Jai Arjun Singh's Blog, page 41

February 5, 2018

Mini-review: teen runaways in The End of the F***ing World

[The 300/400-word “review” is not something I generally care for, but it’s fun to dabble in once in a while, and it does require its own discipline. Have been doing a few of these short pieces for India Today, a sort of throwback to my first journalistic bylines nearly 20 years ago. Here’s one on the new Netflix show The End of the F***ing World]

--------------

“I’m James. I’m 17. And I’m pretty sure I’m a psychopath,” are the first words we hear in this darkly offbeat Netflix show; one way of looking at

The End of the F***ing World

is that it is about a young man coming to discover that the world is more twisted than he could ever aspire to be. It must be deflating at that age to realise you aren’t all that special or dangerous; that even if you tortured animals as a kid and scalded your own hand in oil, there are much worse, less self-reflective people than you around.

“I’m James. I’m 17. And I’m pretty sure I’m a psychopath,” are the first words we hear in this darkly offbeat Netflix show; one way of looking at

The End of the F***ing World

is that it is about a young man coming to discover that the world is more twisted than he could ever aspire to be. It must be deflating at that age to realise you aren’t all that special or dangerous; that even if you tortured animals as a kid and scalded your own hand in oil, there are much worse, less self-reflective people than you around.

This tightly constructed, easy-to-binge-watch British series (with eight episodes of around 20 minutes each) centres on James and Alyssa, his restless and depressive new friend -- if that’s the correct description for someone whom he plans to kill (or so he claims). They agree to run away, leaving behind the town where they feel like misfits. “If this was a film, we’d probably be American,” Alyssa deadpans with the wisdom of one familiar with the Hollywood tradition of malcontents on the road, which stretches back at least to Nicholas Ray’s 1948 classic They Live by Night and includes Terrence Malick’s Badlands and Tony Scott’s True Romance.

At first, these two seem like cold fish -- desultory, blank-faced, with a mechanical and bored attitude to everything, even sex. (James seems only marginally more enthusiastic about killing Alyssa, but keeps putting it off – and if you look at that as an inability to commit, what you have here is a macabre love story.) But soon, circumstances bring out their vulnerable sides -- the first three episodes give us two nasty middle-aged men whose behaviour makes these kids seem like, well, kids -- and they become easier to care about.

I had heard this was a black comedy and was a little disappointed on that score -- there is some dry, morose humour (one high point involves a sad-faced gas-station attendant named Frodo, who looks like a very young version of Pink Floyd legend David Gilmore), but not as much as I had hoped for. There are other things to enjoy, though, notably the lead performances by Alex Lawther and Jessica Barden, a rock soundtrack that uses classics like “I’m laughing on the outside, crying on the inside” to unusual effect, and (if you’re into this sort of thing) a stylized murder scene with blood flowing dreamily at the camera. At times, the voiceover-driven narrative does come across as pretentiously, show-offishly nihilistic; but you’d expect an angst-ridden teen to be like that.

--------------

“I’m James. I’m 17. And I’m pretty sure I’m a psychopath,” are the first words we hear in this darkly offbeat Netflix show; one way of looking at

The End of the F***ing World

is that it is about a young man coming to discover that the world is more twisted than he could ever aspire to be. It must be deflating at that age to realise you aren’t all that special or dangerous; that even if you tortured animals as a kid and scalded your own hand in oil, there are much worse, less self-reflective people than you around.

“I’m James. I’m 17. And I’m pretty sure I’m a psychopath,” are the first words we hear in this darkly offbeat Netflix show; one way of looking at

The End of the F***ing World

is that it is about a young man coming to discover that the world is more twisted than he could ever aspire to be. It must be deflating at that age to realise you aren’t all that special or dangerous; that even if you tortured animals as a kid and scalded your own hand in oil, there are much worse, less self-reflective people than you around. This tightly constructed, easy-to-binge-watch British series (with eight episodes of around 20 minutes each) centres on James and Alyssa, his restless and depressive new friend -- if that’s the correct description for someone whom he plans to kill (or so he claims). They agree to run away, leaving behind the town where they feel like misfits. “If this was a film, we’d probably be American,” Alyssa deadpans with the wisdom of one familiar with the Hollywood tradition of malcontents on the road, which stretches back at least to Nicholas Ray’s 1948 classic They Live by Night and includes Terrence Malick’s Badlands and Tony Scott’s True Romance.

