Edward Feser's Blog, page 36

July 24, 2020

No urgency without hell

A common argument in defense of the eternity of hell is that without it, there would be no urgency to repent or to convince others to repent. Call this the “argument from urgency.” One objection to the argument is that it makes true virtue impossible, since it transforms morality into a matter of outward obedience out of fear, rather than inward transformation out of sincere love of God. Another is that it adds a cynical scare tactic to the moral teaching of Christ, the beauty of which is sufficient to lead us to repentance when it is properly presented.

A common argument in defense of the eternity of hell is that without it, there would be no urgency to repent or to convince others to repent. Call this the “argument from urgency.” One objection to the argument is that it makes true virtue impossible, since it transforms morality into a matter of outward obedience out of fear, rather than inward transformation out of sincere love of God. Another is that it adds a cynical scare tactic to the moral teaching of Christ, the beauty of which is sufficient to lead us to repentance when it is properly presented. Scare tactics?

But these objections rest on misunderstandings, or at least fail to take the argument on in its strongest form. To see what is wrong with the first objection, consider an analogy. Suppose someone is driving a car at 100 mph toward a cliff. Whether from the passenger seat or (hopefully, for your sake) by cell phone, you urge him to slow down and change course, warning that he is headed for certain death. Suppose a third party interjects: “Oh come on, resorting to scare tactics is a cynical, manipulative way to get someone to change his ways! Sure, you might terrorize him into slowing down, but only out of fear rather than a sincere appreciation for safe driving practices. Why not instead exhort him in a way that is likelier to transform his inward attitudes? For example, why not laud the beauty and reasonableness of safe driving? And why not reassure him that in any event we may have good hope that he won’t go off the cliff?”

Is this wise and morally refined advice? Of course not. It is foolish and sentimental advice, sure to result in the driver’s death. There are two problems with it. First, it treats the driver’s bad behavior and the prospect of his going off the cliff as if they were only contingently related – as if the bad behavior had no inherent tendency to lead one off the cliff, so that you may or may not bring it up when trying to reform the behavior. In reality, of course, going off of the cliff is the inevitable result of the bad behavior, and to leave it out is not only to fail to tell the whole story about the nature of the bad behavior, but to leave out the most important part of the story.

Now, in the same way, being in thrall to sins of greed, lust, envy, wrath, pride, and so on of its very nature tends to harden one’s soul into an orientation away from God and toward something less than God. And that means that the more hardened one is in such an orientation, the more likely that that is what one’s soul will be “locked” onto at death. One will, as it were, then go “off the cliff” toward which one had been speeding prior to death. But to be forever locked onto an end other than God is just what it is to be damned. So, to warn sinners of hell is not some unnecessary exercise in scare tactics, any more than warning the driver of his certain doom is. Rather, as with the warning to the driver, it is simply to give a complete description of where someone’s behavior will of its nature inevitably lead him if he does not change course.

That is the traditional Christian understanding of the effects of sin, and the Thomist tradition gives one possible way of understanding the underlying metaphysics. Whether or not you agree with that understanding or the proposed underlying metaphysics, the point is that it is a mistake to interpret the threat of hell as a mere scare tactic that has nothing to do with motivating inward moral transformation. On the contrary, it is precisely a warning of what a failure to achieve a genuine inward moral transformation will inevitably lead to.

But that is by no means to concede that scare tactics are always out of place. That is the second point illustrated by the driving example. If a guy is speeding toward a cliff, what charity demands is not reassuring him that everything will be OK, but precisely scaring the hell out of him so that he’ll change course. Similarly, sometimes warning someone of the prospect of hell can be the best way, maybe even the only way, to get him to reconsider the sort of evil life he is living.

Yes, fear of punishment is not the whole of the story of the moral life, or even the most important part of the story. No Catholic defender of the doctrine of hell denies that; on the contrary, such defenders emphasize that perfect contrition, sorrow out of love of God, is the only way a person can be saved outside of sacramental confession. But it simply does not follow that fear of punishment is never even part of the story. It can be precisely the first step in the process of inward moral transformation, even if it is far from the last step. Everyone knows that this is true in everyday life – that the prospect of prison, or financial ruin, or death, or loss of reputation or friends or family, can lead a criminal, a drug addict, an adulterer, or a greedy person, to reconsider the path he is on. There is no reason at all why fear of hell might not do the same.

Christ’s urgency

It would also be quite silly to pretend that the argument from urgency is something defenders of the doctrine of hell have added to Christ’s teaching. No, the argument is rather that the reality of eternal damnation is the only way to make sense of the urgency that is already there in Christ’s own teaching. Consider some passages just from Matthew’s Gospel:

For I tell you, unless your righteousness exceeds that of the scribes and Pharisees, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven. (Matthew 5:20, RSV)

If your right eye causes you to sin, pluck it out and throw it away; it is better that you lose one of your members than that your whole body be thrown into hell. And if your right hand causes you to sin, cut it off and throw it away; it is better that you lose one of your members than that your whole body go into hell. (Matthew 5:29-30)

Enter by the narrow gate; for the gate is wide and the way is easy, that leads to destruction, and those who enter by it are many. For the gate is narrow and the way is hard, that leads to life, and those who find it are few. (Matthew 7:13-14)

And do not fear those who kill the body but cannot kill the soul; rather fear him who can destroy both soul and body in hell. (Matthew 10:28)

But I tell you that it shall be more tolerable on the day of judgment for the land of Sodom than for you. (Matthew 11:24)

Therefore I tell you, every sin and blasphemy will be forgiven men, but the blasphemy against the Spirit will not be forgiven. And whoever says a word against the Son of man will be forgiven; but whoever speaks against the Holy Spirit will not be forgiven, either in this age or in the age to come. (Matthew 12:31-32)

I tell you, on the day of judgment men will render account for every careless word they utter; for by your words you will be justified, and by your words you will be condemned. (Matthew 12:36)

Just as the weeds are gathered and burned with fire, so will it be at the close of the age. The Son of man will send his angels, and they will gather out of his kingdom all causes of sin and all evildoers, and throw them into the furnace of fire; there men will weep and gnash their teeth. (Matthew 13:40-42)

Again, the kingdom of heaven is like a net which was thrown into the sea and gathered fish of every kind; when it was full, men drew it ashore and sat down and sorted the good into vessels but threw away the bad. So it will be at the close of the age. The angels will come out and separate the evil from the righteous, and throw them into the furnace of fire; there men will weep and gnash their teeth. (Matthew 13: 47-50)

You serpents, you brood of vipers, how are you to escape being sentenced to hell? (Matthew 23:33)

Afterward the other maidens came also, saying, ‘Lord, lord, open to us.’ But he replied, ‘Truly, I say to you, I do not know you.’ (Matthew 25:11-12)

For to every one who has will more be given, and he will have abundance; but from him who has not, even what he has will be taken away. And cast the worthless servant into the outer darkness; there men will weep and gnash their teeth. (Matthew 25:29-30)

Then he will answer them, ‘Truly, I say to you, as you did it not to one of the least of these, you did it not to me.’ And they will go away into eternal punishment, but the righteous into eternal life.” (Matthew 25:45-46)

Now, I submit that anyone reading these for the first time and with no knowledge of the dispute over universalism would naturally take Christ to be saying that there will be a day of judgment where the wicked will be condemned forever, that there are sins that will never be forgiven, that this sorry fate cannot be escaped, that few will avoid it, that it is so dire that it is better to lose an eye, a hand, or even one’s whole body than to fall into it, and that there is a finality to this judgement that entails an urgency to repent now in order to avoid it.

