Edward Feser's Blog, page 44

October 30, 2019

New from Editiones Scholasticae

Editiones Scholasticae, the publisher of my books

Scholastic Metaphysics

and

Aristotle’s Revenge

, informs me that both of them will within a few days be available in eBook versions. Also new from the publisher is a German translation of my book

Philosophy of Mind

. (Previously they had published German translations of

The Last Superstition

and

Five Proofs of the Existence of God

.) Take a look at Editiones Scholasticae’s new webpage for further information, as well as for information about other new releases from the publisher. You will find both new works by contemporary writers in the Scholastic tradition, and reprints of older and long out of print works in that tradition. (The original webpage is still online as well.)

Editiones Scholasticae, the publisher of my books

Scholastic Metaphysics

and

Aristotle’s Revenge

, informs me that both of them will within a few days be available in eBook versions. Also new from the publisher is a German translation of my book

Philosophy of Mind

. (Previously they had published German translations of

The Last Superstition

and

Five Proofs of the Existence of God

.) Take a look at Editiones Scholasticae’s new webpage for further information, as well as for information about other new releases from the publisher. You will find both new works by contemporary writers in the Scholastic tradition, and reprints of older and long out of print works in that tradition. (The original webpage is still online as well.)

Published on October 30, 2019 17:07

October 26, 2019

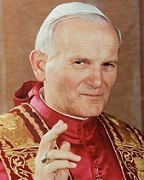

John Paul II in defense of the nation and patriotism

In chapters 11-15 of his last book

Memory and Identity

, Pope St. John Paul II provides a lucid exposition of the idea of the nation as a natural social institution and of the virtue of patriotism, as these have been understood in traditional natural law theory and Catholic moral theology. The relevance to current controversies will be obvious.

In chapters 11-15 of his last book

Memory and Identity

, Pope St. John Paul II provides a lucid exposition of the idea of the nation as a natural social institution and of the virtue of patriotism, as these have been understood in traditional natural law theory and Catholic moral theology. The relevance to current controversies will be obvious.What is the nation, and what is patriotism? John Paul begins by noting the connection between the nation and the family, where the former is in a sense an extension of the latter: The Latin word patria is associated with the idea and the reality of “father” (pater). The native land (or fatherland) can in some ways be identified with patrimony – that is, the totality of goods bequeathed to us by our forefathers… Our native land is thus our heritage and it is also the whole patrimony derived from that heritage. It refers to the land, the territory, but more importantly, the concept of patria includes the values and spiritual content that make up the culture of a given nation. (p. 60)

As that last remark makes clear, the ties of blood are less important than those of culture. Indeed, multiple ethnicities can make up a nation. Referring to his native Poland, the pope notes that “in ethnic terms, perhaps the most significant event for the foundation of the nation was the union of two great tribes,” and yet other peoples too eventually went on together to comprise “the Polish nation” (p. 77). It is shared culture, and especially a shared religion, that formed these diverse ethnicities into a nation:

When we speak of Poland’s baptism, we are not simply referring to the sacrament of Christian initiation received by the first historical sovereign of Poland, but also to the event which was decisive for the birth of the nation and the formation of its Christian identity. In this sense, the date of Poland’s baptism marks a turning point. Poland as a nation emerges from its prehistory at that moment and begins to exist in history. (p. 77)

That a shared culture is the key to understanding the nation is a theme John Paul emphasizes repeatedly throughout the book. He says that “every nation draws life from the works of its own culture” (p. 83), and that:

The nation is, in fact, the great community of men who are united by various ties, but above all, precisely by culture. The nation exists ‘through’ culture and ‘for’ culture and it is therefore the great educator of men in order that they may ‘be more’ in the community…

I am the son of a nation which… has kept its identity, and it has kept, in spite of partitions and foreign occupations, its national sovereignty, not by relying on the resources of physical power but solely by relying on its culture. This culture turned out, under the circumstances, to be more powerful than all other forces. What I say here concerning the right of the nation to the foundation of its culture and its future is not, therefore, the echo of any ‘nationalism’, but it is always a question of a stable element of human experience and of the humanistic perspective of man's development. There exists a fundamental sovereignty of society, which is manifested in the culture of the nation. (p. 85)

In addition to shared values and religion, John Paul identifies shared history as another crucial aspect of a nation’s identifying culture:

Like individuals, then, nations are endowed with historical memory… And the histories of nations, objectified and recorded in writing, are among the essential elements of culture – the element which determines the nation’s identity in the temporal dimension. (pp. 73-74)

The pope notes that citizens of modern Western European countries often have “reservations” about the notion of “national identity as expressed through culture,” and have even “arrived at a stage which could be defined as ‘post-identity’” (p. 86). There is “a widespread tendency to move toward supranational structures, even internationalism” with “small nations… allow[ing] themselves to be absorbed into larger political structures” (p. 66). However, the disappearance of the nation would be contrary to the natural order of things:

Yet it still seems that nation and native land, like the family, are permanent realities. In this regard, Catholic social doctrine speaks of “natural” societies, indicating that both the family and the nation have a particular bond with human nature, which has a social dimension. Every society’s formation takes place in and through the family: of this there can be no doubt. Yet something similar could also be said about the nation. (p. 67)

And again:

The term “nation” designates a community based in a given territory and distinguished from other nations by its culture. Catholic social doctrine holds that the family and the nation are both natural societies, not the product of mere convention. Therefore, in human history they cannot be replaced by anything else. For example, the nation cannot be replaced by the State, even though the nation tends naturally to establish itself as a State… Still less is it possible to identify the nation with so-called democratic society, since here it is a case of two distinct, albeit interconnected orders. Democratic society is closer to the State than is the nation. Yet the nation is the ground on which the State is born. (pp. 69-70)

As this last point about the state and democracy indicates, a nation cannot be defined in terms of, or replaced by, either governmental institutions and their laws and policies on the one hand, or the aggregate of the attitudes of individual citizens on the other. It is something deeper than, and presupposed by, both of these things. It is only insofar as a nation, defined by its culture, is already in place that a polity can come into being. Hence it is a mistake to think that, if the common cultural bonds that define a nation disappear, the nation can still be held together by virtue of governmental policy either imposed from above or arrived at my majority vote. For a people have to be united by common bonds of culture before they can all see either governmental policy or the will of the majority as legitimate. (Readers familiar with the work of Roger Scruton will note the parallels, and how deeply conservative John Paul II’s understanding of the nation is.)

Now, as a natural institution, the nation, like the family, is necessary for our well-being. And as with the family, this entails a moral duty to be loyal to and to defend one’s nation – and for precisely the same sorts of reasons one has a duty of loyalty to and defense of one’s family:

If we ask where patriotism appears in the Decalogue, the reply comes without hesitation: it is covered by the fourth commandment, which obliges us to honor our father and mother. It is included under the umbrella of the Latin word pietas, which underlines the religious dimension of the respect and veneration due to parents…

Patriotism is a love for everything to do with our native land: its history, its traditions, its language, its natural features. It is a love which extends also to the works of our compatriots and the fruits of their genius. Every danger that threatens the overall good of our native land becomes an occasion to demonstrate this love. (pp. 65-66)

Among the dangers to the nation are the opposite extreme economic errors of egalitarian statism and liberal individualism, which threaten to destroy the common culture that defines the nation – in the one case from the top down and in the other from the bottom up. The pope writes:

[W]e must ask how best to respect the proper relationship between economics and culture without destroying this greater human good for the sake of profit, in deference to the overwhelming power of one-sided market forces. It matters little, in fact, whether this kind of tyranny is imposed by Marxist totalitarianism or by Western liberalism. (pp. 83-84)

If liberal individualism is an error that pays insufficient respect to the nation, there is of course an opposite extreme error which involves giving excessive esteem to the nation – namely, nationalism. Patriotism, rightly understood, is the middle ground between these extremes:

Whereas nationalism involves recognizing and pursuing the good of one’s own nation alone, without regard for the rights of others, patriotism, on the other hand, is a love for one’s native land that accords rights to all other nations equal to those claimed for one’s own. (p. 67)

John Paul II was clear that the remedy for nationalism was not to go to the opposite extreme (whether in the name of individualism, internationalism, or whatever), but rather precisely to insist on the sober middle ground:

How can we be delivered from such a danger? I think the right way is through patriotism… Patriotism, in other words, leads to a properly ordered social love. (p. 67)

Now, let’s note a number of things about these remarks and their implications. First, as I have said, what the late pope was giving expression to here is not merely his personal opinion, but traditional natural law political philosophy and Catholic moral teaching – the kind of thing that would have been well known to someone formed in Thomistic philosophy and theology in the early twentieth century, as John Paul II was.

