Jai Arjun Singh's Blog, page 33

April 5, 2019

One way of reading anthologies (and a memory of two Guy de Maupassant stories)

[my “Bookshelves” column this month is about my teenage love of short-story collections, including a 1000-page anthology of Maupassant’s writings]

-------------------------------------

Opening a new anthology, The Gollancz Book of South Asian Science Fiction, I found myself reflexively following a ritual developed in childhood. I looked at the page numbers listed on the Contents page, homed in on the shortest stories, and picked one. After finishing the story, I put a little dot next to the title, as a reminder that I had read it (this is especially useful if the anthology is a fat one), before moving on to the next, slightly longer story.

I have dozens of thick books filled with those little dots. (A time-lapse video depiction of my encounters with Contents pages over the decades might begin with a close-up of a child’s hand awkwardly marking a story title with a pencil, then dissolve into a shot of an adult hand, this time holding a pen, doing the same thing on the page of a more grown-up-looking book.) Such anthologies – short-story collections, organized by genre or author – were a big part of my teenage reading life. They helped me discover some favourite writers, including Roald Dahl, Damon Runyon, Saki… and Guy de Maupassant, a collection of whose short fiction became – improbably – a treasured book.

I have dozens of thick books filled with those little dots. (A time-lapse video depiction of my encounters with Contents pages over the decades might begin with a close-up of a child’s hand awkwardly marking a story title with a pencil, then dissolve into a shot of an adult hand, this time holding a pen, doing the same thing on the page of a more grown-up-looking book.) Such anthologies – short-story collections, organized by genre or author – were a big part of my teenage reading life. They helped me discover some favourite writers, including Roald Dahl, Damon Runyon, Saki… and Guy de Maupassant, a collection of whose short fiction became – improbably – a treasured book.

I don’t remember how I stumbled on Maupassant, but I remember the little thrill I felt when an acquaintance who knew a bit of French saw my book and, sotto voce, let me into a secret that I could impress friends and family with: the “Guy” was pronounced “Gee” with a soft G. I still have the simple-looking anthology, which was priced at just Rs 125 (in 1991). The printing and binding standards aren’t great, but it has held together. No translator’s name is mentioned anywhere in this book. And the cover, while it may have been apposite to some of Maupassant’s stories, seems like it was there purely to tantalize the casual browser: a young woman holding up a cloth in front of her, her bare back turned towards the reader. Having become a cinephile around the same time (and watching films I was too young to watch), I thought this woman looked a little like the beautiful French actress Catherine Deneuve in one of the steamier scenes from Belle de Jour.

Much as I enjoyed this book, it was a daunting beast – more than a thousand pages in very small font – and looking at the little dots on the Contents pages now, I find that I have read only around half of the 200-plus stories in it. So I won’t make any grand statements about Maupassant’s body of work. What I do remember is that for me, much of his writing was “adult” in ways that had little to do with sexually explicit content. It opened a window of insight into the mysteries of adult behaviour, and examined ideas and conflicts I had no firsthand experience of at the time.

Two stories in particular stuck with me, creating associations that I couldn’t have articulated as an adolescent, but which I understand better now. The first, a reflection on how the human mind moves constantly between rationality and irrational dread, was “Beside a Dead Man”, in which two men are tasked with spending the night alongside the dead body of the philosopher Schopenhauer. Unpleasant as this vigil is, it is made more so by the fact that the deceased had “a frightful smile” even in life; as the night wears on, the men are terrified by the sense of an “immaterial essence” – a soul, or something scarier? – persisting after death. Then they catch a glimpse of something white flying out of the corpse and through the air, and notice that his grin has become even more macabre than before. The story ends in an offhand manner, with a non-supernatural explanation, but that almost doesn’t matter: so tangible is the sense of fear and claustrophobia that has been created along the way.

Two stories in particular stuck with me, creating associations that I couldn’t have articulated as an adolescent, but which I understand better now. The first, a reflection on how the human mind moves constantly between rationality and irrational dread, was “Beside a Dead Man”, in which two men are tasked with spending the night alongside the dead body of the philosopher Schopenhauer. Unpleasant as this vigil is, it is made more so by the fact that the deceased had “a frightful smile” even in life; as the night wears on, the men are terrified by the sense of an “immaterial essence” – a soul, or something scarier? – persisting after death. Then they catch a glimpse of something white flying out of the corpse and through the air, and notice that his grin has become even more macabre than before. The story ends in an offhand manner, with a non-supernatural explanation, but that almost doesn’t matter: so tangible is the sense of fear and claustrophobia that has been created along the way.

The other story is also, in a way, about the process of decomposition or decay – but in life, rather than after death. In “A Family”, the narrator meets an old friend named Simon – a once-vigorous, intellectually robust young man – and finds him transformed after 15 years of marriage into a stout, parochial householder: someone who now seems to regard the fathering of children as his life’s major achievement, having concluded which he can sit back in satisfaction. “I felt profound pity, mingled with a feeling of vague contempt, for this vainglorious and simple reproducer of his species who spent his nights in his country house in uxurious pleasures.”

The story’s depressing climax is a dinner-table scene where Simon, his wife and children, much to the narrator’s horror, derive pleasure from the suffering of a 90-year-old grandfather who is denied the food he wants to eat because “it might harm him”. And also because watching the old man beg and cry is one of their few daily sources of amusement.

As a teenager, long before I knew about the more contemptuous associations around the word “bourgeoisie”, I intuitively understood how this narrator felt. I had had a similarly disenchanting encounter with a much older cousin whom I once hero-worshipped, and discussed books and films with – but who had turned into a corporate type, incapable of talking about anything other than his business-related anxieties.

And yet, rereading “A Family” recently, I found a subtle shift in my response. To a degree, I could still relate with the narrator’s dismay, and the family’s treatment of the old grandfather had lost none of its nastiness. But I also found much to cringe at in the smug superiority with which the narrator denounces the domestic life, and his description of Simon’s wife as “a commonplace mother”, “a brood mare” and a “machine of flesh which procreates without mental care”. These judgements now felt just as narrow, petty and provincial. Whether or not Maupassant consciously intended such conflicting interpretations, his stories, like so much other good literature, are a reminder of how we change with time and experience – and how what we read changes with us.

[Earlier Bookshelves column here]

-------------------------------------

Opening a new anthology, The Gollancz Book of South Asian Science Fiction, I found myself reflexively following a ritual developed in childhood. I looked at the page numbers listed on the Contents page, homed in on the shortest stories, and picked one. After finishing the story, I put a little dot next to the title, as a reminder that I had read it (this is especially useful if the anthology is a fat one), before moving on to the next, slightly longer story.

I have dozens of thick books filled with those little dots. (A time-lapse video depiction of my encounters with Contents pages over the decades might begin with a close-up of a child’s hand awkwardly marking a story title with a pencil, then dissolve into a shot of an adult hand, this time holding a pen, doing the same thing on the page of a more grown-up-looking book.) Such anthologies – short-story collections, organized by genre or author – were a big part of my teenage reading life. They helped me discover some favourite writers, including Roald Dahl, Damon Runyon, Saki… and Guy de Maupassant, a collection of whose short fiction became – improbably – a treasured book.

I have dozens of thick books filled with those little dots. (A time-lapse video depiction of my encounters with Contents pages over the decades might begin with a close-up of a child’s hand awkwardly marking a story title with a pencil, then dissolve into a shot of an adult hand, this time holding a pen, doing the same thing on the page of a more grown-up-looking book.) Such anthologies – short-story collections, organized by genre or author – were a big part of my teenage reading life. They helped me discover some favourite writers, including Roald Dahl, Damon Runyon, Saki… and Guy de Maupassant, a collection of whose short fiction became – improbably – a treasured book. I don’t remember how I stumbled on Maupassant, but I remember the little thrill I felt when an acquaintance who knew a bit of French saw my book and, sotto voce, let me into a secret that I could impress friends and family with: the “Guy” was pronounced “Gee” with a soft G. I still have the simple-looking anthology, which was priced at just Rs 125 (in 1991). The printing and binding standards aren’t great, but it has held together. No translator’s name is mentioned anywhere in this book. And the cover, while it may have been apposite to some of Maupassant’s stories, seems like it was there purely to tantalize the casual browser: a young woman holding up a cloth in front of her, her bare back turned towards the reader. Having become a cinephile around the same time (and watching films I was too young to watch), I thought this woman looked a little like the beautiful French actress Catherine Deneuve in one of the steamier scenes from Belle de Jour.

