Edward Feser's Blog, page 40

March 28, 2020

Craig, conventionalism, and voluntarism

At his personal Facebook page and also at the Reasonable Faith Facebook page, William Lane Craig briefly comments on my First Things review of his book

God Over All

. Bill says:

At his personal Facebook page and also at the Reasonable Faith Facebook page, William Lane Craig briefly comments on my First Things review of his book

God Over All

. Bill says:For our philosophically inclined readers who are interested in divine aseity and Platonism, here's a great little philosophical exercise: Where does this review by Ed Feser go wrong? (Hint: do I hold that mathematical truth is conventional? Why think I should?) End quote. Bill evidently thinks I have misunderstood him. However, it seems he has misunderstood me. I neither said nor implied in my review that Bill is a conventionalist about mathematics. What I did say – and I put great emphasis on the point and developed it at some length – is that his position is in danger of collapsing into a kind of divine voluntarism about mathematics. It isn’t human convention, but divine arbitrary stipulation, that seems in his view to be the foundation of mathematical truth.

Mind you, I also made it clear that I don’t think Bill wantsto end up with such a voluntarist position either. But I think his view inadvertently opens the door to voluntarism, for reasons I spell out in the review. I also explain why I think this is a problem.

As near as I can tell, Bill’s misunderstanding is based on a line in the review where I say: “For the Aristotelian, the Platonist is correct to regard mathematics as a description of objective reality rather than as mere linguistic convention.”

But it would be a mistake to infer from that line that I think that Bill takes a conventionalist view about mathematics. Again, I didn’t think that and I wasn’t saying that. First, the context in which that remark occurs is a general explanation of what an Aristotelian approach to mathematics involves and how it contrasts with the best-known alternative positions. The line in question wasn’t meant to contrast the Aristotelian position with Bill’s views, specifically, but rather to contrast it with the best-known versions of anti-realism.

Second, I now see that what I originally wrote had been slightly altered by the copy editor in a way that, unfortunately, I overlooked when I went over the proofs. In my original draft, the sentence in question ended: “…a description of objective reality rather than mere linguistic convention or the like.” Those last three words were intended to indicate that convention is not the only thing an anti-realist might regard as the ground of mathematical truth. (And I had already made it clear earlier in the review that anti-realism comes in many versions.)

Unfortunately, the copy editor apparently thought those three words otiose and removed them, and, again, I failed to notice the change when reviewing the proofs. (I’m not blaming the copy editor, but myself. These things happen, and copy editors have saved me from many infelicities over the years!)

Anyway, as I say, the rest of the review makes it clear that it is the threat of voluntarism that is the problem. I also point out that there are two serious lacunae in Bill’s discussion: first, too superficial a treatment of the Aristotelian realist approach to mathematics; and, second, a failure to consider how absolutely central the doctrine of divine simplicity is to the way the classical theist tradition understands both divine aseity and divine conceptualism.

These three issues – voluntarism, Aristotelian realism, and divine simplicity – are the ones my critique of Bill’s position hinges on. It has nothing to do with conventionalism.

By the way, as I hope my review also made clear, none of this should keep anyone from reading Bill’s book. On the contrary, anyone interested in these issues ought to read it. You will always profit from reading and engaging with Bill’s work, even when you end up disagreeing with him.

Published on March 28, 2020 12:07

March 24, 2020

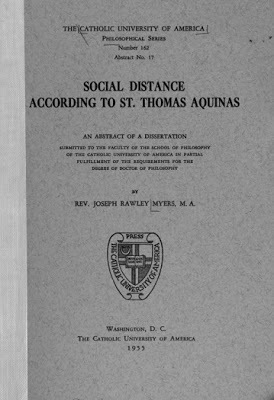

Aquinas anticipated everything

So notes a friend who sent me this image of the cover of a dissertation from the 1950s. (No doubt the author was using the phrase in a different sense than has now become familiar. Any guesses as to the true subject matter?)

UPDATE: Dave Lull sends the following:

From page 1:

“Social distance may be thought of either as an attitude of mind or as those acts flowing from this mental state. An attitude of social distance is an erroneous bias unreasonably held by the individuals of one group against another group. Acts of social distance are unjust differential treatment of individuals considered to belong to a particular group. It will be the task of the following section on the psychology of social distance to explain these definitions according to Thomistic philosophy.

“Prejudice is a broader term than social distance. It is the genus of which social distance is a species. For that reason much of what is said of prejudice or prejudicial attitudes pertains to social distance. Prejudice may be defined as an attitude of mind towards persons or things producing a bias in favor of, or adverse to, such persons or things and a judgment on them before adequate knowledge of the facts has been obtained.”

See also the explanation from Brandon in the comments below.

Published on March 24, 2020 09:46

March 20, 2020

Craig contra the truthmaker objection to presentism

Presentism holds that, in the temporal realm (that is to say, apart from eternal and aeviternal entities), only present objects and events exist. Now, if statements about past events and objects are true, then there must be something that makes them true. But in that case, the “truthmaker objection” to presentism holds, past objects and events must exist. I’ve argued in previous posts that this objection is greatly overrated. Indeed, for the reasons I gave there, I can’t myself fathom what all the fuss is about. William Lane Craig seems to agree. In his book

God Over All

(which I reviewed recently in First Things), he has occasion briefly to address the issue. Craig writes:[I]t seems indisputably true that ‘There have been forty-four US presidents’. The non-existence of most of them is no impediment to our quantifying over past US presidents. To infer from the truth of such statements that time is, in fact, tenseless and that past and future individuals are on an ontological par with present individuals would be to draw a breathtaking metaphysical inference on the basis of the slim reed of the neo-Quinean criterion of ontological commitment.

