Edward Feser's Blog, page 47

June 28, 2019

Frege on what mathematics isn’t

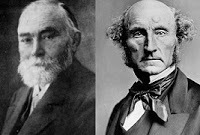

Mathematics is an iceberg on which the Titanic of modern empiricism founders. It is good now and then to remind ourselves why, and Gottlob Frege’s famous critique of John Stuart Mill in

The Foundations of Arithmetic

is a useful starting point. Whether Frege is entirely fair to Mill is a matter of debate. Still, the fallacies he attributes to Mill are often committed by others. For example, occasionally a student will suggest that the proposition that 2 + 2 = 4 is really just a generalization from our experience of finding four things present after we put one pair next to another – and that if somehow a fifth thing regularly appeared whenever we did so, then 2 and 2 would make 5. A comparable thesis from Mill that is criticized by Frege is the claim that the proposition that 1 + 2 = 3 is made true by our experience of finding that a group of objects that looks like OOO can be separated into two groups that look like O and OO. Frege jokes that in that case it is a good thing that all the objects in the world aren’t nailed down, otherwise we wouldn’t be able to separate them and thus it wouldn’t be true that 1 + 2 = 3. In fact, of course, 1 + 2 = 3 would still be true even in this scenario, in which case Mill’s account is wrong.

Mathematics is an iceberg on which the Titanic of modern empiricism founders. It is good now and then to remind ourselves why, and Gottlob Frege’s famous critique of John Stuart Mill in

The Foundations of Arithmetic

is a useful starting point. Whether Frege is entirely fair to Mill is a matter of debate. Still, the fallacies he attributes to Mill are often committed by others. For example, occasionally a student will suggest that the proposition that 2 + 2 = 4 is really just a generalization from our experience of finding four things present after we put one pair next to another – and that if somehow a fifth thing regularly appeared whenever we did so, then 2 and 2 would make 5. A comparable thesis from Mill that is criticized by Frege is the claim that the proposition that 1 + 2 = 3 is made true by our experience of finding that a group of objects that looks like OOO can be separated into two groups that look like O and OO. Frege jokes that in that case it is a good thing that all the objects in the world aren’t nailed down, otherwise we wouldn’t be able to separate them and thus it wouldn’t be true that 1 + 2 = 3. In fact, of course, 1 + 2 = 3 would still be true even in this scenario, in which case Mill’s account is wrong. Someone might accuse Frege of begging the question here, but he is not. Consider again my imagined student’s suggestion that if whenever we put two pairs of things together we regularly found that this left us with five things, we would judge that 2 + 2 = 5. A little reflection shows that this is not necessarily the case. For there are at least two ways we might describe such a scenario. We might, as the student proposes, characterize it as a world in which 2 + 2 = 5. But we might instead characterize it as a world in which 2 + 2 = 4 but where there is a strange causal law operating that ensures that bringing two pairs of things together to make a collection of four will immediately generate a fifth thing.

Now, which of these is the correct description of the student’s scenario? Experience itself cannot tell us, because any set of experiences is consistent with either description. I would say, and Frege would say, that we can know a priori that the first description is wrong, because the proposition that 2 + 2 = 5 is just nonsense. But put that aside for present purposes. What matters is the fact that we can make sense of the difference between these two alternative descriptions of the scenario despite the fact that experience cannot tell in favor of one rather than the other. And that entails that there is more to the content of the proposition that 2 + 2 = 4 than a mere description of what we happen to experience.

That, I submit, is Frege’s point. The proposition that 2 + 2 = 4 says more than merely that putting two pairs of things together will regularly give you four things, because we can describe a scenario in which it is still true that 2 + 2 = 4 even when putting two pairs of things together will regularly give you five things. That scenario would not by itself entail that 2 + 2 = 5, as opposed to merely entailing the operation of a weird causal law. And by the same token (and to return to Frege’s own example), the proposition that 1 + 2 = 3 says more than merely that a collection that looks like OOO can be separated into parts that look like O and OO, because we can describe a scenario in which no such separation is physically possible and yet it is still the case that 1 + 2 = 3. Mill’s account fails to capture even the meaning of the proposition that 1 + 2 = 3, let alone the grounds for judging it true.

A second and related problem with Mill’s view, notes Frege, is that it cannot account for examples that don’t involve collections of physical objects which we might know via sensory perception and separate into smaller parts. He gives the example of there being three methods of solving a certain equation. Methods of solving an equation are not physical objects that we might literally perceive to be lumped together as a collection, or which we might physically separate into parts (one part consisting of two of the methods, with the other part being the remaining method sitting off by itself).

A third problem is that Mill’s account is a non-starter when applied to facts concerning large numbers like 777,864. Obviously, it is absurd to suppose that our grasp of the proposition that 770,001 + 7,863 = 777,864 is grounded in experience of finding that whenever groups of 770,001 things are lumped together with groups of 7,863 things, we find that the resulting collection has 777,864 things in it.

Mill says several other things which Frege shows cannot be right. For example, there is the claim that number is merely a property that a bundle of things has, alongside its color, shape, or the like. Hence a pile of ten red pens can be said to be ten, just as it can be said to be red. As Frege would ask, why say that the pile has the property of being ten, as opposed to being twenty (on the grounds that if we distinguish the pens from their pen caps, we get twenty things)? Or why not say that it has the property of being in the billions (on the grounds that we get such a number when we distinguish the particles out of which the pens are composed)?

Furthermore, Frege points out, 1,000 grains of wheat remain 1,000 grains even after they are sown far and wide and no longer form a bundle. Nor would Mill’s account explain what the number 0 is, since it obviously can’t be a property that a pile of pens or a bundle of grains of wheat has, the way Mill thinks being ten and being a thousand are properties of such collections. And then there is the fact that we can apply number to things that are not physical objects that might be lumped together into a bundle (for example, the number of ways to prove a theorem, the number of concepts one entertained Wednesday morning, or the number of events occurring right now).

Mill also says that even 1 = 1 can be false, insofar as one one-pound weight does not always weigh exactly the same as another. This is like the fallacy committed by the student who thinks that 2 + 2 = 4 is merely a generalization of the observation that when we put pairs of things together we typically find that the result is a collection of four things. As Frege says, it simply gets wrong what a claim like 1 = 1 is asserting. It isn’t an empirical claim to the effect that, as a matter of contingent fact, any item that we happen to characterize as weighing one pound will always be exactly equal in weight to any other item we happen to characterize as weighing one pound. One reason why this is a mistake is, of course, that typically we are only approximating when we characterize something as weighing a pound. But the deeper point is that, even if we were not speaking merely approximately, the claim would not be a mere description of the empirical facts. If it turned out that no two things were ever exactly of the same weight, that would not entail that it is false that 1 = 1. It would entail only that this arithmetical truth does not strictly describe anything in the empirical world.

As Frege says, Mill’s error is to suppose that arithmetical claims are inductive generalizations from particular cases, and to confuse what are in fact applications of arithmetical truths with empirical evidence for those truths. When we stick one pair of apples next to another to yield four apples, we are not assembling one further bit of empirical evidence in a way that gives additional inductive support for a contingent general claim to the effect that 2 + 2 = 4. Rather, we are applying a necessary truth, and one that is already known a priori, to a specific case. And the same thing is true of our application of the proposition that 1 = 1 to the comparison of two weights and the like.

Again, it would be a mistake to accuse Frege of begging the question against Mill. He isn’t stomping his foot and refusing to listen to empirical evidence against a contingent generalization to the effect that 1 = 1. Indeed, it would beg the question against Frege to characterize the situation that way, because his point is precisely that the proposition that 1 = 1 is not a contingent empirical generalization in the first place. His point is that when Mill characterizes arithmetical statements that way, he is changing the subject. He is no longer talking about the proposition usually expressed by “1 = 1,” but rather about some empiricist-friendly ersatz. Mill is really just ignoringthe arithmetical truth that 1 = 1 and talking instead about a very different sort of claim while using the same symbols.

