Edward Feser's Blog, page 33

February 6, 2021

What is religion?

The question is notoriously controversial. Consider a definition like the following, from Bernard Wuellner’s

Dictionary of Scholastic Philosophy

:

The question is notoriously controversial. Consider a definition like the following, from Bernard Wuellner’s

Dictionary of Scholastic Philosophy

: religion, n. 1. the sum of truths and duties binding man to God. 2. personal belief and worship in relation to God. Religion includes creed, cult, and code.

By “creed,” what Wuellner has in mind is a system of doctrine. A “cult,” in this context, has to do with a system of rituals of the kind associated with worship and the like. The “code” referred to has to do with a system of moral principles. So, the definition is telling us that doctrines, rituals, and moral principles are among the key elements of religion.

Perhaps some would quibble over that part, though it seems safe to say that the best-known examples of religions all involve somedoctrinal, ritual, and moral components, even if some religions emphasize some of these more than others do. But the standard objection to this kind of definition has to do instead with the reference to God. For aren’t there religions (such as Buddhism) in which the notion of God does not feature, or is even rejected?

In light of such considerations, it is common these days to define religion more broadly so as to include non-theistic religions. The trick is to avoid defining the term so broadly that it ends up including things that aren’t really religions. The desired happy medium would be something like the following definition, from John Carlson’s Words of Wisdom: A Philosophical Dictionary for the Perennial Tradition:

Set of beliefs, relations, and activities by which people are united, or regard themselves as being united, to the realm of the transcendent (often, although not always, with a focus on Absolute Being or God).

The idea here would be that, although not all religions affirm the existence of God, they do all affirm that there is somereality transcending the material world. A view that denied any such transcendent reality (such as scientism, whether in its positivist form or its scientific realist form) would not fall under a plausible definition of “religion.” This seems reasonable enough. For example, however we spell out Buddhist notions like karma, nirvana, etc., they are probably not going to be expressible in terms acceptable to a Rudolf Carnap or an Alex Rosenberg.

Nominal or real definition?

Having said that, it doesn’t actually follow that Wuellner’s definition is wrong. For it depends in part on what kind of definition we’re looking for. Scholastic philosophers distinguish between nominal definitions and real definitions. A nominal definition aims to capture how people use a certain word, whereas a real definition aims to capture the nature of the reality that the word refers to. Hence, suppose I ask you to define “water.” I might be asking for an explanation of how the term “water” is used by English speakers – in which case you might respond that it is used to refer to the clear liquid that fills lakes and rivers, etc. But I might instead be asking about what it is to be the actual stuff, water (whether we refer to it as “water,” “Wasser,” “agua,” or whatever) – in which case you might discuss its chemical composition and the like.

Now, nominal definitions are essentially descriptive. They are trying to tell us how people do in fact use words. There may be certain normative implications to the extent that we are aiming to track actual usage. We may find out that the way we use a certain word in is contrary to currently prevailing usage, and therefore “wrong,” but if a critical mass of people start using the term this way it will end up no longer being wrong but merely an alternative usage.

Real definitions, by contrast, are essentially normative. They are not trying to capture actual usage, even when they are not in conflict with it. Again, they are trying to capture the nature or essence of the reality itself, which doesn’t change with changes in usage. And there is an objective fact of the matter about that, even if there is no objective fact of the matter about how a word (considered merely as a string of letters or phonemes) should be used. (Anti-essentialist views often rest on a fallacious conflation of real definitions and nominal ones – as if a change in the usage of words could change reality itself. In fact, the most it can do is muddle our thinking about reality.)

Now, to evaluate a definition like Wuellner’s, we’d need first to know whether he intends it as a nominal or a real definition. Considered as a nominal definition, it would indeed be defective in just the way described, since people use the term “religion” to refer to non-theistic systems of belief as well as to theistic ones.

But that is surely not how Wuellner meant it. Rather he was, as a Scholastic and a Catholic, trying to capture the objective reality behind the phenomena we call “religion.” He would probably say that in light of the fact that God exists and that we are by nature oriented to seeking and worshipping him, religion arises in various cultures as a byproduct of this natural tendency. Like everything else in nature, this tendency is subject to distortion and frustration. Sometimes our religious inclinations might be directed toward an improper object, as in idolatrous or non-theistic religions. Sometimes they may be altogether stifled, as in atheism. But the natural inclination toward God is there all the same, and should inform any attempt at a real definition of religion.

Naturally, a real definition of a phenomenon like religion is bound to be controversial. But it is not a serious objection to such a definition to point out that it doesn’t correspond exactly to actual usage. It isn’t trying to do that.

Consider another example. Marx famously said: “Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people.” Suppose this was meant as a definition of religion. I certainly think it is wrong. But it would be a stupid objection to say: “Marx, that’s not how people actually use the term. Most people don’t think of religion as analogous to a drug that enables them to deal with oppressive socioeconomic conditions.” Marx was well aware of that, of course. He was not doing lexicography, but rather what he considered to be a kind of scientific explanation of the function that religion performs in the sociopolitical order. He held that, whatever people think religion is about, the objectively true explanation of why it exists is that it helps to fortify an existing economic order by reconciling people to that order’s harsher aspects.

This is a functional explanation, just like an explanation a biologist might give of a bodily organ – and just like Wuellner’s explanation, albeit he and Marx attribute very different functions to religion (in Wuellner’s case, it functions to orient us in a certain way to God, and in Marx’s it functions to orient us in a certain way to the established economic order). And just as a biologist might appeal to an organ’s function in giving a real definition of it, Wuellner and Marx are each appealing to the function they attribute to religion in giving a real definition of it.

I think that Wuellner’s definition happens to be correct and Marx’s wrong, but that’s a separate issue. The point, again, is that we need to know what kind of definition a theorist is proposing before we can evaluate it, and that in the case of real definitions it misses the point to note that a definition doesn’t correspond exactly to actual usage.

Religions or philosophies?

But there’s another potential problem with the standard objection to definitions like Wuellner’s, even when considered as nominal rather than real definitions. For why should we count examples like Buddhism as religions in the first place? Well, everyone does so, you might say. But there’s a problem with that.

Suppose the purported counterexample raised against Wuellner’s definition was Epicureanism rather than Buddhism. That is to say, suppose the critic said: “You can’t define religion in general in terms of the worship of God or gods, because Epicureanism doesn’t feature the worship of God or gods.” A defender of the definition would no doubt respond by saying that Epicureanism is not a religion in the first place, but a philosophy, so that it isn’t a genuine counterexample.

But why not count it is a religion? After all, even if the worship of the gods doesn’t feature in it, the existence of the gods does, at least insofar as it isn’t denied. So, arguably the existence of some kind of “transcendent” realm is allowed. Of course, this particular transcendent realm doesn’t play a role in the moral life of the Epicurean, so that might be thought to justify not counting it as a religion. But now consider the example of Stoicism. Here too we have something like a transcendent reality – the divine logos or world soul – and one’s proper orientation to it does play a role in the moral life of the Stoic. Yet Stoicism too is usually classified as a philosophy rather than a religion.

Now, someone might conclude: “OK, so maybe we shouldclassify these systems as religions rather than philosophies.” But why not instead conclude that Buddhism too is not after all a religion, but rather a philosophy? True, it has aspects that usually bring to mind religion rather than philosophy, such as certain rituals. But why not just say that it is a philosophy with which certain religion-like elements have come to be associated, just as Marxism is (with its personality cults in cases like the Stalinist and Maoist versions of Marxism)?