Second, John Paul’s teaching implies that those who seek to preserve their nation’s common culture, and for that reason are concerned about trends that might radically alter its religious makeup or undermine its common language and reverence for its history, are simply following a natural and healthy human impulse and indeed following out the implications of the fourth commandment. There is no necessary connection between this attitude and racism, hatred for immigrants, religious bigotry, or the like.

Of course, a person who seeks to preserve his nation’s culture might also be a racist or xenophobe or bigot. The point, however, is that he need not be, and indeed that it is wrong even to presume that he is, because a special love for one’s own nation and desire to preserve its culture is a natural human tendency, and thus likely to be found even in people who have no racist or xenophobic or bigoted attitudes at all. Indeed, it is, again, even morally virtuous.

Needless to say, there is also a moral need to balance this patriotism with a welcoming attitude toward immigrants, with respect for the rights of religious minorities, and so forth. The point, however, is that all of these things need to be balanced. Too many contemporary Catholics, including some churchmen, have a tendency to emphasize only the latter while ignoring the former. They have a tendency to buy into the leftist narrative according to which the current wave of populist and patriotic sentiment in the United States and Western Europe is merely an expression of racism and xenophobia. This is deeply unjust, contrary to Catholic teaching, and politically dangerous. It is unjust and contrary to Catholic teaching because, again, both natural law and traditional moral theology affirm that a desire to preserve one’s nation and its culture are natural human sentiments and morally praiseworthy. It is dangerous because, when governing authorities fail to respect and take account of these natural and decent human sentiments, they are inviting rather than preventing a nationalist overreaction.

(President Trump has famously called himself a “nationalist,” which is unfortunate given the connotations of that term. However, from his 2019 address to the United Nations it seems clear that what he means by this is just the defense of the institution of the nation against those who would dissolve it in the name of globalism, open borders, etc. Moreover, he explicitly affirmed the right of every nation to preserve itself and its sovereignty, and the right of everyhuman being to have a special patriotic love and preference for his own country. He also has repeatedly called for the United States to refrain from intervening in the affairs of other nations. So it is evident that it is really just patriotism in the sense described above, rather than some sort of American nationalism, that he intends to promote.)

The current controversy over illegal immigration must be understood in light of these principles. In a 1996 message on World Migration Day, John Paul II emphasized the need to welcome migrants, to take account of the dangerous circumstances they are sometimes fleeing, to avoid all racist and xenophobic attitudes, and so on. At the same time, he acknowledged that “migration is assuming the features of a social emergency, above all because of the increase in illegal migrants” (emphasis in the original), and that the problem is “delicate and complex.” He affirmed that “illegal immigration should be prevented” and that one reason it is problematic is that “the supply of foreign labour is becoming excessive in comparison to the needs of the economy, which already has difficulty in absorbing its domestic workers.” And he stated that in some cases, it may be necessary to advise migrants “to seek acceptance in other countries, or to return to their own country.”

The Catechism promulgated by Pope John Paul II teaches that:

The more prosperous nations are obliged, to the extent they are able,to welcome the foreigner in search of the security and the means of livelihood which he cannot find in his country of origin. Public authorities should see to it that the natural right is respected that places a guest under the protection of those who receive him.

Political authorities, for the sake of the common good for which they are responsible, may make the exercise of the right to immigrate subject to various juridical conditions, especially with regard to the immigrants' duties toward their country of adoption. Immigrants are obliged to respect with gratitude the material and spiritual heritage of the country that receives them, to obey its laws and to assist in carrying civic burdens. (Emphasis added)

End quote. Note that the Catechism teaches that immigrants have a duty to respect the laws and “spiritual heritage” of the nation they seek to enter, and that political authorities may restrict immigration so as to uphold the “common good” of the nation they govern.

Hence, there is no foundation in Catholic teaching for an open borders position, or for the position that those who seek to uphold the common culture and economic interests of their nation ought to be dismissed as racists and xenophobes. On the contrary, Catholic teaching explicitly rules out those positions.

There is a further implication of John Paul II’s teaching. It isn’t merely that having a special love for one’s nation and its culture is natural and virtuous. It is that a failure to have it is vicious – a violation of the fourth commandment.

Of course, every nation has its faults, and aspects of its history of which one ought to be ashamed. For example, Germans are right to repudiate the Nazi period of their history, and Americans are right to repudiate slavery and segregation. But there is a mentality prevalent in the modern West that goes well beyond that – that insists on seeing nothing but evil in one’s own nation and its culture and history. This is the mentality sometimes called oikophobia – the hatred of one’s own “household” (oikos), in the sense of one’s own nation. One sees this mentality in Westerners who shrilly and constantly denounce their civilization as irredeemably racist, colonialist, etc., downplaying or denying its virtues, and comparing it unfavorably to other cultures – as if Western culture is somehow more prone to such failings than other cultures are, and as if it hasn’t contributed enormously to the good of the world (both of which are absurd suppositions).

Oikophobia is evil. It is a spiritual poison that damages both those prone to it (insofar as it makes them bitter, ungrateful, etc.) and the social order of which they are parts (insofar as it undermines the love and loyalty citizens need to have for their nation if it is to survive). It is analogous to the evil of hating and undermining one’s own family. It is a violation of the fourth commandment.

The oikophobe sees his position as a remedy for nationalism, but in fact he is simply guilty of falling into an error that is the opposite extreme from that of the nationalist. Moreover, he is inadvertently promoting nationalism, because human beings have a tendency to overreact to one extreme by going too far in the other direction. Nationalism is bound to arise precisely as an overreaction against oikophobia. Those who are currently reacting to what they perceive as a resurgent nationalism by doubling down on oikophobia – pushing for open borders, indiscriminately denouncing their opponents as racists and xenophobes, etc. – are making a true nationalist backlash more likely, not less likely. The only true remedy for the evils of nationalism and oikophobia is, as John Paul II taught, the sober middle ground of patriotism.

It is no accident that those prone to oikophobia tend to be precisely the same people as those who want to push further the sexual revolution, feminism, and the destruction of the traditional family and traditional sex roles that these entail. The same liberal individualist poison is at the core of all of these attitudes. As St. John Paul II said, “patria is associated with the idea and the reality of ‘father’ (pater).” Hatred of masculinity and of the paternal authority and responsibilities that are its fulfilment, hatred of the traditional family and of the sexual morality that safeguards it, and hatred of one’s fatherland, are ultimately of a piece. And lurking beneath them all is a deeper hatred for another, heavenly Father.

Further reading:

Liberty, equality, fraternity?