The actual situation, for Frege, is that it is only because we already have an independent grasp of the meaning and truth of arithmetical propositions that we know how to apply them to concrete empirical cases. Frege gives the example of pouring 2 unit volumes of liquid into 5 unit volumes of liquid. We judge that this will yield 7 unit volumes of liquid only given the absence of some chemical reaction or other causal factor that might alter the volume. We don’t “work up” from the specific empirical cases to the general arithmetical proposition but rather “work down” from the arithmetical proposition to a description of what is really going on in the specific empirical cases.

Published on June 28, 2019 10:17

June 25, 2019

Just say the damn sentence already

Suppose you are a Catholic who thinks the death penalty ought never to be applied in practice under modern circumstances. Fine. You’re within your rights. Whatever one thinks of the arguments for that position, it is certainly orthodox. However, that position is very different from saying that capital punishment is always and intrinsically wrong, wrong per se or of its very nature. That position is not orthodox. It is manifestly contrary to scripture, the Fathers and Doctors of the Church, and the consistent teaching of the popes up until at least Benedict XVI. The evidence for this claim is overwhelming, and I have set it out in many places – for example, in this article and in this book co-written with Joe Bessette. Attempts to refute our work have invariably boiled down to ad hominem attacks, red herrings, question-begging assertions, special pleading, straw man fallacies, or other sophistries and time-wasters. So, every Catholic is obliged to affirm, on pain of heterodoxy, the following sentence, which for ease of reference I will label

Suppose you are a Catholic who thinks the death penalty ought never to be applied in practice under modern circumstances. Fine. You’re within your rights. Whatever one thinks of the arguments for that position, it is certainly orthodox. However, that position is very different from saying that capital punishment is always and intrinsically wrong, wrong per se or of its very nature. That position is not orthodox. It is manifestly contrary to scripture, the Fathers and Doctors of the Church, and the consistent teaching of the popes up until at least Benedict XVI. The evidence for this claim is overwhelming, and I have set it out in many places – for example, in this article and in this book co-written with Joe Bessette. Attempts to refute our work have invariably boiled down to ad hominem attacks, red herrings, question-begging assertions, special pleading, straw man fallacies, or other sophistries and time-wasters. So, every Catholic is obliged to affirm, on pain of heterodoxy, the following sentence, which for ease of reference I will labelThe Sentence: “Capital punishment is not always and intrinsically wrong.”

If a Catholic wants to add to this sentence – for example by saying “Capital punishment is not always and intrinsically wrong; however, it is better never to use it, for such-and-such reasons” – then, again, that’s fine. But a Catholic who dissents from the proposition conveyed by The Sentence is guilty of heterodoxy, and a prelate who refuses to affirm The Sentence is guilty of failing to uphold orthodoxy – and of course, it is the job of prelates to uphold orthodoxy.

Curiously, though, with a few honorable exceptions, few contemporary prelates seem willing to affirm it. Many keep silent. Many speak ambiguously, or even say things that seem to contradict The Sentence. The latest example is Cardinal Timothy Dolan, who in a recent tweet declared that in light of Pope Francis’s recent revision to the Catechism, “there now exists no loophole to morally justify capital punishment.” (In response, one wag in Dolan’s Twitter feed said he was“looking forward to the USCCB publishing the CCC in the new loose-leaf edition.” Canon lawyer Edward Peters has also criticized Dolan’s tweet.) In an earlier article, the cardinal said that a “consistent” Catholic has to be against both the death penalty and abortion, and that it was “hypocrisy” not to be against both.

All of that certainly makes it sound as if Cardinal Dolan thinks that capital punishment is, like abortion, intrinsically wrong – that to execute even a guilty human being is morally on a par with aborting an innocent human being. And that would contradict the clear and consistent tradition of the Church, which distinguishes between the innocent and the guilty. This (rather obvious) distinction is the reason why the Church has for two millennia seen no inconsistency or hypocrisy at all in opposing abortion while permitting capital punishment, any more than there is any inconsistency or hypocrisy in opposing kidnapping while approving of the arrest and incarceration of the guilty.

However, in the same article, Dolan says:

The decision of Pope Francis was not a change in Church teaching, but a development. No Pope can contradict previous Church teaching. He can modify, clarify, strengthen, reaffirm, and expand. That’s development, not alteration. The Pope is the servant, not the master, of God’s revealed Word as preserved and passed on by His Church.

End quote. Now, as the Dominican theologian Fr. Brian Mullady emphasizes in a recent article, a true developmentof doctrine cannot reverse past doctrine. If you say “All men are mortal and Socrates is a man,” and I come along later and conclude from what you said that Socrates is mortal, that would be a development, clarification, or expansion of your claims – a drawing out from them of their implications. But if instead I said that Socrates is not mortal, I would not be “developing” or “clarifying” or “expanding” your claims at all, but manifestly contradicting them.

Similarly, if Cardinal Dolan were to reject The Sentence, he would not be developing or clarifying or expanding on traditional teaching at all, but manifestly contradicting it. So, if the cardinal really is serious about affirming only developments of past doctrine and never contradictions of it, then he will have to agree that capital punishment – unlike abortion – is not intrinsically immoral, in which case there can be at least some instances in which it is morally justifiable.

So, Cardinal Dolan’s statements are ambiguous. If he were simply to affirm The Sentence, even with a vigorous “However…” annexed to it, the ambiguity would at once be removed. Strangely, he does not do so.

Discussing the U.S. bishops’ proposed alteration to the language of their catechism for adults so as to bring it into conformity with Pope Francis’s revision, Bishop Robert Barron recently said that there is an “eloquent ambiguity” in the pope’s revision insofar as it “doesn’t use the language of intrinsic evil” but also “uses language like… inadmissible, morally unacceptable, etc.” The U.S. bishops’ alteration, we are told, will also avoid speaking of intrinsic evil. However, it seems that neither Bishop Barron nor the U.S. bishops acting collectively in their proposed alteration will utter The Sentence either.

Why not? After all, they don’t explicitly reject The Sentence. On the contrary, like Cardinal Dolan, Bishop Barron and the U.S. bishops’ proposed alteration insist on “continuity” with past Catholic teaching, even if they leave it unexplained exactly how the new language is continuous with past teaching.

Moreover, the whole point of a catechism is to clarifywhat the Church teaches, whereas ambiguity (“eloquent” or otherwise) entails a lack of clarity about what the Church teaches. Indeed, the whole point of having bishops, and indeed of having a pope, is for them to clarify to the faithful what the Church teaches, not to be eloquently ambiguous about it. For catechisms and bishops to speak ambiguously rather than clearly is, accordingly, simply for them to be derelict in their duty.

Then there is the fact that, as the bishops well know, many Catholics are concerned that the pope’s revision to the catechism marks an implicit rupture with past teaching, and thus threatens to falsify the Church’s claim to preserve the deposit of faith undiluted. Some are having their faith shaken, or even leaving the Church. All the evasion and double talk is undermining their confidence, not reinforcing it. There is an extremely easy way for the bishops to help fortify these doubting Catholics, which it is their sacred duty to do. Here it is: Simply utter The Sentence. They can still go on to add whatever qualifiying “However…” they like and passionately oppose capital punishment in practice.

Nor do they lack the authority to utter The Sentence. Like the pope, they are successors to the Apostles with authority to teach the deposit of faith, and they need no special authorization from the pope simply to reiterate what has always and everywhere been taught. Nor would they be contradicting the pope, since he has not explicitly denied The Sentence himself. So why won’t they do it?

Just say the damn sentence already. Like this: “Capital punishment is not always and intrinsically wrong.” See how easy it is?

Published on June 25, 2019 09:49

June 19, 2019

Links for thinkers

David Oderberg’s article “Death, Unity, and the Brain” appears in Theoretical Medicine and Bioethics.

