Edward Feser's Blog, page 37

July 17, 2020

Plato predicted woke tyranny

What we are seeing around us today may well turn out to be a transition from decadent democratic egalitarianism to tyranny, as Plato described the process in The Republic. I spell it out in a new essay at The American Mind.

What we are seeing around us today may well turn out to be a transition from decadent democratic egalitarianism to tyranny, as Plato described the process in The Republic. I spell it out in a new essay at The American Mind.

Published on July 17, 2020 16:12

July 13, 2020

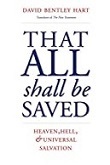

Review of Hart

My review of David Bentley Hart’s

That All Shall Be Saved: Heaven, Hell, and Universal Salvation

appears in the latest issue of Catholic Herald. You can read it online here. (It’s behind a paywall, but when you click on the link you will see instructions telling you how to register for free access.)

My review of David Bentley Hart’s

That All Shall Be Saved: Heaven, Hell, and Universal Salvation

appears in the latest issue of Catholic Herald. You can read it online here. (It’s behind a paywall, but when you click on the link you will see instructions telling you how to register for free access.) Here are some earlier posts that explore in greater detail some of the issues raised in the review: How to go to hell

Does God damn you?

Why not annihilation?

A Hartless God?

No hell, no heaven

Speaking (what you take to be) hard truths ≠ hatred

Damnation denialism

Published on July 13, 2020 09:10

July 8, 2020

Other minds and modern philosophy

The “problem of other minds” goes like this. I have direct access to my own thoughts and experiences, but not to yours. I can perceive only your body and behavior. So how do I know you really have any thoughts and experiences? Maybe you merely behave as if you had them, but in reality you are a “zombie” in the philosophy of mind sense, devoid of conscious awareness. And maybe this is true of everyone other than me. How do I know that any minds at all exist other than my own? One traditional answer to the problem is the “argument from analogy.” I know from my own case that when, for example, I flinch and cry out upon injury, there is a sensation of pain associated with this behavioral reaction, and that when I say things like “It’s going to rain” that’s because I have the thought that it is going to rain. So, by analogy, I can infer from the fact that you also flinch and cry out, and also say things like “It’s going to rain,” that you too must have thoughts and sensations of pain. In modern philosophy this argument is put forward by writers like John Stuart Mill, and it is sometimes suggested that one can find something like it in Augustine’s On the Trinity, Book 8, Chapter 6.

The “problem of other minds” goes like this. I have direct access to my own thoughts and experiences, but not to yours. I can perceive only your body and behavior. So how do I know you really have any thoughts and experiences? Maybe you merely behave as if you had them, but in reality you are a “zombie” in the philosophy of mind sense, devoid of conscious awareness. And maybe this is true of everyone other than me. How do I know that any minds at all exist other than my own? One traditional answer to the problem is the “argument from analogy.” I know from my own case that when, for example, I flinch and cry out upon injury, there is a sensation of pain associated with this behavioral reaction, and that when I say things like “It’s going to rain” that’s because I have the thought that it is going to rain. So, by analogy, I can infer from the fact that you also flinch and cry out, and also say things like “It’s going to rain,” that you too must have thoughts and sensations of pain. In modern philosophy this argument is put forward by writers like John Stuart Mill, and it is sometimes suggested that one can find something like it in Augustine’s On the Trinity, Book 8, Chapter 6.The standard objection to this argument is that it amounts to the weakest possible kind of inductive inference, a generalization from a single instance to every member of a class. There are eight billion people, and I have observed in only one case, namely my own, a correlation between thoughts and experiences on the one hand and bodily properties and behavior on the other. So how does the inference from my own case to the rest of the human race not amount to a fallacy of hasty generalization?

But the idea that there is a “problem” here, and that the solution to it is a kind of inductive generalization, are artifacts of modern philosophical assumptions. I don’t think Augustine was in fact giving an “argument from analogy” in the sense in which modern philosophers have done. He was not offering a philosophical theory in response to a philosophical problem. He was just noting how, in his view, we do in fact in everyday life know that other minds exist. Here is the relevant passage:

For we recognize the movements of bodies also, by which we perceive that others live besides ourselves, from the resemblance of ourselves; since we also so move our body in living as we observe those bodies to be moved. For even when a living body is moved, there is no way opened to our eyes to see the mind, a thing which cannot be seen by the eyes; but we perceive something to be contained in that bulk, such as is contained in ourselves, so as to move in like manner our own bulk, which is the life and the soul. Neither is this, as it were, the property of human foresight and reason, since brute animals also perceive that not only they themselves live, but also other brute animals interchangeably, and the one the other, and that we ourselves do so. Neither do they see our souls, save from the movements of the body, and that immediately and most easily by some natural agreement. Therefore we both know the mind of any one from our own, and believe also from our own of him whom we do not know. For not only do we perceive that there is a mind, but we can also know what a mind is, by reflecting upon our own: for we have a mind.

End quote. Note that Augustine attributes to non-human animals the same kind of knowledge that other things are alive (and, presumably, conscious too) that he attributes to us. But non-human animals do not engage in inductive reasoning. So, it isn’t an inductive generalization, fallacious or otherwise, that he is attributing to us either.

I submit that there are at least three assumptions more typical of modern philosophy than of ancient and medieval philosophy that underlie the idea that there is such a thing as a “problem of other minds,” and that our knowledge of other minds is grounded in a kind of inductive generalization.

The first is that genuine knowledge is always a kind of “knowing that” or propositional knowledge, as opposed to a kind of “knowing how” or tacit knowledge. (See Aristotle’s Revenge , pp. 95-113 for discussion of this distinction.) Not all modern philosophers take this view, but it is criticized by thinkers like Wittgenstein, Heidegger, Michael Polanyi, Hubert Dreyfus, et al. as typical of a Cartesian conception of rationality. The idea is that knowledge can always be analyzed into the possession of explicitly formulated propositions and inferences. If ordinary people don’t seem consciously to be entertaining such propositions and inferences, then it is sometimes claimed in response that the propositions and inferences are nevertheless present below the level of consciousness (say, as the rules and representations of a computer program implemented in the brain).

It is natural, on this model of rationality, to think that knowledge of other minds must involve some kind of inference. Wittgenstein’s critique of the whole debate over the problem of other minds might be read as claiming that knowledge of other minds is in fact a kind of tacit knowledge rather than a propositional or inferential kind of knowledge. On this view, the debate simply misunderstands the nature of our knowledge in this case.

A second relevant modern assumption is that there is a metaphysical gap between matter and consciousness that makes inferring the presence of the latter from facts about the former inherently problematic. The standard modern conception of matter inherited from the early modern “mechanical philosophy” facilitates this assumption. Matter is taken to be characterized by quantifiable primary qualities alone (size, shape, motion, etc.) and lacking anything like qualitative secondary qualities (color, sound, heat, cold, etc.), at least as common sense understands them. Hence it becomes mysterious how the qualia of conscious experience could be material, and knowledge of a thing’s material properties comes to seem insufficient to ground an inference to its having any mental properties. (This is, of course, a topic about which I’ve written many times.)