At first, these two seem like cold fish -- desultory, blank-faced, with a mechanical and bored attitude to everything, even sex. (James seems only marginally more enthusiastic about killing Alyssa, but keeps putting it off – and if you look at that as an inability to commit, what you have here is a macabre love story.) But soon, circumstances bring out their vulnerable sides -- the first three episodes give us two nasty middle-aged men whose behaviour makes these kids seem like, well, kids -- and they become easier to care about.

I had heard this was a black comedy and was a little disappointed on that score -- there is some dry, morose humour (one high point involves a sad-faced gas-station attendant named Frodo, who looks like a very young version of Pink Floyd legend David Gilmore), but not as much as I had hoped for. There are other things to enjoy, though, notably the lead performances by Alex Lawther and Jessica Barden, a rock soundtrack that uses classics like “I’m laughing on the outside, crying on the inside” to unusual effect, and (if you’re into this sort of thing) a stylized murder scene with blood flowing dreamily at the camera. At times, the voiceover-driven narrative does come across as pretentiously, show-offishly nihilistic; but you’d expect an angst-ridden teen to be like that.

Published on February 05, 2018 18:53

January 20, 2018

Bad parents, problem children: Frankenstein at the movies

[Did this piece for Mint Lounge as part of their “200 years of Frankenstein” package]

Among the many ways of looking at Frankenstein, and by “Frankenstein” one necessarily means not just Mary Shelley’s groundbreaking book but what that book birthed over two hundred years – as other authors, playwrights, theatre producers and filmmakers prodded away at it, moving body parts around in their sinister laboratories – here is one interpretation. It is about terrible and unhappy parents, terrible and unhappy children, and how, to misquote Philip Larkin, we pass misery back and forth.

You’re Victor Frankenstein, you think you’ve done your best, but here’s this monster you created, which refuses to be what you hoped it would be. Worse, it turns around and blames you for everything that’s wrong. Look at the Paradise Lost line – “Did I request thee, Maker, from my clay, to mould me Man?” – which serves as an epigraph for Mary Shelley’s novel, and then listen to director Guillermo del Toro, who is currently working on a Frankenstein film: "It’s the quintessential teenage book. You don't belong. You were brought to this world by people that don't care for you and you are thrown into a world of tears and hunger.”

Most parent-child relationships, when looked at over a period of time, bring high tragedy and slapstick comedy together in the same frame. Little wonder then that cinematic Frankensteins have inhabited every mode from deep seriousness to goofy, pseudo-science-driven humour – and that the most enduring films accommodate both extremes.

Consider one of the most effective scenes, gentle, idyllic and horrifying all at once, in James Whale’s 1931 Frankenstein. Boris Karloff’s Monster comes across a little girl, joins her in placing flowers on a lake’s surface and watching them float – and then, in all innocence, dunks her into the water too, causing her death. So iconic was this moment – often censored in early screenings – that forty years later the Spanish director Victor Erice made it the focal point of his coming-of-age narrative The Spirit of the Beehive : the six-year-old protagonist Ana is traumatised when she watches the scene; in the days that follow, she becomes aware of subtler monsters in her own world.

Or see Whale’s 1935 sequel, Bride of Frankenstein, in which Karloff’s plaintiveness – as the Monster yearns for a companion who will love and understand him – brushes up against Elsa Lanchester’s brief but delightfully lunatic performance as his bride-not-to-be (the actress also played Mary Shelley in a short scene, so impishly you wondered if she was plotting to capsize Percy Bysshe’s boat).

