Edward Feser's Blog, page 66

June 27, 2017

It’s the next open thread

Here is your latest opportunity to converse about topics that have not arisen in the course of other combox discussions at this here blog. From neo-Kantianism to neo-conservatism, from mortal sin to imported gin, from the dubia cardinals to the Doobie Brothers – discuss whatever you like, within reason. Keep it civil, but for once you needn’t keep it on topic.By the way, you need not address comments or questions to me personally, because more likely than not I will not have time to respond. This is not an “Ask Ed anything” post, sorry. Talk amongst yourselves.

Here is your latest opportunity to converse about topics that have not arisen in the course of other combox discussions at this here blog. From neo-Kantianism to neo-conservatism, from mortal sin to imported gin, from the dubia cardinals to the Doobie Brothers – discuss whatever you like, within reason. Keep it civil, but for once you needn’t keep it on topic.By the way, you need not address comments or questions to me personally, because more likely than not I will not have time to respond. This is not an “Ask Ed anything” post, sorry. Talk amongst yourselves.

Published on June 27, 2017 11:39

Fr. Z on By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed

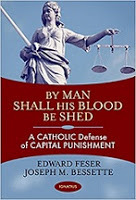

The esteemed Fr. John Zuhlsdorf kindly calls his readers’ attention to

By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed: A Catholic Defense of Capital Punishment

, my new book co-written with Joseph Bessette. Fr. Z writes:

The esteemed Fr. John Zuhlsdorf kindly calls his readers’ attention to

By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed: A Catholic Defense of Capital Punishment

, my new book co-written with Joseph Bessette. Fr. Z writes: Anything written by Edward Feser is reliable and worth time… This is a good book for the strong reader, student of Catholic moral and social teaching, seminarians and clerics.

Published on June 27, 2017 10:17

June 21, 2017

Arguments from desire

On his radio show yesterday, Dennis Prager acknowledged that one reason he believes in God – though not the only one – is that he wantsit to be the case that God exists. The thought that there is no compensation in the hereafter for suffering endured in this life, nor any reunion with departed loved ones, is one he finds just too depressing. Prager did not present this as an argument for the existence of God or for life after death, but just the expression of a motivation for believing in God and the afterlife. But there have, historically, been attempts to develop this idea into an actual argument. This is known as the argument from desire, and its proponents include Aquinas and C. S. Lewis.An obvious objection to any such argument would be that it is manifestly delusional to suppose that something is real simply because we want it to be. After all, the frustration of desire happens all the time – unrequited love, failed careers, empty stomachs, and so forth. Yet you might suspect that, precisely because this objection is soobvious, it must be missing something – that proponents of the argument from desire are not in fact reasoning in so crude and manifestly fallacious a way. And if so, you’d be right.

On his radio show yesterday, Dennis Prager acknowledged that one reason he believes in God – though not the only one – is that he wantsit to be the case that God exists. The thought that there is no compensation in the hereafter for suffering endured in this life, nor any reunion with departed loved ones, is one he finds just too depressing. Prager did not present this as an argument for the existence of God or for life after death, but just the expression of a motivation for believing in God and the afterlife. But there have, historically, been attempts to develop this idea into an actual argument. This is known as the argument from desire, and its proponents include Aquinas and C. S. Lewis.An obvious objection to any such argument would be that it is manifestly delusional to suppose that something is real simply because we want it to be. After all, the frustration of desire happens all the time – unrequited love, failed careers, empty stomachs, and so forth. Yet you might suspect that, precisely because this objection is soobvious, it must be missing something – that proponents of the argument from desire are not in fact reasoning in so crude and manifestly fallacious a way. And if so, you’d be right. Hence, consider Aquinas’s argument from desire for the immortality of the soul. One version can be found in Summa Theologiae I.75.6:

[E]verything naturally aspires to existence after its own manner. Now, in things that have knowledge, desire ensues upon knowledge. The senses indeed do not know existence, except under the conditions of "here" and "now," whereas the intellect apprehends existence absolutely, and for all time; so that everything that has an intellect naturally desires always to exist. But a natural desire cannot be in vain. Therefore every intellectual substance is incorruptible.

Another, longer version can be found in Summa Contra Gentiles II.55.13.

Now, notice first that Aquinas does not say that just any old desire is bound to be satisfied. What he says is that “a natural desire cannot be in vain.” Let’s consider both of the italicized parts of this statement.

First, by a “natural” desire, Aquinas means a tendency toward some end that a thing has just by virtue of being the kind of thing it is – that is to say, by virtue of its essence. (To put the point in more technical terms, he is talking about immanent final causes grounded in substantial forms.) So, consider a tree’s tendency to sink roots into the ground so as to take in water. That would be an example of the sort of thing Aquinas has in mind, and as that example indicates, a “desire” of the sort he is talking about needn’t be conscious. For a tree is not conscious, but it still “desires” water in the sense that by virtue of its nature it will send out roots so as to acquire it.

Human beings, of course, do consciously desire things, and sometimes what we consciously desire is some end toward which our nature moves us. Water would be an example here too. Given our animal nature, we need water and will seek it out. Some of our desires, however, are not “natural” in the relevant sense. For example, suppose I desire a copy of Captain America Comics #1. That would not be an unnatural desire, to be sure, but neither is there anything in my nature that directs me toward that particular end. Simply qua human being, I will not be directed toward the end of acquiring a copy of that comic book, in the way that I am qua human being directed toward the end of acquiring water.

However, some desires can also be positively unnatural. A strong desire not to drink water would be an example -- illustrated by the woman in the movie Ed Wood who claims to be allergic to it. A real-life and only slightly less bizarre example would be the woman with a compulsion to eat household cleanser. Less extreme examples of strange compulsions, habituated vices, etc. are familiar from everyday life. As such cases illustrate, that a desire is very strong and deep-rooted does not suffice to make it “natural” in Aquinas’s sense.