Continetti on post-liberal conservatism

Hayek’s Tragic Capitalism

Published on October 26, 2019 14:18

October 19, 2019

Masculinity and the Marvel movies

Some time back, John Haldane gave a Thomistic Institute talk here in Los Angeles on the theme of evil in the movies and in the movie industry. During the Q and A (at about the 40 minute mark, and again after the 1:16 mark) the subject of superhero movies came up, and Haldane was critical of their current prevalence. In developing this criticism, he draws a useful distinction between fantasyand imagination. Imagination, as Haldane uses the term, is a way of exploring aspects of reality and possibilities that are grounded in reality, even though it makes use of scenarios that are fictional or even impossible. Imagination is healthy and can increase our understanding of the moral and social worlds. Fantasy, by contrast, is unanchored in reality, and indeed it reflects a flight from reality and the discipline it imposes and responsibility that it entails. Haldane gives as an example the movie Pretty Woman, an absurdly unrealistic portrayal of prostitution and human relationships.

Some time back, John Haldane gave a Thomistic Institute talk here in Los Angeles on the theme of evil in the movies and in the movie industry. During the Q and A (at about the 40 minute mark, and again after the 1:16 mark) the subject of superhero movies came up, and Haldane was critical of their current prevalence. In developing this criticism, he draws a useful distinction between fantasyand imagination. Imagination, as Haldane uses the term, is a way of exploring aspects of reality and possibilities that are grounded in reality, even though it makes use of scenarios that are fictional or even impossible. Imagination is healthy and can increase our understanding of the moral and social worlds. Fantasy, by contrast, is unanchored in reality, and indeed it reflects a flight from reality and the discipline it imposes and responsibility that it entails. Haldane gives as an example the movie Pretty Woman, an absurdly unrealistic portrayal of prostitution and human relationships.Fantasy can be harmless in small doses, Haldane allows, but when a culture becomes dominated by it, that is a sign that it has become decadent and unwilling to face reality. And the prevalence of superhero movies, Haldane says, is an indication that American society is increasingly retreating into fantasy and away from reality. He rejects the suggestion that such movies can be compared to the myths of the gods in ancient cultures. Such myths, he says, are essentially exercises in imagination, whereas superhero movies are sheer fantasy.

I think there is some truth to this analysis, but only some. Some superhero movies are indeed exercises in fantasy, but some are, in my view, clearly exercises in imagination.

Not long after hearing Haldane’s talk, I happened to come across a 1978 television interview with the late Harlan Ellison during which (beginning just before the 5 minute mark) Ellison criticizes the movies Close Encounters of the Third Kind and Star Wars, and modern American society in general, on exactly the same grounds raised by Haldane. He doesn’t use Haldane’s terminology, and in fact partially inverts it. Ellison uses “fantasy” to mean what Haldane means by “imagination,” and he uses the expression “space opera” to refer to one type of what Haldane calls “fantasy.” But in substance, the distinction and the sort of points Haldane and Ellison are making are identical.

(Side note: Remember when you could find extended intelligent discussion like this on television? Remember when you could casually smoke on television, as Ellison does during the interview? Remember Laraine Newman, another guest on the show who also contributes to the discussion?)

Interestingly, though, Ellison was also well-known to be an enthusiast for comics, including superhero comics, and even wrote them from time to time (though this doesn’t come up in the interview). I don’t think there is any inconsistency there.

Suppose that, like me and like Haldane (though unlike Ellison) you are a conservative Catholic. Then, I would suggest, it is easy to see that there are themes in many superhero movies, and especially in the Avengers series that is currently the most popular of all, that are clearly reflections of imagination rather than fantasy.

Take the characters who, in the Avengers movies as in the comics, have been regarded as “the Big Three”: Captain America, Thor, and Iron Man. Captain America represents patriotism, the military virtues, the earnest decency of the common man, and in general a Norman Rockwell style nostalgia for a simpler time. Thor – as part of the Asgardian pantheon ruled by stern Odin, to whom he must prove his worthiness – represents the higher realm spoken of by religion, and our obligations to the divine patriarchal authority who governs it. Iron Man is a business magnate who represents confident masculinity, superior ability and great wealth, and the noblesse obligeand rebuke to egalitarianism implied by them. These are deeply conservative themes, and it is astounding that these characters are as popular as they are in a society increasingly suffocated by political correctness.

Or maybe not. For such themes have appeal because they reflect human nature, and human nature does not change however much we try to paper over it with ideology and propaganda, and however corrupt human behavior and human societies become as a result. People will yearn in at least an inchoate way for the traditional institutions and ideals without which they cannot fulfill their nature, even when they are told they ought not to and have halfway convinced themselves that they ought not to.

I would suggest that the Marvel movies have the appeal they do at least in part precisely because they both convey these traditional ideals, but do so in a way that is fantastic enough that the offense to political correctness is not blatant. A film series whose heroes are a square patriotic soldier, the son of a heavenly Father come to earth, and a strutting capitalist alpha male sounds like something tailor-made for a Red State audience, and the last thing that would attract A-list actors and billions in investment from a major studio. Put these characters in colorful costumes, scenarios drawn from science fiction, and a little PC window dressing (such as portraying their girlfriends as a soldier, a scientist, and a businesswoman, respectively), and suddenly even a Blue State crowd can get on board.

Now, there are no traditional ideals more battered in contemporary Western society than masculinity, and the paternal role that is the fulfilment of masculinity. But these are precisely the key themes of many of the Marvel movies. The longing for a lost father or father figure is the core of all of the Spider-Man movies, as I noted in a post from a few years back. (In the Spider-Man movies that have appeared since that post was written, Tony Stark has become the father figure whose instruction and example Peter Parker strives to live up to.) The theme is also central to the Guardians of the Galaxy series, to Black Panther, to the Daredevil movie and Netflix series, and to the Luke Cage and Iron Fist Netflix series. The Thormovies are largely about the conflicted relationships Thor and Loki have with their father Odin, whose approval each of them nevertheless seeks. The bad consequences of rebellion against a father or father figure is the theme of the original Spider-Man series (wherein Peter initially refuses to heed his Uncle Ben’s admonitions), of the first Thormovie, and of Avengers: Age of Ultron(whose wayward son is the robotic Ultron, at odds with his “father” Stark).

The Hulk movies are largely about the consequences of failure as a father (whether Bruce Banner’s father in the original Hulk movie, or Betty Ross’s father in The Incredible Hulk). Ant-Manis essentially about two men (Scott Lang and Hank Pym) who have partially failed as fathers and are trying to make up for it. The Punisher Netflix series is essentially about a husband and father seeking vengeance for the family that was taken from him.

But it is the two stars of the Marvel movies – Tony Stark/Iron Man and Steve Rogers/Captain America – who are the most obvious examples of idealized masculinity. And their character arcs through the series are about realizing that ideal. Each of them starts out as an imperfect specimen of the masculine ideal, albeit in very different ways. With Stark it is a vice of deficiency and with Rogers it is a vice of excess. But by the end of their arcs, in Avengers: Endgame, each achieves the right balance. (It might seem odd to think of Rogersrather than Stark as the one prone to a kind of excess. Bear with me and you’ll see what I mean.)

On the traditional understanding of masculinity, a man’s life’s work has a twofold purpose. First, it is ordered toward providing for his wife and children. Second, it contributes something distinctive and necessary to the larger social order of which he and his family are parts. Society needs farmers, butchers, tailors, manual laborers, soldiers, scholars, doctors, lawyers, etc. and a man finds purpose both by being a husband and father and by filling one of these social roles. Though the traditional view regards women as “the weaker sex” and as less assertive than men, it understands a man’s worth and nobility in terms of the extent to which his strength and assertiveness are directed toward the service of others.

