Jai Arjun Singh's Blog, page 42

November 29, 2017

Tu Hai Mera Sunday, and the quiet charms of the not-quite narrative

[did this for Mint Lounge]

----------------

“What is this life, if full of care / we have no time to stand and stare,” a little girl lisps in a scene in Milind Dhaimade’s charming, low-key Tu Hai Mera Sunday . The WH Davies lines are part of a school assignment, but they have a wider relevance in this film about a group of friends who treasure their Sunday football games.

Cross-cutting between many stories, Tu Hai Mera Sunday examines the importance of being a slacker once in a while. The striking image we see in the first frame – a landscape of dusty old bikes piled up in a dump – could be a stand-in for the characters’ lives, which badly need to be un-cluttered: this could mean taking a break from the cut-throat corporate world to prevent yourself from having a status-anxiety-induced breakdown in public, or just finding a quiet space in a mad metropolis. (“Mumbai mein koi na koi jagah toh hogi na, jahaan mil ke kuch na kare. There must be somewhere in Bombay where we can hang around doing nothing.”) Even if that space is on the roof of a skyscraper, where Kavya (Shahana Goswami) goes to feel like the city, its crowds and noise are faraway things. (One might think of her as a distant cousin of the Rajkummar Rao character in Trapped , finding both a prison and a form of release many storeys above ground level.)

As if to give its stressed characters a breather, Dhaimade’s film is in no hurry to move its plot forward. It is mainly interested in watching a bunch of people dealing (or not dealing) with their problems. Or just having conversations that may not be about anything specific. But even at its most laidback, this isn’t what you’d call a non-narrative or anti-narrative film: those terms are best reserved for experimental or avant-garde works by directors like Terence Mallick or Mani Kaul. “Not very interested in narrative” may be a better descriptor, and there are many types of films in that sub-category too.

As if to give its stressed characters a breather, Dhaimade’s film is in no hurry to move its plot forward. It is mainly interested in watching a bunch of people dealing (or not dealing) with their problems. Or just having conversations that may not be about anything specific. But even at its most laidback, this isn’t what you’d call a non-narrative or anti-narrative film: those terms are best reserved for experimental or avant-garde works by directors like Terence Mallick or Mani Kaul. “Not very interested in narrative” may be a better descriptor, and there are many types of films in that sub-category too.

For instance, some stories get their tone from a passive protagonist – a person who is frozen in a state of inaction, because of circumstance or a character quirk, or both. The books of Kazuo Ishiguro, who just won the Nobel Prize, are full of such people, and the films adapted from them – notably the 1993 Remains of the Day, about an emotionally repressed butler – suggest turbulence buried under a placid, seemingly uneventful surface. Another of my favourite films in this vein, Saeed Mirza’s 1978 debut Arvind Desai ki Ajeeb Dastaan , is about a rich young man who wants to empathize with the unprivileged, but has no idea how to step out of the bubble he was born in; here is a truly limp-wristed “hero”, even though Dilip Dhawan, who played the part, could be as dashing as any of our mainstream leading men of the time.

Then there are works that refuse to provide a dramatic resolution or payoff, even when a definite narrative arc is involved. I was thinking of this while watching the new Netflix show Mindhunter , about an FBI unit’s efforts in the 1970s to understand the psychological makeup of serial killers. Part of the point of this series – co-produced by David Fincher, who also directed four episodes – is that there may not be any clear patterns or explanations when it comes to the sociopathic mind. Accordingly, even as it follows the broad format of a police procedural, Mindhunter is a work of ellipses and quiet fadeouts rather than full stops or exclamation marks – and this is made most obvious in its use of brief, ambiguous interludes about an anonymous man doing mundane things in Kansas. (Any true-crime aficionado will realise that this character is Dennis Rader, the notorious “BTK” killer who operated between the 1970s and the early 1990s, but he is never clearly identified and has no connection with the main narrative.) This makes the show similar in effect to one of Fincher’s best feature films, Zodiac, which played out as an existential, no-solutions-here narrative even though its premise – detectives and journalists on a killer’s trail – was a dramatic one.

This makes the show similar in effect to one of Fincher’s best feature films, Zodiac, which played out as an existential, no-solutions-here narrative even though its premise – detectives and journalists on a killer’s trail – was a dramatic one.

In recent Hindi cinema, examples of the “soak in the mood” film include the dreamlike Gurgaon – which is about a dysfunctional family becoming involved with crime, but has the texture of a story set underwater, where time moves at its own pace – and Mukti Bhawan, about an old man and his son making an appointment with Death in Benares, and then finding they will have to wait.

Like the above works, Tu Hai Mera Sunday prioritizes whimsy over exposition for most of its running time – but it becomes markedly more conventional, even conservative towards the end. In the last scene – set on that same skyscraper rooftop – Kavya and Arjun (Barun Sobti) express romantic feelings for each other, and then start talking about marriage, as if it were the inevitable (or the only possible) next step. It felt off-key to me that in a film about the importance of taking it easy and watching life go by, two urbane young people who have only known each other a few weeks, and haven’t even kissed yet, would so abruptly speak the language of proposals and engagement rings. But perhaps this is a reminder that cinema and life both naturally gravitate towards some sort of narrative; that it’s risky to be too unstructured or disorganized, and useful to have safety nets when you’re twenty storeys high.

[Related posts: Arvind Desai ki Ajeeb Dastaan; Gurgaon]

----------------

“What is this life, if full of care / we have no time to stand and stare,” a little girl lisps in a scene in Milind Dhaimade’s charming, low-key Tu Hai Mera Sunday . The WH Davies lines are part of a school assignment, but they have a wider relevance in this film about a group of friends who treasure their Sunday football games.

Cross-cutting between many stories, Tu Hai Mera Sunday examines the importance of being a slacker once in a while. The striking image we see in the first frame – a landscape of dusty old bikes piled up in a dump – could be a stand-in for the characters’ lives, which badly need to be un-cluttered: this could mean taking a break from the cut-throat corporate world to prevent yourself from having a status-anxiety-induced breakdown in public, or just finding a quiet space in a mad metropolis. (“Mumbai mein koi na koi jagah toh hogi na, jahaan mil ke kuch na kare. There must be somewhere in Bombay where we can hang around doing nothing.”) Even if that space is on the roof of a skyscraper, where Kavya (Shahana Goswami) goes to feel like the city, its crowds and noise are faraway things. (One might think of her as a distant cousin of the Rajkummar Rao character in Trapped , finding both a prison and a form of release many storeys above ground level.)

As if to give its stressed characters a breather, Dhaimade’s film is in no hurry to move its plot forward. It is mainly interested in watching a bunch of people dealing (or not dealing) with their problems. Or just having conversations that may not be about anything specific. But even at its most laidback, this isn’t what you’d call a non-narrative or anti-narrative film: those terms are best reserved for experimental or avant-garde works by directors like Terence Mallick or Mani Kaul. “Not very interested in narrative” may be a better descriptor, and there are many types of films in that sub-category too.

As if to give its stressed characters a breather, Dhaimade’s film is in no hurry to move its plot forward. It is mainly interested in watching a bunch of people dealing (or not dealing) with their problems. Or just having conversations that may not be about anything specific. But even at its most laidback, this isn’t what you’d call a non-narrative or anti-narrative film: those terms are best reserved for experimental or avant-garde works by directors like Terence Mallick or Mani Kaul. “Not very interested in narrative” may be a better descriptor, and there are many types of films in that sub-category too. For instance, some stories get their tone from a passive protagonist – a person who is frozen in a state of inaction, because of circumstance or a character quirk, or both. The books of Kazuo Ishiguro, who just won the Nobel Prize, are full of such people, and the films adapted from them – notably the 1993 Remains of the Day, about an emotionally repressed butler – suggest turbulence buried under a placid, seemingly uneventful surface. Another of my favourite films in this vein, Saeed Mirza’s 1978 debut Arvind Desai ki Ajeeb Dastaan , is about a rich young man who wants to empathize with the unprivileged, but has no idea how to step out of the bubble he was born in; here is a truly limp-wristed “hero”, even though Dilip Dhawan, who played the part, could be as dashing as any of our mainstream leading men of the time.

