Jai Arjun Singh's Blog, page 38

August 7, 2018

Help needed for Kambli the desi pup

Attention animal lovers — please read this and see if you can help in any way, or spread the word to anyone else who might be able to.

Archana Sreenivasan is currently fostering Kambli, an 8-month-old paraplegic and incontinent male puppy. He is an Indie and was rescued from a construction site as a 3-month-old with a spinal injury. After that, he was moved to two different shelters, and finally Archana brought him to her home in Bangalore three weeks ago because he wasn't getting the care he needed at the earlier shelter. She is unable to adopt him, and has not been able to find anyone else who can adopt him.

In Archana’s words:

"Kambli will not do well in any shelter in Bangalore. He needs extra care and multiple vet visits, which no shelter will have the bandwidth for. Kambli's urine needs to be expressed 5 times a day and he needs a surface that is smooth for him to drag himself about on (when he's not in his wheel cart.)

"Kambli will not do well in any shelter in Bangalore. He needs extra care and multiple vet visits, which no shelter will have the bandwidth for. Kambli's urine needs to be expressed 5 times a day and he needs a surface that is smooth for him to drag himself about on (when he's not in his wheel cart.)

I came to know that some of the rescue dogs of Delhi are fortunate enough to find homes outside India, in the US, Canada and Netherlands, and I couldn't help dreaming for Kambli. I tried contacting the folks in Delhi who work on these international adoptions but haven't received any response from them.

I can help financially with Kambli. I can have him transported wherever required. I'm willing to help in any other way I possibly can, if anyone is willing to help out with his case.

Kambli needs a home, or he will not survive.”

Among the people Archana is trying to reach are:

Dr. Premalata Choudhary (http://www.choudharypetclinic.com/index.html)

Vandana Anchalia or Kannan Animal Welfare (https://www.facebook.com/kannananimalwelfare/)

But if anyone has suggestions for others who might be able to help, please weigh in. (One complication is that most agencies and shelters - Friendicoes etc - already have more dogs than they can handle, especially with people abandoning pets every day.)

Please feel free to share this post, or the poster I have included. Updates, including videos of Kambli, are on his Instagram page, here.

Please help if you can.

Archana Sreenivasan is currently fostering Kambli, an 8-month-old paraplegic and incontinent male puppy. He is an Indie and was rescued from a construction site as a 3-month-old with a spinal injury. After that, he was moved to two different shelters, and finally Archana brought him to her home in Bangalore three weeks ago because he wasn't getting the care he needed at the earlier shelter. She is unable to adopt him, and has not been able to find anyone else who can adopt him.

In Archana’s words:

"Kambli will not do well in any shelter in Bangalore. He needs extra care and multiple vet visits, which no shelter will have the bandwidth for. Kambli's urine needs to be expressed 5 times a day and he needs a surface that is smooth for him to drag himself about on (when he's not in his wheel cart.)

"Kambli will not do well in any shelter in Bangalore. He needs extra care and multiple vet visits, which no shelter will have the bandwidth for. Kambli's urine needs to be expressed 5 times a day and he needs a surface that is smooth for him to drag himself about on (when he's not in his wheel cart.)I came to know that some of the rescue dogs of Delhi are fortunate enough to find homes outside India, in the US, Canada and Netherlands, and I couldn't help dreaming for Kambli. I tried contacting the folks in Delhi who work on these international adoptions but haven't received any response from them.

I can help financially with Kambli. I can have him transported wherever required. I'm willing to help in any other way I possibly can, if anyone is willing to help out with his case.

Kambli needs a home, or he will not survive.”

Among the people Archana is trying to reach are:

Dr. Premalata Choudhary (http://www.choudharypetclinic.com/index.html)

Vandana Anchalia or Kannan Animal Welfare (https://www.facebook.com/kannananimalwelfare/)

But if anyone has suggestions for others who might be able to help, please weigh in. (One complication is that most agencies and shelters - Friendicoes etc - already have more dogs than they can handle, especially with people abandoning pets every day.)

Please feel free to share this post, or the poster I have included. Updates, including videos of Kambli, are on his Instagram page, here.

Please help if you can.

Published on August 07, 2018 00:24

August 5, 2018

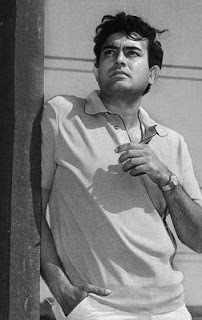

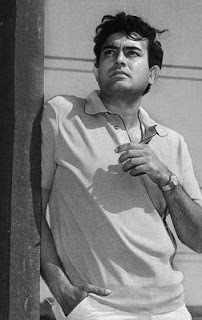

Two faces of Haribhai, a.k.a. Sanjeev Kumar

[Inadvertently continuing the mother theme, with this Mint Lounge piece about my mom's favourite actor. In the early years of blogging, I had many run-ins with Sanjeev Kumar fans because I mocked his Great Actor status. Actually, I was restrained and self-censoring compared to my friend Shamya Dasgupta, who often took over my comments threads and wrote sentences like: “Because Ray was the director, even a fool like Saeed Jaffrey acted well in Shatranj ke Khiladi. Sanjeev Kumar didn't have a choice but to do well."

Anyway, here’s an effort to say some vaguely nice things about SK]

------------------------------

When an acquaintance mentioned recently that Sanjeev Kumar’s 80th birth anniversary had just passed, and wondered why there was no biography of this actor, so admired in his time, I had two contrary responses.

When an acquaintance mentioned recently that Sanjeev Kumar’s 80th birth anniversary had just passed, and wondered why there was no biography of this actor, so admired in his time, I had two contrary responses.

The first went: yes, of course it would be great to have a well-researched book about “Haribhai” (as Kumar, born Harihar Jariwala, was affectionately known). Movie-star biographies – good ones, bad ones – appear nearly every month now, some of them about celebrities who are still in their prime. The recency bias irks me. I often encounter young film buffs who know little about film history, and Kumar is among the old-timers whose work is seen as quaint or stodgy. It’s easy to feel defensive on his behalf.

But the second reaction was a kneejerk one, rooted in my own less-than-kind feelings about Kumar the performer. In fact, a lot of my online time used to be spent mocking the poor man for what I felt was an inflated reputation. One enjoyable blog exchange – nearly 15 years ago – involved a friend and me taking on a Sanjeev Kumar devotee in a thread that became more hysterical and less sincere as it went on. (“Just for the record, Hari didn’t look too bad when he was playing the dhol while his wife made out with Amitabh to Rang Barse,” my friend conceded, tongue-in-cheek.)

Much of our trolling was calculated, aimed at driving our victim into paroxysms of righteous indignation. But it was also rooted in real annoyance about an actor getting disproportionate credit for his choice of roles, for “opting to” playing elderly character parts rather than “heroes”. I had grown up with the idea – expressed by sermonizing adults and by film magazines – that Kumar was a Real Actor, while others were Just Stars. Superb performances by his more glamorous co-stars (Dharmendra and Hema Malini in Sholay, for instance) were downgraded or taken for granted (while SK’s Thakur got all the plaudits for his gritted teeth and trembling lips). This was a simplistic celebration of “subdued” or “understated” over “showy” or “flamboyant”.

Another factor, for me at least, was the tedium generated by numerous bad SK films that continued to be released posthumously right up to the 1990s. I was particularly annoyed by the final scene of Professor ki Padosan, released in 1993: Amitabh Bachchan makes a cameo appearance to say a few nice things about Kumar, then solemnly places a garland over the actor’s photo – all this right at the end of a slapstick comedy, effectively taking the wind out of the audience’s sails and making us feel like we had to stand up for the national anthem.

Which is why it’s fun now to recall another SK avatar: the much younger, mid-1960s version in such films as Nishan and Ali Baba aur 40 Chor. To watch those costume dramas is to see a lithe, beaming young man gamely doing whatever he could with conventional leading roles. These are tacky films by most measures, and I wouldn’t ask you to watch them in their entirety, but look at some scenes like his first appearance in Nishan: an adolescent prince is seen riding and singing along, and then a dissolve gives us the adult version (played by SK), fitted in period costume, long curly hair blowing in the wind.

