Edward Feser's Blog, page 42

January 9, 2020

The rationalist/empiricist false choice

I’ve often argued that contemporary philosophers too often think only within the box of alternative positions inherited from their early modern forebears, neglecting or even being ignorant of the very different ways that pre-modern philosophers would carve up the conceptual territory. One of the chief ways this is so has to do with the rationalist/empiricist dichotomy, as filtered through Kant. It has hobbled clear thinking not only about epistemology, but also about metaphysics. The standard Scholastic position, following Aristotle, was that (a) there is a sharp difference between the intellect on the one hand and the senses and imagination on the other, but that nevertheless (b) nothing gets into the intellect except through the senses. To have a concept like triangularityis not the same thing as having any sort of mental image (visual, auditory, or whatever), since concepts have a universality that images lack, possess a determinate or unambiguous content that images cannot have, and so forth. Still, the intellect forms concepts only by abstracting from images, and these have their origin in the senses.

I’ve often argued that contemporary philosophers too often think only within the box of alternative positions inherited from their early modern forebears, neglecting or even being ignorant of the very different ways that pre-modern philosophers would carve up the conceptual territory. One of the chief ways this is so has to do with the rationalist/empiricist dichotomy, as filtered through Kant. It has hobbled clear thinking not only about epistemology, but also about metaphysics. The standard Scholastic position, following Aristotle, was that (a) there is a sharp difference between the intellect on the one hand and the senses and imagination on the other, but that nevertheless (b) nothing gets into the intellect except through the senses. To have a concept like triangularityis not the same thing as having any sort of mental image (visual, auditory, or whatever), since concepts have a universality that images lack, possess a determinate or unambiguous content that images cannot have, and so forth. Still, the intellect forms concepts only by abstracting from images, and these have their origin in the senses.Now, the early modern rationalists and empiricists essentially each embraced half of this position while rejecting the other half. In particular, the rationalists kept thesis (a) while chucking out thesis (b), and the empiricists kept (b) while throwing out (a). For the rationalists, concepts are irreducible to mental images and the intellect is therefore distinct from the imagination and senses. But in that case, they inferred, concepts must be innate rather than grounded in experience. For the empiricists, by contrast, concepts must all be derived from the senses. But in that case, they concluded, concepts must not be distinct from the mental images that are faint copies of sensations, and the intellect essentially collapses into the imagination.

Severing (a) from (b), in these different ways, was the epistemological original sin of the early modern philosophers. (The metaphysicaloriginal sin was the rejection of an Aristotelian philosophy of nature in favor of a mechanical one. The history of modern philosophy is primarily a history of the working out of the implications of these two anti-Scholastic revolutions.)

Against the rationalists, the empiricists would fling the charge that it is an illusion to suppose that you can read off conclusions about mind-independent reality from concepts that have no foundation in the senses, and that it is no surprise that the rationalists ended up constructing metaphysical systems that were ever more bizarre and untethered from reality. Against the empiricists, the rationalists would object that you cannot arrive at truly universal concepts and general propositions from mere images, and that it is no surprise that empiricism led to ever more radical skepticism about the external world, causality, the self, etc., and shrank the realm of the knowable to the immediate contents of consciousness (if that). Both of these lines of criticism are correct. The error is in thinking that accepting the criticisms of one of these two views requires adopting the other, as if there were no third position.

Kant might seem to have provided a third position, but it would be closer to the truth to say that he embraced both errors at once. He essentially agrees with the rationalists that the fundamental categories by which we carve up reality cannot come from experience and must be innate, but also agrees with the empiricists that these categories so understood will never afford knowledge of mind-independent reality. Hence he concludes that these categories tell us only about how we have to thinkabout mind-independent reality, not how it really is in itself. It is no surprise that the sequel to Kant was 19th century idealism, which was as metaphysically extravagant as the empiricists would accuse the rationalists of being, and as prone to collapsing all reality into the mental as the rationalists would accuse the empiricists of doing.

Contemporary philosophy tends to bounce around this rationalist/empiricist/Kantian box rather than try to find a way out of it. I say only that it tends to do so, because of course there are, as I have also often noted, many neo-Aristotelian developments in contemporary philosophy that amount precisely to efforts to get outside the box. But the responses to such developments often reflect an inability to see outside it.

Hence, consider the view, common among analytic philosophers, that the only sorts of truths there are are either those of natural science or those of conceptual analysis, so that philosophy must be oriented toward one or the other. Philosophers who think of their discipline as primarily devoted to conceptual analysis tend to fall either into a kind of rationalism or a kind of Kantianism, with predictable results. If they claim, as a rationalist would, that what they say about essences, causality, possible worlds, etc. reflects something about objective reality, their critics will say: How can mere conceptual analysis yield such momentous results? Why should reality conform to our concepts? If instead they say, a la Kant, that the results of conceptual analysis tell us only how we must think about reality, the critics will say: So what? Maybe we’re thinking about it the wrong way, and in particular in ways that reflect merely how natural selection or our cultural circumstances shaped our minds, rather than the way things really are.

Those who hold instead that philosophy is an extension of natural science tend to fall into a kind of empiricism, or into a kind of Kantianism proceeding from the empiricist rather than rationalist direction. Their critics will say: Natural science has to be interpreted in either an instrumentalist or a realist way. If we read it the first way, then it doesn’t get us knowledge of the objective world, and we’re stuck with a riff on Humeanism. That’s essentially what logical positivism was, and it and other forms of antirealism are problematic in the usual well-known ways. If instead we read science in a realist way, then we are taking on board a substantive metaphysics. But then the history of scientific revolutions and Kuhnian points about the social nature of science raise questions about how objective such a metaphysics can be. Maybe it gives us knowledge only of how the scientific community conceptualizesreality rather than how it really is – which is essentially a riff on Kantianism.

Interestingly, if you’re someone working in analytic metaphysics who thinks that we canget a more robust metaphysics than the critics of conceptual analysis suppose, or if you’re someone working in philosophy of science who think that natural science does give us something in the way of old-fashioned metaphysics, there is a good chance that you are a neo-Aristotelian who has made your way out of the box the early moderns put us in. (I have in mind people like Molnar, Martin, Mumford, et al. in the first case, and Cartwright, Ellis, Bhaskar, et al. in the second.)

Anyway, the conceptual analysis/natural science dichotomy is essentially a riff on the logical positivists’ dichotomy between analytic propositions and empirically verifiable propositions, which was in turn a riff on Hume’s dichotomy between relations of ideas and matters of fact (“Hume’s Fork”). And it is no more defensible than those ancestors are. (See pp. 139-51 of Aristotle’s Revenge for detailed discussion.)

Other echoes of the rationalist/empiricist false dichotomy arise in discussions of arguments for God’s existence and for the immateriality of the mind. For the ancients and medievals, First Cause arguments can get us from premises about the empirical world, by way of strictly demonstrative reasoning, to a conclusion about an absolutely necessary cause outside the world. I’ve defended such arguments myself. But if you’re a Humean, no such argument is possible. If you’re starting from the empirical world, you can only ever get probabilistic conclusions and you can’t conclude to anything that exists of metaphysical necessity. The most you might be able to construct by way of an empirically-based natural theology is a Paley-style inductive argument that gets you at best to a kind of demiurge rather than to the God of classical theism. On the other hand, if you are going to provide a strict demonstration of a truly necessary being, then you are going to have to reason a priori. But that only gives you at most knowledge of the relations between concepts, rather than of objective reality. This is the inspiration for Kant’s influential view that the cosmological argument ultimately depends on the ontological argument, and therefore fails given that the latter argument does. Contemporary criticisms of First Cause arguments to the effect that they are dubious scientific hypotheses, or that all necessity is merely the logical necessity that holds of the relation between concepts but tells us nothing about objective reality, reflect this broadly Humean way of carving up the conceptual territory.