Of course, annihilationists would say that the damned don’t sufferforever but are simply destroyedforever. I have argued against this view elsewhere, but what matters for the moment is that even the annihilationist agrees that Christ’s words entail an irrevocable condemnation of the wicked for their failure to repent of the sins of this life. What you cannot get out of passages like these is the universalist view that all will in fact be saved, that every sin will be forgiven, that no one will be condemned forever, etc.

Universalist non-urgency

There is a kind of Orwellian perversity to the universalist’s way of dealing with texts like these. Out of one side of his mouth, he admits – he has to, because it is undeniable – that such passages seem incompatible with universalism. It’s just that he modesty proposes that there are other ways of reading them that can be reconciled with his position. Even David Bentley Hart, in That All Shall Be Saved, acknowledges the “highly pictorial and dramatic imagery of exclusion used by Jesus to describe the fate of the derelict when the Kingdom comes” (p. 117). And he concedes that “the idea of an eternal punishment for the reprobate – in the sense not merely of a final penalty, but also of endlessly perduring torment – seems to have had a substantial precedent in the literature of the intertestamental period, such as 1 Enoch, and perhaps in some early schools of rabbinic thought” (Ibid.). But though he allows for the “possibility” of reading Christ’s words that way, he insists that there is “nothing in the gospels that obliges one to believe this” and says that we simply cannot make “any dogmatic pronouncements on the matter” (Ibid.). As I noted in a previous post, Hart also resorts to such agnosticism when dealing with passages in Revelation that don’t sit well with universalism.

Now, when you consider any one passage in isolation, you may or may not think the universalist can cobble together some sort of case. But the arguments are always strained, lawyerly in the worst sense of trying desperately to open up some loophole by which the obvious implication of the text might be escaped. (Again, see my previous post for discussion of some of the problems.) And when all the relevant scriptural passages are considered en masse, the idea that you can reconcile scripture with universalism just falls apart. The idea that none of the relevant passages should be taken at face value, and that the vast majority of readers have for two millennia been getting all of them that badly wrong, is just too silly for words. And that is, of course, why, as Hart admits, “just about the whole Christian tradition” (p. 81) has always rejected universalism.

But now the universalist speaks out of the other side of his mouth. Having cobbled together a tentative strained universalist reading of this passage, a tentative strained universalist reading of that passage, a tentative strained universalist reading of a third passage, and so on, he suddenly dumps the whole lot of these sophistries on you and pretends that they together amount to a demonstration that there is nothing in scripture that is incompatible with universalism. He pretends that the burden of proof is now on the critics of universalism to show otherwise. By such sleight of hand, what has always been considered heterodox is now presented as having the presumption in its favor, and what has always been considered orthodox is put on the defensive.

Thus do we have John Milbank matter-of-factly asserting: “Of course it is Edward Feser who is heterodox and not DB Hart.”

Yes, of course. And of course, we have always been at war with Eastasia.

Related posts:

July 22, 2020

Hart, hell, and heresy

Well, yikes, as the kids say. Hell hath no fury like David Bentley Hart with his pride hurt. At Eclectic Orthodoxy, he creates quite the rhetorical spectacle replying to my review of his book

That All Shall Be Saved

. In response, I’ll say only a little about the invective and focus mainly on the substance. Since there’s almost none there, that will save lots of time. And since Catholic Herald gave me only 1200 words to address the enormous pile of sophistries that is his book, I would in any case like to take this opportunity to expand on some of the points I could make in only a cursory way in the review. Hart’s response

Well, yikes, as the kids say. Hell hath no fury like David Bentley Hart with his pride hurt. At Eclectic Orthodoxy, he creates quite the rhetorical spectacle replying to my review of his book

That All Shall Be Saved

. In response, I’ll say only a little about the invective and focus mainly on the substance. Since there’s almost none there, that will save lots of time. And since Catholic Herald gave me only 1200 words to address the enormous pile of sophistries that is his book, I would in any case like to take this opportunity to expand on some of the points I could make in only a cursory way in the review. Hart’s response

First let me reply to the two substantive points Hart makes in his response. In my review, I noted that it was “centuries” after the time of Christ before universalism was floated within Christianity. Hart says I am wrong and cites as among “the earliest witnesses” (whether friendly or hostile to universalism) Gregory of Nyssa, Basil, Jerome, and Augustine – all fourth or fifth century writers. For the reader whose math is rusty, that would place them… centuries after the time of Christ. Of course, above all others we have to consider Origen, who was a third century writer. Which, if your math is still rusty, would put him… centuries after the time of Christ.

Hart misunderstands a criticism I raise against his views about free will. He writes:

[Feser] claims, for instance, that from my treatment of the nature of rational freedom I “infer that no one is culpable” for his or her wicked choices… Where on earth did he get this weird idea that I anywhere deny human culpability for sin?

But that is not what I said. What I said is that Hart infers, from the fact that as rational creatures we are made for God, that we are not culpable for “any choice against God,” specifically. That is to say, he infers that we cannot be culpable for a sin of the kind that would damn us, of the kind that would separate us from God forever. And that is indeed a major theme of his book (one he reaffirms in his reply to my review). I did not attribute to Hart the view that we are not culpable for anyof the sins we commit. To be sure, in my review, I did go on to say:

Furthermore, if a choice is non-culpable because it is irrational, how can we be culpable for any bad thing that we do (given that bad actions are always contrary to reason)?

But obviously, what I am saying here is that this is an unintended consequence of Hart’s arguments, not that it is a thesis he actually intends to affirm.

Hart puts heavy emphasis in his book on the irrationality of acting contrary to an end toward which our nature directs us. Of course, he is right about that much. The trouble is that he fallaciously reasons from this correct premise a mistaken conclusion about culpability, because he persistently fails to distinguish:

(a) an end the pursuit of which is in fact good for us, given our nature, and

(b) an end the pursuit of which we take to begood for us (whether it really is or not)

Now, acting against either (a) or (b) would be contrary to reason, but not in the same sense. In particular, a person might act against (b) because of confusion, duress, passion, or something else that clouds reason. And that can certainly affect culpability. For example, suppose that you say something extremely rude and uncalled for to your mother, because she just roused you from a deep sleep or because you are heavily medicated and not thinking straight. We would not hold you culpable for such behavior, because we know you weren’t thinking clearly. If you had been, you would never have done such a thing, because you yourself take it to be good to be respectful of your mother.

But suppose instead that you are fully awake, stone cold sober, and calm, but that you nevertheless say something extremely rude and uncalled for to your mother. Here we typically would regard you as culpable, and we might be even more inclined to do so if you refused to admit that you had done something wrong but tried to rationalize it. Now, here too you would be acting contrary to reason or irrationally, but not in the same way as in the first example. In particular, your act would in this case be contrary to reason in the sense that it conflicted with what is actuallygood (as opposed to what you’d fooled yourself into falsely thinking was good). But your act would not be irrational in the sense that it resulted from confusion, duress, passion, or other factors of the kind that prevent clear thinking. And that is why we would regard it as culpable.

Hart’s mistake is conflating these two sorts of case. He thinks that since choosing to reject God would be irrational in the sense in which any action that is contrary to (a) would be, it follows that it would be irrational in the sense that would mitigate culpability, as actions that are contrary to (b) often are. But that doesn’t follow. And this erroneous conflation would also entail that we would not be culpable for any bad action that we commit, since any bad action (and not just explicitly rejecting God) would be contrary to (a).

To forestall misunderstanding, let me again make it clear that I am not saying that Hart explicitly or knowingly makes these fallacious inferences. I am saying that his discussion of rationality and freedom implicitly and inadvertently trades on such fallacies. And that is one reason I said that his book is a “mess” philosophically.