Presentism holds that, in the temporal realm (that is to say, apart from eternal and aeviternal entities), only present objects and events exist. Now, if statements about past events and objects are true, then there must be something that makes them true. But in that case, the “truthmaker objection” to presentism holds, past objects and events must exist. I’ve argued in previous posts that this objection is greatly overrated. Indeed, for the reasons I gave there, I can’t myself fathom what all the fuss is about. William Lane Craig seems to agree. In his book

God Over All

(which I reviewed recently in First Things), he has occasion briefly to address the issue. Craig writes:[I]t seems indisputably true that ‘There have been forty-four US presidents’. The non-existence of most of them is no impediment to our quantifying over past US presidents. To infer from the truth of such statements that time is, in fact, tenseless and that past and future individuals are on an ontological par with present individuals would be to draw a breathtaking metaphysical inference on the basis of the slim reed of the neo-Quinean criterion of ontological commitment.

It is noteworthy that in debates over presentism, tenseless time theorists tend simply to presuppose without argument that quantification is ontologically committing, and so our ability to quantify over past/future individuals in true sentences is taken to commit us to their existence… It never seems to occur to tenseless time theorists that our ability to quantify over purely past/future individuals in true sentences might be a good reason to reject the criterion of ontological commitment which they unquestioningly presuppose… [I]t is far more obvious that, for example, the [past-tensed] statement ‘Some medieval theologians wrote in Latin’ is true than that the neo-Quinean criterion of ontological commitment is true. (pp. 117-18)

End quote. Here Craig frames the issue in terms of “ontological commitment” rather than “truthmaking,” but in this context the basic issue is the same. The writers he is responding to hold that if we take statements about past objects and events to be true, then we are thereby “ontologically committed” to the existence of past objects and events. Similarly, the truthmaker objection holds that if we take statements about past objects and events to be true, then we are thereby committed to the existence of past objects and events as “truthmakers” of those statements.

The last sentence in the passage quoted from Craig is directed at philosophers who suggest that presentists, to be consistent, should give up the assumption that past-tensed statements are true, in favor of a “fictionalist” thesis that we should regard such statements merely as if they were true. As Craig rightly says, what should be given up instead are the tendentious metaphysical assumptions that inspire such bizarre proposals! In fact it is perfectly possible consistently to take statements about past objects and events to be true while at the same time denying that past objects and events exist. As Craig says, it isn’t the truth of these statements that entails otherwise, but rather the neo-Quinean assumptions that are read into the statements that entail otherwise.

That has been my point in my earlier remarks about the truthmaker objection. I am happy to agree with the claim that true statements require truthmakers. Indeed, it’s just common sense, and the truthmaker objection trades on the commonsense appeal of the claim. But by itself the claim is in fact not terribly informative, because “truthmaking” is a vague notion. Take the statements “Robert Downey, Jr. is an actor” and “Tony Stark is Iron Man.” Both statements are true, and both have truthmakers. But the respective truthmakers are very different. The first statement is true because Robert Downey, Jr. really exists and really is an actor. The second statement is true because the Marvel comics and movies were written a certain way, but not because Tony Stark exists, since he doesn’t.

If you wanted to justify some dramatic metaphysical conclusion to the effect that fictional characters like Tony Stark exist, you aren’t going to get it from the (trivial) fact that true statements require “truthmakers.” Rather, you’re going to have to come up with some metaphysical theory that restricts what can count as a “truthmaker,” and then justify reading this theory into the commonsense (and indeed by itself pretty banal) thesis that true statements require truthmakers. Trying to pull the dramatic metaphysical conclusion out of the banal commonsense premise that truths require truthmakers is just sleight of hand.

Craig makes the same point about all the heavy-going talk among analytic philosophers about “ontological commitment.” Common sense would agree that when we make a true statement, the things that the statement is about in some sense “exist.” But terms like “exist” are in ordinary usage very elastic, covering not only tables, chairs, and the like, but things as diverse as the way that you smile, a lack of compassion in the world, the chance that something will not happen, the way things might have been, and so on (to cite several examples of the sort Craig gives on pp. 111-12). And there is nothing in common sense that entails that the way things might have been is an entity in the way that a table is an entity. You can arguethat it is, on the basis of some metaphysical theory, but it would in that case be the theory – and not common sense – that is doing the work.

Commonsense usage, Craig says, is “metaphysically lightweight” (p. 112). The neo-Quinean metaphysician reads his heavyweight metaphysics into ordinary usage and pretends that he is simply drawing out the implications of common sense.

I have argued that the truthmaker objection to presentism does exactly the same thing. “Caesar was assassinated on the Ides of March” is true, and common sense would agree that this truth needs a truthmaker. And it has one. Caesar’s really having been assassinated on the Ides of March (rather than this being a fictional story, say) is what makes the statement true.

Now, the proponent of the truthmaker objection comes along and says that this entails that Caesar, his assassination, etc. exist, no less than present objects and events do. But this doesn’t follow from common sense. Rather, it follows only from some metaphysical theory about what can count as a “truthmaker.” Hence for anyone who does not accept that theory – as, of course, presentists would not – the objection amounts to just a question-begging assertion. It seems more than that only if we read the metaphysical theory into the commonsense and banal “truthmaking” assumption shared by presentist and non-presentist alike.

I noted in an earlier post on this subject that we have ample independent reason to reject the anti-presentist’s assumptions about “truthmaking.” Consider “negative existentials” like the statement “There are no unicorns.” This statement is true, and thus needs a truthmaker. But it can’t be that there is some entitythat makes it true, since the statement is denyingthe reality of some entity rather than affirming it. So what is it that makes the statement true? Common sense would say: “The fact that there are no unicorns, the absence of unicorns from reality, is what makes it true. What’s the big deal?” Some metaphysicians respond: “But then what is a fact? What is an absence? Aren’t these entities of some kind?”

Now, you might think this a major metaphysical conundrum. Or, stifling a yawn, you might think it much ado about nothing. Either way, it certainly doesn’t entail that people who deny the existence of unicorns need to go into crisis mode, and to reject or at least remain agnostic about the statement “There are no unicorns” until the metaphysicians have solved the alleged problem. If anything, it is the metaphysicians who need to conform their theorizing to the truth of the statement “There are no unicorns.” It isn’t those who affirm this obvious truth who need to conform their opinions to some tendentious metaphysics.