Or see Whale’s 1935 sequel, Bride of Frankenstein, in which Karloff’s plaintiveness – as the Monster yearns for a companion who will love and understand him – brushes up against Elsa Lanchester’s brief but delightfully lunatic performance as his bride-not-to-be (the actress also played Mary Shelley in a short scene, so impishly you wondered if she was plotting to capsize Percy Bysshe’s boat).

Those are still the two best-known Frankenstein films, and to modern eyes they can seem creaky and overwrought. Taking cues from theatre adaptations staged in Mary Shelley’s lifetime, they turned Victor Frankenstein into the prototype of the mad scientist, shrieking that he knows what it’s like “to be God” (in the book he is a diligent, conscientious man). But Karloff’s performance helps erase some of the differences. While the creature in Shelley’s novel gains in eloquence and dignity once he learns to use language, the “dumb” movie Monster is sympathetic by other means, conveying childlike pathos through his gestures and expressions. In fact, one can argue that in the broader-comedy scenes where he grunts words – the refrain of “Good! Good!” when an old hermit makes him taste bread and wine – he becomes less likable.

Of course, there are other films where the Monster is not meant to be at all likable – see the 1957 Curse of Frankenstein, starring those two masters of the Hammer Horror franchise, Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee, and watch Lee play the role as a deformed, inexpressive zombie, starting with the shocking moment where he rips the bandages off his face as the camera zooms in on him.

Another dominant mode is that of parody mixed with affection for the source material. Mel Brooks’s 1974 Young Frankenstein, shot in atmospheric black and white, has madcap scenes like the one where the doctor’s assistant brings along a brain labeled “Abnormal” – thinking it belonged to someone named “Abbie Normal” – but the film also understands the sense of wonder and danger that permeates the original story. This is equally true of three 1980s films – Gothic, Haunted Summer and Rowing with the Wind – which aren’t straight renderings of the Frankenstein tale but dramatize the famous 1816 summer house party involving the Shelleys and Lord Byron, where both Frankenstein and the John Polidori horror story “The Vampyre” were conceived.

And, of course, there are “serious” Frankenstein movies, which usually err on the side of earnestness. Kenneth Branagh’s 1994 Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein set out to be faithful to the book, in a way the Karloff films never did, but the promise was marred by half-hearted execution – and ironically its best moments were the more inventive ones such as the scene where the naked creature (played by Robert De Niro, channeling a middle-aged Travis Bickle) slips about like a newborn baby in what looks like amniotic fluid.

half-hearted execution – and ironically its best moments were the more inventive ones such as the scene where the naked creature (played by Robert De Niro, channeling a middle-aged Travis Bickle) slips about like a newborn baby in what looks like amniotic fluid.

Frankenstein is often regarded as the first true science-fiction novel, and this perception has become increasingly relevant in our time, where artificial intelligence has taken on forms that Mary Shelley couldn’t have envisioned. The idea of an imitation human being more humane in some ways than the flesh-and-blood people around him is a theme that has informed a lot of modern sci-fi about automatons: from the replicants in Blade Runner to the 1999 Bicentennial Man (adapted from Isaac Asimov’s The Positronic Man) and Steven Spielberg’s A.I. Artificial Intelligence (based on Brian Aldiss’s Supertoys Last all Summer Long, and often seen as a futuristic version of the Pinocchio story).

But it’s just as instructive to go back in time, to two decades before the Karloff films, when a 12-minute Frankenstein was made by Thomas Edison’s studio in 1910. Watching this relic (you’ll find it on YouTube) is like getting into a time machine: given that the world of the Shelleys seems so impossibly distant to us today, it’s unsettling to realise that the Edison film is closer in time (a mere 92 years) to the publication of the book than to our present day.

What I find fascinating about that ancient film – as a cinema student and as someone who thinks of the Frankenstein story as being rooted in honest scientific curiosity – is how much it does with the very limited motion-picture technology of the time. For instance, for the challenging scene in which the monster comes alive, a wax replica of a skeleton was placed in a vat and set afire until it dissolved and crumpled. They then played the film backward, so that the impression we get is of something hideous being forged out of fire and sitting upright after its limbs have formed.

