Jai Arjun Singh's Blog, page 40

April 21, 2018

Still laughing after all these years

[My latest Mint Lounge column, on two comedies that turn 50 this year]

--------------------------

In one of the funnier scenes in the 1968 Sadhu aur Shaitan, a taxi driver named Bajrang (Mehmood) is told by a passenger (Ashok Kumar in a terrific cameo) that he should be proud of being from the same land as “that great hero Prithviraj”. The allusion is to the king Prithviraj Chauhan, but Bajrang hasn’t even heard of him and instead thinks of the actor Prithviraj Kapoor.

In one of the funnier scenes in the 1968 Sadhu aur Shaitan, a taxi driver named Bajrang (Mehmood) is told by a passenger (Ashok Kumar in a terrific cameo) that he should be proud of being from the same land as “that great hero Prithviraj”. The allusion is to the king Prithviraj Chauhan, but Bajrang hasn’t even heard of him and instead thinks of the actor Prithviraj Kapoor.

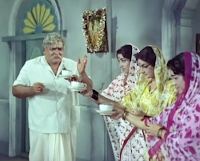

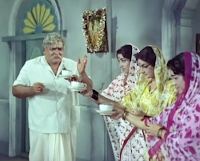

Ironically, another comedy from that year – Teen Bahuraniyan – has the real Prithviraj Kapoor as a patriarch who disapproves of the obsession with film stars. Little wonder, since this has brought disharmony to the old man’s house: his three sons and daughters-in-law are behaving like buffoons as they try to impress their new neighbor, the glamorous heroine Sheela Devi (played by Shashikala).

In the annals of Hindi-film comedy, 1968 is remembered mainly for Padosan, full of wacky performances not just by established funnymen (Kishore Kumar, Mehmood, Keshto Mukherjee) but also by a glamorous leading lady (Saira Banu) and a leading man (Sunil Dutt) who was more often associated with bland (or even stodgy) characters. The two films I mentioned above haven’t hit their half-century with the same panache, but they have some things in common with their more famous sibling: Teen Bahuraniyan involves an attractive “padosan” who lives in the house opposite and causes hearts (of men and women) to beat faster; Sadhu aur Shaitan has meaty roles for Mehmood and Kishore Kumar, whose scenes together are among the film’s high points.

But the differences are just as notable. One reason why Padosan has more lasting appeal than the other two films, I feel, is that it doesn’t have a serious bone in its body – it ratchets up the humour just when it starts to seem like things might be getting solemn, or that there might be a “message” around the corner.

In comparison, you can catch Teen Bahuraniyan and Sadhu aur Shaitan glancing about sheepishly like well-brought-up youngsters who are worried they are having too much fun. Teen Bahuraniyan flounders in its second half as it gets preachy about the neglect of household duties (and places disproportionate blame on the three flighty bahus as opposed to their equally silly husbands). Sadhu aur Shaitan is salvaged by a final act where Bajrang ferries passengers around, unaware that there’s a dead body in the back-seat, but before this too much time is spent on an establishing story about a good man being conned. Both films contain speeches about the importance of honesty and hard work over status anxiety or wealth-collection. Don’t give us money, give us love, two children sing to Lord Krishna in Sadhu aur Shaitan’s opening scene. Our house has two birds in it – one is love, the other is peace of mind, croons the family in Teen Bahuraniyan.

It can be a mistake to over-analyse or dissect comedy, but to look at these three films together is to also see how the staging of a little moment can make a difference; how holding a shot a second longer than necessary can make what might have been a delightful throwaway gesture seem forced and underlined; and how even loud, unsubtle comedy depends for its effectiveness on the quality of the acting and writing. Kishore Kumar, for instance, had the Groucho Marx-like ability to be over the top so wholeheartedly that the more lunatic he got, the more effective he was. Playing a thick-moustached Yamraj (God of Death) in a theatre production in Sadhu aur Shaitan, Kumar can have a viewer in convulsions just with an exaggerated booming voice that parodies mythological-film performances. On the other hand, actors like Rajendranath and Jagdeep (both of whom play key parts in Teen Bahuraniyan) have their strengths as physical comedians and mimics, but without the right direction or editing they are often loud without being especially funny.

It can be a mistake to over-analyse or dissect comedy, but to look at these three films together is to also see how the staging of a little moment can make a difference; how holding a shot a second longer than necessary can make what might have been a delightful throwaway gesture seem forced and underlined; and how even loud, unsubtle comedy depends for its effectiveness on the quality of the acting and writing. Kishore Kumar, for instance, had the Groucho Marx-like ability to be over the top so wholeheartedly that the more lunatic he got, the more effective he was. Playing a thick-moustached Yamraj (God of Death) in a theatre production in Sadhu aur Shaitan, Kumar can have a viewer in convulsions just with an exaggerated booming voice that parodies mythological-film performances. On the other hand, actors like Rajendranath and Jagdeep (both of whom play key parts in Teen Bahuraniyan) have their strengths as physical comedians and mimics, but without the right direction or editing they are often loud without being especially funny.

There are other lessons too. However outdated a film might look to our eyes, some of its worth can lie in the effect it had on its original audiences. When I spoke with writer-director Kundan Shah – helmsman of Jaane bhi do Yaaro – about his initiation into movie comedy, Teen Bahuraniyan was one of the first films he mentioned. This was before a DVD or YouTube print of this relatively obscure film was available, so I asked Shah what exactly had appealed to him. “I can’t explain such things,” he said a bit crabbily, “You have to experience it for yourself.”

Well, I did, eventually, and on the face of it there is little connection between Shah’s darkly edgy film – with humour masking angry social commentary – and an old-fashioned, home-bound comedy- drama. But look more closely at Teen Bahuraniyan and you see some wordplay and sight-gags that one can trace in Shah’s work: a scene where a woman moves in tune with her husband who is doing sit-ups while listening to her demands; Fourth Wall-breaking interludes where story updates are scribbled by children on a blackboard.

drama. But look more closely at Teen Bahuraniyan and you see some wordplay and sight-gags that one can trace in Shah’s work: a scene where a woman moves in tune with her husband who is doing sit-ups while listening to her demands; Fourth Wall-breaking interludes where story updates are scribbled by children on a blackboard.

Now, when I think of Ravi Baswani’s hysterics in Jaane bhi do Yaaro, or Pankaj Kapoor delivering deadpan monologues at the camera, I picture similar scenes featuring Rajendranath and company. Which is a bit disconcerting, but also a reminder that fifty-year-old films, including uneven ones, can cast long shadows.

----------------------------------

[Earlier piece on Padosan and Saira Banu here; and a tribute to the late Kundan Shah here]

--------------------------

In one of the funnier scenes in the 1968 Sadhu aur Shaitan, a taxi driver named Bajrang (Mehmood) is told by a passenger (Ashok Kumar in a terrific cameo) that he should be proud of being from the same land as “that great hero Prithviraj”. The allusion is to the king Prithviraj Chauhan, but Bajrang hasn’t even heard of him and instead thinks of the actor Prithviraj Kapoor.

In one of the funnier scenes in the 1968 Sadhu aur Shaitan, a taxi driver named Bajrang (Mehmood) is told by a passenger (Ashok Kumar in a terrific cameo) that he should be proud of being from the same land as “that great hero Prithviraj”. The allusion is to the king Prithviraj Chauhan, but Bajrang hasn’t even heard of him and instead thinks of the actor Prithviraj Kapoor. Ironically, another comedy from that year – Teen Bahuraniyan – has the real Prithviraj Kapoor as a patriarch who disapproves of the obsession with film stars. Little wonder, since this has brought disharmony to the old man’s house: his three sons and daughters-in-law are behaving like buffoons as they try to impress their new neighbor, the glamorous heroine Sheela Devi (played by Shashikala).

In the annals of Hindi-film comedy, 1968 is remembered mainly for Padosan, full of wacky performances not just by established funnymen (Kishore Kumar, Mehmood, Keshto Mukherjee) but also by a glamorous leading lady (Saira Banu) and a leading man (Sunil Dutt) who was more often associated with bland (or even stodgy) characters. The two films I mentioned above haven’t hit their half-century with the same panache, but they have some things in common with their more famous sibling: Teen Bahuraniyan involves an attractive “padosan” who lives in the house opposite and causes hearts (of men and women) to beat faster; Sadhu aur Shaitan has meaty roles for Mehmood and Kishore Kumar, whose scenes together are among the film’s high points.