Meanwhile, arguments for the immateriality of the mind like Richard Swinburne’s or W. D. Hart’s, which appeal to conceivability or to possible worlds, are essentially rationalist in spirit, and problematic for the reasons that rationalism in general is. And it seems to be commonly supposed that if an argument for immateriality isn’t of this sort, then the only other thing it could be is a kind of quasi-scientific inductive hypothesis. But arguments for the immateriality of the intellect of the kind Thomists would give fall into neither of these categories.

For example, consider the argument for immateriality from the determinate or unambiguous nature of the contents of our thoughts, which I have defended. This argument does not start with some claim about what is conceivable or about possible worlds, and then try to deduce from that the immaterial essence of the intellect. That sort of procedure gets things backwards. We have to know the essence of a thing first, before we can know what is conceivable with respect to it, or what might be true of it in various possible worlds. But neither is the argument a mere probabilistic hypothesis. It begins with experience in the sense that it starts with what we know about our own thoughts and their conceptual content just by virtue of having them. But it proceeds from that starting point to try to give a strict demonstration that thought cannot be material.

Properly to understand the arguments of Aristotelians, Thomists, Neo-Platonists, and other thinkers in the classical or pre-modern tradition requires being careful not to read them as if they were variations on some broadly rationalist, empiricist, or Kantian theme. The roots of the arguments historically predate, and are conceptually distinct from, these modern tendencies.

Published on January 09, 2020 15:04

January 3, 2020

Links for a new year

Joseph Bessette on criminal sentencing laws and retributive justice, at Public Discourse.

Joseph Bessette on criminal sentencing laws and retributive justice, at Public Discourse.The Catholic Thing on the late, great Michael Uhlmann . Requiescat in pace, Mike.

At The New Atlantis, Benjamin Liebeskind reviews Neo-Aristotelian Perspectives on Contemporary Science .

At The Spectator, Roger Scruton looks back with gratitude at an annus horribilis.

Jez Rowden’s Steely Dan: Every Album, Every Song will be released next month. Ultimate Classic Rock on the great Eagles/Steely Dan cross-reference. What Is It Like to Be a Philosopher? interviews Scott Soames . Soames’s new book The World Philosophy Made has just been released.

Sabine Hossenfelder of BackReaction on the crisis in physics , mathematical laws of nature , and cognitive bias in science .

Richard Marshall interviews philosopher Thomas Pink , at 3:16.

Glenda Satne reviews Alex Rosenberg’s How History Gets Things Wrong , at Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews. Bookforum on flummery in the name of neuroscience .

Sexual immorality and the decline of civilizations: Kirk Durston on J. D. Unwin’s Sex and Culture.

Forbes on the final season of The Man in the High Castle. The Wrap explains that enigmatic ending.

J. K. Rowling, Ricky Gervais, and the right to say the obvious. Theodore Dalrymple comments at City Journal, and Kyle Smith provides an update at National Review. Spikedwonders whether the tide is starting to turn against trans lunacy.

Regulating pornography: Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry on why it should be done, at American Greatness. Terry Schilling on how it can be done, at First Things. Gerard Bradley on the same theme, at Public Discourse.

Capturing Christianity interviews philosopher Tim Hsiao on the topic of sexual morality.

Massimo Pigliucci reviews Paul Feyerabend’s Philosophy of Nature, at Philosophy Now.

At Harper’s, Lionel Shriver on left-wing linguistic legerdemain. Los Angeles Review of Books on David Bromwich on the left and free speech.

Church Times reports on Rupert Shortt’s new book Outgrowing Dawkins: God for Grown-Ups . Ben Sixsmith at Arc Digital performs an autopsy on the New Atheism. Prospect on agnostic Stephen Asma on our need for religion.

Also at 3:16, Richard Marshall interviews philosopher of biology John Dupré.

At Science, James Gunn on Isaac Asimov at 100. Asimov’s Foundationseries is being adapted for television by Apple. When science fiction gets things wrong, at The New Republic.

Times Literary Supplement reviewsJohn Gribbin’s and Lee Smolin’s new books on quantum mechanics. IAI TVinterviews philosopher of physics Tim Maudlin about the same subject.

There is a website devoted to the work of Australian Thomist Austin Woodbury.

At Church Life Journal, Shaun Blanchard on the smear word “Jansenist,” and Richard Yoder on a pope who was resisted.

At Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews, Darrell Rowbottom reviews K. Brad Wray’s Resisting Scientific Realism.

Fr. Mitch Pacwa interviews philosopher Jennifer Frey on EWTN Live.

James Franklin on Aquinas’s realism for The Sydney Realist.

Published on January 03, 2020 18:56

December 28, 2019

Overestimating human responsibility

One of the many pernicious aspects of modern political life is the tendency, every time something bad happens, to look for someone to blame – or, where someone is to blame, to try to extend the blame to people who can’t reasonably be held responsible. “It’s the Republicans’ fault!” “It’s the Democrats’ fault!” “It’s the NRA’s fault!” “It’s the environmentalists’ fault!” “It’s the government’s fault!” “It’s the corporations’ fault!” “We need new legislation!” “We need an investigation!” Naturally, sometimes those things are true. But sometimes they’re not. Sometimes it’s no one’s fault. Sometimes nothing is to be done. Sometimes no new legislation is needed, and enforcement of existing legislation is already as good as can reasonably be expected. The reason is that human action and legislation obviously cannot possibly stop every bad thing from occurring. Sometimes “shit happens” and that’s that.

One of the many pernicious aspects of modern political life is the tendency, every time something bad happens, to look for someone to blame – or, where someone is to blame, to try to extend the blame to people who can’t reasonably be held responsible. “It’s the Republicans’ fault!” “It’s the Democrats’ fault!” “It’s the NRA’s fault!” “It’s the environmentalists’ fault!” “It’s the government’s fault!” “It’s the corporations’ fault!” “We need new legislation!” “We need an investigation!” Naturally, sometimes those things are true. But sometimes they’re not. Sometimes it’s no one’s fault. Sometimes nothing is to be done. Sometimes no new legislation is needed, and enforcement of existing legislation is already as good as can reasonably be expected. The reason is that human action and legislation obviously cannot possibly stop every bad thing from occurring. Sometimes “shit happens” and that’s that.Commenting on the characterization of conservatism as a “politics of imperfection” in his book A Case for Conservatism , John Kekes writes:

[One] respect in which the politics of imperfection is a misleading label is its suggestion that the imperfection is in human beings. Now conservatives certainly think that human beings are responsible for much evil, but to think only that is shallow. The prevalence of evil reflects not just a human propensity for evil, but also a contingency that influences what propensities human beings have and develop, and thus influences human affairs independently of human intentions. The human propensity for evil is itself a manifestation of this deeper and more pervasive contingency, which operates through genetic inheritance, environmental factors, the confluence of events that places people at certain places at certain times, the crimes, accidents, pieces of fortune and misfortune that happen or do not happen to them, the historical period, society, and family into which they are born, and so forth. The same contingency also affects people because others, whom they love and depend on, and with whom their lives are intertwined in other ways, are as subject to it as they are themselves…

[W]hether the balance of good and evil propensities and their realization in people tilts one way or another is a contingent matter over which human beings and the political arrangements they make have insufficient control… The chief reason for this is that the human efforts to control contingency are themselves subject to the very contingency they aim to control. (pp. 42-43)

That last line is crucial. The problem is a problem in principle and not one that can be legislated away or solved technologically, because such remedies, being subject to the same pitfalls that are being remedied, can only ever kick the problem back a stage.