David Oderberg’s article “Death, Unity, and the Brain” appears in Theoretical Medicine and Bioethics.Nicholas Maxwell at Aeon calls for a revival natural philosophy. Gee, maybe someone ought to write a book on the subject.

Philosopher Kathleen Stock on gender dysphoria and the reality of sex differences, at Quillette. At Medium, philosopher Sophie Allen asks: If transwomen are women, what is a woman?

The Onion on liberal self-satisfaction . At National Review, Tucker Carlson on America’s cultural decline. At First Things, Chris Arnade on back row America. Arnade’s book Dignity is reviewed at The Week , The University Bookman , Counterpunch , and The Federalist .

At 3:16, Richard Marshall interviews philosopher and Aristotle scholar Christopher Shields. What Is It Like to Be a Philosopher? interviews historian of philosophy Peter Adamson.

At Areo, Darel Paul on the anti-intellectual religious fanaticism of the “Great Awokening” now plaguing some college campuses.

At Aeon, Adam Frank, Marcelo Gleiser, and Evan Thompson on science’s blind spot .

John Skalko’s Disordered Actions: A Moral Analysis of Lying and Homosexual Activity is now out from Editiones Scholasticae. Walter Farrell’s The Natural Law According to Aquinas and Suárez has just been reprinted by Cluny Media.

At the Washington Examiner, Suzanne Venker argues that feminism has harmed millennials. At Metro, political scientist Eric Kaufmann predicts a return to sex as procreation rather than recreation.

At Quillette, neuroscientist Larry Cahill on the differences between male and female brains. Cahill is interviewed at Medium.

Kenneth Francis on the vicissitudes of grammar, at New English Review.

At Scientific American, physicist Marcelo Gleiser says that atheism is inconsistent with scientific method.

Confused by the messy continuity of the X-Menseries of movies? The Wrap sorts it all out for you. Kyle Smith at National Review defends the underrated Iron Man 2.

The Chronicle Review interviews economist Glenn Loury about affirmative, politics, and academia.

Kathrin Koslicki’s Form, Matter, Substance is reviewed at Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews. Also reviewed is Rani Lill Anjum and Stephen Mumford’s What Tends to Be: The Philosophy of Dispositional Modality.

Political scientist Kristian Niemietz on the endless self-delusion of socialists, at Quillette. National Review reports on Sotheby’s auction of F. A. Hayek’s personal effects.

Speaking of Quillette: The Chronicle of Higher Education reports that the thought police are not fans.

At Claremont Review of Books, Robert Royal asks: Is the pope Catholic? Diane Montagna at LifeSite reports on the pope’s latest remarks about capital punishment.

Dissent on “Jewish conservative and Yiddish radical” Daniel Bell. The New Republic on Nathan Glazer.

At SyFy, an oral history of Marvel’s Secret Wars. At Voyage, Julian Sicam on Aquinas and the popularity of superheroes.

John Schwenkler at Commonweal looks back at G. E. M. Anscombe. Anil Gomes at The Philosophers’ Magazine looks back at P. F. Strawson.

Catholic theologian Matthew Levering is interviewed at Crux.

The Spectator on how Einstein was baffled by his own popularity. Aeon on Henri Bergson’s one-time popularity and the backlash against it.

At The Daily Mirror, Larry Harnisch laments that there are no good books about the Black Dahlia murder. Harnisch has long been the go-to guy for debunking nonsense written on the subject.

Published on June 19, 2019 11:55

June 15, 2019

The bishops and capital punishment

A group of five prelates comprising Cardinal Raymond Burke, Bishop Athanasius Schneider, Cardinal Janis Pujats, Archbishop Tomash Peta, and Archbishop Jan Pawel Lenga this week issued a “Declaration of the truths relating to some of the most common errors in the life of the Church of our time.” Among the many perennial Catholic doctrines that are now commonly challenged but are reaffirmed in the document is the following:

A group of five prelates comprising Cardinal Raymond Burke, Bishop Athanasius Schneider, Cardinal Janis Pujats, Archbishop Tomash Peta, and Archbishop Jan Pawel Lenga this week issued a “Declaration of the truths relating to some of the most common errors in the life of the Church of our time.” Among the many perennial Catholic doctrines that are now commonly challenged but are reaffirmed in the document is the following:In accordance with Holy Scripture and the constant tradition of the ordinary and universal Magisterium, the Church did not err in teaching that the civil power may lawfully exercise capital punishment on malefactors where this is truly necessary to preserve the existence or just order of societies (see Gen 9:6; John 19:11; Rom 13:1-7; Innocent III, Professio fidei Waldensibus praescripta; Roman Catechism of the Council of Trent, p. III, 5, n. 4; Pius XII, Address to Catholic jurists on December 5, 1954). No doubt the prelates judged this passage necessary because of the controversy generated by Pope Francis’s revision last year to the Catechism’s treatment of capital punishment – the wording of which is at best ambiguous, and at worst insinuates that capital punishment is always and intrinsically evil. (I have discussed the problems with the revision in articles at First Things and Catholic Herald . Last year a group of concerned Catholic scholars and clergy appealed to the cardinals of the Church to ask the pope to retract the revision.)

Crux reports that , in a very different move, a committee headed by Bishop Robert Barron is considering altering the language of the U.S. bishops’ catechism for adults so as to bring it into conformity with Pope Francis’s revision. Now, Crux also noted that:

Barron said June 11 that the draft emphasizes the dignity of all people and the misapplication of capital punishment. Discussion of the proposed revision is not meant to be a debate on the death penalty overall, he added…

Barron reiterated that the bishops are not debating the change to the universal catechism itself or even the overall issue of capital punishment, but simply deciding if the added revision to the adult catechism adequately reflects recent catechism revisions.

End quote. These remarks from Bishop Barron indicate that the U.S. bishops are not going to address the controversy over how to interpret Pope Francis’s revision, or even the “overall” issue of capital punishment as opposed to merely its “misapplication.” The Cruxarticle also adds that the alteration being considered by the U.S. bishops “emphasizes the continuity of Catholic teaching on this topic by citing St. John Paul II’s encyclical, ‘The Gospel of Life,’ and previous statements of U.S. bishops.”

Evidently, then, the bishops are not going to be adding language that explicitly asserts that capital punishment is intrinsically wrong. That is good to know. However, it is not clear that the language they will be adding will explicitly deny that capital punishment is intrinsically wrong. But such an explicit denial is necessary if the bishops want to “emphasize the continuity of Catholic teaching on this topic.” Merely citing Pope John Paul II or previous U.S. bishops’ statements will in no way establish continuity unlessthe quotes in question include explicit affirmations from the late pope or the bishops to the effect that capital punishment can sometimes be legitimate at least in principle.

Nor is citing statements from recent years a very impressive way of establishing “continuity” in the first place. After all, the reason the bishops see a need to emphasize continuity is surely that many people worry that current teaching involves a rupture with scripture and two millennia of previous magisterial teaching. So, what is needed is a statement clearly explaining how current teaching is in continuity not only with Pope St. John Paul II and earlier U.S. bishops, but also with the teaching of scripture, the Fathers of the Church, popes like St. Innocent I, Innocent III, St. Pius V, St. Pius X, and Pius XII, and Doctors of the Church like St. Augustine, St. Thomas Aquinas, St. Robert Bellarmine, and St. Alphonsus Liguori – all of whom taught that capital punishment can be legitimate in principle, even if they did not all favor resorting to it in practice.

Now, some other bishops have in recent years reaffirmed the Church’s traditional teaching. The most famous example is the 2004 statement from Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (then the Church’s chief doctrinal officer, who would go on to become Pope Benedict XVI) to the effect that:

If a Catholic were to be at odds with the Holy Father on the application of capital punishment… he would not for that reason be considered unworthy to present himself to receive Holy Communion. While the Church exhorts civil authorities… to exercise discretion and mercy in imposing punishment on criminals, it may still be permissible… to have recourse to capital punishment. There may be a legitimate diversity of opinion even among Catholics about… the death penalty.