But the differences are just as notable. One reason why Padosan has more lasting appeal than the other two films, I feel, is that it doesn’t have a serious bone in its body – it ratchets up the humour just when it starts to seem like things might be getting solemn, or that there might be a “message” around the corner.

In comparison, you can catch Teen Bahuraniyan and Sadhu aur Shaitan glancing about sheepishly like well-brought-up youngsters who are worried they are having too much fun. Teen Bahuraniyan flounders in its second half as it gets preachy about the neglect of household duties (and places disproportionate blame on the three flighty bahus as opposed to their equally silly husbands). Sadhu aur Shaitan is salvaged by a final act where Bajrang ferries passengers around, unaware that there’s a dead body in the back-seat, but before this too much time is spent on an establishing story about a good man being conned. Both films contain speeches about the importance of honesty and hard work over status anxiety or wealth-collection. Don’t give us money, give us love, two children sing to Lord Krishna in Sadhu aur Shaitan’s opening scene. Our house has two birds in it – one is love, the other is peace of mind, croons the family in Teen Bahuraniyan.

It can be a mistake to over-analyse or dissect comedy, but to look at these three films together is to also see how the staging of a little moment can make a difference; how holding a shot a second longer than necessary can make what might have been a delightful throwaway gesture seem forced and underlined; and how even loud, unsubtle comedy depends for its effectiveness on the quality of the acting and writing. Kishore Kumar, for instance, had the Groucho Marx-like ability to be over the top so wholeheartedly that the more lunatic he got, the more effective he was. Playing a thick-moustached Yamraj (God of Death) in a theatre production in Sadhu aur Shaitan, Kumar can have a viewer in convulsions just with an exaggerated booming voice that parodies mythological-film performances. On the other hand, actors like Rajendranath and Jagdeep (both of whom play key parts in Teen Bahuraniyan) have their strengths as physical comedians and mimics, but without the right direction or editing they are often loud without being especially funny.

It can be a mistake to over-analyse or dissect comedy, but to look at these three films together is to also see how the staging of a little moment can make a difference; how holding a shot a second longer than necessary can make what might have been a delightful throwaway gesture seem forced and underlined; and how even loud, unsubtle comedy depends for its effectiveness on the quality of the acting and writing. Kishore Kumar, for instance, had the Groucho Marx-like ability to be over the top so wholeheartedly that the more lunatic he got, the more effective he was. Playing a thick-moustached Yamraj (God of Death) in a theatre production in Sadhu aur Shaitan, Kumar can have a viewer in convulsions just with an exaggerated booming voice that parodies mythological-film performances. On the other hand, actors like Rajendranath and Jagdeep (both of whom play key parts in Teen Bahuraniyan) have their strengths as physical comedians and mimics, but without the right direction or editing they are often loud without being especially funny.There are other lessons too. However outdated a film might look to our eyes, some of its worth can lie in the effect it had on its original audiences. When I spoke with writer-director Kundan Shah – helmsman of Jaane bhi do Yaaro – about his initiation into movie comedy, Teen Bahuraniyan was one of the first films he mentioned. This was before a DVD or YouTube print of this relatively obscure film was available, so I asked Shah what exactly had appealed to him. “I can’t explain such things,” he said a bit crabbily, “You have to experience it for yourself.”

Well, I did, eventually, and on the face of it there is little connection between Shah’s darkly edgy film – with humour masking angry social commentary – and an old-fashioned, home-bound comedy-

drama. But look more closely at Teen Bahuraniyan and you see some wordplay and sight-gags that one can trace in Shah’s work: a scene where a woman moves in tune with her husband who is doing sit-ups while listening to her demands; Fourth Wall-breaking interludes where story updates are scribbled by children on a blackboard.

drama. But look more closely at Teen Bahuraniyan and you see some wordplay and sight-gags that one can trace in Shah’s work: a scene where a woman moves in tune with her husband who is doing sit-ups while listening to her demands; Fourth Wall-breaking interludes where story updates are scribbled by children on a blackboard. Now, when I think of Ravi Baswani’s hysterics in Jaane bhi do Yaaro, or Pankaj Kapoor delivering deadpan monologues at the camera, I picture similar scenes featuring Rajendranath and company. Which is a bit disconcerting, but also a reminder that fifty-year-old films, including uneven ones, can cast long shadows.

----------------------------------

[Earlier piece on Padosan and Saira Banu here; and a tribute to the late Kundan Shah here]

Published on April 21, 2018 00:44

April 18, 2018

"Your f*** is the problem" - on Unfreedom, a film about victims, bigots and sandcastles

[Did this short review of the film Unfreedom – censored and unreleased in India in 2015, now available on Netflix – for India Today]

-----------------------------

On a pristine beach, a large door stands by itself, one of a few elements and markers constituting a spare outdoor “house” – a space where two young women are free to make love, to build sandcastles like children, to get married around a sacred fire with only a large trident as witness; no prying or judging eyes.

It’s a surreal, dialogue-less scene, and if there had been more visual poetry like it in Raj Amit Kumar’s Unfreedom, this could have been a brilliant film. As it stands it has good intentions and earnest performances, but is stymied by excessive symbolism and on-the-nose dialogue that underlines each thought and action. Even that scene on the beach ultimately doesn’t trust the images to make the point – instead it ends with one of the women telling the camera: “This is our home. A home without walls. Just earth. Water. Fire. Love. It’s actually none of your business to pass judgement and rules and regulations.”

It’s a surreal, dialogue-less scene, and if there had been more visual poetry like it in Raj Amit Kumar’s Unfreedom, this could have been a brilliant film. As it stands it has good intentions and earnest performances, but is stymied by excessive symbolism and on-the-nose dialogue that underlines each thought and action. Even that scene on the beach ultimately doesn’t trust the images to make the point – instead it ends with one of the women telling the camera: “This is our home. A home without walls. Just earth. Water. Fire. Love. It’s actually none of your business to pass judgement and rules and regulations.”

Unfreedom cross-cuts between two unrelated stories, in New York and New Delhi. In the first, a young terrorist named Hussain (Bhanu Uday) kidnaps and tortures a liberal Muslim scholar (Victor Banerjee); in the second, the distressed Leela (Preeti Gupta) tries to break free from her controlling father (Adil Hussain) and rebuild a life with her former lover (Bhavani Lee).

These narratives examine different forms of intolerance, and the many ways in which people can be caught in a continuum of innocence, complicity and guilt. Oppression and conditioning paint them into corners, leading them into degrees of extremist behaviour: a boy who watched his family massacred goes on to perpetuate a cycle of violence himself; a woman is so haunted by social expectations that while trying to assert her sexual autonomy, she also insists on marrying her lover (even if the latter is reluctant to enter a full-fledged commitment). When society curtails freedoms – to love in the way one needs to; to follow (or not follow) a particular faith – the results can be explosive in unpredictable ways, with a victim in one context becoming a criminal in another.

These are worthy themes in themselves, but in exploring them the film often meanders, preaches and makes forced parallels between the stories: in the closing sequence, split screens are used to connect dots – right down to showing characters similarly framed or performing similar actions – but this is reductive and misleading. Some of the characters feel like caricatures too (take the glowering, xenophobic morality-keeper telling Sakhi when she uses the F-word, “That is the problem. Your fuck is the problem”) but this is a point more open to argument; real-world bigotry and fanaticism demonstrates that the line between “realistic” and “stereotyped” is always blurred.

In any case, conversations about the film’s merits or demerits are likely to take a back-seat to the controversy surrounding it. In 2015, Unfreedom went unreleased because the censor board, worried by its explicit treatment of homosexuality, felt it would “ignite unnatural passions”. There is something genuinely unsettling about this; it makes the censor-board chiefs seem like (slightly more benign) versions of the homophobic patriarchs who savagely assault the two lovers in one scene.

In any case, conversations about the film’s merits or demerits are likely to take a back-seat to the controversy surrounding it. In 2015, Unfreedom went unreleased because the censor board, worried by its explicit treatment of homosexuality, felt it would “ignite unnatural passions”. There is something genuinely unsettling about this; it makes the censor-board chiefs seem like (slightly more benign) versions of the homophobic patriarchs who savagely assault the two lovers in one scene.