Liberal individualism, both in its libertarian form and its egalitarian form, replaced this social and other-directed model of a man’s life’s work with an individualist and careerist model, on which work is essentially about self-expression and self-fulfillment – making one’s mark in the world, gaining its attention and adulation, attaining fame, power and influence, and so forth. Nor is it even about providing for wife and children, since sex and romance too came to be regarded as a means of self-fulfillment rather than the creation of the fundamental social unit, the family. (Feminism took this corrupted individualist understanding of the meaning of a man’s work and relationships and, rather than critiquing it, urged women to ape it as well.)

In the first two Iron Man movies, Stark is initially a specimen of this individualist mentality. His work is oriented toward attaining wealth, fame, and power. He uses women as playthings. He has a conflicted relationship with his late father, and is contemptuous of authority in general. He is judged by SHIELD to be “volatile, self-obsessed, and [unable to] play well with others.” But he is gradually chastened by the consequences of his hubris – by being captured and injured in the first Iron Man movie; by being forced to face up to the limitations on his power to stop an alien invasion like the one that occurred in Avengers; and by the miscalculation that led to Ultron’s rebellion and the many deaths it caused. By Captain America: Civil War, Stark is humbled enough to accept government oversight, and being left defeated and near-dead by Thanos in Avengers: Infinity War completes his chastening.

By Avengers: Endgame Stark has become a family man. By way of time travel, he makes peace of a sort with his father. In the first Avengers movie, he had casually dismissed Rogers’ talk of the need for self-sacrifice with the confidence that an alternative solution would always be possible for a clever person like himself. By contrast, in Endgame, he sees that he needs to lay down his life in order to save his wife and daughter and the world in general, and he willingly does it. To be sure, he is in no way neutered. He retains his masculine assertiveness, strength, and self-confidence. But they are now directed toward the service of something larger than himself.

Rogers, by contrast, is from the first Captain America movie onward driven by a sense of duty to his country and to the social order more generally, and is willing to sacrifice everything for it, including even his own happiness and indeed his own life. He is also a perfect gentleman, and his only interest where women are concerned is with the one he would like to marry and settle down with if only he had the chance. Like Stark, he is relentlessly assertive, confident, and competent, but unlike Stark these traits are from the start directed toward the service of a larger good.

Rogers’ flaw is that he is if anything a bit tooabsorbed in this larger good. At least initially, he is too much the man of action and the good soldier, with all the virtues but also with the flaws that that entails. He is a little too deferential to authority. In the first Avengers movie he glibly asserts: “We have orders. We should follow them” – only to find out that perhaps he should have questioned them. The way institutions and authorities can become corrupted is impressed upon him far more dramatically in Captain America: Winder Soldier, to the point that in Civil War it is Rogers who is urging Stark to be more skeptical of authority.

In general, Rogers’ optimistic “can do” spirit sometimes borders on naïveté, and it takes the catastrophe of Infinity War to teach him that the good guys don’t always win and that some problems can only be managed or mitigated rather than solved. For much of the series, Rogers also has little life outside some military or quasi-military organization – the army, SHIELD, the Avengers. Without a war to fight, he doesn’t know what to do with himself. He is square, prone to speechifying, and awkward with women – in Winter Soldier proclaiming himself “too busy” for romance, preferring to lose himself in one mission after the other. Only after near-death and victory in a “mother of all battles” in Endgamedoes he become convinced that he has the right to retire and “try some of that life Tony was telling me to get” – traveling back in time to marry the woman he thought he’d lost forever.

The theme of the parallels and differences between the two characters provides a backbone to the Marvel movies. Both Stark and Rogers are supremely confident and competent. They are both natural leaders. Each stubbornly insists on pursuing the course he is convinced is the correct one. They are too similar in these respects – though also too different in the other ways just described – to like each other much at first. The world is not big enough for both egos. They learn to like and respect each other only gradually, through many ups and downs.

Hence, in the first Avengers movie, Stark is jealous of the admiration that his father had had for Rogers, and Rogers is amazed that Howard Stark could have had a son as frivolous and unworthy as Tony. By Civil War, Rogers ends up having to defend the man who had (under mind control) murdered Howard – defending him from Tony, who seeks to avenge his father and now (temporarily) judges Rogers unworthy of his father’s admiration. Stark starts out arrogantly rejecting any government control over his activity as Iron Man, only to insist on government control in Civil War. Rogers starts out dutifully following orders in the first Captain America and Avengers movies, only stubbornly to reject government control over the team in Civil War. In Age of Ultron, Rogers criticizes Stark for acting independently of the team, and in Civil War, Stark criticizes Rogers for acting independently of the team. Rogers feels guilt for failing to prevent the death of Bucky, his comrade-in-arms. Stark feels guilt for failing to prevent the death of Peter Parker, to whom he has become a father figure. Rogers lays down his life in the first Captain America movie, only to get it back. Stark preserves his life against all odds throughout the whole series, only to lay it down in the last Avengers movie.

I submit that its complex portrayal of these competing models of masculinity is part of what makes the Marvel series of movies a genuine exercise in imagination rather than fantasy, in Haldane’s sense of the terms.

One wonders, however, whether this will last. A few years ago, Marvel’s comics division notoriously reoriented their titles to reflect greater “diversity” and political correctness – an experiment that critics labeled “SJW Marvel” and that resulted in a dramatic decline in sales. The trend has been partially reversed and did not at the time affect the movies, where much more money is at stake. But there are signs that a milder form of the “SJW Marvel” approach will make its way into the Marvel Cinematic Universe in the next phase of movies.

For example, the title character of Captain Marvelis portrayed with little emotion, no love interest, and lacking any of the femininity, vulnerability, and complexity of characters like Scarlett Johannsen’s Black Widow or Elizabeth Olsen’s Scarlet Witch. As Kyle Smith noted in National Review, Brie Larson portrays her instead as “fiercer than fierce, braver than brave… insouciant, kicking butt, delivering her lines in an I-got-this monotone… amazingly strong and resilient at the beginning, middle, and end. This isn’t an arc, it’s a straight line.” Into the bargain, this C-list character, dropped into the Marvel Cinematic Universe out of nowhere, is suddenly proclaimed “the most powerful character” in that universe.

In short, Captain Marvel is transparently an exercise in feminist wish fulfilment. More to the present point, it is sheer fantasy in Haldane’s sense, rather than imagination – a portrayal of the way a certain mindset wishes the world to be, rather than a fanciful representation of the way it really is. And, as Smith points out, its title character is for that reason completely boring. (Contrast this with Marvel’s Netflix series Jessica Jones, which – despite its own feminist undercurrents – is not boring, and whose female characters are well-rounded and interesting.)

If future Marvel movies follow in this identity politics oriented direction, they will in fact become what Haldane (in my view mistakenly) thinks they already are.

Further reading:

Pop culture roundup

Published on October 19, 2019 13:09

October 11, 2019

Around the web

At The Catholic Thing, Fr. Thomas Weinandy on the studied ambiguity of Pope Francis. In his new book Conciliar Octet, Fr. Aidan Nichols on the hermeneutic of continuity and Vatican II.

At The Catholic Thing, Fr. Thomas Weinandy on the studied ambiguity of Pope Francis. In his new book Conciliar Octet, Fr. Aidan Nichols on the hermeneutic of continuity and Vatican II. At Medium, philosopher Kathleen Stock on gender theory versus academic freedom in the UK. At Inside Higher Education, twelve prominent philosophers defend the right to free inquiry on matters of sex and gender.

Philosopher Daniel A. Kaufman on the “woke” fanatics increasingly infesting academic philosophy, at The Electric Agora. Richard Marshall interviews Kaufman at 3:16. Peggy Noonan on transgender Jacobinism , at The Wall Street Journal. At YouTube, video of an indoctrination session .