To watch that scene is to think of the imagination and daring required of early filmmakers when they wanted to do something more ambitious than simply record reality. One could say those pioneers were kindred spirits of Victor Frankenstein, tinkering in their workshops until their children grew and became something vast and uncontrollable, slipping out of their Godlike hands.

-------------------------------------

[Related posts: Erice's The Spirit of the Beehive; Draupadi and the bride of Frankenstein]

Among the many ways of looking at Frankenstein, and by “Frankenstein” one necessarily means not just Mary Shelley’s groundbreaking book but what that book birthed over two hundred years – as other authors, playwrights, theatre producers and filmmakers prodded away at it, moving body parts around in their sinister laboratories – here is one interpretation. It is about terrible and unhappy parents, terrible and unhappy children, and how, to misquote Philip Larkin, we pass misery back and forth.

You’re Victor Frankenstein, you think you’ve done your best, but here’s this monster you created, which refuses to be what you hoped it would be. Worse, it turns around and blames you for everything that’s wrong. Look at the Paradise Lost line – “Did I request thee, Maker, from my clay, to mould me Man?” – which serves as an epigraph for Mary Shelley’s novel, and then listen to director Guillermo del Toro, who is currently working on a Frankenstein film: "It’s the quintessential teenage book. You don't belong. You were brought to this world by people that don't care for you and you are thrown into a world of tears and hunger.”

Most parent-child relationships, when looked at over a period of time, bring high tragedy and slapstick comedy together in the same frame. Little wonder then that cinematic Frankensteins have inhabited every mode from deep seriousness to goofy, pseudo-science-driven humour – and that the most enduring films accommodate both extremes.

Consider one of the most effective scenes, gentle, idyllic and horrifying all at once, in James Whale’s 1931 Frankenstein. Boris Karloff’s Monster comes across a little girl, joins her in placing flowers on a lake’s surface and watching them float – and then, in all innocence, dunks her into the water too, causing her death. So iconic was this moment – often censored in early screenings – that forty years later the Spanish director Victor Erice made it the focal point of his coming-of-age narrative The Spirit of the Beehive : the six-year-old protagonist Ana is traumatised when she watches the scene; in the days that follow, she becomes aware of subtler monsters in her own world.

Or see Whale’s 1935 sequel, Bride of Frankenstein, in which Karloff’s plaintiveness – as the Monster yearns for a companion who will love and understand him – brushes up against Elsa Lanchester’s brief but delightfully lunatic performance as his bride-not-to-be (the actress also played Mary Shelley in a short scene, so impishly you wondered if she was plotting to capsize Percy Bysshe’s boat).

Or see Whale’s 1935 sequel, Bride of Frankenstein, in which Karloff’s plaintiveness – as the Monster yearns for a companion who will love and understand him – brushes up against Elsa Lanchester’s brief but delightfully lunatic performance as his bride-not-to-be (the actress also played Mary Shelley in a short scene, so impishly you wondered if she was plotting to capsize Percy Bysshe’s boat).Those are still the two best-known Frankenstein films, and to modern eyes they can seem creaky and overwrought. Taking cues from theatre adaptations staged in Mary Shelley’s lifetime, they turned Victor Frankenstein into the prototype of the mad scientist, shrieking that he knows what it’s like “to be God” (in the book he is a diligent, conscientious man). But Karloff’s performance helps erase some of the differences. While the creature in Shelley’s novel gains in eloquence and dignity once he learns to use language, the “dumb” movie Monster is sympathetic by other means, conveying childlike pathos through his gestures and expressions. In fact, one can argue that in the broader-comedy scenes where he grunts words – the refrain of “Good! Good!” when an old hermit makes him taste bread and wine – he becomes less likable.

Of course, there are other films where the Monster is not meant to be at all likable – see the 1957 Curse of Frankenstein, starring those two masters of the Hammer Horror franchise, Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee, and watch Lee play the role as a deformed, inexpressive zombie, starting with the shocking moment where he rips the bandages off his face as the camera zooms in on him.