As for the supposedly incendiary content: there is some discussion of religious fundamentalism, some provocative exchanges (including the “blasphemous” line “What the fuck does Allah have to do with this?”) but nothing we haven’t seen in other, subtler films. And there are nude scenes, a couple of which are clichéd and heavy-handed (woman exposed and defenceless, sobbing on her bathroom floor; bohemian artist sauntering naked through her studio apartment), while also giving the impression that Unfreedom is too glossy and prettified to do full justice to the horrors of its subject matter.

-----------------------------

On a pristine beach, a large door stands by itself, one of a few elements and markers constituting a spare outdoor “house” – a space where two young women are free to make love, to build sandcastles like children, to get married around a sacred fire with only a large trident as witness; no prying or judging eyes.

It’s a surreal, dialogue-less scene, and if there had been more visual poetry like it in Raj Amit Kumar’s Unfreedom, this could have been a brilliant film. As it stands it has good intentions and earnest performances, but is stymied by excessive symbolism and on-the-nose dialogue that underlines each thought and action. Even that scene on the beach ultimately doesn’t trust the images to make the point – instead it ends with one of the women telling the camera: “This is our home. A home without walls. Just earth. Water. Fire. Love. It’s actually none of your business to pass judgement and rules and regulations.”

It’s a surreal, dialogue-less scene, and if there had been more visual poetry like it in Raj Amit Kumar’s Unfreedom, this could have been a brilliant film. As it stands it has good intentions and earnest performances, but is stymied by excessive symbolism and on-the-nose dialogue that underlines each thought and action. Even that scene on the beach ultimately doesn’t trust the images to make the point – instead it ends with one of the women telling the camera: “This is our home. A home without walls. Just earth. Water. Fire. Love. It’s actually none of your business to pass judgement and rules and regulations.”Unfreedom cross-cuts between two unrelated stories, in New York and New Delhi. In the first, a young terrorist named Hussain (Bhanu Uday) kidnaps and tortures a liberal Muslim scholar (Victor Banerjee); in the second, the distressed Leela (Preeti Gupta) tries to break free from her controlling father (Adil Hussain) and rebuild a life with her former lover (Bhavani Lee).

These narratives examine different forms of intolerance, and the many ways in which people can be caught in a continuum of innocence, complicity and guilt. Oppression and conditioning paint them into corners, leading them into degrees of extremist behaviour: a boy who watched his family massacred goes on to perpetuate a cycle of violence himself; a woman is so haunted by social expectations that while trying to assert her sexual autonomy, she also insists on marrying her lover (even if the latter is reluctant to enter a full-fledged commitment). When society curtails freedoms – to love in the way one needs to; to follow (or not follow) a particular faith – the results can be explosive in unpredictable ways, with a victim in one context becoming a criminal in another.

These are worthy themes in themselves, but in exploring them the film often meanders, preaches and makes forced parallels between the stories: in the closing sequence, split screens are used to connect dots – right down to showing characters similarly framed or performing similar actions – but this is reductive and misleading. Some of the characters feel like caricatures too (take the glowering, xenophobic morality-keeper telling Sakhi when she uses the F-word, “That is the problem. Your fuck is the problem”) but this is a point more open to argument; real-world bigotry and fanaticism demonstrates that the line between “realistic” and “stereotyped” is always blurred.

In any case, conversations about the film’s merits or demerits are likely to take a back-seat to the controversy surrounding it. In 2015, Unfreedom went unreleased because the censor board, worried by its explicit treatment of homosexuality, felt it would “ignite unnatural passions”. There is something genuinely unsettling about this; it makes the censor-board chiefs seem like (slightly more benign) versions of the homophobic patriarchs who savagely assault the two lovers in one scene.

In any case, conversations about the film’s merits or demerits are likely to take a back-seat to the controversy surrounding it. In 2015, Unfreedom went unreleased because the censor board, worried by its explicit treatment of homosexuality, felt it would “ignite unnatural passions”. There is something genuinely unsettling about this; it makes the censor-board chiefs seem like (slightly more benign) versions of the homophobic patriarchs who savagely assault the two lovers in one scene. As for the supposedly incendiary content: there is some discussion of religious fundamentalism, some provocative exchanges (including the “blasphemous” line “What the fuck does Allah have to do with this?”) but nothing we haven’t seen in other, subtler films. And there are nude scenes, a couple of which are clichéd and heavy-handed (woman exposed and defenceless, sobbing on her bathroom floor; bohemian artist sauntering naked through her studio apartment), while also giving the impression that Unfreedom is too glossy and prettified to do full justice to the horrors of its subject matter.

Published on April 18, 2018 19:21

April 17, 2018

Churchill does punk, Padmaavat does praying mantises (on criticism and creativity)

[Here’s a little piece I wrote a couple of months ago, before I had to take a longish break from work. This appeared in The Hindu’s Sunday magazine]

---------------------------

There are two questions, closely linked, that I am often asked in film-criticism classes or at talks. One is if I harbor any screenplay-writing or novelistic aspirations. (A less polite version of the question goes “Aren’t all critics just failed authors/filmmakers?”) The other is that old chestnut about whether a reviewer let his imagination go berserk while analyzing a film, creating interpretations that the director (or screenwriter, or cinematographer) never intended.

Among the many possible responses, one can banter: no, I’m perfectly happy being a parasite or a eunuch, I sometimes say (alluding to two of the more vivid descriptions for critics), “And anyway, why add to an already-massive stockpile of bad novels and scripts?” Or one can get pedantic, hold forth on how “critic” and “artist” are not hermetically sealed categories and that a good piece of criticism (especially a long-form one) should ideally also be a good piece of writing.

But there are times when criticism and creativity collide in a more direct way, when a reviewer just has to impose his own personal screenplay on a film. This can happen if you’re sitting through something that isn’t at all working for you, and one way to stay sane is by hurriedly organizing a private show inside your head. Watching a trifle called Dhan Dhana Dhan Goal some years ago, about a bumbling NRI football team, I slipped into an alternate-world scenario where John Abraham’s nose – badly wounded during a match – acquired a personality of its own and ascended divinely into the clouds. I was also so bored by Jodha Akbar that I conjectured a story about the Mughal Empire being in crisis because the emperor and his new bride were weighed down by so much jewellery they were too tired to consummate their marriage.

At other times, a jarring scene might briefly take you outside a film that you are generally enjoying. This happened to me during viewings of two recent, high-profile films.

Late in Darkest Hour, Winston Churchill (played by Gary Oldman, even more heavily made up than in his role as the disfigured Mason Verger in Hannibal) is under pressure to broker peace with Hitler. Ducking into the London Underground, the Prime Minister spends some time with “regular people” to find out how they feel about getting into bed with Nazis. The resulting sequence – which prioritises a form of emotional realism over historical accuracy – has been trashed by many critics, but it’s possible to see it as a sort of opium-dream that Churchill is having in the depths of his despair; a way of building his confidence.

Think I’m stretching? Maybe. But because you can hardly take this scene at face value, it’s possible to go much further. One of its key elements – clearly intended to stir the modern viewer and make a point about the need for a democratic, egalitarian way of life – is a young black dandy in top hat and tails who completes an inspirational line of poetry for Churchill, appears to be in a romantic relationship with a white woman, and generally represents the hope of societal equality in a heavy-handed, anachronistic way.

elements – clearly intended to stir the modern viewer and make a point about the need for a democratic, egalitarian way of life – is a young black dandy in top hat and tails who completes an inspirational line of poetry for Churchill, appears to be in a romantic relationship with a white woman, and generally represents the hope of societal equality in a heavy-handed, anachronistic way.

But this dude and his clothes teleported me out of the film instantly, because I was reminded of the stoned dancer in the 1981 music video for the great Blondie song “Rapture” (which you must watch on YouTube) – and that in turn got me thinking of another famous Gary Oldman performance, as Sex Pistols frontman Sid Vicious in Sid and Nancy. My mind did return to Darkest Hour’s world of stuffy old Oxbridge-accented parliamentarians, but for a few beautiful moments I was in a space where Churchill and King George VI were boogeying together to punk rock as German bombs fell about them.