Jacob Howland on Borges’s Library of Babel, at The New Criterion.

At New Statesman, John Gray on Tom Holland on the Christian origins of modern secular liberal values . More reviews at The University Bookman and at Literary Review .

At Quillette, Benedict Beckeld diagnoses Western self-hatred or oikophobia.

Donald Fagen interviewed on Paul Shaffer Plus One.

Kay Hymowitz on the sexual revolution and mental health, at The Washington Examiner.

John DeRosa of the Classical Theism Podcast interviews Thomist philosopher Gaven Kerr on the topic of Aquinas and creation.

Ronald W. Dworkin on “artificial intelligence” as a projection of artificial intelligence researchers, at The American Interest.

New books on Aquinas: Aquinas and the Metaphysics of Creation , by Gaven Kerr; The Discovery of Being and Thomas Aquinas , edited by Christopher Cullen and Franklin Harkins; The Human Person: What Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas Offer Modern Psychology , by Thomas Spalding, James Stedman, Christina Gagné, and Matthew Kostelecky.

At the Institute of Art and Ideas: Philosopher of physics Tim Maudlin on quantum physics and common sense. Physicist Subir Sarkar and philosophers Nancy Cartwright and John Dupré discuss physics and materialism.

Philosopher Dennis Bonnette on the distinction between the intellect and the imagination, at Strange Notions.

Philosopher of time Ross Cameron is interviewed by Richard Marshall at 3:16.

Duns Scotus in focus at Philosophy Now and Commonweal .

10 facts about Alfred Hitchcock Presents, at Mental Floss.

Tim Maudlin on Judea Pearl on causation versus correlation, at the Boston Review. Maudlin’s book Philosophy of Physics: Quantum Theory is reviewed at Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews.

Charles Styles interviews Peter Harrison on the subject of the best books on the history of science and religion, at Five Books.

At Quillette, Kevin Mims on The Exorcist as a film about the breakdown of the family .

Society in Mind on the replication crisis in psychology.

Matias Slavov on Hume and Einstein on the nature of time, at Aeon.

At Catholic World Report, philosopher Joseph Trabbic on Aquinas and political liberalism.

Boston Review on post-liberal academic political philosophy. The Chronicle of Higher Educationon post-liberal Catholic political philosophy.

Blue World , an album of lost John Coltrane tracks, has been released.

It’s a thing. The Huffington Post reports on millennials who are becoming nuns.

Scott Alexander on LGBT as a new civil religion, at Slate Star Codex . C. C. Pecknold on the phony neutrality of post-Obergefell liberalism, at Catholic Herald.

Published on October 11, 2019 16:48

October 9, 2019

Transubstantiation and hylemorphism

One of the key themes of the early modern philosophers’ revolt against Scholasticism was a move away from an Aristotelian hylemorphist conception of the nature of physical substance to some variation or other of the mechanical philosophy. The other day I was asked a very interesting question: Can transubstantiation be formulated in terms of a mechanistic conception of physical substance rather than a hylemorphic one? My answer was that I would not peremptorily say that it cannot be, but that the suggestion certainly raises serious philosophical and theological problems. Here’s why. Hylemorphism in its most straightforward version roughly agrees with common sense about which of the things of everyday experience are distinct substances, which are different parts of the same substance, and which are aggregates rather than true substances. For example, it would say that a stone, a tree, and a dog are all distinct substances from one another; that a particular dog’s nose and its right front leg are different parts of the same substance rather than distinct substances; and that a pile of stones is an aggregate rather than a substance in its own right. Of course, use of the term “substance” in the technical Aristotelian sense isn’t part of common sense, but even untutored common sense would surely involve the supposition that a stone, a tree, and a dog are all distinct things or objects, that the nose and leg of the dog are parts of a larger thing or object rather than separate things or objects, and that a pile of stones is a bunch of things or objects rather than a single object. At least to that extent, common sense would more or less agree with what I am calling a straightforward version of hylemorphism. (See chapter 3 of

Scholastic Metaphysics

for exposition and defense of the hylemorphist account of substance.)

One of the key themes of the early modern philosophers’ revolt against Scholasticism was a move away from an Aristotelian hylemorphist conception of the nature of physical substance to some variation or other of the mechanical philosophy. The other day I was asked a very interesting question: Can transubstantiation be formulated in terms of a mechanistic conception of physical substance rather than a hylemorphic one? My answer was that I would not peremptorily say that it cannot be, but that the suggestion certainly raises serious philosophical and theological problems. Here’s why. Hylemorphism in its most straightforward version roughly agrees with common sense about which of the things of everyday experience are distinct substances, which are different parts of the same substance, and which are aggregates rather than true substances. For example, it would say that a stone, a tree, and a dog are all distinct substances from one another; that a particular dog’s nose and its right front leg are different parts of the same substance rather than distinct substances; and that a pile of stones is an aggregate rather than a substance in its own right. Of course, use of the term “substance” in the technical Aristotelian sense isn’t part of common sense, but even untutored common sense would surely involve the supposition that a stone, a tree, and a dog are all distinct things or objects, that the nose and leg of the dog are parts of a larger thing or object rather than separate things or objects, and that a pile of stones is a bunch of things or objects rather than a single object. At least to that extent, common sense would more or less agree with what I am calling a straightforward version of hylemorphism. (See chapter 3 of

Scholastic Metaphysics

for exposition and defense of the hylemorphist account of substance.)Now, the mechanical world picture that pushed aside the hylemorphist model tended radically to revise the common sense understanding of physical objects in one of two general ways, depending on how mechanism was spelled out. It reduced ordinary physical objects either to mere aggregates of their innumerably many component parts, or to mere modes of some larger blob of which theywere the parts.

Descartes and Spinoza essentially took the latter option. Though Descartes is often described as positing a plurality of extended substances alongside the plurality of thinking substances, his considered view seemed to be that strictly speaking, there is only a single extended substance, of which the ordinary objects of our experience are merely modifications. Spinoza more famously took such a position (or rather, he took it that Deus sive Naturawas the one substance of which the ordinary physical objects of our experience are all modes). On this view, a stone, a tree, and a dog are not really distinct substances, but merely distinct aspects of one and the same substance – in something like the way common sense regards the color, weight, and shape of a stone to be mere modes of one and the same object, the stone.

Atomist and corpuscularian versions of the mechanical philosophy went in the other direction. They essentially make either atoms or corpuscles the true substances, and ordinary objects mere aggregates of these purported substances. Just as a pile of rocks is not a true substance but merely a collection of substances (or as the hylemorphist would say, being a pile of rocks is a merely accidental form rather than a substantial form), so too a stone, a tree, or a dog is on this view merely a collection of particles. In effect, the particles are the true substances, and the stone, tree, or dog is like the pile – a relatively superficial arrangement of metaphysically more fundamental entities.

So, to come to transubstantiation, the idea, of course, is that in the Eucharist, while the accidents of bread and wine remain, the substance of bread and wine are miraculously replaced with that of Christ. Suppose, then, that we were to adopt Descartes’ version of the mechanical philosophy, on which there is just one big physical substance underlying all the things ordinary perceptual experience reveals to us. That would entail that the substance that underlies the accidents of bread and wine that are about to be consecrated is the very same substance as that which underlies stones, trees, dogs, cats, human bodies, apples, oranges, the sun, the moon, water, lead, gold, and every other thing we see, hear, taste, touch, or smell.