Hart’s rhetoric

So much for the actual intellectual substance of Hart’s reply. The rest is vituperation of an intensity and repetitiveness that is unusual even for Hart. Judging from his replies to readers in the comments section, this owes primarily to the last paragraph of my review, which clearly has gotten under Hart’s skin. That is understandable – indeed, I knew that that paragraph would upset him, though that is not the reason I wrote it. I wrote it because what I say there is true, and because to have said anything milder would simply not have done justice to the gravity of Hart’s offense against orthodoxy, or to the danger his writings on this subject pose to souls.

I’ll come back to that later. I do want briefly to comment on Hart’s rhetoric before returning to more substantive matters. As to the content, it’s mostly not worth responding to. At this point we’re all used to Hart’s shtick about how stupid, ill-informed, unscholarly, untalented, morally depraved, etc. I and his other critics are compared to himself. Reading through this stuff, all you can do is tap your foot impatiently and think “Fine, whatever, let’s get to something interesting already.” I will confess to being a little annoyed by his repeated false accusation that I am a liar. I have many faults, but that is not one of them. I did read your book, David, every word. It was my bedtime reading for a couple of weeks. Ask my poor wife, who had to endure a new and more violent expletive every time I turned another page and encountered yet another fallacy. (“What, do you have Tourette’s?” “No, it’s DBH.” “Ah.”)

Anyway, here’s the more important point that must be made about Hart’s rhetoric. He and his fans like to pretend that when his critics object to it, what they are concerned about is etiquette. No, what we are concerned about is logic. Hart and his admirers are so inured to his reliance on the ad hominem that they seem unable to perceive just how much of the heavy lifting it is doing in his writings, and how manifestly sophistical it looks to those outside the fan club.

Again and again in That All Shall Be Saved, complex philosophical and theological lines of argument are casually brushed aside after at most a cursory analysis, on the grounds that only “thorough conditioning,” “self-deception,” “collective derangement,” “emotional pressure,” “willful[ness]” and the like could get anyone to take them seriously (pp. 18-19, 45). A Thomist line of thought is breezily dismissed as “not ris[ing] to the level of the correct or incorrect” and “utterly devoid of so much as a trace of compelling logical content,” and thus something which “can recommend itself favorably only to a mind that has already been indoctrinated” and “been prepared by a long psychological and dogmatic formation to accept ludicrous propositions without complaint if it must” (pp. 20-21).

Yet other ideas are said to be not worth taking seriously because they have “less to do with genuine logical disagreement than with the dogmatic imperatives to which certain of the disputants feel bound,” or “because it is what they want to believe” (p. 28). Views Hart disagrees with are alleged to reflect only the “naïve religious mind at its most morally obtuse” (p. 12), are claimed to attract only those inclined to “accept… moral idiocy as spiritual subtlety” (p. 19), or are said to reflect “a picture of reality that… [is] morally corrupt, contrary to justice, perverse, inexcusably cruel, deeply irrational, and essentially wicked” (p. 208). And so on, and on and on and on.

This is, of course, exactly the sort of relentless question-begging ad hominem abuse one sees in every dime store New Atheist tract. Whether it is Richard Dawkins or David Bentley Hart, the basic rhetorical tactic is the same: The arguments are too awful to be worth considering in any detail, because the people giving them are so stupid and dishonest; and we know that these people are stupid and dishonest because they give arguments that are too awful to be worth considering in any detail.

And whether it is Dawkins or Hart, the problem with this is not that it is rude. The problem is that it is a merry-go-round of circular reasoning.

Pantheism?

In my review, I noted that a couple of Hart’s arguments imply a position that “is hard to distinguish from a pantheism that blasphemously deifies human beings.” In his response, Hart takes exception to this charge, though curiously, he does not tell us exactly how I’ve misinterpreted the remarks from his book that I cited as evidence. Let me now quote the relevant passages at greater length. I am going to highlight certain especially important lines, but please read each excerpt in it’s entirely for context. First, here is a passage in which Hart approvingly cites a view he attributes to Gregory of Nyssa:

Such is the indivisible solidarity of humanity, he argues, that the entire body must ultimately be in unity with its head, whether that be the first or the last Adam. Hence Christ’s obedience to the Father even unto death will be made complete only eschatologically, when the whole race, gathered together in him, will be yielded up as one body to the Father…

For Gregory, then, there can be no true human unity, nor even any perfect unity between God and humanity, except in terms of the concrete solidarity of all persons in that complete community that is, alone, the true image of God…

Apart from the one who is lost, humanity as God wills it could never be complete, nor even exist as the creature fashioned after the divine image; the loss of even one would leave the body of the Logos incomplete, and God’s purpose in creation unaccomplished…

I am not even sure that it is really possible to distinguish a single soul in isolation as either saint or sinner in any absolute sense . (pp. 142-44)

I will put to one side for present purposes the question of whether Hart has interpreted Gregory correctly. The point is that Hart clearly accepts the views he describes. A few pages later he makes the following further remarks:

We belong, of necessity, to an indissoluble coinherence of souls. In the end, a person cannot begin or continue to be a person at all except in and by way of all other persons… Yes, the psychological self within us – the small, miserable empirical ego that so often struts and frets its hour upon the stage of this world – is a diminished, contracted, limited expression of spirit, one that must ultimately be reduced to nothing in each of us if we are to be free from what separates us from God and neighbor; but the unique personality upon which that ego is parasitic is not itself merely a chrysalis to be shed. There may be within each of us (indeed, there surely is) that divine light or spark of nous or spirit or Atman that is the abiding presence of God in us… but that light is the one undifferentiated ground of our existence, not the particularity of our personal existences in and with one another. As spiritual persons, we are dynamic analogies of the simplicity of the divine life of love, and so belong eternally to that corporate identity that is, for Gregory of Nyssa, at once the “Human Being” of the first creation and also the eternal body of Christ.

But, then, this is to say that either all persons must be saved, or none can be. (pp. 154-55)

End quote. I think it should be obvious why these passages imply a kind of mitigated pantheism that collapses the distinction between God and the human race (even if they don’t go the whole hog of collapsing the distinction between God and the world in general).

In the first passage, Hart treats the entire human race as one big blob that only collectively makes up “the body of the Logos,” and without every single part of which Christ’s obedience to the Father is “incomplete.” This implies that the second Person of the Trinity is incarnate not just in the individual human being Jesus of Nazareth, but in the entire human race considered as one lump. What else could it mean to say that only all human beings together make up “the body of the Logos”? How could Christ’s obedience to the Father be incomplete apart from universal salvation, unless all human beings collectivelymake up his human nature?

In the second passage, Hart tells us that the individual ego must be “reduced to nothing” and that what will remain is a “divine light” or “Atman” that is to be identified with “the one undifferentiated ground of our existence, not the particularity of our personal existences in and with one another.” That sounds pretty much like Vedantic pantheism, right down to the term “Atman.”

Perhaps Hart would say that I am taking his colorful language too literally. The problem with that response, though, is that unless this language is taken literally, it will fail to do what Hart wants it to do, namely serve as an argument for universalism. The first passage will support universalism only if every single human being is literally part of Christ’s body, so that Christ’s human nature cannot be fully obedient to the Father unless every single human being is ultimately obedient. The second passage will support universalism only if every single human being is part of one big lump that is in turn literally identical with the divine nature.

I don’t know if Hart intends to blur the distinction between God and human beings. It is possible that he is simply reasoning in a sloppy way and doesn’t see the implication of what he is saying. I am claiming only that his argument does have that implication, or at least that if it does not, he owes us an explanation of how he can avoid it. This is another reason his book is a “mess” from a philosophical point of view.