The point is that the range of the actual use of the term “religion” seems to be somewhat arbitrary. People don’t actually apply it to a clearly demarcated set of phenomena, but rather in a way that reflects criteria that are loose at best and maybe even inconsistent. Now, sometimes with nominal definitions, when we encounter usage that is loose or inconsistent in this way, we propose a stipulative definition to tighten usage up at least for some particular purpose (as in a legal context). And you could read a definition like Wuellner’s that way. Someone could say: “Sure, we don’t use ‘religion’ to refer only to systems that feature belief in a God or gods. But then, the ordinary usage of the term is a mess anyway. I propose that we reform existing usage by tightening it up and relegating systems that don’t involve the worship of a God or gods to the ‘philosophy’ category.”

Maybe that’s a good idea, and maybe not. But the point is that the actual usage of the term “religion” is indeed messy enough that even considered as a nominal definition, a definition like Wuellner’s can’t reasonably be dismissed tooquickly on the basis of alleged counterexamples. For the counterexamples might reflect a problem with actual usage, no less than a problem with the definition.

Inventing “religion”

These problems are not surprising given the history of the usage. For as scholars of religion often point out, the category of “religion” as we understand it today is actually a modern invention. Brent Nongbri’s book Before Religion: A History of a Modern Concept is a useful study. As Nongbri points out, we tend today to think of “religion” by way of contrast with “secular” matters, as if these are two clearly demarcated spheres of human life. But that is an invention of modern Europeans, and indeed an artifact of Protestant vs. Catholic and Enlightenment-era polemic. Non-Western and pre-modern Western thinking on the subject drew no such distinction.

True, there were distinctions like the distinction between Church and State and between the spiritual and temporal realms. But those distinctions are very different from the modern “religious” versus “secular” distinction. To be sure, and as I have discussed elsewhere, the idea of Church and State as clearly demarcated institutions with distinctive functions is central to Christianity, though foreign to religions like Islam. But this was not taken to entail a separationof Church and State, any more than the fact that the soul and the body are distinct and clearly demarcated aspects of human nature entails that the body can exist in separation from the soul.

In ordinary human life, we have a variety of concerns – what to have for dinner, how to earn a living, where to send our children to school, who to vote for, how to fix a car, and so on. And we also have concerns about getting ourselves right with God, doing right by our fellow religious believers, and so on. Now, no one thinks that the fact that the concerns in the first set are very different in nature entails that there are clearly demarcated and hermetically sealed off realms like the “culinary,” the “economic,” the “educational,” the “automotive,” etc. that can or ought to be kept totally separate. No one calls for a “separation of economics and state” or a “separation of the automotive from the state.” That would, or course, be ridiculous. Yet modern Westerners pretend that the “religious” is some clearly demarcated and hermetically sealed off realm, an aspect of human life that can be (and, in the view of many, should be) conducted separately from those other aspects, which are purely “secular.” That conception of religion is, as Nongbri points out, a modern invention.

How did it arise? To understand this, we need to begin by considering the set of attitudes that Nongbri says it replaced. First, though the term “Europa” is ancient, medieval Europeans did not conceptualize themselves as “Europeans” – that is itself a modern secular category. Rather, they thought of their homeland as Christendom or as the respublica Christiana. And they didn’t speak of a variety of “world religions.” Rather, groups like Manicheans and Muslims were classified as heretics, insofar as they shared some beliefs in common with Christians but rejected others and (from the point of view of Christianity) distorted the ones they did share. And those who worshipped gods like those of Greece and Rome were classified as pagans, whose deities were in reality demons.

In other words, matters of “religion” were conceptualized from a distinctively Christian point of view. Now, Nongbri does in fact oversimplify things here. From the beginning, Christians did recognize a category of natural theology by which pagans were capable of some imperfect knowledge of the true God. All the same, he is correct to say that they took Christianity as normative, and certainly did not conceptualize it as one option alongside the others in a “world religions” smorgasbord. And the point is not that they thought of it as the best or even as the correct option. The point is that they didn’t think in terms of options at all. In particular, they didn’t think in terms of “religions,” any more than modern people think of physics, astrology, acupuncture, Star Trek lore, etc. as different possible “sciences,” with physics being the best or correct one. Rather, they thought in terms of there being (a) the truth about God and his relationship to the human race, and (b) greater or lesser deviations from this truth.

But then came Protestantism, which destroyed this unified view of the matter. And it did so not only at the intellectual level, but at a practical and political level – so much so that the sequel to the Reformation was decades of war. Thinkers like John Locke judged that a political solution to the problem of restoring peace would be to relegate theological disagreements to the realm of private opinions that ought to have no influence on public affairs, and can be safely tolerated to the extent that they are segregated from politics. And therein, Nongbri argues, lies the origin of the conceptualization of “religion” as an idiosyncratic sphere of subjective belief sealed off from the “secular.” I would add that this “subjectivizing” of religion was facilitated by a strongly fideistic strain within Protestantism that was hostile to the notions of natural law and natural theology. (See chapter 5 of my book Lockefor critical discussion of Locke’s theory of toleration.)

What happened next was that this compartmentalized conception of “religion” was projected by post-Enlightenment Westerners onto the rest of the world. Western scholars would look at, say, the ancient and complex set of philosophical ideas, devotions to various deities, moral attitudes, sociopolitical institutions, etc. to be found in India, lump them all together as if they were part of some unified system, and slap the label “Hinduism” on this imagined system. They would do the same with “Buddhism,” “Confucianism,” and so on, and then announce that these various “world religions” are all instances of some general phenomenon called “religion.” Then they would look at now defunct sets of practices and ideas of the past, lump them together, and classify them as various examples of “ancient religions,” further species of the same general phenomenon of “religion.” And again, this general phenomenon was conceived of as an idiosyncratic, subjective thing in a sphere of its own only contingently connected to politics, morality, and the rest of human life – even though the ideas and practices in question had never been understood that way, outside the imaginations of post-Protestant, post-Enlightenment Westerners.

Now, one can debate whether the demarcations of the various so-called “world religions” are actually as arbitrary as writers like Nongbri imply. I think we need to be careful not to overstate things. All the same, there is some non-trivial degree of arbitrariness here, and it is certainly arbitrary to characterize “religion” in general as some idiosyncratic and subjective sphere separable from the rest of human life, the way that modern Westerners now reflexively tend to do.

The rhetoric of “religion”

The reason this characterization survives is the same as the reason it was introduced in the first place by early modern thinkers like Locke. It serves politicaland polemical purposes. It is a rhetorical weapon by means of which certain ideas can be put at a political and/or intellectual disadvantage right out of the gate.

Think, for example, of the double standard that many contemporary academic philosophers apply to arguments for God’s existence. Any other idea in philosophy, no matter how insane – for example, that the material world is an illusion, that consciousness does not really exist, that infanticide and euthanasia are defensible, that the distinction between the sexes is a mere social construct, that it might be morally wrong to have children, and so on and on – is treated as “worthy of discussion,” something we must at least hear out with respect even if we suspect we will not be convinced. But if a philosopher gives an argument for God’s existence, then in at least many academic circles, every eyebrow is immediately raised, every eye rolls, and it’s smirks all around – as if such a philosopher had just passed gas, or proposed wearing a tinfoil hat to protect against mindreading.

This is, historically speaking, extremely odd and idiosyncratic. In first-rate thinkers like Plato, Aristotle, Plotinus, Augustine, Avicenna, Anselm, Al-Ghazali, Maimonides, Aquinas, Scotus, Suarez, Descartes, Leibniz, Clarke, et al. one finds arguments for God’s existence that are no less central to their thought than any other arguments they give for conclusions of a metaphysical, epistemological, or ethical nature. There is absolutely no objective reason to treat the arguments with any less interest and respect than anything else they say. And this would have been generally acknowledged as recently as just a few decades ago. But in recent decades, those who don’t have a special interest in philosophy of religion often not only neglect such arguments, but treat them as having a second-class status to which other philosophical ideas and arguments are not consigned.