What does Aquinas mean when he says that a natural desire cannot be “in vain”? He can’t mean that such desires are always in fact satisfied, because he is as aware as his readers are that they are very often not satisfied. For example, trees, people, and other plants and animals die of thirst all the time. What he means is that a thing couldn’t naturally be directed toward some end unless that end were real. Such desires can be fulfilled at least in principle even if they are not always fulfilled in fact. Hence if trees, human beings, and other plants and animals are naturally directed toward seeking out water, there must really be water out there for them to seek (even if they don’t always find it). If there were not, the desire for water would be in vain.

So, to refute the key premise that Aquinas’s argument rests on, it will not suffice to find examples of unfulfilled desires, or even unfulfilled natural desires – which are, of course, so easy to come by that it should be obvious even to the hostile reader that that is not what Aquinas had in mind. What one would need is an example of a desire that is both “natural” in Aquinas’s sense and also “in vain” in the sense of being unfulfillable in principle because its object is unreal. And examples of that sort of thing are far from obvious.

Indeed, even people who would not think of themselves as sympathetic to Aristotelianism or Thomism will essentially apply Aquinas’s principle without realizing they are doing so. For example, if a paleontologist digs up the remains of a heretofore unknown species of animal and finds that it has many long, sharp teeth, he will suppose that there must have been living in this animal’s environment other kinds of animal that it preyed upon, even if the paleontologist has no independent evidence of such other animals. For otherwise, the animal’s possession of such carnivorous teeth would be in vain. (And even if it were finally judged that the carnivorous teeth are vestigial, this doesn’t affect the basic point, because even in that case they would have originally existed for meat-eating purposes.)

Now, what Aquinas does in his argument from desire is to add to this premise about natural desires a further consideration about human nature, specifically. Other animals have only sensory knowledge, which is directed toward the here and now. Human beings, by contrast, are rational animals, and their sort of knowledge – intellectual knowledge, which involves the grasp of universal concepts and universal truths – is directed beyond the here and now, indeed toward “all time.” But whatever is like this, Aquinas says, “naturally desires always to exist.” In the Summa Contra Gentiles passage, he says that creatures with intellects “know and apprehend perpetual being [and] desire it with natural desire” (emphasis added). Hence we must have perpetual being, or our desire for it would be in vain.

Needless to say, even given the qualifications I’ve made, this argument needs further spelling out if it is to be convincing. And an objection raised by John Duns Scotus might seem at first glance to torpedo it. He writes:

As for the proof that man has a natural desire for immortality because he naturally shuns death, it can be said that this proof applies to the brute animal as well as to man. ( Philosophical Writings , p. 159)

Scotus’s point is that if such a proof would fail in the case of brute animals (which it certainly would in Aquinas’s view, since he denies that such animals have immortal souls), then it must fail in the case of human beings as well.

Now, a non-human animal will, no less than a human being, be inclined as long as it exists to try to keep itself in existence. Scotus is right about that. But it doesn’t follow that brute animals have the same desire that Aquinas is attributing to human beings. To see why not, you need to get your Scotus on and draw a distinction. Consider the two claims:

(1) X always has a desire to preserve itself.

(2) X has a desire to preserve itself always.

(1) is true of brute animals, but (1) does not entail (2) and (2) is what Aquinas says is true of human beings but not true of brute animals. It is only if we blur the distinction between (1) and (2) that brute animals will seem to have the same desire Aquinas attributes to us.

But Scotus also raises a more challenging objection. In order to know that a thing has a natural desire to preserve itself always, we first have to establish that it has a natural capacity for perpetual existence. And if we knew that, we would already know that it is immortal, which would make an argument from desire redundant (Philosophical Writings, pp. 158-9).

Scotus is, I think, correct that a natural desire D presupposes a natural capacity C. But once again – the Subtle Doctor would be pleased – we need to draw a distinction. Even if the existence of D presupposes the existence of C, it doesn’t follow that knowledge of the existence of D presupposes knowledge of the existence of C. That is to say, the presupposition in question is metaphysical but need not be epistemological.

Consider, once again, the paleontology example. The existence of carnivorous teeth presupposes, in a metaphysical sense, the existence of prey who might be eaten. The former would not exist unless the latter did, whereas the latter could exist whether or not the former did. But it doesn’t follow that our paleontologist would first have independently to establish the existence of the relevant sort of prey in the environmental niche in question before judging that the teeth serve a carnivorous end. His general knowledge of the kinds of teeth there are suffices for that. Hence, if all he knows at first is that a certain environmental niche was populated by a kind of animal having carnivorous teeth, he can go on to conclude that there must also have been prey of the relevant sort living in that niche. He does not have to remain agnostic on that question pending direct evidence. The presupposition in question is not an epistemological one.

In the same way, Aquinas can argue that there is a natural desire for perpetual existence – and he does so on the basis of the nature of intellectual (as opposed to merely sensory) knowledge – and then go on to conclude that there must be a natural capacity for such existence. Knowledge of the desire can be prior to knowledge of the capacity, even if the capacity itself is metaphysically prior to the desire.

So, does Aquinas’s argument work? I think that when all the relevant metaphysical background theses and the subsidiary arguments are spelled out thoroughly – and I haven’t addressed all of that here – it plausibly does work. However, anyone who is convinced of the soundness of that larger body of philosophical claims is also likely already to be convinced of the immortality of the soul by other and more straightforward Thomistic arguments. So, while Aquinas’s argument from desire is a useful and illuminating part of the overall Thomistic view of things, it isn’t the most effective standaloneargument for immortality.

Compare the situation with Aquinas’s Fourth Way of arguing for God’s existence. I defend the Fourth Way, along with the rest of the Five Ways, in my book Aquinas . But one has to do so much general metaphysical stage-setting in order properly to understand how the argument works that, for purposes of establishing God’s existence, it is much more efficient to use a relatively more streamlined argument like one of the other Ways. Once one is independently convinced of the overall Thomistic system, the Fourth Way provides a very important and illuminating part of the story. But it’s not a good way to break into the system.