Analogy and goodness

One of the big themes of Hart’s book is the problem he thinks the analogical approach to theological language – which, of course, we Thomists are very keen on – poses for the doctrine of eternal damnation. For if God allows anyone to suffer everlastingly, how can he be good in a sense that is truly analogous to the goodness we attribute to human beings?

Hart thinks this is a devastating objection, but in fact it can be answered fairly quickly. The crucial issue here isn’t really analogy, but goodness. And in fact it isn’t even goodness in general, but the goodness of punishment, specifically. As writers on the controversy over the doctrine of hell often point out, universalists and defenders of the doctrine typically operate with two very different conceptions of the purpose of punishment, each of which can be independently motivated. A retributive conception of punishment takes the fundamental end of punishment to be the restoration of the right order of things by the infliction of just deserts, even though there are other ends as well. By contrast, a rehabilitation-centered view of punishment sees the reform of the offender as the fundamental end, even though it too might recognize other ends.

Now, if you see punishment as fundamentally a matter of rehabilitation, then it is understandable why you would think that everlasting punishment cannot be a good form of punishment. For such punishment, being everlasting, will never yield rehabilitation. By contrast, if you see retributionas the fundamental end of punishment, then everlasting punishment can be good, if the offender really has done something to deserve it.

What sort of offense could deserve it? The traditional Thomist view, which I have defended elsewhere (see the posts linked to below), is that at death the will of an offender can be locked onto evil in such a way that a damned soul perpetually, freely chooses bad actions. And it thereby merits perpetual punishment.

You may or may not think this view is at the end of the day plausible, but the point is that if it is correct, and if the retributive view of punishment is also correct, then there is indeed an analogy between the goodness that human beings exhibit when they inflict deserved punishments, and the goodness God exhibits when he inflicts everlasting punishment. So, contra Hart, it isn’t really analogy per se that is the key issue here, but rather the retributive theory of punishment and the Thomist account of the fixity of the postmortem soul.

Again, see the links below for more on the Thomist account of the soul’s fixity after death; and see By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed for a defense of the retributive theory of punishment.

The parallelism problem

Hart has nothing to say in response to the scriptural arguments I gave in my review, other than a hand-waving appeal to authority, especially his own authority. This is, of course, another part of Hart’s standard shtick. When backed into a corner on patristic or scriptural matters, he will always tell you just to shut up and listen to what the experts say, or at least to what the “real” experts (i.e. the ones who agree with him) have to say, or – let’s cut to the chase – to what his favorite expert (DBH himself) has to say. This has exactly the same probative value as an argument of mine would have if I rested it on my authority as a philosopher – namely, none at all. It’s a rhetorical ploy to impress the rubes, that’s all.

Now, the scriptural basis of the doctrine of hell is a big topic, and for present purposes I will make just a few points. Consider first what I’ll call the parallelism problem for attempts, like Hart’s, to argue that scriptural passages making reference to “everlasting punishment” and the like are better translated as warning only of punishments to last “for the age.” The problem is that if the translation is consistent, then we will have to say that the reward of the just is no more everlasting than the punishment of the wicked is. For example, Matthew 25:45-46 says:

Then he shall answer them, saying: Amen I say to you, as long as you did it not to one of these least, neither did you do it to me. And these shall go into everlasting punishment: but the just, into life everlasting. (Douay-Rheims translation)

The same word (aionion) is translated “everlasting” in each case. Hence if we deny that Christ is really threatening the wicked with everlasting punishment, then to be consistent, we also have to deny that he is promising everlasting life to the righteous. This is a very old objection; Augustine, for example, puts great emphasis on it. For that reason, I am sure that Hart and his fans will be inclined to dismiss it as old hat, if they deign to respond to it at all. What matters, though, is whether it is correct, and Hart gives us no reason at all to doubt that it is.

The parallelism problem crops up in Revelation as well. For example, Revelation 4:9-10 says:

And when those living creatures gave glory, and honour, and benediction to him that sitteth on the throne, who liveth for ever and ever; the four and twenty ancients fell down before him that sitteth on the throne, and adored him that liveth for ever and ever.

And Revelation 10:5-6 says:

And the angel, whom I saw standing upon the sea and upon the earth, lifted up his hand to heaven, and he swore by him that liveth for ever and ever, who created heaven, and the things which are therein; and the earth, and the things which are in it; and the sea, and the things which are therein.

Meanwhile, Revelation 14:9-11 says:

And the third angel followed them, saying with a loud voice: If any man shall adore the beast and his image, and receive his character in his forehead, or in his hand; he also shall drink of the wine of the wrath of God, which is mingled with pure wine in the cup of his wrath, and shall be tormented with fire and brimstone in the sight of the holy angels, and in the sight of the Lamb. And the smoke of their torments shall ascend up for ever and ever: neither have they rest day nor night, who have adored the beast, and his image, and whoever receiveth the character of his name.

And Revelation 20:9-10 says:

And there came down fire from God out of heaven, and devoured them; and the devil, who seduced them, was cast into the pool of fire and brimstone, where both the beast and the false prophet shall be tormented day and night for ever and ever.

Now, if you are to deny that the latter two passages really describe punishment of the wicked that will last “for ever and ever,” then to be consistent you will also have to deny that the first two passages describe God as living and receiving adoration “for ever and ever.”

Now, Hart’s method for dealing with Revelation in general is to feign agnosticism. That particular book, he claims, is so filled with allegory and apocalyptic imagery that we just can’t know what it is really saying (pp. 107-8).

But there are a couple of problems with this dodge. For one thing, Hart is guilty of special pleading. As longtime readers know, where the topic of whether there will be animals in the afterlife is concerned, Hart insists that we know perfectly well what eschatological passages from scripture mean, and that they must be given a literal reading. Yet oddly, when such a reading would conflict with his universalism, he throws up his hands and says “Gee, who can know what passages like that are really saying?”

For another thing, not every passage in Revelation is equally obscure. Yes, it is not always easy to discern the significance of the book’s symbolic references to, say, locusts arising from a bottomless pit, or a whore riding a scarlet beast. But various other specific passages are clear enough, as is the general theme of the final victory of the saints and the final defeat of the wicked. It is simply not plausible to claim that the references in Revelation 14 and 20 to the everlasting punishment of the wicked are any more obscure than the references in Revelation 4 and 10 to the everlasting life of God.

Another move some universalists have made is to bite the bullet and affirm that the reward of the just is not, after all, any more everlasting than the punishment of the wicked. But there are a couple of problems with this move too. First, it is simply not a natural reading of passages like the ones from Matthew and Revelation, which are clearly intended to tell us, with finality, how the human story ends. No one without a universalist axe to grind could possibly read them and come away thinking that they are merely telling us: “The righteous will be given a reward that lasts for a long time – a whole age!– but, you know, who knows what will happen after that?”

Secondly, the “bite the bullet” strategy simply won’t work for passages like the ones from Revelation 4 and 10. It would be quite absurd to suggest that Revelation is telling us only that the deity will live to a ripe old age.

The teaching of Christ

Matthew 25:46 gives us only one example of how much less reassuring the Christ of scripture is than the Christ who exists in Hart’s imagination. Consider Matthew 12:31-32:

Therefore I say to you: Every sin and blasphemy shall be forgiven men, but the blasphemy of the Spirit shall not be forgiven. And whosoever shall speak a word against the Son of man, it shall be forgiven him: but he that shall speak against the Holy Ghost, it shall not be forgiven him, neither in this world, nor in the world to come.