Another dominant mode is that of parody mixed with affection for the source material. Mel Brooks’s 1974 Young Frankenstein, shot in atmospheric black and white, has madcap scenes like the one where the doctor’s assistant brings along a brain labeled “Abnormal” – thinking it belonged to someone named “Abbie Normal” – but the film also understands the sense of wonder and danger that permeates the original story. This is equally true of three 1980s films – Gothic, Haunted Summer and Rowing with the Wind – which aren’t straight renderings of the Frankenstein tale but dramatize the famous 1816 summer house party involving the Shelleys and Lord Byron, where both Frankenstein and the John Polidori horror story “The Vampyre” were conceived.

And, of course, there are “serious” Frankenstein movies, which usually err on the side of earnestness. Kenneth Branagh’s 1994 Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein set out to be faithful to the book, in a way the Karloff films never did, but the promise was marred by

half-hearted execution – and ironically its best moments were the more inventive ones such as the scene where the naked creature (played by Robert De Niro, channeling a middle-aged Travis Bickle) slips about like a newborn baby in what looks like amniotic fluid.

half-hearted execution – and ironically its best moments were the more inventive ones such as the scene where the naked creature (played by Robert De Niro, channeling a middle-aged Travis Bickle) slips about like a newborn baby in what looks like amniotic fluid.Frankenstein is often regarded as the first true science-fiction novel, and this perception has become increasingly relevant in our time, where artificial intelligence has taken on forms that Mary Shelley couldn’t have envisioned. The idea of an imitation human being more humane in some ways than the flesh-and-blood people around him is a theme that has informed a lot of modern sci-fi about automatons: from the replicants in Blade Runner to the 1999 Bicentennial Man (adapted from Isaac Asimov’s The Positronic Man) and Steven Spielberg’s A.I. Artificial Intelligence (based on Brian Aldiss’s Supertoys Last all Summer Long, and often seen as a futuristic version of the Pinocchio story).

But it’s just as instructive to go back in time, to two decades before the Karloff films, when a 12-minute Frankenstein was made by Thomas Edison’s studio in 1910. Watching this relic (you’ll find it on YouTube) is like getting into a time machine: given that the world of the Shelleys seems so impossibly distant to us today, it’s unsettling to realise that the Edison film is closer in time (a mere 92 years) to the publication of the book than to our present day.

What I find fascinating about that ancient film – as a cinema student and as someone who thinks of the Frankenstein story as being rooted in honest scientific curiosity – is how much it does with the very limited motion-picture technology of the time. For instance, for the challenging scene in which the monster comes alive, a wax replica of a skeleton was placed in a vat and set afire until it dissolved and crumpled. They then played the film backward, so that the impression we get is of something hideous being forged out of fire and sitting upright after its limbs have formed.

To watch that scene is to think of the imagination and daring required of early filmmakers when they wanted to do something more ambitious than simply record reality. One could say those pioneers were kindred spirits of Victor Frankenstein, tinkering in their workshops until their children grew and became something vast and uncontrollable, slipping out of their Godlike hands.

-------------------------------------

[Related posts: Erice's The Spirit of the Beehive; Draupadi and the bride of Frankenstein]

Published on January 20, 2018 07:28

January 8, 2018

Rahi Masoom Raza’s Scene 75: death of a writer foretold

[did this review – of the English translation of Raza’s savagely funny 1977 novel – for Scroll]

------------------------------------------------------------------

But Raza was also a “serious writer” (in the generally used, narrow sense of that term), the author of acclaimed books such as Aadha Gaon and Topi Shukla – and like many others negotiating the world of commercial Hindi cinema, he would have had to balance his individualistic side with the more formulaic demands made on him. In the best cases, such marriages could result in fine films which combined surface lightness with thematic depth, bringing together the strengths of two mediums. In many other cases, a writer could feel stymied, exploited and unappreciated.

This conflict informs his 1977 novel Scene 75, which has just been translated into English by Poonam Saxena, and in an early passage of which we find a writer struggling with a film scene. But he couldn’t understand “Scene: 75: Day: Post Office”. And [the director] was not wrong in asking him why he couldn’t understand it, because were there any scenes in commercial Hindi cinema that one couldn’t understand? The scene in question involves Sanjeev Kumar playing a roadside munshi and Leela Mishra as an old woman dictating a letter to him; the book will have many other references – including some very funny ones – to real-life actors and writers (even Raza himself).