End quote. This passage was repeated almost verbatim in a 2004 USCCB document on Catholics in public life written by Archbishop William Levada. The following year, Bishop Fabian Bruskewitz affirmed that capital punishment is not intrinsically evil, and that “one can disagree with the bishops’ teaching about the death penalty and still present himself for holy Communion… and our Holy Father, as Cardinal Ratzinger, made that clear.” Archbishop Charles Chaput, despite his personal opposition to capital punishment, also stated in 2005 that:

The death penalty is not intrinsically evil. Both Scripture and long Christian tradition acknowledge the legitimacy of capital punishment under certain circumstances. The Church cannot repudiate that without repudiating her own identity.

Now, will the revision currently being considered by the U.S. bishops “emphasize continuity” with these statements of just fifteen or so years ago? Do the bishops still teach that the death penalty is not intrinsically wrong? Do they teach that the question of whether to apply capital punishment is, accordingly, a prudential matter about which Catholics can legitimately disagree (as Ratzinger, Levada, and Bruskewitz all affirmed)? Do the U.S. bishops agree with the statement on capital punishment put forward by cardinals Burke and Pujats and bishops Schneider, Peta, and Lenga? And if they would answer any of these questions in the negative, how can their current teaching be in “continuity” with past Catholic teaching? What kind of “continuity” is it that would countenance a reversal of what was taught only fifteen years ago, let alone for over two millennia?

Crux says that the U.S. bishops are concerned to address “what the U.S. Church teaches its adult members about the death penalty.” What the U.S. Church teaches will not be clear unless questions like these are answered straightforwardly.

Published on June 15, 2019 10:39

June 11, 2019

Augustine on capital punishment

In his book

On Augustine: The Two Cities

, Alan Ryan says that Augustine’s “understanding of the purpose of punishment made the death penalty simply wrong” (p. 82). That is a bit of an overstatement. In The City of God, Augustine writes:

In his book

On Augustine: The Two Cities

, Alan Ryan says that Augustine’s “understanding of the purpose of punishment made the death penalty simply wrong” (p. 82). That is a bit of an overstatement. In The City of God, Augustine writes:However, there are some exceptions made by the divine authority to its own law, that men may not be put to death. These exceptions are of two kinds, being justified either by a general law, or by a special commission granted for a time to some individual. And in this latter case, he to whom authority is delegated, and who is but the sword in the hand of him who uses it, is not himself responsible for the death he deals. And, accordingly, they who have waged war in obedience to the divine command, or in conformity with His laws, have represented in their persons the public justice or the wisdom of government, and in this capacity have put to death wicked men; such persons have by no means violated the commandment, “You shall not kill.” (Book I, Chapter 21) And in On the Sermon on the Mount, Augustine says:

But great and holy men… punished some sins with death, both because the living were struck with a salutary fear, and because it was not death itself that would injure those who were being punished with death, but sin, which might be increased if they continued to live. They did not judge rashly on whom God had bestowed such a power of judging. Hence it is that Elijah inflicted death on many, both with his own hand and by calling down fire from heaven; as was done also without rashness by many other great and godlike men, in the same spirit of concern for the good of humanity. (Book I, Chapter 20)

Clearly, then, Augustine did not regard the death penalty as “simply wrong.” However, it is true that he tended to oppose its use in practice, and often pleaded for clemency in particular cases. For example, in one letter he urges a proconsul “to forget that you have the power of capital punishment,” and in another he says that “our desire is rather that justice be satisfied without the taking of their lives.” (See the footnotes on p. 115 of By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed for references to other passages from Augustine either upholding the legitimacy of capital punishment in theory or recommending against its use in practice.)

Ryan’s discussion of Augustine’s rationale is instructive. The saint’s reluctance to apply the death penalty had nothing to do with squeamishness about punishment, violence, or coercion. As Ryan notes, Augustine’s just war theory allows that a just cause for war could include not only self-defense, but also the aim of punishing a state that is guilty of crimes. Augustine was also not opposed to state suppression of heresy. As Ryan notes:

Augustine took it for granted that being coerced into receiving the truth was a benefit, not a burden; it was a view one might expect from a man who thought that corporal punishment might be administered lovingly and with the intention to bring the offender to his senses. (p. 95)

Nor did utopian politics underlie Augustine’s opposition to capital punishment. Ryan has much to say about Augustine’s doubt that true justice – as opposed to a mere absence of excessive disorder – can ever be realized in the earthly city, given original sin. Augustine did not even favor overthrowing tyrants, let alone ambitious schemes for social improvement.

In general, Augustine’s opposition to the actual practice of capital punishment was, Ryan says, “not the expression of a modern humanitarian impulse” (p. 84). He elaborates as follows:

Augustine did not flinch from physical suffering… He did not flinch from the fact of the hangman or the soldier or the civilian police. It no doubt took a peculiar temperament to earn a living by butchering one’s fellow human beings, but it did not follow that the hangman was not God's instrument. In this vale of sorrows, he is. Nor should we, looking back from a safe distance, ignore the fact that corporal and capital punishments are almost inescapable in societies where the expense of housing and feeding prisoners would be intolerable, and where only the better-off would have had the resources to pay fines – as they frequently did. The violent poor would suffer violence at the hands of the state, as would poor robbers and housebreakers. Augustine's fear was not that they would suffer but that they would suffer for what they had not done. (pp. 84-85)

That brings us to Augustine’s actual concerns, which were twofold, and had largely to do with the brutality of the methods deployed in the Roman system of criminal justice. The accused were often tortured until an interrogator was satisfied that he had gotten an honest answer. One of Augustine’s worries, writes Ryan, was that an innocent person might either die from the torture itself, or falsely confess to a crime so as to escape further torture and then be unjustly executed. The other main worry was that “the criminal is supposed to be brought to a state of repentance,” yet “the barbarity of Roman executions” made it “almost impossible for him to die in a good frame of mind” (p. 83).

So, Augustine worried, first, that an innocent person might be killed, and second, that a guilty person might not have a chance to repent of his sins before death. But notice how historically contingent are the specific reasons why Augustine (on Ryan’s interpretation) thought the death penalty entailed these dangers. Torture and barbaric methods of execution were the main sources of the problem. It is because a person might give a false confession under torture that the innocent might be executed, and it is because of the terror and physical pain of extreme methods of execution that the guilty would be unable to focus on getting themselves right with God.

Aquinas, when considering the suggestion that execution removes the possibility of repentance, responds that the objection is “frivolous” and that if an evildoer would not repent even in the face of imminent death, he probably would never repent (Summa Contra Gentiles III.146). It might seem that this reflects a disagreement with Augustine, but the considerations raised by Ryan show that that is not necessarily the case. Augustine was writing when Europe was still largely pagan, whereas Aquinas was writing long after Christianity had taken deep root. Perhaps Aquinas would agree that if capital punishment were inflicted in the specific way that it was in Augustine’s time, then there would be a problem. That is compatible with the view that if it is administered in a more civilized way, then it would not interfere with repentance and might even encourage it.

In any event, the specific reasons why (according to Ryan’s interpretation) Augustine opposed the use of capital punishment would not apply in a Western context in modern times. For DNA evidence has made it possible to be close to certain of guilt in at least many cases, modern methods of execution are now close to being as antiseptic and painless as possible, and modern Western criminal justice does not sanction torture as a method of gathering evidence. (I’m not talking about anti-terrorism practices post-9/11 – that is a different topic that I’m not addressing here – but rather everyday criminal investigations.)

Contemporary Christian opponents of capital punishment sometimes emphasize that their position is simply a return to that of the Fathers of the Church. But the moral, political, and theological premises on which they base their opposition are often very different from those of a Father like Augustine. The critics also often argue that past Christian support for capital punishment reflects historical and cultural circumstances that no longer hold. But as the example of Augustine shows, past Christian opposition to capital punishment can also reflect historical and cultural circumstances that no longer hold.