Now, exactly what this “unpardonable sin” amounts to requires analysis, but for present purposes what matters is that Christ tells us that there is such a thing. But Harttells us that there is not. Why should we believe Hart over Christ? Or if Hart were to tell us that Christ didn’t really mean it, why on earth should we believe that? As I said in my review, Hart makes Christ more “merciful” at the cost of making him incompetent. Hart insists that the true Gospel is that all will in fact be saved, indeed must in fact be saved. Yet Christ, his divinity notwithstanding, was somehow so tongue-tied that he not only never managed to say this himself, but actually said things that imply the opposite!

Then there is Christ’s famous remark about Judas, which in my opinion is the single most chilling thing anyone has ever said: “Woe to that man by whom the Son of man shall be betrayed: it were better for him, if that man had not been born” (Matthew 26:24). Now, you have to strain things very greatly to try to escape the conclusion that Judas is damned. The way some try to do this is to read Christ’s words as a warning to Judas rather than a description of his actual fate. I don’t think that is plausible, but even if it were, it does not help the universalist. Indeed, the “warning” interpretation presupposes the falsity of universalism. Christ could hardly be warning Judas of eternal damnation if eternal damnation was not even possible in the first place!

The bottom line is this. If universalism were true, then it could not possibly be true of any human being that it would be better for him not to be born. But Christ tells us that it is at least possible for someone to be in so sorry a state that it would have been better for him not to be born. And once again, even if Hart were to cobble together some strained reading in order to wriggle out of this conclusion, he would only succeed once again in making Christ out to be so incompetent that he says things whose face value meaning is precisely the opposite of what he really intends.

Hart’s heresy

As I said in my review, Catholic readers in particular simply cannot avoid the conclusion that Hart’s position is heretical. Hart is not merely taking the annihilationist position that the wicked will be entirely destroyed rather than suffering forever, and he is not even taking the Balthasarian position that we can hopethat all are saved. He makes the much stronger claim that in fact all will and indeed must be saved, and that if Christianity cannot be reconciled with this universalist thesis, then Christianity must be rejected. As I showed in my review, this extreme position is one that the Church has unambiguously condemned.

But it isn’t just Catholics who should be alarmed by Hart’s approach. Christianity claims to be grounded in a special divine revelation. Christians disagree over where this revelation is to be found. For Protestants, it is to be found in scripture alone. For Eastern Orthodoxy, it is to be found in scripture as understood in light of tradition. For Catholics, it is to be found in scripture and tradition as interpreted by the Magisterium of the Church. Christians often disagree about what scripture, tradition, and Magisterium actually say, i.e. about whether such-and-such a teaching is in fact authoritatively taught in one of these sources. But they would agree that if something really is taught by one of the authoritative sources, then we must assent to it. To reject the source itself (again, whether one conceives of this as scripture, or scripture plus tradition, or scripture plus tradition plus Magisterium) is just to reject the authority of the purported revelation, and thus to reject Christianity.

Now, Hart freely admits in That All Shall Be Savedthat he is at odds with “just about the whole Christian tradition” (p. 81). His ultimate appeal is to “conscience,” against which “the authority of a dominant tradition… has no weight whatever” (p. 208). This not only goes beyond the Protestant and Orthodox rejection of the authority of the Magisterium, but beyond the Protestant rejection of the authority of tradition. It is not even scripture alone that trumps all else, but DBH’s conscience alone. And his conscience demands that Christianity conform itself, not merely to some personal theological opinion of his, but to an opinion that has traditionally been regarded as heretical! He is calling on his brethren, not to return to traditional teaching, as St. Vincent of Lerins would, but rather to abandon it, indeed to repent of it as if it were something of which the Church should be ashamed.

That Hart denies that this shows any arrogance on his part (p. 208) demonstrates only that he is delusional as well as arrogant. Though on a particular point of doctrine he aligns with Origen, in spirit they could not be farther apart. As the Catholic Encyclopedia says of Origen, despite his errors:

He warns the interpreter of the Holy Scripture, not to rely on his own judgment, but “on the rule of the Church instituted by Christ”. For, he adds, we have only two lights to guide us here below, Christ and the Church; the Church reflects faithfully the light received from Christ, as the moon reflects the rays of the sun. The distinctive mark of the Catholic is to belong to the Church, to depend on the Church outside of which there is no salvation; on the contrary, he who leaves the Church walks in darkness, he is a heretic. It is through the principle of authority that Origen is wont to unmask and combat doctrinal errors. It is the principle of authority, too, that he invokes when he enumerates the dogmas of faith. A man animated with such sentiments may have made mistakes, because he is human, but his disposition of mind is essentially Catholic and he does not deserve to be ranked among the promoters of heresy.

How very far from this attitude is Hart, whose own version of “Here I stand” would embarrass even Luther. It is bad enough that he lulls Christians into a deadly complacency vis-à-vis their eternal salvation. He also teaches, by example, an impudence with respect to the tradition that is simply incompatible with a solemn affirmation of Christianity as a revealed religion. These are in no way intended as insults, but simply as a straightforward summary of the facts as I see them. And that is the reason for the harshness of the final paragraph of my Catholic Heraldreview. It was, I believe, well-deserved.

Much more could be said, and I have already said much of it in earlier posts, which develop lines of argument (such as the Thomistic argument concerning the fixity of the will after death) that Hart glibly dismisses, rather than offering a serious response. I direct the interested reader to them. Lasciate ogni speranza voi ch′entrate:

How to go to hell

Does God damn you?

Why not annihilation?

A Hartless God?

No hell, no heaven

July 20, 2020

The experts have no one to blame but themselves

The Week’s Damon Linker frets aboutthe state of the “American character,” citing an emergency physician’s wife he knows whose friends ignore her frantic pleas on Facebook to take COVID-19 more seriously. The Hill reports that the “experts” are exasperated that people aren’t responding to their warnings about the virus with sufficient urgency.

The Week’s Damon Linker frets aboutthe state of the “American character,” citing an emergency physician’s wife he knows whose friends ignore her frantic pleas on Facebook to take COVID-19 more seriously. The Hill reports that the “experts” are exasperated that people aren’t responding to their warnings about the virus with sufficient urgency. Well, of course they aren’t, because so many experts, journalists, and politicians have, on this subject, proven themselves to be completely full of it. Hypocrisy and lies

There are several illustrations of this, and everyone knows Exhibit A. After weeks of peddling panic about the supposedly grave dangers of mass gatherings, many of these experts, journalists, and politicians suddenly decided a few weeks ago that having thousands of left-wing protesters packed together in the streets, across the country and for days, was just fine.

This rather gave the game away – not because these experts, journalists, and politicians don’t care about the lives of left-wing protesters, but precisely because they do care. They hardly want hordes of fellow left-wingers dropping dead or confined to hospital beds, especially not when there is political hay to be made by having them riled up.

People aren’t completely stupid. They can draw the obvious conclusion – that the experts, journalists, and politicians who approved of the protests don’t really believe that people in the age range and with the health status of the typical protester are in serious danger from the virus.

Hypocrisy isn’t a good reason to reject an argument, but it is an excellent reason to reject testimony. If people offer advice about matters of safety that they don’t hold even their own friends to, you can be sure they don’t really believe it. The jig is up. Telling everyone now to get back inside again sounds at this point like “Pay no attention to that man behind the curtain.”

Meanwhile, the sainted Dr. Anthony Fauci tells us that he and other officials were lying when they initially said that face masks were unnecessary – and then in the next breath complains that many people don’t trust scientific authorities like himself!

Crack immunologist though he is, Dr. Fauci is evidently no expert on logic or even basic human psychology, so let me spell it out for him: When you frankly tell people that you will lie to them when you think doing so is for their own good, they are bound to wonder whether your next remark is also a lie. Not only is this a natural psychological response, it is a good way to avoid a fallacy of Appeal to Authority. For as logicians teach, expert testimony should be taken with a grain of salt when there are grounds to doubt an expert’s objectivity. And any expert who admits that he is a liar is, I submit, giving us such grounds.