This conflict informs his 1977 novel Scene 75, which has just been translated into English by Poonam Saxena, and in an early passage of which we find a writer struggling with a film scene. But he couldn’t understand “Scene: 75: Day: Post Office”. And [the director] was not wrong in asking him why he couldn’t understand it, because were there any scenes in commercial Hindi cinema that one couldn’t understand? The scene in question involves Sanjeev Kumar playing a roadside munshi and Leela Mishra as an old woman dictating a letter to him; the book will have many other references – including some very funny ones – to real-life actors and writers (even Raza himself).

Scene 75 can broadly be described as a story about a writer named Ali Amjad, who comes from Benares to Bombay to work in films. That synopsis doesn’t begin to convey the book’s tone and effect, though; this slim, conversational novel is also a complex beast that demands a reader’s full attention. This is because Raza approaches his themes (the marginalization of the writer, the many duplicities of the world) in a roundabout, non-chronological way by evoking the world around Ali Amjad, including the many colourful personalities whose lives are interlinked: his three roommates in the guesthouse he stays in when he first arrives in Bombay, his neighbours in the housing society he later moves to.

In fact, for large, entertaining chunks of the book, we barely hear anything about its “protagonist”, but we know he is around, watching and absorbing. The things he sees and hears provide him with material as a writer, but also add to his despair.

****

The book’s preface includes these lines from a Raza poem – “Whoever you see / Whoever you meet / They seem like someone else / In this neighbourhood / It’s as if no one has an identity” – and the question of identity runs through the story. People wear masks, pretend to be what they are not. A Muslim adopts a Hindu identity so he can get a job in a prejudice-ridden society complex. A Hindu wears a suit and a new name and goes to church with his Catholic girlfriend. Neighbours become secret lovers while maintaining outward facades. A long-married woman is a lesbian who slides her hands all over a friend’s body on the pretext of teaching her how to tie a sari properly. (The friend gets something out of it too – she learns how to tie a sari.) A young woman begins an affair with one of her father’s employees, and is soon in something close to a ménage-a-trois with her own mother.

Elsewhere, an assistant bill collector who gets paid Rs 192 a month pretends to be a sales supervisor earning many times more, and must weave a tangled web when he is in danger of getting found out. Another man, we are told, plays three roles, as a homeopathic doctor, a writer and a husband: “All three were full-time jobs, but Guptaji did them in such a way that none of the three knew about the others.”

All this reminded me of the pretence-and-masquerade themes that were so common in the Middle Cinema that Raza was associated with; the grappling – often in lighthearted contexts – with the idea of what is real and what is illusory, and how the twain might meet. Reading about the Ramnath who becomes a Peter Singh, one remembers that in this same period Raza was writing for films like Gol Maal , with lines like “Jo milte hain, woh nahi milte, aur jo nahi milte, wohi vaastav mein milte hain […] isi hone na hone, milne na milne ke beech, ek maya ka samudra hai.” (“Those who meet don’t really meet, and those who do not meet are in reality meeting […] and between this being and not being, meeting and not meeting, is a sea of illusion.”)

It’s just about possible to imagine some of Scene 75’s characters, their activities toned down, glimpsed on the periphery of a 1970s Hindi film – the many residents of the multistoreyed building in Mili, for instance, each bearing quirks and secrets. But there are scenes and lines in this novel – as it portrays religious and class divides, social aspiration and sexual transgressions with sharp, dry humour – that you wouldn’t find in a mainstream Hindi film of the period.