Or at least this is the case given the situation that happens to exist in contemporary philosophy. In a context where broadly classical (Platonic or Aristotelian) metaphysical presuppositions were widely accepted, arguments like the argument from desire or the Fourth Way would be much more plausible standalone arguments. But when those larger background presuppositions are not taken for granted and are even treated with some hostility, it is generally more effective to make use of other arguments.

Published on June 21, 2017 11:15

June 17, 2017

Surf dat web

A lecture by David Oderberg answering the question: Should there be freedom of dissociation?

A lecture by David Oderberg answering the question: Should there be freedom of dissociation? Philosopher of physics Tim Maudlin defends the reality of time and change, at Quantamagazine.

At The Weekly Standard, Camille Paglia on Trump, transgenderism, and terrorism.

Why is there more disagreement in philosophy than in science? Maybe because philosophy is just harder, suggests David Papineau in the Times Literary Supplement.Ross and Kripke revisited: In a YouTube video, Peter Dillard responds to my recent post responding to his ACPQarticle.

Joshua Hochschild on Jean-Paul Sartre’s La Nausée, at First Things.

The Dialogos Institute is hosting a colloquium on the doctrine of Limbo in Ramsgate, England later this month.

The continuing travails of Marvel Comics: Social justice warriors are burning their comics. A politically driven series is cancelled due to poor sales. Bad business decisions are taking a toll across the line.

The Guardian asks: What was it like to be Richard Wagner?

And what about his buddy Friedrich Nietzsche? Times Literary Supplement on some recent books.

At City Journal, Theodore Dalrymple on Paul Hollander on why so many intellectuals love dictators.

In the International Journal for Philosophy of Religion, Ben Page proposes an answer to the Euthyphro dilemma.

Politico on why liberals aren’t as tolerant as they think they are.

In related news: Duke theology professor Paul Griffiths, facing disciplinary action for calling diversity training a waste of time, has resigned.

More related news: Mark Steyn on the poisoning of Jihad Watch’s Robert Spencer by social justice warriors.

Yet more related news: At Bleeding Heart Libertarians, Jason Brennan on the latest attack on free expression within academic philosophy.

Raymond Tallis on time and physics, Daniel Robinson, Luciano Floridi, and Murillo Pagnotta on information, Stephen Talbott on evolution and purpose, and more in the latest issue of The New Atlantis.

At Public Discourse, philosopher John Skalko on why there are only two sexes.

Michael Pakaluk on Trump, Pope Francis, and the Paris climate agreement: How should Catholics respond?

Gregory Reichberg’s Thomas Aquinas on War and Peace is reviewed atNotre Dame Philosophical Reviews.

Boston Review on a new book on the obsessions of Hitchcock, Welles, and Kubrick.

Quartz asks: Was Descartes’ most famous idea anticipated by St. Teresa of Avila?

Every Catholic theologian and philosopher should own a copy. At Rorate Caeli, Peter Kwasniewski reports on a new reprint of Scheeben’s classic work of Thomistic theology.

At the APA blog, video of a discussion with philosopher Nancy Cartwright and physicists George Ellis and Michael Duff on causality and unexplained events.

According to Catholic World Report, Thomas Aquinas College is looking to open a campus in Massachusetts.

The sexual revolution eats its own. Maggie Gallagher at The Stream on a new controversy over Lou Reed’s “Walk on the Wild Side.”

At First Things, Matthew Schmitz argues that Pope Francis is burying Pope Benedict.

At Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews, Tom Christiano reviewsJason Brennan’s Against Democracy.

At Thomistica.net, Robert Barry on how to listen to heretics before burning them.

Graham Oppy on William Lane Craig’s God Over All: Divine Aseity and the Challenge of Platonism, at Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews.

Published on June 17, 2017 13:41

June 12, 2017

Stroud on Hume

David Hume, as I often argue, is overrated. But that’s not his fault. It’s the fault of those who do the overrating. So, rather than beat up on him (as I have done recently), let’s beat up on them for a change. Or rather, let’s watch Barry Stroud do it, in a way that is far more genteel than I’m inclined to.The problem, as I’ve often pointed out, is this. Hume’s most famous conclusions – his skepticism about induction, his treatment of causality, his subjectivism about value, and so forth – are widely celebrated by contemporary philosophers. Even those philosophers who don’t agree with these conclusions tend to regard them as formidable. Yet few if any of these philosophers would accept the basic philosophical presuppositions on which Hume’s conclusions all rest. For example (and as I often complain), Hume conflates concepts with mental imagery. That is a very crude philosophical error, it has been known to be a crude error since at least Plato and Aristotle, and it has been known to contemporary philosophers to be a crude error since at least Wittgenstein. There is very little if any “punch” left to Hume’s philosophy once this error is exposed. Yet his conclusions continue to be taken seriously long after such underpinnings have collapsed. They are like a ghost that continues to walk the earth long after the death of the body.

David Hume, as I often argue, is overrated. But that’s not his fault. It’s the fault of those who do the overrating. So, rather than beat up on him (as I have done recently), let’s beat up on them for a change. Or rather, let’s watch Barry Stroud do it, in a way that is far more genteel than I’m inclined to.The problem, as I’ve often pointed out, is this. Hume’s most famous conclusions – his skepticism about induction, his treatment of causality, his subjectivism about value, and so forth – are widely celebrated by contemporary philosophers. Even those philosophers who don’t agree with these conclusions tend to regard them as formidable. Yet few if any of these philosophers would accept the basic philosophical presuppositions on which Hume’s conclusions all rest. For example (and as I often complain), Hume conflates concepts with mental imagery. That is a very crude philosophical error, it has been known to be a crude error since at least Plato and Aristotle, and it has been known to contemporary philosophers to be a crude error since at least Wittgenstein. There is very little if any “punch” left to Hume’s philosophy once this error is exposed. Yet his conclusions continue to be taken seriously long after such underpinnings have collapsed. They are like a ghost that continues to walk the earth long after the death of the body. In his book Engagement and Metaphysical Dissatisfaction: Modality and Value , Stroud raises a similar complaint. Contemporary philosophers take Hume’s doubts about causality as a feature of mind-independent reality very seriously. Yet they do not accept either the account of perception that these doubts rest on, or some of the other conclusions Hume draws from that account. And it is not clear how they can consistently take the one without the others. Stroud writes:

Many philosophers of more recent times remain in a broad sense followers of Hume on the status of causation without accepting such a severely restricted conception of the scope of perception. They appear to hold that we can perceive and thereby have a conception of physical objects and other enduring things and states of affairs even though the idea of causal dependence between such things in the independent world remains problematic or metaphysically dubious. The source of their doubts is not easy to determine. One possible source is the assumption that we never perceive instances of causal connection or dependence. A different but related possibility is that causal dependence is thought to be unperceivable because of the doubtful intelligibility of the idea of such a connection. In any case, it certainly is still widely believed that we never perceive causal connections between things. By now the view is hardly ever argued for. The most that is usually offered in its support is a reverential bow in the direction of Hume, but with no acknowledgment of the restrictive theory of perception that Hume's own denial rests on. (p. 23)

Hume thinks of perception as the passive reception of “impressions” such as a sensation of color, a sharp pain, or a twinge of fear. “Ideas” in turn, as he uses the term, are faint copies of such impressions – essentially mental imagery of a visual, auditory, tactile, olfactory, or gustatory sort, along with memories of emotions and the like. Few philosophers today would endorse such a crude model of perceptual experience or concept formation. Yet that model underlies Hume’s doubts about causation as an objective feature of reality. We have a set of impressions (a succession of visual experiences of a round whitish patch, say) that we take to be the motion of a cue ball, followed by another set of impressions (a “knocking” sound followed by a succession of visual experiences of a round black patch) that we take to be the motion of an 8 ball. But we have no impression of a causal power or force by which the first generatesthe second. Hence we have no idea of such a force or causal power. We just find that impressions of the former sort are constantly conjoined in our experience with impressions of the latter sort. This leads us to expect the latter on the occasion of the former, and we projectthis subjective expectation onto the world. But we have, Hume claims, no reason to think it really corresponds to any objective feature of the world.

(On the “skeptical realist” reading of Hume, he does not intend to undermine our commonsense belief that there really are such causal features in external reality, but merely denies that we can have any cognitive grasp of them. But it’s hard to see how one could consistently push the latter point without ending up in essentially the more radical skeptical position traditionally attributed to Hume. I cannot myself help wondering whether the recent heavy going about “skeptical realism” among Hume interpreters might be much ado about not a whole helluva lot. But that’s neither here nor there for present purposes.)

Since contemporary philosophers wouldn’t buy this story about our perceptual and cognitive faculties, it’s hard to see why they remain impressed by the conclusions about causation Hume draws from them. That’s part of Stroud’s point. The other part of his point is that Hume draws other lessons from the same account of perception and cognition, lessons that contemporary philosophers are not so impressed by. In particular, Hume concludes that we have no idea of mind-independent physical objectseither, because he thinks we have no impression of such things. We have, for example, only this fleeting impression of a round whitish patch, that other fleeting impression of a round whitish patch, a fleeting impression of a “knocking” sound, etc., but no impression of any substance that underlies and ties together these different impressions. Here again we are in his view really just projecting onto the world something that is merely subjective, namely the brief relative stability of some of our impressions (where an impression is something essentially mental rather than mind-independent). This is the origin of our belief in mind-independent objects, and it has no more sound a basis than our belief in objective causal connections.

Now, contrary to what non-philosophers sometimes think, few contemporary philosophers really take seriously the idea that there are no mind-independent physical objects. They may regard it as an interesting puzzle, but not as a live option. The idea that objective causal power and necessity might not really exist is taken to be a live option, though. And what Stroud is puzzled by is why that should be the case given that the other Humean skeptical conclusion is not taken seriously.

Nor in Stroud’s view is it just the common Humean foundationof these two kinds of skepticism that makes this combination of attitudes problematic. That is to say, the problem is not just that Hume himself based his skepticism about causation and his skepticism about physical objects on the same flawed account of perception and cognition. It’s also that, even apart from that, it is hard to see how one could consistently believe in mind-independent physical objects without also attributing to them real causal powers. Stroud writes:

This raises a general question about how or whether a person could think about and understand the objects this view admits that we do see. Could we have a conception of a world of visible, enduring objects at all if we could never see what any of those objects do, or see them doing it? Hume's actual view does not face this difficulty. He thinks not only that we never see a stone break a window, but that we never see a stone or a window either. Hume acknowledges the need to explain how we get even so much as the idea of an enduring object from the fleeting perceptions we receive, and how we come to think of such things as perceivable. But for those who think we can see an object and know what it is and where it is and what will happen if certain other things happen, but that we never see the object doing or undergoing any of the things it does, there is a special problem. (p. 24)

What Stroud is appealing to here is the thesis – common to (though spelled out in very different ways by) both Kant-inspired writers like P. F. Strawson and contemporary neo-Aristotelians and Thomists – that we cannot make sense of the notion of a world of independently existing substances except as causally related in various ways. (Think of the Scholastic thesis agere sequitur esse or “action follows being” – that is to say, that how a thing acts reflects what it is. If a thing does nothing, then it cannot be said to have being at all; and if it does have being, then it must be capable of doing something, which entails causal power.)

If that’s correct – and obviously it’s a claim requiring elaboration and defense – then skepticism about mind-independent objects and skepticism about causation stand or fall together. As Stroud notes, Hume is at least consistent on this score, since he opts for skepticism in both cases. It’s the selective skepticism (and selective Humeanism) of some contemporary philosophers that Stroud thinks dubiously coherent.

But it’s not a universal tendency. Where causation is concerned, the Humean ghost is at long last being exorcised in some quarters, as evidenced by books like Mumford and Anjum’s Getting Causes from Powers and the neo-Aristotelian literature. (Naturally, I’ve tried to do my part as well.)