The reason for this, I would suggest, has to do with the hegemony of the modern idea that “religion” is an idiosyncratic and subjective sphere having no essential connection to the rest of human life. It leads people reflexively to be suspicious of any argument for a religious conclusion, no matter how sophisticated and subtle, as if it were “really” “nothing but” an exercise in rationalization. Hence we have the absurd situation where a philosopher can give slipshod arguments for the most morally depraved conclusions whatever, and no one is ever supposed to think: “Hmm, I guess I’ll hear it out, but you do kind of wonder if he’s trying to justify being a pervert.” But if, say, an Alex Pruss or Rob Koons presents a theistic proof, no matter how rigorously, the circumstantial ad hominem suddenly becomes a decisive refutation: “Oh come on, we all know that he’s just trying to rationalize his religious prejudices!”

Or think of the rhetorical game New Atheist types play in order to cast doubt on the rational and moral credibility of the general phenomenon of “religion.” They will lump together, as representative samples of “religion,” ideas, practices, and people as diverse as: Thomistic metaphysics, sola fide, snake handling, Zen Buddhism, jihadists, the Tridentine Mass, Gödel’s ontological proof, the Heaven’s Gate cult, the Norse gods, the six schools of Indian philosophy, Lao-Tzu, Jimmy Swaggart, Pope St. Pius X, Kirk Cameron, Deepak Chopra, Adi Shankara, Joseph Campbell, Averroes, etc. The more embarrassing things on the list are supposed to make us doubt the worthiness of the others.

But you could play this same rhetorical game with anysubject matter in order to make it look disreputable. For example, suppose we gave the following list as a representative sample of “science” and “scientists”: general relativity, phlogiston theory, caloric theory, the Periodic Table, pre-Copernican astronomy, phrenology, Lysenkoism, quantum mechanics, parapsychology, Lamarckian evolution, Darwinian evolution, Paul Dirac, Rupert Sheldrake, Alfred Wegener, Immanuel Velikovsky, etc. Suppose we kept Isaac Newton off the “science” list and put him on the “religion” list, since he wrote more about the latter topic than the former. Suppose we took Deepak Chopra off the “religion” list and put him on the “science” list, on the grounds that he uses the word “quantum” a lot. And suppose we did the same with the Heaven’s Gate cult, because they talked about comets and extraterrestrials. We could by such a tactic make science look pretty stupid to people who didn’t know much about it, just as New Atheist types are able to make religionlook stupid to people who don’t know much about it.

Hence we have a further reason why “religion” has turned out to be a difficult concept to define, which lies in the political and polemical interest some have in making the definition come out a certain way. And this interest has its roots – like so much else in modernity – in the apostate project of supplanting what once was Christendom.

January 31, 2021

Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia on soul-body interaction

The letters exchanged between Descartes and Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia – especially their 1643 exchange on the interaction problem – are among the best-known correspondences in the history of philosophy. And justly so, for they help to elucidate the true nature of that crucial problem and the inadequacy of Descartes’ response to it. Though I think that in at least one important respect, Elisabeth errs in her characterization of the issue.

The letters exchanged between Descartes and Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia – especially their 1643 exchange on the interaction problem – are among the best-known correspondences in the history of philosophy. And justly so, for they help to elucidate the true nature of that crucial problem and the inadequacy of Descartes’ response to it. Though I think that in at least one important respect, Elisabeth errs in her characterization of the issue. You can find the relevant letters in several anthologies, such as Margaret Atherton’s (which is the source from which I’ll be quoting). You can also find them online. What follows is a summary of the key points in their back-and-forth, with some comments.

Round one

Elisabeth begins by noting that if we think of efficient causation on the model of one extended object making contact with another and pushing against it (which would have been natural for those working with the then-ascendant Mechanical Philosophy’s conception of matter), then the interaction between soul and body – when conceived of in Cartesian terms – is hard to understand. For whereas Descartes takes the body to be pure extension, he takes the soul to be pure thought devoid of extension. Elisabeth suggests that clarification requires an account of the nature of the substanceof the soul, apart from its activity of thought.

Descartes responds by saying that our notions of the soul, of the body, and of the union of the two are each primitive, and that we must be careful not to attribute what is true of one of these to the others. Now, this is what happens when we try to conceive of the manner in which the soul moves the body on the model of the way in which one physical object moves another. This is, as philosophers would say today, a “category mistake,” and it seems that Descartes is implying that Elisabeth is guilty of such a mistake in formulating her puzzlement over the nature of soul-body interaction.

Descartes also suggests that such a category mistake is committed by the Aristotelians of his day who thought of physical objects as, by virtue of their weight, drawn toward the center of the earth – where it seems that it is the teleology or final causality posited by this account that he has primarily in mind. He says that this account wrongly attributes to a physical object’s relation to the earth’s center what in fact holds of the body-soul relationship. His point seems to be that while the notion of teleology has (in his view) no application in physics, it does provide us with a way of understanding how the soul acts on the body.

Descartes’ reply to Elisabeth is not entirely unhelpful. Certainly he is right to emphasize that he would not say, and is not forced by his commitments to say, that soul-body interaction is correctly modeled on efficient causation between two physical substances. However, his reply is not entirely helpful either…

Round two

In her response, Elisabeth suggests that it is not clear how the weight analogy provides a better model by which to understand how the soul moves the body. And Descartes’ explanation is indeed not entirely lucid, though one can imagine ways to develop it that Elisabeth does not consider. Presumably the analogy goes like this: On Aristotle’s model, the center of the earth is the end toward which a physical object moves by nature; and on Descartes’ model, the soul is the end toward which the body moves by nature. And though Descartes rejects the teleological account of the movement of physical objects relative to the earth, teleology does provide a way of modeling the movement of the body relative to the soul.

In any case, though Descartes himself doesn’t explicitly say all that, it seems to me to be a way of interpreting him that accounts for why he would think the weight analogy at all helpful. But immediately, problems arise. Part of the point of Descartes’ adoption of a mechanistic conception of matter was to get teleology out of it. But now he seems to be putting teleology back into matter again, at least for the purpose of solving the interaction problem if not for purposes of general physics. Isn’t this ad hoc?

Elisabeth also still regards the case of soul-to-body causation as so puzzling that she says she finds it “easier… to concede matter and extension to the soul, than the capacity of moving a body… to an immaterial being.” This is in my view her main mistake, for reasons I will explain presently. But she immediately makes another point which is correct, extremely important, and widely neglected. For it is not just the soul’s capacity for moving the body that Descartes has to explain, but also its “capacity… of being moved” by it. She continues:

It is, however, very difficult to comprehend that a soul, as you have described it, after having had the faculty and habit of reasoning well, can lose all of it on account of some vapors, and that, although it can subsist without the body and has nothing in common with it, is yet so ruled by it.

End quote. In short, whatever one thinks of soul-to-body causation, causation in the other direction – that is to say, body-to-soul causation – is really mysterious if one accepts a Cartesian account of soul and body. And the reason why it is so mysterious is, in my view, linked to the reason why soul-to-body causation is not in fact as problematic as Elisabeth thinks it is, or at least not problematic in the specific wayshe thinks it is.