The braindead response to this is to dismiss it as a cynical rationalization for complacency and inaction. The problem Kekes describes is either real or it is not. If it is not, then the right way to answer the conservative is to show where Kekes’s argument goes wrong, not to question conservative motives. And if the problem is real (as, of course, it obviously is) then questioning conservative motives doesn’t somehow make it less real.

Someone might respond by saying that even though it is true that we cannot solve every problem through legislation or technology, it is still better to act as if we can. For that way we can at least make things better, even if not perfect, and we will not overlook potential solutions that we are bound to miss if we give up too soon and don’t even bother looking for them.

But the problem with this attitude is that it forgets that vices come in pairs. If there is danger in giving up too soon, there is also danger in going to the opposite extreme of a stubbornly naïve optimism that cannot see that a cause is hopeless and that it’s better to cut one’s losses. An insistence on searching for solutions where there are none is a recipe for wasting time, resources, and emotional energy. It is also bound to exacerbate the demagoguery and factionalism to which democratic politics is already prone. A politician who promises a phony legislative solution to a problem has an obvious advantage over one who frankly acknowledges that the problem can only be managed rather than solved. He also has an incentive to demonize those who oppose his pseudo-solution as the selfish and irrational enemies of progress.

Democratic politics is indeed one of the chief sources of the illusion that for every problem, someone is to blame. There is simply too great a political advantage to be gained in finding a way to blame one’s opponents for a problem, or at least for standing in the way of a purported legislative solution, for this illusion not to take deep root in a democratic polity. And of course, conservative politicians too can be guilty of fostering this illusion, precisely because they are politicians.

Secularism can be another source of the illusion. It is easier to accept the fact that some problems are simply part of the human condition, and thus cannot be blamed on anyone, when your heart isn’t set on this life in the first place, but instead looks forward to an afterlife. By contrast, if you think that this life is all there is, then the fact that some of its miseries cannot be remedied can be a source of despair. It will be tempting to want to believe that there is always a solution, and consequently a tendency to demonize those who deny that there is.

However, it would be foolish to suppose that secularism mustlead to this outcome, or that religion cannot in its own way sometimes foster the illusion that someone is always to blame. Indeed, some irreligious people might be less prone to the illusion. If you think that there is no benevolent creator and no divine providence, you might be morerather than less inclined to think that much of the evil that occurs is simply the inevitable result of forces outside of anyone’s control. (It is worth noting in this connection that Kekes himself, though conservative, is not religious.)

Religious people can also be inclined to overestimate human responsibility for evil, as a consequence of having too crude an understanding of the doctrine of original sin. Elsewhere I’ve discussed what I think is the correct way to understand the doctrine. The penalty of original sin is essentially a privation rather than a positive harm, and in particular a privation of supernatural goods – that is to say, goods which go beyond our nature, goods to which our nature does not incline or entitle us, but which God would have granted us anyway had our first parents not failed to meet the conditions for their reception. Specifically, these goods are the beatific vision, and special divine assistance to remedy the limitations of our nature.

The latter is the one most relevant to the topic of this post. Human nature of itself is good, but it is severely limited. For example, given our dependence on bodies, we are severely limited in knowledge. We have to learn things through sense organs, and what we learn is highly contingent on exactly where we happen to be in space and time and on what people we encounter. It also requires not only that our sense organs function properly, but that our brains do as well (since brain activity is a necessary condition for the normal functioning of our cognitive processes, even if it is not, for the Thomist, a sufficient condition). If we are in the wrong place at the wrong time or know the wrong people, or if our faculties malfunction, we are bound to fall into error, and these errors will compound over time as other errors are added to them, mistaken inferences are drawn, etc. And this would be true even apart from any sins we might commit. It is simply a byproduct our limitations.

But we would be bound to fall into sin too. Material systems, being material, are bound over time to malfunction in various ways, and the human body is no different from any other in this regard. Not only will our cognitive faculties fail to function properly from time to time, but so too would our affective faculties. We would be prone to occasional excess or deficiency in anger, sexual desire, hunger, thirst, and so on, and this would make it easier for us to choose from time to time to do the wrong thing.

Naturally, we would also be subject to various harms from without – to disease, bodily injury, predation from other creatures, the lack of resources with which to provide food or shelter for ourselves, and so on. Now, all of this would have been remedied by special divine assistance had our first parents not failed their test. Our cognitive faculties would have been supplemented so that their limitations would not lead us into error. The potential causes of excess and deficiency in our affective states would have been counteracted so that these disordered passions would not arise and tempt us to sin. There would have been no absence of the resources needed to feed, clothe, and shelter ourselves, our bodies would have been protected from invasion by parasites or predation by other animals, and so on.

The penalty of original sin involves the loss of all of this special assistance, and that is crucial for understanding what it means to say that human suffering is the result of original sin. Some people seem to think that what that means is that every bad thing that happens to us is somehow positively caused by what our first parents did (like a kind of karmic penalty), or that it is the direct infliction on us of some harm (by God as punishment, or by demons), or that human beings have as a result of the Fall all become somehow sociopathic deep down, our every action the product of some wicked motive in disguise. In short, there is a tendency to think that original sin entails some malign agency behind every bad thing that happens, and some malignity to all human agency.

But that is a misunderstanding. When a person slips and falls off a cliff or contracts a disease or loses all his money in the stock market, the doctrine of original sin does not entail that those specific harms were merited as punishment (by him or by our first parents), or that a demonic agency is responsible for them, or that they were somehow the inevitable end of a karmic causal chain that began with Adam and Eve. All it entails is that misfortunes of this sort, some of which happen as nature takes its course and without anyone making them happen, would have been prevented had our first parents not lost the special divine help they were offered.

The doctrine also does not entail that there is no goodness of any kind in anything anyone does – for example, that even a mother who breastfeeds a child or a father playing catch with his son are somehow really deep down moved to do these things by some purely selfish and evil motive, rather than by natural affection or kindness. When one supposes that the doctrine of original sin does entail this, it can lead to an excessive suspicion of all human motives. Human action can come to seem so malign that is easier to fall into the trap of thinking that when something bad happens, someone somewhere is to blame, or that those who oppose some proposed remedy must have evil motivations.

Published on December 28, 2019 12:36

December 20, 2019

Cundy on relativity and the A-theory of time

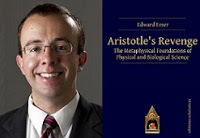

One of the many topics treated in

Aristotle’s Revenge

is the relationship between Aristotelian philosophy of nature and contemporary debates in the philosophy of time. For example, I argue that, while at least the most fundamental claims of an Aristotelian philosophy of nature might be reconciled with the B-theory of time, the most natural position for an Aristotelian to take is an A-theory, and presentism in particular. Thus was I led to defend presentism in the book – which requires, among other things, arguing that the presentist view of time has not been refuted by relativity theory. Nigel Cundy disagrees. A physicist with a serious interest in and knowledge of Aristotelian-Thomistic philosophy, he has posted a detailed and thoughtful critique of this part of my book at his blog The Quantum Thomist. Cundy thinks that presentism cannot be reconciled with relativity, and that other A-theories of time at least sit badly with it. What follows is a response. Cundy’s article is very long, but it has to be in order to set out the case Cundy wants to make. It is well worth reading and you may want to take a look at it before proceeding, so that you have the entire context. There are six main parts of his article. The first is an introduction, and in the second he sets out the physics of space and time. In the third, he evaluates the A-theory and B-theory in light of the physics. In the fourth, fifth, and sixth sections, Cundy addresses my criticisms of the B-theory, my treatment of relativity, and my defense the A-theory. I’ll comment on each of these parts in turn.