Sid and Nancy. My mind did return to Darkest Hour’s world of stuffy old Oxbridge-accented parliamentarians, but for a few beautiful moments I was in a space where Churchill and King George VI were boogeying together to punk rock as German bombs fell about them.

On a similar note, I mostly liked Padmaavat (a hard admission to make in the current climate where this film is widely seen as a steaming cauldron of misogyny, jingoism and Islamophobia), but then came the action sequence where one of Chittoor’s defenders continues slashing about for a bit after his head has parted ways from his torso and rolled out of frame.

The scene put me in mind of the grisly mating habits of that fascinating insect, the praying mantis. Briefly: the female sometimes bites off the male’s head mid-coitus, but his hindquarters continue to do their job for a while. (Then she gets annoyed and eats the rest of him, gathering important proteins for the baby mantises to come.)

This isn’t meant as a facile comparison. With all the narratives about Rajput heroism – something that Padmaavat cares deeply about – I feel the martyrdom of this unheralded creature, also in the name of preserving and perpetuating its species, deserves respect. In fact, given the recent video by writer and standup comedian Varun Grover about how the Padmaavat story was the result of one over-chatty parrot and four inefficient courtiers who failed to kill this bird, there may well be a parallel-universe version shot in the style of a wildlife feature with exotic creatures playing the key parts. An ostrich as Khilji? A peacock as Ratan Singh? Lemmings as the jauhar-committing women?

These would be good stories and I hope some of them get made. It’s the sort of thing we need more of, in a world of over-earnest films and angry responses to them.

---------------------------

There are two questions, closely linked, that I am often asked in film-criticism classes or at talks. One is if I harbor any screenplay-writing or novelistic aspirations. (A less polite version of the question goes “Aren’t all critics just failed authors/filmmakers?”) The other is that old chestnut about whether a reviewer let his imagination go berserk while analyzing a film, creating interpretations that the director (or screenwriter, or cinematographer) never intended.

Among the many possible responses, one can banter: no, I’m perfectly happy being a parasite or a eunuch, I sometimes say (alluding to two of the more vivid descriptions for critics), “And anyway, why add to an already-massive stockpile of bad novels and scripts?” Or one can get pedantic, hold forth on how “critic” and “artist” are not hermetically sealed categories and that a good piece of criticism (especially a long-form one) should ideally also be a good piece of writing.

But there are times when criticism and creativity collide in a more direct way, when a reviewer just has to impose his own personal screenplay on a film. This can happen if you’re sitting through something that isn’t at all working for you, and one way to stay sane is by hurriedly organizing a private show inside your head. Watching a trifle called Dhan Dhana Dhan Goal some years ago, about a bumbling NRI football team, I slipped into an alternate-world scenario where John Abraham’s nose – badly wounded during a match – acquired a personality of its own and ascended divinely into the clouds. I was also so bored by Jodha Akbar that I conjectured a story about the Mughal Empire being in crisis because the emperor and his new bride were weighed down by so much jewellery they were too tired to consummate their marriage.

At other times, a jarring scene might briefly take you outside a film that you are generally enjoying. This happened to me during viewings of two recent, high-profile films.

Late in Darkest Hour, Winston Churchill (played by Gary Oldman, even more heavily made up than in his role as the disfigured Mason Verger in Hannibal) is under pressure to broker peace with Hitler. Ducking into the London Underground, the Prime Minister spends some time with “regular people” to find out how they feel about getting into bed with Nazis. The resulting sequence – which prioritises a form of emotional realism over historical accuracy – has been trashed by many critics, but it’s possible to see it as a sort of opium-dream that Churchill is having in the depths of his despair; a way of building his confidence.

Think I’m stretching? Maybe. But because you can hardly take this scene at face value, it’s possible to go much further. One of its key

elements – clearly intended to stir the modern viewer and make a point about the need for a democratic, egalitarian way of life – is a young black dandy in top hat and tails who completes an inspirational line of poetry for Churchill, appears to be in a romantic relationship with a white woman, and generally represents the hope of societal equality in a heavy-handed, anachronistic way.

elements – clearly intended to stir the modern viewer and make a point about the need for a democratic, egalitarian way of life – is a young black dandy in top hat and tails who completes an inspirational line of poetry for Churchill, appears to be in a romantic relationship with a white woman, and generally represents the hope of societal equality in a heavy-handed, anachronistic way.But this dude and his clothes teleported me out of the film instantly, because I was reminded of the stoned dancer in the 1981 music video for the great Blondie song “Rapture” (which you must watch on YouTube) – and that in turn got me thinking of another famous Gary Oldman performance, as Sex Pistols frontman Sid Vicious in

Sid and Nancy. My mind did return to Darkest Hour’s world of stuffy old Oxbridge-accented parliamentarians, but for a few beautiful moments I was in a space where Churchill and King George VI were boogeying together to punk rock as German bombs fell about them.

Sid and Nancy. My mind did return to Darkest Hour’s world of stuffy old Oxbridge-accented parliamentarians, but for a few beautiful moments I was in a space where Churchill and King George VI were boogeying together to punk rock as German bombs fell about them. On a similar note, I mostly liked Padmaavat (a hard admission to make in the current climate where this film is widely seen as a steaming cauldron of misogyny, jingoism and Islamophobia), but then came the action sequence where one of Chittoor’s defenders continues slashing about for a bit after his head has parted ways from his torso and rolled out of frame.

The scene put me in mind of the grisly mating habits of that fascinating insect, the praying mantis. Briefly: the female sometimes bites off the male’s head mid-coitus, but his hindquarters continue to do their job for a while. (Then she gets annoyed and eats the rest of him, gathering important proteins for the baby mantises to come.)

This isn’t meant as a facile comparison. With all the narratives about Rajput heroism – something that Padmaavat cares deeply about – I feel the martyrdom of this unheralded creature, also in the name of preserving and perpetuating its species, deserves respect. In fact, given the recent video by writer and standup comedian Varun Grover about how the Padmaavat story was the result of one over-chatty parrot and four inefficient courtiers who failed to kill this bird, there may well be a parallel-universe version shot in the style of a wildlife feature with exotic creatures playing the key parts. An ostrich as Khilji? A peacock as Ratan Singh? Lemmings as the jauhar-committing women?

These would be good stories and I hope some of them get made. It’s the sort of thing we need more of, in a world of over-earnest films and angry responses to them.

Published on April 17, 2018 22:54

April 4, 2018

The Terror: a tale of two ships and the monstrous Arctic

[Did this short review of the new TV series The Terror for India Today. Have watched three episodes so far, and it has got me reading a great deal about the doomed Franklin expedition. More on which here]

[Did this short review of the new TV series The Terror for India Today. Have watched three episodes so far, and it has got me reading a great deal about the doomed Franklin expedition. More on which here]-------------------------

“Terror is signaling, Sir John,” someone says early in the new series The Terror . The words are innocuous in the given context (a ship’s captain is being alerted to a message from her companion ship) but they carry a portent – in much the same way that the title of the show’s second episode, “Gore”, could refer to a character’s name, but also signal what will happen to him.

Such wordplay is par for the course in a series that takes a real-life mystery – the 1845 disappearance of two Royal Navy ships, Erebus and Terror, in the Arctic – and infuses supernatural elements into it. So far, The Terror has only hinted at the latter (the first two episodes were available on Amazon Prime at the time of writing; the others will follow in weekly instalments). But it’s clear that this show, adapted from a Dan Simmons novel, will glide on thin ice as it balances creature-feature horror tropes with psychological tension and the restraint and authenticity required of a historical narrative.

What helps is the setting and the period – something that is evident from the many majestic shots of ice-crusted ships moving through an unfathomably large (and uncharted) Arctic desert. In this place, the line between “real” and “mystical” is very easily blurred, and even a rational mind can get spooked. This is conveyed very well through the grand bleakness of the visuals: men playing football on the ice after the two ships are stuck; a scene that cross-cuts between a postmortem on an unfortunate young sailor and a different sort of operation being conducted on a ship’s bowel. The cast includes those wonderful character actors Jared Harris (who was excellent as George VI in The Crown and as Lane Pryce in Mad Men) and Ciaran Hinds, as captains who try to be civil with each other but

can’t quite see eye to eye. And Marcus Fjellström’s effective, minatory score seems to evoke the Arctic wind groaning at these intruders, warning them to stay out of what they cannot understand.

can’t quite see eye to eye. And Marcus Fjellström’s effective, minatory score seems to evoke the Arctic wind groaning at these intruders, warning them to stay out of what they cannot understand. “This place wants us dead,” one character says to another. It’s a dramatic, shiver-inducing line that could come from a straightforward horror story – but it is also plausible here, since these men are facing the cold implacability of nature, seemingly impervious to their plans and conceits.