But I’ll come back to all that too in a moment. First let’s consider the rest of the exchange. Descartes’ response is once again to comment on the differences between our notions of the soul, of the body, and of the union between them. He appeals to the traditional distinction between the intellect or understanding, the imagination, and the senses. He says that the soul is properly known by the understanding alone, the body by the understanding together with the imagination, and the union between them by the understanding together with the imagination and the senses.

The idea here seems to be that since the soul is, as Descartes understands it, pure thought devoid of extension, it is the abstractness of purely intellectual apprehension by which we most accurately understand it. The body qua extension, however, is best understood by the intellect together with the sort of mental imagery we entertain when doing geometry. And the closeness of the union between soul and body is evident in attributes which, in Descartes’ view, neither soul nor body can have on its own – namely, appetites, emotions, and sensations, which he takes to be hybrid attributes of a kind that exist only insofar as a res cogitansand a res extensa get into a causal relationship. Hence, Descartes seems to be saying, we need to rely on our experiences of bodily sensations, affective states, and the like – and not just on intellect and imagination – properly to understand the causal relationship between soul and body.

How is this an answer to Elisabeth? Descartes’ point seems to be that the causal relation between soul and body seems mysterious if we rely on the intellect alone, or on the intellect together with the imagination, in order to understand it – but that it will be less so if we rely on the senses too.

The suggestion is certainly interesting, but that doesn’t mean that it is, as it stands, compelling. If Descartes meant only that, as a matter of phenomenology, the close relationship between soul and body seems perfectly obvious and natural to us, then he would certainly be correct. But of course, that isn’t really what Elisabeth is asking about. Her question is not about whether soul and body seemto us to interact, but rather about how they could in fact do so given what Descartes claims about the natures of each.

Elisabeth’s last word

Though Elisabeth and Descartes exchanged other letters in later years, in this particular exchange on the interaction problem we only know of one further letter, which is from Elisabeth – to which, as far as we can tell, Descartes did not reply. She was not convinced by his answer, for exactly the reason I mentioned. She writes: “I too find that the senses show me that the soul moves the body; but they fail to teach me (any more than the understanding and the imagination) the manner in which she does it” (emphasis added).

Her own proposed solution is to suggest that “although extension is not necessary to thought, yet not being contradictory to it, it will be able to belong to some other function of the soul less essential to her.” In other words, she proposes that soul and body can interact because the soul has, after all, extension as one of its attributes, and by means of it can cause changes in and be affected by the body in the same way that any two physical objects interact.

This is an interesting proposal that amounts to a version of what is these days called property dualism, but of a very different kind than the sort usually on offer today. Contemporary property dualists suggest that a material substance, the human body, can have both physical and non-physical attributes. What Elisabeth is suggesting is that an immaterial substance, the soul, might have both physical and non-physical attributes.

But there are two problems with this idea considered as a solution to the interaction problem facing Descartes. First, it turns out that even body-to-body interaction is not as unproblematic as Elisabeth (and most other people who comment on the interaction problem) assume. For Descartes’ abstract mathematical conception of matter is so desiccated that it is hard to see how it can have any efficacy at all with respect to anything, whether physical or non-physical. Occasionalism – attributing all causality to God rather than to anything in the created order – was a natural position for Cartesians like Malebranche to take, and Descartes himself arguably took it with regard to everything except soul-body interaction.

A second problem is that if you are going to attribute physical properties to the soul in order to explain how it interacts with the body, why not go the whole hog and make the whole body itself an attribute of the soul? That way you don’t have to posit any interaction between soul and body at all, because they will no longer be distinct substances.

Indeed, you’d be very close to returning to precisely the Scholastic conception of soul and body that Descartes was trying to replace. You’ll be treating a human being as onesubstance, not two, but a substance with both incorporeal powers (thinking and willing) and corporeal ones (seeing, hearing, digesting, walking, etc.). And I would say that that is indeed the correct solution to the interaction problem: to dissolve it by giving up the Cartesian thesis that soul and body are distinct substances, so that there aren’t any longer two things that need to “interact.”

Further comments

As I have often suggested, the real problem with Descartes’ position is not that he has trouble explaining how soul and body interact. The problem is that he thinks of them as interacting in the first place. It is that he posits twosubstances rather than one. And the reason this is a problem is that he thereby simply fails to capture the truth about human nature. For his model makes of the soul something like an angelic intellect, and the body merely one physical object in the world alongside others that an angel might push about, the way that a demon pushes about an object that it possesses (as in the case of the Gadarene swine). It makes of the body something entirely extrinsic to us (though this was certainly not his intent).

This is the force of Gilbert Ryle’s famous characterization of Descartes’ position as the theory of the “ghost in the machine.” The problem isn’t: “How does an immaterial substance have any effect on the body?” That’s no problem at all for something immaterial – after all, God and angels do it, as both Descartes and Elisabeth would have agreed. The problem is rather: “How, if soul and body are two independent substances, can the soul affect the body in the specific way that it does (rather than in the way a ghost or an angel would)?” The problem is explaining how the body could be a true partof you rather than a mere extrinsic instrument that is no more part of you than any other physical object.

Elisabeth was mistaken, then, to make a big deal of the question of soul-to-body causation as such. Of course, it is easy to think such causation mysterious if you model all causation on push-pull causation between physical objects, but as Descartes rightly says, it is a mistake to do that. (To be sure, it helps if you’re looking at the issue in the light of the complex theory of causation that the Scholastics had developed – and which Descartes himself was familiar with and had not entirely abandoned, as later modern philosophers would.)

Here’s a geometrical analogy that might be helpful. (It’s only an analogy. I am notsaying that immaterial substances are higher-dimensional objects.) Consider two-dimensional creatures of the kind described in Edwin Abbott’s Flatland. They might find talk of three-dimensional entities quite mysterious and not understand how such things could possibly “interact” with their own world. But in fact, of course, a three-dimensional entity generating effects in a two-dimensional world would be no problem at all. Similarly, while we lapse into thinking in terms of a crude push-pull model of causation and wonder: “Gee, how could an immaterial substance have any effect on matter? It’s so mysterious!”, the angels and demons look on thinking: “Seriously? How pathetic.” As the Scholastics would say, immaterial substances exist and operate at a higherontological level than we do, not a lower one. And higher orders have no difficulty affecting lower ones. We might find it mysterious how they do so, but that is unremarkable considering that our cognitive faculties are primarily geared toward understanding the lower, material order.

What would be truly problematic is a lower order affecting a higher one. For example, a two-dimensional entity would have great difficulty having any effect on a three-dimensional one, at least if the three-dimensional one doesn’t cooperate. And in an analogous way, it is mysterious how a purely material substance could have any effect on an immaterial substance.

This is why Elisabeth’s point about body-to-soul causation is so important. If soul and body are two distinct substances, then even if the soul could, as a substance of a higher ontological order, produce effects in the body (even if only in the way an angel might), it is nevertheless entirely mysterious how the body could produce effects in the soul (any more than a stone or a tree could have any effect on an angel or demon).

This problem does not arise for the Scholastic conception of soul and body, because, again, it does not regard them as distinct substances in the first place. A human being is one thing, not two, albeit a thing with both corporeal and incorporeal activities. And since it is one thing, the question of interaction does not arise.

Related posts:

Mind-body interaction: What’s the problem?

January 25, 2021

Koons on time and relative actuality

Rob Koons has reactivated his Analytic Thomist blog, which you must check out if you are interested in metaphysics done in a way that brings analytic philosophy and Thomism into conversation. Rob was also recently interviewed on the What We Can’t Not Talk About podcast on the topic of Aristotle and modern science. That topic is the focus of his recent work, and he has been especially interested in how Aristotelians ought to approach quantum mechanics and the nature of time.