A third relevant assumption – and the one I want to focus on here – involves what we might call a Baconian conception of our knowledge of the natures of things, as opposed to an Aristotelian conception. For the Aristotelian-Scholastic position against which Francis Bacon reacted, common sense is more or less right about the natures of everyday natural objects, even if it isn’t very sophisticated. The ordinary observer correctly grasps what it is to be a stone, a tree, or a dog, even if it takes scientific investigation to understand these natures in a deeper and more sophisticated way. On this view, the senses are, you might say, friendly witnesses and just need an expert to ask the right questions in order to find out what else they know.

For Bacon, by contrast, the real natures of things are hiding behind false appearances, and sense experience is a hostile witness who must be tricked and threatened into revealing what it knows. Hence Bacon’s emphasis on slow and painstaking observations under artificial conditions, and the gradual working up from them to a general conclusion before one can claim to know what a thing of a certain kind is really like.

Also relevant is the modern idea that understanding the physical world is not a matter of uncovering the essences of things, but rather a matter of identifying the laws that relate observed phenomena. This involves formulating a general theory, deriving predictions from it, and then testing those predictions by way of a series of observations and experiments.

If that is the way that knowledge of the empirical world works, then naturally it comes to seem that whether other people really have minds is not as clear-cut as common sense supposes, and some kind of theoretical inference must be deployed in order to justify the supposition that they do. The meagerness of the evidential base in one’s own case in turn becomes a major problem, insufficient as it is for the construction of a Baconian inference.

Now, as contemporary neo-Aristotelian philosophers of science point out, this is not exactly how science in fact typically proceeds. To be sure, the Baconian emphasis on making observations under artificial experimental conditions certainly does feature in modern scientific method, but the idea of piling up instances before drawing a general conclusion does not. As Nancy Cartwright has argued, once the right experimental conditions are set up, multiple observations are not seen as necessary. She writes: “Modern experimental physics looks at the world under precisely controlled or highly contrived circumstance; and in the best of cases, one look is enough. That, I claim, is just how one looks for [Aristotelian] natures” (The Dappled World, p. 102, emphasis added).

Now, if few observations or even a single observation are all that is needed when the circumstances are right, then we have an essentially Aristotelian rather than Baconian approach to how many cases are needed in order to determine the basic nature of a thing. The difference is in the nature of the cases, not the numberof cases. The Aristotelian thinks that ordinary observation isn’t especially liable to get the nature of a thing positively wrong (even if it does not go very deep either) whereas the Baconian thinks that ordinary observation’s getting things positively wrong is a serious possibility.

Now, suppose the Baconian were correct about observation of things other than ourselves – stones, trees, dogs, etc. Suppose that common sense is indeed prone to getting the natures of these things wrong (which is, again, a stronger claim than just saying that common sense has only a superficial knowledge of their natures, which the Aristotelian would not deny).

Still, it wouldn’t follow that we are likely to get things wrong about our own nature, and prima facie that is unlikely, since in this case the knower and the thing known are the same. Of course, one could argue that there is a dramatic appearance/reality gap even here, but the point is that you would have to argue for such a claim. It is not prima facie what we would expect.

In that case, though, why couldn’t one know just from one’s own case that a physiology and behavior like ours go hand-in-hand with a psychology like ours as a matter of human nature? And then, applying this knowledge of human nature, why couldn’t one thereby know that other human beings too have mind’s like one’s own? “Problem of other minds” solved.

Again, some philosophers would of course argue that things are not as they seem even in the case of our apparent knowledge of our own minds. But the point is that that is simply not a plausible default assumption. There is a presumption in favor of our having a correct understanding of our own nature, and (given what I’ve just argued) there is, accordingly, a presumption in favor of other people having minds just like our own.

That suffices to undermine the idea that there is a frightfully difficult “problem of other minds.” The correct description of our situation is not that we don’thave good grounds for believing in other minds, and therefore have to cobble together some solution to this problem. It’s that we do have good grounds for believing that there are other minds, and therefore the philosopher who thinks otherwise can make things seem problematic only by making a number of tendentious modern (and, I would say, wrong) philosophical assumptions.

Published on July 08, 2020 11:53

July 4, 2020

The virtue of patriotism

Patriotism involves a special love for and reverence toward one’s own country. These days it is often dismissed as sentimental, unsophisticated, or even bigoted. In fact it is a moral virtue and its absence is a vice. Aquinas explains the basic reason:

Patriotism involves a special love for and reverence toward one’s own country. These days it is often dismissed as sentimental, unsophisticated, or even bigoted. In fact it is a moral virtue and its absence is a vice. Aquinas explains the basic reason:A man becomes a debtor to others in diverse ways in accord with the diverse types of their excellence and the diverse benefits that he receives from them. In both these regards, God occupies the highest place, since He is the most excellent of all and the first principle of both our being and our governance. But in second place, the principles of our being and governance are our parents and our country, by whom and in which we are born and governed. And so, after God, a man is especially indebted to his parents and to his country. Hence, just as [the virtue of] religion involves venerating God, so, at the second level, [the virtue of] piety involves venerating one’s parents and country. Now the veneration of one’s parents includes venerating all of one’s blood relatives... On the other hand, the veneration of one’s country includes the veneration of one’s fellow citizens and of all the friends of one’s country. (Summa Theologiae II-II.101.1, Freddoso translation) Love and reverence for country is thus an extension of love and reverence for parents and family, and has a similar basis. One’s country is like an extended family, and benefits one in ways analogous to the benefits provided by family. Hence, just as one owes a special gratitude and respect to one’s own parents and family that is not owed to other families, so do does one owe a special gratitude and respect to one’s own country that is not owed to other countries.

But it’s not just what your country has done for you that matters, it’s what you can do for your country. As Aquinas also argues, just as one is obliged to provide benefits to one’s own family in a way one is not obliged to provide them to other families, so too ought one to give benefits to one’s own country that one does not owe to other countries. He writes:

Augustine says… “Since one cannot do good to all, we ought to consider those chiefly who by reason of place, time or any other circumstance, by a kind of chance are more closely united to us”…

Now the order of nature is such that every natural agent pours forth its activity first and most of all on the things which are nearest to it… But the bestowal of benefits is an act of charity towards others. Therefore we ought to be most beneficent towards those who are most closely connected with us.

Now one man's connection with another may be measured in reference to the various matters in which men are engaged together; (thus the intercourse of kinsmen is in natural matters, that of fellow-citizens is in civic matters, that of the faithful is in spiritual matters, and so forth): and various benefits should be conferred in various ways according to these various connections, because we ought in preference to bestow on each one such benefits as pertain to the matter in which, speaking simply, he is most closely connected with us…

For it must be understood that, other things being equal, one ought to succor those rather who are most closely connected with us. (Summa Theologiae II-II.31.3)

As Aquinas also says, by no means does this entail that one has no obligations to help those of other countries, any more than one’s special duty to one’s own parents and family entails that one need not ever help other families. The point is just that a special concern for one’s own country and countrymen is not only not wrong, it is obligatory. As one work of Catholic moral theology says:

Piety is owed to parents and country as the authors and sustainers of our being… On account of this nobility of the formal object, filial piety and patriotism are very like to religion and rank next after it in the catalogue of virtues…

Country should be honored, not merely by the admiration one feels for its greatness in the past or present, but also and primarily by the tender feeling of veneration one has for the land that has given one birth, nurture, and education… External manifestations of piety towards country are the honors given its flag and symbols, marks of appreciation of its citizenship… and efforts to promote its true glory at home and abroad. (McHugh and Callan, Moral Theology, Volume II, pp. 412-13)