I’m not saying SK was great in those early roles. He often overdoes things spectacularly (watch him playing drunk while Helen sings “Aap ki Adaon Pe”; the scene at approximately 40 seconds in the YouTube video is unintentional-comedy gold). But in his better moments, he shows personality, panache and a sense of humour, things that faded in later years as he adopted the somber, old-man persona. I feel there’s an element of post-facto myth-building in the idea (often expressed in discussions about SK) that he always set out to be an Actor rather than a Hero. It’s more likely that Kumar would have taken whatever cards were dealt to him by fate and the box-office, but for some combination of intangible reasons, he never found large-scale popularity as a dashing lead. Maybe it’s because he did the wrong films early in his career, or wasn’t conventionally good-looking in the way that Dharmendra or Shashi Kapoor were, or didn’t have the visceral appeal that Rajesh Khanna rode such a wave on. From the mid-70s on, corpulence (brought on partly by alcohol and, rumour has it, romantic rejections) also played a role in his taking on restrained character parts.

Orson Welles once perceptively noted that hamming shouldn’t be synonymous with over-acting. “Ham actors are not all of them strutters and fretters […] a lot of them are understaters, flashing winsome little smiles over the teacups, or scratching their T-shirts.”

Sanjeev Kumar could, at different stages in his career, be both varieties of ham actor, but there was also a middle zone made up of many periods of grace, fueled by scripts and directors – most notably Gulzar, to a lesser extent Basu Bhattacharya, on one occasion Satyajit Ray – who tapped the best of him. Overall I preferred him in lighter parts — in fine comedies like Angoor and Laakhon ki Baat, of course, but also his Satyakam role as the hero’s boisterous friend. Even a non-fan like me can acknowledge that in such films, he found a character’s pulse without being either self-consciously subdued or theatrically over the top.

So, a biography? Bring it on. Just don’t turn it into a Rajkumar Hirani-helmed film with Aamir Khan playing SK as an alien who crashes down into the big bad world of Hindi films and improves it with gravitas.

--------------------------

[Here, in the interests of 'balance', is a piece where I say appreciative things about Kumar - in Gulzar's Koshish. And here's a post about SK and MacMohan - who would play Sambha in Sholay - sharing space together as young supporting actors 10 years before Sholay]

Anyway, here’s an effort to say some vaguely nice things about SK]

------------------------------

When an acquaintance mentioned recently that Sanjeev Kumar’s 80th birth anniversary had just passed, and wondered why there was no biography of this actor, so admired in his time, I had two contrary responses.

When an acquaintance mentioned recently that Sanjeev Kumar’s 80th birth anniversary had just passed, and wondered why there was no biography of this actor, so admired in his time, I had two contrary responses. The first went: yes, of course it would be great to have a well-researched book about “Haribhai” (as Kumar, born Harihar Jariwala, was affectionately known). Movie-star biographies – good ones, bad ones – appear nearly every month now, some of them about celebrities who are still in their prime. The recency bias irks me. I often encounter young film buffs who know little about film history, and Kumar is among the old-timers whose work is seen as quaint or stodgy. It’s easy to feel defensive on his behalf.

But the second reaction was a kneejerk one, rooted in my own less-than-kind feelings about Kumar the performer. In fact, a lot of my online time used to be spent mocking the poor man for what I felt was an inflated reputation. One enjoyable blog exchange – nearly 15 years ago – involved a friend and me taking on a Sanjeev Kumar devotee in a thread that became more hysterical and less sincere as it went on. (“Just for the record, Hari didn’t look too bad when he was playing the dhol while his wife made out with Amitabh to Rang Barse,” my friend conceded, tongue-in-cheek.)

Much of our trolling was calculated, aimed at driving our victim into paroxysms of righteous indignation. But it was also rooted in real annoyance about an actor getting disproportionate credit for his choice of roles, for “opting to” playing elderly character parts rather than “heroes”. I had grown up with the idea – expressed by sermonizing adults and by film magazines – that Kumar was a Real Actor, while others were Just Stars. Superb performances by his more glamorous co-stars (Dharmendra and Hema Malini in Sholay, for instance) were downgraded or taken for granted (while SK’s Thakur got all the plaudits for his gritted teeth and trembling lips). This was a simplistic celebration of “subdued” or “understated” over “showy” or “flamboyant”.

Another factor, for me at least, was the tedium generated by numerous bad SK films that continued to be released posthumously right up to the 1990s. I was particularly annoyed by the final scene of Professor ki Padosan, released in 1993: Amitabh Bachchan makes a cameo appearance to say a few nice things about Kumar, then solemnly places a garland over the actor’s photo – all this right at the end of a slapstick comedy, effectively taking the wind out of the audience’s sails and making us feel like we had to stand up for the national anthem.

Which is why it’s fun now to recall another SK avatar: the much younger, mid-1960s version in such films as Nishan and Ali Baba aur 40 Chor. To watch those costume dramas is to see a lithe, beaming young man gamely doing whatever he could with conventional leading roles. These are tacky films by most measures, and I wouldn’t ask you to watch them in their entirety, but look at some scenes like his first appearance in Nishan: an adolescent prince is seen riding and singing along, and then a dissolve gives us the adult version (played by SK), fitted in period costume, long curly hair blowing in the wind.

I’m not saying SK was great in those early roles. He often overdoes things spectacularly (watch him playing drunk while Helen sings “Aap ki Adaon Pe”; the scene at approximately 40 seconds in the YouTube video is unintentional-comedy gold). But in his better moments, he shows personality, panache and a sense of humour, things that faded in later years as he adopted the somber, old-man persona. I feel there’s an element of post-facto myth-building in the idea (often expressed in discussions about SK) that he always set out to be an Actor rather than a Hero. It’s more likely that Kumar would have taken whatever cards were dealt to him by fate and the box-office, but for some combination of intangible reasons, he never found large-scale popularity as a dashing lead. Maybe it’s because he did the wrong films early in his career, or wasn’t conventionally good-looking in the way that Dharmendra or Shashi Kapoor were, or didn’t have the visceral appeal that Rajesh Khanna rode such a wave on. From the mid-70s on, corpulence (brought on partly by alcohol and, rumour has it, romantic rejections) also played a role in his taking on restrained character parts.

Orson Welles once perceptively noted that hamming shouldn’t be synonymous with over-acting. “Ham actors are not all of them strutters and fretters […] a lot of them are understaters, flashing winsome little smiles over the teacups, or scratching their T-shirts.”

Sanjeev Kumar could, at different stages in his career, be both varieties of ham actor, but there was also a middle zone made up of many periods of grace, fueled by scripts and directors – most notably Gulzar, to a lesser extent Basu Bhattacharya, on one occasion Satyajit Ray – who tapped the best of him. Overall I preferred him in lighter parts — in fine comedies like Angoor and Laakhon ki Baat, of course, but also his Satyakam role as the hero’s boisterous friend. Even a non-fan like me can acknowledge that in such films, he found a character’s pulse without being either self-consciously subdued or theatrically over the top.

So, a biography? Bring it on. Just don’t turn it into a Rajkumar Hirani-helmed film with Aamir Khan playing SK as an alien who crashes down into the big bad world of Hindi films and improves it with gravitas.

--------------------------

[Here, in the interests of 'balance', is a piece where I say appreciative things about Kumar - in Gulzar's Koshish. And here's a post about SK and MacMohan - who would play Sambha in Sholay - sharing space together as young supporting actors 10 years before Sholay]

Published on August 05, 2018 19:00

Rooms, private traps: on living with, and growing away from, a parent

[Re-posting this piece I wrote for Indian Quarterly magazine early last year, about my relationship with my mother — a genuinely close one but also one that had involved very little “casual" talk in recent years. And how that came to be tested when a special situation — her cancer diagnosis — arose in July 2016]

----------------------------------------------------

“Jack is five. He lives in a single, locked room with his Ma.”