Much as I enjoyed this book, it was a daunting beast – more than a thousand pages in very small font – and looking at the little dots on the Contents pages now, I find that I have read only around half of the 200-plus stories in it. So I won’t make any grand statements about Maupassant’s body of work. What I do remember is that for me, much of his writing was “adult” in ways that had little to do with sexually explicit content. It opened a window of insight into the mysteries of adult behaviour, and examined ideas and conflicts I had no firsthand experience of at the time.

Two stories in particular stuck with me, creating associations that I couldn’t have articulated as an adolescent, but which I understand better now. The first, a reflection on how the human mind moves constantly between rationality and irrational dread, was “Beside a Dead Man”, in which two men are tasked with spending the night alongside the dead body of the philosopher Schopenhauer. Unpleasant as this vigil is, it is made more so by the fact that the deceased had “a frightful smile” even in life; as the night wears on, the men are terrified by the sense of an “immaterial essence” – a soul, or something scarier? – persisting after death. Then they catch a glimpse of something white flying out of the corpse and through the air, and notice that his grin has become even more macabre than before. The story ends in an offhand manner, with a non-supernatural explanation, but that almost doesn’t matter: so tangible is the sense of fear and claustrophobia that has been created along the way.

Two stories in particular stuck with me, creating associations that I couldn’t have articulated as an adolescent, but which I understand better now. The first, a reflection on how the human mind moves constantly between rationality and irrational dread, was “Beside a Dead Man”, in which two men are tasked with spending the night alongside the dead body of the philosopher Schopenhauer. Unpleasant as this vigil is, it is made more so by the fact that the deceased had “a frightful smile” even in life; as the night wears on, the men are terrified by the sense of an “immaterial essence” – a soul, or something scarier? – persisting after death. Then they catch a glimpse of something white flying out of the corpse and through the air, and notice that his grin has become even more macabre than before. The story ends in an offhand manner, with a non-supernatural explanation, but that almost doesn’t matter: so tangible is the sense of fear and claustrophobia that has been created along the way.The other story is also, in a way, about the process of decomposition or decay – but in life, rather than after death. In “A Family”, the narrator meets an old friend named Simon – a once-vigorous, intellectually robust young man – and finds him transformed after 15 years of marriage into a stout, parochial householder: someone who now seems to regard the fathering of children as his life’s major achievement, having concluded which he can sit back in satisfaction. “I felt profound pity, mingled with a feeling of vague contempt, for this vainglorious and simple reproducer of his species who spent his nights in his country house in uxurious pleasures.”

The story’s depressing climax is a dinner-table scene where Simon, his wife and children, much to the narrator’s horror, derive pleasure from the suffering of a 90-year-old grandfather who is denied the food he wants to eat because “it might harm him”. And also because watching the old man beg and cry is one of their few daily sources of amusement.

As a teenager, long before I knew about the more contemptuous associations around the word “bourgeoisie”, I intuitively understood how this narrator felt. I had had a similarly disenchanting encounter with a much older cousin whom I once hero-worshipped, and discussed books and films with – but who had turned into a corporate type, incapable of talking about anything other than his business-related anxieties.

And yet, rereading “A Family” recently, I found a subtle shift in my response. To a degree, I could still relate with the narrator’s dismay, and the family’s treatment of the old grandfather had lost none of its nastiness. But I also found much to cringe at in the smug superiority with which the narrator denounces the domestic life, and his description of Simon’s wife as “a commonplace mother”, “a brood mare” and a “machine of flesh which procreates without mental care”. These judgements now felt just as narrow, petty and provincial. Whether or not Maupassant consciously intended such conflicting interpretations, his stories, like so much other good literature, are a reminder of how we change with time and experience – and how what we read changes with us.

[Earlier Bookshelves column here]

Published on April 05, 2019 18:57

March 30, 2019

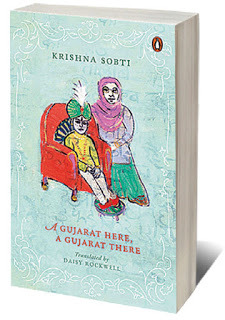

Many partitions: on Krishna Sobti’s last book गुजरात पाकिस्तान से गुजरात हिंदुस्तान

[Did this book review for Open magazine]

---------------

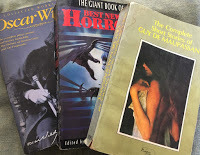

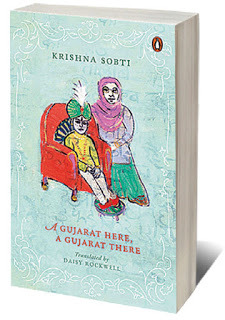

Around 80 pages into A Gujarat Here, A Gujarat There – the English translation of Krishna Sobti’s novelized memoir about a young woman seeking a preschool job in the princely state Sirohi shortly after Partition – comes a chapter that marks a shift from the narrative we have so far experienced. Up to this point, the book has been in a third-person voice, albeit a subjective or limited one that keeps us tied to Krishna’s actions and thoughts. Now this chapter, printed in another font – more cursive and childlike – has Krishna writing in the first person, recalling a birthday picnic she had successfully organized for her friends during her college days in Lahore.

Food and tea were ordered – from a restaurant that had its own van, which could deliver anywhere in the city – and the Principal Sahiba was persuaded to allow a riverside party. A minor boat accident during the picnic led to two boys joining the group. Folk songs, ghazals and poems were recited, everyone had a good time. But in Krishna’s telling, the party also lost some of its sheen because it grew dark very suddenly – and because she didn’t know if she and her friends would ever return to that idyllic spot for another such celebration.

Food and tea were ordered – from a restaurant that had its own van, which could deliver anywhere in the city – and the Principal Sahiba was persuaded to allow a riverside party. A minor boat accident during the picnic led to two boys joining the group. Folk songs, ghazals and poems were recited, everyone had a good time. But in Krishna’s telling, the party also lost some of its sheen because it grew dark very suddenly – and because she didn’t know if she and her friends would ever return to that idyllic spot for another such celebration.

Is this a premonition of partings to come, one wonders, or is she writing with the benefit of hindsight, adding a dab of melancholia to an episode that was unrestrictedly happy when it took place?

The sense of a childhood lost – or ending before one realizes it, in the storm of Partition – is vivid, but equally notable is how it sneaks up on us. The change in font and perspective has prepared us for something different, but as the memory-dream unfolds we yield to its languid flow. And then, in the last lines, without anything overtly dramatic taking place, the chattering of young people gives way to an ominous stillness. There is something very cinematic about the episode, and very haunting in the way it disrupts the main story.

That story is a seemingly straightforward one. A refugee from Delhi, young Krishna – headstrong and wavering in turn – arrives in Sirohi where she must deal with self-doubts as well as some resistance from the educational director, Zutshi Sahib, who would have preferred another candidate for the job. She meets the more welcoming Divan Sahib, as well as members of the royal family; she travels on work to Ahmedabad and Bombay, in the process also spending time with some of her relatives and slipping into other distant memories; on returning to Sirohi, since the preschool has not yet opened, she is employed as governess to the four-year-old Maharajah Tej Singh, and witnesses the political intrigues and inter-clan rivalries bearing down on a way of life that is about to fade.

****

Reading this memoir, with limited knowledge of Sobti’s earlier work, two things leaped out at me. First, the celebrated author – who passed away this year, aged 93 – was well into her eighties when she wrote this book (the original was published in 2016). Second, the playful experimentalism of the writing. Though I was personally very taken by the picnic interlude mentioned above, that isn’t the first instance of the book deviating from linear storytelling – there are other asides and disruptions. Early on, for instance, there is a long stream-of-consciousness passage, made up of disjointed thoughts about the 1947 massacres: about the many Abduls and Rams who turned on each other; how the gulistan ki bulbulein (the rose garden’s nightingales, a reference to a line from the Indian national anthem) stopped making sweet music in unison and took up knives and cleavers instead.

Much later, even as the third-person narrative continues, a delicate shift occurs: where Krishna was earlier referred to only as “she” or “her”, she is now variously called “Bai” or “the Governess” or “Ma’am”, with the reference sometimes changing from one paragraph to another depending on context and terms of engagement. It is as if the book’s canvas is expanding to accommodate the perspectives of other people – the maids appointed to serve her, the child maharajah, the other royals – and her identity is being broadened from being just “that refugee girl” to something fuller, something that commands respect. Or perhaps this is only happening in her own mind?

Then there are the many short, staccato sentences – in that picnic account, for example. “Colourful dupattas and fresh river breezes. […] The imposing height of the principal sahiba. A unique glow to her face. Her hair pulled back in a small bun. A white sari with a white border. Kanchan Lata Sabarwal. A unique personality. […] The banks of the Ravi. Boating. Girls splashing into water, then a rescue. Tea from the Standard.”

It’s possible to wonder if some of these characteristics of Sobti’s prose might have a practical source: an aging writer putting things down as quickly as possible, perhaps even conserving energy by not writing full sentences. As translator Daisy Rockwell suggests in her Introduction, this book has the feel of an old person drawing on ancient memories, including seemingly trivial ones, and setting them down simply because she remembered them and wanted to preserve them. However, Rockwell also points to the more general difficulty of translating Sobti, who doesn’t set out to make things easy for a reader by describing things at length, but often uses language in a condensed, fragmentary way to convey impressions.

preserve them. However, Rockwell also points to the more general difficulty of translating Sobti, who doesn’t set out to make things easy for a reader by describing things at length, but often uses language in a condensed, fragmentary way to convey impressions.

These formal qualities – the restlessness, the memories bleeding into each other, the shifting of viewpoints even within a broadly standardized narrative voice, the hint of fractured personalities – are well suited to a book that has the shadow of Partition over it. The title refers to two Gujarats – the Indian state that Sirohi is on the verge of being assimilated into, and the district that is now in Pakistan (usually spelt “Gujrat” in English, but spelled the same way as the Indian Gujarat for the purposes of this book). But there are other partitions here, as there are elsewhere in Sobti’s writings. Having used the male pseudonym Hashmat for some of her work (as Rockwell points out, she even took a little dig at “Krishna Sobti” while writing in this voice!), she certainly knew about the many dualities present in people. The Krishna of this story is internally divided herself, vacillating in her early days in Sirohi (she contemplates going back to the station a few minutes after arriving) – and interestingly, when she does make up her mind, it comes from defiance, after she happens to learn that Zutshi Sahib doesn’t want her in the position.

Other divides that run through this book include the one between past and present (or looking back and looking forward), between childhood innocence and adult pragmatism, between Rajputs, the merchant class and Brahmins, between the types of clothes that people wear in different states and kingdoms, between the old world where a little child may be taught how to comport himself as a ruler, and the rapidly arriving new one where there is only a proud young democracy with no time for the fancies and protocols of kings (at least not of the old variety).

And there are the partitions that separate ghosts from the living, as Krishna discovers when she is haunted by the spirits of friends and acquaintances who were murdered during the riots. “Krishna Krishna,” one of them teased her when they were children, “As thirsty as a well / How much water will you pull / How much thirst will you quench / As much nectar as you drink / That’s how long you’ll live.” It’s a reminder of the pressures that the octogenarian Krishna Sobti must have carried as a living well of memories, writing furiously, using mind and pen to give voice to those whom she had survived by so many decades.

---------------

Around 80 pages into A Gujarat Here, A Gujarat There – the English translation of Krishna Sobti’s novelized memoir about a young woman seeking a preschool job in the princely state Sirohi shortly after Partition – comes a chapter that marks a shift from the narrative we have so far experienced. Up to this point, the book has been in a third-person voice, albeit a subjective or limited one that keeps us tied to Krishna’s actions and thoughts. Now this chapter, printed in another font – more cursive and childlike – has Krishna writing in the first person, recalling a birthday picnic she had successfully organized for her friends during her college days in Lahore.

Food and tea were ordered – from a restaurant that had its own van, which could deliver anywhere in the city – and the Principal Sahiba was persuaded to allow a riverside party. A minor boat accident during the picnic led to two boys joining the group. Folk songs, ghazals and poems were recited, everyone had a good time. But in Krishna’s telling, the party also lost some of its sheen because it grew dark very suddenly – and because she didn’t know if she and her friends would ever return to that idyllic spot for another such celebration.

Food and tea were ordered – from a restaurant that had its own van, which could deliver anywhere in the city – and the Principal Sahiba was persuaded to allow a riverside party. A minor boat accident during the picnic led to two boys joining the group. Folk songs, ghazals and poems were recited, everyone had a good time. But in Krishna’s telling, the party also lost some of its sheen because it grew dark very suddenly – and because she didn’t know if she and her friends would ever return to that idyllic spot for another such celebration. Is this a premonition of partings to come, one wonders, or is she writing with the benefit of hindsight, adding a dab of melancholia to an episode that was unrestrictedly happy when it took place?

The sense of a childhood lost – or ending before one realizes it, in the storm of Partition – is vivid, but equally notable is how it sneaks up on us. The change in font and perspective has prepared us for something different, but as the memory-dream unfolds we yield to its languid flow. And then, in the last lines, without anything overtly dramatic taking place, the chattering of young people gives way to an ominous stillness. There is something very cinematic about the episode, and very haunting in the way it disrupts the main story.

That story is a seemingly straightforward one. A refugee from Delhi, young Krishna – headstrong and wavering in turn – arrives in Sirohi where she must deal with self-doubts as well as some resistance from the educational director, Zutshi Sahib, who would have preferred another candidate for the job. She meets the more welcoming Divan Sahib, as well as members of the royal family; she travels on work to Ahmedabad and Bombay, in the process also spending time with some of her relatives and slipping into other distant memories; on returning to Sirohi, since the preschool has not yet opened, she is employed as governess to the four-year-old Maharajah Tej Singh, and witnesses the political intrigues and inter-clan rivalries bearing down on a way of life that is about to fade.

****

Reading this memoir, with limited knowledge of Sobti’s earlier work, two things leaped out at me. First, the celebrated author – who passed away this year, aged 93 – was well into her eighties when she wrote this book (the original was published in 2016). Second, the playful experimentalism of the writing. Though I was personally very taken by the picnic interlude mentioned above, that isn’t the first instance of the book deviating from linear storytelling – there are other asides and disruptions. Early on, for instance, there is a long stream-of-consciousness passage, made up of disjointed thoughts about the 1947 massacres: about the many Abduls and Rams who turned on each other; how the gulistan ki bulbulein (the rose garden’s nightingales, a reference to a line from the Indian national anthem) stopped making sweet music in unison and took up knives and cleavers instead.

Much later, even as the third-person narrative continues, a delicate shift occurs: where Krishna was earlier referred to only as “she” or “her”, she is now variously called “Bai” or “the Governess” or “Ma’am”, with the reference sometimes changing from one paragraph to another depending on context and terms of engagement. It is as if the book’s canvas is expanding to accommodate the perspectives of other people – the maids appointed to serve her, the child maharajah, the other royals – and her identity is being broadened from being just “that refugee girl” to something fuller, something that commands respect. Or perhaps this is only happening in her own mind?

Then there are the many short, staccato sentences – in that picnic account, for example. “Colourful dupattas and fresh river breezes. […] The imposing height of the principal sahiba. A unique glow to her face. Her hair pulled back in a small bun. A white sari with a white border. Kanchan Lata Sabarwal. A unique personality. […] The banks of the Ravi. Boating. Girls splashing into water, then a rescue. Tea from the Standard.”

It’s possible to wonder if some of these characteristics of Sobti’s prose might have a practical source: an aging writer putting things down as quickly as possible, perhaps even conserving energy by not writing full sentences. As translator Daisy Rockwell suggests in her Introduction, this book has the feel of an old person drawing on ancient memories, including seemingly trivial ones, and setting them down simply because she remembered them and wanted to

preserve them. However, Rockwell also points to the more general difficulty of translating Sobti, who doesn’t set out to make things easy for a reader by describing things at length, but often uses language in a condensed, fragmentary way to convey impressions.

preserve them. However, Rockwell also points to the more general difficulty of translating Sobti, who doesn’t set out to make things easy for a reader by describing things at length, but often uses language in a condensed, fragmentary way to convey impressions. These formal qualities – the restlessness, the memories bleeding into each other, the shifting of viewpoints even within a broadly standardized narrative voice, the hint of fractured personalities – are well suited to a book that has the shadow of Partition over it. The title refers to two Gujarats – the Indian state that Sirohi is on the verge of being assimilated into, and the district that is now in Pakistan (usually spelt “Gujrat” in English, but spelled the same way as the Indian Gujarat for the purposes of this book). But there are other partitions here, as there are elsewhere in Sobti’s writings. Having used the male pseudonym Hashmat for some of her work (as Rockwell points out, she even took a little dig at “Krishna Sobti” while writing in this voice!), she certainly knew about the many dualities present in people. The Krishna of this story is internally divided herself, vacillating in her early days in Sirohi (she contemplates going back to the station a few minutes after arriving) – and interestingly, when she does make up her mind, it comes from defiance, after she happens to learn that Zutshi Sahib doesn’t want her in the position.

Other divides that run through this book include the one between past and present (or looking back and looking forward), between childhood innocence and adult pragmatism, between Rajputs, the merchant class and Brahmins, between the types of clothes that people wear in different states and kingdoms, between the old world where a little child may be taught how to comport himself as a ruler, and the rapidly arriving new one where there is only a proud young democracy with no time for the fancies and protocols of kings (at least not of the old variety).

And there are the partitions that separate ghosts from the living, as Krishna discovers when she is haunted by the spirits of friends and acquaintances who were murdered during the riots. “Krishna Krishna,” one of them teased her when they were children, “As thirsty as a well / How much water will you pull / How much thirst will you quench / As much nectar as you drink / That’s how long you’ll live.” It’s a reminder of the pressures that the octogenarian Krishna Sobti must have carried as a living well of memories, writing furiously, using mind and pen to give voice to those whom she had survived by so many decades.

Published on March 30, 2019 01:12

March 27, 2019

The Flashback series: why you should watch Guru Dutt’s Mr and Mrs 55

[my latest Film Companion piece]

--------------------

Title: Mr and Mrs 55

Director: Guru Dutt

Year: 1955

Cast: Madhubala, Guru Dutt, Lalita Pawar, Johnny Walker

Why you should watch it:

Why you should watch it:

Because it’s Guru Dutt Lite (but points the way forward to his more personal work)

A confession: though I admire the major Guru Dutt films – the grandly dramatic ones, Pyaasa and Kaagaz ke Phool – and especially the individual elements that make them great (camerawork, music, lyrics, Waheeda Rehman), I am sidestepping them in this column. Part of this has to do with my reservations about Guru Dutt the actor when he is playing an overtly serious, sympathy-seeking part.

At the same time, Dutt’s earliest ventures into directing – such as Baazi and Jaal – don’t have enough of his distinct authorial personality. A fine middle ground can be discovered in Mr and Mrs 55, which has a charming performance by Dutt the actor and solid contributions by some of his most important collaborators – notably writer Abrar Alvi and cinematographer VK Murthy – while being both a romantic comedy and a (mildly pedantic) social statement.

At the same time, Dutt’s earliest ventures into directing – such as Baazi and Jaal – don’t have enough of his distinct authorial personality. A fine middle ground can be discovered in Mr and Mrs 55, which has a charming performance by Dutt the actor and solid contributions by some of his most important collaborators – notably writer Abrar Alvi and cinematographer VK Murthy – while being both a romantic comedy and a (mildly pedantic) social statement.

And it even has a key Guru Dutt motif, which would be seen in his two iconic tragedies later in the decade – the theme of the artist in the gutter, impoverished and trampled on – but treated with lightness in this film. Dutt plays an unemployed cartoonist named Preetam, dependent for money and accommodation on his reporter friend Johnny (the wonderful Johnny Walker, who, you may recall, was also the rescuer-in-chief in Pyaasa). Then he meets the heiress Anita (Madhubala) as well as her aunt Sita Devi – a man-hating firebrand feminist, played by the great Lalita Pawar – who wants Anita to get married so she can get her inheritance (followed quickly by a divorce). Preetam is hired to be the temporary husband, but meanwhile he and Anita are falling in and out of love with each other.

For the sharp writing, the general air of zaniness… and RK Laxman

The film’s opening credits combine an image that could easily have come out of a Hollywood classic like The Philadelphia Story (a newspaper headline reads “Husband of Heiress Admits Infidelity”) with the work of a celebrated Indian cartoonist: RK Laxman, who did a very funny drawing specifically for the film (it shows the authoritarian Sita Devi riding a chariot pulled by Preetam and Anita).

The wacky tone persists for much of the film. Alvi’s dialogues sparkle, especially in the more lighthearted first half where we see professionals like doctors and lawyers – such solemn characters in other films of the time – behaving somewhat like Groucho Marx. Take the hilarious scene where a sad-looking physician examines the unwell Preetam and then has a surreal conversation with Johnny, shaking his head at the plight of this BA Pass cartoonist who only has a single pair of trousers. Or the one where an impish lawyer annoys Sita Devi while she tries to discuss the terms of her brother’s will.

The wacky tone persists for much of the film. Alvi’s dialogues sparkle, especially in the more lighthearted first half where we see professionals like doctors and lawyers – such solemn characters in other films of the time – behaving somewhat like Groucho Marx. Take the hilarious scene where a sad-looking physician examines the unwell Preetam and then has a surreal conversation with Johnny, shaking his head at the plight of this BA Pass cartoonist who only has a single pair of trousers. Or the one where an impish lawyer annoys Sita Devi while she tries to discuss the terms of her brother’s will.

Among the many other little moments, I love the scene where a non-nonsense nanny remarks “Hamaaray zamaanay mein prem karte thay khaana khaakay, bhookhe pet nahin” when a lovelorn Anita refuses to eat. Or the expression on Sita Devi’s face when she asks “Tum Communist ho?” after Preetam makes an observation about the plight of people who have to sleep on footpaths.

As Arun Khopkar notes in his book Guru Dutt: A Tragedy in Three Acts, Dutt often did unusual things with song sequences to incorporate them into the narrative. There are some notable instances in Mr and Mrs 55. Preetam doesn’t speak at all in his first two scenes, and the first time we see his lips move it is when he abruptly breaks into song in Mohammed Rafi’s voice (“Dil par hua aisa jadoo”). Later, the superb “Jaane kahaan mera jigar gaya ji” begins with Johnny Walker briskly picking up the phone as if he is about to report a theft, and then singing into it. And near the film’s end, two versions of the same song are wonderfully integrated into two separate situations.

For Madhubala

A critic once said of Marilyn Monroe that she was often livelier in still images than in moving ones – a glib remark that undermines what a fine comic performer Monroe was. I can imagine someone saying something similar for Madhubala, and again, it would be wrong. Madhubala isn’t as good in Mr and Mrs 55 as she was in, say, Chalti ka Naam Gaadi (it’s so much more fun playing the foil with a Kishore Kumar!), but she’s still warm and fun. Divested of the terrible burden of being our Most Ethereal Actress, she shows many dimensions to her personality, including the ability to send herself up or look silly if required.

For the subtle movement between a happy-go-lucky tone and a more cautionary one

The narrative arc shifts from a breezy celebration of modernity – young people flirting and bantering at tennis clubs and swimming pools, Sita Devi celebrating the passing of the Divorce Bill, which will give Indian women more freedom – to a more conservative, tradition-based outlook that goes something like: Settle down into matrimony, young people! And oh, women, your greatest fulfilment will come from looking after your house.

This movement is reflected in the changing look and sound of the film. In the early scenes, there are many Hollywood influences: the genre itself (screwball comedy complete with a “meet cute” and many misunderstandings); the famous zither theme from The Third Man, which plays from a music box in Anita’s house; Anita reading a magazine with Gregory Peck on the cover. But in the final third, where things get more serious, not only does the tone become more recognisably overwrought, like a regular Hindi film of the period, but the use of music too – in songs such as “Preetam Aan Milo” – has a more classical, rooted feel than the early numbers like “Thandi Hawa Kaali Ghata”.

Progressive viewers of today will cringe a little at some of the later scenes – or perhaps say, with a rueful shake of the head, “Well, that’s how people thought in those less enlightened times.” Personally, I would have preferred it if the film hadn’t turned Sita Devi into an out-and-out antagonist at the end. As Pawar plays her, she certainly has many likable qualities in the early scenes, but the film eventually gives her short shrift by unfavourably placing her in opposition to Preetam’s heavily domesticated and self-sacrificing bhabhi.

Progressive viewers of today will cringe a little at some of the later scenes – or perhaps say, with a rueful shake of the head, “Well, that’s how people thought in those less enlightened times.” Personally, I would have preferred it if the film hadn’t turned Sita Devi into an out-and-out antagonist at the end. As Pawar plays her, she certainly has many likable qualities in the early scenes, but the film eventually gives her short shrift by unfavourably placing her in opposition to Preetam’s heavily domesticated and self-sacrificing bhabhi.

Even so, it would be reductive to say that the film is making a plea for women to be doormats. Both the carefree view and the home-bound one are accommodated in the narrative, and what one mostly remembers when all is done are the lighter moments. (Even the last shot has four young people skipping away from the camera!) The love between Anita and Preetam is organic and believable, as are the little displays of petulance or silliness that both engage in at different times – the impression one is left with is that of a relationship between equals. Which, again, is more than can be said about Guru Dutt’s martyred romances in his more “serious” films.

--------------------------------------

[Earlier Film Companion Flashback pieces are here]

--------------------

Title: Mr and Mrs 55

Director: Guru Dutt

Year: 1955

Cast: Madhubala, Guru Dutt, Lalita Pawar, Johnny Walker

Why you should watch it:

Why you should watch it:Because it’s Guru Dutt Lite (but points the way forward to his more personal work)

A confession: though I admire the major Guru Dutt films – the grandly dramatic ones, Pyaasa and Kaagaz ke Phool – and especially the individual elements that make them great (camerawork, music, lyrics, Waheeda Rehman), I am sidestepping them in this column. Part of this has to do with my reservations about Guru Dutt the actor when he is playing an overtly serious, sympathy-seeking part.

At the same time, Dutt’s earliest ventures into directing – such as Baazi and Jaal – don’t have enough of his distinct authorial personality. A fine middle ground can be discovered in Mr and Mrs 55, which has a charming performance by Dutt the actor and solid contributions by some of his most important collaborators – notably writer Abrar Alvi and cinematographer VK Murthy – while being both a romantic comedy and a (mildly pedantic) social statement.

At the same time, Dutt’s earliest ventures into directing – such as Baazi and Jaal – don’t have enough of his distinct authorial personality. A fine middle ground can be discovered in Mr and Mrs 55, which has a charming performance by Dutt the actor and solid contributions by some of his most important collaborators – notably writer Abrar Alvi and cinematographer VK Murthy – while being both a romantic comedy and a (mildly pedantic) social statement. And it even has a key Guru Dutt motif, which would be seen in his two iconic tragedies later in the decade – the theme of the artist in the gutter, impoverished and trampled on – but treated with lightness in this film. Dutt plays an unemployed cartoonist named Preetam, dependent for money and accommodation on his reporter friend Johnny (the wonderful Johnny Walker, who, you may recall, was also the rescuer-in-chief in Pyaasa). Then he meets the heiress Anita (Madhubala) as well as her aunt Sita Devi – a man-hating firebrand feminist, played by the great Lalita Pawar – who wants Anita to get married so she can get her inheritance (followed quickly by a divorce). Preetam is hired to be the temporary husband, but meanwhile he and Anita are falling in and out of love with each other.

For the sharp writing, the general air of zaniness… and RK Laxman

The film’s opening credits combine an image that could easily have come out of a Hollywood classic like The Philadelphia Story (a newspaper headline reads “Husband of Heiress Admits Infidelity”) with the work of a celebrated Indian cartoonist: RK Laxman, who did a very funny drawing specifically for the film (it shows the authoritarian Sita Devi riding a chariot pulled by Preetam and Anita).

The wacky tone persists for much of the film. Alvi’s dialogues sparkle, especially in the more lighthearted first half where we see professionals like doctors and lawyers – such solemn characters in other films of the time – behaving somewhat like Groucho Marx. Take the hilarious scene where a sad-looking physician examines the unwell Preetam and then has a surreal conversation with Johnny, shaking his head at the plight of this BA Pass cartoonist who only has a single pair of trousers. Or the one where an impish lawyer annoys Sita Devi while she tries to discuss the terms of her brother’s will.

The wacky tone persists for much of the film. Alvi’s dialogues sparkle, especially in the more lighthearted first half where we see professionals like doctors and lawyers – such solemn characters in other films of the time – behaving somewhat like Groucho Marx. Take the hilarious scene where a sad-looking physician examines the unwell Preetam and then has a surreal conversation with Johnny, shaking his head at the plight of this BA Pass cartoonist who only has a single pair of trousers. Or the one where an impish lawyer annoys Sita Devi while she tries to discuss the terms of her brother’s will. Among the many other little moments, I love the scene where a non-nonsense nanny remarks “Hamaaray zamaanay mein prem karte thay khaana khaakay, bhookhe pet nahin” when a lovelorn Anita refuses to eat. Or the expression on Sita Devi’s face when she asks “Tum Communist ho?” after Preetam makes an observation about the plight of people who have to sleep on footpaths.

As Arun Khopkar notes in his book Guru Dutt: A Tragedy in Three Acts, Dutt often did unusual things with song sequences to incorporate them into the narrative. There are some notable instances in Mr and Mrs 55. Preetam doesn’t speak at all in his first two scenes, and the first time we see his lips move it is when he abruptly breaks into song in Mohammed Rafi’s voice (“Dil par hua aisa jadoo”). Later, the superb “Jaane kahaan mera jigar gaya ji” begins with Johnny Walker briskly picking up the phone as if he is about to report a theft, and then singing into it. And near the film’s end, two versions of the same song are wonderfully integrated into two separate situations.

For Madhubala

A critic once said of Marilyn Monroe that she was often livelier in still images than in moving ones – a glib remark that undermines what a fine comic performer Monroe was. I can imagine someone saying something similar for Madhubala, and again, it would be wrong. Madhubala isn’t as good in Mr and Mrs 55 as she was in, say, Chalti ka Naam Gaadi (it’s so much more fun playing the foil with a Kishore Kumar!), but she’s still warm and fun. Divested of the terrible burden of being our Most Ethereal Actress, she shows many dimensions to her personality, including the ability to send herself up or look silly if required.

For the subtle movement between a happy-go-lucky tone and a more cautionary one

The narrative arc shifts from a breezy celebration of modernity – young people flirting and bantering at tennis clubs and swimming pools, Sita Devi celebrating the passing of the Divorce Bill, which will give Indian women more freedom – to a more conservative, tradition-based outlook that goes something like: Settle down into matrimony, young people! And oh, women, your greatest fulfilment will come from looking after your house.

This movement is reflected in the changing look and sound of the film. In the early scenes, there are many Hollywood influences: the genre itself (screwball comedy complete with a “meet cute” and many misunderstandings); the famous zither theme from The Third Man, which plays from a music box in Anita’s house; Anita reading a magazine with Gregory Peck on the cover. But in the final third, where things get more serious, not only does the tone become more recognisably overwrought, like a regular Hindi film of the period, but the use of music too – in songs such as “Preetam Aan Milo” – has a more classical, rooted feel than the early numbers like “Thandi Hawa Kaali Ghata”.

Progressive viewers of today will cringe a little at some of the later scenes – or perhaps say, with a rueful shake of the head, “Well, that’s how people thought in those less enlightened times.” Personally, I would have preferred it if the film hadn’t turned Sita Devi into an out-and-out antagonist at the end. As Pawar plays her, she certainly has many likable qualities in the early scenes, but the film eventually gives her short shrift by unfavourably placing her in opposition to Preetam’s heavily domesticated and self-sacrificing bhabhi.

Progressive viewers of today will cringe a little at some of the later scenes – or perhaps say, with a rueful shake of the head, “Well, that’s how people thought in those less enlightened times.” Personally, I would have preferred it if the film hadn’t turned Sita Devi into an out-and-out antagonist at the end. As Pawar plays her, she certainly has many likable qualities in the early scenes, but the film eventually gives her short shrift by unfavourably placing her in opposition to Preetam’s heavily domesticated and self-sacrificing bhabhi.Even so, it would be reductive to say that the film is making a plea for women to be doormats. Both the carefree view and the home-bound one are accommodated in the narrative, and what one mostly remembers when all is done are the lighter moments. (Even the last shot has four young people skipping away from the camera!) The love between Anita and Preetam is organic and believable, as are the little displays of petulance or silliness that both engage in at different times – the impression one is left with is that of a relationship between equals. Which, again, is more than can be said about Guru Dutt’s martyred romances in his more “serious” films.

--------------------------------------

[Earlier Film Companion Flashback pieces are here]

Published on March 27, 2019 18:44

March 19, 2019

The "anyways" conundrum

Here's something that puzzled me while I was reading a collection of Richard Matheson’s short stories.

Here's something that puzzled me while I was reading a collection of Richard Matheson’s short stories. Most grammar-pedants of my generation will agree that “anyways” — a corruption of “anyway”, and widely used by millennials and other mentally feeble groups — is an evil word. Also a rare case of a word or phrase being turned into “cool”-sounding slang by making it longer rather than shorter. (I’m sure it will soon be legitimised by the Oxford English Dictionary — because language “evolves” etc etc — and then the joke will be on us; but that’s another matter.)

Thing is, I was also certain that “anyways" was a recent creation: the first time I recall hearing it was in glossy Hindi films of the early 2000s where people like Sunil Shetty and Celina Jaitley would say it to each other while wearing sunglasses and cavorting on yachts. (Just conveying an impression, not saying there was exactly such a film.) For some reason it also felt like a particularly Indian mistake, like our famous habit of using a singular noun rather than a plural one at the end of “one of the…” or “one of my…”

But now I have found at least seven or eight occurrences of “anyways” in separate stories — mostly written between the 1950s and the 1960s — in this Richard Matheson anthology. In suspense classics like “Duel” (which was made into a super film by the young Steven Spielberg), “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet”, "Shipshape Home" and “No Such Thing as a Vampire”. It’s clear that Matheson routinely used the word, and not just in quoted speech.

Having read a lot of American and British genre/pulp writing from the 1920s through the 1960s, I can’t offhand recall other instances of this usage. Also, I rate Matheson a lot higher than many of the other “pure pulp” writers who wrote mainly for the cheapest magazines of their day, and much of whose work has not endured. (Read Matheson’s short story “The Doll That Does Everything” for a sense of the brilliantly zany and bold linguistic flourishes he could pull off when it suited a situation.) So it felt even stranger that his work should contain this satanic nonword.

Anyone who has come across other such cases in 20th century literature?

P.S. Researching, I learnt that “anyways” is a modification of “anywise”, which was used as far back as the 13th century. But it still feels like the current, slang-ish, 21st century version has a different provenance. It conjures up the image of young people, too lazy or privileged to complete a sentence without a servant to help them do it, curled up on a beanbag in Cafe Coffee Day, staring into their phones and thinking “What’s the point of life anyways?"

Published on March 19, 2019 02:57

March 16, 2019

On Kundan Shah, Paigham, and Vyjayanthimala as the comic foil

Ten years ago this week, I visited Kundan Shah’s Bandra office for the first of a series of conversations for the Jaane bhi do Yaaro book. Kundan gave me a lot of his time (over the course of a few meetings in March 2009, then another few in May) and I have many transcripts (much of it went into the book, obviously, but there are a few others too). The one below is an observation about a lighthearted scene in the 1959 Dilip Kumar-Vyjayanthimala-starrer Paigham:

"I remember one or two things that really impressed me about Paigham. One scene was Dilip Kumar’s introduction – he doesn’t have a place to stay so he’s sitting on a footpath under a lamppost and reading, I think it was Gandhi’s My Experiments with Truth. And then there’s a beautiful scene, which was copied later by Salim-Javed for the Amitabh film Dostana. Now this scene had nothing to do with the main narrative – you could easily have cut it and thrown it out. But it was a beautiful, static, fortuitous moment — like we say, 'It wasn’t planned, but it happened somehow.' Vyjayanthimala is in love with Dilip Kumar, and after singing a song together they are sitting and she casually asks, “There must have been other girls beside me in your life?” Dilip Kumar says, you are the only one. But she keeps saying there must have been some girl in school or college who fascinated you, and when she keeps probing he decides to invent a story about a girl and a fantastic love affair – a chance meeting, which develops into a major thing. And as he spins the story, Vyjayanthimala starts getting more and more jealous.

"I remember one or two things that really impressed me about Paigham. One scene was Dilip Kumar’s introduction – he doesn’t have a place to stay so he’s sitting on a footpath under a lamppost and reading, I think it was Gandhi’s My Experiments with Truth. And then there’s a beautiful scene, which was copied later by Salim-Javed for the Amitabh film Dostana. Now this scene had nothing to do with the main narrative – you could easily have cut it and thrown it out. But it was a beautiful, static, fortuitous moment — like we say, 'It wasn’t planned, but it happened somehow.' Vyjayanthimala is in love with Dilip Kumar, and after singing a song together they are sitting and she casually asks, “There must have been other girls beside me in your life?” Dilip Kumar says, you are the only one. But she keeps saying there must have been some girl in school or college who fascinated you, and when she keeps probing he decides to invent a story about a girl and a fantastic love affair – a chance meeting, which develops into a major thing. And as he spins the story, Vyjayanthimala starts getting more and more jealous.

Now the thing here is that she has to play the comic foil – and if your foil is not working the comedy can fall flat. There’s also a famous scene in Pyaar Kiye Jaa where Mehmood is narrating the script of a film he wants to make, Mehmood is using all the tricks at his disposal, but the scene wouldn’t have worked if Om Prakash hadn’t given the proper reactions at the right time. In comedy, it often looks like one person is doing the main work but the other person is equally important. Even Amitabh can't carry a whole comic scene on his own shoulders. When this Paigham scene was redone in Dostana, it fell flat because Zeenat Aman couldn’t play the foil the way Vyjayanthimala did."

Note what Kundan says about how the scene, though one of the best things in the film, could easily be “thrown out" since it had nothing to do with the main narrative. This is true of many of the great serendipitous (or “inessential”) moments in cinema — so many of them retain their vitality long after the film as a whole has become jaded.

In fact, watching Paigham on Amazon Prime recently (a good print), I found this was exactly what had been done: the scene was treated as inconsequential and ineptly shortened. (Vyjayanthimala asks Dilip Kumar if he had ever sat with another girl the way he was sitting with her, and he replies “ISS tarah? Nahin”, and that’s it - abrupt cut to the next scene. Makes no sense.) Luckily the full version is on YouTube, though not in a good print.

----------------------

[Here's a tribute to Kundan I wrote a little over a year ago, after his untimely passing]

"I remember one or two things that really impressed me about Paigham. One scene was Dilip Kumar’s introduction – he doesn’t have a place to stay so he’s sitting on a footpath under a lamppost and reading, I think it was Gandhi’s My Experiments with Truth. And then there’s a beautiful scene, which was copied later by Salim-Javed for the Amitabh film Dostana. Now this scene had nothing to do with the main narrative – you could easily have cut it and thrown it out. But it was a beautiful, static, fortuitous moment — like we say, 'It wasn’t planned, but it happened somehow.' Vyjayanthimala is in love with Dilip Kumar, and after singing a song together they are sitting and she casually asks, “There must have been other girls beside me in your life?” Dilip Kumar says, you are the only one. But she keeps saying there must have been some girl in school or college who fascinated you, and when she keeps probing he decides to invent a story about a girl and a fantastic love affair – a chance meeting, which develops into a major thing. And as he spins the story, Vyjayanthimala starts getting more and more jealous.

"I remember one or two things that really impressed me about Paigham. One scene was Dilip Kumar’s introduction – he doesn’t have a place to stay so he’s sitting on a footpath under a lamppost and reading, I think it was Gandhi’s My Experiments with Truth. And then there’s a beautiful scene, which was copied later by Salim-Javed for the Amitabh film Dostana. Now this scene had nothing to do with the main narrative – you could easily have cut it and thrown it out. But it was a beautiful, static, fortuitous moment — like we say, 'It wasn’t planned, but it happened somehow.' Vyjayanthimala is in love with Dilip Kumar, and after singing a song together they are sitting and she casually asks, “There must have been other girls beside me in your life?” Dilip Kumar says, you are the only one. But she keeps saying there must have been some girl in school or college who fascinated you, and when she keeps probing he decides to invent a story about a girl and a fantastic love affair – a chance meeting, which develops into a major thing. And as he spins the story, Vyjayanthimala starts getting more and more jealous.Now the thing here is that she has to play the comic foil – and if your foil is not working the comedy can fall flat. There’s also a famous scene in Pyaar Kiye Jaa where Mehmood is narrating the script of a film he wants to make, Mehmood is using all the tricks at his disposal, but the scene wouldn’t have worked if Om Prakash hadn’t given the proper reactions at the right time. In comedy, it often looks like one person is doing the main work but the other person is equally important. Even Amitabh can't carry a whole comic scene on his own shoulders. When this Paigham scene was redone in Dostana, it fell flat because Zeenat Aman couldn’t play the foil the way Vyjayanthimala did."

Note what Kundan says about how the scene, though one of the best things in the film, could easily be “thrown out" since it had nothing to do with the main narrative. This is true of many of the great serendipitous (or “inessential”) moments in cinema — so many of them retain their vitality long after the film as a whole has become jaded.

In fact, watching Paigham on Amazon Prime recently (a good print), I found this was exactly what had been done: the scene was treated as inconsequential and ineptly shortened. (Vyjayanthimala asks Dilip Kumar if he had ever sat with another girl the way he was sitting with her, and he replies “ISS tarah? Nahin”, and that’s it - abrupt cut to the next scene. Makes no sense.) Luckily the full version is on YouTube, though not in a good print.

----------------------

[Here's a tribute to Kundan I wrote a little over a year ago, after his untimely passing]

Published on March 16, 2019 22:57

March 15, 2019

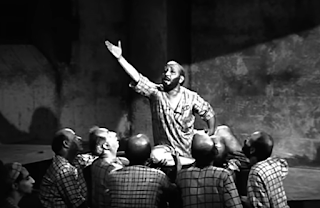

Flashback series: human pain and human comedy in Boot Polish (1954)

[the latest in my “flashback” recommendations for Film Companion]

Title: Boot Polish

Director: Prakash Arora (with some parts possibly ghost-directed by Raj Kapoor)

Year: 1954

Cast: Baby Naaz, Rattan Kumar, David Abraham, Chand Burke

Why you should watch it:

Because two child actors get top billing in a 1950s Hindi film… and earn it

Boot Polish is a Raj Kapoor film, produced by the celebrated actor-director, and by all accounts a project very close to his heart. But it was an atypical RK production. Here, the studio’s trademark images – Prithviraj Kapoor offering prayers, followed by the logo of Raj Kapoor and Nargis striking a romantic pose – yield to a less familiar sight: an illustration of two children hand in hand, pointing towards a dawning sun in the distance. The opening credits then give us the names of the child actors – Baby Naaz and Rattan Kumar – before the film’s title.

Which is as it should be, for the beating heart of this story is the love between orphaned siblings Bhola (Rattan) and Belu (Naaz), and their contrasting relationships with two adults in the slum where they grow up: the caring John Chacha (played by the splendid David Abraham), though a bootlegger himself, encourages them to be self-sufficient and earn money through honourable work; their shrew-like aunt Kamla Devi (Chand Burke) wants to exploit them by making them beg on the streets.

Which is as it should be, for the beating heart of this story is the love between orphaned siblings Bhola (Rattan) and Belu (Naaz), and their contrasting relationships with two adults in the slum where they grow up: the caring John Chacha (played by the splendid David Abraham), though a bootlegger himself, encourages them to be self-sufficient and earn money through honourable work; their shrew-like aunt Kamla Devi (Chand Burke) wants to exploit them by making them beg on the streets.

It’s almost inevitable, given this premise and the dominant tone of 1950s Hindi cinema, that there would be a few over-cutesy moments in the children’s (and adults’) performances. But there are also scenes that have the ring of heartbreaking truth, especially when it’s just the two of them on screen, trying to balance principles and ideals (in an innately unfair world) with the hunger in their bellies. Baby Naaz’s special distinction prize at the 1955 Cannes Film Festival was well deserved, even if there are times – especially in the musical sequences – where she comes across as a self-conscious, Shirley Temple-like movie star. She and Rattan work so well together that the film’s last 45 minutes, where they are separated by a series of contrived situations, feels like a relatively weak link, though one understands the narrative intent.

For its dualities: how it manages to be funny and very poignant at the same time; a gritty social document with location shooting, but also an effective big-studio melodrama

The children’s aunt is far from a sympathetic character (though the film does allow us to reflect that she too is driven by dire poverty), but there is a quirky early scene where, sending them out to beg, she hums the tune they should use to coerce money out of people’s pockets – and much to our amusement, for a few seconds this woman’s harsh voice becomes imbued with sweetness and melody. Beautiful music at the service of an ugly cause.

There are many other such bittersweet moments where human pain and human comedy run side by side. A crusty palm-reader tells Bhola “Tu saari umar jootay polish karega”, and the boy takes that as an uplifting prediction: I will become a big man, a shoe-shiner! There are sight gags such as the one where the siblings, in an early, amateurish attempt at polishing, stain a customer’s socks and quickly cover the mess with the man’s trousers. And there are social critiques, such as the comparison of the children’s sincerity with the smugness of a pandit who also gets money, but only because of his position as a religious leader. (A companion image to this one has John Chacha respectfully making the sign of the cross when he sees the shoe-polish and brush placed next to an image of Jesus Christ. For him, the tools of work are just as deserving of worship.)

Very early in Boot Polish, there is a stark close-up of the helpless faces of the children; at this point, you might expect a film from the Cinema Verite or neorealist schools (the title and theme are similar to Vittorio De Sica’s 1946 Shoeshine), but while those elements are present here, this is also very much a Hindi film in the melodramatic tradition. It is episodic and mixes tones, moving from a sad situation to a goofy song that links hair loss with drought. (This is “Lapak Jhapak Tu Aa Re Badarwa”, superbly sung by Manna Dey in Raga Adana.) You can carp about this if you’re looking for an organic narrative; personally, I think nearly all the individual parts work fine in their own right.

melodramatic tradition. It is episodic and mixes tones, moving from a sad situation to a goofy song that links hair loss with drought. (This is “Lapak Jhapak Tu Aa Re Badarwa”, superbly sung by Manna Dey in Raga Adana.) You can carp about this if you’re looking for an organic narrative; personally, I think nearly all the individual parts work fine in their own right.

For the 1950s conceit of the Beautiful New World or Nav Bharat

Only a few scenes are built around the boot-polishing profession (we learn, for example, that it’s pointless to go around asking people to have their shoes polished in rainy weather) – this is more of a stand-in for dignity of labour; for the idea that in the New India, no profession should be beneath contempt. “Aaj se hamaara Hindustan azaad hota hai!” the children exult when they save enough money to buy a shoe polish and brush. The film moves towards a too-tidy happy ending, but this also illustrates the thought that if you take even a small initiative in a hopeless situation, fate is likely to smile on you.

It isn’t like there are no pessimistic counterpoints. “Kidhar hai yeh nayi duniya? Hum kal bhi bhookha marta tha aur aaj bhi bhookha marta hai,” a jaded adult asks. But the thesis is that this first generation of children growing up in independent India will show the adults by example what the coming world should look like. Many other films made around the same time (like the hard-edged satire Mr Sampath, which imagines a utopian but highly improbable India of the future) were presenting such ideas from different perspectives. Boot Polish is among the sincerest and most hopeful of those films.

Because, at the height of his stardom as an actor-director, Raj Kapoor appears here for a few seconds – but doesn’t speak, or even open his eyes!