But in that case, when transubstantiation occurs, it is not just the substance underlying the accidents of bread and wine that is replaced, but the substance underlying all of these other things too. In other words, after transubstantiation occurs, it is really the body and blood of Christ that underlies what we perceive as stones, trees, dogs, cats, human bodies, the sun, the moon, water, etc.! Everything in the physical world would be transubstantiated. We would be left with a kind of pantheism. Absolutely every physical thing would have to treated with the same reverence that the Eucharist is, because every physical thing would be the Eucharist!

Another bizarre implication of this is that transubstantiation could occur only once. For only at the first time it occurs is the one physical substance replaced by that of Christ. If a priest were ever to try to consecrate bread and wine again, he would fail, because there is no longer any physical substance there to be replaced. It is alreadythe body and blood of Christ.

Suppose we went the other route, that of either atomism or corpuscularianism. Then, like stones, trees, and dogs, bread and wine would not be true substances but merely accidental collections of innumerably many true substances. They would be like a pile of rocks, only instead it would be fundamental particles (atoms or corpuscles, depending on your favored version of the mechanical philosophy) that would be piled up. But in that case, exactly what is the substance that is replaced when transubstantiation occurs? Neither the substance of the bread nor that of the wine can be what is replaced, because on this view they just aren’ttrue substances in the first place.

Should we say that it is each particle that makes up the aggregate that is transubstantiated (just as Catholic theology allows that many hosts at a time may be consecrated at Mass)? But there are several problems with that suggestion. The first is that it is hard to know how to give a principled answer to the question what the boundaries are between those particles that make up the aggregate and those that are not part of it – and thus between those particles that are transubstantiated, and those that are not. The reason is that the boundaries of an aggregate are much less well defined than those of a substance. Is a stone that is two millimeters away from a pile of stones itself part of the pile or not? And is a particle that falls from the host part of that (purported) aggregate of particles or not?

If we think of the host on the model of an Aristotelian substance, then we can say that a fallen particle is part of the host, like a body part that has been severed, as it were. But, again, if instead we think in terms of the model of a pile of stones or some other aggregate, the answer isn’t as clear.

A second problem is that in Catholic theology, not any old matter can be used when consecrating the Eucharist. It has to be bread and wine, specifically. But on the interpretation under consideration, according to which bread and wine are not true substances, it is really the particles (either atoms or corpuscles) that are being consecrated. And the atoms or corpuscles that make up bread and wine are essentially the same as those that make up everything else (just as the stones that make up a pile can be essentially of the same type as those that are used instead to make up a wall). In that case, though, it would be hard to see why there is anything special about bread and wine. Why couldn’t any old physical thing be consecrated, if every physical thing is essentially just the same kind of stuff in relatively superficial differences of configuration?

A third problem is that canon law says that a Catholic ought to receive communion at most only once (or in some special circumstances, perhaps twice) a day. But on the interpretation under consideration, one would in effect be consuming millions of consecrated hosts insofar as each of the millions of particles that make up what common sense regards as a single host was being independently transubstantiated.

Perhaps such problems could be solved, though I am doubtful. Anyway, the issue illustrates the unexpected implications that philosophical assumptions can have for theology. (And thus the caution that any Catholic ought to exercise before embracing philosophical novelties. The Scholastics knew what they were doing.)

Published on October 09, 2019 19:51

September 30, 2019

Harvard talk (Updated)

This Friday, October 4, I will be giving a talk at Harvard University, sponsored by the Abigail Adams Institute. The topic will be “The Immateriality of the Mind.” The event will be in Sever Hall, Room 103, at 7:30 pm. You can RSVP here.

This Friday, October 4, I will be giving a talk at Harvard University, sponsored by the Abigail Adams Institute. The topic will be “The Immateriality of the Mind.” The event will be in Sever Hall, Room 103, at 7:30 pm. You can RSVP here.UPDATE 10/11: Some photos from the talk have been posted at Facebook.

Published on September 30, 2019 17:33

Harvard talk

This Friday, October 4, I will be giving a talk at Harvard University, sponsored by the Abigail Adams Institute. The topic will be “The Immateriality of the Mind.” The event will be in Sever Hall, Room 103, at 7:30 pm. You can RSVP here.

This Friday, October 4, I will be giving a talk at Harvard University, sponsored by the Abigail Adams Institute. The topic will be “The Immateriality of the Mind.” The event will be in Sever Hall, Room 103, at 7:30 pm. You can RSVP here.

Published on September 30, 2019 17:33

September 26, 2019

Aristotle’s Revenge and naïve color realism

The American Catholic Philosophical Association meeting in Minneapolis this November 21-24 will be devoted to the theme of the philosophy of nature. On the Saturday of the conference there will be an Author Meets Critics session on my book

Aristotle’s Revenge

. It will be chaired by Patrick Toner and the speakers will be Robert Koons, Stephen Barr, and myself.

The American Catholic Philosophical Association meeting in Minneapolis this November 21-24 will be devoted to the theme of the philosophy of nature. On the Saturday of the conference there will be an Author Meets Critics session on my book

Aristotle’s Revenge

. It will be chaired by Patrick Toner and the speakers will be Robert Koons, Stephen Barr, and myself.While we’re on the subject, I’d like to call your attention to a couple of very interesting responses to Aristotle’s Revenge, the first from Nigel Cundy at The Quantum Thomist and the second from Bonald at Throne and Altar. Both writers know the relevant science and both are open-minded and knowledgeable about the relevant philosophical ideas too. Both seem largely sympathetic to the book but also raise serious criticisms. They cover a lot of ground (since the book itself does) so there’s no way I can respond to everything they say in one post. So this will be the first in a series of occasional posts responding to their criticisms. The general project

Let me start with some general remarks about the project of the book. Its main thesis is that the fundamental notions of Aristotelian philosophy of nature – the reality of change, the theory of actuality and potentiality, hylemorphism, efficient causality, teleology, the intelligibility of nature – cannot be entirely eliminated from a coherent picture of physical reality. They are like J. L. Austin’s frog at the bottom of the beer mug, or the whack-a-mole that pops up somewhere else just when you thought you’d knocked it down. Even if you could banish them forever from this or that particular part of nature, you can never extirpate them from nature as a whole. Certainly modern science has not done so, and cannot do so. So I argue.

At the very least, I argue, they cannot be banished from any coherent conception of scientists themselves qua embodied subjects theorizing about the world and testing their theories via observation and experiment. You cannot make sense of how all that works – of what it is to be a conscious subject with a stream of thoughts and experiences, representing the world theoretically and manipulating scientific equipment, etc. – without implicitly supposing that change is real, that it involves the actualization of potential, that efficient and final causality are real, and so on. The scientist himself is, in effect, an impregnable fortress from which the Aristotelian cannot be pushed out. That is the fundamental way, though by no means the only way, that science presupposes Aristotelianism. And the reason it is not more widely noticed is the same reason why, as Orwell said, one does not notice what is right in front of one’s nose. The scientist looks out toward the world described by physics, and Aristotle is nowhere to be seen – but only because he is sitting right there next to him.

Furthermore, physics in any case captures abstract structure rather than concrete content, so that the absence of the key Aristotelian notions from its description of basic physical reality by itselftells us precisely nothing about whether the notions really correspond to anything in basic physical reality. Their absence reflects merely the methodologyof physics, not anything about the inner nature of the reality studied by means of that methodology. This epistemic structural realist account of physics is a second general theme of the book.

A third general theme is the poorly thought through nature of the purported mechanistic alternative to Aristotelianism. The mechanical world picture has always been more a rhetorical posture than a worked out alternative philosophy of nature. Where it claims to offer alternative explanations to those of the Aristotelian, in fact it merely pushes back questions to which an Aristotelian answer will ultimately still have to be given, or simply offers no explanation at all.