Then there are works that refuse to provide a dramatic resolution or payoff, even when a definite narrative arc is involved. I was thinking of this while watching the new Netflix show Mindhunter , about an FBI unit’s efforts in the 1970s to understand the psychological makeup of serial killers. Part of the point of this series – co-produced by David Fincher, who also directed four episodes – is that there may not be any clear patterns or explanations when it comes to the sociopathic mind. Accordingly, even as it follows the broad format of a police procedural, Mindhunter is a work of ellipses and quiet fadeouts rather than full stops or exclamation marks – and this is made most obvious in its use of brief, ambiguous interludes about an anonymous man doing mundane things in Kansas. (Any true-crime aficionado will realise that this character is Dennis Rader, the notorious “BTK” killer who operated between the 1970s and the early 1990s, but he is never clearly identified and has no connection with the main narrative.)

This makes the show similar in effect to one of Fincher’s best feature films, Zodiac, which played out as an existential, no-solutions-here narrative even though its premise – detectives and journalists on a killer’s trail – was a dramatic one.

This makes the show similar in effect to one of Fincher’s best feature films, Zodiac, which played out as an existential, no-solutions-here narrative even though its premise – detectives and journalists on a killer’s trail – was a dramatic one.In recent Hindi cinema, examples of the “soak in the mood” film include the dreamlike Gurgaon – which is about a dysfunctional family becoming involved with crime, but has the texture of a story set underwater, where time moves at its own pace – and Mukti Bhawan, about an old man and his son making an appointment with Death in Benares, and then finding they will have to wait.

Like the above works, Tu Hai Mera Sunday prioritizes whimsy over exposition for most of its running time – but it becomes markedly more conventional, even conservative towards the end. In the last scene – set on that same skyscraper rooftop – Kavya and Arjun (Barun Sobti) express romantic feelings for each other, and then start talking about marriage, as if it were the inevitable (or the only possible) next step. It felt off-key to me that in a film about the importance of taking it easy and watching life go by, two urbane young people who have only known each other a few weeks, and haven’t even kissed yet, would so abruptly speak the language of proposals and engagement rings. But perhaps this is a reminder that cinema and life both naturally gravitate towards some sort of narrative; that it’s risky to be too unstructured or disorganized, and useful to have safety nets when you’re twenty storeys high.

[Related posts: Arvind Desai ki Ajeeb Dastaan; Gurgaon]

Published on November 29, 2017 05:14

November 20, 2017

In which Sherlock Holmes meets Jack the Ripper

[the third entry in my series about crime fiction for Scroll. Earlier pieces here and here]

--------------------------------------------

“A fictional super-detective and a notorious real-life serial killer walk into a bar together…”

I don’t know if crime buffs have yet thought up a joke that begins with that line, but this gin joint would likely be in London’s poverty-drenched East End in the 1880s: the sort of place where shady characters might drop in for a peg or pint at any time, even 7 AM, to ward off the cold and other miseries. And the carousing sleuth and murderer would be Sherlock Holmes and Jack the Ripper respectively.

These two men have often faced off in the pages of novels and short stories – and, apparently, in video games too. It’s a fascinating pairing for obvious reasons. They operated on opposite sides of the law in the same metropolis at the same time: Arthur Conan Doyle’s first Holmes story appeared in 1887, while the canonical Ripper murders took place in the summer and autumn of 1888.

And if you think the gap between fiction and fact creates a credibility problem, consider this paradox: Holmes, the imagined character, has been such a recognizable, well-loved and widely portrayed figure over the past century that many people think he was an actual person; while the Ripper, who really did exist, has become shadowy, mythical – and sometimes even romanticized – because he was never caught. (A dozen or more authors have written books naming their candidate and pompously declaring “case closed” – the trouble is that they have confidently identified a dozen different people.) So much so that the story has been mined even in science-fiction and fantasy, as in the Star Trek episode “Wolf in the Fold”, which identifies Red Jack as an evil energy force that shifts form over the centuries.

There is no point trying to list all the Sherlock Holmes-vs-Jack the Ripper fiction out there, but the more readable efforts include the novella A Study in Terror, notable for its narrative within a narrative: in the 1960s, ace detective Ellery Queen comes across an old document detailing Holmes’s efforts to solve the London murders; while he reads, Ellery conducts a parallel investigation of his own, eventually figuring that Holmes may have been deliberately elusive about the killer’s identity. In other words, here are two celebrated fictional sleuths tangling with a real-life mystery, and with each other, across time and space.

There is also the very enjoyable 1979 film Murder by Decree, notable less for its plot (which draws on a much-rehashed conspiracy theory involving a Royal Family scandal) and more for its atmospheric set design and its cast -- Christopher Plummer and James Mason had a grand time playing Holmes and Watson respectively, and the supporting players included such heavyweights as John Gielgud, Genevieve Bujold and Donald Sutherland.

There is also the very enjoyable 1979 film Murder by Decree, notable less for its plot (which draws on a much-rehashed conspiracy theory involving a Royal Family scandal) and more for its atmospheric set design and its cast -- Christopher Plummer and James Mason had a grand time playing Holmes and Watson respectively, and the supporting players included such heavyweights as John Gielgud, Genevieve Bujold and Donald Sutherland.

For me, though, Lyndsay Faye’s 2009 novel Dust and Shadow: An Account of the Ripper Killings by Dr John H Watson has a very special place in this sub-sub-category of crime writing. This skilled debut manages to be that rare thing, a book that should please both Sherlock Holmes buffs (including the ones who have mixed feelings about other authors stomping on Conan Doyle’s terrain) and Jack the Ripper scholars who like their Ripper-based fiction to be rooted in the facts of the case (even if the “solution” offered is far-fetched).

*****

Dust and Shadow is, of course, told in Dr Watson’s voice, deliberately prim by modern standards – Faye does a fine job of imitating the style of the original stories – but also warm and admiring when he speaks of his brilliant friend, and appropriately repulsed when he sees the bodies left by the unknown killer. The narrative begins with a short prelude set in Herefordshire in 1887 – this makes for a nice Sherlock Holmes mini-adventure in itself, but also serves a purpose that the reader will only learn near the book’s end – and then moves to the summer of the next year. A series of murders and mutilations terrify Whitechapel. Holmes, naturally, becomes involved.

Perhaps more involved than even he would like to be.

One of the recurring themes in modern serial-killer fiction – such as Thomas Harris’s Red Dragon – is the idea that a psychopath and the detective who pursues him are two sides of the same coin: both geniuses, both deeply disturbed people, one of whom has transformed his darkest impulses from thought into action, while the other is always walking a fine line. “The reason you caught me,” Hannibal Lecter tells Will Graham in Red Dragon, “is because we are just alike.” Three decades later, the gorgeous-looking TV show Hannibal explored this thought over three seasons.

Faye subtly uses the idea in her novel, without underlining it or indulging in any anachronisms that would take us out of the world of 1880s England (a time when little if anything was known about serial killers and their psychological makeup). Reading Dust and Shadow, it made complete sense to me that if Sherlock Holmes had existed and become involved with the Ripper investigation – prowling Whitechapel’s alleys in disguise at odd hours, frequenting opium dens, employing esoteric methods to conduct an unofficial investigation – someone or the other might suspect HIM of being the murderer.

Faye subtly uses the idea in her novel, without underlining it or indulging in any anachronisms that would take us out of the world of 1880s England (a time when little if anything was known about serial killers and their psychological makeup). Reading Dust and Shadow, it made complete sense to me that if Sherlock Holmes had existed and become involved with the Ripper investigation – prowling Whitechapel’s alleys in disguise at odd hours, frequenting opium dens, employing esoteric methods to conduct an unofficial investigation – someone or the other might suspect HIM of being the murderer.

This is what happens here. Shortly after an encounter with the Ripper that leaves him injured, Holmes finds that an unscrupulous journalist is writing articles damning him. And that the killer might be setting out to implicate him too. This puts our super-sleuth in a race to not just solve the case, and heal his hurt ego, but also to clear his name – and what we see in the process is a vulnerable Holmes and a paternal, protective Watson who takes it upon himself to be more than just a silent admirer and chronicler.