Published on June 11, 2019 22:50

June 7, 2019

A clarification on integralism

Talk of integralism is all the rage in recent weeks, given the dispute between David French and Sohrab Ahmari and Matthew Continetti’s analysis of the state of contemporary conservatism, on which I commented in a recent post. What is integralism? Rod Dreher quotesthe following definition from the blog

The Josias

:

Talk of integralism is all the rage in recent weeks, given the dispute between David French and Sohrab Ahmari and Matthew Continetti’s analysis of the state of contemporary conservatism, on which I commented in a recent post. What is integralism? Rod Dreher quotesthe following definition from the blog

The Josias

:Catholic Integralism is a tradition of thought that rejects the liberal separation of politics from concern with the end of human life, holding that political rule must order man to his final goal. Since, however, man has both a temporal and an eternal end, integralism holds that there are two powers that rule him: a temporal power and a spiritual power. And since man’s temporal end is subordinated to his eternal end the temporal power must be subordinated to the spiritual power. End quote. Now, I wouldn’t say that this definition is wrong, but it does need qualification. In particular, where talk of “the end of human life” and related terms are concerned, we need to draw some distinctions – distinctions that are usually ignored in modern discussion of these issues, and the neglect of which leads to serious misunderstandings, certainly where the topic of Catholic integralism is concerned.

What I am talking about are the distinctions between a natural end and a supernatural end, and between natural theologyand revealed theology. A natural end of a human being is an end toward which we are aimed or directed by nature, just by virtue of being human beings or rational animals. For example, by virtue of being a kind of animal, we are naturally aimed or directed toward the realization of ends like acquiring food and shelter. And by virtue of being rational, we are naturally directed toward the realization of ends like the attainment of truth.

A supernatural end is one toward which our nature itself does not direct us, even if it is not inconsistent with our nature. It is one that is above what our nature would by itself allow us to realize (hence supernatural), so that realizing it requires special divine assistance. The beatific vision – the direct or unmediated knowledge of God’s nature enjoyed by the blessed in heaven – is our supernatural end, impossible to achieve without grace. (Note that “supernatural” in this sense has nothing to do with ghosts, goblins, and the other usual strawmen.)

Natural theology has to do with knowledge about God’s existence and nature that is possible for us to acquire simply by virtue of applying our natural powers of reasoning, via purely philosophical arguments. It requires no appeal to special divine revelation – to scripture, the tradition of the Church, the teachings of a prophet, or the like. It is the kind of knowledge that pagan philosophers like Aristotle and Plotinus had, even if their views were mixed with various errors. Revealed theology, by contrast, is knowledge of God’s nature and will of the kind that is available only through some special divine revelation (and thus through scripture, etc.). The doctrine of the Trinity is a standard example. And knowing that it is possible for us by grace to attain the beatific vision would be another example.

Now, since there is such a thing as natural theology, acquiring knowledge of God’s existence and nature through the use of pure reason is also among our natural ends. Indeed, for pagans like Aristotle and Plotinus, no less than for Christians, it is the highest of our natural ends. And it entails that the highest of our natural obligations – what we most need to pursue in order to flourish as human beings – is, in Aristotle’s words, “the contemplation and service of God.”

This is not the same as the beatific vision, because it involves merely mediated or inferential knowledge of God, rather than the intimacy of a direct knowledge of the divine nature. Unlike the beatific vision, such mediated knowledge is possible for us by nature rather than only by grace. And there is much else that we can know by nature or via purely philosophical arguments, such as the immortality of the soul and the natural law conception of ethics – with everything that entails about abortion, sexual morality, and the general obligation on the part of both individuals and societies to recognize and honor God.

The relevance to Catholic integralism is this. Many people seem to think that the debate over integralism is a debate over whether religion, in general, ought to have an influence in politics, and it seems to me that the definition provided by The Josias might reinforce this impression. Many people also seem to think that Vatican II’s teaching on religious liberty abandoned the idea that religion should have any influence on politics. But all of that is incorrect. From the natural law point of view, and from the point of view of both traditional and post-Vatican II Catholic social doctrine, there is no question that naturaltheology and natural law must inform politics, whatever one says about specifically Catholic theology.

That means that even a non-integralist Catholic could and should hold that at least a generic theism should be affirmed by the state and that government policy should be consistent with the principles of natural law. For these are matters of philosophy, not divine revelation. They can all be established by rational arguments that make no reference to scripture or the magisterium of the Church. You could be a purely philosophical theist – a Neoplatonist, say, or an Aristotelian, or a Leibnizian – who completely rejects the very idea of divine revelation, and still hold that the state ought to honor God, that abortion should be outlawed, and so on. The atheist state is contra naturam, not merely contrary to divine revelation.

It might be objected that arguments for these theses, even if purely philosophical, are obviously controversial, so that no such theses should influence public policy. But though the premise is true, the argument is a non sequitur. Every substantive claim about morality and politics is controversial, including those to which liberals are committed. Liberals had no qualms about pushing for same-sex marriage even when it was far more controversial than it is now. They had no qualms about imposing the legalization of abortion on the entire country by judicial fiat when the idea was highly controversial, as it still is. So they cannot consistently hold that philosophical views about natural theology and natural law ethics should not influence public policy, on the grounds that those views are controversial.

(Liberalism claims to be “neutral” or impartial between competing controversial philosophical, moral, and religious views in a way that other political philosophies are not, but as I have argued in several places, this purported neutrality is completely bogus and delusional. See e.g. my essay “Self-Ownership, Libertarianism, and Impartiality,” in Neo-Scholastic Essays .)

Rightly understood, the debate over Catholic integralism has to do with whether specifically Catholic doctrines, which concern our supernatural end and are matters of revealed theology, should have an influence on public policy. The state should favor theism, but must it favor the Church? That is the sort of question that the debate over how to interpret Vatican II’s teaching on religious liberty has always been about. No one can justify a complete separation of religion and politics on the basis of Vatican II. The most one could argue for (whether correctly or incorrectly) is that Vatican II abandoned the ideal of a specifically Catholic state.

There are two basic schools of thought on the latter question. On one view, Vatican II reversed the teaching of the pre-Vatican II popes and rejected even in principle the idea that the state should favor the Church. Call this the “hermeneutics of rupture” interpretation. Some people who adopt this interpretation approve of the purported rupture in teaching (i.e., progressives and some neo-conservative Catholics), while others deplore it (i.e., some traditionalist Catholics, who argue that the teaching of Vatican II was not infallible anyway and thus can and ought to be reversed in the future).

On another view, Vatican II did not reverse past teaching, but merely made a prudential judgment to the effect that, though the Church retains the right in principle to be favored by the state, it is no longer fitting for her to exercise this right. Furthermore, on this interpretation, Vatican II’s reference to an individual right to religious liberty can be interpreted in a way consistent with the Church being favored by the state. Call this the “hermeneutics of continuity” interpretation. Some who adopt this interpretation think that the prudential judgment in question was sound (i.e., many conservatives and probably at least some traditionalist Catholics), while others think it was unwise (i.e., those traditionalist Catholics who don’t accuse Vatican II of doctrinal error but think the state should, where possible, continue to favor the Church).

Catholic integralists are essentially those who think that, however we interpret Vatican II, it is irreformable Catholic teaching that the ideal situation is for the state to favor the Church. But integralists in this sense nevertheless can and do disagree over the practical implications of this position. What we might call soft integralism is the view that, though in theory the state may and ideally should favor the Church, in practicethis is extremely unlikely ever to work out very well. Politics and culture, on this view, are always too messy for the ideal to be anywhere close to realizable. Hence, for the soft integralist, functionally the Church is better off keeping integralism on the shelf indefinitely as a dead letter (and perhaps should never have tried to implement it even in the past). It’s a doctrine that is only of theoretical interest and too hazardous to apply in practice.