As with other virtues, the virtue of patriotism is a mean between extremes, and thus there are two corresponding vices, one of excess and one of deficiency. Here is how a couple of standard works of moral theology in the Thomistic tradition describe the first vice:

Excess is shown in this virtue by those who cultivate excessive nationalism in word and deed with consequent injury to other nations. (Prümmer, Handbook of Moral Theology, p. 211)

Patriotism should not degenerate into patriolatry, in which country is enshrined as a god, all-perfect and all-powerful, nor into jingoism or chauvinism, with their boastfulness or contempt for other nations and their disregard for international justice or charity. (McHugh and Callan, Moral Theology, Volume II, p. 414)

As with the virtue of patriotism itself, the nature and unreasonableness of this vice of excess are best understood on analogy with the case of parents and family. Even most people with a deep sentimental attachment to their own parents and family would find it bizarre to suppose that this would entail deifying them, or justify hatred and contempt for other families. But no less unreasonable would it be to take love of country to justify idolatry of country or hatred and contempt for other countries. The monstrous example of Nazi Germany has hammered home to modern people the evil of this excess.

Here is how the manuals just quoted describe the opposite extreme vice:

The virtue is violated by defect by those who boast that their attitude is cosmopolitan and adopt as their motto the old pagan saying: ubi bene, ibi patria (Prümmer, Handbook of Moral Theology, p. 211)

Disrespect for one’s country is felt when one is imbued with anti-nationalistic doctrines (e.g., the principles of Internationalism which hold that loyalty is due to a class, namely, the workers of the world or a capitalistic group, and that country should be sacrificed to selfish interests; the principle of Humanitarianism, which holds that patriotism is incompatible with love of the race; the principle of Egoism which holds that the individual has no obligations to society); it is practiced when one speaks contemptuously about country, disregards its good name or prestige, subordinates its rightful pre-eminence to a class, section, party, personal ambition, or greed, etc. (McHugh and Callan, Moral Theology, Volume II, p. 414)

Here too, the nature and unreasonableness of the vice are best understood on analogy with the case of parents and family. Suppose someone had no special regard for or loyalty toward his own parents or family, on the grounds that we should be charitable and just to everyone and that we shouldn’t regard any family with contempt. This would obviously be a perverse non sequitur. That we have obligations of justice and charity to all people and shouldn’t regard other families with contempt simply does not entail that we don’t have special obligations to our own parents and family or that we don’t owe them a special love and loyalty. In the same way, it is perverse to infer, from the premise that jingoism is wrong, the conclusion that patriotism is wrong too. Avoiding the one extreme does not justify going to the other extreme.

Accordingly, though the kind of cosmopolitanism that puts loyalty to the international community over national loyalty is often regarded these days as morally superior to patriotism, in fact it is immoral, in a way that is analogous to the immorality of refusing to have a special love and loyalty for one’s own parents and family. Similarly immoral are views which replace patriotism with loyalty to one’s economic class (as Marxism does), or one’s race (as both left-wing and right-wing brands of racism do), or one’s narrow economic interests (as global corporations do), or oneself as a sovereign individual owing nothing to any social order at all (as anarcho-libertarianism does).

It follows from all this that it is not wrong to favor immigration policies aimed at preserving the economic standing of one’s own countrymen, any more than it is wrong to be more concerned about the employment prospects of one’s siblings than about those of a stranger. Nor is it wrong to slow or regulate immigration in a way aimed at facilitating the assimilation of newcomers. On the contrary, as Aquinas argued (Summa Theologiae I-II.105.3), a country has the right to make sure that newcomers “have the common good firmly at heart” before being given full rights of citizenship. It is true that the vice of excess where patriotism is concerned can make one excessively hostile to immigration, but it is no less true that the vice of deficiency can make one insufficiently cautious about immigration.

Again, the need to avoid one extreme does not justify going to the other. It requires holding to the sober – patriotic – middle ground.

Related posts:

John Paul II in defense of the nation and patriotism

Liberty, equality, fraternity?

Published on July 04, 2020 16:55

June 30, 2020

The popes against the revolution

The Church has consistently condemned doctrinaire laissez-faireforms of capitalism and insisted on just wages, moderate state intervention in the economy, and the grave duty of the rich to assist the poor. Everyone knows these things because they are frequently talked about, and rightly so. But the Church has also consistently and vigorously opposed socialism in all its forms and all left-wing revolutionary movements, for reasons grounded in natural law and Christian moral theology. This is less frequently talked about, but especially important today, when much of what is being done or called for in the name of justice is in fact gravely immoral. Here are some relevant statements from popes of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, organized by topic. I have selected them from this time period because the material conditions of the poor were worse then than they are today, and yet the popes still condemned extremist revolutionary measures in the strongest terms. What was true then is a fortiori true now. To churchmen who are wondering how to respond to the current crisis: Here are your models, and here are your principles.

The Church has consistently condemned doctrinaire laissez-faireforms of capitalism and insisted on just wages, moderate state intervention in the economy, and the grave duty of the rich to assist the poor. Everyone knows these things because they are frequently talked about, and rightly so. But the Church has also consistently and vigorously opposed socialism in all its forms and all left-wing revolutionary movements, for reasons grounded in natural law and Christian moral theology. This is less frequently talked about, but especially important today, when much of what is being done or called for in the name of justice is in fact gravely immoral. Here are some relevant statements from popes of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, organized by topic. I have selected them from this time period because the material conditions of the poor were worse then than they are today, and yet the popes still condemned extremist revolutionary measures in the strongest terms. What was true then is a fortiori true now. To churchmen who are wondering how to respond to the current crisis: Here are your models, and here are your principles.The Church condemns anarchism and socialist revolution

[A] deadly plague… is creeping into the very fibres of human society and leading it on to the verge of destruction… We speak of that sect of men who, under various and almost barbarous names, are called socialists, communists, or nihilists, and who, spread over all the world, and bound together by the closest ties in a wicked confederacy, no longer seek the shelter of secret meetings, but, openly and boldly marching forth in the light of day, strive to bring to a head what they have long been planning – the overthrow of all civil society whatsoever. (Leo XIII, Quod Apostolici Muneris 1)

[T]he most disastrous national upheavals are threatening us from the growing power of the socialistic movement. They have insidiously worked their way into the very heart of the community, and in the darkness of their secret gatherings, and in the open light of day, in their writings and their harangues, they are urging the masses onward to sedition; they fling aside religious discipline; they scorn duties; they clamor only for rights; they are working incessantly on the multitudes of the needy which daily grow greater, and which, because of their poverty are easily deluded and led into error...