Is she really so detached, though? From our vantage point in 2018, knowing about global warming and the far-reaching effects of Victorian-era industrialization and exploration, the story of these doomed ships carries another resonance. It’s almost as if nature, knowing what we will do to the planet, is taking a form of pre-revenge by toying with these men for sport. The big scary horror-movie monster stalking them could just be one of her minions.

Published on April 04, 2018 03:35

March 28, 2018

Print the legend: David Niven at the Oscars

Having had to take a break from writing for a while, one way I’ve been distracting myself is by looking at old film-related footage and comparing them with the things I have read about the events in question. Consider David Niven’s best actor Oscar win for Separate Tables in 1959.

Niven’s The Moon’s a Balloon, and its companion piece Bring on the Empty Horses, were two of the funniest, most enjoyable film books I encountered in my early teens, and they still rank among my favourite pick-it-up-and-randomly-open-a-page reads. From his account of the Oscar ceremony:

No tripping, no sprawling (though quite possibly he was doing all that in his head) – just an elegant Brit cantering up the steps and then saying: “I’m so loaded down with good-luck charms I could hardly make it up the steps” (no pause after “loaded”, no roar of misunderstanding from the audience).

In his written account, Niven also neglected to mention the presence of John Wayne (somewhat hard to miss at 6 feet 4) on the stage. That isn’t such a big deal, but it may be relevant here to recall a famous line from a great film Wayne would star in a few years later: “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.”

Rereading The Moon’s a Balloon now, I wonder just how much else Niven embellished as he tried to be the PG Wodehouse of memoir writing. Perhaps, given that he was chronicling his years in a profession built around artifice, and his time in Hollywood the dream factory, he felt it would be apt to try some fantasy-making of his own.

Or maybe these books are just reminders of how unreliable our memories are, how we subconsciously create narratives about ourselves in our heads, until at some point they become "true" and What Really Happened is replaced by What Should Have Happened. Another win for poetic realism.

[More in this series soon]

Niven’s The Moon’s a Balloon, and its companion piece Bring on the Empty Horses, were two of the funniest, most enjoyable film books I encountered in my early teens, and they still rank among my favourite pick-it-up-and-randomly-open-a-page reads. From his account of the Oscar ceremony:

Irene Dunne was finally introduced and I carefully composed my generous-hearted-loser face, for she it was who would open the big white envelope […]Now compare the above description with what happens in this video (starting around the 50-second mark):

Such was my haste to get on that stage that I tripped up the steps and sprawled headlong. Another roar rent the air. Irene helped me up, gave me the Oscar, kissed me on the cheek, and left me alone with the microphone. I thought the least I could do was to explain my precipitous entrance, so I said “The reason I just fell down was…” I had intended to continue “…because I was so loaded with good-luck charms that I was top-heavy”. Unfortunately, I made an idiot pause after the word “loaded” and a third roar raised the roof.

I knew I could never top that, so I said no more on the subject, thereby establishing myself as the first self-confessed drunk to win the Academy Award.

No tripping, no sprawling (though quite possibly he was doing all that in his head) – just an elegant Brit cantering up the steps and then saying: “I’m so loaded down with good-luck charms I could hardly make it up the steps” (no pause after “loaded”, no roar of misunderstanding from the audience).

In his written account, Niven also neglected to mention the presence of John Wayne (somewhat hard to miss at 6 feet 4) on the stage. That isn’t such a big deal, but it may be relevant here to recall a famous line from a great film Wayne would star in a few years later: “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.”

Rereading The Moon’s a Balloon now, I wonder just how much else Niven embellished as he tried to be the PG Wodehouse of memoir writing. Perhaps, given that he was chronicling his years in a profession built around artifice, and his time in Hollywood the dream factory, he felt it would be apt to try some fantasy-making of his own.

Or maybe these books are just reminders of how unreliable our memories are, how we subconsciously create narratives about ourselves in our heads, until at some point they become "true" and What Really Happened is replaced by What Should Have Happened. Another win for poetic realism.

[More in this series soon]

Published on March 28, 2018 02:05

February 25, 2018

Travelers, platforms: recent depictions of vulnerable parents and headstrong children

[in my latest Mint Lounge column, thoughts on a lovely scene in the new film Love Per Square Foot]

----------------------------------------

In some of the busier, more detail-rich Hindi films of recent years, the supporting characters have been more compelling than the protagonists. I can’t think of many better examples of this than Anand Tiwari’s Love per Square Foot, a romantic comedy-drama released on Netflix earlier this month.

Taken as a whole, the film blew hot and cold for me. Despite the likable duo at its centre – Sanjay (Vicky Kaushal) and Karina (Angira Dhar), two bank employees who fall in love after making a joint deal to buy a flat – the narrative was long-winded and sometimes seemed like it was trying too hard to be cute. But this was partly made up for by some fine sequences involving a trio of veteran actors: Raghuvir Yadav and the real-life sisters Ratna Pathak Shah and Supriya Pathak.

One wonderfully delicate and moving scene is set during the retirement celebration of Sanjay’s father Bhaskar (Yadav), a railway employee who came to Mumbai thirty years earlier to be a singer but ended up in the much less glamorous profession of train announcer. This hasn’t killed the artist in the man, or his need for riyaaz: the first time we see him, at the film’s beginning, he is practicing on his harmonium, clearing his throat, testing the word “yaatri” (traveler). Now, in the retirement scene, Bhaskar makes a hesitant speech about train lines being like haath ki lakeer (palm lines) and how one might easily get on the wrong platform in life too; how announcers like him are like parents gently steering their children towards the right path (even as those children get impatient and complain).

One wonderfully delicate and moving scene is set during the retirement celebration of Sanjay’s father Bhaskar (Yadav), a railway employee who came to Mumbai thirty years earlier to be a singer but ended up in the much less glamorous profession of train announcer. This hasn’t killed the artist in the man, or his need for riyaaz: the first time we see him, at the film’s beginning, he is practicing on his harmonium, clearing his throat, testing the word “yaatri” (traveler). Now, in the retirement scene, Bhaskar makes a hesitant speech about train lines being like haath ki lakeer (palm lines) and how one might easily get on the wrong platform in life too; how announcers like him are like parents gently steering their children towards the right path (even as those children get impatient and complain).

In a room full of appreciative (if somewhat jaded-looking) colleagues, he then not only makes his last train announcement but is also coerced to sing a few lines of the classic song “Musafir hun yaaron” – and we see people on a platform, listening. The inner world of a peripheral character has come alive: Bhaskar has, very briefly, realised his dream of singing for a public (though the lyricism of a Gulzar-penned song is then followed by a mundane announcement about a Bandra train). At the same time, the words “na ghar hai, na thikaana” comment on the ongoing struggles of his son, who is trying to break away from his father by getting his own space in the big city.

Watching the scene, I was reminded of another, younger version of Yadav (one of our finest actors, though his career has had many starts and stops) – as the junkie Chillum, who lives and dies near the railway tracks, more often than not finding himself on the wrong path, in Mira Nair’s Salaam Bombay. But I was also reminded of how adept the “multiplex film” has become at depicting a certain sort of vulnerable parent – a character who might at first seem to exist in the narrative only as an obstacle or antagonist for the younger generation, but who has a hidden depth and a back-story, even when the film doesn’t overtly explore it.

In Love per Square Foot itself, Bhaskar isn’t the only such parent. Another strong scene has Karina’s mother, the chatty Mrs D’Souza (Ratna Pathak Shah), feeling wounded when her daughter gives her a lecture about wanting to be her own person – “not like you, dependent on your brother”. Oh no, you’ll never be me, the mother replies in a tone that combines hurt with sarcasm. You’re not capable of the sacrifices I made to bring you up.