One of the many topics treated in

Aristotle’s Revenge

is the relationship between Aristotelian philosophy of nature and contemporary debates in the philosophy of time. For example, I argue that, while at least the most fundamental claims of an Aristotelian philosophy of nature might be reconciled with the B-theory of time, the most natural position for an Aristotelian to take is an A-theory, and presentism in particular. Thus was I led to defend presentism in the book – which requires, among other things, arguing that the presentist view of time has not been refuted by relativity theory. Nigel Cundy disagrees. A physicist with a serious interest in and knowledge of Aristotelian-Thomistic philosophy, he has posted a detailed and thoughtful critique of this part of my book at his blog The Quantum Thomist. Cundy thinks that presentism cannot be reconciled with relativity, and that other A-theories of time at least sit badly with it. What follows is a response. Cundy’s article is very long, but it has to be in order to set out the case Cundy wants to make. It is well worth reading and you may want to take a look at it before proceeding, so that you have the entire context. There are six main parts of his article. The first is an introduction, and in the second he sets out the physics of space and time. In the third, he evaluates the A-theory and B-theory in light of the physics. In the fourth, fifth, and sixth sections, Cundy addresses my criticisms of the B-theory, my treatment of relativity, and my defense the A-theory. I’ll comment on each of these parts in turn.The physics of space and time

Cundy’s second section puts forward an admirably lucid exposition of the methodology and content of modern physics’ account of space and time. One of the themes I consistently hammer on in Aristotle’s Revenge is the highly abstract character of physics’ description of nature, and Cundy’s exposition beautifully conveys that. I want to pull out several key passages from his discussion, because they are essential to understanding Cundy’s main points and the points I will make in response. Cundy writes:

We perform a mapping to a geometrical space, which is an abstract object. So every point in physical space time corresponds to a point on the geometrical space, and vice versa. We have a great deal of freedom in choosing the geometrical abstraction, but not total freedom… We then perform a second mapping from the geometrical space time to a coordinate space, i.e. we assign a number to every point in the geometrical space. Again, this is a one to one mapping, and there is even more (but not total) freedom in how we do this… This freedom should not affect our predictions concerning physical space time. Wherever we place the origin of our coordinate system, we should make equivalent predictions. There are not many possible theories which pass this criteria, and one of the driving forces behind contemporary physics is that we are restricted to just those theories. Indeed, this is one of the key principles behind the theory of relativity.

End quote. This is followed by a description of how this approach to representing space and time gets worked out in the case of special relativity. Cundy then writes:

This geometry provides a background on which physics takes place. It is not all there is to physics. Additionally, we require an additional set of abstract objects which represent the matter (or perhaps our knowledge of material states). This second abstraction builds upon the representation of space time, since we say that there is a certain likelihood (or amplitude) that a particular particle exists at a particular place, and the representation of matter thus depends on the coordinate system being used. When we perform a coordinate transformation, we must also at the same time transform the details of how we represent a material object. So the representation of matter is linked to the representation of space time, but contains additional information.

We can also introduce natural coordinate systems for each observer, i.e. where the observer is at the origin of their coordinate system… So two observers A and B each have their own coordinate system with themselves at the origin.

End quote. Now, a representation is abstract to the extent that it focuses on certain features of the thing represented to the exclusion of others, and the specific mode of abstract representation utilized by modern physics is mathematical. What Cundy is pointing out so far is that space, time, matter, and the observer are represented in special relativity in a way that is doubly abstract. It isn’t just that they are represented geometrically, but that the geometry in turn is represented in an abstract coordinate system. Cundy continues:

The statement of relativity is that coordinate systems must be relative to each other, and that there is no absolute coordinate system. This I take to be so deeply enshrined in physics that I don't think that anybody can rationally challenge it. It also makes philosophical sense: there is no right way in which to construct the abstraction. We have to pick one, but ultimately we are free to choose. "Absolute space" is interpreted to mean that there is some preferred frame of reference, and with regards to describing the locations and times of physical objects this is not the case.

End quote. Cundy then moves on to a discussion of symmetry. But before we turn to that we need to pause, because it seems to me that Cundy is inadvertently gliding over a crucial issue here. Let’s concede for the sake of argument that the relativity of coordinate systems is indeed “so deeply enshrined in physics that I don't think that anybody can rationally challenge it.” Whyis it so deeply enshrined?

As philosophers of science sometimes point out, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that the reason has to do with the verificationismthat famously guided Einstein as he first hammered out special relativity, and that was so influential in physics and philosophy at the time. The sense in which there is no preferred frame of reference is simply that there is no empirical test that can justify a preference for one frame rather than another.

Now, the problem this poses is this. Verificationism can be read either as a philosophical position or as a methodological constraint. As a philosophical position, it is the thesis that no statement is meaningful unless it is either analytic or empirically testable (where mathematics is put on the analytic side of this divide). In the present context, this would have the implication that talk of an absolute frame of reference is, since neither analytic nor empirically testable, strictly meaningless. That is to say, it literally has no intelligible content. Special relativity coupled with philosophical verificationism would thus have the dramatic metaphysical consequence that it is in principle impossible for there to be a privileged reference frame. The trouble with this interpretation, though, is that verificationism has been refuted about as decisively as a philosophical thesis can be. The problems with it (which I summarize at pp. 139-45 of Aristotle’s Revenge) are many and grave, and they led to its almost complete abandonment within philosophy of science by the middle of the twentieth century.

Better, then, to read verificationism as a mere methodological constraint. Here the idea would be that even if statements that are neither analytic nor empirically testable are not strictly meaningless, physics is simply not concerned with them. Physics, on this view, ought to confine itself to what is susceptible of what Jacques Maritain called an “empiriometric” analysis, viz. the use of mathematical representations to organize data about what is directly empirically detectable. While there may or may not be aspects of reality that are beyond empirical testing and/or mathematical representation, they are simply not within the ambit of physics.

Now, whereas verificationism as a philosophical thesis has radical metaphysical implications, verificationism as a methodological constraint has, by itself, no metaphysical implications at all. Hence the absence of an absolute reference frame from special relativity, when interpreted in light of merely methodological verificationism, by itself does not entail that there is no absolute reference frame in objective reality. The failure of a method to reveal some thing X gives you reason to think that X does not exist only if you already have independent grounds for thinking that the method would have revealed X if X did exist. In the present case, the absence of a privileged reference frame from the physics of relativity would entail that there is no such frame in objective reality only if we have an independent philosophical rationale for thinking that the physics would reveal it if it were there. And in that case it would really be the philosophical rationale, and not the physics, that is doing the main work.

The trouble is this. This distinction between philosophical implications and merely methodological constraints is, it seems to me, constantly blurred in discussions of the metaphysical implications of relativity. Rightly impressed by the inherent beauty and brilliance of Einstein’s theory and by its spectacular empirical successes, people jump to the conclusion that the physics of relativity has established some dramatic metaphysical claim – that presentism is false, that time is an illusion, or what have you. But the physics has done no such thing. It would have such implications only given philosophical verificationism, or given some other philosophical argument in defense of the thesis that the methodology of physics provides an exhaustive description of its subject matter. And in that case it would, again, be the philosophical arguments, and not the physics, that are doing the metaphysical heavy lifting. You won’t ever pull more philosophy out of physics than you first put in.