You’ll hear conflicting opinions about whether Kapoor ghost-directed chunks of this film (it is officially credited to his assistant Prakash Arora), but either way he didn’t cast himself in it. There is always something intriguing about a film by a major actor-director where he doesn’t appear onscreen (or doesn’t appear in his most familiar screen persona: like Charles Chaplin in Monsieur Verdoux). Kapoor does show up for a few seconds in his tramp costume, asleep on a train with a cigarette dangling from his mouth. A self-indulgent cameo, or a way of telling his audiences that he was taking a breather for a while and letting two children do the heavy lifting?

familiar screen persona: like Charles Chaplin in Monsieur Verdoux). Kapoor does show up for a few seconds in his tramp costume, asleep on a train with a cigarette dangling from his mouth. A self-indulgent cameo, or a way of telling his audiences that he was taking a breather for a while and letting two children do the heavy lifting?

---------------------------

Trivia: Boot Polish won the Best Film prize at the second edition of the Filmfare Awards, in 1955. Interestingly, the child actor Rattan Kumar – Bhola in this film – played prominent roles in each of the first three movies to win this prize. [The other two were Do Bigha Zamin (1954) and Jagriti (1956).]

[Earlier Flashback pieces are here]

Title: Boot Polish

Director: Prakash Arora (with some parts possibly ghost-directed by Raj Kapoor)

Year: 1954

Cast: Baby Naaz, Rattan Kumar, David Abraham, Chand Burke

Why you should watch it:

Because two child actors get top billing in a 1950s Hindi film… and earn it

Boot Polish is a Raj Kapoor film, produced by the celebrated actor-director, and by all accounts a project very close to his heart. But it was an atypical RK production. Here, the studio’s trademark images – Prithviraj Kapoor offering prayers, followed by the logo of Raj Kapoor and Nargis striking a romantic pose – yield to a less familiar sight: an illustration of two children hand in hand, pointing towards a dawning sun in the distance. The opening credits then give us the names of the child actors – Baby Naaz and Rattan Kumar – before the film’s title.

Which is as it should be, for the beating heart of this story is the love between orphaned siblings Bhola (Rattan) and Belu (Naaz), and their contrasting relationships with two adults in the slum where they grow up: the caring John Chacha (played by the splendid David Abraham), though a bootlegger himself, encourages them to be self-sufficient and earn money through honourable work; their shrew-like aunt Kamla Devi (Chand Burke) wants to exploit them by making them beg on the streets.

Which is as it should be, for the beating heart of this story is the love between orphaned siblings Bhola (Rattan) and Belu (Naaz), and their contrasting relationships with two adults in the slum where they grow up: the caring John Chacha (played by the splendid David Abraham), though a bootlegger himself, encourages them to be self-sufficient and earn money through honourable work; their shrew-like aunt Kamla Devi (Chand Burke) wants to exploit them by making them beg on the streets.It’s almost inevitable, given this premise and the dominant tone of 1950s Hindi cinema, that there would be a few over-cutesy moments in the children’s (and adults’) performances. But there are also scenes that have the ring of heartbreaking truth, especially when it’s just the two of them on screen, trying to balance principles and ideals (in an innately unfair world) with the hunger in their bellies. Baby Naaz’s special distinction prize at the 1955 Cannes Film Festival was well deserved, even if there are times – especially in the musical sequences – where she comes across as a self-conscious, Shirley Temple-like movie star. She and Rattan work so well together that the film’s last 45 minutes, where they are separated by a series of contrived situations, feels like a relatively weak link, though one understands the narrative intent.

For its dualities: how it manages to be funny and very poignant at the same time; a gritty social document with location shooting, but also an effective big-studio melodrama

The children’s aunt is far from a sympathetic character (though the film does allow us to reflect that she too is driven by dire poverty), but there is a quirky early scene where, sending them out to beg, she hums the tune they should use to coerce money out of people’s pockets – and much to our amusement, for a few seconds this woman’s harsh voice becomes imbued with sweetness and melody. Beautiful music at the service of an ugly cause.

There are many other such bittersweet moments where human pain and human comedy run side by side. A crusty palm-reader tells Bhola “Tu saari umar jootay polish karega”, and the boy takes that as an uplifting prediction: I will become a big man, a shoe-shiner! There are sight gags such as the one where the siblings, in an early, amateurish attempt at polishing, stain a customer’s socks and quickly cover the mess with the man’s trousers. And there are social critiques, such as the comparison of the children’s sincerity with the smugness of a pandit who also gets money, but only because of his position as a religious leader. (A companion image to this one has John Chacha respectfully making the sign of the cross when he sees the shoe-polish and brush placed next to an image of Jesus Christ. For him, the tools of work are just as deserving of worship.)

Very early in Boot Polish, there is a stark close-up of the helpless faces of the children; at this point, you might expect a film from the Cinema Verite or neorealist schools (the title and theme are similar to Vittorio De Sica’s 1946 Shoeshine), but while those elements are present here, this is also very much a Hindi film in the

melodramatic tradition. It is episodic and mixes tones, moving from a sad situation to a goofy song that links hair loss with drought. (This is “Lapak Jhapak Tu Aa Re Badarwa”, superbly sung by Manna Dey in Raga Adana.) You can carp about this if you’re looking for an organic narrative; personally, I think nearly all the individual parts work fine in their own right.

melodramatic tradition. It is episodic and mixes tones, moving from a sad situation to a goofy song that links hair loss with drought. (This is “Lapak Jhapak Tu Aa Re Badarwa”, superbly sung by Manna Dey in Raga Adana.) You can carp about this if you’re looking for an organic narrative; personally, I think nearly all the individual parts work fine in their own right. For the 1950s conceit of the Beautiful New World or Nav Bharat

Only a few scenes are built around the boot-polishing profession (we learn, for example, that it’s pointless to go around asking people to have their shoes polished in rainy weather) – this is more of a stand-in for dignity of labour; for the idea that in the New India, no profession should be beneath contempt. “Aaj se hamaara Hindustan azaad hota hai!” the children exult when they save enough money to buy a shoe polish and brush. The film moves towards a too-tidy happy ending, but this also illustrates the thought that if you take even a small initiative in a hopeless situation, fate is likely to smile on you.

It isn’t like there are no pessimistic counterpoints. “Kidhar hai yeh nayi duniya? Hum kal bhi bhookha marta tha aur aaj bhi bhookha marta hai,” a jaded adult asks. But the thesis is that this first generation of children growing up in independent India will show the adults by example what the coming world should look like. Many other films made around the same time (like the hard-edged satire Mr Sampath, which imagines a utopian but highly improbable India of the future) were presenting such ideas from different perspectives. Boot Polish is among the sincerest and most hopeful of those films.

Because, at the height of his stardom as an actor-director, Raj Kapoor appears here for a few seconds – but doesn’t speak, or even open his eyes!

You’ll hear conflicting opinions about whether Kapoor ghost-directed chunks of this film (it is officially credited to his assistant Prakash Arora), but either way he didn’t cast himself in it. There is always something intriguing about a film by a major actor-director where he doesn’t appear onscreen (or doesn’t appear in his most

familiar screen persona: like Charles Chaplin in Monsieur Verdoux). Kapoor does show up for a few seconds in his tramp costume, asleep on a train with a cigarette dangling from his mouth. A self-indulgent cameo, or a way of telling his audiences that he was taking a breather for a while and letting two children do the heavy lifting?

familiar screen persona: like Charles Chaplin in Monsieur Verdoux). Kapoor does show up for a few seconds in his tramp costume, asleep on a train with a cigarette dangling from his mouth. A self-indulgent cameo, or a way of telling his audiences that he was taking a breather for a while and letting two children do the heavy lifting?---------------------------

Trivia: Boot Polish won the Best Film prize at the second edition of the Filmfare Awards, in 1955. Interestingly, the child actor Rattan Kumar – Bhola in this film – played prominent roles in each of the first three movies to win this prize. [The other two were Do Bigha Zamin (1954) and Jagriti (1956).]

[Earlier Flashback pieces are here]

Published on March 15, 2019 03:36

March 8, 2019

His girl Friday: Sanjeev Kumar and the ‘computer’ in Trishul

[The latest in my “One Moment Please” columns for The Hindu is about an economical, unobtrusive little moment in a larger-than-life film]

------------------------

Watching the 1978 Trishul again after many years, a short, seemingly mundane scene caught my attention. It’s the one where we are introduced to the middle-aged version of the businessman RK Gupta, played by Sanjeev Kumar, and his superbly resourceful secretary Geeta (Raakhee).