Biased reporting

It is now widely acknowledged that the virus poses a serious danger primarily to the elderly and those with serious preexisting medical conditions. Yes, occasionally there are people who fall outside those categories who also get seriously ill, but that’s true of other illnesses that we don’t respond to with lockdowns and other draconian measures.

So why the hell do people other than those at risk have, at this point, radically to disrupt their lives and livelihoods? Why not just quarantine those who are sick or especially vulnerable? Suspicion that there simply is no convincing answer to this question is only reinforced by the blatant dishonesty in much reporting about the virus. For example, the evidence shows that children are simply not in any significant danger of getting ill from the virus or of spreading it – a now viral recent NBC news video with a group of pediatricians providing some vivid expert testimony to that effect. Yet the Hillarticle linked to above, despite essentially acknowledging this, still strains desperately to find a way to scare us into thinking that we just might end up killing the kiddies if we reopen schools. Which is true in the same sense that you just might kill the kiddies if you take them out on the freeway or let them go swimming.

Linker’s dishonesty is even more shameless. He writes:

I remember when trusted models were predicting a total of 100,000 deaths from the pandemic. Skeptics dismissed this as scaremongering. Then the estimates were lowered to 60,000 deaths and the skeptics scoffed: "We wrecked the economy for this? It's just the flu!" That was three months ago. On Wednesday of this week, we surpassed 140,000 dead.

Well, here’s what I remember: the notorious Imperial College model’s prediction that we could see over 2 million deaths in the U.S., and similar doomsday scenarios from others. I doubt Linker has really forgotten that part, but certainly millions of other people have not. And that, of course, is another reason they are skeptical now. They would be insane not to be. Linker should worry less about the “American character” and more about the character of experts and politicians – and of journalists like himself, who apparently thinks that his readers are all Mementocases who will buy his ridiculous insinuation that the experts were lowballing the death rate four months ago.

Then there is the manifestly politicized nature of much of the coverage. The crisis has been far worse in “blue states” than in “red states,” and yet the press routinely demonizes Republican governors and lionizes Democratic governors. The most ridiculous example is the hagiographic treatment afforded New York governor Andrew Cuomo, whose administration’s policy of forcing infected elderly people back into nursing homes is responsible for thousands of deaths. Had Donald Trump done such a thing, we would now be subjected to yet another impeachment jihad. Last week, the stench of this BS finally got to be too much even for CNN’s Jake Tapper.

When journalists transparently act like people who want to push a narrative rather than disinterested pursuers of truth, they can hardly complain when people respond accordingly.

Lack of common sense

It so happens that the politicians and journalists most inclined to push for draconian policies for dealing with the virus also tend to be those most inclined to minimize or excuse the behavior of looters and rioters, to call for police to stand down rather than prevent such violence, to call even for defunding the police, and to endorse other similarly insane and depraved notions.

Well, here’s the thing. Suppose some authority makes it clear that he is not interested in doing what is necessary to keep your business from being looted or burnt down, or to keep your neighborhood safe. You will naturally conclude that he is lacking in good judgment and good will.

Hence, when he also advocates policies for dealing with the virus that threaten to destroy your livelihood, to prevent your children from being properly educated, etc., you are, if you are a rational person, going to doubt that he really has your best interests at heart or is capable of making sound policy decisions. You will not be confident that he can wisely handle a complex thing like a pandemic, when he has shown himself unreliable on a simple thing like the fundamental duty of government to protect life, liberty, and property.

Nor are the policies prima facie any better than the politicians peddling them. Indefinite lockdowns are as untried, untested, and contrary to common sense as defunding the police. The Hong Kong flu pandemic of 1968-69 killed over 1 million people worldwide, and 100,000 in the United States alone. The virus was a danger primarily to older people. In short, the situation was not dissimilar to the current crisis. Yet there was no drama queen hysteria, no confinement of the whole country to house arrest, no massive infringement on the natural right of citizens to earn a livelihood. The idea of dealing with a pandemic by indefinitely locking down a whole state or a whole country – as opposed to merely quarantining those who are sick or at high risk – is an ivory tower construct that is only about fourteen years old.

Even in our degenerate age, many people retain enough common sense to see that they are being presented with a false alternative. They are capable of taking the virus seriously while balking at needlessly extreme measures for dealing with it. And their skepticism is bound only to increase when it is met, not with dispassionate arguments, but with shrill accusations of being “COVID deniers” or “anti-science,” from people many of whom can for independent reasons be judged to lack common sense.

Even if the most dire warnings currently being issued by experts, politicians, and journalists were well-founded – which, at this point, I personally don’t believe for a minute – the latter can only blame themselves if more people don’t heed them.

Related posts:

What “the science” is saying this week

The lockdown is no longer morally justifiable

The lockdown and appeals to authority

The burden of proof is on those who impose burdens

The lockdown’s loyal opposition

Some thoughts on the COVID-19 crisis

Computer campus

As you know, academic life has largely gone online this year. My own classes at Pasadena City College this fall will be entirely online.

As you know, academic life has largely gone online this year. My own classes at Pasadena City College this fall will be entirely online.The Thomistic Institute has also adapted to the circumstances with its series of online Quarantine Lectures. I will be giving one of them this Thursday, July 23, on the topic “The Metaphysics of the Will.” Details here.

July 17, 2020

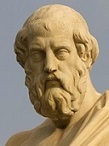

Plato predicted woke tyranny

What we are seeing around us today may well turn out to be a transition from decadent democratic egalitarianism to tyranny, as Plato described the process in The Republic. I spell it out in a new essay at The American Mind.

What we are seeing around us today may well turn out to be a transition from decadent democratic egalitarianism to tyranny, as Plato described the process in The Republic. I spell it out in a new essay at The American Mind.

July 13, 2020

Review of Hart

My review of David Bentley Hart’s

That All Shall Be Saved: Heaven, Hell, and Universal Salvation

appears in the latest issue of Catholic Herald. You can read it online here. (It’s behind a paywall, but when you click on the link you will see instructions telling you how to register for free access.)

My review of David Bentley Hart’s

That All Shall Be Saved: Heaven, Hell, and Universal Salvation

appears in the latest issue of Catholic Herald. You can read it online here. (It’s behind a paywall, but when you click on the link you will see instructions telling you how to register for free access.) Here are some earlier posts that explore in greater detail some of the issues raised in the review: How to go to hell

Does God damn you?

Why not annihilation?

A Hartless God?

No hell, no heaven

Speaking (what you take to be) hard truths ≠ hatred

Damnation denialism

July 8, 2020

Other minds and modern philosophy

The “problem of other minds” goes like this. I have direct access to my own thoughts and experiences, but not to yours. I can perceive only your body and behavior. So how do I know you really have any thoughts and experiences? Maybe you merely behave as if you had them, but in reality you are a “zombie” in the philosophy of mind sense, devoid of conscious awareness. And maybe this is true of everyone other than me. How do I know that any minds at all exist other than my own? One traditional answer to the problem is the “argument from analogy.” I know from my own case that when, for example, I flinch and cry out upon injury, there is a sensation of pain associated with this behavioral reaction, and that when I say things like “It’s going to rain” that’s because I have the thought that it is going to rain. So, by analogy, I can infer from the fact that you also flinch and cry out, and also say things like “It’s going to rain,” that you too must have thoughts and sensations of pain. In modern philosophy this argument is put forward by writers like John Stuart Mill, and it is sometimes suggested that one can find something like it in Augustine’s On the Trinity, Book 8, Chapter 6.