Rob Koons has reactivated his Analytic Thomist blog, which you must check out if you are interested in metaphysics done in a way that brings analytic philosophy and Thomism into conversation. Rob was also recently interviewed on the What We Can’t Not Talk About podcast on the topic of Aristotle and modern science. That topic is the focus of his recent work, and he has been especially interested in how Aristotelians ought to approach quantum mechanics and the nature of time. The latter subject is the focus of some of his latest blog posts, and also something about which Rob and I recently had an exchange in the pages of the American Catholic Philosophical Quarterly. In Aristotle’s Revenge, I argue that while Aristotelianism can in principle be reconciled with either the A- or the B-theory of time, the A-theory is by far the more natural view to take, and the presentist version of the A-theory especially. Rob disagrees, and argues that Aristotelian metaphysics is equally compatible with either theory or with some third, intermediate theory. We hash this out in some depth in the ACPQexchange, and Rob repeats some of his main theses in the recent blog posts. Here I’ll reiterate some of my own misgivings about his position.

The B-theory of time holds that past, present, and future things and events are all equally real, and that temporal passage and the nowor present are illusory. The A-theory, by contrast, takes temporal passage and the now or present to be real. The presentist version of the A-theory also holds that, where time is concerned, only present things and events are real. (A presentist could allow that there are also things that exist altogether outside of time, either eternally or aeviternally.) The “growing block” version of the A-theory holds that present and past events are real. The “moving spotlight” version of the A-theory allows that past and future events are as real as present ones.

One of the issues that arises in the ACPQexchange is whether the B-theory can accommodate notions of change and efficient causation robust enough for an Aristotelian. I argue that it cannot. Change and efficient causation, on an Aristotelian account, entail the actualization of potentiality. But it seems that on a B-theory, since all past, present, and future things and events are equally real, everything is actual, and there is no real potentiality. Hence there is no real efficient causation or change. The theory collapses into an essentially Parmenidean position, at least with respect to time and change.

Rob’s response to this is to suggest that a B-theorist could affirm both actuality and potentiality by speaking of relativeactualities and potentialities. Consider a banana that is green at time t1, yellow at time t2, and brown at time t3. True, the B-theory holds that from an absolutepoint of view, times t1, t2, and t3 are equally real, and that the greenness, yellowness, and brownness of the banana are all equally actual. Nevertheless, relative to t1, only the greenness is actual and the yellowness and brownness are merely potential; relative to t2, the greenness is no longer actual but the yellowness is actual, and the brownness remains potential; and so on. Rob develops this proposal in his ACPQ article and briefly summarizes it in his recent blog posts.

But I don’t think this works. Here’s one problem with it. Suppose someone suggested that time was nothing more than a spatial dimension. I reject this view, and Rob wants to avoid it too. One problem with it is that it also seems incompatible with the existence of real potentialities in the world. If past, present, and future events are equally real in exactly the same way that the spatially separated hot and cold ends of a fireplace poker are (to borrow a famous example from McTaggart), then it seems that they are equally actual, just as the hot and cold ends of the poker are equally actual. There is no real potentiality in a spatialized conception of time, and thus no real change – and thus, really, no timeeither.

But suppose our imagined spatializer of time defended his view by saying that there is potentiality of at least a relative sort on his conception of time. Suppose he appealed to the poker analogy, and suggested that we could say that relative to the left side of the poker, the poker was actually cold but potentially hot, whereas relative to the right side, it was actually hot and potentially cold. Suppose he suggested that there was therefore a kind of “change” in the poker from left to right. And suppose he suggested that a similar kind of relative actuality and potentiality could be attributed to things and events at his spatialized points of time, and that a similar kind of change could therefore be attributed to them too.

In my view this would be clearly fallacious, involving little more than a pun on the word “change.” (See Aristotle’s Revenge for detailed criticism of spatialized conceptions of time.) I imagine Rob might agree, since, as I say, he too wants to avoid spatializing time, or at least denies that the B-theory need be interpreted as spatializing it. But I fail to see how Rob’s notion of relative actuality and potentiality captures real potentiality, and thus real change, any more than my imagined spatializer of time does.

Here’s another way of thinking about the problem. How does talk about relative actuality and potentiality capture real change or efficient causation any more than if we were to describe the objects and events of a fictional story as “relatively actual” (that is, relative to the story) even if they are from an absolute point of view merely potential (since the story is fictional)? We need to know what it is, specifically, about Rob’s conception of the relation between the banana’s being green at t1and yellow at t2 that makes the transition from the one to the other any more a case of real change involving real causation than the events of a fictional story are.

In short, talk of “relative actuality” and “relative potentiality” by itself doesn’t seem sufficient to do the job Rob needs it to do. For we could use such language to describe an entirely spatialized conception of time, and yet it wouldn’t really give us genuine potentiality. Or we could use it to describe an entirely fictional world, and yet it wouldn’t give us genuine actuality. The notion of being “relatively” actual or potential seems – by itself, with no further elaboration – too thin to do the needed metaphysical work. (I criticize Rob’s position in more detail in the ACPQpaper.)

Related posts:

Cundy on relativity and the A-theory of time

Gödel and the unreality of time

Vallicella on the truthmaker objection against presentism

Vallicella on existence-entailing relations and presentism

Aristotelians ought to be presentists

More on presentism and truthmakers

Craig contra the truthmaker objection to presentism

January 21, 2021

Narrative thinking and conspiracy theories

“Just because you're paranoid doesn't mean they aren't after you” is one of the most famous lines from Joseph Heller’s Catch-22. I propose a corollary: Just because they’re after you doesn’t mean you’re not paranoid.

In a pair of articles at Rorate Caeli (hereand here), traditionalist Catholic historian Roberto de Mattei offers some illuminating observations about paranoid modes of thinking trending in some right-wing circles, such as the QAnon theory. These are usually criticized as “conspiracy theories,” but as De Mattei points out, that they posit malevolent left-wing conspiracies is not the problem. Left-wing ideas really do dominate the news media, the universities, the entertainment industry, corporate HR departments, and so on. Left-wing politicians and opinion makers really are extremely hostile to traditional moral and religious views, and in some cases threaten people’s freedom to express them. A transformative project like The Great Reset is not the product of right-wing fantasy – it has its own official website, for goodness’ sake. Left-wingers in government, the press, NGOs, etc. have common values and goals and work together to advance them. The “conspiring” here is not secret or hypothetical, but out in the open.

Disordered minds

The problem is rather that the specific kinds of conspiracy theory De Mattei has in mind are epistemologically highly dubious. Now, one way a conspiracy theory might be epistemologically problematic has to do with the structure of the theory itself. For example, I have argued that a problem with the most extreme sorts of conspiracy theory is that they are like the most extreme sorts of philosophical skepticism, in being self-undermining. De Mattei’s focus, by contrast, is on the psychological mechanism by which such theories come to be adopted. He writes:

The characteristic of false conspiracy theories is that they cannot offer any documentation or certainty. To compensate for their lack of proofs, they use the technique of narration, which takes hold of the emotions, more than reason, and seduces those, who by an act of faith, have already decided to believe the far-fetched, propelled by fear, anger and rancor.