Conan Doyle’s other fictional characters – including Inspector Lestrade and Mrs Hudson – are part of this story, as are the comforting bachelor’s quarters in 221B Baker Street, but so are real-life people from the period, such as George Lusk, head of a Vigilance Committee during the killings, and the much-disliked police commissioner Sir Charles Warren. The book’s third “hero” – a young woman named Mary Ann Monk, who collects valuable information for Holmes in the East End – was an actual (if very peripheral) figure in the Ripper investigation, but is fleshed out into a spirited and resourceful character here.

Apart from its storytelling merits, this book can serve as a lesson to many historical-fiction authors in how background detail and attention to language can bring internal logic and credibility even to a fantasy narrative. When Holmes goes undercover in Whitechapel, we have no trouble believing that someone with his powers of observation would soon be able to acquaint himself with every foul nook and dark cranny of the impossibly maze-like East End of the 1880s – a place that in real life confounded the efforts of a large police force and helped the anonymous murderer get away with his crimes.

A tour de force passage in this respect occurs near the end when Holmes interrogates a disoriented and scared witness who followed the Ripper to his house but has no idea exactly which labyrinthine part of Whitechapel he was stumbling through. By asking a series of questions, asking the witness to remember landmarks, the width of this or that lane, the nature of the traffic on it, and so on, Holmes unerringly arrives at almost the exact address. Riveting though this passage is on its own terms for a lover of detective stories (or Sherlock Holmes’s methods), it becomes even more so when you study the actual geography of the period (Faye provides a map too) and realise that there is nothing fictional about the details of the route being discussed.

****

Dust and Shadow did two things for me. First, speaking as a longtime amateur Ripperologist who has been fascinated not only by the case but also by the huge range of reactions it has spawned over the decades, it works as a good Jack the Ripper story, shorn of the sensationalism and the factual errors that have littered even many non-fiction books. I think authors like Philip Sugden and Donald Rumbelow – among the most scrupulous Ripper scholars – would have approved of it. (Incidentally I first came across Faye’s writing via her plaintive and unsettling short story “The Sparrow and the Lark”, told in the voice of Mary Jane Kelly, the last of Jack the Ripper’s victims. You’ll find that story – along with “A Study in Terror” and many other worthies – in Otto Penzler’s anthology Jack the Ripper: Fact, Fiction, Legend.)

Second, as someone whose reading of Conan Doyle’s original Holmes tales has been less than comprehensive (I devoured many of them at one go as a young teen, and somehow never revisited them), this book stoked a desire to rediscover some of those stories, particularly the longer ones. Not just to return to the world of Dr Watson and his moody flat-mate, but also to see – and this will sound blasphemous to Holmes purists – how the originals compare with Faye’s terrific reimagining.

-----------------------

[Related post: this column about true-crime books; and an illustration from hell]

--------------------------------------------

“A fictional super-detective and a notorious real-life serial killer walk into a bar together…”

I don’t know if crime buffs have yet thought up a joke that begins with that line, but this gin joint would likely be in London’s poverty-drenched East End in the 1880s: the sort of place where shady characters might drop in for a peg or pint at any time, even 7 AM, to ward off the cold and other miseries. And the carousing sleuth and murderer would be Sherlock Holmes and Jack the Ripper respectively.

These two men have often faced off in the pages of novels and short stories – and, apparently, in video games too. It’s a fascinating pairing for obvious reasons. They operated on opposite sides of the law in the same metropolis at the same time: Arthur Conan Doyle’s first Holmes story appeared in 1887, while the canonical Ripper murders took place in the summer and autumn of 1888.

And if you think the gap between fiction and fact creates a credibility problem, consider this paradox: Holmes, the imagined character, has been such a recognizable, well-loved and widely portrayed figure over the past century that many people think he was an actual person; while the Ripper, who really did exist, has become shadowy, mythical – and sometimes even romanticized – because he was never caught. (A dozen or more authors have written books naming their candidate and pompously declaring “case closed” – the trouble is that they have confidently identified a dozen different people.) So much so that the story has been mined even in science-fiction and fantasy, as in the Star Trek episode “Wolf in the Fold”, which identifies Red Jack as an evil energy force that shifts form over the centuries.

There is no point trying to list all the Sherlock Holmes-vs-Jack the Ripper fiction out there, but the more readable efforts include the novella A Study in Terror, notable for its narrative within a narrative: in the 1960s, ace detective Ellery Queen comes across an old document detailing Holmes’s efforts to solve the London murders; while he reads, Ellery conducts a parallel investigation of his own, eventually figuring that Holmes may have been deliberately elusive about the killer’s identity. In other words, here are two celebrated fictional sleuths tangling with a real-life mystery, and with each other, across time and space.

There is also the very enjoyable 1979 film Murder by Decree, notable less for its plot (which draws on a much-rehashed conspiracy theory involving a Royal Family scandal) and more for its atmospheric set design and its cast -- Christopher Plummer and James Mason had a grand time playing Holmes and Watson respectively, and the supporting players included such heavyweights as John Gielgud, Genevieve Bujold and Donald Sutherland.

There is also the very enjoyable 1979 film Murder by Decree, notable less for its plot (which draws on a much-rehashed conspiracy theory involving a Royal Family scandal) and more for its atmospheric set design and its cast -- Christopher Plummer and James Mason had a grand time playing Holmes and Watson respectively, and the supporting players included such heavyweights as John Gielgud, Genevieve Bujold and Donald Sutherland.For me, though, Lyndsay Faye’s 2009 novel Dust and Shadow: An Account of the Ripper Killings by Dr John H Watson has a very special place in this sub-sub-category of crime writing. This skilled debut manages to be that rare thing, a book that should please both Sherlock Holmes buffs (including the ones who have mixed feelings about other authors stomping on Conan Doyle’s terrain) and Jack the Ripper scholars who like their Ripper-based fiction to be rooted in the facts of the case (even if the “solution” offered is far-fetched).

*****

Dust and Shadow is, of course, told in Dr Watson’s voice, deliberately prim by modern standards – Faye does a fine job of imitating the style of the original stories – but also warm and admiring when he speaks of his brilliant friend, and appropriately repulsed when he sees the bodies left by the unknown killer. The narrative begins with a short prelude set in Herefordshire in 1887 – this makes for a nice Sherlock Holmes mini-adventure in itself, but also serves a purpose that the reader will only learn near the book’s end – and then moves to the summer of the next year. A series of murders and mutilations terrify Whitechapel. Holmes, naturally, becomes involved.

Perhaps more involved than even he would like to be.

One of the recurring themes in modern serial-killer fiction – such as Thomas Harris’s Red Dragon – is the idea that a psychopath and the detective who pursues him are two sides of the same coin: both geniuses, both deeply disturbed people, one of whom has transformed his darkest impulses from thought into action, while the other is always walking a fine line. “The reason you caught me,” Hannibal Lecter tells Will Graham in Red Dragon, “is because we are just alike.” Three decades later, the gorgeous-looking TV show Hannibal explored this thought over three seasons.

Faye subtly uses the idea in her novel, without underlining it or indulging in any anachronisms that would take us out of the world of 1880s England (a time when little if anything was known about serial killers and their psychological makeup). Reading Dust and Shadow, it made complete sense to me that if Sherlock Holmes had existed and become involved with the Ripper investigation – prowling Whitechapel’s alleys in disguise at odd hours, frequenting opium dens, employing esoteric methods to conduct an unofficial investigation – someone or the other might suspect HIM of being the murderer.

Faye subtly uses the idea in her novel, without underlining it or indulging in any anachronisms that would take us out of the world of 1880s England (a time when little if anything was known about serial killers and their psychological makeup). Reading Dust and Shadow, it made complete sense to me that if Sherlock Holmes had existed and become involved with the Ripper investigation – prowling Whitechapel’s alleys in disguise at odd hours, frequenting opium dens, employing esoteric methods to conduct an unofficial investigation – someone or the other might suspect HIM of being the murderer. This is what happens here. Shortly after an encounter with the Ripper that leaves him injured, Holmes finds that an unscrupulous journalist is writing articles damning him. And that the killer might be setting out to implicate him too. This puts our super-sleuth in a race to not just solve the case, and heal his hurt ego, but also to clear his name – and what we see in the process is a vulnerable Holmes and a paternal, protective Watson who takes it upon himself to be more than just a silent admirer and chronicler.