Since Cundy’s view seems to be that relativity of itself rules out presentism and threatens other versions of the A-theory as well, this should raise a red flag. But Cundy has a lot more to say, so let’s return to his exposition. He turns next to an explanation of symmetry, and he relates this to the notion of structural realism. He writes:

Professor Feser himself adopts structural realism, where the reason that the abstract representation used by physics is successful is that it maintains the same relationships between the representations of the objects as exists in reality. I quite agree with him that this is crucial…

Now identifying a symmetry relies on two principles, the transformation or relationship between different points (or potentia in things), and the statement that two physical configurations are equivalent. As a structural realist, Professor Feser would agree that there must be something corresponding to the transformation in physical reality if the physical description is accurate. Equally, if two configurations are equivalent in reality, if it is to be in any way accurate, they must also be so regarded in the abstracted representation (and if they are not equivalent, they must be distinct in the representation). Thus if we need to construct the representation with a particular symmetry in order to make it line up with reality, then that symmetry must also be present in reality. So if you give the idea of structural realism to a contemporary physicist, part of what he will do to break it down into something he can work with is to demand that both reality and the physical abstraction should respect the same symmetries.

End quote. Now, here we need to pause again. The kind of structural realism I defend in Aristotle’s Revenge is, specifically, epistemic structural realism. This is a middle ground position between instrumentalism on the one hand, and scientific realism of the usual sort on the other. It holds, against instrumentalism, that physics is not merely a useful tool for making predictions and developing technologies, but really does reveal to us something that is objectively there in nature. But it also holds, against the more familiar sort of scientific realism, that what this something is is merely the mathematical structure of the natural world. In particular, physics reveals mathematical relations, but does not tell us about the intrinsic nature of the entities related by these relations. (Or to be more precise, we can have much less confidence in anything physicists have to say about the relata themselves than we can have that the mathematical relations that relate them are real.)

Cundy is astute to emphasize this view of mine, because it is an absolutely crucial component of the overall argument of Aristotle’s Revenge. Some readers seem to jump straight to whatever part of my book deals with some particular topic they are especially interested in, and to read that part in isolation from the rest of the book. This can lead to serious misunderstandings. Epistemic structural realism is not some incidental part of the book. It is central to the way I deal with a number of topics, especially topics in physics.

Cundy not only does not make the mistake of overlooking this, he cleverly tries to use this broader philosophical commitment of mine as a way to force me into precisely the sort of interpretation of relativity that I am using structural realism to avoid. (Though as an aside – and to forestall a foolish ad hominemobjection I am sure some hostile reader will try to raise – I do not adopt structural realism for the purpose of avoiding such an interpretation of relativity, in an ad hoc way. As the book shows, I have ample independent grounds for adopting structural realism. Indeed, I’ve been a structural realist since before I was a Thomist, way back in my atheist days in the 1990s when I first got interested in the work of the later Bertrand Russell. It is a standard option in philosophy of science that is typically defended for reasons having nothing to do with debates over presentism, Aristotelianism, etc.)

Cundy’s strategy is going to be to argue that even if what physics reveals is structure, if symmetries in the mathematical representation of nature mirror symmetries in nature itself, then we should conclude that there must be in nature something corresponding to the structure represented in the physics of relativity. And since the latter treats past and future events as on a par with present ones, we should conclude that past and future events really are no less real than present ones – which is, of course, precisely what presentism denies.

As I say, this is a smart strategy, but I don’t think it works. The reason is that the structure affirmed by the usual formulations of structural realism (including mine) is much more abstract than Cundy’s argument requires. Take, for starters, Russell’s version of structural realism. As I discuss in the book, Russell’s initial version of the view held that what physics reveals to us is in fact only the properties of the relations holding between the entities to which it refers, as captured in the language of modern formal logic. This is extremely abstract – it tells us only that the entities to which physics refers bear relations to one another that have properties such as transitivity, reflexivity, and the like. It opened Russell up to an objection raised by the mathematician M. H. A. Newman, according to which Russell’s position made the knowledge afforded by physics entirely trivial.

Now, a structural realist need not take Russell’s approach, and in Aristotle’s Revenge I reject it. The point is just that there are various things “structure” can mean, and the more abstract one’s conception of the structure revealed by physics is, the less metaphysical bite physics can have. Now, the version of structural realism I defend in the book is closer to that of the contemporary philosopher of science John Worrall. Worrall’s view is that what tends to be preserved through theoretical revolutions in physics are mathematical equations. A favorite example of his is the equations that survived the transition from Fresnel’s account of the nature of light to Maxwell’s account. Now, though they use the same equations, Fresnel thought of light in terms of an elastic solid ether, whereas Maxwell thought of it in terms of a disembodied electromagnetic field. That illustrates just how metaphysically thin the knowledge of objective reality provided by the equations is. The truth of the equations does not by itself tell in favor of one or the other of these very different conceptions of the nature of light. Only considerations distinct from the equations can do so.

In the case of special relativity too, the mathematics is compatible with a variety of possible metaphysical interpretations. One could, of course, adopt a B-theory of time. But as William Lane Craig emphasizes, one could instead accept the mathematics and nevertheless adopt Lorentz’s conception of space and time rather than Einstein’s. Or one could take Dean Zimmerman’s view that there is a privileged slicing of the four-dimensional spacetime manifold that corresponds to the present, but that physics is simply unable by its methods to identify it and must be supplemented by metaphysics. Or one could endorse Michael Tooley’s attempt to marry special relativity to a “growing block” version of the A-theory. Or one could take yet some other option. (I discuss all these in the book.)

It is crucial to understand exactly what I am saying here. I am notendorsing Craig’s neo-Lorentzian position, or Zimmerman’s or Tooley’s or any other interpretation. That’s not the point. The point is that the mathematics by itself (which, for the structural realist, is all that the physics gives us confidence in) doesn’t tell you which of these views, with their radically different metaphysical implications, is correct. Mathematical structure is simply too abstract for that. Hence physics interpreted in a structural realist way is not going to have the metaphysical bite that Cundy seems to think it does. And so it cannot refute presentism or the A-theory more generally or any other metaphysical position regarding time. There may or may not be other reasons that decisively refute one or more of these positions, but if so they will have to be reasons additional to the mathematical representation.

Coming back to Cundy’s exposition, let us now consider what he says about the relationship between space and time. He writes:

Would the symmetry then just map points next to each other in time, and not require the whole four dimensional space? But if we say that the symmetry only maps the neighbouring points of time means that only those neighbouring points exist, then we ought to conclude the same thing about space. Nobody denies the existence of points far from me when considering a space-space rotation. We should conclude the same thing when considering a rotation between space and time.

End quote. Cundy’s argument here appears to be that since relativity treats past and future points in time in a way that is analogous to the way it treats distant points in space, to be consistent we should regard them as ontologically on a par. In particular, since we regard distant points in space as no less real than near ones, we should regard past and future points in time as no less real than the present one.