De Mattei elaborates on the cognitive mechanism involved in his other article, as follows:

Bad use of reason leads to the precedence of the imagination, a form of knowledge which does not follow logical steps, but [is] often determined by an emotional state. Reason is substituted by fantasy and demonstration is substituted by narration. To explain the significance of the term phantasia, Aristotle indicates its derivation from light (pháos). Just as luminous stimulus generate visual sensations, thus the mind produces internally “phantasms” (phantásmata) or images that don’t always correspond to reality. Every image that makes an impression on our mind therefore, must be verified by the light of reason, which is the highest faculty of the soul…

These ideas circulating in the blog-sphere appear seductive to many, but are expressed in the form of “narration”, more than argumentation. What renders them fallacious is not the conspiratorial theory underlying them, but the presumption of establishing a theory through arguments of a merely circumstantial nature… Those who sustain these theses then, often use “flash sophism”, which consists in having recourse to generic phrases and peremptory sentences, which do not convince the sage, but make an impression on the uneducated.

End quote. Let’s unpack what De Mattei is saying here. First, he appeals to the standard Aristotelian-Thomistic distinction between the imagination, the passions, and the intellect. The imagination is that faculty by which we form and entertain mental images or “phantasms,” which can be thought of as faint copies of what has been, or could be, experienced through the senses. Examples would be the images you call to mind of what your mother’s face looks like or what her voice sounds like, or of the smell or taste of the Christmas dinner you shared when you last saw her. The passions are affective states that incline us toward or away from various actions or objects – a flash of anger that inclines us to lash out at someone, a twinge of nostalgia that leads us to open up the photo album, the feeling of joy that follows the hearing of a favorite piece of music, and so on.

The imagination and the passions have their own principles of operation, and they are the kind typically emphasized by (and overgeneralized by) empiricist and associationist theories in psychology. For example, the appearance in consciousness of one image will naturally tend to trigger the appearance of other images which it has in the past been associated with. You hear mom’s voice on the answering machine, and the next thing you know, you “see” the image of her face with your mind’s eye. That in turn triggers warm feelings of affection and nostalgia. Those may in turn generate memories of childhood events, which in turn trigger other emotions. And so on. None of this is irrational or per se contrary to reason, but it is not rationaleither – that is to say, the progression from one image or passion to another is not a matter of logical inference or even, necessarily, of conceptual connections, but rather of contingent habituation.

The intellect, by contrast, is concerned precisely with abstract concepts, complete thoughts or propositions, and their logical interrelationships. To be sure, in human beings the intellect operates in tandem with the imagination and the passions. But the content of a concept, of a proposition, or of the string of propositions that make up an argument, outstrip anything that can even in principle be captured in imagery or in any affective state. What the intellect does differs in kind, and not merely in degree, from anything the imagination and the passions do.

Again, this is just standard Aristotelian-Thomistic psychology. And it is absolutely essential to understanding human nature and the moral life. We share the imagination and passions with non-human animals. But the intellect is what sets us apart from them, the angelic side of the mashup of angel and ape that is the human being. And it transforms and ennobles our imaginations and passions, imposing an overlay of conceptual and logical order on what would otherwise be an instinctive and habitual, but strictly unintelligent, play of images and passions.

Now, when a human mind is properly ordered, the imagination and passions conform themselves to the intellect. But when the intellect is instead pushed around by an excessively powerful imagination and/or passions, all sorts of irrationality and immorality can result. A person given to excessive anger will see offenses and bad motives where there are none, or see great offenses where there are really only small ones. A person given to excessive worry will foresee difficulties where there are none, or insurmountable difficulties where there are in fact perfectly manageable ones. And so on.

These are examples of how imagination and passion can distort rational judgment in the individual. But disordered habits of imagination and feeling can become so widespread that they come to characterize a whole society. An example would be the extreme sexual depravity that surrounds us today – indeed, in which contemporary human minds are veritably marinating, with the effect of rotting out their capacity for sober rational judgment (as Aquinas warns that sexual vice has, of all vices, the greatest propensity to do). A major contributor to this is the near omnipresence of online pornography, which habituates the user to highly disordered and unrealistic imaginative scenarios and passions. The depth of the disorder is evidenced by the fact that the very idea that there are two sexes and that the sexual act is of its nature oriented to procreative and unitive ends – blindingly obvious for all of previous human history to even the least educated of rational minds – has now come to be regarded by millions of people as a hateful lie, a mark of bigotry that must be shouted down or even censored. This is mass psychosis. (To quote Catch-22 again: “Insanity is contagious.”)

Narrative thinking

What does all this have to do with the kinds of epistemologically untethered conspiracy theories that De Mattei is criticizing? In a key insight, De Mattei says that such theories are rooted in a kind of “narration” rather than “argumentation.” What does he mean by this?

Think of the differences between a story and a line of philosophical argument. The parts of a story are not connected together in the way that the steps of an argument are. In an argument, one proposition is logically entailed by, or made probable by, another. That is not the way one event is related to another in a story. Of course, we might speak in a loose way of there being a logical progression of events in a good story, but what we mean by that is that the progression is well-plotted, or true to the characters’ motivations, or what have you. Ultimately, we judge the story by criteria of aesthetics and personal taste that differ from the dry and dispassionate logical criteria by which we evaluate an argument. And those criteria of aesthetics and personal taste have much to do with the affective reaction a story produces in us, and the pleasant or striking imagery it generates.

De Mattei’s point is that conspiracy theories of the kind he has in mind stand in need of dry and dispassionate logical evaluation, but in fact tend to be embraced for reasons similar to the kind that are operating when we are attracted to a good story or narrative. And this occurs because those drawn to such theories are excessively given to passion and imagination and allow these to dominate their intellects.

Of course, since even a person with overdeveloped passions and imagination is still a rational animal, his intellect is also engaged in evaluating the theory. But the problem is that, pushed around by his imagination and passions, his intellect is too easily satisfied with arguments that are actually far from logically compelling – with what De Mattei calls merely “circumstantial” evidence and with “generic phrases and peremptory sentences,” e.g. clichés about the motives of those in power, and the confident pronouncements of purported experts. Everything seems to “fit,” but only because the narrative is highly attractive given one’s passions and general background beliefs, not because the evidence and arguments are actually as powerful as is assumed. By means of the mechanisms whereby phantasms are generated and come to be associated, images of one sort (of real injustices occurring, of real and widespread expressions of hostility to one’s values, etc.) tend to prompt further images (e.g. of shadowy conspirators in smoke-filled rooms). The psychological ease with which one image tends to generate another in consciousness is mistaken for a logicalconnection between premises and conclusion.

A person who has fallen in love with such a narrative may even start to feel part of it himself, like a character in an action film who is going to assist in bringing the story to a climax. Before you know it, he’s drunk the QAnon Kool-Aid and is ready to throw the Georgia Senate elections in order to stick it to the RINOs, or to invade the Capitol building.

Conspiracy theorizing of this kind involves something like the Slippery Slope fallacy in reverse. In a Slippery Slope fallacy, one judges too hastily that some action or policy A will lead to some bad outcome Z, but without explaining how to fill in the causal gaps by which A would plausibly lead to Z. In paranoid thinking of the kind evident in extreme conspiracy theories, one starts with some genuinely bad phenomenon Z (say, bureaucratic resistance to policies that would help the working class and end pointless wars) and posits a bizarre cause A (for example, a conspiracy of cannibalistic Satan-worshipping pedophiles), without explaining why the series of causes leads back to A, specifically, as opposed to some less exotic principal cause. What the conspiracy theorist doesn’t realize is that even though the phenomenon Z is real and is bad, it doesn’t follow that he’s not reacting to it in a paranoid way.