Conan Doyle’s other fictional characters – including Inspector Lestrade and Mrs Hudson – are part of this story, as are the comforting bachelor’s quarters in 221B Baker Street, but so are real-life people from the period, such as George Lusk, head of a Vigilance Committee during the killings, and the much-disliked police commissioner Sir Charles Warren. The book’s third “hero” – a young woman named Mary Ann Monk, who collects valuable information for Holmes in the East End – was an actual (if very peripheral) figure in the Ripper investigation, but is fleshed out into a spirited and resourceful character here.

Apart from its storytelling merits, this book can serve as a lesson to many historical-fiction authors in how background detail and attention to language can bring internal logic and credibility even to a fantasy narrative. When Holmes goes undercover in Whitechapel, we have no trouble believing that someone with his powers of observation would soon be able to acquaint himself with every foul nook and dark cranny of the impossibly maze-like East End of the 1880s – a place that in real life confounded the efforts of a large police force and helped the anonymous murderer get away with his crimes.

A tour de force passage in this respect occurs near the end when Holmes interrogates a disoriented and scared witness who followed the Ripper to his house but has no idea exactly which labyrinthine part of Whitechapel he was stumbling through. By asking a series of questions, asking the witness to remember landmarks, the width of this or that lane, the nature of the traffic on it, and so on, Holmes unerringly arrives at almost the exact address. Riveting though this passage is on its own terms for a lover of detective stories (or Sherlock Holmes’s methods), it becomes even more so when you study the actual geography of the period (Faye provides a map too) and realise that there is nothing fictional about the details of the route being discussed.

****

Dust and Shadow did two things for me. First, speaking as a longtime amateur Ripperologist who has been fascinated not only by the case but also by the huge range of reactions it has spawned over the decades, it works as a good Jack the Ripper story, shorn of the sensationalism and the factual errors that have littered even many non-fiction books. I think authors like Philip Sugden and Donald Rumbelow – among the most scrupulous Ripper scholars – would have approved of it. (Incidentally I first came across Faye’s writing via her plaintive and unsettling short story “The Sparrow and the Lark”, told in the voice of Mary Jane Kelly, the last of Jack the Ripper’s victims. You’ll find that story – along with “A Study in Terror” and many other worthies – in Otto Penzler’s anthology Jack the Ripper: Fact, Fiction, Legend.)

Second, as someone whose reading of Conan Doyle’s original Holmes tales has been less than comprehensive (I devoured many of them at one go as a young teen, and somehow never revisited them), this book stoked a desire to rediscover some of those stories, particularly the longer ones. Not just to return to the world of Dr Watson and his moody flat-mate, but also to see – and this will sound blasphemous to Holmes purists – how the originals compare with Faye’s terrific reimagining.

-----------------------

[Related post: this column about true-crime books; and an illustration from hell]

Published on November 20, 2017 22:39

November 17, 2017

Actorly pairings – expected ones and unusual ones

[Did this for Mint Lounge]

-----------------

Watching Saket Chaudhary’s Hindi Medium a few weeks ago, I found myself momentarily whisked away to another filmic universe. This happened when Irrfan Khan, playing a father who is trying to get his daughter into a good English-medium school, and Tillotama Shome, in a supporting role as a disdainful counsellor, first appeared together on screen. I had a hard time concentrating on the scene because my mind went back to the last time I had seen these two actors share a frame – in a vastly different sort of film in which they played very different roles.

In Anup Singh’s mesmerizing 2013 film

Qissa: Tale of a Lonely Ghost

, set just after Partition, Irrfan is a Sikh patriarch who, without heeding any counsel or acknowledging his duplicity even to himself, pretends that his newborn daughter is a son; Shome (in a stunning performance) is this unfortunate in-between, her life as partitioned as the newly independent country she is living in.

In Anup Singh’s mesmerizing 2013 film

Qissa: Tale of a Lonely Ghost

, set just after Partition, Irrfan is a Sikh patriarch who, without heeding any counsel or acknowledging his duplicity even to himself, pretends that his newborn daughter is a son; Shome (in a stunning performance) is this unfortunate in-between, her life as partitioned as the newly independent country she is living in.

As a movie nerd who likes to connect dots, one might half-jokingly note that both these stories are about challenges facing parents. But the differences are much more pronounced. Qissa was a great big-theatre film, an intense widescreen experience that also, paradoxically, manages to feel claustrophobic. It is shot in dark, muted colours; even the daytime scenes have a stygian, oppressive feel to them. Hindi Medium, on the other hand, is bright and colourful, not least because of its depiction of the main family’s flashy, nouveau-riche lifestyle. It is an upbeat, fast-paced portrayal of modern life in a status-conscious world, while Singh’s film is a stately period work that finds exactly the right tone and pace to tell the story of a family frozen in time.

In comparing these two instances of co-stars in disparate films, I’m not trying to make a point about acting versatility (though Khan and Shome are both terrific performers, well capable of inhabiting a range of roles). It’s just that I was reminded of the effect our knowledge of an actor’s history can have on our viewing experience: how seeing the same performers in a variety of roles or situations can help one appreciate different filmmaking styles or sensibilities.

There are variations on this, of course. When watching a well-established screen pairing over a period of time, there might be a strong component of nostalgia involved. For example, we see Katharine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy together as classic Hollywood matinee idols performing a love-hate waltz in Woman of the Year (1942) – and then again as a long-married couple in Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner 25 years later (with Tracy, who died just after the film’s completion, looking haggard and older than he really was) – and we become aware not just that glamorous, larger-than-life stars are mortal, but of our own aging process and how it affects the way we experience films. Something similar happens when we see Farooque Shaikh and Deepti Naval as an elderly couple tentatively exploring romance in Listen…Amaya , with some prior knowledge of what these actors were like decades earlier in films like Chashme Baddoor and Saath Saath.

With cinema getting more self-referential by the year, there are also cases of contemporary directors wittily playing off or subverting our expectations of an old pairing. One of the most indelible images from the Middle Cinema of the 1970s was Amitabh Bachchan and Moushumi Chatterjee splashing through rain-drenched south Bombay in Manzil, while “Rim Jhim Gire Saawan” played on the soundtrack and KK Mahajan’s camera performed a dizzying dance around them – a marvelous portrayal of romantic love in a city that might swallow the lovers up at any moment. It’s likely that the director Shoojit Sircar and the writer Juhi Chaturvedi – both of whom were fans of the Middle Cinema – had those images in mind when they cast Chatterjee as Bachchan’s sister-in-law (with whom he is always bickering) in Piku, a film where the character name Bhaskor Banerjee was also a nod to Bachchan’s role in another major work of that decade, Anand.

With cinema getting more self-referential by the year, there are also cases of contemporary directors wittily playing off or subverting our expectations of an old pairing. One of the most indelible images from the Middle Cinema of the 1970s was Amitabh Bachchan and Moushumi Chatterjee splashing through rain-drenched south Bombay in Manzil, while “Rim Jhim Gire Saawan” played on the soundtrack and KK Mahajan’s camera performed a dizzying dance around them – a marvelous portrayal of romantic love in a city that might swallow the lovers up at any moment. It’s likely that the director Shoojit Sircar and the writer Juhi Chaturvedi – both of whom were fans of the Middle Cinema – had those images in mind when they cast Chatterjee as Bachchan’s sister-in-law (with whom he is always bickering) in Piku, a film where the character name Bhaskor Banerjee was also a nod to Bachchan’s role in another major work of that decade, Anand.

At other times, the same director may use two actors in subtly similar ways in different situations. Most film enthusiasts know Akira Kurosawa’s medieval-era epic The Seven Samurai, in which the veteran Takashi Shimura plays the wise, grizzled, somewhat weary leader of the samurai while the younger Toshiro Mifune is the snarling upstart who wants to become a part of the group (and must be kept in check by the older man). But many years before that, in a film set in contemporary Japan – Drunken Angel – Kurosawa had already begun the process of creating a mould for the two actors: Shimura was a jaded doctor who serves as a mentor and guiding light for Mifune’s brash young gangster.

must be kept in check by the older man). But many years before that, in a film set in contemporary Japan – Drunken Angel – Kurosawa had already begun the process of creating a mould for the two actors: Shimura was a jaded doctor who serves as a mentor and guiding light for Mifune’s brash young gangster.