(Terse summary on the back cover of Emma Donoghue’s Room)

****

The last film I watched with my mother in a movie hall was the 2015 Room, based on Emma Donoghue’s Booker-shortlisted novel. Two things about that sentence. First: our last film. That sounds bleak and final, and I hope there will be more to come, but at the time of writing there is more reason to be cautious than optimistic.

Second: it wasn’t just the last film we saw together in a hall, it was also the last film we saw together, period. And I can’t think of the last time we saw a whole film together in a more casual, everyday situation, just sitting in front of a TV set while chatting.

But I’ll return to these points.

Here’s how Room became that film. Years ago, before I had read the Donoghue or even known exactly what it was about, I realised that my mother had developed an attachment to it. The novel sat prominently for months on the table where she selected and stacked books that had come to me from various publishers, and whose titles or synopses -- or jacket covers -- she had found intriguing. The great majority of those books were abandoned after a few pages when she found they weren’t up her street, but Room she finished, over many sessions of sporadic reading: putting the book down after a few pages, returning to it between her dalliances with less demanding things such as movie magazines.

It wasn’t until I heard about the upcoming film version, and read plot details online, that I learnt what Room was about. And then, knowing that the film was going to show in Delhi and that mum might like to see it, I read the novel myself as preparation, and found myself thinking anew about what she might have found so compelling.

Room is told in the voice of a five-year-old boy who has spent his whole life with his mother in a single small room where she has been kept captive since being kidnapped as a teenager. Here are two people who have been victims of a terrible, ongoing crime -- one of them in full possession of the facts, nurturing and guarding and making up stories for the other, who is still innocent and unaware that there is a life and a world beyond the tiny space he has known all his short life.

This is, needless to say, an extraordinary narrative situation. The broad premise, and what occurs within it, might be considered unrealistic -- or at least, very improbable -- but it also contains an allegory for aspects of a more “normal” mother-child relationship, especially a close one that involves a great deal of mutual interdependence. First there is the womb, a safe space from which the child must eventually be ejected to discover the outside world; and then, in that outside world, there is a still larger “room”, the sheltering one of parenthood, which this infant will stay encased in for at least a few years. Simultaneously the parent must prepare to “free” herself from the belief -- with its attendant agonies and ecstasies -- that she alone can walk her child through life.

Did my mother think about any of this when she became so involved with the book? I don’t know, I haven’t asked her (and I won’t), but even if she had, it would probably have been in a subconscious way; she wouldn’t have articulated these thoughts like I just did, all pedantic and reviewer-like. More than a tendency to intellectualise, she has always had what I think of as an intuitive, commonsense wisdom. (The only "literary" observation she made to me about the novel was that she had been first taken aback and disoriented, then gradually fascinated, by Jack’s fumbling first-person narrative; it took her a while to see that the reader was meant to understand more about the situation than the narrator himself did.)

Still, I wonder if she thought about my childhood.

******

“Jack is five. He lives in a single, locked room with his Ma.”

Jai is eight. He and his mother stay locked up in a room at the end of the house, down the hall -- not all the time, but on days when things are especially bad at home; when the big bad wolf huffs and puffs and threatens to blow the door down.

We were always exceptionally close. She was my life-raft on a sea of uncertainty, at an age when I barely knew enough to be certain or uncertain about anything; a shield not just from my father’s unpredictable, alcohol-fuelled violence but also -- and this I realised only much later -- from the possibility of my becoming over-pampered, turned into a privileged lout, by well-off grandparents trying too hard to compensate for their son’s behaviour.

I don’t want to get too dramatic about this: our lives were never close to being as bad as those of Room’s protagonists. The terrifying memories -- of my father hammering on a locked door, or overturning a huge, heaped dining table with unfathomable strength, or physically assaulting a Sikh priest who was reading from the Granth Sahib during an akhand paath in our house -- intersect with other memories of going to school; going (once in a while) to friends’ parties; of mum taking up a part-time job as a doctor’s receptionist when she found that her monthly pocket money wasn’t enough (and maybe that she needed to feel useful). But the bad memories are always there too, and aspects of our life certainly felt horror film-ish -- the many times we had to sneak out when it got dark, for instance, and spend a scared night at a neighbour’s place, or in the maid’s quarters behind the house.

I don’t want to get too dramatic about this: our lives were never close to being as bad as those of Room’s protagonists. The terrifying memories -- of my father hammering on a locked door, or overturning a huge, heaped dining table with unfathomable strength, or physically assaulting a Sikh priest who was reading from the Granth Sahib during an akhand paath in our house -- intersect with other memories of going to school; going (once in a while) to friends’ parties; of mum taking up a part-time job as a doctor’s receptionist when she found that her monthly pocket money wasn’t enough (and maybe that she needed to feel useful). But the bad memories are always there too, and aspects of our life certainly felt horror film-ish -- the many times we had to sneak out when it got dark, for instance, and spend a scared night at a neighbour’s place, or in the maid’s quarters behind the house.

And yes, ultimately, there is no undramatic way of putting this, we did "escape". Aided by the confidence we had in our relationship, and the rock-solid support of my mother’s widowed mother, who -- her own troubles notwithstanding -- took us in hand when she realised that things had gone out of control. After a mercifully brief custody battle, we ended up living together in a then-very-green-and-quiet south Delhi colony called Saket, which means “heaven”. (But I won’t underline that. Mustn’t get too dramatic.)

*****

A few years after this, my interest in cinema as something one could think about, read in depth about, perhaps even write professionally about one day, began with Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, and the reservoirs of film literature it led me to. By this point my mother and I were leading secure enough lives that it was possible to smile at the film’s macabre Oedipal theme. Mum (or Amma as I have always called her for some reason, late as it is in this piece to reveal such a central piece of information) told me how, in the early 1960s when the film released in Bombay, her brother came home and solemnly informed their mother that he would like to have her “mummified” after she had passed on.

(“Needles, sawdust… the chemicals are the only things that cost anything,” Norman Bates says, explaining the practicalities of taxidermy; a horror-movie monster, yes, but also someone who knows what it is like to be so close to and so dependent on a parent that you want to keep their physical presence with you “forever”.)

Despite the emotional security that had come with leaving my father’s house, I was cripplingly shy, prone to melancholia and loneliness. And watching it when I did, Psycho touched something deep in me. I found sadness in it, in scenes like the one where Norman responds to the insinuation that he and his mother might have been looking for money to leave their motel and start a new life elsewhere. “This place happens to be my only world,” he says, “I grew up in that house up there. I had a very happy childhood.” He sounds defiant. “My mother and I were more than happy.”

Perhaps on some level, without being able to express it this way at age 14, I was instinctively realising how close I had come to leading the trapped, circumscribed life that Norman and his dead mother do. But then, as he says in the film’s most moving sequence, a long conversation with a conflicted young woman who has “gotten off the main road”, we are all clamped in our private traps anyway -- even when we seem free. “We scratch and we claw, but only at the air, only at each other.”

*******

Imprisonment, Dependence, Liberation, Self-discovery, Stagnation… those are some big themes, and despite my professed reluctance to get dramatic, I can’t help returning to them. And it isn’t just by chance that I have been talking about two films that involve very intense mother-son relationships and the very unusual situations in which those relationships grow, ossify or decay. I have in recent years become aware of a glitch in my relationship with my mother. Put briefly: it seems that our closeness has almost always been founded on big things -- the Important and the Dramatic -- and not enough on the minutiae of life; the Casual, the Mundane.

From the beginning we always shared the really important stuff, and I never thought this was unusual until I heard stories about all the things my friends -- even the ones from the seemingly open-minded, cosmopolitan families -- routinely hid from their parents: about girlfriends, or bunking college, or their first cigarette. When I took my girlfriend -- a young woman in an unhappy marriage, on the brink of separation -- across to meet my mother for the first time, I felt none of the nervousness that most other young people I knew would feel in that situation. It was the most natural thing to do.

And this flowed from how things had always been between us, from my mother’s own openness. When I couldn’t have been more than 12 or 13, she told me about the marriage proposal she had got from an uncle, a childhood friend who had always held a torch for her, and how she had been very tempted but didn’t take it up because it would mean relocating to Lagos, too large a bridge for us to cross at that point in our lives. On another occasion, when the husband of one of her neighbourhood friends made a sexual overture -- figuring that a divorced woman was easy pickings -- I was the first to hear of it, and to be privy to her shock as well as her fear that she may have brought it upon herself by bantering with him at social gatherings.