The tendency De Mattei is describing is not a deterministic one. The point isn’t that passion and imagination become so powerful that the intellect is left utterly helpless. A sufficiently powerful intellect or will can resist the errors into which even deep-seated disordered fleshly desires might otherwise lead one, as the examples of Plato and St. Augustine show. Similarly, a person given to paranoid delusions can come to know that he is, and try to correct for it (a famous extreme case being that of John Nash). But given the pull of the passions and the imagination, a paranoid narrative can become addictive. And as the AA folks tell us, the first step is to admit the problem.

Gnostic narratives

Narrative thinking not only reinforces crackpot conspiracy theories, but can also facilitate disorders of the passions and the imagination of the other kinds mentioned above. Indeed, narrative thinking is a major factor behind the now widespread acceptance and celebration of sexual desires and practices that have traditionally been considered aberrant. One concocts a story like the following: “These aren’t just weird desires and feelings. They reflect who I am, my identity. Those who criticize them are therefore trying to hurt me. Indeed, they are part of a long history of oppression of people like me. Our story is one of victimization, and the climax of the story must be liberation.” Repeat this little narrative to yourself over and over and you’ll almost believe it. Yell it in other people’s faces with enough worked-up outrage, and it starts to feel natural. Get other people to repeat it back to you and to share in the yelling, and you’re not only fully convinced, but have the makings of a pseudo-moralistic crusade. It helps if you’re part of a generation raised on social media, video games, cosplay, Critical Theory, and other insulations from objective reality. The narrative provides meaning in a world from which traditional meanings have disappeared, and license to violate norms that have collapsed with the disappearance of those traditional meanings.

This is true of “woke” thinking more generally. In an earlier post I discussed how Critical Race Theory and QAnon alike are contemporary manifestations of the same paranoid mindset that underlies the ancient Gnostic heresy. Now, Gnosticism is nothing if not a narrative-oriented rather than rational mode of discourse. And Critical Race Theory is explicitly and self-consciously so. Richard Delgado and Jean Stefancic’s widely read primer on the subject devotes a chapter to surveying the ways that CRT writers deploy “narrative” and “storytelling” as rhetorical weapons – in particular, the spinning of “counterstories” and “alternative realities” as devices for undermining people’s confidence in the “narratives” CRT claims to be oppressive. All in the context of badmouthing rationalism, objectivity, etc. as masks for “white supremacy.” This is nothing less than the making of textbook logical fallacies (appeal to emotion, hasty generalization, the genetic fallacy, poisoning the well, begging the question, etc.) the methodological foundation of an entire academic industry. The whole thing is no less a sick fantasy world than the QAnon lunacy is. The difference is that QAnon doesn’t get shoved down your throat by the HR department, 10 million dollar corporate grants, New York Times bestseller status, etc.

All the same, QAnon is not harmless crankery, as the appalling events at the Capitol show. And it is, in any event, a waste of time and energy to try to ferret out hidden left-wing malevolence when what we ought really to worry about is the kind that is already being frankly expressed. From Catch-22 again:

“Subconsciously there are many people you hate.”

“Consciously, sir, consciously,” Yossarian corrected in an effort to help. “I hate them consciously.”

But let’s give the last word to De Mattei:

The existence of a conspiracy aiming at the destruction of the Church and Christian Civilization is in no need of new theories, since it has already been proven by history; neither does it need secrecy, since the Revolution now acts boldly, openly.

Related posts:

The Gnostic heresy’s political successors

The Bizarro world of left-wing politics

January 15, 2021

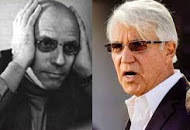

McGinn on the question of being

Colin McGinn is a philosopher whose work I always find interesting even when I disagree with it, which is often. His book

Philosophical Provocations: 55 Short Essays

is made to be dipped into when one is in the mood for something substantive but not too heavy going. And it is accurately titled, since on reading it I was indeed provoked – specifically, by the article on “The Question of Being.”

Colin McGinn is a philosopher whose work I always find interesting even when I disagree with it, which is often. His book

Philosophical Provocations: 55 Short Essays

is made to be dipped into when one is in the mood for something substantive but not too heavy going. And it is accurately titled, since on reading it I was indeed provoked – specifically, by the article on “The Question of Being.” McGinn characterizes the issue as:

the question [of] …what it is for something to have being. What does existence itself consist in – what is its nature? When something exists, what exactly is true of it? What kind of condition is existence? How does an existent thing differ from a nonexistent thing? (p. 211)

He makes several important observations about this question. First, it is a serious philosophical question, but one that is distinct from the issues that analytic philosophers tend to confine themselves to when discussing existence. In particular, it is distinct from questions about whether “exists” is a first- or second-level predicate, and it is distinct from questions about what sorts of things we should allow into our ontology (material objects, numbers, moral values, universals, etc.). Analytic philosophers have a lot to say about those questions, but little to say about the question of being.

Second, McGinn says that the question is not plausibly addressed by philosophical views which are essentially anthropocentric (such as verificationism, pragmatism, and some versions of idealism). Since human beings could have failed to exist, it cannot be correct to think of existence in terms of what we could empirically verify, or what is useful to us, or what we perceive.

Third, McGinn correctly notes that empirical science cannot answer the question either. There can be a science of particular sorts of existing things – plants, animals, chemical elements, basic particles, and so on. But “there cannot be an empirical science of existence-as-such” (p. 213). He does not elaborate, but since part of what is involved in the question of being is whether what exists outstrips what is material or empirically detectable, it obviously cannot be answered by way of methods that confine themselves to matter and the empirical.

So far so good. McGinn also correctly notes that even if we take the view that the notion of existence is primitive and unanalyzable, “it should be possible to say somethingilluminating about it – not provide a classical noncircular analysis, perhaps, but at least offer some elucidatory remarks” (p 211).

Analytic myopia?

So why was I provoked? Because McGinn also claims that in the history of philosophy, the question of being “has been ignored, evaded perhaps” (p. 212). Indeed:

There is a huge gap at the heart of philosophy: the nature of existence. In fact, we might see the history of (Western) philosophy as a systematic avoidance of this problem. We have not confronted the question of being, not head on anyway. (p. 211)

and:

When philosophers started to organize and educate, a few thousand years ago, they would be tacitly aware of the problem but had nothing useful to communicate, so they left it alone, kept it off the syllabus, and discouraged students from raising it. And today we still have no idea what to say, beyond the two questions I mentioned earlier. (p. 213)

Seriously?! Has McGinn not heard of Parmenides? Plato on being and becoming? Avicenna? Aquinas’s De Ente et Essentia? Heidegger’s Being and Time? Sartre’s Being and Nothingness? Gilson’s Being and Some Philosophers? Obviously he must have. And that’s just scratching the surface. Nor has the question in fact been ignored by all analytic philosophers, as evidenced by books like Barry Miller's The Fullness of Being and Bill Vallicella’s A Paradigm Theory of Existence. So, what the hell is McGinn talking about?

Of course, Heidegger famously alleged that Western philosophy after Plato had evaded the question of being. But McGinn can’t mean what Heidegger meant, since he cites neither the Pre-Socratics nor Heidegger himself as exceptions to the charge that philosophers have “ignored” or “evaded” the question of being.

My guess is that McGinn simply has the myopia stereotypical of analytic philosophers (even if not actually fairly attributable to all of them). To be sure, McGinn’s work often does engage seriously with the history of philosophy, though his range of knowledge of and interest in it seems not to extend before the early modern period. And it would be churlish to criticize him too harshly, since, as I say, he doestake the question seriously (which a truly myopic analytic philosopher would not do).