Published on June 12, 2017 22:30

June 9, 2017

Five Proofs is coming

Five Proofs of the Existence of God will be out this Fall. You can pre-order at the Ignatius Press website and at Amazon. Here’s the book jacket description:

Five Proofs of the Existence of God will be out this Fall. You can pre-order at the Ignatius Press website and at Amazon. Here’s the book jacket description: Five Proofs of the Existence of God provides a detailed, updated exposition and defense of five of the historically most important (but in recent years largely neglected) philosophical proofs of God's existence: the Aristotelian proof, the Neo-Platonic proof, the Augustinian proof, the Thomistic proof, and the Rationalist proof.This book also offers a detailed treatment of each of the key divine attributes -- unity, simplicity, eternity, omnipotence, omniscience, perfect goodness, and so forth -- showing that they must be possessed by the God whose existence is demonstrated by the proofs. Finally, it answers at length all of the objections that have been leveled against these proofs.

This book offers as ambitious and complete a defense of traditional natural theology as is currently in print. Its aim is to vindicate the view of the greatest philosophers of the past -- thinkers like Aristotle, Plotinus, Augustine, Aquinas, Leibniz, and many others -- that the existence of God can be established with certainty by way of purely rational arguments. It thereby serves as a refutation both of atheism and of the fideism which gives aid and comfort to atheism.

More information here. Some endorsements:

“A watershed book… Feser has completely severed the intellectual legs upon which modern atheism had hoped to stand.” Matthew Levering, James N. and Mary D. Perry Jr. Chair of Theology, Mundelein Seminary

“Edward Feser is widely recognized as a top scholar in the history of philosophy in general, and in Thomistic and Aristotelian philosophy in particular… Feser admirably achieves his goal, and Five Proofs of the Existence of God is a must read for anyone interested in natural theology. I happily and highly recommend it.” J. P. Moreland, Distinguished Professor of Philosophy, Biola University

“Yet another fine book by Edward Feser… Feser replies to (literally) all of the objections and shows convincingly how the most popular objections (the kind one hears in Introduction to Philosophy courses) are very often completely beside the point and, even when they’re not, are ‘staggeringly feeble and overrated’… Five Proofs of the Existence of God puts the lie to the common assumption among professional philosophers that natural theology was done in forever by the likes of Hume and Kant, never to rise again.” Alfred J. Freddoso, Professor Emeritus of Philosophy, University of Notre Dame

“Refutes with devastating effect the standard objections to theistic proofs, from David Hume to the New Atheists. Feser draws on the best from both scholastic and modern analytic philosophy, including persuasive defenses of the real distinction in creatures between essence and existence, the absolute simplicity of God, and the continued importance of causation in a relativistic and quantum-mechanical world.” Robert C. Koons, Professor of Philosophy, University of Texas at Austin

“A powerful and important book... The concluding chapter, where Feser replies to possible objections to his arguments, is a gem; it alone is worth the price of this excellent work.” Stephen T. Davis, Russell K. Pitzer Professor of Philosophy, Claremont McKenna College

Published on June 09, 2017 11:52

June 3, 2017

The curious case of Pope Francis and the “new natural lawyers”

The “new natural law theory” (NNLT) was invented in the 1960s by theologian Germain Grisez and has found prominent advocates in law professors John Finnis and Robert P. George. Other influential members of this school of thought include the philosophers Joseph Boyle and Christopher Tollefsen and the theologian E. Christian Brugger. The “new natural lawyers” (as they are sometimes called) have gained a reputation for upholding Catholic orthodoxy, and not without reason. They have been staunch critics of contraception, abortion, euthanasia, and “same-sex marriage.” However, the NNLT also departs in several crucial ways not only from the traditional natural law theory associated with Thomas Aquinas and the Thomistic tradition (which is what makes the NNLT “new”), but also from traditional Catholic moral theology.One notorious example concerns craniotomy and abortion. Again, NNLT writers are opposed to intentionally killing an unborn child. However, some of them have argued that crushing a fetus’s skull so as to remove it from the mother’s body and thereby end the pregnancy need not reflect an intention to kill the fetus even though this procedure will in fact kill it. It could reflect instead merely an intention to alter the shape of the fetus’s skull so as more easily to remove it, and in some cases be in principle justifiable (by the principle of double effect) on that basis. This reflects the NNLT’s distinctive analysis of intention, which is very different from the traditional Thomistic analysis, and (unsurprisingly) it has generated considerable controversy among Catholic moral theologians.

The “new natural law theory” (NNLT) was invented in the 1960s by theologian Germain Grisez and has found prominent advocates in law professors John Finnis and Robert P. George. Other influential members of this school of thought include the philosophers Joseph Boyle and Christopher Tollefsen and the theologian E. Christian Brugger. The “new natural lawyers” (as they are sometimes called) have gained a reputation for upholding Catholic orthodoxy, and not without reason. They have been staunch critics of contraception, abortion, euthanasia, and “same-sex marriage.” However, the NNLT also departs in several crucial ways not only from the traditional natural law theory associated with Thomas Aquinas and the Thomistic tradition (which is what makes the NNLT “new”), but also from traditional Catholic moral theology.One notorious example concerns craniotomy and abortion. Again, NNLT writers are opposed to intentionally killing an unborn child. However, some of them have argued that crushing a fetus’s skull so as to remove it from the mother’s body and thereby end the pregnancy need not reflect an intention to kill the fetus even though this procedure will in fact kill it. It could reflect instead merely an intention to alter the shape of the fetus’s skull so as more easily to remove it, and in some cases be in principle justifiable (by the principle of double effect) on that basis. This reflects the NNLT’s distinctive analysis of intention, which is very different from the traditional Thomistic analysis, and (unsurprisingly) it has generated considerable controversy among Catholic moral theologians.Another example is capital punishment. Scripture, the Fathers and Doctors of the Church, and a long line of popes have consistently affirmed that capital punishment can be legitimate in principle. Indeed, some popes have taught that it is contrary to Catholic orthodoxy to deny that capital punishment can in principle be legitimate. Even Pope John Paul II, who famously opposed capital punishment in practice, was careful explicitly to affirm that it can be legitimate at least in principle. It has, however, become the standard view among the “new natural lawyers” that capital punishment is in fact always and intrinsically wrong, wrong even in principle and not merely in practice under modern circumstances. Grisez started to promote this idea around 1970, and his followers have argued that the Catholic Church could reverse her consistent teaching on this subject and adopt Grisez’s novel doctrine instead.