There remains one thing upon which We desire to insist very strongly… [for] all those who are devoting themselves to the cause of the people… That is to inculcate in the minds of the people, in a brotherly way and whenever the opportunity presents itself, the following principles; viz.: to keep aloof on all occasions from seditious acts and seditious men; to hold inviolate the rights of others; to show a proper respect to superiors. (Leo XIII, Graves de Communi Re 21, 25)

The Roman Pontiffs are to be regarded as having greatly served the public good, for they have ever endeavored to break the turbulent and restless spirit of innovators, and have often warned men of the danger they are to civil society…

Strive with all possible care to make men understand and show forth in their lives what the Catholic Church teaches on government and the duty of obedience. Let the people be frequently urged by your authority and teaching to fly from the forbidden sects, to abhor all conspiracy, to have nothing to do with sedition, and let them understand that they who for God's sake obey their rulers render a reasonable service and a generous obedience. (Leo XIII, Diuturnum Illud 25, 27)

Imperfection in social institutions does not justify sedition

And if at any time it happen that the power of the State is rashly and tyrannically wielded by princes, the teaching of the Catholic church does not allow an insurrection on private authority against them, lest public order be only the more disturbed, and lest society take greater hurt therefrom. (Leo XIII, Quod Apostolici Muneris 7)

The pastors of souls, after the example of the Apostle Paul, were accustomed to teach the people with the utmost care and diligence “to be subject to princes and powers, to obey at a word,” and to pray God for all men and particularly “for kings and all that are in a high station: for this is good and acceptable in the sight of God our Saviour.” And the Christians of old left the most striking proofs of this; for, when they were harassed in a very unjust and cruel way by pagan emperors, they nevertheless at no time omitted to conduct themselves obediently and submissively…

Christians at that period were not only in the habit of obeying the laws, but in every office they of their own accord did more, and more perfectly, than they were required to do by the laws. (Leo XIII, Diuturnum Illud 18-19)

Riots and disorder are evil and must be suppressed by the state

Among these duties the following concern the poor and the workers: … not in any way to injure the property or to harm the person of employers; in protecting their own interests, to refrain from violence and never to engage in rioting; not to associate with vicious men who craftily hold out exaggerated hopes and make huge promises, a course usually ending in vain regrets and in the destruction of wealth…

Nevertheless, not a few individuals are found who, imbued with evil ideas and eager for revolution, use every means to stir up disorder and incite to violence. The authority of the State, therefore, should intervene and, by putting restraint upon such disturbers, protect the morals of workers from their corrupting arts and lawful owners from the danger of spoliation. (Leo XIII, Rerum Novarum 30, 55)

By means of false promises a people is deceived and provoked to hatred, rivalry and rebellion, especially when the hereditary faith, the only relief in this earthly exile, is successfully torn from its heart. Disturbances, riots and revolts are organized and fomented in continuing series, which prepare for the ruin of the economy and cause irreparable harm to the common good. (Pius XII, Anni Sacri 4)

It is evil to pit classes and races against one another

It is a capital evil with respect to the question We are discussing to take for granted that the one class of society is of itself hostile to the other, as if nature had set rich and poor against each other to fight fiercely in implacable war. This is so abhorrent to reason and truth that the exact opposite is true; for just as in the human body the different members harmonize with one another, whence arises that disposition of parts and proportion in the human figure rightly called symmetry, so likewise nature has commanded in the case of the State that the two classes mentioned should agree harmoniously and should properly form equally balanced counterparts to each other. Each needs the other completely…

At the realization of these things the proud spirit of the rich is easily brought down, and the downcast heart of the afflicted is lifted up; the former are moved toward kindness, the latter toward reasonableness in their demands. Thus the distance between the classes which pride seeks is reduced, and it will easily be brought to pass that the two classes, with hands clasped in friendship, will be united in heart.

Yet, if they obey Christian teachings, not merely friendship but brotherly love also will bind them to each other. They will feel and understand that all men indeed have been created by God, their common Father. (Leo XIII, Rerum Novarum 28, 37-38)

The Christian law of charity… embraces all men, irrespective of ranks, as members of one and the same family, children of the same most beneficent Father, redeemed by the same Saviour, and called to the same eternal heritage. (Leo XIII, Graves de Communi Re 8)

[B]eing as it were compacted and fitly joined together in one body, we should love one another, with a love like that which one member bears to another in the same body…

But in reality never was there less brotherly activity amongst men than at the present moment. Race hatred has reached its climax; peoples are more divided by jealousies than by frontiers; within one and the same nation, within the same city there rages the burning envy of class against class…

When the twofold principle of cohesion of the whole body of society has been weakened, that is to say, the union of the members with one another by mutual charity and their union with their head by their dutiful recognition of authority, is it to be wondered at, Venerable Brethren, that human society should be seen to be divided as it were into two hostile armies bitterly and ceaselessly at strife?... And so the poor who strive against the rich as though they had taken part of the goods of others, not merely act contrary to justice and charity, but also act irrationally, particularly as they themselves by honest industry can improve their fortunes if they choose. It is not necessary to enumerate the many consequences, not less disastrous for the individual than for the community, which follow from this class hatred. We all see and deplore the frequency of strikes, which suddenly interrupt the course of city and of national life in their most necessary functions, we see hostile gatherings and tumultous crowds, and it not unfrequently happens that weapons are used and human blood is spilled. (Benedict XV, Ad Beatissimi Apostolorum 7, 12)

The unity of human society cannot be founded on an opposition of classes. (Pius XI, Quadragesimo Anno 88)

Race must not become an idol

Whoever exalts race, or the people, or the State, or a particular form of State, or the depositories of power, or any other fundamental value of the human community – however necessary and honorable be their function in worldly things – whoever raises these notions above their standard value and divinizes them to an idolatrous level, distorts and perverts an order of the world planned and created by God; he is far from the true faith in God and from the concept of life which that faith upholds. (Pius XI, Mit Brennender Sorge 7)

Socialism and communism are intrinsically evil

In addition to injustice, it is only too evident what an upset and disturbance there would be in all classes [under socialism], and to how intolerable and hateful a slavery citizens would be subjected. The door would be thrown open to envy, to mutual invective, and to discord; the sources of wealth themselves would run dry, for no one would have any interest in exerting his talents or his industry; and that ideal equality about which they entertain pleasant dreams would be in reality the levelling down of all to a like condition of misery and degradation. Hence, it is clear that the main tenet of socialism, community of goods, must be utterly rejected, since it only injures those whom it would seem meant to benefit, is directly contrary to the natural rights of mankind, and would introduce confusion and disorder into the commonweal. The first and most fundamental principle, therefore, if one would undertake to alleviate the condition of the masses, must be the inviolability of private property. (Leo XIII, Rerum Novarum 15)

Social Democracy… with due consideration to the greater or less intemperance of its utterance, is carried to such an excess by many as to maintain that there is really nothing existing above the natural order of things, and that the acquirement and enjoyment of corporal and external goods constitute man's happiness. It aims at putting all government in the hands of the masses, reducing all ranks to the same level, abolishing all distinction of class, and finally introducing community of goods. Hence, the right to own private property is to be abrogated, and whatever property a man possesses, or whatever means of livelihood he has, is to be common to all…

It is clear, therefore, that there in nothing in common between Social and Christian Democracy. They differ from each other as much as the sect of socialism differs from the profession of Christianity. (Leo XIII, Graves de Communi Re 5-6)

Whether considered as a doctrine, or an historical fact, or a movement, Socialism, if it remains truly Socialism, even after it has yielded to truth and justice on the points which we have mentioned, cannot be reconciled with the teachings of the Catholic Church because its concept of society itself is utterly foreign to Christian truth…