Similarly, if the proponent of the “truthmaker objection” thinks it a real chin-puller to understand how statements about past objects and events can be true if past objects and events don’t exist, he is welcome to pull his chin. It’s a free country. But he can’t reasonably expect the rest of us to agree that this a deep metaphysical problem for presentism, any more than there is a deep metaphysical problem for people who affirm that there are no unicorns. Or at least, he can’t expect us to think that the banal thesis that truths require truthmakers shows that there is any deep metaphysical problem. He’s first got to justify his tendentious metaphysical assumptions about what can count as truthmaking if he’s going to convince us that we need to pull our chins too.

Craig offers several important further parallel examples. There is, first of all (pp. 113-17), the case of quantification into intentional contexts, which is standardly taken to involve quantification into intensional contexts. (Note the difference here between intentionality-with-a-tand intensionality-with-an-s, which are related but distinct technical notions.) Take the statement “Ponce de Leon was searching for the Fountain of Youth.” This is an “intentional” context (to use the jargon of philosophy of mind) in the sense that it concerns the contents of a person’s thoughts, which have the feature of intentionality or “aboutness.” Ponce de Leon’s thought was about the Fountain of Youth. It is said also to be an “intensional” context (to use the jargon of logic and philosophy of language) insofar as we cannot quantify into it, i.e. affirm the existence of all the things its terms refer to. Though the statement is true, there is no Fountain of Youth.

Now, as Craig points out, the statement in question nevertheless seems obviously to entail the further statement “There is something that Ponce de Leon was searching for.” After all, Ponce de Leon was not wandering around aimlessly. There was a specific thing he was trying to find. But it might seem problematic to affirm this further statement, insofar as it might seem to entail the existence of the thing (namely the Fountain of Youth) that Ponce de Leon was looking for. But this would follow, Craig says, only if we assume a neo-Quinean criterion of ontological commitment, on which the use of quantificational phrases like “There is” necessarily commits the user to the existence of something. The “problem” disappears if we don’t make this assumption. It arises only given a tendentious metaphysical interpretation of ordinary usage, not from ordinary usage itself.

Another example would be modal contexts, such as statements about possibilities (pp. 119-21). Consider that there are uncountably many stars that could have existed even if they don’t. Hence the statement “There are uncountably many possible stars” is true. Should we conclude that these possible stars must really exist after all? Some metaphysicians would draw precisely such conclusions. Now, like me and like Craig, you might think this an utterly ridiculous non-starter. Or, instead, you might think that the question whether such a result follows is, however bizarre, another real chin-puller that we need to take seriously. Either way, as Craig notes, the truth of the statement “There are uncountably many possible stars” by itself does not entail any such recherché metaphysics. You have to read the metaphysics intothe statement before you can read it out again.

Or consider mereological statements, i.e. those concerning parts and wholes (pp. 121-24). For example, consider a statement like “There is an entity consisting of my left hand and the coffee cup sitting next to it.” We can come up with innumerably many such statements about all kinds of similarly bizarre objects (or “mereological fusions,” as philosophers like to call them) – the object consisting of your eyeglasses, the moon, and a certain ham sandwich; the object consisting of the center of the earth, the square root of 2, and the temperature in Phoenix; and so on.

We can talk about these entities and (to go along with the gag for the sake of argument) even make true statements about them. So should we conclude that the object consisting of my left hand and the coffee cup sitting next to it is a real entity on all fours with you and the table you are sitting at? Does this follow from the truth of the statement?

You might think this is really serious, cutting-edge metaphysics. Or you might think it is too stupid for words. Either way, Craig’s point is that affirming statements like the one in question does not by itself commit you to the existence of such bizarre entities. It can do so only if conjoined with some tendentious metaphysical theory, such as a neo-Quinean criterion of ontological commitment, or some metaphysically loaded “truthmaker theory.”

Now, I would say that what we have in these various cases is essentially just a set of logico-linguistic puzzles. They are not without interest, and ultimately they may even have metaphysical implications of some sort or other. What they do not do is by themselves have any obvious metaphysical implications, and they certainly do not by themselvespose any grave challenge to any commonsense metaphysical assumption.

The same thing is true of the puzzle raised by the “truthmaker objection” to presentism. By itself it doesn’t raise a metaphysical problem that is any more grave or pressing or dramatic than these other puzzles. It’s a logico-linguistic puzzle alongside other logico-linguistic puzzles, that’s all. To ask:

“How can statements about the past be true if past objects and events don’t exist?”

is like asking:

“How can statements about fictional characters be true if fictional characters don’t exist?”

or:

“How can negative existential statements be true if the things they talk about don’t exist?”

or:

“How can statements about what people believe in, desire, search for, etc. be true when the things they believe in, desire, search for, etc. don’t exist?”

or:

“How can statements about merely possible things be true when those things don’t exist?”

or:

“How can a statement about the object consisting of my left hand and a coffee cup be true if that object doesn’t seem to have the kind of reality that a table does?”

You can puzzle over these things if you like, and it can be worthwhile doing so as long as one keeps in mind the precise nature and scope of the inquiry. But in my opinion, to suppose that the first of these questions poses a grave threat to presentism is ridiculous. It is like supposing that these other questions entail that there is grave pressure on us to believe in the existence of fictional characters, non-existent things, every single object of belief or desire, merely possible objects, all mereological fusions, etc.

Craig alludes to the assumption, made by many philosophers who write on these topics, that “exists” is a univocal term, though he does not pursue the issue. But in my view, that is a major part of the problem, and one that any Scholastic is bound to be sensitive to. “Exists” and related terms are analogicalrather than either univocal or equivocal, and we are bound to be led into trouble when we ignore this. There are also the Scholastic distinctions between real being, beings of reason, intentional being, and (for some Scholastics) an intermediate category between real beings and beings of reason. Too much contemporary discussion of the issues rides roughshod over such distinctions, wrongly treating terms like “exist” as if they have the same force in all contexts.