To watch these two films next to each other is to see how a director might show versatility in one sense (that is, making movies with different subject matter and settings) while also achieving an authorial consistency in another respect – through the carefully worked out use of screen personalities whom a viewer can recognize, relate to and incorporate into their experience of a film.

--------------------------------------

[Related posts: Qissa, Listen... Amaya, Familiarity breeds affection]

-----------------

Watching Saket Chaudhary’s Hindi Medium a few weeks ago, I found myself momentarily whisked away to another filmic universe. This happened when Irrfan Khan, playing a father who is trying to get his daughter into a good English-medium school, and Tillotama Shome, in a supporting role as a disdainful counsellor, first appeared together on screen. I had a hard time concentrating on the scene because my mind went back to the last time I had seen these two actors share a frame – in a vastly different sort of film in which they played very different roles.

In Anup Singh’s mesmerizing 2013 film

Qissa: Tale of a Lonely Ghost

, set just after Partition, Irrfan is a Sikh patriarch who, without heeding any counsel or acknowledging his duplicity even to himself, pretends that his newborn daughter is a son; Shome (in a stunning performance) is this unfortunate in-between, her life as partitioned as the newly independent country she is living in.

In Anup Singh’s mesmerizing 2013 film

Qissa: Tale of a Lonely Ghost

, set just after Partition, Irrfan is a Sikh patriarch who, without heeding any counsel or acknowledging his duplicity even to himself, pretends that his newborn daughter is a son; Shome (in a stunning performance) is this unfortunate in-between, her life as partitioned as the newly independent country she is living in. As a movie nerd who likes to connect dots, one might half-jokingly note that both these stories are about challenges facing parents. But the differences are much more pronounced. Qissa was a great big-theatre film, an intense widescreen experience that also, paradoxically, manages to feel claustrophobic. It is shot in dark, muted colours; even the daytime scenes have a stygian, oppressive feel to them. Hindi Medium, on the other hand, is bright and colourful, not least because of its depiction of the main family’s flashy, nouveau-riche lifestyle. It is an upbeat, fast-paced portrayal of modern life in a status-conscious world, while Singh’s film is a stately period work that finds exactly the right tone and pace to tell the story of a family frozen in time.

In comparing these two instances of co-stars in disparate films, I’m not trying to make a point about acting versatility (though Khan and Shome are both terrific performers, well capable of inhabiting a range of roles). It’s just that I was reminded of the effect our knowledge of an actor’s history can have on our viewing experience: how seeing the same performers in a variety of roles or situations can help one appreciate different filmmaking styles or sensibilities.

There are variations on this, of course. When watching a well-established screen pairing over a period of time, there might be a strong component of nostalgia involved. For example, we see Katharine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy together as classic Hollywood matinee idols performing a love-hate waltz in Woman of the Year (1942) – and then again as a long-married couple in Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner 25 years later (with Tracy, who died just after the film’s completion, looking haggard and older than he really was) – and we become aware not just that glamorous, larger-than-life stars are mortal, but of our own aging process and how it affects the way we experience films. Something similar happens when we see Farooque Shaikh and Deepti Naval as an elderly couple tentatively exploring romance in Listen…Amaya , with some prior knowledge of what these actors were like decades earlier in films like Chashme Baddoor and Saath Saath.

With cinema getting more self-referential by the year, there are also cases of contemporary directors wittily playing off or subverting our expectations of an old pairing. One of the most indelible images from the Middle Cinema of the 1970s was Amitabh Bachchan and Moushumi Chatterjee splashing through rain-drenched south Bombay in Manzil, while “Rim Jhim Gire Saawan” played on the soundtrack and KK Mahajan’s camera performed a dizzying dance around them – a marvelous portrayal of romantic love in a city that might swallow the lovers up at any moment. It’s likely that the director Shoojit Sircar and the writer Juhi Chaturvedi – both of whom were fans of the Middle Cinema – had those images in mind when they cast Chatterjee as Bachchan’s sister-in-law (with whom he is always bickering) in Piku, a film where the character name Bhaskor Banerjee was also a nod to Bachchan’s role in another major work of that decade, Anand.

With cinema getting more self-referential by the year, there are also cases of contemporary directors wittily playing off or subverting our expectations of an old pairing. One of the most indelible images from the Middle Cinema of the 1970s was Amitabh Bachchan and Moushumi Chatterjee splashing through rain-drenched south Bombay in Manzil, while “Rim Jhim Gire Saawan” played on the soundtrack and KK Mahajan’s camera performed a dizzying dance around them – a marvelous portrayal of romantic love in a city that might swallow the lovers up at any moment. It’s likely that the director Shoojit Sircar and the writer Juhi Chaturvedi – both of whom were fans of the Middle Cinema – had those images in mind when they cast Chatterjee as Bachchan’s sister-in-law (with whom he is always bickering) in Piku, a film where the character name Bhaskor Banerjee was also a nod to Bachchan’s role in another major work of that decade, Anand. At other times, the same director may use two actors in subtly similar ways in different situations. Most film enthusiasts know Akira Kurosawa’s medieval-era epic The Seven Samurai, in which the veteran Takashi Shimura plays the wise, grizzled, somewhat weary leader of the samurai while the younger Toshiro Mifune is the snarling upstart who wants to become a part of the group (and

must be kept in check by the older man). But many years before that, in a film set in contemporary Japan – Drunken Angel – Kurosawa had already begun the process of creating a mould for the two actors: Shimura was a jaded doctor who serves as a mentor and guiding light for Mifune’s brash young gangster.

must be kept in check by the older man). But many years before that, in a film set in contemporary Japan – Drunken Angel – Kurosawa had already begun the process of creating a mould for the two actors: Shimura was a jaded doctor who serves as a mentor and guiding light for Mifune’s brash young gangster. To watch these two films next to each other is to see how a director might show versatility in one sense (that is, making movies with different subject matter and settings) while also achieving an authorial consistency in another respect – through the carefully worked out use of screen personalities whom a viewer can recognize, relate to and incorporate into their experience of a film.

--------------------------------------

[Related posts: Qissa, Listen... Amaya, Familiarity breeds affection]

Published on November 17, 2017 22:13

November 3, 2017

On How to Travel Light, a memoir about being bipolar

[Did this short review of Shreevatsa Nevatia’s new book, for Open magazine. As you can see, a review of a confessional book can become self-indulgently confessional itself. But I left out something very important too. Nevatia’s memoir made me think of my father, a delusional, paranoid, lonely man who died pathetically a few months ago, having spent years estranging himself from everyone who might ever have cared for him – and looked out for (as opposed to “looked after by”) in his last days by a son who discharged responsibilities without really caring about him; who was more scared about genetic legacies and inherited madness than anything else.

My father may have been an undiagnosed case of bipolarity - there definitely was a mental condition of some sort. And he wrote daily too. (A way of holding on to things, or convincing yourself that you’re sane?) There are still dozens of journals gathering dust in his house, and I can't look closely at them]

-----------------------

In my favourite chapter in

How to Travel Light

, Shreevatsa Nevatia’s memoir about his struggle with bipolarity, the author examines his relationship with films such as Apur Sansar and The Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. Discussing the scene in the former where the protagonist Apu stands in for a “mad groom” and marries a young girl he has never met before, Nevatia says that he sees two aspects of his own personality in these two men: Binu, delusional, clad in finery and destined to fall, and Apu, “scared and reluctant, but desirous of grandeur”.

In my favourite chapter in

How to Travel Light

, Shreevatsa Nevatia’s memoir about his struggle with bipolarity, the author examines his relationship with films such as Apur Sansar and The Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. Discussing the scene in the former where the protagonist Apu stands in for a “mad groom” and marries a young girl he has never met before, Nevatia says that he sees two aspects of his own personality in these two men: Binu, delusional, clad in finery and destined to fall, and Apu, “scared and reluctant, but desirous of grandeur”.

To me, this passage – and what follows in the chapter – reads like intense, very personal film criticism of the sort I have special fondness for as a writer and reader. And a suggestion rears its head: obsessively finding patterns, connecting dots that most other people can’t see, locating yourself in gestures and lines of dialogue – all this may be a form of mental illness too. (Reviewers, beware.)