If Socialism, like all errors, contains some truth (which, moreover, the Supreme Pontiffs have never denied), it is based nevertheless on a theory of human society peculiar to itself and irreconcilable with true Christianity. Religious socialism, Christian socialism, are contradictory terms; no one can be at the same time a good Catholic and a true socialist. (Pius XI, Quadragesimo Anno 117, 120)

Communism is intrinsically wrong, and no one who would save Christian civilization may collaborate with it in any undertaking whatsoever. Those who permit themselves to be deceived into lending their aid towards the triumph of Communism in their own country, will be the first to fall victims of their error. And the greater the antiquity and grandeur of the Christian civilization in the regions where Communism successfully penetrates, so much more devastating will be the hatred displayed by the godless. (Pius XI, Divini Redemptoris 58)

The Church has condemned the various forms of Marxist Socialism; and she condemns them again today, because it is her permanent right and duty to safeguard men from fallacious arguments and subversive influence that jeopardize their eternal salvation. (Pius XII, Evangelii Praecones 52)

Regulated capitalism is not intrinsically unjust

The Encyclical of Our Predecessor of happy memory had in view chiefly that economic system, wherein, generally, some provide capital while others provide labor for a joint economic activity…

With all his energy Leo XIII sought to adjust this economic system according to the norms of right order; hence, it is evident that this system is not to be condemned in itself. And surely it is not of its own nature vicious…

Those who are engaged in producing goods, therefore, are not forbidden to increase their fortune in a just and lawful manner; for it is only fair that he who renders service to the community and makes it richer should also, through the increased wealth of the community, be made richer himself according to his position. (Pius XI, Quadragesimo Anno 100, 136)

The nuclear family must be defended against socialism

Inasmuch as the domestic household is antecedent, as well in idea as in fact, to the gathering of men into a community, the family must necessarily have rights and duties which are prior to those of the community, and founded more immediately in nature…

The contention, then, that the civil government should at its option intrude into and exercise intimate control over the family and the household is a great and pernicious error… Paternal authority can be neither abolished nor absorbed by the State; for it has the same source as human life itself… The socialists, therefore, in setting aside the parent and setting up a State supervision, act against natural justice, and destroy the structure of the home. (Leo XIII, Rerum Novarum 13-14)

The foundation of this society rests first of all in the indissoluble union of man and wife according to the necessity of natural law, and is completed in the mutual rights and duties of parents and children... You know also that the doctrines of socialism strive almost completely to dissolve this union; since, that stability which is imparted to it by religious wedlock being lost, it follows that the power of the father over his own children, and the duties of the children toward their parents, must be greatly weakened. (Leo XIII, Quod Apostolici Muneris 8)

Communism is particularly characterized by the rejection of any link that binds woman to the family and the home, and her emancipation is proclaimed as a basic principle. She is withdrawn from the family and the care of her children, to be thrust instead into public life and collective production under the same conditions as man. The care of home and children then devolves upon the collectivity. Finally, the right of education is denied to parents, for it is conceived as the exclusive prerogative of the community, in whose name and by whose mandate alone parents may exercise this right. (Pius XI, Divini Redemptoris 11)

Stable families and sexual restraint are a necessary precondition of social order

Truly, it is hardly possible to describe how great are the evils that flow from divorce. Matrimonial contracts are by it made variable; mutual kindness is weakened; deplorable inducements to unfaithfulness are supplied; harm is done to the education and training of children; occasion is afforded for the breaking up of homes; the seeds of dissension are sown among families; the dignity of womanhood is lessened and brought low, and women run the risk of being deserted after having ministered to the pleasures of men. Since, then, nothing has such power to lay waste families and destroy the mainstay of kingdoms as the corruption of morals, it is easily seen that divorces are in the highest degree hostile to the prosperity of families and States, springing as they do from the depraved morals of the people, and, as experience shows us, opening out a way to every kind of evil-doing in public and in private life. (Leo XIII, Arcanum 29)

Those who have the care of the State and of the public good cannot neglect the needs of married people and their families, without bringing great harm upon the State and on the common welfare…

But not only in regard to temporal goods, Venerable Brethren, is it the concern of the public authority to make proper provision for matrimony and the family, but also in other things which concern the good of souls. Just laws must be made for the protection of chastity, for reciprocal conjugal aid, and for similar purposes, and these must be faithfully enforced, because, as history testifies, the prosperity of the State and the temporal happiness of its citizens cannot remain safe and sound where the foundation on which they are established, which is the moral order, is weakened and where the very fountainhead from which the State draws its life, namely, wedlock and the family, is obstructed by the vices of its citizens. (Pius XI, Casti Connubii 121-123)

Police protection and punishment of criminals are necessary for social order

A peaceful and ordered social life, whether within a national community or in the society of nations, is only possible if the juridical norms which regulate the living and working together of the members of the society are observed. But there are always to be found people who will not keep to these norms and who violate the law. Against them society must protect itself. Hence derives penal law, which punishes the transgression and, by inflicting punishment, leads the transgressor back to the observance of the law violated…

If what We have just said holds good in normal times, its urgency is particularly evident in time of war or of violent political disturbances, when civil strife breaks out within a state. The offender in political matters upsets the order of social life just as much as the offender in common law: to neither must be allowed assurance of impunity in his crime. (Pius XII, “Address to the Sixth International Congress of Penal Law”)

The punishment is the reaction, required by law and justice, to the crime: they are like a blow and a counter-blow. The order violated by the criminal act demands the restoration and re-establishment of the equilibrium which has been disturbed…

Sacred Scripture (Romans xiii , 2–4) teaches that human authority, within its own limits, is, when there is question of inflicting punishment, nothing else than the minister of divine justice. “For he is God’s minister: an avenger to execute wrath upon him that doth evil.” (Pius XII, “Discourse to the Catholic Jurists of Italy”)

Destruction of cultural artifacts is a common tactic of communists

Where Communism has been able to assert its power… it has striven by every possible means, as its champions openly boast, to destroy Christian civilization and the Christian religion by banishing every remembrance of them from the hearts of men, especially of the young…

Not only this or that church or isolated monastery was sacked, but as far as possible every church and every monastery was destroyed. Every vestige of the Christian religion was eradicated, even though intimately linked with the rarest monuments of art and science. (Pius XI, Divini Redemptoris 19-20)

Disguising their true goals is a common tactic of socialists

Although the socialists, stealing the very Gospel itself with a view to deceive more easily the unwary, have been accustomed to distort it so as to suit their own purposes, nevertheless so great is the difference between their depraved teachings and the most pure doctrine of Christ that none greater could exist. (Leo XIII, Quod Apostlici Muneris 5)

In the beginning Communism showed itself for what it was in all its perversity; but very soon it realized that it was thus alienating the people. It has therefore changed its tactics, and strives to entice the multitudes by trickery of various forms, hiding its real designs behind ideas that in themselves are good and attractive. Thus, aware of the universal desire for peace, the leaders of Communism pretend to be the most zealous promoters and propagandists in the movement for world amity. Yet at the same time they stir up a class-warfare which causes rivers of blood to flow... [W]ithout receding an inch from their subversive principles, they invite Catholics to collaborate with them in the realm of so-called humanitarianism and charity; and at times even make proposals that are in perfect harmony with the Christian spirit and the doctrine of the Church… See to it, Venerable Brethren, that the Faithful do not allow themselves to be deceived! (Pius XI, Divini Redemptoris 57-58)