The “problem of other minds” goes like this. I have direct access to my own thoughts and experiences, but not to yours. I can perceive only your body and behavior. So how do I know you really have any thoughts and experiences? Maybe you merely behave as if you had them, but in reality you are a “zombie” in the philosophy of mind sense, devoid of conscious awareness. And maybe this is true of everyone other than me. How do I know that any minds at all exist other than my own? One traditional answer to the problem is the “argument from analogy.” I know from my own case that when, for example, I flinch and cry out upon injury, there is a sensation of pain associated with this behavioral reaction, and that when I say things like “It’s going to rain” that’s because I have the thought that it is going to rain. So, by analogy, I can infer from the fact that you also flinch and cry out, and also say things like “It’s going to rain,” that you too must have thoughts and sensations of pain. In modern philosophy this argument is put forward by writers like John Stuart Mill, and it is sometimes suggested that one can find something like it in Augustine’s On the Trinity, Book 8, Chapter 6.The standard objection to this argument is that it amounts to the weakest possible kind of inductive inference, a generalization from a single instance to every member of a class. There are eight billion people, and I have observed in only one case, namely my own, a correlation between thoughts and experiences on the one hand and bodily properties and behavior on the other. So how does the inference from my own case to the rest of the human race not amount to a fallacy of hasty generalization?

But the idea that there is a “problem” here, and that the solution to it is a kind of inductive generalization, are artifacts of modern philosophical assumptions. I don’t think Augustine was in fact giving an “argument from analogy” in the sense in which modern philosophers have done. He was not offering a philosophical theory in response to a philosophical problem. He was just noting how, in his view, we do in fact in everyday life know that other minds exist. Here is the relevant passage:

For we recognize the movements of bodies also, by which we perceive that others live besides ourselves, from the resemblance of ourselves; since we also so move our body in living as we observe those bodies to be moved. For even when a living body is moved, there is no way opened to our eyes to see the mind, a thing which cannot be seen by the eyes; but we perceive something to be contained in that bulk, such as is contained in ourselves, so as to move in like manner our own bulk, which is the life and the soul. Neither is this, as it were, the property of human foresight and reason, since brute animals also perceive that not only they themselves live, but also other brute animals interchangeably, and the one the other, and that we ourselves do so. Neither do they see our souls, save from the movements of the body, and that immediately and most easily by some natural agreement. Therefore we both know the mind of any one from our own, and believe also from our own of him whom we do not know. For not only do we perceive that there is a mind, but we can also know what a mind is, by reflecting upon our own: for we have a mind.

End quote. Note that Augustine attributes to non-human animals the same kind of knowledge that other things are alive (and, presumably, conscious too) that he attributes to us. But non-human animals do not engage in inductive reasoning. So, it isn’t an inductive generalization, fallacious or otherwise, that he is attributing to us either.

I submit that there are at least three assumptions more typical of modern philosophy than of ancient and medieval philosophy that underlie the idea that there is such a thing as a “problem of other minds,” and that our knowledge of other minds is grounded in a kind of inductive generalization.

The first is that genuine knowledge is always a kind of “knowing that” or propositional knowledge, as opposed to a kind of “knowing how” or tacit knowledge. (See Aristotle’s Revenge , pp. 95-113 for discussion of this distinction.) Not all modern philosophers take this view, but it is criticized by thinkers like Wittgenstein, Heidegger, Michael Polanyi, Hubert Dreyfus, et al. as typical of a Cartesian conception of rationality. The idea is that knowledge can always be analyzed into the possession of explicitly formulated propositions and inferences. If ordinary people don’t seem consciously to be entertaining such propositions and inferences, then it is sometimes claimed in response that the propositions and inferences are nevertheless present below the level of consciousness (say, as the rules and representations of a computer program implemented in the brain).

It is natural, on this model of rationality, to think that knowledge of other minds must involve some kind of inference. Wittgenstein’s critique of the whole debate over the problem of other minds might be read as claiming that knowledge of other minds is in fact a kind of tacit knowledge rather than a propositional or inferential kind of knowledge. On this view, the debate simply misunderstands the nature of our knowledge in this case.

A second relevant modern assumption is that there is a metaphysical gap between matter and consciousness that makes inferring the presence of the latter from facts about the former inherently problematic. The standard modern conception of matter inherited from the early modern “mechanical philosophy” facilitates this assumption. Matter is taken to be characterized by quantifiable primary qualities alone (size, shape, motion, etc.) and lacking anything like qualitative secondary qualities (color, sound, heat, cold, etc.), at least as common sense understands them. Hence it becomes mysterious how the qualia of conscious experience could be material, and knowledge of a thing’s material properties comes to seem insufficient to ground an inference to its having any mental properties. (This is, of course, a topic about which I’ve written many times.)

A third relevant assumption – and the one I want to focus on here – involves what we might call a Baconian conception of our knowledge of the natures of things, as opposed to an Aristotelian conception. For the Aristotelian-Scholastic position against which Francis Bacon reacted, common sense is more or less right about the natures of everyday natural objects, even if it isn’t very sophisticated. The ordinary observer correctly grasps what it is to be a stone, a tree, or a dog, even if it takes scientific investigation to understand these natures in a deeper and more sophisticated way. On this view, the senses are, you might say, friendly witnesses and just need an expert to ask the right questions in order to find out what else they know.

For Bacon, by contrast, the real natures of things are hiding behind false appearances, and sense experience is a hostile witness who must be tricked and threatened into revealing what it knows. Hence Bacon’s emphasis on slow and painstaking observations under artificial conditions, and the gradual working up from them to a general conclusion before one can claim to know what a thing of a certain kind is really like.

Also relevant is the modern idea that understanding the physical world is not a matter of uncovering the essences of things, but rather a matter of identifying the laws that relate observed phenomena. This involves formulating a general theory, deriving predictions from it, and then testing those predictions by way of a series of observations and experiments.

If that is the way that knowledge of the empirical world works, then naturally it comes to seem that whether other people really have minds is not as clear-cut as common sense supposes, and some kind of theoretical inference must be deployed in order to justify the supposition that they do. The meagerness of the evidential base in one’s own case in turn becomes a major problem, insufficient as it is for the construction of a Baconian inference.

Now, as contemporary neo-Aristotelian philosophers of science point out, this is not exactly how science in fact typically proceeds. To be sure, the Baconian emphasis on making observations under artificial experimental conditions certainly does feature in modern scientific method, but the idea of piling up instances before drawing a general conclusion does not. As Nancy Cartwright has argued, once the right experimental conditions are set up, multiple observations are not seen as necessary. She writes: “Modern experimental physics looks at the world under precisely controlled or highly contrived circumstance; and in the best of cases, one look is enough. That, I claim, is just how one looks for [Aristotelian] natures” (The Dappled World, p. 102, emphasis added).

Now, if few observations or even a single observation are all that is needed when the circumstances are right, then we have an essentially Aristotelian rather than Baconian approach to how many cases are needed in order to determine the basic nature of a thing. The difference is in the nature of the cases, not the numberof cases. The Aristotelian thinks that ordinary observation isn’t especially liable to get the nature of a thing positively wrong (even if it does not go very deep either) whereas the Baconian thinks that ordinary observation’s getting things positively wrong is a serious possibility.

Now, suppose the Baconian were correct about observation of things other than ourselves – stones, trees, dogs, etc. Suppose that common sense is indeed prone to getting the natures of these things wrong (which is, again, a stronger claim than just saying that common sense has only a superficial knowledge of their natures, which the Aristotelian would not deny).

Still, it wouldn’t follow that we are likely to get things wrong about our own nature, and prima facie that is unlikely, since in this case the knower and the thing known are the same. Of course, one could argue that there is a dramatic appearance/reality gap even here, but the point is that you would have to argue for such a claim. It is not prima facie what we would expect.