And this flowed from how things had always been between us, from my mother’s own openness. When I couldn’t have been more than 12 or 13, she told me about the marriage proposal she had got from an uncle, a childhood friend who had always held a torch for her, and how she had been very tempted but didn’t take it up because it would mean relocating to Lagos, too large a bridge for us to cross at that point in our lives. On another occasion, when the husband of one of her neighbourhood friends made a sexual overture -- figuring that a divorced woman was easy pickings -- I was the first to hear of it, and to be privy to her shock as well as her fear that she may have brought it upon herself by bantering with him at social gatherings.

Taking as much pride as I did in this candour, it took me a long time to discover that I may be undervaluing other sorts of conversations and interactions: the small talk that keeps people going day by day; the sort of behaviour that introverts sometimes dismiss as flippant or inconsequential, but which in its own way brings nourishment and meaning to a relationship over time. Casual chatter and gossip are ways of ventilating the heart, an old grandmother says in Marjane Satrapi’s graphic novel Embroideries. In Yasujiro Ozu’s 1959 film Good Morning, when a little boy tells his parents that he’s fed up of their polite, vacuous conversation -- the repeated “good mornings” and “how are yous”, which seem vacuous or hypocritical -- one of them responds that such talk is essential: “It's a lubricant for the world.”

My mother and I never quite learnt these lessons -- or perhaps we knew them once and gradually became careless about them. Partly this was a personality matter -- both of us being, to different degrees, very private people -- and partly a result of circumstances; for many years while growing up I was intimidated by my nani’s boisterous personality and kept to my room while she was around. But it also reflects the growing-away-from-a-parent process that everyone (except, maybe, a Norman Bates) goes through.

The second half of Donoghue’s Room is made sharply poignant by the mother’s realisation that her son will never again be as dependent on her as he was during their years of incarceration. I have never really lived away from my mother -- even after getting married and shifting to another flat in the same colony, I continued spending my working day as a freelance writer in my old room, my comfort zone, in her house. But like most children do, I moved away in other ways: into new worlds populated by new friends, into a job and the circles it introduced me to, but also into my own inner spaces.

There was a time, long ago, when we played Scrabble together, or watched TV shows together, in the first years after satellite TV came to India. This gradually stopped. As I became embarrassed by the tackiness of some of the Hindi films we rented and watched on videocassette every Friday, I started lingering about outside the room where mum and nani were watching the film -- and shortly afterwards, I moved away from Hindi cinema altogether, and into new realms that excluded my mother. One thing followed another, and casual conversation became increasingly hard; we rarely even sat down and had meals together. Despite living in the same house, we became… not estranged, but something else -- something I don’t know the word for.

There was a time, long ago, when we played Scrabble together, or watched TV shows together, in the first years after satellite TV came to India. This gradually stopped. As I became embarrassed by the tackiness of some of the Hindi films we rented and watched on videocassette every Friday, I started lingering about outside the room where mum and nani were watching the film -- and shortly afterwards, I moved away from Hindi cinema altogether, and into new realms that excluded my mother. One thing followed another, and casual conversation became increasingly hard; we rarely even sat down and had meals together. Despite living in the same house, we became… not estranged, but something else -- something I don’t know the word for.

Can a relationship that is really, really close in essence also be distant and awkward in some important contexts? And when a new sort of special situation comes around -- one that demands an everyday intimacy -- what then?

********

I have had to think about these things ever since the day last July when I sat down to talk with mum about what I thought would be a relatively mundane medical issue -- her lingering discomfort and back pain, which I’d assumed was an offshoot of an old kidney condition, worsened by many years of self-medicating -- and she told me, all matter of fact, “No, it isn’t the kidney. It’s breast cancer. I have had it for a while, so it’s probably quite advanced by now.”

World-altering though that moment was, it’s almost funny when I think of it now. The fan whirring above us. A reality show playing on low volume in the background. Me, having come into her room, knowing her aversion to doctors and hospitals, with a speech carefully prepared to put her at ease (“We’ll go once, it’ll take just 10 minutes, you can tell them what medicines you’ve been taking, they’ll tell us if there’s something else you should be doing, and that’s it... you don’t have to agree to any intrusive procedures or examinations if you aren’t comfortable”), the deadpan look on her face as I recited the first two or three sentences of that speech -- as casually as I could, looking around as I said the words, at the dog, at the TV, so she wouldn’t think I was arm-twisting her -- and then her interrupting me with her grand revelation: oh no, this is the start of something much bigger than you think.

Another case of what should have been a quotidian exchange turning into something larger than life, like old Hindi movies about terminally ill patients. Another demonstration that the ‘Casual’ switch is jammed when it comes to the two of us.

In the weeks that followed -- a fortnight-long hospital stint precipitated by a worried-looking oncologist saying “Can we admit her right now? It’s important”; the realization that my mother, with her ridiculously high pain threshold, had a cancer-caused crack in her spine, which had to be mended before anything else could be done; the days and nights divided between handling things in the hospital and looking after our high-strung canine child Lara, who had been completely dependent on mum; watching the deterioration and immobilization of a woman who, to my eyes at least, had seemed in decent shape for her 63 years just a few weeks earlier, certainly capable of living alone -- through all this and more, I had plenty of time to wonder how it had come to this: how a mother whom I saw every day had been diagnosed so late that the disease was almost certainly incurable; why it had to be her closest friend, an aunt who lived downstairs, who alerted me with a couple of phone calls to say that mum was in so much pain late at night that she had -- and this was the biggest red light of all -- been unable to feed Lara.

And, naturally, I couldn’t help thinking that if I had spent more “casual” time with her in the previous few months -- even sitting around in the evenings in her room for 15-20 minutes each day while she watched TV or listened to music -- I would have been more alert to the little signs, the displays of pain that she had kept hidden.

*****

One side-effect of mum’s chemotherapy is that it has made her sentimental about little things, and at unexpected times. One day, apropos of nothing, she asked if I would massage her aching shoulder for a bit -- and then, smiling, squeezing my hand, told her nurse that I had “the healing touch”. And I winced. Only momentarily, but I couldn’t help it; this overt display of closeness and affection was discomfiting.

Visiting the toy store Hamleys with a friend and his little daughter the next day, I idly glanced at art-and-craft games that I thought might be useful for mum -- not so much to pass the time but to keep her mind active, since people with lesions in the brain, and risk of seizures or mental atrophy, need to do this. Soon I realised that I was looking mainly at the one-person activities. Given that I had flexible working hours, which I mostly spent in her house, shouldn’t I have made an effort to find something we could share, if only for a few minutes each day? Was I nervous about the small talk that would inevitably accompany such a joint endeavour? Or was I afraid that such proximity would make me privy to the involuntary groans of pain that came from her when she moved her shoulder or back at an awkward angle? And in either case, what did that say about me -- “such a good, dutiful son”, as I am often called by visitors to the house?

But even with the knowledge that time may be running out and every day is precious, how do you suddenly begin doing the things you haven’t been accustomed to doing for years? How do you force yourself to sit down and chat about “trivial” or “inconsequential” things, or just play Scrabble, with a parent-patient who might need a psychological boost, when the two of you have long fallen out of that habit and become locked in your own little boxes?

Inevitably, given the situation, the bulk of our interactions are about urgent and important things: I walk into her room at fixed intervals to check on her medicine intake and her meals, to confirm a blood-sample appointment, to discuss contacting a new nursing agency when the current one raises its fees. But I’m also making efforts now -- small, self-conscious, not very successful ones -- to turns things around: to chat with her about the currency situation, or banter about whether her post-cancer wig is more convincing than Donald Trump’s real hair, or show her a joke someone had shared on Facebook.

Still confined to our own rooms. Stuck in private traps. But trying.

---------------------------------------------------------------

[An earlier post about caregiving is here. And here is my long essay about Hindi-movie mothers for a Zubaan anthology]

----------------------------------------------------

“Jack is five. He lives in a single, locked room with his Ma.”