The Church honors Columbus, despite his flaws

For [Columbus’s] exploit is in itself the highest and grandest which any age has ever seen accomplished by man; and he who achieved it, for the greatness of his mind and heart, can be compared to but few in the history of humanity. By his toil another world emerged from the unsearched bosom of the ocean: … greatest of all, by the acquisition of those blessings of which Jesus Christ is the author, they have been recalled from destruction to eternal life…

We consider that this immortal achievement should be recalled by Us with memorial words. For Columbus is ours… it is indubitable that the Catholic faith was the strongest motive for the inception and prosecution of the design; so that for this reason also the whole human race owes not a little to the Church…

We say not that he was unmoved by perfectly honourable aspirations after knowledge, and deserving well of human society; nor did he despise glory, which is a most engrossing ideal to great souls; nor did he altogether scorn a hope of advantages to himself; but to him far before all these human considerations was the consideration of his ancient faith... This view and aim is known to have possessed his mind above all; namely, to open a way for the Gospel over new lands and seas…

It is fitting that we should confess and celebrate in an especial manner the will and designs of the Eternal Wisdom, under whose guidance the discoverer of the New World placed himself with a devotion so touching.

In order, therefore, that the commemoration of Columbus may be worthily observed, religion must give her assistance to the secular ceremonies. And as at the time of the first news of the discovery public thanksgiving was offered by the command of the Sovereign Pontiff to Almighty God, so now we have resolved to act in like manner in celebrating the anniversary of this auspicious event. (Leo XIII, Quarto Abeunte Saeculo 1-3, 7-8)

No completely secular solution of social problems is possible

Human society in its civil aspects was renewed fundamentally by Christian institutions… Wherefore, if human society is to be healed, only a return to Christian life and institutions will heal it. In the case of decaying societies it is most correctly prescribed that, if they wish to be regenerated, they must be recalled to their origins. For the perfection of all associations is this, namely, to work for and to attain the purpose for which they were formed, so that all social actions should be inspired by the same principle which brought the society itself into being. Wherefore, turning away from the original purpose is corruption, while going back to this discovery is recovery…

The Church… provided aid for the wretched poor. For, as the common parent of rich and poor, with charity everywhere stimulated to the highest degree, she founded religious societies and numerous other useful bodies, so that, with the aid which these furnished, there was scarcely any form of human misery that went uncared for.

And yet many today go so far as to condemn the Church as the ancient pagans once did, for such outstanding charity, and would substitute in lieu thereof a system of benevolence established by the laws of the State. But no human devices can ever be found to supplant Christian charity, which gives itself entirely for the benefit of others…

Since religion alone, as We said in the beginning, can remove the evil, root and branch, let all reflect upon this: First and foremost Christian morals must be reestablished, without which even the weapons of prudence, which are considered especially effective, will be of no avail, to secure well-being. (Leo XIII, Rerum Novarum 41, 44-45, 82)

Christianity, not revolution, is the true liberator of peoples

Being greatly moved by the deplorable condition of the Indians in Lower America, our illustrious predecessor Benedict XIV pleaded their cause, as you are aware, in most weighty words… [T]he worst of these indignities – that is to say, slavery, properly so called – was, by the goodness of the merciful God, abolished; and to this public abolition of slavery in Brazil and in other regions the excellent men who governed those Republics were greatly moved and encouraged by the maternal care and insistence of the Church. (St. Pius X, Lacrimabili Statu 1)

Let not these priests be misled, in the maze of current opinions, by the miracles of a false democracy. Let them not borrow from the rhetoric of the worst enemies of the Church and of the people, the high-flown phrases, full of promises; which are as high-sounding as unattainable… Indeed, the true friends of the people are neither revolutionaries, nor innovators: they are traditionalists. (St. Pius X, Notre Charge Apostolique 44)

It was Christianity that first affirmed the real and universal brotherhood of all men of whatever race and condition. This doctrine she proclaimed by a method, and with an amplitude and conviction, unknown to preceding centuries; and with it she potently contributed to the abolition of slavery. Not bloody revolution, but the inner force of her teaching made the proud Roman matron see in her slave a sister in Christ. (Pius XI, Divini Redemptoris 36)

Published on June 30, 2020 17:48

June 25, 2020

ACPQ symposium on Aristotle’s Revenge

The American Catholic Philosophical Association meeting in Minneapolis last November hosted an Author Meets Critics session on my book

Aristotle’s Revenge: The Metaphysical Foundations of Physical and Biological Science

. The proceedings have now been published in the Summer 2020 issue of the American Catholic Philosophical Quarterly. In the first essay I provide a précis of the book. In the second essay, philosopher Robert Koons addresses what I say in the book about the A-theory and B-theory of time, and argues that the latter is easier to reconcile with an Aristotelian philosophy of nature than I suggest. In the third essay, physicist Stephen Barr puts forward some criticisms of my views about method, space, and substantial form. In the final essay, I respond to Koons and Barr.

The American Catholic Philosophical Association meeting in Minneapolis last November hosted an Author Meets Critics session on my book

Aristotle’s Revenge: The Metaphysical Foundations of Physical and Biological Science

. The proceedings have now been published in the Summer 2020 issue of the American Catholic Philosophical Quarterly. In the first essay I provide a précis of the book. In the second essay, philosopher Robert Koons addresses what I say in the book about the A-theory and B-theory of time, and argues that the latter is easier to reconcile with an Aristotelian philosophy of nature than I suggest. In the third essay, physicist Stephen Barr puts forward some criticisms of my views about method, space, and substantial form. In the final essay, I respond to Koons and Barr.

Published on June 25, 2020 09:16

June 22, 2020

Envy cancels justice

Envy is often mistaken for anger at injustice, because both can issue in hatred. But the hatred that issues from a desire for justice is righteous, whereas the hatred that issues from envy is wicked. How can we know the difference? One telltale sign is the object of one’s hatred. Is it what a person does? Or the person himself? Aquinas writes:

Envy is often mistaken for anger at injustice, because both can issue in hatred. But the hatred that issues from a desire for justice is righteous, whereas the hatred that issues from envy is wicked. How can we know the difference? One telltale sign is the object of one’s hatred. Is it what a person does? Or the person himself? Aquinas writes:It is lawful to hate the sin in one's brother, and whatever pertains to the defect of Divine justice, but we cannot hate our brother's nature and grace without sin. Now it is part of our love for our brother that we hate the fault and the lack of good in him, since desire for another’s good is equivalent to hatred of his evil. Consequently the hatred of one's brother, if we consider it simply, is always sinful. (Summa theologiae II-II.34.3) Morally legitimate hatred is always grounded in love. One loves both justice and one’s brethren, and thus hates and seeks to correct any injustice that harms both the social order and the brother committing the injustice. If one hates one’s brother himself, the hatred is evil.

Now, it is not merely human beings in the abstract to whom we owe love. The virtue of piety requires that we have a special love for certain others. Aquinas writes:

Man becomes a debtor to other men in various ways, according to their various excellence and the various benefits received from them. On both counts God holds first place, for He is supremely excellent, and is for us the first principle of being and government. On the second place, the principles of our being and government are our parents and our country, that have given us birth and nourishment. Consequently man is debtor chiefly to his parents and his country, after God. Wherefore just as it belongs to religion to give worship to God, so does it belong to piety, in the second place, to give worship to one's parents and one's country.