Hard integralism would be the view that it is always best for the Church to try to implement integralism as far as she can, so that Catholics should strive not only to convert the world to the faith, but also to get the state to favor the Church wherever this is practically feasible.

Moderate integralism, naturally, falls in between these extremes. Whereas the soft integralist thinks it is never or almost never a good idea to try practically to implement integralism, and the hard integralist thinks it is always or almost always a good idea to do so, the moderate integralist thinks that there is no “one size fits all” solution and that we have to go case by case. In some historical and cultural contexts, getting the state to favor the Church might be the best policy, in others it might be a very bad policy, and in yet others it might not be clear what the best approach is. We shouldn’t assume a priori that any of these answers is the right one, but should treat the question as prudential and highly contingent on circumstances.

In my opinion, orthodoxy requires a Catholic to be at least what I am calling a soft integralist, but Catholics may legitimately disagree about whether a moderate or hard sort of integralism is preferable. I am sympathetic to the views of Thomas Pink, who has given powerful arguments in defense of the claims that pre-Vatican II teaching is irreformable and that the teaching of Vatican II can be reconciled with it. (Also important are the arguments in defense of a “hermeneutic of continuity” interpretation given by Fr. Brian Harrison and Thomas Storck.)

The situation here is, in my opinion, analogous to the situation vis-à-vis the death penalty. Catholics can legitimately disagree about whether it is ever advisable in practice to resort to capital punishment. But they must all affirm, on pain of heterodoxy, that capital punishment can be legitimate at least in theory. Similarly, Catholics can legitimately disagree about whether it is ever advisable in practice for the state to favor the Church. But they ought to affirm that it can be legitimate at least in theory for the state to do so.

In any event, “Are you for or against integralism?” is not a very helpful question and needs to be disambiguated in the ways I’ve indicated.

Published on June 07, 2019 17:58

June 2, 2019

Continetti on post-liberal conservatism

At the Washington Free Beacon, Matthew Continetti proposes a taxonomy of contemporary American conservatism. Among the groups he identifies are the “post-liberals.” What he means by liberalism is not twentieth- and twenty-first century Democratic Party liberalism, but rather the broader liberal political and philosophical tradition that extends back to Locke, informed the American founding, and was incorporated into the “fusionist” program of Buckley/Reagan-style conservatism. The “post-liberals” are conservatives who think that this broader liberal tradition has become irredeemably corrupt and maybe always has been, and thus judge that the fusionist project of marrying a traditionalist view of morality, family, and religion to the liberal political tradition is incoherent and ought to be abandoned. Continetti notes that post-liberals are “mainly but not exclusively traditionalist Catholics,” and proposes a test for determining whether someone falls into the category:

At the Washington Free Beacon, Matthew Continetti proposes a taxonomy of contemporary American conservatism. Among the groups he identifies are the “post-liberals.” What he means by liberalism is not twentieth- and twenty-first century Democratic Party liberalism, but rather the broader liberal political and philosophical tradition that extends back to Locke, informed the American founding, and was incorporated into the “fusionist” program of Buckley/Reagan-style conservatism. The “post-liberals” are conservatives who think that this broader liberal tradition has become irredeemably corrupt and maybe always has been, and thus judge that the fusionist project of marrying a traditionalist view of morality, family, and religion to the liberal political tradition is incoherent and ought to be abandoned. Continetti notes that post-liberals are “mainly but not exclusively traditionalist Catholics,” and proposes a test for determining whether someone falls into the category:

One way to tell if you are reading a post-liberal is to see what they say about John Locke. If Locke is treated as an important and positive influence on the American founding, then you are dealing with just another American conservative. If Locke is identified as the font of the trans movement and same-sex marriage, then you may have encountered a post-liberal.

End quote. Well, if you’ve read my book Locke , then you know that by this criterion, I am pretty clearly a post-liberal. And frankly, if you look at the world through Aristotelian-Thomistic and/or orthodox Catholic eyes, I think you pretty much have to be some kind of post-liberal. But what kind, exactly? Here things are not as simple as Continetti seems to think.

“The liberal ideology calls for careful discernment”

The late Michael Novak, who was no post-liberal, made a useful distinction between liberal institutions on the one hand, and liberal philosophical foundations on the other. Examples of liberal institutions would be the market economy, limited government and its constitutional constraints, and the rule of law. There is in fact nothing essentiallyliberal about any of these things, but they have certainly come to be closely associated with the modern liberal political order. Examples of liberal philosophical foundations would be Locke’s version of social contract theory, Kant’s conception of human civilization as a kingdom of ends, Rawls’s egalitarian theory of justice, and Nozick’s libertarian theory of justice.

Now, someone could accept some version of the liberal institutions in question while rejecting all of the alternative liberal philosophical foundations.

For example, in my opinion, only someone blinded by ideology could deny the astounding and unequaled power of the market economy to lift human beings out of poverty, or the irrational and impoverishing nature of central planning. Socialism is idiotic as well as evil, and no one who is unwilling to acknowledge that is to be taken seriously on matters of politics and economics. At the same time, it is no less ideologically blinkered to deny the corrosive moral and social consequences of modeling all human relations on market transactions between sovereign individuals, or to deny that private financial power poses grave dangers just as governmental power does. As I argued in my recent Claremont Review of Booksessay on Hayek, liberal individualism undermines the family and national loyalties, which in turn undermines even the preconditions for the stability of the market itself. And the “woke capitalism” of the modern corporation may turn out to be as insidious a threat to the moral order and to freedom of thought and expression as anything the U.S. government has done.

It is possible to affirm both of these sets of thoughts at once – to acknowledge the achievements of so-called liberal institutions while rejecting any liberal philosophical rationale for these institutions. The empirical evidence supports the acknowledgement, whereas, for the post-liberal conservative, philosophical consistency requires the rejection. For, I would argue, you simply cannot marry Catholicism or Thomism to Lockean political philosophy or to Kantianism, much less to Rawlsianism or libertarianism, any more than you can marry them to socialism in any of its noxious varieties.

An important implication of this is that it is fallacious to suppose that a post-liberal conservative must ipso facto be an authoritarian, as many commenters on the recent dispute between David French and Sohrab Ahmari seem to suppose. But it is true that the reasons a post-liberal conservative would oppose authoritarianism are likely to reflect prudence as much as, or more than, principle. For example, a fusionist conservative and a Thomist might agree that it is a bad idea to make adultery a criminal offense. But for the fusionist, who accepts the fundamental liberal assumptions about the purposes of government, that is because such a policy would be an unjust violation of the individual right to personal liberty, which for the liberal includes even the liberty to make grave moral mistakes. By contrast, a Thomist would argue instead that while it would not be per se unjust to make adultery illegal, such a policy is very unlikely to do much good in practice and is likely to produce unintended evils as a side effect.

To be sure, there are also going to be issues on which the post-liberal conservative is bound to insist on holding a paternalistic line as far as possible, where many fusionists are now willing to cave in – for example, on questions about drug legalization, censorship of pornography, the push for transgender rights, and so on. If you think that is “authoritarian,” then you are committed to saying that pretty much all human civilizations before about 20 minutes ago were authoritarian – and have, I submit, drunk very deeply indeed of the liberal individualist Kool-Aid.

Now, exactly how ought institutions like the market to be informed by a non-liberal philosophy such as Thomism? What sorts of specific policies would result? How far should government go in shoring up the moral order, and how far is it even realistic for it to go in the sorry circumstances we now find ourselves in? Those are complicated questions that call for the phronesis of a good statesman as much as they call for theorizing. My own view is that the right theoretical principles are those worked out by Thomist moral and political philosophers in the mid twentieth century under the influence of thinkers like Aristotle, Aquinas, and Bellarmine and the encyclicals of popes Leo XIII and Pius XI, and which are reflected in the manuals of the day.