(Terse summary on the back cover of Emma Donoghue’s Room)

****

The last film I watched with my mother in a movie hall was the 2015 Room, based on Emma Donoghue’s Booker-shortlisted novel. Two things about that sentence. First: our last film. That sounds bleak and final, and I hope there will be more to come, but at the time of writing there is more reason to be cautious than optimistic.

Second: it wasn’t just the last film we saw together in a hall, it was also the last film we saw together, period. And I can’t think of the last time we saw a whole film together in a more casual, everyday situation, just sitting in front of a TV set while chatting.

But I’ll return to these points.

Here’s how Room became that film. Years ago, before I had read the Donoghue or even known exactly what it was about, I realised that my mother had developed an attachment to it. The novel sat prominently for months on the table where she selected and stacked books that had come to me from various publishers, and whose titles or synopses -- or jacket covers -- she had found intriguing. The great majority of those books were abandoned after a few pages when she found they weren’t up her street, but Room she finished, over many sessions of sporadic reading: putting the book down after a few pages, returning to it between her dalliances with less demanding things such as movie magazines.

It wasn’t until I heard about the upcoming film version, and read plot details online, that I learnt what Room was about. And then, knowing that the film was going to show in Delhi and that mum might like to see it, I read the novel myself as preparation, and found myself thinking anew about what she might have found so compelling.

Room is told in the voice of a five-year-old boy who has spent his whole life with his mother in a single small room where she has been kept captive since being kidnapped as a teenager. Here are two people who have been victims of a terrible, ongoing crime -- one of them in full possession of the facts, nurturing and guarding and making up stories for the other, who is still innocent and unaware that there is a life and a world beyond the tiny space he has known all his short life.

This is, needless to say, an extraordinary narrative situation. The broad premise, and what occurs within it, might be considered unrealistic -- or at least, very improbable -- but it also contains an allegory for aspects of a more “normal” mother-child relationship, especially a close one that involves a great deal of mutual interdependence. First there is the womb, a safe space from which the child must eventually be ejected to discover the outside world; and then, in that outside world, there is a still larger “room”, the sheltering one of parenthood, which this infant will stay encased in for at least a few years. Simultaneously the parent must prepare to “free” herself from the belief -- with its attendant agonies and ecstasies -- that she alone can walk her child through life.

Did my mother think about any of this when she became so involved with the book? I don’t know, I haven’t asked her (and I won’t), but even if she had, it would probably have been in a subconscious way; she wouldn’t have articulated these thoughts like I just did, all pedantic and reviewer-like. More than a tendency to intellectualise, she has always had what I think of as an intuitive, commonsense wisdom. (The only "literary" observation she made to me about the novel was that she had been first taken aback and disoriented, then gradually fascinated, by Jack’s fumbling first-person narrative; it took her a while to see that the reader was meant to understand more about the situation than the narrator himself did.)

Still, I wonder if she thought about my childhood.

******

“Jack is five. He lives in a single, locked room with his Ma.”

Jai is eight. He and his mother stay locked up in a room at the end of the house, down the hall -- not all the time, but on days when things are especially bad at home; when the big bad wolf huffs and puffs and threatens to blow the door down.

We were always exceptionally close. She was my life-raft on a sea of uncertainty, at an age when I barely knew enough to be certain or uncertain about anything; a shield not just from my father’s unpredictable, alcohol-fuelled violence but also -- and this I realised only much later -- from the possibility of my becoming over-pampered, turned into a privileged lout, by well-off grandparents trying too hard to compensate for their son’s behaviour.

I don’t want to get too dramatic about this: our lives were never close to being as bad as those of Room’s protagonists. The terrifying memories -- of my father hammering on a locked door, or overturning a huge, heaped dining table with unfathomable strength, or physically assaulting a Sikh priest who was reading from the Granth Sahib during an akhand paath in our house -- intersect with other memories of going to school; going (once in a while) to friends’ parties; of mum taking up a part-time job as a doctor’s receptionist when she found that her monthly pocket money wasn’t enough (and maybe that she needed to feel useful). But the bad memories are always there too, and aspects of our life certainly felt horror film-ish -- the many times we had to sneak out when it got dark, for instance, and spend a scared night at a neighbour’s place, or in the maid’s quarters behind the house.

I don’t want to get too dramatic about this: our lives were never close to being as bad as those of Room’s protagonists. The terrifying memories -- of my father hammering on a locked door, or overturning a huge, heaped dining table with unfathomable strength, or physically assaulting a Sikh priest who was reading from the Granth Sahib during an akhand paath in our house -- intersect with other memories of going to school; going (once in a while) to friends’ parties; of mum taking up a part-time job as a doctor’s receptionist when she found that her monthly pocket money wasn’t enough (and maybe that she needed to feel useful). But the bad memories are always there too, and aspects of our life certainly felt horror film-ish -- the many times we had to sneak out when it got dark, for instance, and spend a scared night at a neighbour’s place, or in the maid’s quarters behind the house. And yes, ultimately, there is no undramatic way of putting this, we did "escape". Aided by the confidence we had in our relationship, and the rock-solid support of my mother’s widowed mother, who -- her own troubles notwithstanding -- took us in hand when she realised that things had gone out of control. After a mercifully brief custody battle, we ended up living together in a then-very-green-and-quiet south Delhi colony called Saket, which means “heaven”. (But I won’t underline that. Mustn’t get too dramatic.)

*****

A few years after this, my interest in cinema as something one could think about, read in depth about, perhaps even write professionally about one day, began with Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, and the reservoirs of film literature it led me to. By this point my mother and I were leading secure enough lives that it was possible to smile at the film’s macabre Oedipal theme. Mum (or Amma as I have always called her for some reason, late as it is in this piece to reveal such a central piece of information) told me how, in the early 1960s when the film released in Bombay, her brother came home and solemnly informed their mother that he would like to have her “mummified” after she had passed on.

(“Needles, sawdust… the chemicals are the only things that cost anything,” Norman Bates says, explaining the practicalities of taxidermy; a horror-movie monster, yes, but also someone who knows what it is like to be so close to and so dependent on a parent that you want to keep their physical presence with you “forever”.)

Despite the emotional security that had come with leaving my father’s house, I was cripplingly shy, prone to melancholia and loneliness. And watching it when I did, Psycho touched something deep in me. I found sadness in it, in scenes like the one where Norman responds to the insinuation that he and his mother might have been looking for money to leave their motel and start a new life elsewhere. “This place happens to be my only world,” he says, “I grew up in that house up there. I had a very happy childhood.” He sounds defiant. “My mother and I were more than happy.”

Perhaps on some level, without being able to express it this way at age 14, I was instinctively realising how close I had come to leading the trapped, circumscribed life that Norman and his dead mother do. But then, as he says in the film’s most moving sequence, a long conversation with a conflicted young woman who has “gotten off the main road”, we are all clamped in our private traps anyway -- even when we seem free. “We scratch and we claw, but only at the air, only at each other.”

*******

Imprisonment, Dependence, Liberation, Self-discovery, Stagnation… those are some big themes, and despite my professed reluctance to get dramatic, I can’t help returning to them. And it isn’t just by chance that I have been talking about two films that involve very intense mother-son relationships and the very unusual situations in which those relationships grow, ossify or decay. I have in recent years become aware of a glitch in my relationship with my mother. Put briefly: it seems that our closeness has almost always been founded on big things -- the Important and the Dramatic -- and not enough on the minutiae of life; the Casual, the Mundane.

From the beginning we always shared the really important stuff, and I never thought this was unusual until I heard stories about all the things my friends -- even the ones from the seemingly open-minded, cosmopolitan families -- routinely hid from their parents: about girlfriends, or bunking college, or their first cigarette. When I took my girlfriend -- a young woman in an unhappy marriage, on the brink of separation -- across to meet my mother for the first time, I felt none of the nervousness that most other young people I knew would feel in that situation. It was the most natural thing to do.