In Love per Square Foot itself, Bhaskar isn’t the only such parent. Another strong scene has Karina’s mother, the chatty Mrs D’Souza (Ratna Pathak Shah), feeling wounded when her daughter gives her a lecture about wanting to be her own person – “not like you, dependent on your brother”. Oh no, you’ll never be me, the mother replies in a tone that combines hurt with sarcasm. You’re not capable of the sacrifices I made to bring you up.

It has generally been a good time for well-written and performed parental figures who get to both shape and passively comment on their children’s lives. Pankaj Tripathi and Seema Pahwa got deserved praise for their roles as the heroine’s fretting parents in Bareilly ki Barffi, but Tripathi also played a different, more sinister father – a real-estate developer whose life and actions cast a shadow over those of his children – in one of last year’s most underrated films, Shanker Raman’s Gurgaon.

Just as interesting is when the generational conflict plays out in ways where the viewer is left a little ambivalent. Without making sweeping statements about self-centred youngsters and their sacrificing parents, it seems to me that the arc of our socially conscious cinema – emphasizing progressiveness, self-actualisation, individual freedom – often stacks the cards in favour of the young and against the old. However, some of the best writing gives us people who might be innately tradition-bound but are also trying to understand new ways of living and thinking.

One of the most complex scenes along this vein occurred in Anurag Kashyap’s excellent Mukkabaaz , when Shravan (Vineet Kumar Singh) explodes at his father, who is questioning his decision to become a boxer. The scene – driven by Singh’s heartfelt performance and a script full of gems (“You are both zeroes,” Shravan rages at his parents, “How did you expect me to become an Aryabhatt?”) – seems to put us in the young man’s corner. And yet there is something about the sad-looking father’s expression as he sits there in his faded pullover, tries to rage back and comically mispronounces “passion” as “fashion”. He does eventually stand by his son, and you wonder if this “shunya” (zero) once had mad dreams of his own, how life ran roughshod over them – and how much the son owes, without realizing it, to his parents having gone for stability over passion.

----------------------------------------

In some of the busier, more detail-rich Hindi films of recent years, the supporting characters have been more compelling than the protagonists. I can’t think of many better examples of this than Anand Tiwari’s Love per Square Foot, a romantic comedy-drama released on Netflix earlier this month.

Taken as a whole, the film blew hot and cold for me. Despite the likable duo at its centre – Sanjay (Vicky Kaushal) and Karina (Angira Dhar), two bank employees who fall in love after making a joint deal to buy a flat – the narrative was long-winded and sometimes seemed like it was trying too hard to be cute. But this was partly made up for by some fine sequences involving a trio of veteran actors: Raghuvir Yadav and the real-life sisters Ratna Pathak Shah and Supriya Pathak.

One wonderfully delicate and moving scene is set during the retirement celebration of Sanjay’s father Bhaskar (Yadav), a railway employee who came to Mumbai thirty years earlier to be a singer but ended up in the much less glamorous profession of train announcer. This hasn’t killed the artist in the man, or his need for riyaaz: the first time we see him, at the film’s beginning, he is practicing on his harmonium, clearing his throat, testing the word “yaatri” (traveler). Now, in the retirement scene, Bhaskar makes a hesitant speech about train lines being like haath ki lakeer (palm lines) and how one might easily get on the wrong platform in life too; how announcers like him are like parents gently steering their children towards the right path (even as those children get impatient and complain).

One wonderfully delicate and moving scene is set during the retirement celebration of Sanjay’s father Bhaskar (Yadav), a railway employee who came to Mumbai thirty years earlier to be a singer but ended up in the much less glamorous profession of train announcer. This hasn’t killed the artist in the man, or his need for riyaaz: the first time we see him, at the film’s beginning, he is practicing on his harmonium, clearing his throat, testing the word “yaatri” (traveler). Now, in the retirement scene, Bhaskar makes a hesitant speech about train lines being like haath ki lakeer (palm lines) and how one might easily get on the wrong platform in life too; how announcers like him are like parents gently steering their children towards the right path (even as those children get impatient and complain). In a room full of appreciative (if somewhat jaded-looking) colleagues, he then not only makes his last train announcement but is also coerced to sing a few lines of the classic song “Musafir hun yaaron” – and we see people on a platform, listening. The inner world of a peripheral character has come alive: Bhaskar has, very briefly, realised his dream of singing for a public (though the lyricism of a Gulzar-penned song is then followed by a mundane announcement about a Bandra train). At the same time, the words “na ghar hai, na thikaana” comment on the ongoing struggles of his son, who is trying to break away from his father by getting his own space in the big city.

Watching the scene, I was reminded of another, younger version of Yadav (one of our finest actors, though his career has had many starts and stops) – as the junkie Chillum, who lives and dies near the railway tracks, more often than not finding himself on the wrong path, in Mira Nair’s Salaam Bombay. But I was also reminded of how adept the “multiplex film” has become at depicting a certain sort of vulnerable parent – a character who might at first seem to exist in the narrative only as an obstacle or antagonist for the younger generation, but who has a hidden depth and a back-story, even when the film doesn’t overtly explore it.

In Love per Square Foot itself, Bhaskar isn’t the only such parent. Another strong scene has Karina’s mother, the chatty Mrs D’Souza (Ratna Pathak Shah), feeling wounded when her daughter gives her a lecture about wanting to be her own person – “not like you, dependent on your brother”. Oh no, you’ll never be me, the mother replies in a tone that combines hurt with sarcasm. You’re not capable of the sacrifices I made to bring you up.

In Love per Square Foot itself, Bhaskar isn’t the only such parent. Another strong scene has Karina’s mother, the chatty Mrs D’Souza (Ratna Pathak Shah), feeling wounded when her daughter gives her a lecture about wanting to be her own person – “not like you, dependent on your brother”. Oh no, you’ll never be me, the mother replies in a tone that combines hurt with sarcasm. You’re not capable of the sacrifices I made to bring you up.It has generally been a good time for well-written and performed parental figures who get to both shape and passively comment on their children’s lives. Pankaj Tripathi and Seema Pahwa got deserved praise for their roles as the heroine’s fretting parents in Bareilly ki Barffi, but Tripathi also played a different, more sinister father – a real-estate developer whose life and actions cast a shadow over those of his children – in one of last year’s most underrated films, Shanker Raman’s Gurgaon.

Just as interesting is when the generational conflict plays out in ways where the viewer is left a little ambivalent. Without making sweeping statements about self-centred youngsters and their sacrificing parents, it seems to me that the arc of our socially conscious cinema – emphasizing progressiveness, self-actualisation, individual freedom – often stacks the cards in favour of the young and against the old. However, some of the best writing gives us people who might be innately tradition-bound but are also trying to understand new ways of living and thinking.

One of the most complex scenes along this vein occurred in Anurag Kashyap’s excellent Mukkabaaz , when Shravan (Vineet Kumar Singh) explodes at his father, who is questioning his decision to become a boxer. The scene – driven by Singh’s heartfelt performance and a script full of gems (“You are both zeroes,” Shravan rages at his parents, “How did you expect me to become an Aryabhatt?”) – seems to put us in the young man’s corner. And yet there is something about the sad-looking father’s expression as he sits there in his faded pullover, tries to rage back and comically mispronounces “passion” as “fashion”. He does eventually stand by his son, and you wonder if this “shunya” (zero) once had mad dreams of his own, how life ran roughshod over them – and how much the son owes, without realizing it, to his parents having gone for stability over passion.

Published on February 25, 2018 23:43

February 15, 2018

Ae ajnabi: a few of my favourite sad love songs (or break-up songs)

[Did this piece for Mint Lounge’s recent issue themed “love” – or “post-love”, I’m still not sure]

[Did this piece for Mint Lounge’s recent issue themed “love” – or “post-love”, I’m still not sure]-----------------------------------------------

When I think of sad love songs from old Hindi cinema, my mind turns to two 1960s classics that, in different ways, mislead a viewer. Watching “Dost Dost na Raha” on Chitrahaar without having seen the film it was from, Raj Kapoor’s epic melodrama Sangam, I thought the song was about the hero Sundar (Kapoor) having been betrayed by his lover Radha (Vyjayanthimala) and his buddy Gopal (Rajendra Kumar). The visuals underlined this: here was Sundar singing at a piano, looking heartbroken and sardonic in turn; behind him, the other two squirmed, their flashback-memories suggesting perfidy.