Other readers of How to Travel Light will undoubtedly find resonances in other chapters. They will probably find many things to admire, and a few things to be bored by, for a book like this is – to some degree at least – an exercise in navel-scratching. However well-written or insightful, there are passages that can seem of interest mainly to the author and the circle of family and friends who witnessed his ups and downs over the years.

Many people – friends, lovers, doctors, fellow sufferers, parents, siblings – flit through these pages, and one of the tics of Nevatia’s writing is to simply bring someone into the narrative by naming him or her, but without immediately explaining who this is. Add to this the fragmented, non-linear narrative – covering his many stints in rehab clinics, being sexually abused as a child by a cousin who was ten years older, the diagnosis of his condition in 2007, his ongoing attempts to give up drugs – and one gets the sense of a life lived in a blur, alternating between periods of rapture and depression.

Amidst all that chaos, there are startlingly vivid descriptions: Nevatia likens his isolation (and possible delusions of omniscience) to the terrifying Puranic image of Vishnu alone on his snake in an endless ocean. (Later, a memory of his grandmother dressing him up as the child Krishna is echoed in another Apur Sansar scene.) He tries to understand how his condition has affected his relationships. He mulls the social-media circus and how its momentary highs can make anyone seem potentially bipolar. And he circles back to the idea that many people need some “madness” to be able to do their best work, that the mind needs turbulence to thrive. (But how narrow is this window, officially known as hypomania? And what if you’re a journalist whose reliability might be compromised by a tendency to see ominous patterns?)

I didn’t always get a sense of the specifics of Nevatia’s condition or what was so abnormal about it – in fact, one late passage, a record of his encounter with a smug-sounding doctor, had me wondering what was wrong with her (not least when she says what happened to him as a child “was incest, not abuse. You were a consenting partner”). Many of the “perilous” actions he lists at one point (“Accusing my parents of neglect, I had left home in a huff. I had openly berated the state and its control. I had sidled up to an Australian woman in a bikini. There was something obviously blasphemous about my presumed possession of divinity…”) didn’t seem extraordinarily deviant.

But that could be part of the point, since this book is part of an ongoing attempt to understand. As he puts it, manic depression is a sort of whodunit, “and the suspects are often many – genetic predisposition, chemical imbalances in the brain, environmental factors”. Were drugs the effect or a cause of his illness? Was the foundation laid in childhood? Can anyone know for sure?

The one thing to be certain of is that writing has performed a cathartic function for Nevatia. If it can be a sort of madness at times, it can also be a way of preserving sanity, holding on to ephemeral things (such as memories or opinions) and making sense of an unordered world.

-----------------------------------------

[A somewhat related post, about Jerry Pinto's Em and the Big Hoom, is here]

My father may have been an undiagnosed case of bipolarity - there definitely was a mental condition of some sort. And he wrote daily too. (A way of holding on to things, or convincing yourself that you’re sane?) There are still dozens of journals gathering dust in his house, and I can't look closely at them]

-----------------------

In my favourite chapter in

How to Travel Light

, Shreevatsa Nevatia’s memoir about his struggle with bipolarity, the author examines his relationship with films such as Apur Sansar and The Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. Discussing the scene in the former where the protagonist Apu stands in for a “mad groom” and marries a young girl he has never met before, Nevatia says that he sees two aspects of his own personality in these two men: Binu, delusional, clad in finery and destined to fall, and Apu, “scared and reluctant, but desirous of grandeur”.

In my favourite chapter in

How to Travel Light

, Shreevatsa Nevatia’s memoir about his struggle with bipolarity, the author examines his relationship with films such as Apur Sansar and The Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. Discussing the scene in the former where the protagonist Apu stands in for a “mad groom” and marries a young girl he has never met before, Nevatia says that he sees two aspects of his own personality in these two men: Binu, delusional, clad in finery and destined to fall, and Apu, “scared and reluctant, but desirous of grandeur”.To me, this passage – and what follows in the chapter – reads like intense, very personal film criticism of the sort I have special fondness for as a writer and reader. And a suggestion rears its head: obsessively finding patterns, connecting dots that most other people can’t see, locating yourself in gestures and lines of dialogue – all this may be a form of mental illness too. (Reviewers, beware.)

Other readers of How to Travel Light will undoubtedly find resonances in other chapters. They will probably find many things to admire, and a few things to be bored by, for a book like this is – to some degree at least – an exercise in navel-scratching. However well-written or insightful, there are passages that can seem of interest mainly to the author and the circle of family and friends who witnessed his ups and downs over the years.

Many people – friends, lovers, doctors, fellow sufferers, parents, siblings – flit through these pages, and one of the tics of Nevatia’s writing is to simply bring someone into the narrative by naming him or her, but without immediately explaining who this is. Add to this the fragmented, non-linear narrative – covering his many stints in rehab clinics, being sexually abused as a child by a cousin who was ten years older, the diagnosis of his condition in 2007, his ongoing attempts to give up drugs – and one gets the sense of a life lived in a blur, alternating between periods of rapture and depression.

Amidst all that chaos, there are startlingly vivid descriptions: Nevatia likens his isolation (and possible delusions of omniscience) to the terrifying Puranic image of Vishnu alone on his snake in an endless ocean. (Later, a memory of his grandmother dressing him up as the child Krishna is echoed in another Apur Sansar scene.) He tries to understand how his condition has affected his relationships. He mulls the social-media circus and how its momentary highs can make anyone seem potentially bipolar. And he circles back to the idea that many people need some “madness” to be able to do their best work, that the mind needs turbulence to thrive. (But how narrow is this window, officially known as hypomania? And what if you’re a journalist whose reliability might be compromised by a tendency to see ominous patterns?)

I didn’t always get a sense of the specifics of Nevatia’s condition or what was so abnormal about it – in fact, one late passage, a record of his encounter with a smug-sounding doctor, had me wondering what was wrong with her (not least when she says what happened to him as a child “was incest, not abuse. You were a consenting partner”). Many of the “perilous” actions he lists at one point (“Accusing my parents of neglect, I had left home in a huff. I had openly berated the state and its control. I had sidled up to an Australian woman in a bikini. There was something obviously blasphemous about my presumed possession of divinity…”) didn’t seem extraordinarily deviant.

But that could be part of the point, since this book is part of an ongoing attempt to understand. As he puts it, manic depression is a sort of whodunit, “and the suspects are often many – genetic predisposition, chemical imbalances in the brain, environmental factors”. Were drugs the effect or a cause of his illness? Was the foundation laid in childhood? Can anyone know for sure?

The one thing to be certain of is that writing has performed a cathartic function for Nevatia. If it can be a sort of madness at times, it can also be a way of preserving sanity, holding on to ephemeral things (such as memories or opinions) and making sense of an unordered world.

-----------------------------------------

[A somewhat related post, about Jerry Pinto's Em and the Big Hoom, is here]

Published on November 03, 2017 10:02

October 31, 2017

A call for help for Pratima Devi

This is an update - a composite of my social-media posts from the last two days - about Pratima Devi, the “kutton waali Amma” of the PVR Saket complex, whose house was demolished by the MCD on October 30, leaving her and dozens of dogs with no shelter just as the winter chill sets in. Yesterday, Ambika Shukla and her team got a makeshift tent constructed with tarpaulin, and we cleared up a lot of the rubble. The hope for the moment is that the MCD and the cops will let her stay under the tarpaulin for some time at least. Meanwhile we are looking at legal representation.

This is an update - a composite of my social-media posts from the last two days - about Pratima Devi, the “kutton waali Amma” of the PVR Saket complex, whose house was demolished by the MCD on October 30, leaving her and dozens of dogs with no shelter just as the winter chill sets in. Yesterday, Ambika Shukla and her team got a makeshift tent constructed with tarpaulin, and we cleared up a lot of the rubble. The hope for the moment is that the MCD and the cops will let her stay under the tarpaulin for some time at least. Meanwhile we are looking at legal representation.There has already been some media coverage; here are a few points that might provide context to anyone else who can help:

- For a few weeks, an MCD councillor has been harassing Amma with accusations that she is supplying drugs to little boys in the complex. I know this to be nonsense. A few years ago, when Amma was unwell and didn't have much support for dog-feeding etc, she allowed some kids and adolescents to hang around at her place, even sleep on her charpoys etc - in exchange for what help they could provide with looking after the animals - and some of these kids were addicts. This has made it easier to spread rumours about her.