And this flowed from how things had always been between us, from my mother’s own openness. When I couldn’t have been more than 12 or 13, she told me about the marriage proposal she had got from an uncle, a childhood friend who had always held a torch for her, and how she had been very tempted but didn’t take it up because it would mean relocating to Lagos, too large a bridge for us to cross at that point in our lives. On another occasion, when the husband of one of her neighbourhood friends made a sexual overture -- figuring that a divorced woman was easy pickings -- I was the first to hear of it, and to be privy to her shock as well as her fear that she may have brought it upon herself by bantering with him at social gatherings.

And this flowed from how things had always been between us, from my mother’s own openness. When I couldn’t have been more than 12 or 13, she told me about the marriage proposal she had got from an uncle, a childhood friend who had always held a torch for her, and how she had been very tempted but didn’t take it up because it would mean relocating to Lagos, too large a bridge for us to cross at that point in our lives. On another occasion, when the husband of one of her neighbourhood friends made a sexual overture -- figuring that a divorced woman was easy pickings -- I was the first to hear of it, and to be privy to her shock as well as her fear that she may have brought it upon herself by bantering with him at social gatherings.Taking as much pride as I did in this candour, it took me a long time to discover that I may be undervaluing other sorts of conversations and interactions: the small talk that keeps people going day by day; the sort of behaviour that introverts sometimes dismiss as flippant or inconsequential, but which in its own way brings nourishment and meaning to a relationship over time. Casual chatter and gossip are ways of ventilating the heart, an old grandmother says in Marjane Satrapi’s graphic novel Embroideries. In Yasujiro Ozu’s 1959 film Good Morning, when a little boy tells his parents that he’s fed up of their polite, vacuous conversation -- the repeated “good mornings” and “how are yous”, which seem vacuous or hypocritical -- one of them responds that such talk is essential: “It's a lubricant for the world.”

My mother and I never quite learnt these lessons -- or perhaps we knew them once and gradually became careless about them. Partly this was a personality matter -- both of us being, to different degrees, very private people -- and partly a result of circumstances; for many years while growing up I was intimidated by my nani’s boisterous personality and kept to my room while she was around. But it also reflects the growing-away-from-a-parent process that everyone (except, maybe, a Norman Bates) goes through.

The second half of Donoghue’s Room is made sharply poignant by the mother’s realisation that her son will never again be as dependent on her as he was during their years of incarceration. I have never really lived away from my mother -- even after getting married and shifting to another flat in the same colony, I continued spending my working day as a freelance writer in my old room, my comfort zone, in her house. But like most children do, I moved away in other ways: into new worlds populated by new friends, into a job and the circles it introduced me to, but also into my own inner spaces.

There was a time, long ago, when we played Scrabble together, or watched TV shows together, in the first years after satellite TV came to India. This gradually stopped. As I became embarrassed by the tackiness of some of the Hindi films we rented and watched on videocassette every Friday, I started lingering about outside the room where mum and nani were watching the film -- and shortly afterwards, I moved away from Hindi cinema altogether, and into new realms that excluded my mother. One thing followed another, and casual conversation became increasingly hard; we rarely even sat down and had meals together. Despite living in the same house, we became… not estranged, but something else -- something I don’t know the word for.

There was a time, long ago, when we played Scrabble together, or watched TV shows together, in the first years after satellite TV came to India. This gradually stopped. As I became embarrassed by the tackiness of some of the Hindi films we rented and watched on videocassette every Friday, I started lingering about outside the room where mum and nani were watching the film -- and shortly afterwards, I moved away from Hindi cinema altogether, and into new realms that excluded my mother. One thing followed another, and casual conversation became increasingly hard; we rarely even sat down and had meals together. Despite living in the same house, we became… not estranged, but something else -- something I don’t know the word for.Can a relationship that is really, really close in essence also be distant and awkward in some important contexts? And when a new sort of special situation comes around -- one that demands an everyday intimacy -- what then?

********

I have had to think about these things ever since the day last July when I sat down to talk with mum about what I thought would be a relatively mundane medical issue -- her lingering discomfort and back pain, which I’d assumed was an offshoot of an old kidney condition, worsened by many years of self-medicating -- and she told me, all matter of fact, “No, it isn’t the kidney. It’s breast cancer. I have had it for a while, so it’s probably quite advanced by now.”

World-altering though that moment was, it’s almost funny when I think of it now. The fan whirring above us. A reality show playing on low volume in the background. Me, having come into her room, knowing her aversion to doctors and hospitals, with a speech carefully prepared to put her at ease (“We’ll go once, it’ll take just 10 minutes, you can tell them what medicines you’ve been taking, they’ll tell us if there’s something else you should be doing, and that’s it... you don’t have to agree to any intrusive procedures or examinations if you aren’t comfortable”), the deadpan look on her face as I recited the first two or three sentences of that speech -- as casually as I could, looking around as I said the words, at the dog, at the TV, so she wouldn’t think I was arm-twisting her -- and then her interrupting me with her grand revelation: oh no, this is the start of something much bigger than you think.

Another case of what should have been a quotidian exchange turning into something larger than life, like old Hindi movies about terminally ill patients. Another demonstration that the ‘Casual’ switch is jammed when it comes to the two of us.

In the weeks that followed -- a fortnight-long hospital stint precipitated by a worried-looking oncologist saying “Can we admit her right now? It’s important”; the realization that my mother, with her ridiculously high pain threshold, had a cancer-caused crack in her spine, which had to be mended before anything else could be done; the days and nights divided between handling things in the hospital and looking after our high-strung canine child Lara, who had been completely dependent on mum; watching the deterioration and immobilization of a woman who, to my eyes at least, had seemed in decent shape for her 63 years just a few weeks earlier, certainly capable of living alone -- through all this and more, I had plenty of time to wonder how it had come to this: how a mother whom I saw every day had been diagnosed so late that the disease was almost certainly incurable; why it had to be her closest friend, an aunt who lived downstairs, who alerted me with a couple of phone calls to say that mum was in so much pain late at night that she had -- and this was the biggest red light of all -- been unable to feed Lara.

And, naturally, I couldn’t help thinking that if I had spent more “casual” time with her in the previous few months -- even sitting around in the evenings in her room for 15-20 minutes each day while she watched TV or listened to music -- I would have been more alert to the little signs, the displays of pain that she had kept hidden.

*****

One side-effect of mum’s chemotherapy is that it has made her sentimental about little things, and at unexpected times. One day, apropos of nothing, she asked if I would massage her aching shoulder for a bit -- and then, smiling, squeezing my hand, told her nurse that I had “the healing touch”. And I winced. Only momentarily, but I couldn’t help it; this overt display of closeness and affection was discomfiting.

Visiting the toy store Hamleys with a friend and his little daughter the next day, I idly glanced at art-and-craft games that I thought might be useful for mum -- not so much to pass the time but to keep her mind active, since people with lesions in the brain, and risk of seizures or mental atrophy, need to do this. Soon I realised that I was looking mainly at the one-person activities. Given that I had flexible working hours, which I mostly spent in her house, shouldn’t I have made an effort to find something we could share, if only for a few minutes each day? Was I nervous about the small talk that would inevitably accompany such a joint endeavour? Or was I afraid that such proximity would make me privy to the involuntary groans of pain that came from her when she moved her shoulder or back at an awkward angle? And in either case, what did that say about me -- “such a good, dutiful son”, as I am often called by visitors to the house?

But even with the knowledge that time may be running out and every day is precious, how do you suddenly begin doing the things you haven’t been accustomed to doing for years? How do you force yourself to sit down and chat about “trivial” or “inconsequential” things, or just play Scrabble, with a parent-patient who might need a psychological boost, when the two of you have long fallen out of that habit and become locked in your own little boxes?

Inevitably, given the situation, the bulk of our interactions are about urgent and important things: I walk into her room at fixed intervals to check on her medicine intake and her meals, to confirm a blood-sample appointment, to discuss contacting a new nursing agency when the current one raises its fees. But I’m also making efforts now -- small, self-conscious, not very successful ones -- to turns things around: to chat with her about the currency situation, or banter about whether her post-cancer wig is more convincing than Donald Trump’s real hair, or show her a joke someone had shared on Facebook.