Published on March 20, 2020 15:08

March 15, 2020

Coronavirus complications

For reasons most of which have to do directly or indirectly with the COVID-19 coronavirus situation, none of the remaining public lectures for the first half or so of the year that I had announced a couple of months ago will occur. (There are still events planned for the latter half of the year, which I will announce closer to the time.)

For reasons most of which have to do directly or indirectly with the COVID-19 coronavirus situation, none of the remaining public lectures for the first half or so of the year that I had announced a couple of months ago will occur. (There are still events planned for the latter half of the year, which I will announce closer to the time.)Also, in light of the situation, my college, like many others, has abruptly transitioned to online teaching. The resulting new workload promises to be as heavy as it was sudden and unexpected.

I fully intend to keep this blog going to doomsday and beyond, but if things temporarily get a little slower here in the next couple of weeks as I adjust to this new reality, that is why!

Published on March 15, 2020 11:22

March 11, 2020

Review of Craig’s God Over All

My review of William Lane Craig’s book

God Over All: Divine Aseity and the Challenge of Platonism

appears in the April 2020 issue of First Things. You can read it online here.

My review of William Lane Craig’s book

God Over All: Divine Aseity and the Challenge of Platonism

appears in the April 2020 issue of First Things. You can read it online here.

Published on March 11, 2020 21:23

March 8, 2020

On-topic open thread (and a word on trolls)

Folks, please don’t post off-topic comments in the comboxes. I will delete them, and any responses to them, as soon as I see them, and (since I don’t always see them immediately) sometimes that means that a long thread will develop that is destined to end up in the ether. Remember, if your comment begins with something like “This is off topic, but…,” then it isn’t a comment you should be posting. And remember too, there is always that remedy for concupiscence known as the open thread. Here’s the latest. This time, everything is on topic, from acid jazz to Thomas Szasz, from Family Guy to Strong AI, from the coronavirus to Miley Cyrus. While I’ve got your attention, a word on trolling. It’s a continual problem, and sometimes bigger than it needs to be because of people who keep feeding trolls. Occasionally I have to ban people outright, but as you know, I prefer not to do that. A handful of trolls over the years have been so insufferable and psychotic that they simply have to be cast forever into that outer darkness where there is wailing and gnashing of teeth. The marks of such unforgiveable trolls include: a monomania that insists on bringing every discussion around to some irrelevant pet obsession; repeatedly posting the same comment over and over no matter how many times it is deleted; flooding the combox with comments throughout the day or the week; an unwillingness or inability to restrain a penchant for rudeness, obscenity, blasphemy, or personal animus against the host of the blog; and other behavior that normal human beings know to avoid.

Folks, please don’t post off-topic comments in the comboxes. I will delete them, and any responses to them, as soon as I see them, and (since I don’t always see them immediately) sometimes that means that a long thread will develop that is destined to end up in the ether. Remember, if your comment begins with something like “This is off topic, but…,” then it isn’t a comment you should be posting. And remember too, there is always that remedy for concupiscence known as the open thread. Here’s the latest. This time, everything is on topic, from acid jazz to Thomas Szasz, from Family Guy to Strong AI, from the coronavirus to Miley Cyrus. While I’ve got your attention, a word on trolling. It’s a continual problem, and sometimes bigger than it needs to be because of people who keep feeding trolls. Occasionally I have to ban people outright, but as you know, I prefer not to do that. A handful of trolls over the years have been so insufferable and psychotic that they simply have to be cast forever into that outer darkness where there is wailing and gnashing of teeth. The marks of such unforgiveable trolls include: a monomania that insists on bringing every discussion around to some irrelevant pet obsession; repeatedly posting the same comment over and over no matter how many times it is deleted; flooding the combox with comments throughout the day or the week; an unwillingness or inability to restrain a penchant for rudeness, obscenity, blasphemy, or personal animus against the host of the blog; and other behavior that normal human beings know to avoid. But there are other, less extreme trolls whose sins are more minor or who show a willingness to reform. Marks of this milder kind of troll would be: monomania, rudeness, logorrhea, etc. that manifest only occasionally; irremediable ignorance or muddleheadedness that makes a commenter tiresome and not worth engaging, but that is not manifested in a rude or otherwise obnoxious way; a predilection for comments that are not quite off-topic but are nevertheless banal, ill-informed, weird, or otherwise not substantive; and so on. Most of these people I simply tolerate. There are also some who I have had to ban temporarily, but whose return to the comboxes I have tolerated when they have given signs of a willingness to restrain their more obnoxious tendencies.

I leave it to you, reasonable reader, to use good judgment in dealing with such people. If someone seems to be a crank or otherwise not worth engaging with, then don’t engage with him. He may have nothing better to do, but surely you do. And you will be doing a great service to me and to your fellow readers. Sometimes what starts out to be merely a stupid comment or two that can be left to stand in the spirit of tolerance, turns into a long, pointless, acrimonious thread-killing exchange, all because one or two otherwise reasonable readers wouldn’t resist the urge to feed the troll. Sometimes I delete this garbage in the hope of saving the thread, but other times, by the time I see it, it is too late. And in any event, I’m too busy with other things to monitor this stuff hour by hour.

Do your part! Don’t feed trolls! Now, on with the open thread. Previous open threads archived here.

Published on March 08, 2020 15:58

March 3, 2020

The other way to lose a war

Rod Dreher commentson the U.S. deal with the Taliban to withdraw, at long last, from Afghanistan. He writes: “The Taliban whipped… the United States… We simply could not prevail. The richest and most powerful nation in the world could not beat these SOBs.” Well, that’s obviously not true in the usual sense of words like “whipped” and “beat.” Suppose you effortlessly beat me to a bloody pulp and I fall to the ground, desperately panting for air and barely conscious. You put your boot on my neck and demand that I cry “Uncle.” I refuse, despite your repeated kicks to the gut, and after fifteen minutes or so of this you get bored and walk away. It would be quite absurd if, wiping the blood off my face and pulling myself up to my wobbling knees, I proudly exclaim: “Did you see how I whipped that guy?” But of course, I know what Dreher means, and he’s not wrong. One way to lose a war is militarily. The U.S. did not lose the war in Afghanistan in that sense. Indeed, it’s very hard for the U.S. to lose wars in that sense. The other way to lose a war, however, is to define “victory” in so ambitious – and ultimately non-military – a way that military success becomes irrelevant. If you establish before our fistfight begins that you will only count yourself to have defeated me if you get me to say the word “Uncle,” then as long as I refuse to do that, you will have lost, no matter how badly you beat me up and indeed even if you kill me.

