hate directed at “one percenters,” “white privilege,” etc.), the relentless smearing of one’s country and its history, socialized medicine and socialized education, and so on. This might be liberty, equality, and fraternity after a fashion, but it is the destruction of subsidiarity, solidarity, and family and country.

When will true social justice be achieved? Only when this evil doppelgänger is defeated. Indeed, one is tempted to parody the line famously attributed to Diderot, and reply: only when the last socialist is strangled with the entrails of the last sexual revolutionary. That’s meant as a joke, of course. Revolutionary bloodlust is itself yet another malign legacy of the French Revolution, which every conservative and natural law theorist ought to condemn. But all the same: Écrasez l'infâme.

Related posts:

Cardinal virtues and counterfeit virtues

Poverty no, inequality si

Love and sex roundup

The conservative critique of libertarianism

Conservatism, populism, and snobbery

Published on October 10, 2017 19:36

October 8, 2017

Coming to a campus near you

On Thursday, October 19, I will be giving a talk on the topic of scientism at UC Berkeley, sponsored by the Thomistic Institute. Details available at the Institute’s website and at Facebook.

On Thursday, October 19, I will be giving a talk on the topic of scientism at UC Berkeley, sponsored by the Thomistic Institute. Details available at the Institute’s website and at Facebook. On Saturday, November 4, I will be giving a talk on the topic of conscience, at a conference devoted to that theme at Holy Rosary Parish in Portland, Oregon. Conference details here.

On Saturday, November 11, Joe Bessette and I will participate in a panel discussion of our book By Man Shall His Blood Be Shedat the annual Fall Conference put on by the Center for Ethics and Culture at Notre Dame.

On Friday, December 1, I will be giving a talk on the subject of scientism at Cal Tech in Pasadena, sponsored by Science and Faith Examined. More details to come.Further talks around the country are scheduled for next year and will be announced before long. Stay tuned.

Published on October 08, 2017 18:14

October 4, 2017

Reading Religion on By Man

At Reading Religion, a publication of the American Academy of Religion, Daniel Lendman reviews

By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed: A Catholic Defense of Capital Punishment

, which I co-authored with Joseph Bessette. From the review:

At Reading Religion, a publication of the American Academy of Religion, Daniel Lendman reviews

By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed: A Catholic Defense of Capital Punishment

, which I co-authored with Joseph Bessette. From the review: By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed provides a trenchant and cogent presentation of the defense of capital punishment from a Catholic perspective… Feser and Bessette… insist that the legitimacy of capital punishment is the ancient and long standing teaching of the Catholic Church. [They] go even farther, laying out a compelling case that denying that capital punishment can be legitimate in principle is proximate to heresy…While the context of this argument is decidedly and purposefully Catholic, readers of different religions and belief systems can still find forceful natural law arguments supporting capital punishment in this book. The authors also offer arguments claiming the prudence of using capital punishment in the United States, relying on case studies and statistical analysis. Anyone who is interested in investigating the question of the legitimacy of the use of capital punishment, especially in the United States, would do well to entertain the many and powerful arguments put forth by Feser and Bessette.

End quote. Lendman also remarks:

Readers should be warned, however, that there are many disturbing accounts about the crimes committed by those who have been put to death in the US. While this reviewer acknowledges that it seems to be a necessary part of the conversation, nevertheless, the sensitive would do well to steer clear of those sections.

End quote. That is a fair enough comment. However, I think it is worth mentioning that Joe and I were actually very restrainedin what we decided to put in the book. Some of the details of the crimes we describe are far more gruesome and disturbing than what made it into the book.

There is an air of sanctimoniousness and sentimentality on the part of some opponents of capital punishment that can be maintained only by ignoring the actual details of the crimes for which offenders are typically executed. There is a tendency to treat murderers as if they are mostly like the Morgan Freeman character from Shawshank Redemption – scared and mixed-up lovable losers who never got a break in life and simply made some bad choices. This is Hollywood, not reality. The extreme, unimaginable depravity and sadism of the worst murderers – and the fact that anything less than a penalty of death would be a mockery of justice and an insult to the victims and their families – is evident only when one takes note of exactly what they did. Hence the details Joe and I decided to put in the book.

Published on October 04, 2017 18:06

October 2, 2017

Five Proofs on The Daily Wire

Last week I did a Skype interview with The Daily Wire’s Ben Shapiro. The interview has now been posted at Ben’s Facebook page. (You can also watch it on YouTube.) We talk about

Five Proofs of the Existence of God

, and also about free will and neuroscience.

Last week I did a Skype interview with The Daily Wire’s Ben Shapiro. The interview has now been posted at Ben’s Facebook page. (You can also watch it on YouTube.) We talk about

Five Proofs of the Existence of God

, and also about free will and neuroscience.

Published on October 02, 2017 17:28

Edward Feser's Blog

- Edward Feser's profile

- 331 followers

Edward Feser isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.