Still confined to our own rooms. Stuck in private traps. But trying.

---------------------------------------------------------------

[An earlier post about caregiving is here. And here is my long essay about Hindi-movie mothers for a Zubaan anthology]

Published on August 05, 2018 04:51

August 1, 2018

Fractured narratives in Feroz Rather’s Night of Broken Glass

[Did this short review of an intriguing but uneven new Kashmir book for India Today]

-------------------------------------------

In one of the many interconnected stories in Feroz Rather's The Night of Broken Glass , a tyrannical Army major watches Hitchcock’s Rope on TV. As the passage becomes increasingly surreal, his private reminiscences merge with scenes from the film.

Like Rope, which was about a motive-less murder, Rather's book centres on tragic, untimely deaths and destructive hubris. But unlike the film, famously made up of long takes, The Night of Broken Glass is filled with the literary equivalents of slow dissolves. One story plays alongside and informs another. Voices and perspectives change. Chronology is uncertain. Nightmare scenes are told with the lucidity of reportage, and actual incidents related as if they were nightmares. The writing is raw and vulnerable and sometimes meandering, as if to capture the rhythms of oral storytelling.

Like Rope, which was about a motive-less murder, Rather's book centres on tragic, untimely deaths and destructive hubris. But unlike the film, famously made up of long takes, The Night of Broken Glass is filled with the literary equivalents of slow dissolves. One story plays alongside and informs another. Voices and perspectives change. Chronology is uncertain. Nightmare scenes are told with the lucidity of reportage, and actual incidents related as if they were nightmares. The writing is raw and vulnerable and sometimes meandering, as if to capture the rhythms of oral storytelling.

All this adds up to an unusual, restless narrative that looks at the violence in Kashmir mainly through the experiences of young people who smoke Revolution cigarettes, wear Liberty shoes and strive for “Azaadi”, usually to no avail. A boy makes a rosary out of bullet shells collected by his father. A journalist writes a resignation letter to her boss, denouncing a profession made up of complacent, power-drunk men. (Later, the boss gets to speak to us too.) A story where a man finds himself looking after a cancer-ridden shell of a body, belonging to an inspector who had tortured him 25 years earlier, feels like it might be about grace and catharsis, but the final mood is that of injustice that was never redressed – a sense of frustration that the tormentor got off too easily (even if he spent his last few months wracked by disease and pain) while the victim spent decades in a state of limbo.

“I did not know where to direct my anger,” a frustrated narrator tells us, and this is true for so many of the victims in these stories. Grand-sounding ideas like forgiveness or benediction hold no meaning in a place where destroyed lives cannot be un-destroyed, and there is no closure even after death. (One passage is in a ghost’s voice.)

The Night of Broken Glass is terrific as a concept, with its many narrative detours and collisions – no safety nets for the reader, no familiar structures we can cling to. In execution, though, this book blows hot and cold. Rather tries to do many different things, which is always admirable in a debut, but sometimes he tries too hard. Many passages are unwieldy and some of the writing is over-earnest, straining for effect. One sample among many: “Wispy white roots drank their fill until they were soggy and satiated, the water soundlessly penetrated the hearts of the soil particles, suffusing the empty spaces in between […] a multitude of trickles descending to touch my bare, twinkling toes.”

That’s a pity, because this author can do much more with less. A single, terse sentence such as “The shop filled with the gloom of humiliation” – after a story is told about a respected man being slapped by a soldier – can be more effective than paragraphs of poorly constructed ornate prose.

----------------------------

[A somewhat related post: on Vishal Bhardwaj's Haider, and a chat with Basharat Peer]

-------------------------------------------

In one of the many interconnected stories in Feroz Rather's The Night of Broken Glass , a tyrannical Army major watches Hitchcock’s Rope on TV. As the passage becomes increasingly surreal, his private reminiscences merge with scenes from the film.

Like Rope, which was about a motive-less murder, Rather's book centres on tragic, untimely deaths and destructive hubris. But unlike the film, famously made up of long takes, The Night of Broken Glass is filled with the literary equivalents of slow dissolves. One story plays alongside and informs another. Voices and perspectives change. Chronology is uncertain. Nightmare scenes are told with the lucidity of reportage, and actual incidents related as if they were nightmares. The writing is raw and vulnerable and sometimes meandering, as if to capture the rhythms of oral storytelling.

Like Rope, which was about a motive-less murder, Rather's book centres on tragic, untimely deaths and destructive hubris. But unlike the film, famously made up of long takes, The Night of Broken Glass is filled with the literary equivalents of slow dissolves. One story plays alongside and informs another. Voices and perspectives change. Chronology is uncertain. Nightmare scenes are told with the lucidity of reportage, and actual incidents related as if they were nightmares. The writing is raw and vulnerable and sometimes meandering, as if to capture the rhythms of oral storytelling.All this adds up to an unusual, restless narrative that looks at the violence in Kashmir mainly through the experiences of young people who smoke Revolution cigarettes, wear Liberty shoes and strive for “Azaadi”, usually to no avail. A boy makes a rosary out of bullet shells collected by his father. A journalist writes a resignation letter to her boss, denouncing a profession made up of complacent, power-drunk men. (Later, the boss gets to speak to us too.) A story where a man finds himself looking after a cancer-ridden shell of a body, belonging to an inspector who had tortured him 25 years earlier, feels like it might be about grace and catharsis, but the final mood is that of injustice that was never redressed – a sense of frustration that the tormentor got off too easily (even if he spent his last few months wracked by disease and pain) while the victim spent decades in a state of limbo.

“I did not know where to direct my anger,” a frustrated narrator tells us, and this is true for so many of the victims in these stories. Grand-sounding ideas like forgiveness or benediction hold no meaning in a place where destroyed lives cannot be un-destroyed, and there is no closure even after death. (One passage is in a ghost’s voice.)

The Night of Broken Glass is terrific as a concept, with its many narrative detours and collisions – no safety nets for the reader, no familiar structures we can cling to. In execution, though, this book blows hot and cold. Rather tries to do many different things, which is always admirable in a debut, but sometimes he tries too hard. Many passages are unwieldy and some of the writing is over-earnest, straining for effect. One sample among many: “Wispy white roots drank their fill until they were soggy and satiated, the water soundlessly penetrated the hearts of the soil particles, suffusing the empty spaces in between […] a multitude of trickles descending to touch my bare, twinkling toes.”

That’s a pity, because this author can do much more with less. A single, terse sentence such as “The shop filled with the gloom of humiliation” – after a story is told about a respected man being slapped by a soldier – can be more effective than paragraphs of poorly constructed ornate prose.

----------------------------

[A somewhat related post: on Vishal Bhardwaj's Haider, and a chat with Basharat Peer]

Published on August 01, 2018 19:49

July 30, 2018

Barsaat mein… some of my favourite rainy-day scenes

Did this piece for Mint Lounge’s monsoon special – a little ode to some beloved Hindi-film rain SEQUENCES (not just rain songs)

------------------------------------

One of Hindi cinema’s most indelible monsoon scenes – Nargis and Raj Kapoor holding a single umbrella between them, singing “Pyaar Hua Ikraar Hua” in Shree 420 (1955) – has a new resonance these days, given the fuss over the Sanjay Dutt biopic Sanju. When Nargis sings “Main na rahoongi, tum na rahoge, phir bhi rahengi nishaaniyan (We won’t be around forever, but the tokens of our love will remain)”, we see the two-year-old Rishi Kapoor walking down a drenched street with his siblings. Could any of the people involved in this shoot have imagined that six decades later, the son of that infant (Ranbir Kapoor) would play Nargis’s “baba” in a hagiographical film?

One of Hindi cinema’s most indelible monsoon scenes – Nargis and Raj Kapoor holding a single umbrella between them, singing “Pyaar Hua Ikraar Hua” in Shree 420 (1955) – has a new resonance these days, given the fuss over the Sanjay Dutt biopic Sanju. When Nargis sings “Main na rahoongi, tum na rahoge, phir bhi rahengi nishaaniyan (We won’t be around forever, but the tokens of our love will remain)”, we see the two-year-old Rishi Kapoor walking down a drenched street with his siblings. Could any of the people involved in this shoot have imagined that six decades later, the son of that infant (Ranbir Kapoor) would play Nargis’s “baba” in a hagiographical film?