Rod Dreher commentson the U.S. deal with the Taliban to withdraw, at long last, from Afghanistan. He writes: “The Taliban whipped… the United States… We simply could not prevail. The richest and most powerful nation in the world could not beat these SOBs.” Well, that’s obviously not true in the usual sense of words like “whipped” and “beat.” Suppose you effortlessly beat me to a bloody pulp and I fall to the ground, desperately panting for air and barely conscious. You put your boot on my neck and demand that I cry “Uncle.” I refuse, despite your repeated kicks to the gut, and after fifteen minutes or so of this you get bored and walk away. It would be quite absurd if, wiping the blood off my face and pulling myself up to my wobbling knees, I proudly exclaim: “Did you see how I whipped that guy?” But of course, I know what Dreher means, and he’s not wrong. One way to lose a war is militarily. The U.S. did not lose the war in Afghanistan in that sense. Indeed, it’s very hard for the U.S. to lose wars in that sense. The other way to lose a war, however, is to define “victory” in so ambitious – and ultimately non-military – a way that military success becomes irrelevant. If you establish before our fistfight begins that you will only count yourself to have defeated me if you get me to say the word “Uncle,” then as long as I refuse to do that, you will have lost, no matter how badly you beat me up and indeed even if you kill me.The trouble with the recent wars in Afghanistan and Iraq is that “victory” was widely conceived of on the World War II model – unconditional surrender followed by the radical reconstruction of the enemy’s social, political, and economic orders along the victor’s preferred lines. Elizabeth Anscombe famously argued (in her essay “Mr. Truman’s Degree”) that that was not a reasonable standard even in the case of World War II. It was certainly not a reasonable standard in the Afghanistan and Iraq wars. Those should have been conceived of from the start as punitive strikes rather than Wilsonian crusades. Replacing the wicked leaders of these countries was justifiable in principle, but the goal should have been “something less bad” rather than an approximation of American capitalist liberal democracy.

Some critics like to chalk up prolonged American engagement in places like Afghanistan and Iraq to warmongering or realpolitik or some other sinister motivation. In my opinion, that is the reverse of the truth. The fault of those who advocate such engagement isn’t worldly cynicism, but otherworldly idealism.

Here we might draw a comparison with the problem Anscombe was addressing. She rightly condemned as intrinsically evil the World War II policy of massacring civilian populations so as to compel enemy governments to capitulate. But she also laid the blame for this policy at the feet of an attitude that is also evil, but is widely regarded as good: pacifism. The pacifist foolishly condemns all killing as such, and therefore all war as unjust. This is an error, and a grave one because it is utterly impracticable, and trying to implement it would lead to the widespread oppression and killing of the innocent.

When pacifism is widely admired, however, those who nevertheless reject it as impracticable conclude that doing what is goodis impracticable and that it is practically unavoidable to do evil. That is to say, they conclude that all killing is wrong but that we nevertheless have to do this sort of wrong in order to resist oppressors and killers. And then the sky is the limit. Such people will go on to conclude that if killing enormous numbers of innocent people is necessary in order to realize some aim they judge to be good (such as securing the unconditional surrender of the enemy) then this is what should be done. Hence Dresden, Hiroshima, Nagasaki, etc.

In Anscombe’s view, then, pacifism thereby leads to morerather than less killing of the innocent. It is held up as a noble ideal when in fact it is simply a grave moral error that has obscene unintended consequences. The correct attitude is to recognize the natural law principle that it is only the intentional killing of the innocent, rather than all killing as such, that is morally wrong, and then to formulate principles to guide us in determining the conditions under which the killing of evildoers is called for, the means by which this might legitimately be done, the circumstances when risk of unintended civilian deaths can be justified by double effect, and so forth. That is what traditional just war theory does.

Now, what I want to suggest is that there is an analogous error in too much modern American thinking about matters of war. The idea seems to be that war is such an obscenity that only a grandiose end can justify it. On this view, merely repelling an aggressor or deterring his future evildoing is not good enough. The endgame must always involve tyrants being overthrown, oppression banished, happy voters standing in queue, children dancing in the streets, etc. Hence, when we see that some particular war is indeed necessary, the tendency is to try to turn it into a World War II style liberation and reconstruction.

Part of the problem with this is that realizing a grandiose end tends to require far more killing than is necessary for a more limited aim – and the more unrealistic and therefore unattainable the grandiose end is, the more ultimately pointless is the killing. Another problem is that even a crushing military victory comes to seem ultimately like a defeat as long as the grandiose end remains unrealized. Hence military engagement becomes interminable. “If we leave before the job is done [i.e. the enemy’s country looks more like an American-style democracy and market economy] it will all have been for nothing!”

The pacifist would outlaw all war, whereas the Wilsonian would pursue “war to end all wars.” The first is utopian about means, the second is utopian about ends. And both only end up making wars more common and longer and bloodier than they need to be.

