Edward Feser's Blog, page 39

April 30, 2020

The burden of proof is on those who impose burdens (Updated)

I have argued both that the lockdown was a justifiable initial reaction to the Covid-19 crisis, and that skeptics ought nevertheless to be listened to, and listened to more earnestly the longer the lockdown goes on. Here’s one front line doctor who argues that it has gone on long enough and should be eased up. Is he right? Maybe, though I don’t have the expertise to answer with certainty, and I’m not addressing that question here anyway. What I am sure of is this much: The burden of proof is not in the first place on him and people of like mind to show that the lockdown should be ended. The burden is on defenders of the lockdown to show that it shouldn’t be.This is especially so given that the initial justification for the lockdown (the prospect of overwhelmed hospitals and shortages of ventilators and other medical equipment) no longer applies. Not to mention the fact that we can be certain that the lockdown is causing massive damage to people’s livelihoods and savings, whereas we are notcertain that a general lockdown (as opposed, say, to a targeted lockdown of the elderly and those with special health problems) really is the most effective way to deal with Covid-19. Not to mention Sweden.

I have argued both that the lockdown was a justifiable initial reaction to the Covid-19 crisis, and that skeptics ought nevertheless to be listened to, and listened to more earnestly the longer the lockdown goes on. Here’s one front line doctor who argues that it has gone on long enough and should be eased up. Is he right? Maybe, though I don’t have the expertise to answer with certainty, and I’m not addressing that question here anyway. What I am sure of is this much: The burden of proof is not in the first place on him and people of like mind to show that the lockdown should be ended. The burden is on defenders of the lockdown to show that it shouldn’t be.This is especially so given that the initial justification for the lockdown (the prospect of overwhelmed hospitals and shortages of ventilators and other medical equipment) no longer applies. Not to mention the fact that we can be certain that the lockdown is causing massive damage to people’s livelihoods and savings, whereas we are notcertain that a general lockdown (as opposed, say, to a targeted lockdown of the elderly and those with special health problems) really is the most effective way to deal with Covid-19. Not to mention Sweden.The issue is not just that doing massive damage to the economy is, if unnecessary, imprudent in the extreme – though, to say the very least, it most certainly is that. It’s that the lockdown entails actions that, in ordinary circumstances, would be very gravely immoral.

When a surgeon contemplates sticking a scalpel into you, it isn’t merely a matter of weighing the costs and benefits of prima facie equally justifiable courses of action, and then opting for what strikes him as on balance the best one. Rather, there is an extremely strong moral presumption against his taking such action. And if he tells you that he nevertheless thinks he should do it, the burden is not on you to convince him that he shouldn’t, but on him to convince you that he should. He must not do it otherwise. And notice that this remains the case even though he is the expert.

Now, all things being equal, temporarily forbidding someone to work is, of course, not as grave as doing surgery on him. But there is nevertheless a very strong moral presumption against the former as well. As Fr. John Naugle reminds us in an essay at Rorate Caeli, laborers have a right under natural law to work to provide for themselves and their families. To interfere with their doing so when such interference is not absolutely necessary is a grave offense against social justice (and not merely against prudence), certainly as social justice is understood in the natural law tradition and in Catholic moral theology.

Hence, governmental authorities must not treat permitting and forbidding such work as prima facie equally legitimate courses of action, either of which might be chosen depending on which one strikes them as having on balance the best consequences. Rather, the burden of proof is on them to show that there is no other way to prevent greater catastrophe than temporarily to suspend the right to work. And naturally, this burden is harder to overcome the longer the suspension being posited. Short of meeting this burden, they must not forbid such work.

It is no good to respond that governmental authorities can simply compensate laborers by cutting them checks for not working. For this is merely to add yet anothermeasure that is under ordinary circumstances gravely immoral, and thus only justifiable in case of emergency. It just kicks the problem back a stage. The natural law principle of subsidiarity states that the state must not take over from individuals, families, and other private institutions what they can do for themselves, including providing for themselves. As Pope Pius XI emphasized, subsidiarity is a matter of justice, not merely of prudence.

So, if governmental authorities are going to pay laborers for not working rather than allow them to work to provide for themselves, the burden of proof is on them to show that there is no other way to avoid even greater evil. Again, there is a strong moral presumption against bringing about such dependency on the state, just as there is a strong moral presumption against forbidding laborers from working.

Of course, a difference between the surgery example and the case of forbidding someone to work is that a person who resists the surgery is only putting his own life at risk, whereas the rationale for the lockdown is that those who resist the lockdown order are putting the lives of others at risk. But here too, that just kicks the problem back a stage. Would a grave threat to the lives of others override the presumption against forbidding laborers from working? Sure, but now the burden of proof is on the authorities to show that letting people work really would put the lives of others at grave risk. The burden is not on critics of the lockdown to show that it would not do so.

Again, the original justification was that without the lockdown, hospitals would be overwhelmed and key medical supplies would become scarce. So, if that is no longer an issue, why do we still need the lockdown? The answer cannot be that some significant number of people will die if the virus spreads. For one thing, there is also an argument that in the long run a significant number of people will die if the population does not build up herd immunity, which would tell against continuing the lockdown. For another thing, no one calls for banning automobiles on the grounds that a significant number of traffic deaths are a certainty, and no one calls for quarantining people with flu on the grounds that a significant number of flu deaths are a certainty. So the prospect of some significant number of deaths cannot by itself be a sufficient reason.

But what if it is millions of deaths we’re talking about? Or what if ending the lockdown results in the virus roaring back and hospitals being overwhelmed after all? These prospects would seem to provide a sufficient reason. But how do we know that there would be millions of deaths? And what is the compelling evidence that the virus roaring back is likely to happen? It is not enough merely to float these as possibilities, or even as somewhat probable. We need something stronger than that.

I am not claiming that there are no good answers to those questions. I am not claiming that the presumption against continuing the lockdown cannot be overridden. What I am emphasizing is that there is such a presumption and that the burden of proof for those who think it can be overridden is a high one.

The reason this is worth emphasizing is that too many defenders of the lockdown act instead as if the burden of proof is on the other side, or so it seems to me.

For one thing, some of them seem to be operating with a double standard. If lockdown defenders change their minds or disagree among themselves about death rate estimates, the likelihood of hospitals being overwhelmed, the utility of masks, or the like, the reaction (not at all unreasonable) is to cut them a break and attribute this to the complexity of the issues and “fog of war” circumstances. By contrast, when a more skeptical scientist like John Ioannidis presents arguments that others challenge, the reaction (completely unreasonable) is to accuse him of scientific malpractice or perhaps of some suspect motive.

This is the reverse of the way you act when you recognize that the burden of proof is on you to justify massively and possibly catastrophically interfering with people’s lives. You hold yourself to higher standards and welcome criticism rather than dismissing or demonizing it.

It is no excuse that some critics of the lockdown have said stupid and inflammatory things (which they certainly have). Two wrongs don’t make a right, and all that. Furthermore, when you are doing things that might destroy people’s livelihoods and life savings, you shouldn’t be surprised if some of them overreact, and you need to cut them the same slack you demand for yourself – indeed, more slack than that. And of course, part of the reason lockdown critics have said such things is that they are overreacting to excesses on the part of lockdown defenders (such as the tendency to dismiss all criticism as “denialism”).

Defenders of the lockdown need to keep in mind that accusations of bad motives and bad thinking can cut both ways. They must be on guard against the “never let a crisis go to waste” mentality that seeks political advantage in the situation (and naturally thereby only reinforces the doubts of skeptics). They must also guard against fallacious “sunk cost” thinking that refuses to listen to criticism and looks for novel rationalizations of the lockdown, lest they have to face the prospect of having made a massive mistake. And they should not be quick to fling accusations of callousness at those who disagree with them, especially when they tend to be precisely the people least affected by the lockdown (e.g. professional writers who are pretty much doing what they would have done anyway and who face no prospect of job loss).

Everyone should make an extra effort at showing humility during this crisis, but especially those who are imposing enormous costs on others, where reasonable people can disagree about the necessity and efficacy of those costs.

UPDATE 5/1: Matt Taibbi does his usual service of calling BS on his fellow left-wingers. If liberal defenders of the lockdown don’t want people to suspect them of having an authoritarian agenda, they might consider not badmouthing free speech, praising the methods of the Chinese government, or revising history Orwell-style by pretending that it is non-experts and conservatives alone who initially minimized the coronavirus threat.

Published on April 30, 2020 13:37

The burden of proof is on those who impose burdens

I have argued both that the lockdown was a justifiable initial reaction to the Covid-19 crisis, and that skeptics ought nevertheless to be listened to, and listened to more earnestly the longer the lockdown goes on. Here’s one front line doctor who argues that it has gone on long enough and should be eased up. Is he right? Maybe, though I don’t have the expertise to answer with certainty, and I’m not addressing that question here anyway. What I am sure of is this much: The burden of proof is not in the first place on him and people of like mind to show that the lockdown should be ended. The burden is on defenders of the lockdown to show that it shouldn’t be. This is especially so given that the initial justification for the lockdown (the prospect of overwhelmed hospitals and shortages of ventilators and other medical equipment) no longer applies. Not to mention the fact that we can be certain that the lockdown is causing massive damage to people’s livelihoods and savings, whereas we are notcertain that a general lockdown (as opposed, say, to a targeted lockdown of the elderly and those with special health problems) really is the most effective way to deal with Covid-19. Not to mention Sweden.

I have argued both that the lockdown was a justifiable initial reaction to the Covid-19 crisis, and that skeptics ought nevertheless to be listened to, and listened to more earnestly the longer the lockdown goes on. Here’s one front line doctor who argues that it has gone on long enough and should be eased up. Is he right? Maybe, though I don’t have the expertise to answer with certainty, and I’m not addressing that question here anyway. What I am sure of is this much: The burden of proof is not in the first place on him and people of like mind to show that the lockdown should be ended. The burden is on defenders of the lockdown to show that it shouldn’t be. This is especially so given that the initial justification for the lockdown (the prospect of overwhelmed hospitals and shortages of ventilators and other medical equipment) no longer applies. Not to mention the fact that we can be certain that the lockdown is causing massive damage to people’s livelihoods and savings, whereas we are notcertain that a general lockdown (as opposed, say, to a targeted lockdown of the elderly and those with special health problems) really is the most effective way to deal with Covid-19. Not to mention Sweden.The issue is not just that doing massive damage to the economy is, if unnecessary, imprudent in the extreme – though, to say the very least, it most certainly is that. It’s that the lockdown entails actions that, in ordinary circumstances, would be very gravely immoral.

When a surgeon contemplates sticking a scalpel into you, it isn’t merely a matter of weighing the costs and benefits of prima facie equally justifiable courses of action, and then opting for what strikes him as on balance the best one. Rather, there is an extremely strong moral presumption against his taking such action. And if he tells you that he nevertheless thinks he should do it, the burden is not on you to convince him that he shouldn’t, but on him to convince you that he should. He must not do it otherwise. And notice that this remains the case even though he is the expert.

Now, all things being equal, temporarily forbidding someone to work is, of course, not as grave as doing surgery on him. But there is nevertheless a very strong moral presumption against the former as well. As Fr. John Naugle reminds us in an essay at Rorate Caeli, laborers have a right under natural law to work to provide for themselves and their families. To interfere with their doing so when such interference is not absolutely necessary is a grave offense against social justice (and not merely against prudence), certainly as social justice is understood in the natural law tradition and in Catholic moral theology.

Hence, governmental authorities must not treat permitting and forbidding such work as prima facie equally legitimate courses of action, either of which might be chosen depending on which one strikes them as having on balance the best consequences. Rather, the burden of proof is on them to show that there is no other way to prevent greater catastrophe than temporarily to suspend the right to work. And naturally, this burden is harder to overcome the longer the suspension being posited. Short of meeting this burden, they must not forbid such work.

It is no good to respond that governmental authorities can simply compensate laborers by cutting them checks for not working. For this is merely to add yet anothermeasure that is under ordinary circumstances gravely immoral, and thus only justifiable in case of emergency. It just kicks the problem back a stage. The natural law principle of subsidiarity states that the state must not take over from individuals, families, and other private institutions what they can do for themselves, including providing for themselves. As Pope Pius XI emphasized, subsidiarity is a matter of justice, not merely of prudence.

So, if governmental authorities are going to pay laborers for not working rather than allow them to work to provide for themselves, the burden of proof is on them to show that there is no other way to avoid even greater evil. Again, there is a strong moral presumption against bringing about such dependency on the state, just as there is a strong moral presumption against forbidding laborers from working.

Of course, a difference between the surgery example and the case of forbidding someone to work is that a person who resists the surgery is only putting his own life at risk, whereas the rationale for the lockdown is that those who resist the lockdown order are putting the lives of others at risk. But here too, that just kicks the problem back a stage. Would a grave threat to the lives of others override the presumption against forbidding laborers from working? Sure, but now the burden of proof is on the authorities to show that letting people work really would put the lives of others at grave risk. The burden is not on critics of the lockdown to show that it would not do so.

Again, the original justification was that without the lockdown, hospitals would be overwhelmed and key medical supplies would become scarce. So, if that is no longer an issue, why do we still need the lockdown? The answer cannot be that some significant number of people will die if the virus spreads. For one thing, there is also an argument that in the long run a significant number of people will die if the population does not build up herd immunity, which would tell against continuing the lockdown. For another thing, no one calls for banning automobiles on the grounds that a significant number of traffic deaths are a certainty, and no one calls for quarantining people with flu on the grounds that a significant number of flu deaths are a certainty. So the prospect of some significant number of deaths cannot by itself be a sufficient reason.

But what if it is millions of deaths we’re talking about? Or what if ending the lockdown results in the virus roaring back and hospitals being overwhelmed after all? These prospects would seem to provide a sufficient reason. But how do we know that there would be millions of deaths? And what is the compelling evidence that the virus roaring back is likely to happen? It is not enough merely to float these as possibilities, or even as somewhat probable. We need something stronger than that.

I am not claiming that there are no good answers to those questions. I am not claiming that the presumption against continuing the lockdown cannot be overridden. What I am emphasizing is that there is such a presumption and that the burden of proof for those who think it can be overridden is a high one.

The reason this is worth emphasizing is that too many defenders of the lockdown act instead as if the burden of proof is on the other side, or so it seems to me.

For one thing, some of them seem to be operating with a double standard. If lockdown defenders change their minds or disagree among themselves about death rate estimates, the likelihood of hospitals being overwhelmed, the utility of masks, or the like, the reaction (not at all unreasonable) is to cut them a break and attribute this to the complexity of the issues and “fog of war” circumstances. By contrast, when a more skeptical scientist like John Ioannidis presents arguments that others challenge, the reaction (completely unreasonable) is to accuse him of scientific malpractice or perhaps of some suspect motive.

This is the reverse of the way you act when you recognize that the burden of proof is on you to justify massively and possibly catastrophically interfering with people’s lives. You hold yourself to higher standards and welcome criticism rather than dismissing or demonizing it.

It is no excuse that some critics of the lockdown have said stupid and inflammatory things (which they certainly have). Two wrongs don’t make a right, and all that. Furthermore, when you are doing things that might destroy people’s livelihoods and life savings, you shouldn’t be surprised if some of them overreact, and you need to cut them the same slack you demand for yourself – indeed, more slack than that. And of course, part of the reason lockdown critics have said such things is that they are overreacting to excesses on the part of lockdown defenders (such as the tendency to dismiss all criticism as “denialism”).

Defenders of the lockdown need to keep in mind that accusations of bad motives and bad thinking can cut both ways. They must be on guard against the “never let a crisis go to waste” mentality that seeks political advantage in the situation (and naturally thereby only reinforces the doubts of skeptics). They must also guard against fallacious “sunk cost” thinking that refuses to listen to criticism and looks for novel rationalizations of the lockdown, lest they have to face the prospect of having made a massive mistake. And they should not be quick to fling accusations of callousness at those who disagree with them, especially when they tend to be precisely the people least affected by the lockdown (e.g. professional writers who are pretty much doing what they would have done anyway and who face no prospect of job loss).

Everyone should make an extra effort at showing humility during this crisis, but especially those who are imposing enormous costs on others, where reasonable people can disagree about the necessity and efficacy of those costs.

Published on April 30, 2020 13:37

April 23, 2020

Links for the lockdown

Thomas Osborne’s new book Aquinas’s Ethics, part of the Cambridge Elements series, is available online for free for a month.

Thomas Osborne’s new book Aquinas’s Ethics, part of the Cambridge Elements series, is available online for free for a month.How should a Thomist deal with a pandemic? Robert Koons proposes some general principles, at Public Discourse.

At Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews, Thomas Nagel reviews Richard Swinburne’s Are We Bodies or Souls? C. C. Pecknold on Maritain versus De Koninck on the common good, at First Things.

At the Claremont Review of Books, Christopher Caldwell on the downside of the 1980s.

Mark Dooley on the last days of Roger Scruton, at The Critic.

At Pints with Aquinas, Matt Fradd interviews William Lane Craig.

Matthew Cobb on why the brain is not a computer, at The Guardian.

Ray Monk on forgotten philosopher G. E. Moore, at Prospect.

Mary Eberstadt’s new book on the sexual revolution and identity politics is reviewed at the Claremont Review of Books.

At The American Conservative, Bradley Birzer on jazzman Dave Brubeck.

New books: Aidan Nichols, The Theologian's Enterprise ; Lloyd Gerson, Platonism and Naturalism ; Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange, Philosophizing in Faith ; and Turner Nevitt and Brian Davies, Thomas Aquinas's Quodlibetal Questions. Simpson, Koons, and Teh’s anthology Neo-Aristotelian Perspectives on Contemporary Science is now available in paperback.

Alex Byrne’s paper “Are women adult human females?” appears in Philosophical Studies. At Quillette, a writer with gender dysphoria defends biological reality. At Medium, philosopher Kathleen Stock defends free debate about transgender issues.

Nerds on Earth on Jim Shooter , the controversial editor-in-chief of Marvel Comics during the 1980s who arguably saved the company. But can comics survive the Covid-19 lockdown?

David Greg Taylor is a former underground comics artist with an interest in Aristotle and philosophy. He is returning to comics with his series Blueboy Brown: The Adventures of a Family .

Commonweal on what Orwell would think of the contemporary Left.

The Guardian takes a closer look at Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey.

The New Republic asks: What happened to Jordan Peterson?

The story of Encounter magazine, at The Critic. The death of Mad magazine’s Mort Drucker, at The Hollywood Reporter.

At Walking Christian, Gil Sanders comments on my recent debate with Graham Oppy.

At First Things, Michael Pakaluk and David Bentley Hart debate Hart’s book That All Shall Be Saved. Pakaluk has more to say at The Catholic Thing, hereand here.

Conversations on early modern philosophy. At 3:16, Richard Marshall interviews philosophers Michael Della Rocca, Richard T. W. Arthur, and Charlie Huenemann.

Wilfred McClay on what Freud got right, at the Hedgehog Review.

At New Statesman, John Gray on John Cottingham’s new book on the soul.

Published on April 23, 2020 14:08

April 19, 2020

Kremer on classical theism

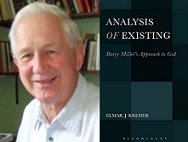

At YouTube, philosopher Elmar Kremer provides a useful multi-part introduction to the dispute between classical theism and theistic personalism, as part of the Wireless Philosophy video series. Here are links to each of the installments:

At YouTube, philosopher Elmar Kremer provides a useful multi-part introduction to the dispute between classical theism and theistic personalism, as part of the Wireless Philosophy video series. Here are links to each of the installments: Two conceptions of God

In defense of classical theism

Divine causality

God’s knowledge

God’s goodness

The problem of evil

Responding to atheism

You can also find all seven videos collected together at the Wireless Philosophy website.

Kremer is also the author of the important book Analysis of Existing: Barry Miller's Approach to God .

(Miller, in turn, was the author of several important works, including A Most Unlikely God, a must-read for anyone who wants to understand classical theism and divine simplicity in depth. Unfortunately, it is out of print and hard to get hold of. But you can find chapter 1 online and read reviews of the book by Bill Vallicella and Bonald.)

Published on April 19, 2020 14:50

April 16, 2020

The lockdown’s loyal opposition

At First Things, Fr. Thomas Joseph White has defended the Covid-19 lockdown, whereas Rusty Reno has criticized it. As I said last week, I agree with Fr. Thomas Joseph but I also believe that reason, charity, and the common good require serious engagement with skeptics like Rusty – and that this is moretrue, rather than less, the longer the lockdown goes on. Meanwhile, at The Bulwark, conservative lockdown defender Jonathan V. Last tells us that he won’t link even to Fr. Thomas Joseph’s article, let alone Rusty’s. The reason is that Fr. Thomas Joseph’s article “made matters worse, not better” by granting “legitimacy” to the idea that “there are really two sides to the issue, and that reasonable and intelligent people can disagree.” He compares Rusty’s skepticism to that of flat-earthers and anti-vaxxers.This is outrageous. Does it not occur to Last that the surest way to reinforce skepticism is precisely to demonize it, even when it is expressed by a serious writer and thinker like Rusty? When you don’t bother to respond to an argument with a counterargument, people will naturally suspect that the reason is that you can’t. And when people think their sincere concerns are not being given a fair hearing, they are only going to be hardened in their position, not shamed out of it.

At First Things, Fr. Thomas Joseph White has defended the Covid-19 lockdown, whereas Rusty Reno has criticized it. As I said last week, I agree with Fr. Thomas Joseph but I also believe that reason, charity, and the common good require serious engagement with skeptics like Rusty – and that this is moretrue, rather than less, the longer the lockdown goes on. Meanwhile, at The Bulwark, conservative lockdown defender Jonathan V. Last tells us that he won’t link even to Fr. Thomas Joseph’s article, let alone Rusty’s. The reason is that Fr. Thomas Joseph’s article “made matters worse, not better” by granting “legitimacy” to the idea that “there are really two sides to the issue, and that reasonable and intelligent people can disagree.” He compares Rusty’s skepticism to that of flat-earthers and anti-vaxxers.This is outrageous. Does it not occur to Last that the surest way to reinforce skepticism is precisely to demonize it, even when it is expressed by a serious writer and thinker like Rusty? When you don’t bother to respond to an argument with a counterargument, people will naturally suspect that the reason is that you can’t. And when people think their sincere concerns are not being given a fair hearing, they are only going to be hardened in their position, not shamed out of it.By no means is this merely a matter of good public relations strategy. For one thing, the lockdown, however temporarily necessary, is an extreme and dangerous remedy and one that has imposed massive inconveniences on people, not to mention threatened their livelihoods. It is unreasonable not to cut the skeptics some slack even when they make intemperate remarks. Defenders of the lockdown also need to keep in mind that intemperate things have been said and done by people on our side too.

For another thing, refusing even to engage with the arguments of one’s opponents is a recipe for confirmation bias, circular reasoning, and other forms of dogmatism. If an argument is wrong, then you should be able to explain how it is, rather than simply dismissing it. Otherwise you are stuck on an intellectual merry-go-round: “People who believe X aren’t even worthy of a reasoned response, because their arguments are so awful; and I know their arguments must be awful because no one who believes something like X could possibly be worthy of a reasoned response.”

Such question-begging condescension is bad enough in the best of times. It is potentially catastrophic in our current circumstances. Given how damaging the lockdown is the longer it goes on, it would be insane not to welcomeconstructive criticism, and regularly to revisit the issue of how long the lockdown ought to continue, given constantly changing circumstances.

To be sure, the fact that the estimated death toll has now been revised downward by no means shows that the lockdown to this point was not necessary. It is, however, reasonable for people to ask how soon it can end, consistent with avoiding a resurgence of the virus. I have no opinion to offer, other than the conventional one that widespread testing is essential. To that I would add only that two extremes need to be avoided.

The first extreme is dogmatically to parrot lurid journalistic accounts of every nightmare scenario that “the science” is purportedly revealing to us, as if they were holy writ. As the Covid-19 lockdown started to ramp up in the U.S. a month ago, one of the skeptical voices I took most seriously was that of Stanford epidemiologist John Ioannidis, with whose work I was familiar from his famous paper “Why Most Published Research Findings Are False.” Anyone familiar with the points made in that paper would be wary of too quickly accepting any bold claim made on the basis of current research, especiallywhen it is filtered through the keyboard of a journalist. Pathologist John Lee has more recently offered a reminder of how important it is to keep the methodological problems in mind when assessing claims about Covid-19.

Naturally, though, there is another extreme, which is to make of the fallibility of research findings an excuse glibly to dismiss them. To observe that Sherlock Holmes is not infallible is hardly grounds to think him incompetent, or to judge yourself to be a better detective than he is. It no less ridiculous for radio hosts and Twitter warriors to decide that they know more than the epidemiologists, on the grounds that the latter have revised their opinions. Moreover, in a crisis situation, fallible research is better than none at all, and all we have to go on. As others pointed out a month ago, Ioannidis’s own reasonable reservations did not entail that the scientific evidence was then too weak to act on.

As I have said before, the lesson of all this is notthat we might as well throw up our hands and cannot arrive at a right answer. The lesson is to calm down and realize that things might be more complicated than whatever it was you read today in your Twitter feed or at your favorite political website. But that’s true for the lockdown’s defenders too, and not just its critics.

Here’s a good debate at Catholic Heraldbetween Helen Andrews and Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry.

Published on April 16, 2020 17:45

April 14, 2020

Review of Scientism

My brief review of the anthology

Scientism: Prospects and Problems

, edited by Jeroen de Ridder, Rik Peels, and René van Woudenberg, appears in the December 2019 issue of Review of Metaphysics. (The preview you see in that link leaves out only the last paragraph and a half or so of the review.)

My brief review of the anthology

Scientism: Prospects and Problems

, edited by Jeroen de Ridder, Rik Peels, and René van Woudenberg, appears in the December 2019 issue of Review of Metaphysics. (The preview you see in that link leaves out only the last paragraph and a half or so of the review.)

Published on April 14, 2020 12:04

April 12, 2020

The lesson of the Resurrection

The lesson of the Resurrection is that the significance of our bodily life and its sufferings should be neither overstated nor understated. It is to see the middle ground between materialism and Platonism. In our decadent sensualist age, the anti-materialist message is perhaps the more obvious one. The secularist can see no fate worse than unfulfilled earthly ambitions, unhappy marriages, unpaid bills, poor health, and the deathbed. And no greater good than the avoidance of such things. Woody Allen captures the mindset well: “Life is full of misery, loneliness, and suffering – and it’s all over much too soon.” This is pathetic. Whether your hero is Socrates, St. Polycarp, or that glorious mashup of both, St. Justin Martyr, you know that there is no one so blind as he who cannot see the perpetuity beyond our three score and ten. Death ends only our time in the waiting room. Some waiting rooms are excruciatingly boring and uncomfortable. Some are so filled with entertainments that you’re disappointed when it’s time to leave. Either way, they’re just waiting rooms, and so is this life.

The lesson of the Resurrection is that the significance of our bodily life and its sufferings should be neither overstated nor understated. It is to see the middle ground between materialism and Platonism. In our decadent sensualist age, the anti-materialist message is perhaps the more obvious one. The secularist can see no fate worse than unfulfilled earthly ambitions, unhappy marriages, unpaid bills, poor health, and the deathbed. And no greater good than the avoidance of such things. Woody Allen captures the mindset well: “Life is full of misery, loneliness, and suffering – and it’s all over much too soon.” This is pathetic. Whether your hero is Socrates, St. Polycarp, or that glorious mashup of both, St. Justin Martyr, you know that there is no one so blind as he who cannot see the perpetuity beyond our three score and ten. Death ends only our time in the waiting room. Some waiting rooms are excruciatingly boring and uncomfortable. Some are so filled with entertainments that you’re disappointed when it’s time to leave. Either way, they’re just waiting rooms, and so is this life.But that is not because we have immortal souls, and it is not because worldly things don’t matter. To be sure, we do have immortal souls, and worldly things don’t matter in themselves. But an immortal soul is not a person, full stop. It is the remnantof a person, and the loss of its body is a grave injury rather than a liberation. And the soul’s perpetual port-mortem character is determined by what we did and what we suffered in this life.

This is where the anti-Platonic message comes in. We are embodied by naturerather than by accident. The soul is not whole without the flesh. Nor is it destined to be purged of all traces of the individual that lived and breathed and suffered and died, like the impersonal atmanof Hinduism. The lesson of the Resurrection is not that death is not the end of your soul. It is that death is not the end of you as an embodied individual. And it tells us, not that the sufferings of this life will be forgotten, but that they will be redeemed. A perpetualgood will be drawn out of a finite harm, like wine out of water.

The resurrected Christ carries his wounds perpetually, as trophies, Aquinas tells us. They are like the scar that an athlete wouldn’t dream of correcting through cosmetic surgery, lest he be deprived of a reminder of what he has earned. Similarly, the lesson of the Resurrection is that the broken heart you suffer now, the smashing of your worldly hopes, the pain of a loved one’s death or of your own failing body – the memory of all of that will, after death, be like one of Christ’s wounds. It will take on a radically different character, and indeed be seen for what it always truly was, part of the purging and perfecting of a spiritual athlete.

For those who love God , anyway. For there is a frightful flip side of the Resurrection, insofar as the wicked no less than the righteous have their bodies restored to them, and their characters too are perpetually set by what they set their hearts on in this life. The memory of their illicit pleasures, of their attachment to mammon, of their lust for fame and power, will ache like a perpetual hangover, an unending reminder of their stupidity and shortsightedness. “Assuredly, they have their reward.”

That is a reward more to be feared than death. But death is indeed frightful. I love and honor Socrates, as any philosopher should. But his death, noble as it was, was not the death of a man who knew death for what it really is. To be sure, his partial truth is far closer to the whole truth than the partial truth of the materialist. Better by far to be a pagan of the Platonist stripe than that sad, contemptible thing Nietzsche called the “Last Man,” the comfort-seeking individualist of liberal secular modernity.

Still, judging from the Phaedo, you’d think that death is essentially a matter of falling asleep during a philosophical conversation with friends. But the reality of death is better captured in other images – of St. Ignatius of Antioch in the teeth of the lions, or St. Polycarp in the flames.

And yet, amazingly, they met these ghastly ends in a manner no less sanguine than that of Socrates. The Last Man tells us: “Death is horrible, so fear it!” Socrates tells us: “Death is not horrible, so don’t fear it!” Christianity tells us: “Death is horrible – but don’t fear it!”

Related posts:

The meaning of the Resurrection

The last enemy

What is a soul?

Published on April 12, 2020 13:01

April 10, 2020

Some thoughts on the COVID-19 crisis

I commend to you Fr. Thomas Joseph White’s First Things essay on the COVID-19 situation and the bishops’ response to it. It exhibits his characteristic good sense and charity. First Things editor Rusty Reno, with whom Fr. Thomas Joseph disagrees, exhibits his characteristic magnanimity and intellectual honesty in running it. My sympathies are with Fr. Thomas Joseph’s views rather than Rusty’s, but I have been appalled by the nastiness of others who have responded to Rusty (who is a good man and a serious thinker and writer who deserves to be engaged with seriously). Our situation calls for patience with one another and the calm exchange of opposing views, for the sake of the common good. Too many have instead treated the debate over COVID-19 as an extension of hostilities that pre-existed the crisis. This is gravely contrary to reason and charity. The situation is as complicated as it is dire. The consequences of either underreacting or overreacting could be catastrophic. However, in dealing with a pandemic, time is of the essence, and one has to act before it is too late, on the basis of a fallible judgment call. For this reason, authorities who decided on a lockdown opted to risk erring on the side of possible overreaction, and to me this seems reasonable. It also seems to me unreasonable to attribute suspect motives (as opposed to an error in judgment) to those who made these decisions, since they hardly benefit from economic catastrophe.

I commend to you Fr. Thomas Joseph White’s First Things essay on the COVID-19 situation and the bishops’ response to it. It exhibits his characteristic good sense and charity. First Things editor Rusty Reno, with whom Fr. Thomas Joseph disagrees, exhibits his characteristic magnanimity and intellectual honesty in running it. My sympathies are with Fr. Thomas Joseph’s views rather than Rusty’s, but I have been appalled by the nastiness of others who have responded to Rusty (who is a good man and a serious thinker and writer who deserves to be engaged with seriously). Our situation calls for patience with one another and the calm exchange of opposing views, for the sake of the common good. Too many have instead treated the debate over COVID-19 as an extension of hostilities that pre-existed the crisis. This is gravely contrary to reason and charity. The situation is as complicated as it is dire. The consequences of either underreacting or overreacting could be catastrophic. However, in dealing with a pandemic, time is of the essence, and one has to act before it is too late, on the basis of a fallible judgment call. For this reason, authorities who decided on a lockdown opted to risk erring on the side of possible overreaction, and to me this seems reasonable. It also seems to me unreasonable to attribute suspect motives (as opposed to an error in judgment) to those who made these decisions, since they hardly benefit from economic catastrophe.It is also unreasonable to condemn their actions on the grounds that the models they used in making their decisions are fallible, and indeed have since been modified. Models are all anyone has to go on in situations like this, and the skeptics have to make their own judgments on the basis of their own equally fallible models. Moreover, if infection and death rates turn out to be lower than was initially feared, then this might, of course, be attributed precisely to the efficacy of the measures taken in light of the models.

Skeptics will rightly point out that there is a danger here of making claims that are unfalsifiable. But they need to keep in mind that that is a point that cuts both ways. In the abstract, “Things would have worked out anyway, without the lockdown!” is no less unfalsifiable than “See, the lockdown worked!” What you have to do in order to test such claims is to compare cases where lockdowns were used to cases where they were not. But that is trickier than it seems because there are so many variables. What works in smaller countries may not work in larger ones. Some lockdowns might be more draconian than others, and if things work out well in the less draconian cases it will be hard to know whether to attribute that to the fact that the lockdown was less draconian or to the fact that there was a lockdown. And so on.

That is not to say that there is no right answer here. It is just to emphasize that the situation is one where complicated issues with momentous implications have to be hashed out under time constraints. Skeptics need to be heard, because any rational person will want to consider opposing views before deciding to take some drastic action. However, the skeptics ought to cut a lot of slack to those with responsibility for making those decisions.

In the short run, then, my sympathies are more with those who defend the lockdown than with those who are skeptical of it. However, in the long run those who defend the lockdown need to be more open, rather than less, to the considerations raised by the skeptics. To be sure, no one denies that the lockdown must be ended as soon as is reasonably possible, even if people disagree about what “reasonably” entails. But as time goes on, harder evidence about the nature of the virus will accumulate and we will have had more time carefully to weigh different options for dealing with it. The risk of overreaction will be harder to justify on the grounds of having to act under time constraints.

Moreover, the longer the lockdown goes on, the more the economic damage increases even as the danger posed by the virus decreases. It would be absurd and irresponsible to attribute concern about this to Wall Street greed. The potential damage includes mass unemployment, the destruction of ordinary people’s retirement plans, the depletion of their savings, social instability, and indeed the instability of the health care system itself. Authorities have to keep one eye always locked on this problem even as the other is directed at the virus.

This is why, as I say, both charity and sober debate are necessary. But there has been too little of either. Those who warned about the grave danger of COVID-19 were right. But too many of them – not all, by any means, but a disturbing number – have been prone to self-righteous grandstanding and a naked desire to politicize the crisis. Too many of the skeptics, meanwhile, have overreacted to this obnoxiousness and succumbed to the temptation to politicize the crisis in the opposite direction. In short, too many people are reacting to each otherrather than to the situation. And they too often seem more concerned with petty point-scoring rather than with trying rationally to convince each other or with seeking each other’s well-being.

In the final paragraph of his article, Fr. Thomas Joseph offers some thoughts about what true Christian charity calls for in this situation. But it is in his penultimate paragraph that he addresses what, in my opinion, is the main lesson of this crisis, as of every crisis. It is a reminder that everyday pleasures, economic well-being, political order, health, and indeed life itself, are fleeting. It is a memento mori. It is a call to get serious about more serious things. As Fr. Thomas Joseph writes, “if we simply seek to pass through all this in hasty expectation of a return to normal, perhaps we are missing the fundamental point of the exercise.”

Published on April 10, 2020 13:27

April 7, 2020

Damnation denialism

Here’s a narrative we’re all by now familiar with. Call it Narrative A:

Here’s a narrative we’re all by now familiar with. Call it Narrative A:Those who initially downplayed the dangers of COVID-19 were guilty of wishful thinking, as are those who think the crisis can be resolved either easily or soon. This is what the experts tell us, and we should listen to them. Even though those most at risk of death from the novel coronavirus are the elderly and those with preexisting medical conditions, this is a large group. Moreover, many people who won’t die from the virus will still suffer greatly, and even those with mild symptoms or none at all can still infect others. Draconian measures are called for, even at the risk of massive unemployment, the undoing of people’s retirement plans, and the depletion of their savings. Better safe than sorry. To resist these hard truths is to be guilty of “coronavirus denialism.” This narrative is now widely accepted, and I have nothing to say here in criticism of it. More to the present point, it seems to be widely accepted by Catholic bishops, who have been moved by it to suspend most public access to churches and to the sacraments. I have nothing to say here in criticism of that either.

Here’s another narrative that is also familiar, but less widely accepted. Call it Narrative B:

Those who suppose that few if any people will go to Hell are guilty of wishful thinking. This is contrary to scripture and 2,000 years of teaching from the popes, the saints, and the Church’s greatest theologians. They are the experts and we should listen to them. Even if it turned out that a minority of the human race is damned, this could still be a large number. Moreover, even those who will end up instead in Purgatory will still suffer greatly, and those who teach errors or live immoral lives out of invincible ignorance might lead others into damnation. The call for conversion to the Catholic faith and repentance from sin must be urgently pursued, even at the risk of causing grave offence and inviting serious persecution. To resist these hard truths is to be guilty of “damnation denialism.”

I am well aware that secular readers, universalists, and others will scoff at Narrative B. But this post is not directed to them. It is directed to those who claim to accept the teaching of the Catholic Church, such as the bishops.

The question for these Catholics is this: If Narrative A is compelling, how much more compelling should we find Narrative B? After all, as Christ taught: “Do not fear those who kill the body but cannot kill the soul; rather fear him who can destroy both soul and body in hell” (Matthew 10:28). Since COVID-19 attacks only the body but Hell entails the perpetual suffering of body andsoul, shouldn’t damnation be an even more urgent concern than COVID-19?