This is delusional and dangerous. In our book By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed: A Catholic Defense of Capital Punishment , Joseph Bessette and I show, we think conclusively, that the legitimacy in principle of capital punishment is in fact an irreformable teaching of the Church. (Joe and I briefly summarized some key points in an article at Catholic World Report last year, but I urge the interested reader to consult chapter 2 of the book, which devotes well over 100 pages of documentation and analysis to the subject.) Any pope who tried to reverse this teaching would by that very fact put himself in that small company of popes who have taught doctrinal error, which Catholic teaching allows is possible when a pope is not speaking ex cathedra. He would also severely damage the credibility both of the Church and of himself. If Scripture, the Fathers and Doctors of the Church, and all previous popes could all be so wrong for so long about something that serious, why should anyone trust what the Church says about any other topic? And why should anyone trust a pope who contradicted his predecessors in this way? If they could all get things so badly wrong, why believe him?

Pope Francis and capital punishment

It might appear, however, that in Pope Francis, the “new natural lawyers” have found a pontiff who might be willing to move in their radically abolitionist direction. For the pope has sometimes made remarks that seem, at least at first glance and when read in isolation, to condemn capital punishment as intrinsically unjust.

To be sure, as Joe and I argue in our book, when read carefully it is clear that Pope Francis has not in fact quite said this. We devote a fair amount of space to analyzing the pope’s statements about capital punishment (see pp. 183-196), and we argue that when all his remarks are taken account of, it is evident that he does not in substance move beyond what Pope John Paul II taught.

However, rhetorically he has several times gone beyond John Paul II. For example, in 2015 he stated that “justice is never reached by killing a human being” and in 2016 he said that “the commandment ‘thou shalt not kill’ has absolute value and pertains to the innocent as well as the guilty” and that “even a criminal has the inviolable right to life” (emphasis added). Some of his remarks have been even more extreme. For example, in the 2015 statement he went so far as approvingly to quote a remark he attributed to Dostoevsky to the effect that “to kill a murderer is a punishment incomparably worse than the crime itself”(!)

Pope Francis has also not confined his negative remarks to capital punishment. He has several times also indicated that he regards even life imprisonment as immoral. For example, in 2014 he stated that “a life sentence is just a death penalty in disguise” and implied that opponents of the latter must therefore oppose the former as well. He repeated this in his 2015 remarks, criticizing sentences to life imprisonment as “hidden death sentences.” Not only does this go far beyond anything Pope John Paul II or any other previous pope said, it also conflicts with what other Catholic opponents of capital punishment say. For example, in a 2005 document the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops recommended “life without the possibility of parole” as an alternative to capital punishment.

Again, as Joe and I show in the book, Pope Francis has also said things that point away from a condemnation of capital punishment as intrinsically immoral. For example, in the 2015 statement he also says that the “elimination” of an aggressor is sometimes “necessary,” and that “today capital punishment is unacceptable,” indicating that it was legitimate in the past and under different circumstances.

Then there is the fact that some of his remarks are soextreme that a charitable reader would have to conclude that the pope is in general speaking with rhetorical flourish rather than intending to make careful doctrinal remarks. Consider the statement that the death penalty is “incomparably worse than” the crimes for which an offender might be executed. Taken at face value, this remark is preposterous, indeed obscene. To take just one example, Ted Bundy murdered fourteen women, routinely raped and tortured his victims, and mutilated and even engaged in necrophilia with their bodies. He was executed in the electric chair, a method of killing that takes only a few moments. Does any sane person really believe that executing Bundy was “incomparably worse than” what Bundy himself did?

Or consider the claim that life imprisonment ought also to be abolished. Is the pope telling us that serial killers and mass murderers like Charles Manson, Richard Allen Davis, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, et al. ought to be let out of prison? Presumably not. But then, what exactly does he mean? Presumably he is merely expressing in a rhetorically extreme way the view that life imprisonment can be morally problematic, even if it is not always and in itself wrong.

If these remarks are to be read as mere rhetorical flourishes, though, then it is plausible that the pope’s other remarks about capital punishment are to be read as rhetorical, rather than as expressions of the view that capital punishment is always and in principle wrong. Again, Joe Bessette and I defend this interpretation at length in our book.

All the same, it would by no means be surprising if “new natural lawyers” appealed to at least some of Pope Francis’s statements on capital punishment as evidence of papal support for their extreme abolitionist position. Yet to my knowledge, they have not done this. They have not said: “Pope Francis has now taught that even a criminal’s right to life is inviolable and that the fifth commandment applies to the guilty as well as to the innocent! This is nothing less than a papal seal of approval on what we ‘new natural lawyers’ have been saying for decades!”

This is very odd. Critics have for years been accusing NNLT advocates of contradicting irreformable Catholic doctrine and of taking Pope John Paul II’s teaching on capital punishment in an extreme direction that he did not take it himself. Now Pope Francis has, at least on a surface reading, given them ammunition. Yet they have not used it. Why not?

Pope Francis and the “new natural lawyers”

The answer, I conjecture, is that the “new natural lawyers” have found Pope Francis’s remarks on other doctrinal matters to be so distressing that they are reluctant to appeal to him on this one.

Consider first Grisez’s response to the pope’s famous 2013 interview with Fr. Antonio Spadaro (the one in which the pope said, among other things, that the Church shouldn’t be “obsessed with the transmission of a disjointed multitude of doctrines to be imposed insistently“). Commenting on one of the remarks the pope made in that interview, Grisez said:

[I]f it was suggested by a spirit, it was not the Holy Spirit, for it is bound to confuse and mislead.