Published on March 03, 2020 19:14

February 27, 2020

Agere sequitur esse and the First Way

Aquinas’s First Way is also known as the argument from motion to an Unmoved Mover. The most natural way to read it is as an argument to the effect that things could not change at any given moment if there were no divine cause keeping the change going. But some Thomists have read it instead as an argument to the effect that changing things could not even exist at any given moment if there were no divine cause keeping them in being. That’s the reading I propose in my book

Aquinas

and my ACPQ article “Existential Inertia and the Five Ways,” and it’s a line of argument I develop and defend in greater depth in chapter 1 of

Five Proofs of the Existence of God

. On my way of presenting the argument, it begins with change, not because this is the phenomenon the argument is ultimately most concerned to explain, but rather because it provides the clearest way to introduce the distinction between actuality and potentiality. Change entails the actualization of potential, but so too does the sheer existence of a thing at any moment. The latter is what the argument, as I present it, is ultimately most concerned with. But it is much easier for most readers to get an initial handle on the concept of the actualization of potential by considering change than it is by considering the existence of a thing at a moment.

Aquinas’s First Way is also known as the argument from motion to an Unmoved Mover. The most natural way to read it is as an argument to the effect that things could not change at any given moment if there were no divine cause keeping the change going. But some Thomists have read it instead as an argument to the effect that changing things could not even exist at any given moment if there were no divine cause keeping them in being. That’s the reading I propose in my book

Aquinas

and my ACPQ article “Existential Inertia and the Five Ways,” and it’s a line of argument I develop and defend in greater depth in chapter 1 of

Five Proofs of the Existence of God

. On my way of presenting the argument, it begins with change, not because this is the phenomenon the argument is ultimately most concerned to explain, but rather because it provides the clearest way to introduce the distinction between actuality and potentiality. Change entails the actualization of potential, but so too does the sheer existence of a thing at any moment. The latter is what the argument, as I present it, is ultimately most concerned with. But it is much easier for most readers to get an initial handle on the concept of the actualization of potential by considering change than it is by considering the existence of a thing at a moment. Now, does that mean that at the end of the day, a divine cause really explains at most only the existence of a thing at a time, and that this cause does not after all explain change? Should we say that God merely keeps things in existence but that, for all Aquinas can show, their changes require no divine explanation?

No, that doesn’t follow, and it isn’t true. Recall the principle agere sequitur esse or “action follows being,” which I defend and deploy in Five Proofs (and which I’ve had occasion to discuss in a recent post and in various earlier posts). As I’ve argued there and elsewhere, the principle, together with other considerations raised by arguments like the argument from motion, entails a concurrentist account of God’s relationship to the world. Given that action follows being – that the way a thing operates reflects its mode of existing – we can conclude that a thing would have no causal efficacy at all without God’s cooperation or concurrence with its activity, just as a pen could not write without your cooperation or concurrence with it (by holding and moving it). For if a thing could act or operate apart from God’s action, then since the way a thing acts reflects its mode of being, it could also exist apart from God’s action. And that is ruled out by arguments like the argument from motion, developed the way I develop it. (See Five Proofs for the details of this defense of concurrentism.)

Since change always involves a potential being actualized by some efficient cause, change too, and not merely the existence of things, thus requires a divine cause (to cooperate or concur with the efficient cause). The overall picture is therefore much like that of what I characterized above as the first and more natural reading of the First Way. But the line of argumentation is less direct. It isn’t a straight shot from the reality of change to the conclusion that the Unmoved Mover must keep change going. It’s rather an argument from the sheer existence of things to the conclusion that the Unmoved Mover must keep them in existence, and then a combination of this result with the principle agere sequitur esse to yield the further result that the activity of things, and thus their bringing about of change, requires divine concurrence.

That’s not to say that the more direct sort of argument is not correct. It’s just that that’s not the sort of argument I’ve been the most interested in defending.

Here’s another observation. Aristotle’s own version of the argument from motion to an Unmoved Mover is often interpreted as an explanation precisely of change rather than the existence of things. The idea (on this interpretation) is that Aristotle thinks an Unmoved Mover is necessary in order to account for why the world continues to change from moment to moment, but he does not take the sheer beingof the world from moment to moment to require such an explanation. (I put to one side the question of whether this is a correct interpretation of Aristotle.)

The principle agere sequitur esse would arguably afford a path even from this version of the Unmoved Mover argument to the conclusion of the version I defend. If action follows being, then if change – and thus the action of things in the world – requires an explanation in terms of a divine cause, then the sheer being of things must require such an explanation too. For if things could exist apart from such a cause, why couldn’t they act apart from it?

If this is correct, then the three dimensions of our discussion – the being of a thing, the action of a thing, and the link between being and action enshrined in the principle agere sequitur esse – are thus so tightly interconnected that the differences between interpretations of the argument from motion may be moot. We can reason from the being of things to the existence of an Unmoved Mover, and the principle agere sequitur esse will then tell us that the action of those things too requires the Unmoved Mover. Or we can reason from the action of things to the existence of an Unmoved Mover, and the principle agere sequitur esse will then tell us that the being of those things too requires the Unmoved Mover. We end up at the same place, by neighboring routes.

Related posts:

A first without a second

Final causality and Aristotle’s Unmoved Mover

Prior on the Unmoved Mover

Four causes and Five Ways

Oerter on motion and the First Mover

Dharmakīrti and Maimonides on divine action

Published on February 27, 2020 18:41

February 21, 2020

Morgan on Aristotle’s Revenge

At The Imaginative Conservative, Prof. Jason Morgan kindly reviews my book

Aristotle’s Revenge

. From the review:

At The Imaginative Conservative, Prof. Jason Morgan kindly reviews my book

Aristotle’s Revenge

. From the review:In 456 very well-written pages… (followed by a treasure trove of a bibliography), Dr. Feser shows in Aristotle’s Revenge that, point for point, Aristotle got science right, or as right as he could given the limitations in instrumentation and communication with other researchers during his time. Scientists since the so-called Enlightenment have been trying to detach Aristotle’s greatest insight, the telos of things, from the world around them. But the telos is the linchpin of the material world, so without it, everything, as is apparent from most philosophy lectures one attends nowadays, or nearly any philosophy book one reads, falls apart… [T]he most compelling part of Aristotle’s Revenge is section six, “Animate Nature.” Here, Dr. Feser goes a very long way toward restoring the life sciences to their proper relation to purpose and cause…

[O]ne of the greatest services of Aristotle’s Revenge, and of Dr. Feser’s work in general, is the clarity that Dr. Feser brings to discussions about terms and concepts.