This interpretation turned out to be wrong: Sundar isn’t indicting his loved ones, he is just relating another friend’s tragic story. And though the lyrics make Radha and Gopal feel sheepish, they are the story’s real romantic couple and have nothing to be ashamed of. (Except, perhaps, that they have spent so much time indulging a whiny, masochistic man.)

Vyjayanthimala shows up again in Jewel Thief as Shalu, singing the plaintive “Rula ke gaya sapna”. When you first see this beautifully filmed nighttime scene – Shalu in the moonlight, Vinay (Dev Anand) rowing a boat while listening intently – you’ll assume she is mourning the broken romance that has been mentioned earlier in the story. But this is a thriller and the scene turns out to be a red herring, a clever exercise in misdirection.

Watched together, these two sequences also point to a difference between the sad love song that centres on the hero’s pain versus the one that focuses on the heroine’s: the former mode tends to be self-righteous and accusatory (remember the soaring “Dil ke jharokhe mein” from Brahmachari, with Shammi Kapoor’s steely gaze directed at Rajshree), while the latter is gentler, more about immersing oneself in the pleasure-pain of loss than in blaming the duplicitous other. Even the title song of Barsaat, so effectively reprised in the film’s closing scene – over the funeral pyre of a young woman who was abandoned by a playboy – expresses regret, “mil na sake haaye, mil na sake hum”, instead of hitting out.

This is, of course, a generalization, and, as with everything else in Hindi cinema, there are exceptions: take the lovely “O Saathi Re” scene from Muqaddar ka Sikandar, in which Sikander (Amitabh Bachchan), instead of going on about his unrequited love, pays tribute to the girl who reached out to him – as a friend – when no one else would. Or other scenes that blur gender lines, such as three wonderful songs that are primarily about a woman’s inner world

but are sung in a male voice: “Tum bin jeevan” from Bawarchi (with Kaifi Azmi’s lyrics including the lines “Baante koi kyun dukh mera / Apne aansu, apna hee daaman”); “Kai baar yun bhi dekha hai” from Rajnigandha; and Khamoshi’s haunting “Woh shaam kuch ajeeb thi” in which the singing is done by the Rajesh Khanna character but the scene’s focus is the great Waheeda Rehman, lost in the memory of an earlier love that has emotionally drained her.

but are sung in a male voice: “Tum bin jeevan” from Bawarchi (with Kaifi Azmi’s lyrics including the lines “Baante koi kyun dukh mera / Apne aansu, apna hee daaman”); “Kai baar yun bhi dekha hai” from Rajnigandha; and Khamoshi’s haunting “Woh shaam kuch ajeeb thi” in which the singing is done by the Rajesh Khanna character but the scene’s focus is the great Waheeda Rehman, lost in the memory of an earlier love that has emotionally drained her. The post-love (or interrupted-love) song encompasses many other forms and themes. There are tragic songs performed in the exalted mode (“Aaja re pardesi” from Madhumati, “Beqas pe karam kijiye” from Mughal-e Azam). There is judaai in the name of duty or social propriety (“Chalo ek baar phir se” in Gumrah), or through death (“Lagi aaj sawaan ki” from Chandni). There are rousing compositions that transcend their contexts (it’s possible to be stirred by Ismail Darbari’s “Tadap tadap ke iss dil” from Hum Di De Chuke Sanam even if you can’t work up sympathy for Salman Khan or Aishwarya Rai), and other rousing compositions that work brilliantly alongside the film’s visuals (“Ae ajnabi” from Dil Se).

In the 1970s and 1980s, the high emotional registers of the mainstream were balanced by the more muted approach of the so-called Middle Cinema, which didn’t deal with concepts like eternal soulmates but with the matter-of-fact possibility that love can fade, people might simply grow apart because it’s the nature of the beast, not because of warring parents or glowering villains. However, grounded situations can still have ethereal music and lyrics – see Gulzar’s Aandhi (“Tere bina zindagi”) or Ijaazat (“Mera kuch saamaan”).” And even in today’s indie cinema, so self-conscious about “cheesy” love songs, there is room for something as raw and heartbreaking as “Bahut Dukha Mann” from Mukkabaaz, which plays in the background as the boxer Shravan searches for his kidnapped wife, his “aatma” (soul).

I have special fondness, though, for the deliberately funny-sad song that moves from one meter to the next within seconds. Decades before Dev D’s “Emosanal Atyachaar” offered a hilariously rude commentary on our many angst-filled Devdases (“Bol bol, why did you ditch me / Zindagi bhi lele yaar, kill me / Bol bol, why did you ditch me / Whore”), there was “Na jaiyyo pardes” from Karma, in which two separated lovers express themselves in very different tones. First Poonam Dhillon plays it dead straight, reaching longingly towards the van carrying her beloved away; then Anil Kapoor yodels in the voice of Kishore Kumar, singing words like “O my darling don’t cry […] me going to die, oh bye bye”. To evoke a classical theory of aesthetic expression, these songs combine shoka rasa (sorrow) and haasya (merriment) in one package – and that’s as good a monument as you’ll find for the exhausting tragi-comedy of the romantic condition.

I have special fondness, though, for the deliberately funny-sad song that moves from one meter to the next within seconds. Decades before Dev D’s “Emosanal Atyachaar” offered a hilariously rude commentary on our many angst-filled Devdases (“Bol bol, why did you ditch me / Zindagi bhi lele yaar, kill me / Bol bol, why did you ditch me / Whore”), there was “Na jaiyyo pardes” from Karma, in which two separated lovers express themselves in very different tones. First Poonam Dhillon plays it dead straight, reaching longingly towards the van carrying her beloved away; then Anil Kapoor yodels in the voice of Kishore Kumar, singing words like “O my darling don’t cry […] me going to die, oh bye bye”. To evoke a classical theory of aesthetic expression, these songs combine shoka rasa (sorrow) and haasya (merriment) in one package – and that’s as good a monument as you’ll find for the exhausting tragi-comedy of the romantic condition. ------------------------------------

Here are videos of some of the songs mentioned here:

"O Saathi Re"

"Mera Kuch Saamaan"

"Beqas pe karam kijiye"

"Emosanal Atyachaar"

"Na Jaiyyo Pardes"

Published on February 15, 2018 08:19

February 13, 2018

An update to the Padmaavat post (after seeing the film)

When I wrote the original Padmaavat-related post, I hadn’t seen the film, and was called out for this during a longish Facebook discussion – the point I tried to make there was that I was putting down generalized thoughts about a certain form of criticism/reading, and that watching this specific film was not imperative to that end.

Well, I saw Bhansali’s film yesterday and liked it much more than I had expected to. One reason I had been putting off seeing it was that I don’t usually have the stamina these days for a nearly-three-hour movie-hall experience. Another was that SLB’s last, Bajirao Mastani, had left me largely bored and distracted. But this was a very different experience. While Padmaavat was patchy in places (I don’t know enough yet about what was censored or otherwise edited out) and began on a less-than-promising note with a computer-generated ostrich and a seemingly mummified Raza Murad, I was eventually drawn into its world, and thought the final 20-25 minutes ranked among the best work this much-maligned auteur has done.

This includes the things that come just before the Jauhar sequence: the brilliant Mirch Masala-like scene of the women hurling coal at Khilji, engaging in one of the last forms of violent resistance left to them; and before that, the Ratan Singh-Khilji swordfight. Wonderfully shot, performed and choreographed (Sham Kaushal’s work as stunt director merits that word), this scene combines some of the epic grandeur of similar scenes in non-Indian films like Troy with a quality that evoked war depiction in dance forms like kathakali. (The actors here are very much in character – Khilji a rude, swaggering force of nature, Ratan Singh prim and courtly in his movements – the way you don’t often expect actors to be in fight sequences. I was also reminded of some of the stylised action sequences from old Japanese films performed in the Noh tradition.)

Anyway: having watched the film, I now find it even harder to relate to Bhaskar’s article (which I was earlier looking at in abstract terms). Especially since the film did have a couple of scenes that made clear nods to contemporary gender-related discourse – such as the one where Padmaavati, addressing a woman who has accused her of bringing calamity on the kingdom, says words to the effect “You blame ME for drawing his attention, instead of blaming HIM for directing his unwanted attention at me?” Costume, setting and formal speech aside, this scene could easily have been from a socially conscious 2018 film about the victim-blaming culture. In any case, it made nonsense of my earlier thought-exercise about the possible inclusion of a supporting character who would provide an alternate, “progressive” perspective. This film didn’t need any such character.