The point for the moment, though, is just to emphasize that it is a false choice to suppose that one must either follow the fusionist in endorsing some brand of liberalism, or go in for some kind of authoritarianism. Pope Paul VI had his faults, but spoke wisely when he said that “the liberal ideology calls for careful discernment.” What he meant is that the good ends that liberals rightly seek to achieve – he cites “economic efficiency,” “personal initiative,” “the defense of the individual against the increasingly overwhelming hold of organizations,” and “a reaction against the totalitarian tendencies of political powers” – must be disentangled from the bad philosophical assumptions that liberals typically deploy in defense of these good ends. The insinuation that one must accept philosophical liberalism in order to achieve these ends is itself one of the rhetorical tricks of the liberal ideologue’s trade.

Keep political philosophy depoliticized

That brings me to some other remarks from Continetti. He writes:

What the post-liberals seem to call for is the use of government to recapture society from the left. How precisely they intend to accomplish this has been left undefined…

Another question is whether the post-liberal project is sustainable in the first place. The post-liberals… may have over-interpreted the results of the 2016 election. Trump is many things, but it is safe to say that he is not an integralist. Prominent online and in my Twitter feed, the post-liberals might also misjudge their overall numbers…

A conservatism that does not incorporate the ideas of freedom and civil and religious liberty that imprinted America at its birth not only would be unrecognizable to William F. Buckley, Barry Goldwater, and Ronald Reagan. Americans themselves would find it alien and unappealing.

End quote. Speaking just for myself, I haven’t much idea in the first place what a “post-liberal project” is supposed to look like, if that is meant to refer to some sort of practical political program with a set of detailed policy proposals, an electoral strategy, and so on. And like Continetti, I don’t think recent U.S. politics gives much ground for optimism about such a project, however it would be spelled out. The reason I favor a variation on what Continetti calls “post-liberal conservatism” is because I think it is true, not because I think it promises a winning party platform. I understand, of course, that Continetti is a writer on politics (and a good one), for whom questions of what is likely to secure electoral success and legislative victories are of special interest. But questions about what is actually true are, I humbly submit, not entirely unimportant.

If anything, Continetti understates the grounds for pessimism about the prospects for a post-liberal conservative politics. For contemporary Western society is radically out of step with the basic premises to which the post-liberal conservative is committed. Indeed, I would say that liberalism is a Christian heresy and one that seems now to be approaching its full metastasization. I would say that it is the moral and political component of the broader heresy of modernism, which is at high tide and sweeping all before it, the flood now having penetrated deeply into even the innermost parts of the Church. It is like Arianism both in its breathtaking reach and in its longevity. It is worse than Arianism in its depravity. Its god is the self – the sovereign individual of the liberal, and the subjective religious consciousness of the theological modernist – and in seeking to conform reality to the self rather than the self to reality, it tends toward subjectivism, relativism, fideism, voluntarism, and other forms of irrationalism. And there is no limit to the further errors that might follow upon such tendencies. That is why, as Pope Pius X said, modernism is the “synthesis of all heresies.”

Because of this irrationalism, the liberal and modernist personality tends to be dominated by appetite, and by sexual appetite in particular, since the pleasures associated with it are the most intense. But he also has a special hostility to the natural purpose of sex – marital commitment, children, and family – because that imposes the most stringent obligations on the self. The family is also the fundamental social unit, and thus the model for all other social obligations, such as those entailed by ties of nationality. Hence it is inevitable that the liberal and modernist personality will seek to reshape the family, and through it all social order, to conform to his desires. Woke socialism is the last stop on the train ride that begins with radical individualism.

Some readers will no doubt find all of that overwrought, to say the least. The point, however, is that it is a diagnosis that is hard to avoid if one begins with the sorts of premises to which post-liberal conservatives are typically committed. And it entails that an ambitious near-future post-liberal conservative political program is probably not feasible, precisely because, as Continetti says, there simply are not enough voters who still sympathize with that view of the world. In the short term, it seems to me, the post-liberal conservative will have to settle for rearguard actions, piecemeal and often only temporary victories, uneasy alliances with other conservatives, and in general a strategy of muddling through that can hope at best to take the edge off the worst excesses of late stage liberalism.

Where he must be ambitious is in working for the long term revival of Western civilization. For the average person, that means committing oneself firmly to a countercultural way of life – to religious orthodoxy, to having large families, and to preserving the social and cultural inheritance of the past the best one can at the local level, Benedict Option style. For the intellectual, it means working to revive the classical (Platonic, Aristotelian, Scholastic) tradition in Western thought, and showing how it is not only in no way incompatible with, but provides a surer foundation for, the good things that modernity has produced (such as modern science, limited constitutional government, and the market economy).

The good news the post-liberal conservative can give the fusionist is that rejecting liberal philosophical foundations does not entail rejecting these good things, even if it does mean interpreting or modifying them in ways that the fusionist might not like. The bad news is that philosophical liberalism has so eaten away at the moral foundations of Western society that these good things too are threatened along with everything else.

But like the Church, the post-liberal conservative must think in centuries. Arianism did eventually disappear, so thoroughly that in hindsight it is difficult to recall what all the fuss was about. And in the long run liberalism too will disappear, because it is now so deeply contra naturam that its ultimate collapse is inevitable. Future generations will look back and marvel that such a freak show ever existed. What remains to be determined is how much damage it will leave behind it, and how far it will go in persecuting those who resist its ever more extreme permutations.

Now, the dim prospects for short term post-liberal conservative political success can be turned into an advantage. Short term political calculation can make it difficult to think wisely about matters of political philosophy – and has done so with too many contemporary American conservatives, who trim the sails at the level of theory because of what they see in the polls and the ballot box. That is part of the reason so many of them have chucked out the traditionalist side of fusionism, and more or less become libertarians rather than genuine conservatives.

It is easier to resist such temptations when you have no illusions in the first place that your ideas are likely to have much electoral success. You can depoliticizepolitical philosophy in the sense of focusing on inquiring into what is actually true, without being distracted by questions about what will play well with voters or be conducive to forming political alliances. And in the long run, when implementation becomes more feasible, it is also likelier to be successful, because the theory will have been worked out more rigorously.

Here, ironically, the post-liberal conservative can learn something from the founders of fusionist conservatism. Whittaker Chambers famously thought that, by becoming a conservative, he’d joined the losing side. Hayek knew he was a dinosaur, and that to try to revive 19th century style classical liberalism in the 1940s and 1950s was an ambition of Jurassic Park proportions. Buckley made National Review a journal of ideas precisely by attracting disaffected intellectuals like James Burnham, Frank Meyer, and Russell Kirk. They were all free to think and write seriously precisely because they were in the political wilderness. As a result, when the electoral prospects for fusionist conservatism finally did became brighter, there were substantive and well-developed ideas to implement.

Sometimes, when you have less to win, you also have less to lose. That affords a kind of liberty that the post-liberal conservative can enthusiastically embrace.

Related posts:

Hayek’s tragic capitalism

Socialism versus the family

Liberty, equality, fraternity?

Cardinal virtues and counterfeit virtues

Poverty no, inequality si

The conservative critique of libertarianism

Conservatism, populism, and snobbery

Published on June 02, 2019 12:26

May 30, 2019

Rist slapped (Updated)

UPDATE 5/31: Commentary from Fr. Joseph Fessio, Fr. John Zuhlsdorf, and Phil Lawler.

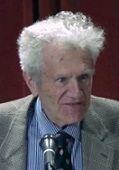

UPDATE 5/31: Commentary from Fr. Joseph Fessio, Fr. John Zuhlsdorf, and Phil Lawler.LifeSite reports that Prof. John Rist, one of the signatories of the recent open letter accusing Pope Francis of heresy, has abruptly been banned from all pontifical universities – which he learned one day by finding himself suddenly denied permission to park his car at the Augustinianum, where he had been doing research. Read the whole thing for the sorry details of the episode.I have been critical of the open letter, but this strikes me as undeservedly shabby treatment. Whatever one thinks of his views, Rist is not some hotheaded pamphleteer or hack blogger. He is a serious thinker, an eminent scholar of classical and early Christian philosophy, the author of many important books, a longtime professor at the Catholic University of America, and a loyal and orthodox son of the Church. It seems to me not irrelevant to point out that he is also 83 years old.