End quote. Morgan gives special attention to the criticisms of Intelligent Design theory that I raise in that chapter.

Morgan also offers a suggestion for improvement:

I think that Dr. Feser’s call for a return to a teleological view of the cosmos could be even stronger with a more clearly-defined deployment of, for example, the term “species.” Dr. Feser goes to great lengths in part six of Aristotle’s Revenge to distinguish among various uses of the term, setting, for example, “logical species” off from the very different (but often conflated, to disastrous effect) “philosophical species.” This is helpful and correct, but I would suggest that Dr. Feser’s readers seek out the works of Peter Redpath, John Deely, and Charles Bonaventure Crowley for even deeper insights into the work that genus and species – not the terms, but the Aristotelian-Thomistic realities – really do.

Fair enough. Aristotle’s Revenge interacts with an enormous body of literature, but so vast is the subject matter that there is much more I could have covered. I thank Prof. Morgan for his suggestions and for his review.

Published on February 21, 2020 17:53

February 15, 2020

The socialist state as an occasionalist god

Hobbes famously characterized his Leviathan state as a mortal god. Here’s another theological analogy, or set of analogies, which might illuminate the differences between kinds of political and economic orders – and in particular, the differences between socialism, libertarianism, and the middle ground natural law understanding of the state.

Hobbes famously characterized his Leviathan state as a mortal god. Here’s another theological analogy, or set of analogies, which might illuminate the differences between kinds of political and economic orders – and in particular, the differences between socialism, libertarianism, and the middle ground natural law understanding of the state.Recall that there are three general accounts of divine causality vis-à-vis the created order: occasionalism, mere conservationism, and concurrentism (to borrow Fred Freddoso’s classification). Occasionalism holds that God alone has causal efficacy, and the apparent causal power of created things is illusory. It seems to us that the sun causes the ice in your lemonade to melt, but it is really God causing it to melt, on the occasion when the sun is out. It seems that it is the cue ball that knocks the eight ball into the corner pocket, but it is really God who does so, on the occasion when the cue ball makes contact with it. And so on. Created things no more act than puppets do. Just as it is really the puppeteer who moves the puppet around the stage by means of its strings, with the puppet doing nothing, so too it is God who brings about every effect in the world. Indeed, created things are more like shadow puppets than the kind moved about by strings. The latter sort of puppet might have at least an indirect causal efficacy by virtue of accidentally knocking into other things, but a shadow puppet cannot do even that much. And neither can any created thing, according to occasionalism.

Mere conservationism, by contrast, holds that created things not only have causal power, but exercise it completely independently of God. God merely conserves them in existence as they do so, while playing no role in their efficacy. Though God keeps the sun in existence, it is the sun and the sun alone that causes your ice to melt. Though God keeps the cue ball in existence, it is the cue ball and the cue ball alone that causes the eight ball to move. And so on.

Concurrentism is a middle ground position. It holds, contra mere conservationism, that God not only conserves things in existence, but also must concur or cooperate with their activity if they are to have any efficacy. But it also holds, contra occasionalism, that created things do have real efficacy, even if not on their own. To borrow an example from Freddoso, when you use a piece of blue chalk to write on the chalkboard, the chalk would be unable to have this effect if you were not moving it. Left to itself, it would simply lie there. All the same, its nature makes a real contribution to the effect insofar as the letters would not be blue if the piece of chalk were not itself blue. Or consider a battery-powered toy car. The motor really does move the wheels of the car and thus the car itself, but would not be able to do so if not for the battery that powers it. God is like you in Freddoso’s example or like the battery in mine. He must concur or cooperate with the cause if it is to have its effect, but the cause nevertheless makes a real contribution of its own.

One reason to prefer concurrentism to these alternatives derives from the Scholastic principle agere sequitur esse or “action follows being.” On this principle, what a thing does reflects what it is. If created things don’t really do anything, as occasionalism holds, then it seems they have no reality at all. God alone is real, and when we observe what we take to be created things in action, what we are really observing is God in action. Occasionalism thus collapses into pantheism. Hence if pantheism is false, so too occasionalism must be false.

If, by contrast, created things can act entirely apart from God, then it seems (given that action follows being) that they can exist entirely apart from God. Divine conservation would go out the window with divine concurrence. Mere conservationism thus collapses into atheism, so that if atheism is false, so too mere conservationism must be false.

Concurrentism would thus stand as the only way rightly to understand the relationship between God and the world given that agere sequitur esse. The world has real causal efficacy of its own because its existence is really distinct from God’s, but it nevertheless requires God to concur in its causal activity just as it requires God to conserve it in existence. (For more on all of this, see Five Proofs of the Existence of God , especially pp. 232-46.)

Now, what does all this have to do with the varieties of political order? Again, I would propose that there is an analogy here with the relationship between socialism, libertarianism, and the traditional natural law understanding of the state. In a lecture on socialism and the family that I gave about a year ago, I noted that socialism involves centralized governmental ownership of the basic means of production and distribution, and that the ownership of a thing, in turn, entails having a bundle of rights over it. Hence, the more rights a government claims over the basic economic means of a society, the more it claims de facto ownership over them, and the closer it approximates to a socialist system. Socialism can come in degrees. (Listen to the lecture for qualifications and details.)

That is a point about the economic aspect of socialism, but as I noted in the same lecture, there is also an ethos or moral vision associated with it. In particular, it is a collectivist ethos according to which the basic economic means are owned and utilized by government for the sake of society as a whole, rather than for the sake of any individual or group within society. One could develop this ethos further in at least two ways. One could take society to be a kind of organism of which individual citizens are like mere dispensable cells or organs, to be sacrificed for the good of the whole if necessary in the way that an organ or cells can be shed for the sake of the preservation of the body. Totalitarian forms of socialism approximate this extreme form of collectivism. Alternatively, one could take all individual citizens to have inherent and equal value, and therefore not to be sacrificed for the good of the whole even if they are expected to work for the good of the whole. Egalitarian forms of socialism would correspond to this less extreme form of collectivism.