- While the land she has been occupying obviously isn't hers, she has got certain papers including an Aadhar card with a "PVR complex" address, and an electricity bill in her name, with a meter.

- There were other official papers - I don't know all the details, but I saw a couple of them myself a few years ago - by the MCD, giving her permission to occupy a spot near the complex. Now, apparently, some of those papers have vanished. Amma and her son claim that the councillor bribed one of her helpers to steal them from her trunk. I don't want to take such accusations at face value, but it is of course a possibility.

- During an argument with some onlookers (including a parking attendant and a shopkeeper who have old grudges against Amma), I was told things like "She is polluting this posh complex by keeping all these dogs here." Similar claims have been repeated in a Times of India story today (November 1). Which is rubbish. More than anyone, she has helped in regulating the dog population (regular sterilisations and vaccinations are carried out) and in keeping them content and non-aggressive by feeding them.

Just after the demolitionIf the shopkeepers think the dogs are going to magically vanish if she is evicted, they are deluded; the MCD doesn’t have the authority to pick up stray dogs and dispose of them or relocate them. On the contrary, things will get much worse because now there will be dozens of frightened, hungry strays - used to being well looked after - who will encroach on the complex and surrounding areas, and make life very difficult for everyone. But maybe that is part of the plan: to build a stronger case against the very presence of street dogs.

Just after the demolitionIf the shopkeepers think the dogs are going to magically vanish if she is evicted, they are deluded; the MCD doesn’t have the authority to pick up stray dogs and dispose of them or relocate them. On the contrary, things will get much worse because now there will be dozens of frightened, hungry strays - used to being well looked after - who will encroach on the complex and surrounding areas, and make life very difficult for everyone. But maybe that is part of the plan: to build a stronger case against the very presence of street dogs.– Apart from those who have been kind enough to offer help in the form of money or provisions, for those of you in Delhi and with some time to spare: do go across and meet Amma sometime in the next few days, just for a short while. It’s important to show the people who are keeping an eye on her from a distance - cops, MCD, the market association - that she has plenty of support. Call me if you’re coming. I have a lot to handle at home and in hospital, and my time is never my own, but I can try to come by.

-------------

P.S. Amma has been written about in newspapers and featured on news channels in the past - see this piece in Mint Lounge, for example. And here is my first post about her from a few years ago.

Published on October 31, 2017 19:55

October 30, 2017

Suspense thriller or marital drama? Looking back at Ittefaq

[With the Ittefaq remake coming out this week, here's a piece I did for Film Companion about Yash Chopra's 1969 film]

--------------------------------

“Har paagal kabhi na kabhi akalmandi ki baat karta hai” (“Every madman has moments of sanity”)

– chuckling psychiatrist in the 1969 thriller Ittefaq

Yash Chopra’s Ittefaq centres on a “paagal”, a word repeatedly used to denote any sort of strange behaviour, and bandied about (even by senior doctors and cops) with the merry disregard for political correctness that we see in so many old films about mental illness.

It is fitting, then, that parts of Ittefaq play like scenes from a madman’s dream. Consider the cornucopia of bright colours and geometric designs that fill the screen for two minutes before the opening credits even appear. The influence of Saul Bass’s famous title designs for Hitchcock and other filmmakers is obvious, but it also feels a bit random, like some Rubik’s Cubes were tossed into a sabzi tray, chopped or grated, and the resulting fragments shot through a kaleidoscope. Anyway, no one would mistake the cheery background tune for one of Bernard Herrmann’s ominous compositions.

also feels a bit random, like some Rubik’s Cubes were tossed into a sabzi tray, chopped or grated, and the resulting fragments shot through a kaleidoscope. Anyway, no one would mistake the cheery background tune for one of Bernard Herrmann’s ominous compositions.

In its time, Ittefaq got much publicity for being a song-less Hindi film – but this doesn’t mean it was shorn of the other elements of our mainstream cinema. Unlike its relentlessly dark and gritty Western counterpart, the “Hindi-film noir” of the 1950s and 1960s was part of a tradition where many emotions and registers had to be mixed together. So there are tonal variations here, much juxtaposing of melodrama and studied restraint.

For instance, the opening sequence has a long, handheld-camera tracking shot from the POV of an artist named Dilip (Rajesh Khanna) as he enters his house. All very cinema-verite-like at this point, but then a zoom-in – accompanied by dramatic music – reveals the strangled corpse of Dilip’s wife, whereupon the camera whirls like a dervish and there is a spectacularly over-the-top, caterwauling performance by Khanna.

But in a suspense narrative like this, even theatrics do serve a purpose – we have to be on our guard, prepared that anything may be part of a subterfuge. The first thought that occurred to me was that the hysterical Dilip and his almost-equally-hysterical sister-in-law – who accuses him of murder – were putting on an act together. But there are other possibilities: Dilip is guilty and trying too hard to feign innocence; he killed his wife because he was mentally unstable (“paagal hai!”); he is innocent of murder but guilty of loving his art more than partying with his wife (“paagal hai!”); he killed her but then forgot about it because he had to finish a painting (“paagal! paagal! paagal!”).

Shortly afterwards, he escapes from a paagal-khana and breaks into a house where Rekha (Nanda) is alone, her husband away on a business trip. And now something intriguing happens. Even as the storm of a police pursuit rages outside, Ittefaq briefly becomes a two-person chamber drama of sorts.

After the initial wariness, Rekha and Dilip are soon chatting away like a married couple. There is a slow building of trust. “Bhaag toh nahin jaogi?” he asks her. “Abhi tak bharosa nahin?” she replies. They settle into a form of domesticity, bickering and making up; at one point, sounding like a hurt wife, she moans, “Maine tumhein kya takleef di?” Making a bed together at night, she playfully tosses a mattress at him. We are offered a vision of husbands and wives as jailers and qaidis to each other, shifting roles in turn.

After the initial wariness, Rekha and Dilip are soon chatting away like a married couple. There is a slow building of trust. “Bhaag toh nahin jaogi?” he asks her. “Abhi tak bharosa nahin?” she replies. They settle into a form of domesticity, bickering and making up; at one point, sounding like a hurt wife, she moans, “Maine tumhein kya takleef di?” Making a bed together at night, she playfully tosses a mattress at him. We are offered a vision of husbands and wives as jailers and qaidis to each other, shifting roles in turn.

And they confide in each other. Speaking of her (actual) husband, she says plaintively that there was a time when he was her dashing prince on horseback, but that the prince vanished within a few days. By the film’s end, this moment can be viewed as a red herring – diverting the viewer’s attention from what is really going on – but I prefer to take it at face value and to trust the genuineness of Rekha’s emotions.

There are, of course other things going on, including a bunch of elderly men sauntering about at 1 AM and laughing patronizingly when someone expresses fear of the “paagal” on the run. Despite the loophole-filled plot (and one delightful moment – for those of us who grew up making distasteful jokes about the large backsides of 1960s heroines – where Nanda’s sari-covered posterior becomes an important plot point, since it prevents a character from seeing something through a keyhole), the film manages to be gripping when it needs to be.

Ittefaq hasn’t aged too well if you’re a viewer who prefers the technical finesse and understatement of today’s multiplex Hindi film, so it is ripe for an updating – though the remake is likely to be very far in tone from the film Yash Chopra made. There will almost certainly be an extra twist or two, they will probably tone down the sentimental moral coda of the original, and “paagal” will be replaced by terms like “dopamine imbalance”. The doctors won’t openly laugh at their patients.

Plus, there will be no Rajesh Khanna, which means no subtextual analysis centred around one of our most popular screen personas. In the 1980 Red Rose , made long after he had lost most of his appeal as a romantic hero, Khanna was wittily cast as a serial killer-cum-playboy from whom no woman was safe. Ittefaq is in some ways the inverse of that film, with the young, boy-faced star as a pure-as-driven-snow victim of fate and coincidence, whose only crime may be overacting.