So, this is the “big picture” vision of the book. First, physics – and by extension the other sciences that take its account of the physical world for granted – couldn’t of their nature tell you one way or the other whether an Aristotelian philosophy of nature or a rival mechanistic position is true. Second, the mechanistic alternative isn’t coherently worked out anyway. And third, in any event there is no way in principle entirely to chuck out the basic Aristotelian notions. They will stubbornly remain forever ensconced within the fortress of the scientist himself qua embodied, thinking, conscious subject. These points, I argue, are unaffected by whatever we end up saying about the nature of time, space, and motion, whatever we say about reductionism in chemistry and biology, whatever we say about evolution, etc.

But the Aristotelian can in fact say much more about these details too, and that is the secondary thesis of the book. If “the big picture” is about defending the fortress, “the details” concern questions about how much territory can be reconquered by the Aristotelian in the various regions of the philosophy of time and space, the philosophy of matter, the philosophy of biology, and so on. And so I then go about developing lines of argument to show howterritory in these different areas might indeed be reconquered. For example, I defend an A-theory of time in general and presentism in particular, I argue against reductionism in chemistry and biology, propose an Aristotelian interpretation of evolution, and so forth.

Now, the main thesis or “big picture” of the book does not stand or fall with particular arguments having to do with the secondary theses concerning “the details” – with, say, what I argue concerning the presentist view of time, or my take on the metaphysics of evolution. One could reject what I say about one of these secondary issues while agreeing with what I say about other secondary issues, or one could even reject everything I say about these secondary issues while agreeing with my “big picture” thesis.

I emphasize all this because some readers are bound fallaciously to suppose that if they can refute what I say about one of these secondary matters, they will thereby have undermined the general Aristotelian philosophy of nature. Nope. It’s not that easy. If the Aristotelian has to fight on many fronts, so too does the anti-Aristotelian. And if my “big picture” thesis is correct, the anti-Aristotelian could win almost every battle and still lose the war.

Now, back to Cundy and Bonald. As far as I can tell, at least for the most part they don’t have a problem with what I am calling the “big picture” thesis, and even sympathize with it. Their objections have to do with what I am calling “the details,” and even then only some of those details. That is important context for what I will have to say in response.

Naïve color realism

In the remainder of this post I’ll focus on Bonald’s remarks about the physics and philosophy of color. I’ll turn in later posts to what Cundy and Bonald have to say about other issues, such as presentism. A standard reading of the revolution made by modern physics holds that it refuted our commonsense understanding of color (alongside other so-called “secondary qualities”). The idea is that what commonsense regards as redness, for example, exists only as a quale of conscious experience and that there is nothing in mind-independent reality that is really like that. What there is in mind-independent reality is instead merely a surface reflectance property that is causally correlated with the quale in question. We can redefine “redness” so that it refers to this property, but the commonsense notion of redness applies only to something subjective, something existing only in consciousness. And the same can be said for all other colors. Common sense is committed to the “naïve color realist” view that something like color as we experience it exists in mind-independent reality, even apart from our experience of it. But physics, it is claimed, has refuted this.

Endorsing arguments developed by contemporary philosophers like Hilary Putnam, Barry Stroud, and Keith Allen, I propose in Aristotle’s Revenge that something like naïve color realism can in fact still be defended. (See especially pp. 340-51.) And part of the background of the defense of this claim is the more general theme of the book that physics does not in any case give us an exhaustive description of matter, but captures only those aspects susceptible of mathematical description. Hence we should not be surprised if its description of matter fails to capture color as common sense understands it.

Now, in response to this, Bonald makes the following remarks:

[T]he claim that physics necessarily leaves out information about the physical world is a radical one.

It does nothing against Feser’s claim to point to the astounding reliability of physics, because physics could be perfectly reliable in its own order while completely ignoring features outside this order. However, if claims of the limitations of physics are to be more than gestures of epistemic humility, we must have some independent source of information. Feser sometimes thinks he can get this from our manifest image “common sense” experience/conceptualization of the world, but I find this questionable.

For example, in a section on secondary qualities, Feser rightly objects to claims that color is a mere subjective experience. Physics has clearly established that color is the wavelength of visible electromagnetic waves. But Feser dismisses this account of color as not being “color as common sense understands it”, so that the world of physics is still in some esoteric way colorless. I do not understand this at all. Common sense is not an understanding of light rival to that of optics; it’s not an understanding at all, but a bare experience of it. The qualia of colors (the only thing physics clearly does not provide) have no independent structure, which allows us to identify them simply as the experience of light at different wavelengths. The color of physics, meanwhile, explains all our experiences of color: the blueness of the sky, the order of colors in the rainbow, the red glow of a hot stove… What else is there?

End quote. Now, if I correctly understand Bonald’s criticism here, what he is saying is that it is a kind of category mistake to suppose that the qualia that physics leaves out of its story about color have anything to do with color as an objective feature of physical objects. Suppose we distinguish between RED (in caps) and red (in italics) as follows:

RED: the qualitative character or qualia of the color sensations had by a normal observer when he looks at fire engines, “Stop” signs, Superman’s cape, etc. (which is different from the qualitative character of the sensations had by e.g. a color blind observer)

red: whatever objective physical property it is in fire engines, “Stop” signs, Superman’s cape, etc. that causes normal observers to have RED sensations

What Bonald seems to be saying is that while physics tells us nothing about RED itself, it does tell us everything there is to know about red, including what it is about redobjects that makes them generate RED sensations in us. To be sure, physics tells us nothing about what it is about the brain that accounts for our sensations being RED, but that’s a different question – one for psychology, neuroscience, and philosophy of mind. In any event, it is (Bonald seems to think) a mistake to think that RED has anything to do with red. RED has to do with the mode in which the human mind perceivescolor, but red has to do with color itself as an objective feature of things. What we know about RED tells us no more about red than what we know about the structure of the eye or the optic nerve does. Like the eye or the optic nerve, RED is something in the perceiver, not something in the world the perceiver perceives. And something similar could be said about other colors.

A comment Bonald makes in response to a reader seems to me to confirm this interpretation of his position. And what he seems committed to is essentially Locke’s version of the distinction between primary and secondary qualities. To be sure, Bonald evidently rejects some versions of that distinction. But Locke’s way of putting it is to acknowledge that both primary and secondary qualities are really in physical objects themselves, but then to hold that whereas primary qualities produce in us sensations that resemble something in the objects, secondary qualities produce in us sensations that do not resemble anything in the objects. Hence, Locke would agree with common sense that physical objects really are red. But he would identify red with redand say that common sense is mistaken to hold that there is anything in physical objects that resembles RED. And that seems to be pretty much Bonald’s view (again, if I understand him correctly).

Now, if that is indeed what Bonald is saying, then what I would say in response is this. First, we need to distinguish two issues:

(1) Is there good reason to believe that physics does not in fact capture everything there is to red, and that common sense is (contra Locke) after all correct to suppose that there is in red something that resembles RED?

(2) Exactly what is the ontological relationship between this something-that-resembles-RED that is in red, and what physics tells us about red (e.g. surface reflectance properties)?

Now, in Aristotle’s Revenge, what I focus on is question (1). In particular, with Putnam, Stroud, Allen, et al., I set out some considerations that support an affirmative answer to that question. But I do not really have much to say there about question (2). Now, Bonald, as far as I can tell, does not really address what I have to say in support of an affirmative answer to (1). Rather, I think he is essentially expressing doubt that the naïve color realist could provide a good answer to (2), and is skeptical of naïve color realism for that reason. He doesn’t try directly to show that the arguments for the affirmative answer to (1) are wrong, but rather merely suggests that it is hard to see howthe affirmative answer could be true.