But while we know that actors can pass their nishaaniyan down to us in the shape of star-children and star-grandchildren, the Shree 420 scene is noteworthy in another way. How unusual it is for a star couple, at the peak of their popularity, to pause and remind us – midway through a passionate song about first love – that nothing is eternal; that they will fade away and be supplanted.

But while we know that actors can pass their nishaaniyan down to us in the shape of star-children and star-grandchildren, the Shree 420 scene is noteworthy in another way. How unusual it is for a star couple, at the peak of their popularity, to pause and remind us – midway through a passionate song about first love – that nothing is eternal; that they will fade away and be supplanted.

There could be something about rain that encourages this manner of philosophizing. A few years ago, Shyam Benegal (not himself a director you’d associate with “monsoon songs”) told me about an educational TV series he had worked on for UNICEF in the early 1970s, combining science with folk tales. One story about rainwater harvesting had an explanation of why water bodies disappear in extreme summer. “We started with a lake,” Benegal said in a charmingly staccato tone, “It looks up. Falls in love with the sky. Burns with love. Evaporates into a cloud. Goes looking for the sky. Does not find the sky. Weeps, becomes rain. And the cycle of life continues.”

Rain as regeneration: washing away the old, heralding the new. Such depictions occur in many types of film songs, such as the ones where villagers look to the skies, waiting anxiously for the “weeping” cloud that will bring fertility and future generations of crops. Interestingly, two of the most iconic sequences in this vein, shot fifty years apart – “Hariyala Sawan Dhol Bajaata” in Do Bigha Zamin (1953) and “Ghanan Ghanan” in Lagaan (2001) – don’t show us any precipitation. In a literal, visual sense, these aren’t “rain songs”, but in a spiritual sense they are: the scenes are soaked with the anticipation of the monsoon and its joyful, life-giving effects.

Then there is the romantic rain song, which seems like a cliché but operates in many modes and meters. We have the giddy, light-hearted sort (watch Aamir Khan, umbrella in tow, chanelling Gene Kelly as he serenades Neelam in Afsana Pyaar Ka’s “Tip Tip Tip Tip Baarish”) as well as the intense version that uses the raging elements as a metaphor for unrest in the heart. “Baahar bhi toofan, andar bhi toofan (There is a storm both outside and inside),” sing Amrita Singh and Sunny Deol in “Baadal Yun Garajta Hai” in Betaab – the scene articulates the elation and fear of young love, while also supplying a pretext for the lovers to cling to each other when the sound of thunder scares them.

Everyone knows about the sensual rain song, with the wet heroine catering to the male gaze, but the same sort of scene can offer something more complex: watch how Mr India – a lovely children’s film with Sridevi playing a desi Lois Lane to the titular superhero – takes a right turn into grown-up territory when the uninhibited heroine sways to “Kaate nahin kat te”. (For many of us kids watching in the mid-80s, this scene was a jaw-dropping introduction – not too common in the mainstream films of the time – to the possibility of the sexually desirous woman.)

Everyone knows about the sensual rain song, with the wet heroine catering to the male gaze, but the same sort of scene can offer something more complex: watch how Mr India – a lovely children’s film with Sridevi playing a desi Lois Lane to the titular superhero – takes a right turn into grown-up territory when the uninhibited heroine sways to “Kaate nahin kat te”. (For many of us kids watching in the mid-80s, this scene was a jaw-dropping introduction – not too common in the mainstream films of the time – to the possibility of the sexually desirous woman.)

There are the tragic love songs too: the ones that have a silver lining (in Chandni’s “Lagi Aaj Saawan Ki Phir Woh Ghadi Hai”, Vinod Khanna experiences both sad remembrance for a lost love and hope for the future) and the ones that don’t – the title song of Barsaat plays in the film’s last scene, as a young man, repentant much too late, lights the funeral pyre of the woman whom he had wronged.

But my all-time favourite rain sequence is probably the location-shot one in Manzil (1979), where Ajay (Amitabh Bachchan) and Aruna (Moushumi Chatterjee) splash through south Bombay’s monsoon-lashed roads and maidans while the second, female version of “Rim Jhim Gire Saawan” plays on the soundtrack.

Stunning as this scene – shot by KK Mahajan – is on its own terms, it also makes for a fine visual contrast with the earlier, more somber version of the song, which we saw at the film’s beginning when Ajay sings for an audience in a room. That scene was poised, tranquil, controlled (dare one say “climate-controlled”?), while the outdoor one is spontaneous, exhilarating, improvised. In a story about a man whose vaulting ambition leads him to bend ethical codes and then repent, the difference between “Rim Jhim” indoors and outdoors is a bit like the gap between theory and lived experience – sitting in one place and pontificating about life versus going out on the streets and facing it in its gusty, splashy, unpredictable madness.

------------------------------------

One of Hindi cinema’s most indelible monsoon scenes – Nargis and Raj Kapoor holding a single umbrella between them, singing “Pyaar Hua Ikraar Hua” in Shree 420 (1955) – has a new resonance these days, given the fuss over the Sanjay Dutt biopic Sanju. When Nargis sings “Main na rahoongi, tum na rahoge, phir bhi rahengi nishaaniyan (We won’t be around forever, but the tokens of our love will remain)”, we see the two-year-old Rishi Kapoor walking down a drenched street with his siblings. Could any of the people involved in this shoot have imagined that six decades later, the son of that infant (Ranbir Kapoor) would play Nargis’s “baba” in a hagiographical film?

One of Hindi cinema’s most indelible monsoon scenes – Nargis and Raj Kapoor holding a single umbrella between them, singing “Pyaar Hua Ikraar Hua” in Shree 420 (1955) – has a new resonance these days, given the fuss over the Sanjay Dutt biopic Sanju. When Nargis sings “Main na rahoongi, tum na rahoge, phir bhi rahengi nishaaniyan (We won’t be around forever, but the tokens of our love will remain)”, we see the two-year-old Rishi Kapoor walking down a drenched street with his siblings. Could any of the people involved in this shoot have imagined that six decades later, the son of that infant (Ranbir Kapoor) would play Nargis’s “baba” in a hagiographical film? But while we know that actors can pass their nishaaniyan down to us in the shape of star-children and star-grandchildren, the Shree 420 scene is noteworthy in another way. How unusual it is for a star couple, at the peak of their popularity, to pause and remind us – midway through a passionate song about first love – that nothing is eternal; that they will fade away and be supplanted.

But while we know that actors can pass their nishaaniyan down to us in the shape of star-children and star-grandchildren, the Shree 420 scene is noteworthy in another way. How unusual it is for a star couple, at the peak of their popularity, to pause and remind us – midway through a passionate song about first love – that nothing is eternal; that they will fade away and be supplanted. There could be something about rain that encourages this manner of philosophizing. A few years ago, Shyam Benegal (not himself a director you’d associate with “monsoon songs”) told me about an educational TV series he had worked on for UNICEF in the early 1970s, combining science with folk tales. One story about rainwater harvesting had an explanation of why water bodies disappear in extreme summer. “We started with a lake,” Benegal said in a charmingly staccato tone, “It looks up. Falls in love with the sky. Burns with love. Evaporates into a cloud. Goes looking for the sky. Does not find the sky. Weeps, becomes rain. And the cycle of life continues.”

Rain as regeneration: washing away the old, heralding the new. Such depictions occur in many types of film songs, such as the ones where villagers look to the skies, waiting anxiously for the “weeping” cloud that will bring fertility and future generations of crops. Interestingly, two of the most iconic sequences in this vein, shot fifty years apart – “Hariyala Sawan Dhol Bajaata” in Do Bigha Zamin (1953) and “Ghanan Ghanan” in Lagaan (2001) – don’t show us any precipitation. In a literal, visual sense, these aren’t “rain songs”, but in a spiritual sense they are: the scenes are soaked with the anticipation of the monsoon and its joyful, life-giving effects.