Still, the fact remains that it is hard to see how anyone even vaguely familiar with ancient and medieval philosophy could make the assertions he does. And even analytic philosophers should know better – and as I have said, often do know better. For example, thinkers like Wilfrid Sellars and Richard Rorty seriously engaged with the pre-modern history of philosophy. Indeed, though they couldn’t be farther from Thomism, they knew of and to some extent engaged with the Thomist tradition as it existed in their day (mainly as filtered through writers like Gilson, Maritain, and Mortimer Adler).

One of the big themes of the Thomism of those days was the way that Thomism offered a deeper analysis of the nature of existence than the existentialism that was then all the rage. For example, Maritain’s Existence and the Existent is devoted to that theme. Now, as a Thomist whose training was originally in analytic philosophy, even I find Maritain’s style sometimes a bit hard to take. So, you can be sure that McGinn would find it even more so. All the same, such books evidence just how deeply the question of being was in fact being addressed by thinkers whose work earlier analytic thinkers engaged with. And even some prominent contemporary analytic philosophers whose work McGinn would know are still engaging with them – consider, for example, Anthony Kenny’s book Aquinas on Being.

So, we’re not talking even six degrees of separation here. Even given analytic myopia, it is remarkable that McGinn would make statements so bold, sweeping – and embarrassingly easy to prove false – as he did. A few minutes of Googling should have dissuaded him.

The Thomist account

You don’t have to read far into a book like Maritain’s to see that he offers exactly what McGinn asks for – an account (drawn, of course, from Aquinas) that tries to be “illuminating” and “elucidatory” even if it takes being to be in a sense primitive. We have the classic Thomistic themes:

- Being is a broader notion than existence. After all, the essence of a thing has a kind of being or reality, but it is (as the classic Thomistic doctrine holds) really distinct from the existence of a thing.

- Potentiality is a kind of being that is really distinct from actuality, and intermediate between actuality on the one hand and nothingness on the other. Recognizing this distinction is essential to avoiding Parmenidean static monism on the one hand (which posits a world of pure being with no becoming), and Heraclitean dynamism on the other (which posits a world of pure becoming with no being).

- Connecting these two distinctions, the essence of a thing, considered in isolation, is a kind of potential being, and the existence of a thing is what actualizes that potential.

- Being is an analogical notion, where analogy is a literal middle ground usage between the univocal and the equivocal use of terms. A substance, its attributes, its form, its matter, its essence, its existence, etc. all have being, but not all in exactly the same sense (even if not in equivocal senses either).

- Being is not a genus nor a universal of any kind. The relationship between individual beings and Being Itself is not the relation between instances of a kind and the abstract kind of which they are instances. It is rather a causal relation between that which requires that existence be added to its essence in order for it to be part of the world, and that which does not.

And so on. You might reject all this. You might judge that, at the end of the day, it doesn’t hold up, perhaps for reasons like Kenny’s. (Though you shouldn’t – see my Scholastic Metaphysics for exposition and defense of the Thomist position.) But you can’t deny that it amounts to exactly the sort of thing McGinn says we need and claims that philosophers have studiously avoided – a worked-out attempt to elucidate the nature of being. And of course, Thomism is not the only school of thought that has tried to offer that, as the history of ancient and medieval philosophy (and even much modern philosophy) shows.

Contra antirealism

McGinn himself has some illuminating remarks to make in another article in the volume titled “Antirealism Refuted.” To be sure, they’re not presented as an attempt to elucidate the question of being. All the same, one of the ways that both common sense and philosophy try to understand reality is by contrast with thought. For example, if you ask the average person what it means to say that unicorns are not real, he is likely to say that they are merely imaginary – that they cannot be found outside the mind.

Now, antirealist views in philosophy treat various phenomena that common sense takes to be real as if they had no existence outside thought, or outside language, or outside cultural practice, or what have you. For example, an antirealist about moral value might say that morality has no foundation in objective reality, but reflects only our emotional states or cultural practices. An antirealist about physical objects might say that physical substances are mere fictions that allow us to organize our experiences, or that the very notion of a substance (physical or otherwise) is a shadow of the subject-predicate structure of language but corresponds to nothing in reality.

McGinn points out that an antirealist view about some subject matter is essentially an error theory. It holds that we systematically just get things wrong about that subject matter. But interestingly, none of the usual sources of error can plausibly explain why we would be subject to the errors antirealism attributes to us. Nor do antirealist theories offer plausible alternative suggestions about the source of the purported error.

McGinn points out, for example, that errors in astronomy might arise from perceptual illusion, errors in morality from prejudices, errors in politics from indoctrination, and so on. But none of these sources plausibly explain the sorts of errors posited by metaphysical antirealism. For example, even when none of the usual sources of perceptual illusion are operating, the antirealist about physical objects says we are still erring in judging them to be real. But how? What exactly is the source of this error if it is not (say) bad lighting, refraction, malfunctioning eyeballs, etc.? We might claim, with more or less plausibility, that some specificmoral opinion arises from prejudice. But how exactly would the more general belief that there is such a thing as objective morality in the first place arise from prejudice?

McGinn’s basic argument against antirealism, then, is that it is an error theory that has no workable theory of error. How might this elucidate the nature of being or reality? Again, McGinn himself does not apply his argument to that particular question. But it is relevant. For error presupposes the distinction between truth and falsity. And antirealism itself implicitly supposes that error – the failure to attain truth – entails a lack of correspondence between thought and reality, whereas there would be such a correspondence if we were not in error.

So, the realism/antirealism debate itself presupposes a conception of being or reality as something extra-mental, to which the mind conforms when it attains truth. Being is a correlate of truth. That gives us at least the beginnings of the kind of “illuminating” or “elucidatory” account of being that McGinn wants. And here too the Thomistic tradition – which, in its endorsement of the medieval notion of the “transcendentals,”also says of being that it is convertible with truth (and with goodness, unity, etc.) – provides ingredients for developing the analysis further.

Related reading:

January 8, 2021

The Gnostic heresy’s political successors

The Western world is the creation of the Church, and the crisis of the West is always at bottom the crisis of the Church. This is especially so where the Church has receded into the background of the Western mind – where men’s plans are hatched in the name of progress, science, social justice, equity, or some other purportedly secular value, and make little or no reference to religion. For liberalism, socialism, communism, scientism, progressivism, identity politics, globalism, and all the rest – this Hydra’s head of modernist projects, however ostensibly secular, is united by two features that are irreducibly theological.

The Western world is the creation of the Church, and the crisis of the West is always at bottom the crisis of the Church. This is especially so where the Church has receded into the background of the Western mind – where men’s plans are hatched in the name of progress, science, social justice, equity, or some other purportedly secular value, and make little or no reference to religion. For liberalism, socialism, communism, scientism, progressivism, identity politics, globalism, and all the rest – this Hydra’s head of modernist projects, however ostensibly secular, is united by two features that are irreducibly theological. First, they are all essentially apostateprojects, enterprises that have arisen in the midst of Christian civilization with the aim of supplanting it. And they could have arisen only within the Christian context, because, second, these projects are all heretical in the broad sense of that term. That is to say, they are all founded on some idea inherited from Christianity (the dignity of the individual, human equality, a law-governed universe, a final consummation, etc.) but removed from the theological framework that originally gave it meaning, and radically distorted in the process.

As an essentially apostate and heretical phenomenon, modernity is also an Oedipal phenomenon. Its series of grand, mad schemes amount to the West fitfully seeking – now this way, now that – finally to free itself from the authority of its heavenly Father and to defile the doctrine of its ecclesiastical Mother. And in the process, the would-be parricides always make themselves over into parodies – remolding the world in their image, suppressing dissent, and otherwise acting precisely like the oppressive God and Church that haunt their imaginations.