When Vatican officials persistently refuse to address the actual substance of the arguments of critics – and indeed, refuse even just to answer straightforward questions like the dubia – and when heterodox Catholic academics and public intellectuals are largely allowed free rein, this sort of action seems extremely petty, to say the very least. Even dissidents like Hans Küng and Charles Curran, who were disciplined by the Church under Pope St. John Paul II, were first given due process and the opportunity to defend themselves.

There is, to my knowledge, no evidence that Pope Francis himself had anything to do with what has happened. One hopes that, should he learn of it, he will urge the relevant officials to show to Prof. Rist the mercy that the pope has so heavily emphasized during his pontificate.

At Twitter, Matthew Schmitz calls attention to the contrast between the treatment afforded Rist and the way Cardinal Avery Dulles recommended dealing with dissidents. In an earlier post, I discussed Pope Benedict XVI’s manner of dealing with criticism.

Published on May 30, 2019 19:27

Rist slapped

LifeSite reports

that Prof. John Rist, one of the signatories of the recent open letter accusing Pope Francis of heresy, has abruptly been banned from all pontifical universities – which he learned one day by finding himself suddenly denied permission to park his car at the Augustinianum, where he had been doing research. Read the whole thing for the sorry details of the episode. I have been critical of the open letter, but this strikes me as undeservedly shabby treatment. Whatever one thinks of his views, Rist is not some hotheaded pamphleteer or hack blogger. He is a serious thinker, an eminent scholar of classical and early Christian philosophy, the author of many important books, a longtime professor at the Catholic University of America, and a loyal and orthodox son of the Church. It seems to me not irrelevant to point out that he is also 83 years old.

LifeSite reports

that Prof. John Rist, one of the signatories of the recent open letter accusing Pope Francis of heresy, has abruptly been banned from all pontifical universities – which he learned one day by finding himself suddenly denied permission to park his car at the Augustinianum, where he had been doing research. Read the whole thing for the sorry details of the episode. I have been critical of the open letter, but this strikes me as undeservedly shabby treatment. Whatever one thinks of his views, Rist is not some hotheaded pamphleteer or hack blogger. He is a serious thinker, an eminent scholar of classical and early Christian philosophy, the author of many important books, a longtime professor at the Catholic University of America, and a loyal and orthodox son of the Church. It seems to me not irrelevant to point out that he is also 83 years old.When Vatican officials persistently refuse to address the actual substance of the arguments of critics – and indeed, refuse even just to answer straightforward questions like the dubia – and when heterodox Catholic academics and public intellectuals are largely allowed free rein, this sort of action seems extremely petty, to say the very least. Even dissidents like Hans Küng and Charles Curran, who were disciplined by the Church under Pope St. John Paul II, were first given due process and the opportunity to defend themselves.

There is, to my knowledge, no evidence that Pope Francis himself had anything to do with what has happened. One hopes that, should he learn of it, he will urge the relevant officials to show to Prof. Rist the mercy that the pope has so heavily emphasized during his pontificate.

At Twitter, Matthew Schmitz calls attention to the contrast between the treatment afforded Rist and the way Cardinal Avery Dulles recommended dealing with dissidents. In an earlier post, I discussed Pope Benedict XVI’s manner of dealing with criticism.

Published on May 30, 2019 19:27

May 25, 2019

Popes, heresy, and papal heresy

In an interview at National Catholic Register, philosopher John Rist defends his decision to sign the open letter accusing Pope Francis of heresy (on which I commented in an earlier post). At Catholic Herald, canon lawyer Ed Peters argues that the letter fails to establish its main charge. Properly to understand this controversy, it is important to see that a reasonable person could judge that both men have a point – as long as we disambiguate the word “heresy.” What is heresy?

In an interview at National Catholic Register, philosopher John Rist defends his decision to sign the open letter accusing Pope Francis of heresy (on which I commented in an earlier post). At Catholic Herald, canon lawyer Ed Peters argues that the letter fails to establish its main charge. Properly to understand this controversy, it is important to see that a reasonable person could judge that both men have a point – as long as we disambiguate the word “heresy.” What is heresy?

“Heresy” is a word that has both a broader ordinary usage and a narrower technical usage, and both usages have their place. In this respect it is like words such as “assault” or “robbery,” which have both ordinary usages and technical legal usages. If a lady slaps a man for saying something ungentlemanly, most people would probably not think of that as an “assault,” but legally it might be classified that way (even if left unprosecuted). A tax which served to fund no legitimate governmental function would meet the commonsense criterion for “robbery” (the unjust taking of property by force), but no legal code would count it as such.

There is nothing necessarily wrong with such semantic divergence. Ordinary usage is not always precise, but the law needs to be. Hence technical legal definitions don’t always correspond exactly to ordinary usage, even if there is considerable overlap.

The same thing is true of “heresy.” As Parente, Piolanti, and Garofalo’s Dictionary of Dogmatic Theology says, the word “originally… meant a doctrine or doctrinal attitude contrary to the common doctrine of faith” (p. 123). The word derives from the Greek hairesis, which means a “choice” of some elements of Christian doctrine out from among the others, which the heretic rejects. (Heretics, you might say, are the original “pro-choice” types.) Hilaire Belloc notes in The Great Heresies that a heresy involves plucking a theological thesis out from the larger context that gives it its precise meaning, and thereby distorting it.

For example, the heresy of Sabellianism treats Father, Son, and Holy Spirit as mere modes or aspects of one divine Person, rather than as three divine Persons. The reason it does so is that it “chooses” or focuses on God’s unity to the exclusionof his Trinitarian nature. It rejects one aspect of Catholic doctrine in the name of another aspect.

This is the way heresies typically operate. They aren’t made up out of whole cloth. Rather, they start with something that really is there in Catholic doctrine, but focus on it so obsessively and exclusively that they distort it, ignoring other doctrinal elements that balance out the one that the heretic fixates on, and attention to which would have prevented him from falling into error.

Now, suppose a Catholic puts such an emphasis on Christ’s mercy that he takes it to imply that someone in an adulterous second “marriage” can be absolved and receive Holy Communion despite having no intention of refraining from adulterous acts in the future. This would manifestly be a heresy in the original sense cited by the Dictionary, and in the sense explained by Belloc. For it would both be an obvious departure from two millennia of common doctrine, and would involve a distortion of the notion of mercy, turning it into a kind of license to sin.

Indeed, it would be an especially perverse distortion, since it would, in the name of Christ’s teaching on mercy, reverse Christ’s teaching against divorce and remarriage – a teaching that Christ enjoined on his disciples precisely in the name of mercy! For it was, Christ said, only because of their “hardness of heart” that the Israelites were permitted by Moses to divorce, a permission he explicitly cancelled. So, a permissive attitude toward divorce and remarriage is the very last thing one could justify in the name of Christ’s understanding of mercy.

Does Pope Francis endorse such a reversal of traditional teaching? The open letter accuses him of this and other errors. Of course, some of the pope’s statements on doctrinal matters are ambiguous, and in interpreting what a person means, it is only fair to look at the larger context rather than consider an ambiguous statement in isolation. The trouble, the open letter argues, is that the larger context makes things look only worse for the pope, not better. For, the letter notes, the pope has made a series of problematic statements, and refuses to respond even to repeated respectful pleas for clarification from some of his own cardinals and from theologians. Moreover, he praises and promotes churchmen who favor a heterodox interpretation of his words, while criticizing and sidelining those who uphold traditional doctrine.