Now, when you use something that I own and you use it only in the ways that I direct you to use it, I can be said to be acting through you. You function merely as my agent. Your acts are really my acts insofar as you serve as a kind of extension of myself. For example, a lawyer or employee might function this way. Similarly, the more rights a socialist state would claim over both the resources that its citizens use and over decisions about the ways that they may use them, and the more such a state regards citizens as mere organs or cells of the social whole, the more fully it can be said to treat citizens merely as extensions of itself.

Here, I would suggest, we have something analogous to occasionalism, with the socialist state serving as a rough analogue to the occasionalist understanding of God and individual citizens roughly analogous to created things as conceived of on occasionalism. The more fully the citizens have to follow the directives of the state, the more akin they are to the inefficacious physical objects of occasionalism – mere puppets of which the state is the puppeteer. It is really the state that acts through them, just as for the occasionalist it is really God rather than the sun making the ice melt. And a totalitarian socialist state that treats society as a whole as if it were the only real substance, with individual citizens merely its cells, is analogous to an occasionalism that has collapsed into pantheism. Only society really exists, with the citizens being its appendages, just as on pantheism only God really exists and the things and events of our experience are really nothing more than his manifestations.

Now consider the opposite extreme from this point of view. Suppose you take the libertarian position that the state has absolutely no rights over any resources, or any say over how they are to be used, other than the bare minimum necessary in order to carry out the “minimal state” or “night watchman state” functions of protecting individual rights to life, liberty, and property. It is individual citizens who own almost all resources and have the right to decide how they are to be used, sold, given away, or otherwise exchanged in free market transactions. Government serves only to keep the system humming by enforcing contracts and punishing rights violations.

This, I submit, is roughly analogous to the mere conservationist model, on which God merely keeps things in existence from moment to moment while they operate completely independently of him. And the more extreme anarcho-capitalist version of libertarianism, which privatizes everything and abolishes the state entirely, is, by extension, analogous to deleting God from even a conserving role vis-à-vis the world, resulting in atheism.

Now, in an earlier post I have expounded the traditional natural law conception of the state, which can be seen as a kind of middle ground position between socialism and libertarianism insofar as it is guided by the principles of subsidiarity and solidarity – principles which reflect our nature as rational social animals. As socialanimals, we come into the world not as individualist atoms having no need for or obligations toward others, but rather as members of communities – the family first and foremost, but also the local community, the nation, and ultimately the human race as a whole. As rational animals, we require a considerable range of freedom of thought and action in order to realize the ends toward which we are directed by our nature, including our social ends.

Solidarity and subsidiarity balance these considerations. As organic parts of larger social wholes, our flourishing as individuals goes hand in hand with that of those larger wholes, just as the flourishing of a part of the body goes hand in hand with that of the whole organism. The eye or the foot can flourish only if the whole body does, and the whole body can flourish only insofar as parts like the eye and foot do. Just as these parts must do their part relative to the whole body, so too must the individual do his part relative to the family, the nation, etc. And just as the whole organism must guarantee the health of its parts, so too do larger social orders have an obligation to each individual member. Solidarity thus rules out a libertarian or individualist model on which we have no obligations to others other than those we consent to. That would be like the eye or foot having no natural ordering to the good of the body as a whole, or the body as a whole having no natural ordering to the good of these parts.

On the other hand, given our rationality, the organic analogy is not a perfect one. Each of us has a capacity for individual thought and action that literal body parts do not have, and which entails that we are more than mere cells or organs of a larger social body. Literal body parts cannot understand themselves and their relation to the whole body, or choose whether and how to fulfill their roles relative to the whole. We cando so, and to flourish as rational agents we thus require as much freedom of thought and action as is consistent with our need for and obligations to larger social orders. There is also the consideration that the organic analogy is stronger the more proximate is the social whole of which one is a part. Our needs and obligations relative to the familyare stronger than our needs and obligations relative to the nation, and our needs and obligations relative to the nation are stronger than our needs and obligations relative to humanity as a whole. Hence the natural law model entails a special regard for family and nation over the “global community,” even if the latter deserves some regard as well. Subsidiarity thus rules out any socialist absorption of the individual into a communal blob. It also requires that larger level social orders (such as governments) interfere with the actions of lower level orders (such as families and individuals) only where strictly necessary. The presumption is in favor of freedom of action, even if this presumption can in some cases be overridden.

Now, this natural law model of society is, I would suggest, roughly analogous to the concurrentist model of the created order’s relation to divine action. As rational animals, we really do act on our own rather than as mere extensions of society, just as created things really do have causal efficacy of their own rather than being nothing more than manifestations of God’s action. As socialanimals, we nevertheless really do depend on larger social wholes for our capacity to act as rational creatures, just as created things depend on God for their capacity to act at all. The natural law model is a middle ground conception of the relation of individual and society falling between the socialist and libertarian extremes, just as the concurrentist model is a middle ground conception of the relation of created things to God falling between the occasionalist and mere conservationist extremes. Or to extend the analogy in a slightly more fine-grained way, the sequence:

pantheism, occasionalism, concurrentism, mere conservationism, atheism

is roughly analogous to the sequence:

totalitarian socialism, egalitarian socialism, natural law, libertarianism, anarcho-capitalism

I suggest only that there is an interesting parallelism here, and not that the analogy could be pushed much further than what I have already said. And it goes without saying that there are all sorts of ways that the analogy might break down. Nor am I claiming that there are any interesting practical implications of this analogy. It just struck me that there is an analogy here, that’s all. It is also important not to misunderstand the point of the analogy. I am not claiming that the state is divine, or that there is necessarily any special connection between anarcho-capitalism and atheism, or any special connection between socialism and pantheism! None of those things is true, and none of them follow from the analogy.

Published on February 15, 2020 12:31

Edward Feser's Blog

- Edward Feser's profile

- 329 followers

Edward Feser isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.