-----------------------

[Earlier posts on Rajesh Khanna: Red Rose; Shaitani Anand]

--------------------------------

“Har paagal kabhi na kabhi akalmandi ki baat karta hai” (“Every madman has moments of sanity”)

– chuckling psychiatrist in the 1969 thriller Ittefaq

Yash Chopra’s Ittefaq centres on a “paagal”, a word repeatedly used to denote any sort of strange behaviour, and bandied about (even by senior doctors and cops) with the merry disregard for political correctness that we see in so many old films about mental illness.

It is fitting, then, that parts of Ittefaq play like scenes from a madman’s dream. Consider the cornucopia of bright colours and geometric designs that fill the screen for two minutes before the opening credits even appear. The influence of Saul Bass’s famous title designs for Hitchcock and other filmmakers is obvious, but it

also feels a bit random, like some Rubik’s Cubes were tossed into a sabzi tray, chopped or grated, and the resulting fragments shot through a kaleidoscope. Anyway, no one would mistake the cheery background tune for one of Bernard Herrmann’s ominous compositions.

also feels a bit random, like some Rubik’s Cubes were tossed into a sabzi tray, chopped or grated, and the resulting fragments shot through a kaleidoscope. Anyway, no one would mistake the cheery background tune for one of Bernard Herrmann’s ominous compositions. In its time, Ittefaq got much publicity for being a song-less Hindi film – but this doesn’t mean it was shorn of the other elements of our mainstream cinema. Unlike its relentlessly dark and gritty Western counterpart, the “Hindi-film noir” of the 1950s and 1960s was part of a tradition where many emotions and registers had to be mixed together. So there are tonal variations here, much juxtaposing of melodrama and studied restraint.

For instance, the opening sequence has a long, handheld-camera tracking shot from the POV of an artist named Dilip (Rajesh Khanna) as he enters his house. All very cinema-verite-like at this point, but then a zoom-in – accompanied by dramatic music – reveals the strangled corpse of Dilip’s wife, whereupon the camera whirls like a dervish and there is a spectacularly over-the-top, caterwauling performance by Khanna.

But in a suspense narrative like this, even theatrics do serve a purpose – we have to be on our guard, prepared that anything may be part of a subterfuge. The first thought that occurred to me was that the hysterical Dilip and his almost-equally-hysterical sister-in-law – who accuses him of murder – were putting on an act together. But there are other possibilities: Dilip is guilty and trying too hard to feign innocence; he killed his wife because he was mentally unstable (“paagal hai!”); he is innocent of murder but guilty of loving his art more than partying with his wife (“paagal hai!”); he killed her but then forgot about it because he had to finish a painting (“paagal! paagal! paagal!”).

Shortly afterwards, he escapes from a paagal-khana and breaks into a house where Rekha (Nanda) is alone, her husband away on a business trip. And now something intriguing happens. Even as the storm of a police pursuit rages outside, Ittefaq briefly becomes a two-person chamber drama of sorts.

After the initial wariness, Rekha and Dilip are soon chatting away like a married couple. There is a slow building of trust. “Bhaag toh nahin jaogi?” he asks her. “Abhi tak bharosa nahin?” she replies. They settle into a form of domesticity, bickering and making up; at one point, sounding like a hurt wife, she moans, “Maine tumhein kya takleef di?” Making a bed together at night, she playfully tosses a mattress at him. We are offered a vision of husbands and wives as jailers and qaidis to each other, shifting roles in turn.

After the initial wariness, Rekha and Dilip are soon chatting away like a married couple. There is a slow building of trust. “Bhaag toh nahin jaogi?” he asks her. “Abhi tak bharosa nahin?” she replies. They settle into a form of domesticity, bickering and making up; at one point, sounding like a hurt wife, she moans, “Maine tumhein kya takleef di?” Making a bed together at night, she playfully tosses a mattress at him. We are offered a vision of husbands and wives as jailers and qaidis to each other, shifting roles in turn. And they confide in each other. Speaking of her (actual) husband, she says plaintively that there was a time when he was her dashing prince on horseback, but that the prince vanished within a few days. By the film’s end, this moment can be viewed as a red herring – diverting the viewer’s attention from what is really going on – but I prefer to take it at face value and to trust the genuineness of Rekha’s emotions.

There are, of course other things going on, including a bunch of elderly men sauntering about at 1 AM and laughing patronizingly when someone expresses fear of the “paagal” on the run. Despite the loophole-filled plot (and one delightful moment – for those of us who grew up making distasteful jokes about the large backsides of 1960s heroines – where Nanda’s sari-covered posterior becomes an important plot point, since it prevents a character from seeing something through a keyhole), the film manages to be gripping when it needs to be.

Ittefaq hasn’t aged too well if you’re a viewer who prefers the technical finesse and understatement of today’s multiplex Hindi film, so it is ripe for an updating – though the remake is likely to be very far in tone from the film Yash Chopra made. There will almost certainly be an extra twist or two, they will probably tone down the sentimental moral coda of the original, and “paagal” will be replaced by terms like “dopamine imbalance”. The doctors won’t openly laugh at their patients.

Plus, there will be no Rajesh Khanna, which means no subtextual analysis centred around one of our most popular screen personas. In the 1980 Red Rose , made long after he had lost most of his appeal as a romantic hero, Khanna was wittily cast as a serial killer-cum-playboy from whom no woman was safe. Ittefaq is in some ways the inverse of that film, with the young, boy-faced star as a pure-as-driven-snow victim of fate and coincidence, whose only crime may be overacting.

-----------------------

[Earlier posts on Rajesh Khanna: Red Rose; Shaitani Anand]

Published on October 30, 2017 07:43

October 24, 2017

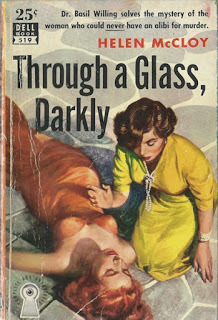

A young woman meets her other-self, Through a Glass, Darkly

[this is the second entry in my Scroll series about crime fiction. Previous piece here]

---------------------------------

In a key passage in Helen McCloy’s 1949 suspense novel Through a Glass, Darkly , a psychiatrist-detective is speaking with a young lady who is at the centre of a storm. Faustina Crayle has been dismissed from her teaching position in a girls’ school under a veil of secrecy, and Dr Basil Willing has discovered the reason: many terrified people believe that Faustina has unearthly powers; specifically, that she has a silent, ghostly double – or a doppelganger, to use the old German word. Whether Faustina herself is complicit in these spectral sightings – whether she is innocent or malicious – is beside the point for the school’s management. She can’t be allowed to stay on.

Now Basil and Faustina are talking, the former probing gently, the latter trying to make sense of all the disquiet she has caused. And she says:

investigation: he is Helen McCloy’s series detective.) A woman who is an object of suspicion for many of the characters is revealed as a sympathetic, sensitive and weary presence (though of course, we can’t yet be sure that Faustina isn’t other things as well). And then, after the man of science has reassured Faustina that she isn’t in mortal danger from a ghostly double, he walks out into the street, shivers, looks up at the night sky and says to himself: “Who am I to say what cannot happen in this unknowable world?”

investigation: he is Helen McCloy’s series detective.) A woman who is an object of suspicion for many of the characters is revealed as a sympathetic, sensitive and weary presence (though of course, we can’t yet be sure that Faustina isn’t other things as well). And then, after the man of science has reassured Faustina that she isn’t in mortal danger from a ghostly double, he walks out into the street, shivers, looks up at the night sky and says to himself: “Who am I to say what cannot happen in this unknowable world?”

At the very end of the book, someone else (I won’t reveal who) will make a similar gesture and pronouncement, and Willing himself will again be faced with self-doubt – even as he plays his role of the detective glibly winding things up.

******

Some months ago, when I began rekindling an old passion for crime writing, I found I hadn’t read several authors or books that were celebrated, even regarded as canonical, by serious genre buffs. It’s the sort of thing that can happen when, based on your familiarity with, say, Agatha Christie, Patricia Highsmith, Cornell Woolrich, Raymond Chandler and a few others – authors who tend to be well known to readers splashing about on the shores of the genre rather than plunging fully into it – you think you know almost everything there is to know about Anglophone crime writing of a certain vintage.