The worship due to our parents includes the worship given to all our kindred, since our kinsfolk are those who descend from the same parents… The worship given to our country includes homage to all our fellow-citizens and to all the friends of our country. Therefore piety extends chiefly to these. (Summa theologiae II-II.101.1)

(Obviously, Aquinas is using “worship” here in a broad and archaic sense that entails merely the showing of due respect. He is not talking about “worshipping” parents or country in the way that we worship God, but rather in the sense of showing respect for them.)

So, just as hatred of injustice is legitimate when we see injustice in our brother, so too can it be legitimate when we see it in our parents, family, fellow citizens, or country. But hatred of parents, family, fellow citizens, or country themselves(and, even more, of God) is evil. Indeed, these kinds of hatreds are especiallyevil, given the special duty of piety we owe toward these others. These hatreds are themselves further instances of injustice, as well as sins against charity.

Of course, hatred of a person, or of parents, country, etc. can be the byproduct of something other than envy, such as an overreaction to injustice. But that is not usually the case, and even when it is, such an overreaction can morph into envy. Aquinas again:

Hatred may arise both from anger and from envy. However it arises more directly from envy, which looks upon the very good of our neighbor as displeasing and therefore hateful, whereas hatred arises from anger by way of increase. For at first, through anger, we desire our neighbor's evil according to a certain measure, that is in so far as that evil has the aspect of vengeance: but afterwards, through the continuance of anger, man goes so far as absolutely to desire his neighbor's evil, which desire is part of hatred. (Summa theologiae II-II.34.6)

In other words, even when anger starts out as a legitimate desire to punish injustice (which is what Aquinas means by “vengeance” – which, as he uses that term, is a good thing) it can, if the anger gets out of control, mutate into a desire to harm the person, to act contrary to what is good for him. That is hatred of a wicked kind, and it bears the chief mark of envy. Thus, as Aquinas writes in the same place, “envy of our neighbor is the mother of hatred of our neighbor.”

What is envy? People often confuse it with jealousy, the desire to preserve what one has or to acquire for oneself a good of the kind that another has. Jealousy in that sense is not wrong. If Bob is worried about losing his job or his wife to Fred (where Fred is trying to take these things from him), there is no sin in that. Far from it. Or, if Fred has a wife and a job and Bob, having neither, wishes he had a wife and a job too, there is no sin in that either, and in particular no envy. Envy would be present only if Bob wants Fred not to have these things either, because Fred’s having them is perceived as an affront to Bob’s self-respect.

As Aquinas says, with envy, “another's good [is] reckoned as being one's own evil, in so far as it conduces to the lessening of one's own good name or excellence” (Summa Theologiae II-II.36.1). The envious person ties his own self-respect to taking away from others the good that the envious person himself does not have. Hence, unlike legitimate anger at injustice, which abates when the unjust person shows contrition, envy is not satisfied with anything but the destruction of the person who is its object. “The envious have no pity” (II-II.36.3).

Envy is a capital sin (Summa Theologiae II-II.36.4). That is to say, it tends to have as a natural byproduct various other specific sins. First, envy seeks to defameanother, to lower his reputation in other people’s eyes. Second, envy takes joy in the harm thereby suffered by the person who is its object (or takes sorrow in whatever goodthe person in question still possesses). Third, and again, there is hatred of the person himself (and not just hatred of what he does or of the fact that he unjustly has a certain good).

Here is how we know, then, whether we are dealing with righteous anger or envy: Righteous anger is directed primarily at actions, envy is directed primarily at people. Righteous anger can be abated, envy is pitiless. Righteous anger seeks to restore the right order of things, envy seeks to tear down, especially by defamation. Righteous anger evinces love of one’s brother, parents, fellow citizens, country, or God, whereas envy evinces hatred of one or more of these. Righteous anger can be motivated by charity and piety, but envy is contrary to these virtues.

It is righteous anger we see expressed in grand documents like Frederick Douglass’s “What to a Slave is the Fourth of July?,” which attacks the injustice of slavery, and Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” which attacks the injustice of segregation. Douglass and King are very hard on the people they are criticizing, and rightly so. But they evince no hatred at all for the people themselves, nor for their country. Rather, they call on their countrymen consistently to apply ideals they all share, namely those of the Declaration and Constitution. They seek, not to harm anyone, but rather to secure justice for those who are being harmed. They deliver stern and well-deserved moral criticism, but criticism that is magnanimous, appeals to reason, and is aimed at restoring fellowship with the people they are criticizing.

Some of what is going on around us today is also motivated by righteous anger at injustice. But some of it is clearly motivated by envy and its daughters, like tares among the wheat. The “cancel culture” that aims to destroy reputations and render people unemployable, the destruction of the property and businesses of people who had nothing to do with the injustice protested against, the push to remove police protection from everyone, the insistence on defaming one’s country and one’s fellow citizens as rotten to the core, the cruel refusal of any forgiveness, the relentless resort to intimidation rather than rational argumentation – all of that evinces hatred for persons of the kind that is typical of envy. It involves grave sins against charity and piety. It merely adds injustice to injustice.

Published on June 22, 2020 14:16

June 17, 2020

Apt pupil

Justice Neil Gorsuch was a student of John Finnis, foremost proponent of the “New Natural Law Theory” (NNLT). Is that relevant to understanding the Bostock decision? It might seem not, given that NNLT thinkers like Robbie George (hereand here) and Ryan Anderson have strongly criticized Gorsuch’s reasoning.On the other hand, if you’re wondering: Where might someone learn a style of reasoning so tortuous and sophistical that it can read an implicit reference to sexual orientation and gender identity out of the word “sex” as it was understood in 1964? And contradicting his earlier position, into the bargain?

Justice Neil Gorsuch was a student of John Finnis, foremost proponent of the “New Natural Law Theory” (NNLT). Is that relevant to understanding the Bostock decision? It might seem not, given that NNLT thinkers like Robbie George (hereand here) and Ryan Anderson have strongly criticized Gorsuch’s reasoning.On the other hand, if you’re wondering: Where might someone learn a style of reasoning so tortuous and sophistical that it can read an implicit reference to sexual orientation and gender identity out of the word “sex” as it was understood in 1964? And contradicting his earlier position, into the bargain?How about from someone capable of reasoning so tortuous and sophistical that it can read a condemnation of capital punishment as intrinsically evil out of a 2,000-year-old tradition that has consistently affirmed capital punishment as intrinsically just? And despite having earlier defended capital punishment himself?

Prof. Finnis may in this case deplore the results, but he cannot disapprove of his pupil’s method: jurisprudential chutzpah, weaponized in the service of overthrowing tradition.

Published on June 17, 2020 17:50

June 13, 2020

Locke’s “transubstantiation” of the self

Locke’s agnosticism about substance led him to treat the self as essentially a bundle of attributes. Given his empiricism, he takes it that the most we can say of a substance – whether material or immaterial – is that it is a “something, I know not what” that underlies attributes. And that is too thin a conception to lend confidence to the thesis that the self qua substance can survive death and be rewarded or punished in the afterlife. What to do? Locke’s solution was to ignore substance as beside the point. What matters for Locke is that one’s consciousness, and in particular one’s memories, can carry over after the death of the body, whether or not there is a soul for them to inhere in. That’s the point of his famous “prince and cobbler” thought experiment. We’re asked to imagine a prince and a lowly cobbler each falling asleep one night and then awakening the following morning to find himself in the other’s body, Freaky Friday style (or Vice Versa style, for you Judge Reinhold fans). This is at least theoretically possible – so Locke claims – and that possibility suffices to show, he argues, that being the same person over time does not entail having the same body over time.

Locke’s agnosticism about substance led him to treat the self as essentially a bundle of attributes. Given his empiricism, he takes it that the most we can say of a substance – whether material or immaterial – is that it is a “something, I know not what” that underlies attributes. And that is too thin a conception to lend confidence to the thesis that the self qua substance can survive death and be rewarded or punished in the afterlife. What to do? Locke’s solution was to ignore substance as beside the point. What matters for Locke is that one’s consciousness, and in particular one’s memories, can carry over after the death of the body, whether or not there is a soul for them to inhere in. That’s the point of his famous “prince and cobbler” thought experiment. We’re asked to imagine a prince and a lowly cobbler each falling asleep one night and then awakening the following morning to find himself in the other’s body, Freaky Friday style (or Vice Versa style, for you Judge Reinhold fans). This is at least theoretically possible – so Locke claims – and that possibility suffices to show, he argues, that being the same person over time does not entail having the same body over time.But neither, he thinks, does it entail having the same soul over time. For just as your consciousness can jump from body to body, so too, he argues, could it jump from soul to soul. He famously suggests that, for all you know, the soul that currently underlies your consciousness might once have belonged to Socrates. If the contents of your consciousness are like pins, then substance is like the pincushion in which they inhere. Now they are in this material pincushion (the prince’s body), now in another (the cobbler’s). Now they are in this immaterial pincushion (the soul you had yesterday), now they are in another (the soul Socrates was using centuries ago). But really, it is only the pins that matter. They, as a bundle, are you, and it doesn’t matter what pincushion, or even what kind of pincushion, they happen to be stuck in at any particular moment.

Coupled with the thesis that the mind is a kind of software, we have the basis for all those familiar thought experiments from science fiction – and, more recently, from pop “science” of the “transhumanist” sort – about people’s minds being downloaded into new bodies or uploaded into virtual reality worlds, puzzles about what would happen if a teleportation accident led to it being downloaded into two new bodies, and other gee-whiz head scratchers.

It’s all complete nonsense. For one thing, the mind is not software, though that’s not my topic here. For another, Locke’s thinking is completely muddled. (Par for the course with Locke.)

To see what’s wrong with it, consider a parallel example. Consider two bananas, which we’ll label A and B. On Monday night, A is dark green and B is bright yellow. Tuesday morning, lo and behold, A has exactly the same bright yellow appearance that B had had the night before, and B has exactly the same dark green appearance that A had had the night before. What would we say if this happened?

We might suppose that something had rapidly sped up the ripening process in A and somehow reversed it in B. We might suppose something even weirder had happened, and that the color of each banana had changed for some reason having nothing to do with the ripening process – maybe somebody injected something into each banana in order to change its color, or maybe radiation had affected them in some way, or whatever.

Here’s what I think no one would say: “Maybe the greenness of A somehow jumped into B overnight, and the yellowness of B somehow jumped into A overnight!” I also don’t think that the sequel would be to propose scenarios where the greenness jumps into two different bananas, leaving us with a “puzzle” of which, if either, is identical with the original greenness possessed by B. Nor would a “problem of banana identity” industry arise in academic philosophy to supplement the thriving “problem of personal identity” industry that Locke got started. (Though I’ll be the first to admit that you never really can know for sure these days.)

The reason is obvious. It simply makes no sense to think of the greenness of B jumping around from substance to substance. Attributessimply don’t do that sort of thing. Substances do, because they have a kind of freestanding existence that attributes do not. That’s why you can throw a banana across the room, but you can’t throw the greenness of the banana across the room. If you couldthrow the greenness across the room, then it would be a kind of substance after all. By the same token, if it could jump from banana A to banana B, it would be a kind of substance after all, and not really an attribute.

But the same thing is true of the memories and other mental phenomena Locke imagines jumping from body to body and soul to soul. They are attributes, and so they can’t jump from body to body or soul to soul. End of story, before it begins. If your shoe repairman starts talking like Chris Sarandon in The Princess Bride and demands to be known as “The Cobbler Formerly Known as Prince,” you can be sure that what has not happened is that Prince Humperdinck’s mind has entered his body. Though you can be sure that he’s nevertheless lost his own mind. He’s suffering from some kind of mental illness, that’s all. Maybe through some preternatural or science fiction-like means, information from the prince’s brain has even made its way into his brain and generated the illusion of a mind-transfer. But an illusion is all it would be, just as it would merely be an illusion if you thought that the greenness of banana A (that very greenness, and not just something similarto it) had literally made its way into banana B.

In effect, Locke really makes of mental attributes something like a bundle of little substances, so that they can jump from the prince to the cobbler and vice versa. Which makes the whole thought experiment pointless as well as muddled, since the aim was to avoid having to talk about substance.

But what about transubstantiation? Isn’t that like what Locke is talking about? Don’t we have, for example, the prince essentially being transubstantiated, his accidents persisting while the substance of his body is replaced by the substance of the cobbler’s body?

No, we don’t. In transubstantiation, the accidents of bread and wine persist, but they do not inherein the body and blood of Christ or in any other substance. They float free of substance. This is not possible in the natural order of things, of course, but that’s precisely why transubstantiation is supernatural, possible only by way of a miraculous suspension of the natural order.

Now, Locke evidently thinks of the memories and other mental characteristics of the prince as indeed actually coming to inherein the body of the cobbler (or perhaps in the cobbler’s soul – part of the point of Locke’s theory is to avoid having to say which). So, this is not the same as transubstantiation, in the theological sense of that term.

But couldn’t Locke just say that maybe the memories and other mental characteristics don’t after all inhere in any substance, so that transubstantiation might serve as a model for what he has in mind? No. Locke is trying to tell us what the natureof a person is. The proposal in question would make persons entirely supernatural, without any underlying nature for the “super” to build on. And that makes no sense. We can make sense of the accidents of bread and wine only as accidents of bread and wine, of some underlying substance, at least in the natural course of things. There’s already a natural order there that God can go on to suspend when transubstantiation occurs. He sustains the accidents apart from the natural underlying basis that gives them their identity conditions and makes them otherwise intelligible.

To say that memories and other mental characteristics are accidents that never naturally inhere in any substance would make them unintelligible. If their natural home is not any kind of substance, then in what sense are they accidents? Once again, they would end up being little substances in their own right.

Published on June 13, 2020 19:09

June 12, 2020

Great minds on wokeness

If you want to understand woke totalitarianism, I recommend reading Plato on democracy, Aristotle and Aquinas on envy, and Nietzsche on ressentiment.

If you want to understand woke totalitarianism, I recommend reading Plato on democracy, Aristotle and Aquinas on envy, and Nietzsche on ressentiment.Or you could just watch a few minutes of John Cleese, Seinfeld , South Park , and Family Guy . (But do it soon, before it’s all removed.)

Published on June 12, 2020 17:02

Edward Feser's Blog

- Edward Feser's profile

- 329 followers

Edward Feser isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.