Naturally, this invites the retort that Cundy is fallaciously reading into physical reality features that reflect only the mode of representation rather than reality itself – in particular, that he is supposing that since the mathematics effectively spatializes time, time itself must be something like a spatial dimension. But Cundy has a reply to this objection. Alluding to some points he had made earlier in his exposition, he writes:

Just because we are treating space and time as contained within one four dimensional block does not mean that time is just the same sort of thing as space. I want to highlight three differences. Two I have already mentioned. The first is that minus sign in the metric; that is of significant importance. The second is the need for time ordering in the calculation of the amplitude: this is an admission that we cannot ignore the causal sequence. The third is related to energy and momentum. In quantum physics, momentum is a measure of how likely a particle is to move in space, or, on average, how fast it moves. Energy is the corresponding quantity relating to time; it tells us how quickly the particle's internal clock moves... But while momentum can be either positive or negative – particles can move forwards and backwards in space – energy is always positive. This means that particles can only move forwards in time.

The first of these differences is well acknowledged by the philosophers who favour the tenseless theory of time, but the second two, arising from relativistic quantum field theory rather than special relativity alone, are perhaps less well known. Together, they mean that a) there is a direction in time, from past to future, and b) moments of time follow one after another. These differences apply to time but not space.

End quote. Now, in Aristotle’s Revenge I explicitly acknowledge (at pp. 275-76) that modern physics does not in fact treat time exactly as it does space, and certainly it does not assimilate time to the commonsense notion of space. So this is a bit of a red herring. What is really going on, I argued, is that mathematical representations of the sort Cundy has been describing essentially desiccate both time and space. It’s not that they drag time down into the world of concrete spatially located objects, making movement through time literally like forward movement through space. It’s rather that they raise space and time alike up into eternity. They make of space-time a kind of Platonic abstract object that is spaceless no less than it is timeless, or at any rate is like neither time nor space in the ordinary conceptions of those things.

The features identified by Cundy don’t show otherwise. Directionality and succession do not suffice for time, or for space for that matter. Number series exhibit both, but they are neither temporal nor spatial. After 1 comes 2, after that comes 3, then 4, and so on. Numbers get larger as you go forward in the series just as you get older as you go forward in time, and the numbers can’t change places in the series any more than events can. But again, number series are not temporal.

No doubt Cundy will say that it is the causal relations between events in a series that makes them temporal. But the problem is that it is also hard to see what remains of the ordinary notion of causalitywhen the ordinary notions of space and time are both replaced by coordinate systems of the kind Cundy describes. If points in time are as equally real as points in space, then a stick’s going from rest to motion is like it’s being red at one end and green on the other. The latter is not a change but just the having of different attributes at different spatial parts, and it is hard to see how the former amounts to a true change either, as opposed to merely the having of different attributes at different temporal parts. And if we replace our ordinary notion of space no less than our ordinary notion of time with the idea of points in an abstract coordinate system, the result is something even less like change in the ordinary sense. But without change in the ordinary sense (which, Cundy agrees, entails the actualization of potential) what becomes of causalityin the ordinary sense? We don’t seem to be talking about change or causality at all as we consider the coordinate systems Cundy is describing, but simply noting different aspects of a kind of Platonic object.

As the philosopher of physics Lawrence Sklar points out, a persistent source of fallacies when discussing the metaphysical implications of physics is the circumstance that the physicist often uses the same words as common sense does, but attaches to them radically different meanings. This generates the illusion that the physicist and the man on the street are talking about the same thing, when in fact they are not. When the link of analogy between “time” in the ordinary sense and “time” as the physicist uses the term has been broken, the continued use of the same term invites a fallacy of equivocation. Sklar writes:

If what we mean by ‘time’ when we talk of the time order of events of the physical world has nothing to do with the meaning of ‘time’ as meant when we talk about order in time of our experiences, then why call it time at all? Why not give it an absurd name, deliberately chosen to be meaningless (like ‘strangeness’), and so avoid the mistake of thinking that we know what we are talking about when we talk about the time order of events in the world? Instead let us freely admit that all we know about ‘time’ among the physical things is contained in the global theoretical structure in which the ‘t’ parameter of physics appears. And all the understanding we have of that global structure is that when we posit it, it constrains the structure among those things presented to our experience in a number of ways. And that is its full cognitive content. (“Time in experience and in theoretical description of the world,” pp. 226-27)

What Sklar says about “time” is no less true of words like “space,” “change,” and “cause.” Because the physicist continues to use these words, it can seem like he is talking about the same thingsas the man on the street and the Aristotelian metaphysician are when they use those terms. But that is not the case, because the elements of the world that are constitutive of time, space, change, and causality in the ordinary and Aristotelian senses have been drained out of the mathematical representation utilized by the physicist. Hence Cundy seems to me in danger of exactly the sort of equivocation that Sklar is warning of.

The A-theory and B-theory in light of physics

Let’s turn now to the section of Cundy’s article which applies the physics to the dispute between the A- and B-theories of time. Presentism is the version of the A-theory that I favor, but Cundy judges that it is flatly incompatible with the physics of relativity. He writes:

It should be immediately obvious that presentism violates Lorentz symmetry. It requires that only one moment of time, the same moment throughout the universe, is real, and there is a distinction between the past and future on one hand and the present on the other. The geometrical and coordinate representations contain points for all of past present and future. This means that we can map between the present in reality and one time slice in the representation, but there isn't anything to map to the locations in the representation which represent past and future events. This means that the representation would have Lorentz symmetries, mixing time and space, but reality can't… Thus, if presentism were true, the representation would have a greater degree of symmetry than reality. As stated above, this is impossible (if the predictions of the abstract representation are to accurately match the real world, and the real world is complete and doesn't have any missing causes).

End quote. Cundy goes on to make critical remarks about the “growing block” and “moving spotlight” versions of the A-theory too (albeit not quite as critical since these views do not claim that the present alone is real).

Now, once again it seems to me that Cundy is underestimating how extremely abstract the information contained in the mathematics really is. He seems to be implying that one can read off the equal reality of past, present, and future events from the mathematics itself. And that is simply not the case. You might as well say that you can read off the falsity of presentism from the truth of the sentence “I was in the kitchen a minute ago, am now in my study, and will be in the garage in another minute.” Of course, it does not follow from the truth of this sentence alone that the states of affairs of my being in the kitchen, my being in my study, and my being in the garage are all equally real. To show that, one would need additional, metaphysical argumentation to the effect that the truth of the sentence cannot be accounted for in a presentist way. But the same thing is true of the mathematics of special relativity.

This is precisely why positions like Craig’s neo-Lorentzian presentism, Tooley’s growing block interpretation, etc. can get off the ground at least long enough to require detailed criticism from opponents of the A-theory. The critics typically don’t say that Craig, Tooley, et al. simply fail to understand the implications of the mathematical representation, and then quickly dismiss their positions on that basis. Rather, the critics allow that Craig, Tooley, et al. offer possible interpretations of the mathematics, but then accuse them of having to make ad hoc assumptions, of putting too much stock in independent metaphysical considerations, etc. Again, the point isn’t to endorse any of the specifics of the interpretations defended by Craig, Tooley, et al., but just to emphasize how little the mathematical representation by itselfsettles.

However, I would certainly endorse the view of Craig, Tooley, et al. that it is perfectly legitimate to allow independently motivated metaphysical considerations to guide one’s interpretation of the mathematics. Again, I would say that that is what allsides of the debate – the critics of the A-theory no less than its defenders – are doing, and have to do. Like Dean Zimmerman, Arthur Prior, and other defenders of presentism, I would say that the most that special relativity rules out is a privileged reference frame that is empirically detectable. But that makes the notion of a privileged reference frame objectionable only if one assumes verificationism or some other brand of scientism – which are philosophical positions rather than anything required by the physics, and positions which (I argue) we already have ample reason to reject whatever we think of special relativity. On alternative philosophical positions (such as the Aristotelian one I endorse) we have independent metaphysical grounds to affirm presentism, and it is no less legitimate for the A-theorist to be guided by these grounds when interpreting relativity than it is for critics of the A-theory to interpret relativity in light of their own philosophical assumptions (verificationism, scientism, or whatever).