I’m afraid that Pope Francis has failed to consider carefully enough the likely consequences of letting loose with his thoughts in a world that will applaud being provided with such help in subverting the truth it is his job to guard as inviolable and proclaim with fidelity. For a long time he has been thinking these things. Now he can say them to the whole world – and he is self-indulgent enough to take advantage of the opportunity with as little care as he might unburden himself with friends after a good dinner and plenty of wine.

End quote. That’s pretty strong language – and note that Grisez made these remarks even before Pope Francis made his most controversial utterances.

Coming to those, consider next the pope’s remarks last year about the use of contraception as a way of dealing with the Zika virus. Two NNLT advocates, Tollefsen and Brugger, have argued (plausibly in my view) that the pope’s statements are morally problematic and cannot be reconciled with Catholic teaching on contraception.

Then there is the problematic nature of Pope Francis’s statements in Amoris Laetitia and elsewhere about divorce, remarriage, and Holy Communion (about which I have written not too long ago). Brugger has raised worries about these statements in a series of articles (here, here, here, and here). Grisez and Finnis have called on Pope Francis to condemn certain errors that are being propagated in the name of Amoris.

It may be, then, that the “new natural lawyers” have come to regard Pope Francis’s Magisterium as too problematic in general to be useful to appeal to in defense of their position on capital punishment. That is speculation on my part, but it would explain the otherwise puzzling failure of NNLT writers to trumpet the pope’s statements on that subject. There is rich irony here. For decades NNLT advocates have been waiting for a pope who would adopt their extreme never-even-in-principle position on the death penalty. Yet when they finally get a pope who at least arguably comes close to this, he ends up saying things on other topics that they find highly alarming. It must be very frustrating for them.

New unnatural loopholes

I can’t say I feel their pain, however. For there is another rich irony here – namely that the “new natural lawyers’” position on capital punishment is, frankly, far more obviouslyin conflict with Catholic tradition than anything Pope Francis has said. Not to put too fine a point on it, it takes real chutzpah for writers whose position implies that scripture, the Fathers and Doctors of the Church, and 2000 years of papal teaching have all been gravely in error to complain that Pope Francis has broken with Catholic tradition!

The pope has, after all, claimed that his most controversial remarks are perfectly in harmony with tradition, and to some extent has even tried to justify this claim. For example, he cited an alleged policy of Pope Paul VI when attempting to justify his remarks about Zika and contraception. Amoriscites Gaudium et Spes in support when it appears to suggest that the good of the children produced by adulterous unions might be endangered if “certain expressions of intimacy are lacking.” I do not say that these particular appeals to tradition are plausible – I think they are not plausible – but again, it is at least claimed that there is no rupture with tradition.

Compare that with Brugger’s book Capital Punishment and Roman Catholic Moral Tradition , which is by far the most detailed treatment of the subject written from a NNLT point of view. It is a very curious document. In particular, it is striking how much Brugger concedes to those who claim that the NNLT position is a radical break with traditional Catholic teaching.

For example, Brugger admits that the attempts of theologians who oppose capital punishment to reinterpret passages like Genesis 9:6 (“Whoever sheds the blood of man, by man shall his blood be shed; for God made man in his own image”) are unconvincing. He admits that the passage poses a “problem” for positions like his own, which is “left standing” even given the creative exegesis of modern biblical scholars.

While some have claimed that Church Fathers like Tertullian and Lactantius were opposed even in principle to capital punishment, Brugger also admits that this is not the case. Indeed, he admits that there was a “Patristic consensus” on the legitimacy in principle of capital punishment (even if some Fathers opposed it in practice).

Brugger admits that when Pope Innocent III required the Waldensian heretics to affirm, as a matter of Catholic orthodoxy, that capital punishment can be inflicted without mortal sin, what the pope meant is that the punishment itself can be legitimate. Brugger thereby disagrees with Grisez, who has tried to reinterpret Innocent III’s teaching as concerned only with subjective culpability for the act of execution rather than with the moral status of the act itself.

Brugger admits that modern abolitionism has its roots in philosophical ideas and social movements hostile to Catholicism, such as the thought of Voltaire, Hume, and Bentham, in social contract theory and utilitarianism, in the loss of belief in an afterlife and consequent emphasis on prolonging this life, and in Enlightenment and secularist thinking in general. He admits that the experience of Catholic pastors shows that the prospect of execution often leads offenders to repentance and conversion.

Brugger admits that even Pope John Paul II, despite his opposition in practice to most executions, explicitly taught that capital punishment is legitimate in principle. He admits that what he calls the “plain-face interpretation” of the 1997 update of the Catechism of Catholic Church does not support even the claim that a development of doctrine has taken place, much less a reversal of past teaching. In the new edition of his book, Brugger also admits that Pope Benedict XVI would probably not agree with any attempt to construct from John Paul II’s teaching a more radically abolitionist position (as Brugger tries to do).

In general, Brugger admits that scripture, tradition, and the history of papal teaching have consistently supported the legitimacy in principle of capital punishment, and compiles a mountain of evidence to that effect. Rare is the author who so thoroughly if inadvertently undermines his own case.

And yet he does try to make that case. That is to say, Brugger attempts, in the face of all this evidence to the contrary, to show that the NNLT thesis that capital punishment is always and intrinsically wrong, wrong even in principle and not merely in practice, is compatible with Catholicism. The attempt involves two basic lines of argument. First, Brugger claims that while the Church has always taught that capital punishment is legitimate in principle, she has not done so in a strictly irreformable way. Second, he claims that even though Pope John Paul II did not explicitly teach that capital punishment is immoral in principle (and indeed explicitly taught the opposite), such a teaching is nevertheless implicitin some of the things he said.

Now, in By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed, Joe and I examine these lines of argument in detail, and we show that they are completely without merit. Indeed, you will find in our book the most thorough response yet given to Brugger and other NNLT writers on capital punishment.