If this diagnosis is correct, then Bonald has not really answered the heart of my case for naïve color realism. But it is only fair to acknowledge that he nevertheless raises a very important question, and a difficult one. And question (2) is difficult precisely because our experience of color is indeed to a considerable degree contingent upon the nature and condition of the nervous system and the sense organs, and on the circumstances of observation. If the arguments I defend in the book are correct, that does not suffice to refute naïve color realism. But it does make it difficult to disentangle the aspect of RED that is objectively there in red itself and the aspect that is contributed by the mind.

But that brings me to the second point I want to make in response, which is that it is a mistake to suppose in the first place that we need to disentangle such aspects in order for RED to correspond to something in red. What I have in mind might be made clear by considering some parallel cases. I present these tentatively, and regard the analogies only as suggestive and not perfect.

First, consider the problem of universals. According to the Aristotelian realist approach to the problem, humanness exists as a universal only insofar as it is abstracted by the intellect from particular individual human beings. Outside the intellect, there is the humanness of Socrates, the humanness of Alcibiades, the humanness of Xanthippe, and so on, but not humanness as a universal divorced from these particulars. There is a sense, then, in which humannessqua universal depends on the mind, but not because it is the free creation of the mind. It is not. What the intellect abstracts is something that already really exists in the particular things themselves, but it exists there in an individualized way. It is only qua universal and thus qua abstracted from the individuals that it depends on the mind. So, a universal like humanness is both dependent on the intellect and grounded in mind-independent reality, and it is a mistake to think that it has to be the one to the exclusion of the other.

Now, in an analogous way, I would suggest, the something-that-resembles-RED that is in red can both be grounded in mind-independent reality and at the same time depend in part on the mind for its existence. It might really be there in red objects and be irreducible to what physics has to say about red, even if it is only actualized when a perceiver perceives it. (That is not to say that this something-that-resembles-RED that is in red is to be thought of as a universal. I’m not saying that naïve color realism is the same as the Aristotelian realist approach to universals, but merely drawing an analogy between the two.)

Here’s a second analogy. Thomists take transcendentals like being, truth, and goodness to be convertible with each other, the same thing looked at from different points of view. Hence truth is being qua intelligible, and goodness is being qua object of appetite. But that truth and goodness are to be characterized by reference to the intellect and appetite doesn’t make them the creations of intellect or appetite or imply that they don’t exist in a mind-independent way. Similarly, though the something-that-resembles-RED that is in redis to be characterized by reference to the mind that perceives it, it can still exist in a mind-independent way. (That is not to say that this something-that-resembles-RED that is in red is to be thought of as a transcendental. Again, I am simply drawing an analogy.)

Putnam sometimes liked to say that “the mind and the world together make up the mind and the world.” I certainly would not endorse everything Putnam associated with that slogan. But it is a colorful (as it were!) way of summing up the point that it is a mistake to think that every aspect of reality must be characterizable either in an entirely mind-dependent way or an entirely mind-independent way. Characterizing some aspects of reality might require reference both to the mind and to the mind-independent world, without the relevant components being separable into discrete mind-dependent and mind-independent chunks. Color would seem to be an example.

Here’s a final and different sort of consideration that might help clarify the relationship between what I am calling the something-that-resembles-RED that is in red, on the one hand, and what physics tells us about red on the other. The version of essentialism associated with contemporary analytic philosophers like Putnam and Saul Kripke tends to identify the essence of a thing with the hidden microstructure uncovered by science. But Aristotelian-Thomistic essentialists regard this as a mistake. The essence of a thing is not reducible to its microstructure, even if specifying the essence requires reference to the microstructure. (See e.g. David Oderberg’s discussion at pp. 12-18 of Real Essentialism .)

In light of this, we might say that what physics tells us about red is its microstructure, but that red isn’t reducible to that microstructure. There is in red, in addition to its microstructure, something-that-resembles-RED.

Published on September 26, 2019 19:13

September 20, 2019

Fastiggi on the revision to the Catechism

In the comments section under my recent Catholic World Report article “Three questions for Catholic opponents of capital punishment,” theologian Prof. Robert Fastiggi raises a number of objections. What follows is a reply. Fastiggi’s objections are in bold, and I respond to them one by one. Fastiggi begins:

In the comments section under my recent Catholic World Report article “Three questions for Catholic opponents of capital punishment,” theologian Prof. Robert Fastiggi raises a number of objections. What follows is a reply. Fastiggi’s objections are in bold, and I respond to them one by one. Fastiggi begins:There are multiple problems with Prof. Feser’s article.

1. He sets up a false dichotomy with his insistence that either Pope Francis’s revision of CCC 2267 represents a doctrinal change or merely a prudential judgment. This either/or does not do justice to the new formulation in the Catechism, which represents a deepening and a development of the moral principles of John Paul II that apply to the prudential order (but is not merely prudential in nature).

The revision to the Catechism asserts flatly that the death penalty should never be used. My claim is that there are only two ways to read this. Either the revision is saying that capital punishment should never be used even in principle, which would constitute a doctrinal change; or it is making a merely prudential judgment to the effect that it should never be used in practice. This is what Fastiggi characterizes as a false dichotomy.

Now, if I really were guilty of setting up a false dichotomy, then there should be some third alternative way of reading the revision that I have overlooked. So what is this third alternative? Tellingly, Fastiggi never tells us! He merely asserts that the revision “represents a deepening and a development of the moral principles of John Paul II” etc. But this is mere hand-waving unless we are told exactly what this deepened moral principle is that is neither (a) a reversal of past doctrine nor (b) a mere prudential judgment.

The reason he does not tell us what this third alternative is is that there could be no third alternative. Think about it. Any such alternative would have to say flatly that the death penalty is never permissible for reasons that are both stronger than merely prudential reasons (otherwise the purported third alternative would collapse back into alternative (b)), but not as strong as reasons of principle (or it would collapse back into alternative (a)). But that simply makes no sense. If the reasons why it is flatly impermissible are more than merely prudential, then there is nothing left for them to be than reasons of principle. And such reasons would inevitably entail a doctrinal change, since the Church has in the past consistently taught that capital punishment canin principle be used.

2. Feser falls into the fallacy of begging the question when he insists that a total rejection of the death penalty contradicts “the irreformable teaching of Scripture and Tradition.” This is his position, but I don’t believe he’s proven it to be true. There’s no irreformable teaching of Scripture and Tradition that prevents the Church from judging now that the death penalty is inadmissible in light of a deeper understanding of the Gospel.

This is an even less plausible charge than the claim that I had set up a false dichotomy. I would be guilty of begging the question if I simply asserted, without argument, that capital punishment is the irreformable teaching of scripture and tradition. But of course, I have in fact provided a great deal of argumentation in support of that claim, in writings such as my Catholic World Report article “Capital punishment and the infallibility of the ordinary Magisterium,” and in my book By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed (co-authored with Joe Bessette). And of course, Fastiggi knows this, both because he has commented before on these earlier works, and because I refer to them in the very article to which he is responding here!

Fastiggi has the right to disagree with the arguments I present in those writings, but he has no right to speak as if they don’t exist. Yet one would have to pretend that they don’t exist in order to accuse me of begging the question. Indeed, if I wanted to play Fastiggi’s game, I would say that he is begging the question, given that his comments here simply assume, without argument, that my other writings fail to make the case for irreformability.

Anyway, the interested reader is directed to the article and book just referred to, where he will find ample evidence that the Church has indeed taught irreformably that capital punishment is not per se contrary to either natural law or the Gospel.

But even if Feser were persuaded that his position is true, he should abide by what the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (CDF) teaches in its 1990 document, Donum Veritatis, no. 27: “ the theologian will not present his own opinions or divergent hypotheses as though they were non-arguable conclusions.”