Nor, contrary to Cundy, does adopting presentism entail that there are aspects of the mathematical representation that correspond to nothing in reality. For there are more ways in which the representation might correspond to reality than the one Cundy supposes. As I note in Aristotle’s Revenge at pp. 269-70, one could say that only the present exists, but that there are in the collection of presently existing objects taken as a whole potentialitiesfor generating future outcomes, including the range of observations that might be made by different observers, of the kind represented by the mathematics of special relativity. That’s a pretty thin kind of realism, to be sure, but as I keep saying, the realism defended by the structural realist is pretty thin in any event.

It is also important to keep in mind that an aspect of a mathematical representation can both correspond to reality in onerespect while in another respect being a mere artifact of the mathematics. A simple and common example would be a statistical claim to the effect that there are 2.5 children in the average family. Such a claim is grounded in reality insofar as if families today had as many children as families tended to have a century ago, the number would have been higher. But at the same time, there is, of course, no family with 2.5 children. That the average number of children per family comes out to be 2.5 is an artifact of the mathematics. In the same way, the empirical success of relativity’s mathematical representation of space and time does not entail that all the points in time it represents are equally real in the way that all the points in space it represents are. The appearance that they are equally real might, for all the utility of the representation shows, merely be (and in my view actually is) an artifact of the mathematics.

Since Cundy puts such emphasis on symmetry and invariance, it is worth pointing out that here too we can have something that is really just an artifact of the representation rather than of physical reality, even when the representation is in some sense grounded in physical reality. As Cundy points out, physics’ representation of space is constructed in two stages. There is a first mapping from physical space to geometrical space, and then a second mapping from geometrical space to coordinate space. Now, consider Euclidean geometrical space. Obviously it has tremendous utility in most everyday contexts, which is why people assumed for so long that it was the correct geometry of physical space. Moreover, there are features of Euclidean space (such as the distance between two points) that remain invariant under different coordinate systems. They show that Euclidean space has a structure that is independent of choice of coordinate systems. Does this invariance coupled with the utility of Euclidean geometry show that the structure of physical reality must correspond to the structure of Euclidean space? Of course not, as every student of relativity would be the first to tell you.

And yet for all that, it remains true that Euclidean geometry wouldn’t have the utility it has if it didn’t capture something about reality. It isn’t just made up out of whole cloth, and wouldn’t work so well if it were. So we aren’t left with instrumentalism, exactly. But the realism we are left with is still extremely thin. Structure tells you something about reality, but not a whole lot, since the correspondence between the structure of a mathematical representation and the structure of reality can be pretty loose. Hence structural realism simply cannot underwrite attempts to read strong metaphysical conclusions off of the mathematical representations employed in physics.

Turning to the B-theory, Cundy disputes my claim that it implies a Parmenidean world that is devoid of change or the actualization of potential. On the contrary, says Cundy, “the four dimensional view allows for actualisation. At one time, state A is actual and state B exists potentially. At a slightly later time, state B is actual and C is potential.” But to appeal to an example used earlier, this is like saying that a stick that is red at one end and green at the other must by virtue of that fact alone be changing its color, since it is potentially green at the first end and actually green at the other. In fact, of course, there is no change at all, because it is not going from red to green but actually is red and green at the same time in different parts.

But the B-theory makes the attributes a thing has at different times essentially like this, and this is so whether or not it spatializes time full stop. For on the B-theory, potentiality does not give way to actuality any more than it does in the stick example. There is no process, but the eternal co-existence of different states. In other words, the B-theory fails to capture real change and real causation for the same reason that, as I argued above, the physicist’s abstract space-time coordinate system, considered by itself, fails to capture them. It eternalizes the series of events and thus strips it of change. There is no actualizing in it, for everything in it is already actual.

Cundy tells us that his own position is neither an A-theory nor a B-theory, but a third sort of view. The reason he is not a B-theorist, he indicates, is that he thinks that time does have a direction, that moments of time do succeed one another, and that tensed language still has utility even though “the notions of now, past, present and future are not objective, but observer dependent.” But B-theorists wouldn’t necessarily deny any of this, so it isn’t clear to me from these remarks how Cundy’s view really is different from a B-theory.

Responses to my arguments

In any event, Cundy does defend the B-theory against some of the criticisms I raise against it. Unfortunately, some of his responses rest on misunderstandings of what I wrote. For instance, when discussing the question whether the B-theory objectionably spatializes time, Cundy accuses me of several errors. He writes:

[Feser says that] The spatial dimensions differ profoundly from time [insofar as] You can rotate in space to convert width to height, but not convert a spatial dimension to a temporal one [and] You use a ruler to measure length and a clock to measure time, but not vice versa.

Both of these statements are false. As mentioned, a Lorentz transformation is the exact analogue of a rotation, mixing time and space coordinates: the differences in the mathematical expression arise solely from that minus sign in the metric…

Secondly, you can use clocks to measure distance. One can, for example, fire a pulse of laser light, have it bounce off a mirror at the end of the target, time how long it takes to make the round trip, and calculate from that and the known speed of light the length of the object. Coupled with an interferometer, this is, in fact, the most precise and accurate way of computing distances.

End quote. The trouble with this is that Cundy has overlooked the context in which I made these remarks. I explicitly said that I was describing “our pre-theoretical or commonsense notions of time and space” (p. 274, emphasis added). So the fact that rotation of the sort in question is possible on relativity’s theoretical model of space and time is irrelevant to the specific point I was making. Furthermore, while you can use clocks as a method for inferring distance, that too does not conflict with what I said, which is that on the commonsense conception of time, you cannot measure distance with a clock in the sense in which you can do so with a ruler. That might seem too obvious to be worth mentioning, but that too is precisely the point. What I was trying to describe is precisely what seems obvious to common sense.

Nor was I saying that the fact that any of this reflects common sense suffices all by itself to show that it is true. The point is just that, before you can determine the extent to which physics either captures, revises, or abandons our ordinary conception of time, you first need (naturally) to determine exactly what our ordinary conception of time involves. That’s what I was doing in that section. Whether physics is or ought to be consistent with our commonsense conception of time is, of course, another question. But the further physics departs from it, the greater is the danger Sklar identifies, viz. that of falling into a fallacy of equivocation when drawing metaphysical conclusions about the nature of time from the physics.

Cundy also seems to me to read some of what I wrote a bit uncharitably. For example, speaking as if he were informing me of something that I didn’t know, he writes that “there is far more to geometry than just lines and planes” and that while “Euclid started defining his geometry from a set of axioms involving lines and circles… we have moved on since then, and now think of geometry in different ways.” Naturally, I am well aware of that. I would have thought it obvious from the context that I was using simple examples as the clearest way to introduce the idea that the mathematical representations utilized by the physicist abstract from concrete reality.

In response to the charge that “the four dimensional view of space time collapses the distinction between time and eternity,” Cundy says:

On the contrary, it maintains it. Time passes for things within the universe, eternity is for those outside it. Temporal beings have a subjective notion of the present, as from inside a B theory universe. The eternal being sees all of reality together, as one would expect from something outside a B theory universe.