In that case, though, why couldn’t one know just from one’s own case that a physiology and behavior like ours go hand-in-hand with a psychology like ours as a matter of human nature? And then, applying this knowledge of human nature, why couldn’t one thereby know that other human beings too have mind’s like one’s own? “Problem of other minds” solved.

Again, some philosophers would of course argue that things are not as they seem even in the case of our apparent knowledge of our own minds. But the point is that that is simply not a plausible default assumption. There is a presumption in favor of our having a correct understanding of our own nature, and (given what I’ve just argued) there is, accordingly, a presumption in favor of other people having minds just like our own.

That suffices to undermine the idea that there is a frightfully difficult “problem of other minds.” The correct description of our situation is not that we don’thave good grounds for believing in other minds, and therefore have to cobble together some solution to this problem. It’s that we do have good grounds for believing that there are other minds, and therefore the philosopher who thinks otherwise can make things seem problematic only by making a number of tendentious modern (and, I would say, wrong) philosophical assumptions.

July 4, 2020

The virtue of patriotism

Patriotism involves a special love for and reverence toward one’s own country. These days it is often dismissed as sentimental, unsophisticated, or even bigoted. In fact it is a moral virtue and its absence is a vice. Aquinas explains the basic reason:

Patriotism involves a special love for and reverence toward one’s own country. These days it is often dismissed as sentimental, unsophisticated, or even bigoted. In fact it is a moral virtue and its absence is a vice. Aquinas explains the basic reason:A man becomes a debtor to others in diverse ways in accord with the diverse types of their excellence and the diverse benefits that he receives from them. In both these regards, God occupies the highest place, since He is the most excellent of all and the first principle of both our being and our governance. But in second place, the principles of our being and governance are our parents and our country, by whom and in which we are born and governed. And so, after God, a man is especially indebted to his parents and to his country. Hence, just as [the virtue of] religion involves venerating God, so, at the second level, [the virtue of] piety involves venerating one’s parents and country. Now the veneration of one’s parents includes venerating all of one’s blood relatives... On the other hand, the veneration of one’s country includes the veneration of one’s fellow citizens and of all the friends of one’s country. (Summa Theologiae II-II.101.1, Freddoso translation) Love and reverence for country is thus an extension of love and reverence for parents and family, and has a similar basis. One’s country is like an extended family, and benefits one in ways analogous to the benefits provided by family. Hence, just as one owes a special gratitude and respect to one’s own parents and family that is not owed to other families, so do does one owe a special gratitude and respect to one’s own country that is not owed to other countries.

But it’s not just what your country has done for you that matters, it’s what you can do for your country. As Aquinas also argues, just as one is obliged to provide benefits to one’s own family in a way one is not obliged to provide them to other families, so too ought one to give benefits to one’s own country that one does not owe to other countries. He writes:

Augustine says… “Since one cannot do good to all, we ought to consider those chiefly who by reason of place, time or any other circumstance, by a kind of chance are more closely united to us”…

Now the order of nature is such that every natural agent pours forth its activity first and most of all on the things which are nearest to it… But the bestowal of benefits is an act of charity towards others. Therefore we ought to be most beneficent towards those who are most closely connected with us.

Now one man's connection with another may be measured in reference to the various matters in which men are engaged together; (thus the intercourse of kinsmen is in natural matters, that of fellow-citizens is in civic matters, that of the faithful is in spiritual matters, and so forth): and various benefits should be conferred in various ways according to these various connections, because we ought in preference to bestow on each one such benefits as pertain to the matter in which, speaking simply, he is most closely connected with us…

For it must be understood that, other things being equal, one ought to succor those rather who are most closely connected with us. (Summa Theologiae II-II.31.3)

As Aquinas also says, by no means does this entail that one has no obligations to help those of other countries, any more than one’s special duty to one’s own parents and family entails that one need not ever help other families. The point is just that a special concern for one’s own country and countrymen is not only not wrong, it is obligatory. As one work of Catholic moral theology says:

Piety is owed to parents and country as the authors and sustainers of our being… On account of this nobility of the formal object, filial piety and patriotism are very like to religion and rank next after it in the catalogue of virtues…

Country should be honored, not merely by the admiration one feels for its greatness in the past or present, but also and primarily by the tender feeling of veneration one has for the land that has given one birth, nurture, and education… External manifestations of piety towards country are the honors given its flag and symbols, marks of appreciation of its citizenship… and efforts to promote its true glory at home and abroad. (McHugh and Callan, Moral Theology, Volume II, pp. 412-13)

As with other virtues, the virtue of patriotism is a mean between extremes, and thus there are two corresponding vices, one of excess and one of deficiency. Here is how a couple of standard works of moral theology in the Thomistic tradition describe the first vice:

Excess is shown in this virtue by those who cultivate excessive nationalism in word and deed with consequent injury to other nations. (Prümmer, Handbook of Moral Theology, p. 211)

Patriotism should not degenerate into patriolatry, in which country is enshrined as a god, all-perfect and all-powerful, nor into jingoism or chauvinism, with their boastfulness or contempt for other nations and their disregard for international justice or charity. (McHugh and Callan, Moral Theology, Volume II, p. 414)

As with the virtue of patriotism itself, the nature and unreasonableness of this vice of excess are best understood on analogy with the case of parents and family. Even most people with a deep sentimental attachment to their own parents and family would find it bizarre to suppose that this would entail deifying them, or justify hatred and contempt for other families. But no less unreasonable would it be to take love of country to justify idolatry of country or hatred and contempt for other countries. The monstrous example of Nazi Germany has hammered home to modern people the evil of this excess.

Here is how the manuals just quoted describe the opposite extreme vice:

The virtue is violated by defect by those who boast that their attitude is cosmopolitan and adopt as their motto the old pagan saying: ubi bene, ibi patria (Prümmer, Handbook of Moral Theology, p. 211)

Disrespect for one’s country is felt when one is imbued with anti-nationalistic doctrines (e.g., the principles of Internationalism which hold that loyalty is due to a class, namely, the workers of the world or a capitalistic group, and that country should be sacrificed to selfish interests; the principle of Humanitarianism, which holds that patriotism is incompatible with love of the race; the principle of Egoism which holds that the individual has no obligations to society); it is practiced when one speaks contemptuously about country, disregards its good name or prestige, subordinates its rightful pre-eminence to a class, section, party, personal ambition, or greed, etc. (McHugh and Callan, Moral Theology, Volume II, p. 414)

Here too, the nature and unreasonableness of the vice are best understood on analogy with the case of parents and family. Suppose someone had no special regard for or loyalty toward his own parents or family, on the grounds that we should be charitable and just to everyone and that we shouldn’t regard any family with contempt. This would obviously be a perverse non sequitur. That we have obligations of justice and charity to all people and shouldn’t regard other families with contempt simply does not entail that we don’t have special obligations to our own parents and family or that we don’t owe them a special love and loyalty. In the same way, it is perverse to infer, from the premise that jingoism is wrong, the conclusion that patriotism is wrong too. Avoiding the one extreme does not justify going to the other extreme.

Accordingly, though the kind of cosmopolitanism that puts loyalty to the international community over national loyalty is often regarded these days as morally superior to patriotism, in fact it is immoral, in a way that is analogous to the immorality of refusing to have a special love and loyalty for one’s own parents and family. Similarly immoral are views which replace patriotism with loyalty to one’s economic class (as Marxism does), or one’s race (as both left-wing and right-wing brands of racism do), or one’s narrow economic interests (as global corporations do), or oneself as a sovereign individual owing nothing to any social order at all (as anarcho-libertarianism does).