Inevitably, some of the criticisms of my post have gone the route of “but you’re a man, you don’t have the right lenses to understand the problems with the film”. It is of course true that we all have lenses that derive from our life experiences, from our privilege and lack of privilege (which are things that are very complex and intersect and play off each other in dozens of ways – someone who is deeply privileged in one sense can be deeply unprivileged in another sense, and even within the same situation). But this is a very patronizing way of dismissing both my experience and the experiences of the women who share my views about this subject in general, and about this film in particular. The person I saw Padmaavat with (sensitive, intelligent and someone who has, like most women, experienced forms of sexual harassment or discrimination herself and even written about them) was even more moved by the film and its climax than I was. And she didn’t see any “glorification” or “misogyny” in that final passage.

It’s unfortunate that I even feel the need to say something so defensive-sounding or so obvious — but that’s what some of the discourse around reactions to Padmaavat (and ideology-blinkered criticism more generally) has come down to. And again, I’m not saying this to weigh the argument in my favour or to suggest that my view of the film is the “right” one or the “only possible reading” — just to reiterate that this isn’t anywhere near as simple as Men Feel This, Women Feel That.

[And now I should get back to the much less respectful piece I was writing, about the decapitated-but-still-fighting Rajput soldier as a version of the heroic male praying mantis, who continues servicing his woman after she has ripped off his head mid-coitus and eaten it]

Well, I saw Bhansali’s film yesterday and liked it much more than I had expected to. One reason I had been putting off seeing it was that I don’t usually have the stamina these days for a nearly-three-hour movie-hall experience. Another was that SLB’s last, Bajirao Mastani, had left me largely bored and distracted. But this was a very different experience. While Padmaavat was patchy in places (I don’t know enough yet about what was censored or otherwise edited out) and began on a less-than-promising note with a computer-generated ostrich and a seemingly mummified Raza Murad, I was eventually drawn into its world, and thought the final 20-25 minutes ranked among the best work this much-maligned auteur has done.

This includes the things that come just before the Jauhar sequence: the brilliant Mirch Masala-like scene of the women hurling coal at Khilji, engaging in one of the last forms of violent resistance left to them; and before that, the Ratan Singh-Khilji swordfight. Wonderfully shot, performed and choreographed (Sham Kaushal’s work as stunt director merits that word), this scene combines some of the epic grandeur of similar scenes in non-Indian films like Troy with a quality that evoked war depiction in dance forms like kathakali. (The actors here are very much in character – Khilji a rude, swaggering force of nature, Ratan Singh prim and courtly in his movements – the way you don’t often expect actors to be in fight sequences. I was also reminded of some of the stylised action sequences from old Japanese films performed in the Noh tradition.)

Anyway: having watched the film, I now find it even harder to relate to Bhaskar’s article (which I was earlier looking at in abstract terms). Especially since the film did have a couple of scenes that made clear nods to contemporary gender-related discourse – such as the one where Padmaavati, addressing a woman who has accused her of bringing calamity on the kingdom, says words to the effect “You blame ME for drawing his attention, instead of blaming HIM for directing his unwanted attention at me?” Costume, setting and formal speech aside, this scene could easily have been from a socially conscious 2018 film about the victim-blaming culture. In any case, it made nonsense of my earlier thought-exercise about the possible inclusion of a supporting character who would provide an alternate, “progressive” perspective. This film didn’t need any such character.

Inevitably, some of the criticisms of my post have gone the route of “but you’re a man, you don’t have the right lenses to understand the problems with the film”. It is of course true that we all have lenses that derive from our life experiences, from our privilege and lack of privilege (which are things that are very complex and intersect and play off each other in dozens of ways – someone who is deeply privileged in one sense can be deeply unprivileged in another sense, and even within the same situation). But this is a very patronizing way of dismissing both my experience and the experiences of the women who share my views about this subject in general, and about this film in particular. The person I saw Padmaavat with (sensitive, intelligent and someone who has, like most women, experienced forms of sexual harassment or discrimination herself and even written about them) was even more moved by the film and its climax than I was. And she didn’t see any “glorification” or “misogyny” in that final passage.

It’s unfortunate that I even feel the need to say something so defensive-sounding or so obvious — but that’s what some of the discourse around reactions to Padmaavat (and ideology-blinkered criticism more generally) has come down to. And again, I’m not saying this to weigh the argument in my favour or to suggest that my view of the film is the “right” one or the “only possible reading” — just to reiterate that this isn’t anywhere near as simple as Men Feel This, Women Feel That.

[And now I should get back to the much less respectful piece I was writing, about the decapitated-but-still-fighting Rajput soldier as a version of the heroic male praying mantis, who continues servicing his woman after she has ripped off his head mid-coitus and eaten it]

Published on February 13, 2018 20:32

February 10, 2018

Scattered thoughts on narrative context, ideology-oriented criticism and the Padmaavat discussion

[Note: this rambling post isn’t “about Padmaavat” as such – not having seen it yet, I can’t say anything specific about the film – but it derives from some of the conversations around it, especially the recent Swara Bhaskar piece “At the end of your magnum opus, I felt reduced to a vagina – only”, which you’ll find here]

-------------------------

At writing classes where I talk about film and literary criticism, narrative context gets discussed a lot, and a stimulating conversation along these lines began at the Sri Aurobindo Centre for Arts and Communication last week when, just as I was wondering if I should mention Padmaavat, the students did it for me.

These were intelligent, introspective students who came across as being liberal and engaged with social issues, but also had some reservations about Swara Bhaskar’s recent article. Both at the big-picture level of “why impose our contemporary moral codes and ideas about individual freedom on historical figures?” and at smaller, more specific levels. For instance, one of them said it was problematic to paint the film as being exclusively about women being sacrificed at the altar of patriarchal “honour”: Rajput men also went out and died for what they saw as a just cause; there was a common code of conduct in the face of invasion by someone who was considered the enemy. Another noted that Bhaskar had conflated Sati with Jauhar when they are different things involving different levels of agency and coercion.

My take: I liked some things about Bhaskar’s piece. It was thoughtful, made its points firmly and passionately, but without adopting the “this is so offensive, it mustn’t exist” stance that we routinely get from people who want to silence things that make them uncomfortable. (I stress this because I’m sure there are plenty of gloating social-media reactions that try to make a false equivalence between critical pieces like this one and the bullying diktats and threats issued by the Karni Sena etc.) Also, it’s refreshing when someone within the film industry is willing to express views that may raise the fraternity’s hackles.

Like the SACAC students, though, I had a couple of issues. Some thoughts:

-- Film being a powerful, seductive medium, it’s understandable – as someone living in a world that seems to be regressing in many ways, and where the likes of Donald Trump and the RSS hold positions of power – to feel discomfited by the knowledge that a filmmaker with Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s reach and his very particular artistic sensibilities has spent hundreds of crores on a huge, glamorous film about a woman celebrated for committing Jauhar (and played by a very popular star). Here is a director whose images and use of music can be so overwhelming that, irrespective of context, it can sometimes feel like his cinema is endorsing or celebrating whatever it depicts. To a degree, I get the exasperation of those who say “At this point in our cultural discourse about gender inequality and sexual harassment – when we are in the MeToo/Weinstein/post-Nirbhaya moment – HE had to make a film about THIS?”

Jauhar (and played by a very popular star). Here is a director whose images and use of music can be so overwhelming that, irrespective of context, it can sometimes feel like his cinema is endorsing or celebrating whatever it depicts. To a degree, I get the exasperation of those who say “At this point in our cultural discourse about gender inequality and sexual harassment – when we are in the MeToo/Weinstein/post-Nirbhaya moment – HE had to make a film about THIS?”

But once the choice of subject has been made, creative freedom exercised, what then? As a professional critic, or as a reasonably analytical viewer grappling with the film, is it okay to employ the progressive-ideology lens to the exclusion of all else (and in some cases, even at the expense of clear-sighted criticism)?

Bhaskar says: