Jai Arjun Singh's Blog, page 34

February 11, 2019

Flashback series – why you should watch Waqt (1965)

[the third entry in my Film Companion series. From the cosy, black-and-white Mem Didi in my last column to the lavishly mounted and colour-drenched Waqt – it’s like going from a low-budget B-movie to a Cecil B DeMille epic. But perhaps the better Hollywood analogy would be with a 1950s Douglas Sirk melodrama – glossy, opulent but capable of shifting between the grand moment and the intimate one]

[the third entry in my Film Companion series. From the cosy, black-and-white Mem Didi in my last column to the lavishly mounted and colour-drenched Waqt – it’s like going from a low-budget B-movie to a Cecil B DeMille epic. But perhaps the better Hollywood analogy would be with a 1950s Douglas Sirk melodrama – glossy, opulent but capable of shifting between the grand moment and the intimate one] ---------------------------

Title: Waqt

Director: Yash Chopra

Year: 1965

Cast: Sunil Dutt, Raaj Kumar, Sadhana, Sharmila Tagore, Shashi Kapoor, Balraj Sahni, Achala Sachdev, Rehman

Why you should watch it:

Because it’s a near-perfect summary of the “masala” film before the term was commonly used

Here are my dominant childhood memories of watching Waqt on TV:

*A middle-aged couple with three children – conservatively dressed mummy-ji, daddy-ji types – exchange lovelorn glances as the man sings to his wife at a mehfil of friends and family,

*An earthquake strikes just as a businessman, flush on material success, boasts about his fortunes,

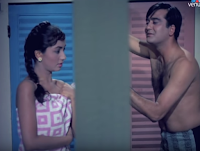

*In a daring-for-the-time scene, set in a swimming-pool changing room, two young lovers get out of their wet costumes, press against the wall separating them and whisper sweet nothings to each other,

*Swanky convertibles race each other in a sequence which offers the grand conceit that an Indian landscape – with potholes, random construction work and vegetable sellers in the middle of the road – could be a setting for this sort of thrill,

*Swanky convertibles race each other in a sequence which offers the grand conceit that an Indian landscape – with potholes, random construction work and vegetable sellers in the middle of the road – could be a setting for this sort of thrill, *During a trial, a man opens a cupboard to demonstrate an action to the court, only to have a life-sized dummy fall on him from inside.

These and many other setpieces make up this sprawling work, a progenitor of the lost-and-found multi-starrer of the 1970s (Yaadon ki Baarat, Amar Akbar Anthony), as well as a lovely-looking film packed with glamorous people conducting romances, AND a courtroom drama built around a murder. Can we say “masala”? That term has been over-used in descriptions of mainstream Hindi cinema, but rarely has it applied so well to a film as to this one.

For the stars, the gloss and the clothes

This was Yash Chopra’s first colour film, and it anticipates the lush vistas and romances of films like Kabhi Kabhie, Silsila and Chandni. In her memoir, the celebrated costume designer Bhanu Athaiya notes how invigorating it was to work with so many different character types, situations and settings. The outfits worn by Sadhana and Sharmila Tagore became so popular, she says, that girls in Delhi bought movie tickets for their tailors so they could see the designs and replicate them. (“We introduced the churidar pyjama and sleeveless fitted kurtas with a side band that brought complete attention to the body form.”)

Given this, the actors were at an advantage from the start. Raaj Kumar is always an acquired taste (and his performance as the oldest of the three separated brothers involves some eccentric choices), but even he manages to look suave here. There is an

unusually energetic, fast-speaking performance by Sunil Dutt as the garrulous Ravi, and the more obviously glamorous stars – Sadhana, Sharmila Tagore, Shashi Kapoor – look terrific. (Kapoor has a one-dimensional role, but the line “mere paas ma hai” would fit his character here as well as it did in Chopra’s Deewaar 10 years later – though in Waqt, he is the one named Vijay!)

unusually energetic, fast-speaking performance by Sunil Dutt as the garrulous Ravi, and the more obviously glamorous stars – Sadhana, Sharmila Tagore, Shashi Kapoor – look terrific. (Kapoor has a one-dimensional role, but the line “mere paas ma hai” would fit his character here as well as it did in Chopra’s Deewaar 10 years later – though in Waqt, he is the one named Vijay!) For the way in which a complicated narrative is woven together, and the use of the “adalat” as an allegorical place where justice is served on multiple fronts

The film’s arc moves from a genteel if aspirational world represented by Lala Kedarnath (Sahni) and his wife to a more modern space: sleek cars, jewel thieves breaking into high society. Things get a bit slack for a while as relationships are formed and a love triangle collapses, but the pace picks up in the final third; the many narrative strands are masterfully brought together in the “Aage bhi jaane na tu” song sequence – and finally, in the trial.

With all the hyper-realism of today’s cinema, contemporary viewers have become sheepish about – or outright dismissive of – the grand courtroom scene of yore, which is a pity. What a cast of actors and characters comes together in Waqt’s court scene, and how many small and big dramas play out!

Incidentally one of the least-mentioned members of the large cast is the veteran Motilal, as the prosecutor in the climax. Though long past his heyday here, Motilal was once regarded, along with Ashok Kumar and Balraj Sahni, among the first exponents of “naturalistic” (as opposed to theatrical) Hindi-film acting. Which means that watching him and Sahni briefly share screen space here is a historical document of sorts.

For a reminder that even in the good old days, rich Indians were happy to manipulate their poor drivers into helping cover up their crimes

Decades before Aravind Adiga wrote The White Tiger, or certain real-life cases came to public notice before being hushed up, here is Chinoy Seth (Rehman), all elegant largesse when it comes to mundane matters, but showing his fangs when big things are at stake. “Duty din ki ho ya raat ki, inkaar nahin karoge,” he tells his soon-to-be-driver at their first meeting. Things get worse for the poor employee, who will soon understand that the “raat” in that sentence could also mean a nighttime of the soul.

Decades before Aravind Adiga wrote The White Tiger, or certain real-life cases came to public notice before being hushed up, here is Chinoy Seth (Rehman), all elegant largesse when it comes to mundane matters, but showing his fangs when big things are at stake. “Duty din ki ho ya raat ki, inkaar nahin karoge,” he tells his soon-to-be-driver at their first meeting. Things get worse for the poor employee, who will soon understand that the “raat” in that sentence could also mean a nighttime of the soul. For being blasé about the little awkwardnesses that come out of dramatic family reunions

Raju ends up being big brother-in-law to the woman he was trying to woo for much of the film; Ravi must deal with the fact that his adoptive sister and his real brother are in love and getting married.

For the snarling but hapless Madan Puri

Here is one of Hindi cinema’s most ineffectual bad men. The stocky Puri, always dressed as if he left his house uncertain whether to commit a bank robbery or attend a cocktail party, shrieks in anger and pulls out a sharp knife whenever something annoys him – but he never seems able to do anything useful with the weapon, and is swiftly overpowered (even by the un-muscular Rehman). Time may heal all wounds, as the film’s title and screenplay keep reminding us, but as this unfortunate villain discovers, it also wounds all heels.

[Earlier Flashback pieces are here]

Published on February 11, 2019 19:53

February 8, 2019

That tingling sensation (or, Attack of the Killer Chairs)

[My latest column for The Hindu is about how 4D can turn a regular movie scene into massage therapy... or whiplash]

[My latest column for The Hindu is about how 4D can turn a regular movie scene into massage therapy... or whiplash]----------------

As discussed before in this space, many factors determine the effect a movie sequence has on a viewer: your mood on the day, your emotional connect with the setting, the degree to which you relate with a character. But as a recent experience showed me, a scene’s impact may also hinge on whether the chair you are sitting in is violently shaking.

Going in to watch Damien Chazelle’s First Man, I had heard that the opening scene – in which Neil Armstrong narrowly escapes a rocket-plane accident in 1961 – was a marvelous bit of filmmaking, both for the claustrophobia-inducing sense that we are in the shuddering cockpit with Armstrong, and for the pre-echoing of things to come: we know that this man will walk on the Moon years later, after an inter-space journey much more complicated and fraught than his current adventure.

Unfortunately, I barely registered what was happening to Neil, because I was worried about the state of my own vitamin D-deficient bones. Without realizing it, I had bought tickets to a 4DX show. This apparently means the sort of immersive experience where your chair performs calisthenics each time something bumpy (like a plane ride, or an astronauts’ training session, or maybe just two people dancing the salsa) happens onscreen. Midway through, my friend was thanking her stars that she hadn’t brought her father along as initially planned. To reference the titles of other Chazelle films, the experience was less la-la-land and more whiplash.

****

So I couldn’t fully appreciate First Man – though I made up for it by listening to the beautiful Justin Hurwitz soundtrack at home, sitting on my boringly stationary sofa. And yet, much as I would have liked to watch the film without all these accoutrements, I was also left with the feeling that the 4D could have been more imaginative.

All we got was chairs shaking every few minutes, and on one occasion a small quantity of cool vaporous liquid sprayed at us from the side. (I forget now what was happening in the film to necessitate this: did Neil’s miffed wife throw a glass of wine in his face?) There were so many other unexplored possibilities. For instance, in the climax, when our hero makes it to his zero-gravity destination, our chairs could have detached themselves from their moorings and floated about the large hall with us in them, like versions of the Star Child in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

It is also exciting to think about what this technique may accomplish for Indian cinema. When we stand up for the national anthem before a screening, or watch an Akshay Kumar film (or stand up when the national anthem inevitably plays during an Akshay Kumar film), perhaps nozzles will spit itchy tricoloured powder into our eyes, making us feel even more patriotic than we already were? Or imagine a show of Tumbbad – a cautionary horror story about greed – where gold coins are sprinkled into the audience; when we bend to collect them, a neon-lit, battery-operated version of the demon Hastar snarls at us from under our seats.

Much can also be done with 3D holograms, which are relatively easy to project out of a screen in such a way that the audience feels the image is flying at them. That scene in Andha Dhun where evil Tabu defenestrates an old woman? How much more thrilling it would be if, at the moment of the assault, a spectral Mrs D’Sa were to appear shrieking and flailing over our heads.

*****

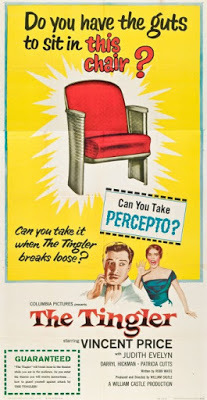

Notwithstanding our conceit that such bold innovations are the prerogative of our own age, none of this is new. As far back as 1959, the American producer-director William Castle used a vibrating device – the Percepto – on selected chairs during the screening of his B-horror film The Tingler; the device came into effect during the film’s creepiest scenes, which involved a wriggling creature attacking its victims’ spines.

My favourite part of that story, though, is that the Percepto was accidentally used during a tearful scene in the Audrey Hepburn-starrer The Nun’s Story (a film as austere and high-minded as its title sounds). In the Netflix age, I feel we could do with such mix-and-matches to enliven our theatre experience. Imagine: you’re on the last scene of Badhaai Ho, Neena Gupta’s baby has made its long-awaited appearance, and instead of a hologram of a gurgling little cherub dropping virtual flowers and glitter and baby spittle on our heads, the screen dispenses a tired-looking Amitabh Bachchan in pirate regalia, waving his sword feebly and calling out to his bird.

If that won’t get lazy viewers away from their laptops and into the halls, nothing will.

[Earlier Hindu columns are here]

Published on February 08, 2019 03:21

February 1, 2019

The flashback series: why you should watch Mem Didi (1961)

[The second in my 1950s-1960s series for Film Companion – this one about a very charming film that I have also written about in my Hrishikesh Mukherjee book. The first piece, on Kala Bazaar, is here]

-----------------------------

Title: Mem Didi

Title: Mem Didi

Director: Hrishikesh Mukherjee

Year: 1961

Cast: Lalita Pawar, David, Jayant, Tanuja, Kaysi Mehra

Why you should watch it:

For the beautiful chemistry between three elderly character actors

It is generally agreed that Hindi cinema is currently in a very good phase for the “character role” – such as the middle-aged parents played by Neena Gupta and Gajraj Rao in Badhaai Ho, who would rarely if ever have been placed front and centre in a mainstream film of an earlier age.

But consider Mem Didi. This film has a bubbly romantic track all right, featuring two appealing if inexperienced young actors: the 17-year-old Tanuja and the Aamir Khan-lookalike Kaysi Mehra. In the second half, the narrative focuses on the obstacles facing the happiness of these lovebirds; they get disproportionate space on posters and DVD covers too. However, the real centerpiece of this film, and the single most compelling thing about it, is the marvelous interplay between three unglamorous character actors who were better known for small stock parts in movies of the time. David Abraham, Jayant, and Lalita Pawar bring credibility to every scene they are in, and are responsible for making the village in which much of the story is set feel like a real, lived-in place.

A brief synopsis. Bahadur Singh (David) and Sher Khan (Jayant) are two lovable rogues who exercise a benevolent dominance over their community, but meet their match when Rosy (Pawar), swinging her umbrella and fists, moves in and demonstrates that “didi-giri” can trump “dada-giri”. The initial clash of wills gives way to comradeship, and soon the two men become godfather figures to Rosy’s teenage foster daughter Rita (Tanuja), who is in a hill-station boarding school.

A brief synopsis. Bahadur Singh (David) and Sher Khan (Jayant) are two lovable rogues who exercise a benevolent dominance over their community, but meet their match when Rosy (Pawar), swinging her umbrella and fists, moves in and demonstrates that “didi-giri” can trump “dada-giri”. The initial clash of wills gives way to comradeship, and soon the two men become godfather figures to Rosy’s teenage foster daughter Rita (Tanuja), who is in a hill-station boarding school.

For being the first truly lighthearted and whimsical Hrishikesh Mukherjee film – pointing to the way ahead

This was Mukherjee’s fourth film as director, made when he was starting to come into his own, breaking out of the shadow of his mentor Bimal Roy and his close friend Raj Kapoor. Hrishi-da’s directorial debut Musafir (1957) was made largely with Roy’s crew; his second, Anari (1959), was shot at RK Studios and feels like a Raj Kapoor-helmed film, a lighter version of Awaara perhaps. It was with the third and fourth films, Anuradha and Mem Didi respectively, that Hrishi-da truly began his own innings. And of all these, Mem Didi is the first film where the dominant quality was breeziness – with comedy getting the upper hand in the comedy-drama jugalbandhi that would persist throughout his long career.

This is not to say that Mem Didi doesn’t have a few maudlin moments – it does. But given that the basic plot involves a poor old woman toiling away to get her child through school (now there’s a trope from movie melodrama if there ever was one!), it’s remarkable how the film steers clear of prolonged sentimentalism and always finds a way to veer back to the chirpy or the idiosyncratic.

And again, much of the credit goes to the performances of the three senior actors. Casting the hard-edged Lalilta Pawar in a role like this was a master touch: much like Thelma Ritter in the Hollywood of the 1950s, Pawar had the ability to undercut a sentimentally written scene with her dry personality. Even when Rosy is weeping or fretting, you know a zinger or a sharp glance is just around the corner.

Similarly, having the stout and genial David – of Bene Israeli background – play a proud Rajput would never have made sense on paper, but it works brilliantly in practice. And the big burly Jayant, with his Pathan accent, might remind you of Baloo the bear shuffling around. With two other actors in these roles, the characters might have come across as mean or nasty (in scenes like the one where Bahadur flexes his muscles to intimidate a doctor, or where they coolly change the time on a restaurant clock after arriving late for dinner) – but these two are consistently endearing. Some of the looks they exchange – after their first, emasculating encounter with Rosy, for instance – are worth the price of admission. Watch how they go in the blink of an eye from strutting around like wannabe Samurais in a Kurosawa film to walking away sheepishly, with hands behind their back, like errant schoolboys, after being chastened.

Similarly, having the stout and genial David – of Bene Israeli background – play a proud Rajput would never have made sense on paper, but it works brilliantly in practice. And the big burly Jayant, with his Pathan accent, might remind you of Baloo the bear shuffling around. With two other actors in these roles, the characters might have come across as mean or nasty (in scenes like the one where Bahadur flexes his muscles to intimidate a doctor, or where they coolly change the time on a restaurant clock after arriving late for dinner) – but these two are consistently endearing. Some of the looks they exchange – after their first, emasculating encounter with Rosy, for instance – are worth the price of admission. Watch how they go in the blink of an eye from strutting around like wannabe Samurais in a Kurosawa film to walking away sheepishly, with hands behind their back, like errant schoolboys, after being chastened.

In fact, in the early scenes, the film’s plot often plays second fiddle to Bahadur and Sher Khan’s desultory conversations. There are many casual little moments, which exist almost for their own sake – or to create a certain mood – rather than to take the narrative forward.

For Tanuja, singing and dancing with a dog

In Anari, Raj Kapoor briefly cavorts with a street dog while singing “Kisi Ki Muskurahaton Pe”. In Mem Didi, Hrishikesh Mukherjee – so well-known for being a canine lover that a 1970s magazine profile of him was titled “Hrishi-da in a house full of bitches”! – takes the theme a few steps forward by picturizing a song sequence that is entirely built around a conversation between Rita and a village stray. “Beta, wah wah wah!” she sings (you’ll find the words listed as “Beta, woof woof woof!” in some places), while the dog adds its own howl to the chorus and then prances around holding an umbrella.

In Anari, Raj Kapoor briefly cavorts with a street dog while singing “Kisi Ki Muskurahaton Pe”. In Mem Didi, Hrishikesh Mukherjee – so well-known for being a canine lover that a 1970s magazine profile of him was titled “Hrishi-da in a house full of bitches”! – takes the theme a few steps forward by picturizing a song sequence that is entirely built around a conversation between Rita and a village stray. “Beta, wah wah wah!” she sings (you’ll find the words listed as “Beta, woof woof woof!” in some places), while the dog adds its own howl to the chorus and then prances around holding an umbrella.

It’s a lovely, spontaneous little moment. It’s also one of the few times in the film that the pretty young heroine gets to be as funny and as cool as the old folk.

------------------------------

Trivia: Mem Didi was loosely based on Frank Capra’s 1933 film Lady for a Day, itself taken from a Depression-era Damon Runyon story. Coincidentally, Capra remade Lady for a Day as A Pocketful of Miracles in 1961 – the film was released just a few months after Mem Didi. (And to extend the remake theme, Hrishikesh Mukherjee remade Mem Didi in 1983 as Accha Bura, with Amjad Khan playing the role his father Jayant had played in the original.)

-----------------------------

Title: Mem Didi

Title: Mem DidiDirector: Hrishikesh Mukherjee

Year: 1961

Cast: Lalita Pawar, David, Jayant, Tanuja, Kaysi Mehra

Why you should watch it:

For the beautiful chemistry between three elderly character actors

It is generally agreed that Hindi cinema is currently in a very good phase for the “character role” – such as the middle-aged parents played by Neena Gupta and Gajraj Rao in Badhaai Ho, who would rarely if ever have been placed front and centre in a mainstream film of an earlier age.

But consider Mem Didi. This film has a bubbly romantic track all right, featuring two appealing if inexperienced young actors: the 17-year-old Tanuja and the Aamir Khan-lookalike Kaysi Mehra. In the second half, the narrative focuses on the obstacles facing the happiness of these lovebirds; they get disproportionate space on posters and DVD covers too. However, the real centerpiece of this film, and the single most compelling thing about it, is the marvelous interplay between three unglamorous character actors who were better known for small stock parts in movies of the time. David Abraham, Jayant, and Lalita Pawar bring credibility to every scene they are in, and are responsible for making the village in which much of the story is set feel like a real, lived-in place.

A brief synopsis. Bahadur Singh (David) and Sher Khan (Jayant) are two lovable rogues who exercise a benevolent dominance over their community, but meet their match when Rosy (Pawar), swinging her umbrella and fists, moves in and demonstrates that “didi-giri” can trump “dada-giri”. The initial clash of wills gives way to comradeship, and soon the two men become godfather figures to Rosy’s teenage foster daughter Rita (Tanuja), who is in a hill-station boarding school.

A brief synopsis. Bahadur Singh (David) and Sher Khan (Jayant) are two lovable rogues who exercise a benevolent dominance over their community, but meet their match when Rosy (Pawar), swinging her umbrella and fists, moves in and demonstrates that “didi-giri” can trump “dada-giri”. The initial clash of wills gives way to comradeship, and soon the two men become godfather figures to Rosy’s teenage foster daughter Rita (Tanuja), who is in a hill-station boarding school.For being the first truly lighthearted and whimsical Hrishikesh Mukherjee film – pointing to the way ahead

This was Mukherjee’s fourth film as director, made when he was starting to come into his own, breaking out of the shadow of his mentor Bimal Roy and his close friend Raj Kapoor. Hrishi-da’s directorial debut Musafir (1957) was made largely with Roy’s crew; his second, Anari (1959), was shot at RK Studios and feels like a Raj Kapoor-helmed film, a lighter version of Awaara perhaps. It was with the third and fourth films, Anuradha and Mem Didi respectively, that Hrishi-da truly began his own innings. And of all these, Mem Didi is the first film where the dominant quality was breeziness – with comedy getting the upper hand in the comedy-drama jugalbandhi that would persist throughout his long career.

This is not to say that Mem Didi doesn’t have a few maudlin moments – it does. But given that the basic plot involves a poor old woman toiling away to get her child through school (now there’s a trope from movie melodrama if there ever was one!), it’s remarkable how the film steers clear of prolonged sentimentalism and always finds a way to veer back to the chirpy or the idiosyncratic.

And again, much of the credit goes to the performances of the three senior actors. Casting the hard-edged Lalilta Pawar in a role like this was a master touch: much like Thelma Ritter in the Hollywood of the 1950s, Pawar had the ability to undercut a sentimentally written scene with her dry personality. Even when Rosy is weeping or fretting, you know a zinger or a sharp glance is just around the corner.

Similarly, having the stout and genial David – of Bene Israeli background – play a proud Rajput would never have made sense on paper, but it works brilliantly in practice. And the big burly Jayant, with his Pathan accent, might remind you of Baloo the bear shuffling around. With two other actors in these roles, the characters might have come across as mean or nasty (in scenes like the one where Bahadur flexes his muscles to intimidate a doctor, or where they coolly change the time on a restaurant clock after arriving late for dinner) – but these two are consistently endearing. Some of the looks they exchange – after their first, emasculating encounter with Rosy, for instance – are worth the price of admission. Watch how they go in the blink of an eye from strutting around like wannabe Samurais in a Kurosawa film to walking away sheepishly, with hands behind their back, like errant schoolboys, after being chastened.

Similarly, having the stout and genial David – of Bene Israeli background – play a proud Rajput would never have made sense on paper, but it works brilliantly in practice. And the big burly Jayant, with his Pathan accent, might remind you of Baloo the bear shuffling around. With two other actors in these roles, the characters might have come across as mean or nasty (in scenes like the one where Bahadur flexes his muscles to intimidate a doctor, or where they coolly change the time on a restaurant clock after arriving late for dinner) – but these two are consistently endearing. Some of the looks they exchange – after their first, emasculating encounter with Rosy, for instance – are worth the price of admission. Watch how they go in the blink of an eye from strutting around like wannabe Samurais in a Kurosawa film to walking away sheepishly, with hands behind their back, like errant schoolboys, after being chastened.In fact, in the early scenes, the film’s plot often plays second fiddle to Bahadur and Sher Khan’s desultory conversations. There are many casual little moments, which exist almost for their own sake – or to create a certain mood – rather than to take the narrative forward.

For Tanuja, singing and dancing with a dog

In Anari, Raj Kapoor briefly cavorts with a street dog while singing “Kisi Ki Muskurahaton Pe”. In Mem Didi, Hrishikesh Mukherjee – so well-known for being a canine lover that a 1970s magazine profile of him was titled “Hrishi-da in a house full of bitches”! – takes the theme a few steps forward by picturizing a song sequence that is entirely built around a conversation between Rita and a village stray. “Beta, wah wah wah!” she sings (you’ll find the words listed as “Beta, woof woof woof!” in some places), while the dog adds its own howl to the chorus and then prances around holding an umbrella.

In Anari, Raj Kapoor briefly cavorts with a street dog while singing “Kisi Ki Muskurahaton Pe”. In Mem Didi, Hrishikesh Mukherjee – so well-known for being a canine lover that a 1970s magazine profile of him was titled “Hrishi-da in a house full of bitches”! – takes the theme a few steps forward by picturizing a song sequence that is entirely built around a conversation between Rita and a village stray. “Beta, wah wah wah!” she sings (you’ll find the words listed as “Beta, woof woof woof!” in some places), while the dog adds its own howl to the chorus and then prances around holding an umbrella.It’s a lovely, spontaneous little moment. It’s also one of the few times in the film that the pretty young heroine gets to be as funny and as cool as the old folk.

------------------------------

Trivia: Mem Didi was loosely based on Frank Capra’s 1933 film Lady for a Day, itself taken from a Depression-era Damon Runyon story. Coincidentally, Capra remade Lady for a Day as A Pocketful of Miracles in 1961 – the film was released just a few months after Mem Didi. (And to extend the remake theme, Hrishikesh Mukherjee remade Mem Didi in 1983 as Accha Bura, with Amjad Khan playing the role his father Jayant had played in the original.)

Published on February 01, 2019 23:46

January 27, 2019

The library of weird ailments

[Did this short review for India Today – about Vikram Paralkar’s The Afflictions, a novel (if that’s the right word for it) about a library of very strange, and sometimes recognizable, ailments]

-------------------------------

What a strange and compelling book this is. It’s easy to call it Borgesian (especially since one of the epigraphs is from Borges’s The Library of Babel), but that doesn’t begin to explain its effect. Nor is it a novel in the sense that most of us are used to – a narrative with a clear beginning, middle and end. Instead, physician-scientist Vikram Paralkar offers us glimpses from the precious Encyclopaedia Medicinae, housed in the Central Library in an unspecified time and place – though the setting and the style of the writing appears medieval.

What a strange and compelling book this is. It’s easy to call it Borgesian (especially since one of the epigraphs is from Borges’s The Library of Babel), but that doesn’t begin to explain its effect. Nor is it a novel in the sense that most of us are used to – a narrative with a clear beginning, middle and end. Instead, physician-scientist Vikram Paralkar offers us glimpses from the precious Encyclopaedia Medicinae, housed in the Central Library in an unspecified time and place – though the setting and the style of the writing appears medieval.Using a very short framing story about a man named Maximo being shown around by the head librarian, the bulk of Paralkar’s book is simply a chronicle of some of the ailments recorded in the encyclopaedia. Grotesque, mystical, these are clearly imagined afflictions – or are they? Some are clearly otherworldly: in “Osteitis deformans preciosa”, the invalid’s bones keep folding back on themselves, even beyond death, until a year later a whole skeleton has been reduced to a concentrated, eyeball-sized diamond. But others are more plausible, with echoes in the human condition as we know it: blank spots in the mind, so that only fragments of certain incidents can be remembered; a disease called “Morbus geographicus” where the patient must detach himself from each place where he has just settled down, and travel to new pastures for healing. Readers familiar with the medical writings of Oliver Sacks (The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat) or VS Ramachandran (Phantoms in the Brain) may be reminded of the more unusual neurological cases discussed in those books.

Each entry is accompanied by a simple yet resonant illustration by Pia Valentinis, and the writing style is deliberately impassive, though there is some theological speculation: could Cursed Healer Syndrome, in which the sufferer takes on the disfigurements of people around him, be “a gift from the Lord”, a version of Christ suffering for others’ sins?

Each entry is accompanied by a simple yet resonant illustration by Pia Valentinis, and the writing style is deliberately impassive, though there is some theological speculation: could Cursed Healer Syndrome, in which the sufferer takes on the disfigurements of people around him, be “a gift from the Lord”, a version of Christ suffering for others’ sins?“If you read the Encyclopaedia from beginning to end,” the head librarian says, “you get the feeling that every affliction known to man is part of a single, infinite progression. Or that every disease is a different facet of a great and terrible malady.” This book is a commentary on the multi-pronged relationship between our bodies and minds – something that even today’s science is incapable of revealing too much about. There are reflections on the nature of memory, and on the creation of art: one disease causes the ears of

illiterate peasants to ring with sounds that turn out to be notes from a sophisticated musical composition; another gives its victims such powerful visions that they have no option but to express them through art, but flounder, producing only mediocre books and paintings. (How relatable this would be to the countless frustrated Salieris of the real world!)

illiterate peasants to ring with sounds that turn out to be notes from a sophisticated musical composition; another gives its victims such powerful visions that they have no option but to express them through art, but flounder, producing only mediocre books and paintings. (How relatable this would be to the countless frustrated Salieris of the real world!) And occasionally, there is something that reads like a straightforward anthropological observation. Individuals with “Empathia pathologica”, we are told, develop a crippling susceptibility to the moods of others: “It is only in absolute seclusion, far from all human contact, that they can be certain they are savouring joys or sorrows that are truly their own.” <!-- /* Font Definitions */ @font-face {font-family:"Cambria Math"; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:1; mso-generic-font-family:roman; mso-font-format:other; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:0 0 0 0 0 0;} @font-face {font-family:Calibri; panose-1:2 15 5 2 2 2 4 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1073786111 1 0 415 0;} /* Style Definitions */ p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-parent:""; margin:0cm; margin-bottom:.0001pt; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;} .MsoChpDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; mso-default-props:yes; font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;} @page WordSection1 {size:612.0pt 792.0pt; margin:72.0pt 72.0pt 72.0pt 72.0pt; mso-header-margin:36.0pt; mso-footer-margin:36.0pt; mso-paper-source:0;} div.WordSection1 {page:WordSection1;} </style><br />--></div>

Published on January 27, 2019 22:35

January 24, 2019

On Soni, a new face of the angry, two-fisted cop

[Did this piece – about the fine new film Soni, a deceptively quiet, slice-of-life narrative about the bond between two women working in the police force – for The Telegraph]

-------------------------

Amrita Pritam, or Dirty Harriet?

That was one of the thoughts in my mind as I finished watching the powerful new film Soni , now on Netflix after having been on the festival circuit for a few months. Such a juxtaposition – between one of the most elegant Indian authors of the last century and a female version of Clint Eastwood’s cop, snarling “go ahead punk, make my day” – might sound flippant or inappropriate. But the titular character in Soni – an often dejected, frustrated junior policewoman – carries versions of both those people within her.

And Ivan Ayr’s film evokes such contrasts anyway: especially for the movie-watcher who is familiar with a very different sort of “angry cop” narrative, yet finds Soni building in its quiet, unobtrusive way towards nothing dramatic like an explosion of violence, but to a reflective moment where its two protagonists talk about Amrita Pritam’s memoir Rasidi Ticket (Revenue Stamp). Soni (Geetika Vidya Ohlyan) asks her boss Kalpana (Saloni Batra) about the book’s unusual title; the latter replies that someone had once patronizingly told Amrita-ji, why write an autobiography: “your life story could be written on the back of a revenue stamp”.

And Ivan Ayr’s film evokes such contrasts anyway: especially for the movie-watcher who is familiar with a very different sort of “angry cop” narrative, yet finds Soni building in its quiet, unobtrusive way towards nothing dramatic like an explosion of violence, but to a reflective moment where its two protagonists talk about Amrita Pritam’s memoir Rasidi Ticket (Revenue Stamp). Soni (Geetika Vidya Ohlyan) asks her boss Kalpana (Saloni Batra) about the book’s unusual title; the latter replies that someone had once patronizingly told Amrita-ji, why write an autobiography: “your life story could be written on the back of a revenue stamp”.

This little anecdote comes just before Kalpana beseeches Soni to not resign and Soni replies “Ma’am, mere force mein rehne se kya pharak padega?” Though the point isn’t underlined, the implication is that any life – no matter how small or unremarkable it looks from a distance – can be full of meaning and resonance. Soni, like Amrita Pritam, can make a big difference in her field, whether she is investigating cases or operating telephones.

But is it possible for her to be a Dirty Harry as well, or a Singham, even on a minor scale?

I don’t want to over-stress the tonal difference between Soni and the more mainstream vigilante-cop film, because these are two disparate modes of filmmaking. One is the mythical, larger-than-life mode that uses escapism as therapy, centres around the figure of the two-fisted cop that goes back at least to the 1973 Zanjeer, and includes some of today's masala films like Simmba or Dabangg (the very look of those titles, with the double letters, suggesting a bulked-up machismo). On the other hand, there are the more grounded portraits of a policeman's life, on a canvas that might include an Ardh Satya (1983) as well as Devashish Makhija’s wonderful short film Taandav (2016), in which a cop played by Manoj Bajpayee gives vent to his feelings by performing a delirious, Nataraj-like dance.

But there's something else about Soni, something that goes beyond the Escapist Cop Film-Realistic Cop Film dichotomy. It has to do with gender roles and perceptions, with the subject of women occupying a space that is still seen as largely male, and sometimes requiring the aggressive, confrontational behaviour that is again perceived as being a male domain.

A question this film raises is: what if a woman cop loses her temper, or needs to use violence or profanity as a way of taking charge of an outrageous situation? What if a woman gives a ma-behen ki gaali to the man who is behaving fresh with her? What will the response be then, both from her antagonist (who might feel more entitled to express his anger) as well as from her team, who might be inclined to view her not just as a loose cannon but, more problematically, as a woman who is a loose cannon.

Instead of providing easy answers, Soni gives us a few vignettes from the lives of Soni and Kalpana – two women negotiating their different positions and hierarchies. Soni, being the subordinate and from a lower-class background, is the obvious underdog, and her personal frustrations often spill over into her work life: she burns with righteous anger, sometimes goes too far in dealing with transgressors or bullies, and has to be hauled up by her boss.

Instead of providing easy answers, Soni gives us a few vignettes from the lives of Soni and Kalpana – two women negotiating their different positions and hierarchies. Soni, being the subordinate and from a lower-class background, is the obvious underdog, and her personal frustrations often spill over into her work life: she burns with righteous anger, sometimes goes too far in dealing with transgressors or bullies, and has to be hauled up by her boss.

However, the relatively privileged Kalpana has her constraints and problems too. Pressure to start a family, to not work the night shift. She is married to a senior cop, and one senses a tension beneath the geniality of their exchanges – a tension that may stem partly from the fact that she is clearly subservient to him in more than one sense, and has to let him pull strings for her at times. In what at first seems like a bit of indulgent playfulness in the script, but later starts to make organic sense, she is frequently addressed as “Sir” by her male subordinates – perhaps the implication is that what they respect is the "manliness" of her status and designation rather than her own worth as a person.

The film expresses all this through the extraordinary, lived-in performances of Ohlyan and Batra, the use of lengthy, handheld-camera takes that capture the daily grind of their lives, and through the sound design: from the persistent hum of disheartening news coming through the radio to the noises of the city – metro construction, men boasting about their conquests – that explode in Soni’s ears as she tries to get a grip on her life. Nervy confrontations alternate with moments of grace and empathy between the two women.

It is telling, too, that near the end the explosive statement “Dil kar raha tha goli se maar doon sab ko” is said, in a quiet tone, not by a policewoman working constantly under pressure but by a 13-year-old girl who has been subjected to a humiliating prank by her (presumably male) classmates. This violent sentiment, expressed in a soft voice, echoes through the story in one form or another. It moves beneath the film’s subdued surface, so that you’re always waiting for the explosion, for the gun to go off – and it’s all the more effective when it doesn’t happen.

-------------------------

Amrita Pritam, or Dirty Harriet?

That was one of the thoughts in my mind as I finished watching the powerful new film Soni , now on Netflix after having been on the festival circuit for a few months. Such a juxtaposition – between one of the most elegant Indian authors of the last century and a female version of Clint Eastwood’s cop, snarling “go ahead punk, make my day” – might sound flippant or inappropriate. But the titular character in Soni – an often dejected, frustrated junior policewoman – carries versions of both those people within her.

And Ivan Ayr’s film evokes such contrasts anyway: especially for the movie-watcher who is familiar with a very different sort of “angry cop” narrative, yet finds Soni building in its quiet, unobtrusive way towards nothing dramatic like an explosion of violence, but to a reflective moment where its two protagonists talk about Amrita Pritam’s memoir Rasidi Ticket (Revenue Stamp). Soni (Geetika Vidya Ohlyan) asks her boss Kalpana (Saloni Batra) about the book’s unusual title; the latter replies that someone had once patronizingly told Amrita-ji, why write an autobiography: “your life story could be written on the back of a revenue stamp”.

And Ivan Ayr’s film evokes such contrasts anyway: especially for the movie-watcher who is familiar with a very different sort of “angry cop” narrative, yet finds Soni building in its quiet, unobtrusive way towards nothing dramatic like an explosion of violence, but to a reflective moment where its two protagonists talk about Amrita Pritam’s memoir Rasidi Ticket (Revenue Stamp). Soni (Geetika Vidya Ohlyan) asks her boss Kalpana (Saloni Batra) about the book’s unusual title; the latter replies that someone had once patronizingly told Amrita-ji, why write an autobiography: “your life story could be written on the back of a revenue stamp”. This little anecdote comes just before Kalpana beseeches Soni to not resign and Soni replies “Ma’am, mere force mein rehne se kya pharak padega?” Though the point isn’t underlined, the implication is that any life – no matter how small or unremarkable it looks from a distance – can be full of meaning and resonance. Soni, like Amrita Pritam, can make a big difference in her field, whether she is investigating cases or operating telephones.

But is it possible for her to be a Dirty Harry as well, or a Singham, even on a minor scale?

I don’t want to over-stress the tonal difference between Soni and the more mainstream vigilante-cop film, because these are two disparate modes of filmmaking. One is the mythical, larger-than-life mode that uses escapism as therapy, centres around the figure of the two-fisted cop that goes back at least to the 1973 Zanjeer, and includes some of today's masala films like Simmba or Dabangg (the very look of those titles, with the double letters, suggesting a bulked-up machismo). On the other hand, there are the more grounded portraits of a policeman's life, on a canvas that might include an Ardh Satya (1983) as well as Devashish Makhija’s wonderful short film Taandav (2016), in which a cop played by Manoj Bajpayee gives vent to his feelings by performing a delirious, Nataraj-like dance.

But there's something else about Soni, something that goes beyond the Escapist Cop Film-Realistic Cop Film dichotomy. It has to do with gender roles and perceptions, with the subject of women occupying a space that is still seen as largely male, and sometimes requiring the aggressive, confrontational behaviour that is again perceived as being a male domain.

A question this film raises is: what if a woman cop loses her temper, or needs to use violence or profanity as a way of taking charge of an outrageous situation? What if a woman gives a ma-behen ki gaali to the man who is behaving fresh with her? What will the response be then, both from her antagonist (who might feel more entitled to express his anger) as well as from her team, who might be inclined to view her not just as a loose cannon but, more problematically, as a woman who is a loose cannon.

Instead of providing easy answers, Soni gives us a few vignettes from the lives of Soni and Kalpana – two women negotiating their different positions and hierarchies. Soni, being the subordinate and from a lower-class background, is the obvious underdog, and her personal frustrations often spill over into her work life: she burns with righteous anger, sometimes goes too far in dealing with transgressors or bullies, and has to be hauled up by her boss.

Instead of providing easy answers, Soni gives us a few vignettes from the lives of Soni and Kalpana – two women negotiating their different positions and hierarchies. Soni, being the subordinate and from a lower-class background, is the obvious underdog, and her personal frustrations often spill over into her work life: she burns with righteous anger, sometimes goes too far in dealing with transgressors or bullies, and has to be hauled up by her boss. However, the relatively privileged Kalpana has her constraints and problems too. Pressure to start a family, to not work the night shift. She is married to a senior cop, and one senses a tension beneath the geniality of their exchanges – a tension that may stem partly from the fact that she is clearly subservient to him in more than one sense, and has to let him pull strings for her at times. In what at first seems like a bit of indulgent playfulness in the script, but later starts to make organic sense, she is frequently addressed as “Sir” by her male subordinates – perhaps the implication is that what they respect is the "manliness" of her status and designation rather than her own worth as a person.

The film expresses all this through the extraordinary, lived-in performances of Ohlyan and Batra, the use of lengthy, handheld-camera takes that capture the daily grind of their lives, and through the sound design: from the persistent hum of disheartening news coming through the radio to the noises of the city – metro construction, men boasting about their conquests – that explode in Soni’s ears as she tries to get a grip on her life. Nervy confrontations alternate with moments of grace and empathy between the two women.

It is telling, too, that near the end the explosive statement “Dil kar raha tha goli se maar doon sab ko” is said, in a quiet tone, not by a policewoman working constantly under pressure but by a 13-year-old girl who has been subjected to a humiliating prank by her (presumably male) classmates. This violent sentiment, expressed in a soft voice, echoes through the story in one form or another. It moves beneath the film’s subdued surface, so that you’re always waiting for the explosion, for the gun to go off – and it’s all the more effective when it doesn’t happen.

Published on January 24, 2019 22:02

January 20, 2019

On Jiya Jale: Gulzar in conversation about his songs

[Did this short book review for India Today]

----------------------------

Chairing a session about Gulzar’s songs for a literature festival a few years ago, I had a minor panic attack midway through a question. It happened when I remembered that the man sitting on the next chair had written lyrics for Bimal Roy’s stark social drama Bandini in the early 1960s, and then, nearly half a century later, for Anurag Kashyap’s surreal No Smoking, Vishal Bhardwaj’s wacky Matru ki Bijli ka Mandola and Danny Boyle’s Oscar-winning Slumdog Millionaire – bridging filmmaking epochs, and movies so varied in tone, technique and sensibility that they might be completely different art forms.

And yet, Gulzar has not just retained his own distinct voice through that vast body of work: he has changed with the times, understood new contexts better than most writers of his generation, and adapted in ways that suggest he was always ahead of the curve, waiting for the zeitgeist to catch up. For instance, anyone familiar with his work will know how the unusual juxtapositions and counterintuitive imagery in his lyrics – puzzling to many critics in the 1960s – have fit right into the edgy new “multiplex” cinema. They may even have helped facilitate this new cinema, since many of today’s leading directors and screenwriters grew up with Gulzar’s writing as a guiding light.

And yet, Gulzar has not just retained his own distinct voice through that vast body of work: he has changed with the times, understood new contexts better than most writers of his generation, and adapted in ways that suggest he was always ahead of the curve, waiting for the zeitgeist to catch up. For instance, anyone familiar with his work will know how the unusual juxtapositions and counterintuitive imagery in his lyrics – puzzling to many critics in the 1960s – have fit right into the edgy new “multiplex” cinema. They may even have helped facilitate this new cinema, since many of today’s leading directors and screenwriters grew up with Gulzar’s writing as a guiding light.

It’s a daunting canvas, and for Jiya Jale, her slim book of conversations with the writer-filmmaker about his songs, Nasreen Munni Kabir took a pragmatic approach: rather than trying to be comprehensive, she focused on a few iconic songs through the decades, and allowed the conversation to take detours. This approach has worked in Kabir’s earlier books (including a previous one with Gulzar, about other aspects of his career) and it works here. In discussing how to translate the lyrics of songs such as “Chhaiyyan Chhaiyyan”, “Aane Waala Pal”, “Woh Shaam Kuch Ajeeb Thi” and “Jai Ho!” into English, layers of (intended and subtextual) meaning are uncovered. The leisurely interview format, and the comfort level between interviewer and subject, also allows for freewheeling chat on such things as the line between sensuality and vulgarity in songwriting; what love is like today, compared to in a bygone time; and the wrongfully attributed “Gulzar poems” that often get sent around as WhatsApp forwards.

And there are delightful anecdotes, such as the one about Gulzar, working for a recent film, being asked by musician Shankar Mahadevan if the song “Hum ko Mann ki Shakti Dena” (from the 1971 film Guddi) was written by him. Oh no, that is a traditional prayer we used to sing in school, said directors Shaad Ali and Rakeysh Omprakash Mehra, before Gulzar interjected and said he had indeed written the song for a prayer scene. It’s a story that nicely captures his stature in the film industry as a legend whose work has seeped into the DNA of our popular culture, and who continues to reinvent himself.

----------------------------

Chairing a session about Gulzar’s songs for a literature festival a few years ago, I had a minor panic attack midway through a question. It happened when I remembered that the man sitting on the next chair had written lyrics for Bimal Roy’s stark social drama Bandini in the early 1960s, and then, nearly half a century later, for Anurag Kashyap’s surreal No Smoking, Vishal Bhardwaj’s wacky Matru ki Bijli ka Mandola and Danny Boyle’s Oscar-winning Slumdog Millionaire – bridging filmmaking epochs, and movies so varied in tone, technique and sensibility that they might be completely different art forms.

And yet, Gulzar has not just retained his own distinct voice through that vast body of work: he has changed with the times, understood new contexts better than most writers of his generation, and adapted in ways that suggest he was always ahead of the curve, waiting for the zeitgeist to catch up. For instance, anyone familiar with his work will know how the unusual juxtapositions and counterintuitive imagery in his lyrics – puzzling to many critics in the 1960s – have fit right into the edgy new “multiplex” cinema. They may even have helped facilitate this new cinema, since many of today’s leading directors and screenwriters grew up with Gulzar’s writing as a guiding light.

And yet, Gulzar has not just retained his own distinct voice through that vast body of work: he has changed with the times, understood new contexts better than most writers of his generation, and adapted in ways that suggest he was always ahead of the curve, waiting for the zeitgeist to catch up. For instance, anyone familiar with his work will know how the unusual juxtapositions and counterintuitive imagery in his lyrics – puzzling to many critics in the 1960s – have fit right into the edgy new “multiplex” cinema. They may even have helped facilitate this new cinema, since many of today’s leading directors and screenwriters grew up with Gulzar’s writing as a guiding light.It’s a daunting canvas, and for Jiya Jale, her slim book of conversations with the writer-filmmaker about his songs, Nasreen Munni Kabir took a pragmatic approach: rather than trying to be comprehensive, she focused on a few iconic songs through the decades, and allowed the conversation to take detours. This approach has worked in Kabir’s earlier books (including a previous one with Gulzar, about other aspects of his career) and it works here. In discussing how to translate the lyrics of songs such as “Chhaiyyan Chhaiyyan”, “Aane Waala Pal”, “Woh Shaam Kuch Ajeeb Thi” and “Jai Ho!” into English, layers of (intended and subtextual) meaning are uncovered. The leisurely interview format, and the comfort level between interviewer and subject, also allows for freewheeling chat on such things as the line between sensuality and vulgarity in songwriting; what love is like today, compared to in a bygone time; and the wrongfully attributed “Gulzar poems” that often get sent around as WhatsApp forwards.

And there are delightful anecdotes, such as the one about Gulzar, working for a recent film, being asked by musician Shankar Mahadevan if the song “Hum ko Mann ki Shakti Dena” (from the 1971 film Guddi) was written by him. Oh no, that is a traditional prayer we used to sing in school, said directors Shaad Ali and Rakeysh Omprakash Mehra, before Gulzar interjected and said he had indeed written the song for a prayer scene. It’s a story that nicely captures his stature in the film industry as a legend whose work has seeped into the DNA of our popular culture, and who continues to reinvent himself.

Published on January 20, 2019 05:50

January 19, 2019

That Setsuko smile

[In my latest “moments” column for The Hindu, two classic films about lonely parents and apathetic children]

--------------------------------------

“Isn’t life disappointing?”

“Yes, it is.”

Merely set down on paper, this exchange can be interpreted in different ways. It could be a shallow, posturing, schoolboy-level show of “cynicism”. It might be a sincere but reductive expression of feeling. Or it could be hard-earned wisdom about the incurable ugliness of the world, gained from looking long and deep into the abyss.

How do you respond, though, when this exchange plays out on screen in a gentle film, made by the gentlest of filmmakers – and where the cutting line “Yes, it is” is accompanied by one of the kindest, most luminous smiles you’ll see? One that carries within it an ocean of knowingness, but also manages somehow to not be smug or patronising.

Such is the effect of this unforgettable moment near the end of Yasujiro Ozu’s 1952 classic Tokyo Story, where a young woman named Kyoko asks her sister-in-law Noriko the question – and the latter, played by the great Setsuko Hara, replies in a tone that suggests she is exchanging pleasantries with a neighbour (and with an enigmatic smile that could make the Mona Lisa envious). Over the course of the film, we have seen Noriko’s aging parents-in-law being neglected by their children, who are too busy for them. The widowed Noriko is the most sympathetic member of the younger generation. But here she is now, admitting that she too might one day “become like that, in spite of myself”.

Such is the effect of this unforgettable moment near the end of Yasujiro Ozu’s 1952 classic Tokyo Story, where a young woman named Kyoko asks her sister-in-law Noriko the question – and the latter, played by the great Setsuko Hara, replies in a tone that suggests she is exchanging pleasantries with a neighbour (and with an enigmatic smile that could make the Mona Lisa envious). Over the course of the film, we have seen Noriko’s aging parents-in-law being neglected by their children, who are too busy for them. The widowed Noriko is the most sympathetic member of the younger generation. But here she is now, admitting that she too might one day “become like that, in spite of myself”.

And as if that weren’t enough, the next line is Kyoko’s conversation-ending response: “Well. I must get going.” Followed by Noriko’s “Goodbye, then.” Again, viewed out of context, this seems to add a touch of absurdist comedy to the scene – something you may expect to find in a caustic satire by Luis Bunuel. But it is very much Ozu, clear-sighted about the unpalatable aspects of the human condition, yet also warm, accepting and willing to find solace in little acts of kindness that people direct at each other.

When I watch this scene, a few other associations come to mind. Some film buffs think of Tokyo Story as the original cinematic representation of what would become a familiar trope about old parents and apathetic (or “ungrateful”) children; in India, we have had the 1958 School Master, the 1983 Avtaar and the 2003 Baghban, among other films. But Tokyo Story itself was influenced by an older film, which is every bit as devastating: Leo McCarey’s 1937 Make Way for Tomorrow , one of the most unusual Hollywood productions of its decade.

Among the many extraordinary things in this film (which opens with the title card “There is no magic that will draw together in perfect understanding the aged and the young. There is a canyon between us”) is a final act where the old couple at the centre of the story, Lucy and Barkley, step out on their own in the big city and briefly reclaim their lives before a final painful parting. This sequence – which includes a startling, Fourth Wall-breaking moment where Lucy looks back over her shoulder, straight at us – is a heartbreaking portrayal of vulnerability as well as a defiant smile in the face of a cruel world.

briefly reclaim their lives before a final painful parting. This sequence – which includes a startling, Fourth Wall-breaking moment where Lucy looks back over her shoulder, straight at us – is a heartbreaking portrayal of vulnerability as well as a defiant smile in the face of a cruel world.

Watching these films, I also think of Philip Larkin’s poem about “man handing on misery to man (“Get out as early as you can / and don’t have any kids yourself”) and an echo of those wry lines in the writings of the anti-natalist philosopher David Benatar. Benatar advocates not having children, not because they might grow up and mistreat you, but because, in his view, life itself is a bad idea. This isn’t cynicism for the sake of it: regardless of whether you agree with him, the publicity-shy Benatar is eloquent and serious-minded in his view that life, on balance, is guaranteed to cause more suffering than happiness (also, as he points out, the worst pain will always be more long-lasting and impactful than the greatest pleasure).

A comparable view simmers below the surface of films like Tokyo Story and Make Way for Tomorrow, but it’s unlikely that the filmmakers themselves would put it in quite those terms (even as they tell stories about heartbreaks and emotional betrayals in the parent-child relationship). To watch these films is to see how, in the hands of a humanist director, moments of grace can provide a counterpoint to a bleak larger picture. Noriko looks the camera in the eye, nods and affirms that life is disappointing. But at the very same time, the shot is reminding us that there are things which make life somewhat tolerable. Like a Setsuko Hara smile in an Ozu film.

--------------------------

[Previous Hindu columns are here. An earlier post about Make Way for Tomorrow is here]

--------------------------------------

“Isn’t life disappointing?”

“Yes, it is.”

Merely set down on paper, this exchange can be interpreted in different ways. It could be a shallow, posturing, schoolboy-level show of “cynicism”. It might be a sincere but reductive expression of feeling. Or it could be hard-earned wisdom about the incurable ugliness of the world, gained from looking long and deep into the abyss.

How do you respond, though, when this exchange plays out on screen in a gentle film, made by the gentlest of filmmakers – and where the cutting line “Yes, it is” is accompanied by one of the kindest, most luminous smiles you’ll see? One that carries within it an ocean of knowingness, but also manages somehow to not be smug or patronising.

Such is the effect of this unforgettable moment near the end of Yasujiro Ozu’s 1952 classic Tokyo Story, where a young woman named Kyoko asks her sister-in-law Noriko the question – and the latter, played by the great Setsuko Hara, replies in a tone that suggests she is exchanging pleasantries with a neighbour (and with an enigmatic smile that could make the Mona Lisa envious). Over the course of the film, we have seen Noriko’s aging parents-in-law being neglected by their children, who are too busy for them. The widowed Noriko is the most sympathetic member of the younger generation. But here she is now, admitting that she too might one day “become like that, in spite of myself”.

Such is the effect of this unforgettable moment near the end of Yasujiro Ozu’s 1952 classic Tokyo Story, where a young woman named Kyoko asks her sister-in-law Noriko the question – and the latter, played by the great Setsuko Hara, replies in a tone that suggests she is exchanging pleasantries with a neighbour (and with an enigmatic smile that could make the Mona Lisa envious). Over the course of the film, we have seen Noriko’s aging parents-in-law being neglected by their children, who are too busy for them. The widowed Noriko is the most sympathetic member of the younger generation. But here she is now, admitting that she too might one day “become like that, in spite of myself”.And as if that weren’t enough, the next line is Kyoko’s conversation-ending response: “Well. I must get going.” Followed by Noriko’s “Goodbye, then.” Again, viewed out of context, this seems to add a touch of absurdist comedy to the scene – something you may expect to find in a caustic satire by Luis Bunuel. But it is very much Ozu, clear-sighted about the unpalatable aspects of the human condition, yet also warm, accepting and willing to find solace in little acts of kindness that people direct at each other.

When I watch this scene, a few other associations come to mind. Some film buffs think of Tokyo Story as the original cinematic representation of what would become a familiar trope about old parents and apathetic (or “ungrateful”) children; in India, we have had the 1958 School Master, the 1983 Avtaar and the 2003 Baghban, among other films. But Tokyo Story itself was influenced by an older film, which is every bit as devastating: Leo McCarey’s 1937 Make Way for Tomorrow , one of the most unusual Hollywood productions of its decade.

Among the many extraordinary things in this film (which opens with the title card “There is no magic that will draw together in perfect understanding the aged and the young. There is a canyon between us”) is a final act where the old couple at the centre of the story, Lucy and Barkley, step out on their own in the big city and

briefly reclaim their lives before a final painful parting. This sequence – which includes a startling, Fourth Wall-breaking moment where Lucy looks back over her shoulder, straight at us – is a heartbreaking portrayal of vulnerability as well as a defiant smile in the face of a cruel world.

briefly reclaim their lives before a final painful parting. This sequence – which includes a startling, Fourth Wall-breaking moment where Lucy looks back over her shoulder, straight at us – is a heartbreaking portrayal of vulnerability as well as a defiant smile in the face of a cruel world. Watching these films, I also think of Philip Larkin’s poem about “man handing on misery to man (“Get out as early as you can / and don’t have any kids yourself”) and an echo of those wry lines in the writings of the anti-natalist philosopher David Benatar. Benatar advocates not having children, not because they might grow up and mistreat you, but because, in his view, life itself is a bad idea. This isn’t cynicism for the sake of it: regardless of whether you agree with him, the publicity-shy Benatar is eloquent and serious-minded in his view that life, on balance, is guaranteed to cause more suffering than happiness (also, as he points out, the worst pain will always be more long-lasting and impactful than the greatest pleasure).

A comparable view simmers below the surface of films like Tokyo Story and Make Way for Tomorrow, but it’s unlikely that the filmmakers themselves would put it in quite those terms (even as they tell stories about heartbreaks and emotional betrayals in the parent-child relationship). To watch these films is to see how, in the hands of a humanist director, moments of grace can provide a counterpoint to a bleak larger picture. Noriko looks the camera in the eye, nods and affirms that life is disappointing. But at the very same time, the shot is reminding us that there are things which make life somewhat tolerable. Like a Setsuko Hara smile in an Ozu film.

--------------------------

[Previous Hindu columns are here. An earlier post about Make Way for Tomorrow is here]

Published on January 19, 2019 23:22

January 11, 2019

Gol-gappas and masala movies: on a new book about Shakespeare in popular Indian culture

[My review of one of the most stimulating books I have read in recent months -- Jonathan Gil Harris's intense and playful Masala Shakespeare: How a Firangi Writer Became Indian. A version of this piece is in the latest issue of Open magazine]

———————

Very early in Masala Shakespeare – in “Act One, Scene One: Enter Masala”, to be precise – Jonathan Gil Harris mentions the aghast reactions of his Anglophone Indian friends when he likens popular Hindi cinema to Shakespeare’s work. They decry the derivative, “cheap flash” of the former; he points out that Shakespeare’s plays, “at least as performed 400 years ago to mixed audiences of literate and illiterate, noble and poor, also routinely featured naach-gaana, often celebrated sanams (lovers) in the presence of trees, and plundered their kahaaniyan (stories) from everywhere”.