End quote. But this not only does not refute the claim that the four-dimensional view collapses time into eternity, if anything it reinforces it. For it seems to amount to nothing more than the point that even if the B-theory is true and all points in time are equally real, time will still appear to pass and there will appear to be a unique present from the subjective point of view of the observer. But nobody denies that much! The question is whether this appearance corresponds to anything in reality outside the subjective point of view of the observer. If you are worried that you are merely hallucinating the pink elephant you think you see in front of you, it is no comfort if I assure you that from your subjective point of view it really does seem to you as if there is a pink elephant there. What you want to know is whether there really is a pink elephant there, not whether there seems to you to be one (you already know that much). Similarly, what is at issue in the debate over the B-theory is whether time really would collapse into eternity on such a theory, not whether it would seem not to.

Cundy’s last two sections respond to my remarks on the implications of relativity, and my reasons for affirming the A-theory. I have already addressed the first of these two topics in my comments above about the metaphysical implications (or lack thereof) of the mathematical representations employed in physics.

In response to the A-theorist’s claim that there are truths that cannot be captured in the tenseless terms favored by the B-theory, Cundy says:

I accept that tense is a real part of the four dimensional universe, but argue that it is subjective rather than objective. Thus for everything within the universe (which includes us), there is indeed a present, past and future. But it is still not an objective feature; which moment is the present depends on when you are in time.

End quote. Once again, it seems to me that Cundy is missing the A-theorist’s point. What is at issue between the A-theory and the B-theory isn’t whether tensed language is necessary in order to describe the way the world seems to us, subjectively. What is at issue is whether tensed language is necessary in order to describe the way it really is, objectively. And Cundy seems to think that such language is notnecessary to do the latter job – in which case he does not after all “accept that tense is a real part of the four dimensional universe.”

In Aristotle’s Revenge, I argue that even if we could eliminate the notion of temporal passage from our description of mind-independent reality, we cannot coherently eliminate it from a description of the mind itself. Hence the notion of temporal passage is ineliminable. Cundy responds:

I think that Professor Feser's argument is compelling to show that the passage of time is a real feature of the world. So this argument works well against those formulations of the B theory which he criticises. But I have been arguing is that there is an alternative four dimensional viewpoint which does accept change and temporal passage. The argument from experience says nothing against this.

End quote. In other respects too, Cundy says, he agrees with my analysis of the experience of time. Here it seems to me that Cundy is not really replying to the A-theory but rather precisely backing himself into a version of the A-theory, namely the “moving spotlight” version that he elsewhere claims to reject. His main reason for rejecting it, he tells us earlier in his article, is that it seems to him an ad hoc and unnecessary addition to the picture of the world given by the B-theory. But it seems to me that Cundy’s acceptance of the ineliminability of temporal passage gives him a non-ad hocreason to endorse it.

Cundy’s position is therefore ambiguous. On the one hand, his affirmation of the equal existence of past, present, and future moments of time and his characterization of tense and presentness as “subjective” seem to imply a B-theory. On the other hand, his Aristotelian-Thomistic commitment to the reality of change as the actualization of potential and his affirmation of the ineliminability of temporal passage seem to point to an A-theory. It appears to me, then, that Cundy may really be a “moving spotlight” theorist without realizing it, or at least that adopting a version of the moving spotlight theory might be the best way for him to make his various commitments cohere.

A lot more could be said, but this post is long enough as it is. I will end by noting that the briefest way to sum up my own position would be as follows. We cannot coherently deny the reality of change and temporal passage, but the B-theory implicitly denies these by effectively collapsing time into eternity. So we should adopt an A-theory instead. Furthermore, given its methodological verificationism and the abstractness of its mathematical representations, physics simply gives us way too thin a description of the world to have much in the way of metaphysical implications. In particular, by itself it gives us no reason to prefer the B-theory to the A-theory. Meanwhile, versions of the A-theory like the growing block theory and the moving spotlight theory make needless and ill-advised concessions to the B-theory, which lack motivation once the problems with that theory are exposed. So, the version of the A-theory we should adopt is presentism, which makes no such concessions.

For the detailed exposition of these lines of argument, see Aristotle’s Revenge. I thank Dr. Cundy for his serious engagement with the book, and in particular for setting out such a clearly reasoned, well-informed, thorough and constructive critical response.

Published on December 20, 2019 14:58

December 17, 2019

New from Oderberg

Fans of David S. Oderberg have long been looking forward to a new book from him, and now it is here – just in time to fill Christmas stockings.

The Metaphysics of Good and Evil

is out this month from Routledge. Details can be found at Routledge’s website. From the cover copy:

Fans of David S. Oderberg have long been looking forward to a new book from him, and now it is here – just in time to fill Christmas stockings.

The Metaphysics of Good and Evil

is out this month from Routledge. Details can be found at Routledge’s website. From the cover copy:The Metaphysics of Good and Evil is the first, full-length contemporary defence, from the perspective of analytic philosophy, of the Scholastic theory of good and evil – the theory of Aristotle, Augustine, Aquinas, and most medieval and Thomistic philosophers. Goodness is analysed as obedience to nature. Evil is analysed as the privation of goodness. Goodness, surprisingly, is found in the non-living world, but in the living world it takes on a special character. The book analyses various kinds of goodness, showing how they fit into the Scholastic theory. The privation theory of evil is given its most comprehensive contemporary defence, including an account of truthmakers for truths of privation and an analysis of how causation by privation should be understood. In the end, all evil is deviance – a departure from the goodness prescribed by a thing’s essential nature.

Published on December 17, 2019 16:06

Science et Esprit on Aristotle’s Revenge

In the latest issue of the journal

Science et Esprit

(Vol. 72, Nos. 1-2), René Ardell Fehr kindly reviews my book

Aristotle’s Revenge

. Judging it a “fine work,” Fehr writes:

In the latest issue of the journal

Science et Esprit

(Vol. 72, Nos. 1-2), René Ardell Fehr kindly reviews my book

Aristotle’s Revenge

. Judging it a “fine work,” Fehr writes:Feser’s book attempts to support the broad Aristotelian metaphysical structure and its interpretation of modern science as the interpretation, while at the same time defending that structure from the attacks of philosophical naturalists and attacking the metaphysical assumptions of said naturalists. It is a credit to Feser that he sees the inherent danger in such a project; throughout Aristotle’s Revenge he insists that he is not attacking modern science itself. Feser writes: “I am not pitting philosophy of nature against physics. I am pitting one philosophy of nature against another philosophy of nature.” Addressing the contents of the book, Fehr says:

Aristotle’s Revenge is comprehensive in that it covers a vast array of arguments, objections, and replies. Often the reader will find Feser dividing objections against his position into different types and treating them all in turn. Objections will be raised to his replies to previous objections, and in like turn they will be dealt with. The sheer number of different positions it confronts is impressive… Those already familiar with the academic work of Feser will be pleased to find the same degree of rigor and the tight argumentation in Aristotle’s Revenge for which he is well known. On display too is the ease of readability which so often characterizes Feser’s work.

Fehr’s main criticism of the book is that, precisely because of the vast amount of ground it covers, some topics could have been pursued at even greater depth, and there are further moves that critics of the various positions I take might make that I do not address. Still, he says:

[This] is an inevitable byproduct of the number of positions and arguments with which Feser grapples… [and] if nothing else his book does an excellent job of alerting the reader to a particular counter-point of view, and to what a preliminary reply might look like.