I direct readers interested in a critique of the NNLT position to our book, then. The point I want to emphasize for present purposes is this: By Brugger’s own admission, the NNLT position on capital punishment is radically discontinuouswith what the Church has traditionally taught, has not yet been shown to be reconcilable with scripture, and requires departing from the “plain-face interpretation” even of the magisterial texts most favorable to it. How is that any better than what the “new natural lawyers” find troubling in some of Pope Francis’s statements (which at least claim to be in continuity with tradition)? How can it be permissible for NNLT advocates to ignore the “plain-face interpretation” of John Paul II’s statements in Evangelium vitae in favor of some purportedly deeper new doctrine vis-à-vis capital punishment, if it is impermissible for even a pope to ignore the “plain-face interpretation” of John Paul II’s statements in Familaris consortio in favor of a purportedly deeper new understanding of Holy Communion for the divorced and remarried? Why do the “new natural lawyers” get a pass if Pope Francis doesn’t?

In fact what NNLT advocates worry that they see in Pope Francis and his defenders is something they have for decades been practicing themselves – “lawyering” in the sense of looking for loopholes in Catholic tradition by which some novel doctrine might be introduced into it, and by which the novelty might be acquitted of the charge of heterodoxy on a technicality. On the back cover of the first edition of Brugger’s book, a blurb from Grisez tells us that Brugger “defends the proposition that the Catholic Church could teach that capital punishment is always morally wrong” (emphasis added). But looking for ways by which the Church “could teach” such-and-such is a very odd way of doing Catholic theology. One would have thought that the idea was rather to find out what the Church doesin fact teach. After all, as the First Vatican Council declared:

For the Holy Spirit was promised to the successors of Peter not so that they might, by his revelation, make known some new doctrine, but that, by his assistance, they might religiously guard and faithfully expound the revelation or deposit of faith transmitted by the apostles.

The theologian’s business, the “new natural lawyers” would rightly warn us, is not to remake Catholicism in the image of Walter Kasper’s personal theology. But neither is it to remake Catholicism in the image of Germain Grisez’s personal theology. The disease the NNLT writers diagnose is one they have played no small part in spreading themselves.

Published on June 03, 2017 16:52

May 25, 2017

Catholic Herald on capital punishment

The latest issue of the Catholic Herald features an article by Dan Hitchens on Catholicism and the death penalty which discusses

By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed: A Catholic Defense of Capital Punishment

, which I co-authored with political scientist Joseph Bessette and which has just been released by Ignatius Press. The article contains some remarks from a brief interview I did with the Herald. This follows upon another recent Catholic Herald article by Marc Mason on the same subject.

The latest issue of the Catholic Herald features an article by Dan Hitchens on Catholicism and the death penalty which discusses

By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed: A Catholic Defense of Capital Punishment

, which I co-authored with political scientist Joseph Bessette and which has just been released by Ignatius Press. The article contains some remarks from a brief interview I did with the Herald. This follows upon another recent Catholic Herald article by Marc Mason on the same subject.

Published on May 25, 2017 18:53

When is a university not a university?

Some readers may by now have heard about what is happening at the University of St. Thomas in Houston, where the university president’s actions have put the philosophy faculty in fear for their jobs and for the survival of their program. Details are available at Daily Nous (with a follow-up here) and at Inside Higher Ed. Philosophers at the University of Notre Dame have issued a statement on the controversy. John Hittinger at the University of St. Thomas has started a GoFundMe campaign to raise money for a legal defense.I have nothing to state but the obvious: A university without a philosophy program is not a true university. A Catholic university without a philosophy program is not a truly Catholic university. A university named after St. Thomas Aquinas without a philosophy program is too stupid for words. And if you really need all this explained to you, then you have no business running a university.

Some readers may by now have heard about what is happening at the University of St. Thomas in Houston, where the university president’s actions have put the philosophy faculty in fear for their jobs and for the survival of their program. Details are available at Daily Nous (with a follow-up here) and at Inside Higher Ed. Philosophers at the University of Notre Dame have issued a statement on the controversy. John Hittinger at the University of St. Thomas has started a GoFundMe campaign to raise money for a legal defense.I have nothing to state but the obvious: A university without a philosophy program is not a true university. A Catholic university without a philosophy program is not a truly Catholic university. A university named after St. Thomas Aquinas without a philosophy program is too stupid for words. And if you really need all this explained to you, then you have no business running a university.

Published on May 25, 2017 18:34

May 23, 2017

Peters on By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed

By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed: A Catholic Defense of Capital Punishment

, which I co-authored with political scientist Joseph Bessette, is now available. Edward Peters, Professor of Canon Law at Sacred Heart Major Seminary, comments today at Facebook:

By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed: A Catholic Defense of Capital Punishment

, which I co-authored with political scientist Joseph Bessette, is now available. Edward Peters, Professor of Canon Law at Sacred Heart Major Seminary, comments today at Facebook: Since I first saw it in galley form several months ago I have been impatiently awaiting the [book’s] publication… Well, my copy just arrived in the mail.

Defenders of the death penalty for certain heinous offenses need no encouragement from me to study this book, of course, but, from now on, opponents of the death penalty who do not address the arguments set out by Feser & Bessette really have nothing useful to contribute to the debate.After reading said galley, Prof. Peters provided an endorsement for the book, the full text of which is as follows:

Feser and Bessette’s defense of capital punishment is a triumph of truth over platitude, of fact over fiction, of argument over emotion. In response to recent condemnations of the death penalty issued by various ecclesiastics, Feser and Bessette calmly and methodically set forth the philosophical, Scriptural, doctrinal, and sociological arguments grounding the Catholic Church’s hitherto unquestioned – and ultimately unquestionable – support for the death penalty when it is justly administered. Defenders of capital punishment will find in these pages persuasive arguments upholding the proper exercise of this momentous state power and opponents of the death penalty will see their challenges accurately depicted and soberly answered. From this point on, all contributions to the capital punishment debate, especially as conducted by and among Catholics, must incorporate the work of Feser and Bessette or risk irrelevance.

Joe and I thank Prof. Peters for his very kind words. If you’re not familiar with Prof. Peters’ fine blog, you should be.

Interested readers can find other endorsements of the book at my main web page.

Published on May 23, 2017 21:34

Edward Feser's Blog

- Edward Feser's profile

- 331 followers

Edward Feser isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.