Harris isn’t making the case that mainstream Hindi films frequently achieve at the level that Shakespeare’s plays do (assuming one should even compare across mediums), but he makes an important larger point throughout this book: about the unfair denigration of “masala” art, a form where many tones and moods coexist, where the classical Aristotelian unities are not heeded, and “too-muchness” can be a virtue. “In the masala movie, there is no space for purity. Elements that are supposedly separate and even incompatible bed down under the same roof: tragedy consorts with comedy, poetic language with coarse slang, prim morality with unbounded desire, congested Indian gaalis with rolling Swiss mountains, conversational dialogues with song and dance, desi cowboys with desi Indians, Hindi with Urdu, Hindustani with English, Punjabi with Bhojpuri.”

Harris isn’t making the case that mainstream Hindi films frequently achieve at the level that Shakespeare’s plays do (assuming one should even compare across mediums), but he makes an important larger point throughout this book: about the unfair denigration of “masala” art, a form where many tones and moods coexist, where the classical Aristotelian unities are not heeded, and “too-muchness” can be a virtue. “In the masala movie, there is no space for purity. Elements that are supposedly separate and even incompatible bed down under the same roof: tragedy consorts with comedy, poetic language with coarse slang, prim morality with unbounded desire, congested Indian gaalis with rolling Swiss mountains, conversational dialogues with song and dance, desi cowboys with desi Indians, Hindi with Urdu, Hindustani with English, Punjabi with Bhojpuri.”

These are just two among many heart-gladdening passages in this much-needed book. Playful and erudite at the same time, Masala Shakespeare took me back to my first reading – as a teen obsessed with old Hollywood – of a favourite book, Robin Wood’s Hitchcock’s Films Revisited. Here was an academic with a literary background comparing a genre film like Psycho with Shakespeare’s Macbeth, and pointing out that an oft-derided musical scene in Howard Hawks’s western Rio Bravo was easier to justify, in terms of thematic unity, than the role of Autolycus in The Winter’s Tale (“a concession to popular taste that, one feels, delighted Shakespeare’s heart very much”). Harris mounts similar – if not exactly analogous – arguments about the relationship between Shakespeare and many aspects of Indian popular culture, including cinema.

The Shakespeare-Bollywood comparison is not a new one, but recognizing the connection requires both a close engagement with the Bard’s plays in their original form (as opposed to the Lamb abridgements, which lead a reader to focus on plot rather than on rhythms of language and idiosyncratic structures) and being stimulated by and open-minded toward pop-culture, including “massy” movies. Understandably, not many people combine these qualities. (Naseeruddin Shah in his memoir And Then One Day… uses the comparison to run down popular Hindi cinema and to run down certain aspects of Shakespeare too!) But Harris does this with vigour and affection. It helps that he is himself a product of a very mixed heritage. Born in New Zealand, living most of his early life in England and the US, he first visited India in 2001, became fascinated by the country’s diversity, settled down here, and grew to understand and love such things as the gol-gappa and Hindi cinema: two creations made up of unsettlingly varied ingredients, which one might gradually acquire a taste for.

Masala, mixture, multiplicity, more-than-oneness ... these are words that recur through this book. They link the tonal variedness in Shakespeare’s work with the pluralism of Indian cultural forms, and with India itself – a plurality that is in danger now owing to the hardline Hindutva movement and its harking back to the ideal of a singular, “pure” Hindu rashtra. Inevitably, this is also where the book acquires its more political stance: Harris touches on current events such as the proliferation of “anti-Romeo squads” (which ironically are more about restraining India’s “Juliets”) and the lynching of minorities, as well as displays of hyper-masculinity and nationalistic jingoism that counter India’s syncretic history.

Done differently, Masala Shakespeare might have invited the allegation that it stretches a point too much. That this doesn’t happen is a tribute to Harris’s literary criticism and his attention to detail. A point arrived when I stopped thinking about the central argument and instead began delighting in the minutiae – the same way one might relish a good mainstream film like Amar Akbar Anthony not for the “message” about communal harmony (which can be quickly absorbed), but for the quality of the ingredients.

Included here are analyses of well-known, clearly Shakespearean films (the Vishal Bhardwaj trilogy, Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s glorious Goliyon ki Raas-Leela Raam Leela), films that on the surface have little to do with the Bard (Dil Chahta Hai, Lagaan), and under-seen works like Isi Life Mein, a Taming of the Shrew adaptation, and 10 ml Love, a Midsummer Night’s Dream set in contemporary Mumbai. Harris looks closely at nautanki versions such as the Twelfth Night reimagining Piya Behrupiya, a multi-lingual (“more accurately, trans-lingual”) play that includes – to the delight of viewers like me who fondly remember the lowbrow wordplay of Kader Khan and company in 1980s Hindi films – a scene where the Toby Belch character says “I am Toby, and you are my Gobi”. He discusses the cult of Hamlet in the theatrical traditions of marginalized states like Mizoram, and even encourages his Ashoka University students to stage a Pericles adaptation (the magnificently titled "Hera-Phericles" is the innovative result). He also examines the Shakespeare-India connect in literature ranging from Vikram Seth’s A Suitable Boy and Salman Rushdie’s The Moor’s Last Sigh to more recent novels such as Preti Taneja’s We That Are Young, Saikat Majumdar’s Firebird, and Anjum Hasan’s Neti Neti.

delight of viewers like me who fondly remember the lowbrow wordplay of Kader Khan and company in 1980s Hindi films – a scene where the Toby Belch character says “I am Toby, and you are my Gobi”. He discusses the cult of Hamlet in the theatrical traditions of marginalized states like Mizoram, and even encourages his Ashoka University students to stage a Pericles adaptation (the magnificently titled "Hera-Phericles" is the innovative result). He also examines the Shakespeare-India connect in literature ranging from Vikram Seth’s A Suitable Boy and Salman Rushdie’s The Moor’s Last Sigh to more recent novels such as Preti Taneja’s We That Are Young, Saikat Majumdar’s Firebird, and Anjum Hasan’s Neti Neti.

Even if you don't agree with all his observations, there are many fine insights. How interesting, for instance, to consider that the Karan Johar-produced 2012 film Agneepath is, not just at the level of its plot, a Hamlet-like story about sons trying to remedy the wrongs done to their fathers (the original 1990 Agneepath was produced by Johar’s father Yash Johar, who was devastated by its failure). Or that the falling note in the Omkara song “O Saathi Re” – suggestive of looming tragedy, contrapuntal to the blissful romantic scene it accompanies in the film – may be likened to Shakespeare’s repeated use, in Othello, of an iambic meter where a line trails away rather than ending with a “masculine” stressed syllable. Or how Rituparno Ghosh’s The Last Lear, even as it “genuflects at the altar of a singular Shakespeare-devta ... Thomas Macaulay's Shakespeare, the repository of high art”, does this by casting mainstream superstar Amitabh Bachchan in the lead and commenting on Bachchan's screen persona in a “lower” form, popular cinema.

For me, reading this book was also to be alerted to little details about Shakespeare plays that I had either been unaware of or never grasped the implications of. For instance, despite a passing familiarity with The Taming of the Shrew (mostly through films, including the now-very-quaint 1929 Douglas Fairbanks-Mary Pickford version), I never realized that the main story of that play is in fact a performed narrative, framed by another tale about a hallucinating nobleman. (As Harris points out, the wholesale removal of the framing story in most theatrical performances has a big effect on how one reads or interprets the play, including the seemingly regressive climactic speech made by the “tamed” Katherina.) Elsewhere, discussing the opening of Romeo and Juliet, where two street-fighters engage in a delirious verbal joust, he reasserts that Shakespeare’s vitality resides in how his plays sound to the ear (as opposed to look on the page, merely read, as so many generations of students in India and elsewhere have dutifully done) but also notes how a seemingly fluffy bit of stage business can pre-echo the main themes of a profound tragedy. In so doing, he also extols the virtues of that most denigrated of comedic devices, the pun, observing that Gregory and Sampson’s wordplay prepares us for Romeo and Juliet’s first meeting, “when Romeo the Montague breaks into the Capulet masque wearing a mask. Romeo is a pun here: two identities in one”.