Yet most Catholics, including most priests and bishops, have for decades now seemed to regard it as far less urgent. For example, the topic of Hell rarely comes up in contemporary preaching, and when it does the emphasis is not on warning people about it, but rather on reassuring them that probably few souls if any end up there. How is this any better than reassuring people that the coronavirus will probably be no worse than a bad flu?

From the Gospels onward, the Catholic tradition has clearly emphasized urgent warning about Hell rather than reassurance. For example, when asked directly whether “few” would be saved, Christ didn’t give a reassuring answer. On the contrary, he responded:

Strive to enter by the narrow door; for many, I tell you, will seek to enter and will not be able. When once the householder has risen up and shut the door, you will begin to stand outside and to knock at the door, saying, ‘Lord, open to us.’ He will answer you, ‘I do not know where you come from.’… There you will weep and gnash your teeth, when you see Abraham and Isaac and Jacob and all the prophets in the kingdom of God and you yourselves thrust out. (Luke 13: 23-28)

And again:

Enter by the narrow gate; for the gate is wide and the way is easy, that leads to destruction, and those who enter by it are many. For the gate is narrow and the way is hard, that leads to life, and those who find it are few. (Matthew 7:13-14)

How on earth could any rational person try to square such remarks with the thesis that we have good grounds for “hope” for the salvation of all? Yet some of the same Catholics who insist on taking with the utmost gravity the medical experts’ most dire predictions about the COVID-19 death toll seem to respond to Christ’s words with a shrug. Do they take Dr. Anthony Fauci’s expertise more seriously than Christ’s?

This is not even to mention the rest of the testimony of Catholic tradition, from the pessimistic views of St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas down to Pope Pius IX’s explicit condemnationof the thesis that “good hope at least is to be entertained of the eternal salvation of all those who are not at all in the true Church of Christ.”

Of course, many will point to purported counterevidence, such as St. Paul’s observation that God “desires all men to be saved” (I Timothy 2:4). This, they claim, gives us reason to think that maybe Hell will be empty after all. This is an exceedingly weak argument. God also desires all men to avoid sin, but of course, they nevertheless sin all the time. So how does the fact that God desires all men to be saved make it likely that they will all be saved? Maybe they’ll mostly be damned, for the same reason they mostly sin – because of their free choices, with which God does not interfere despite their being contrary to what he desires.

Note that it is irrelevant that it could nevertheless in theory turn out that few are damned, just as Narrative A tells us that it is irrelevant that COVID-19 might in theory have fizzled out without draconian measures. What matters is the realistic possibility of mass damnation, just as what matters is the realistic possibility of mass death from coronavirus. The accent should be on the worst case scenario, not the best. So how is straining to find reassuring passages in scripture any more rational than cherry-picking expert medical opinion that supports the reassuring idea that the coronavirus isn’t much worse than the flu? Why do even many conservative Catholics enthusiastically promote Balthasar’s comforting views, rather than lamenting him as the Dr. Drewof damnation denialism?

Similarly, the Church has always insisted on baptism and conversion to the Catholic faith as crucial to the salvation of the human race. Just twenty years ago, the declaration Dominus Iesus , issued under Pope St. John Paul II, reaffirmed that, despite the possibility that non-Catholics might receive divine grace:

It is also certain that objectively speaking they are in a gravely deficient situation in comparison with those who [are] in the Church…

Thus, the certainty of the universal salvific will of God does not diminish, but rather increases the duty and urgency of the proclamation of salvation and of conversion to the Lord Jesus Christ.

Of course, the theme goes all the way back to the Great Commission, wherein Christ directed:

Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything that I have commanded you. (Matthew 28: 19-20)

Yet one almost never hears contemporary churchmen calling for conversion. On the contrary, they seem to be absolutely terrified of being thought “proselytizers,” and emphasize only “dialogue” and common ground. If a single lockdown policy urgently imposed on the entire world is the only way soberly to address the COVID-19 situation, why is there no urgency about converting non-Catholics to the one true faith so as to save their souls? How is betting on “invincible ignorance” to save most of them any safer than betting on summer weather to knock out the coronavirus?

No doubt there will be Catholics reading this inclined to dismiss it all as excessively harsh, paranoid, an overreaction, etc. But how can they consistently do so if they would condemn those who regard the current COVID-19 lockdownas excessively harsh, paranoid, an overreaction, etc.? How could someone who really believes what the Catholic Church teaches regard damnation denialism as any more respectable than coronavirus denialism?

Related posts:

How to go to hell

Does God damn you?

Why not annihilation?

A Hartless God?

No hell, no heaven

Speaking (what you take to be) hard truths ≠ hatred

Published on April 07, 2020 23:16

March 30, 2020

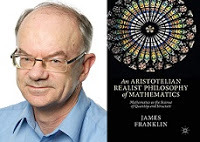

Franklin on Aristotelian realism and mathematics

At YouTube, mathematician and philosopher James Franklin, author of

An Aristotelian Realist Philosophy of Mathematics

, offers a brief introduction to the subject. Also check out the website he and some others have devoted to Aristotelian realism, as well as Franklin’s personal website.

At YouTube, mathematician and philosopher James Franklin, author of

An Aristotelian Realist Philosophy of Mathematics

, offers a brief introduction to the subject. Also check out the website he and some others have devoted to Aristotelian realism, as well as Franklin’s personal website.A public lecture on mathematics and ethics that Franklin is scheduled to give on April 2 will, in light of the COVID-19 situation, be pre-recorded and posted online.

Published on March 30, 2020 19:08

Edward Feser's Blog

- Edward Feser's profile

- 329 followers

Edward Feser isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.