Besides, the narrative structure is closer to other, more experimental cinemas of the time: like Luis Bunuel’s The Phantom of Liberty or The Milky Way, which follow first one set of characters, then take a sudden detour to track someone else, and so on (“it's like the camera is telling the viewer, hmm, this new person might have an even more interesting story, so let's take a chance and see what he's up to," Bunuel’s screenwriter Jean-Claude Carriere told me years ago). For example, at one point in Raza’s novel, two friends are laughing about something but then the narrative takes us into the kitchen of the same house where the maid is also giggling with her boyfriend – and then we get the back-story of this new character. Which means we must follow the narrative closely to figure out what is happening at what point, or whether we have returned to the present from a flashback.

This sinuousness, and the “dense forest of names” that Ali Amjad finds himself beset by, couldn’t have made the translator’s task easy; Saxena also notes that Raza was sometimes careless with details and continuity. But she persevered and did a fine job of capturing the earthy humour that must have had a very specific flavour in the original Hindi. I found myself mentally re-translating bits like this one: “Midha liked bill collector Bholaram’s wife, Rama. Her skin was pale like a champa flower. Her eyes looked as if they understood the language of eyes.”

Some passages can seem as raw and unstructured at first as a scene from a hurriedly made 1970s Hindi film, but have a similar truth and directness that will stay with you. As for the throwaway observations that are hilarious and cuttingly sad at once, there are too many to list – but here’s one:

------------------------------------------------------------------

"The world of Hindi films is a world of incomplete people. Here, when two people come together, they don’t multiply. They become one."To pre-millennial urban Indians who grew up reading mainly in English while also watching Hindi cinema, Rahi Masoom Raza is best known not as a novelist and poet but as the dialogue writer of the 1980s television Mahabharat, as well as many 1970s and 1980s movies. Looking up his filmography, I was delighted to find that in addition to winning awards for reasonably well-respected films like Yash Chopra’s Lamhe and Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s Mili, he worked on some of my more disreputable childhood favourites such as Dance Dance and Adventures of Tarzan.

But Raza was also a “serious writer” (in the generally used, narrow sense of that term), the author of acclaimed books such as Aadha Gaon and Topi Shukla – and like many others negotiating the world of commercial Hindi cinema, he would have had to balance his individualistic side with the more formulaic demands made on him. In the best cases, such marriages could result in fine films which combined surface lightness with thematic depth, bringing together the strengths of two mediums. In many other cases, a writer could feel stymied, exploited and unappreciated.

This conflict informs his 1977 novel Scene 75, which has just been translated into English by Poonam Saxena, and in an early passage of which we find a writer struggling with a film scene. But he couldn’t understand “Scene: 75: Day: Post Office”. And [the director] was not wrong in asking him why he couldn’t understand it, because were there any scenes in commercial Hindi cinema that one couldn’t understand? The scene in question involves Sanjeev Kumar playing a roadside munshi and Leela Mishra as an old woman dictating a letter to him; the book will have many other references – including some very funny ones – to real-life actors and writers (even Raza himself).

This conflict informs his 1977 novel Scene 75, which has just been translated into English by Poonam Saxena, and in an early passage of which we find a writer struggling with a film scene. But he couldn’t understand “Scene: 75: Day: Post Office”. And [the director] was not wrong in asking him why he couldn’t understand it, because were there any scenes in commercial Hindi cinema that one couldn’t understand? The scene in question involves Sanjeev Kumar playing a roadside munshi and Leela Mishra as an old woman dictating a letter to him; the book will have many other references – including some very funny ones – to real-life actors and writers (even Raza himself). Scene 75 can broadly be described as a story about a writer named Ali Amjad, who comes from Benares to Bombay to work in films. That synopsis doesn’t begin to convey the book’s tone and effect, though; this slim, conversational novel is also a complex beast that demands a reader’s full attention. This is because Raza approaches his themes (the marginalization of the writer, the many duplicities of the world) in a roundabout, non-chronological way by evoking the world around Ali Amjad, including the many colourful personalities whose lives are interlinked: his three roommates in the guesthouse he stays in when he first arrives in Bombay, his neighbours in the housing society he later moves to.

In fact, for large, entertaining chunks of the book, we barely hear anything about its “protagonist”, but we know he is around, watching and absorbing. The things he sees and hears provide him with material as a writer, but also add to his despair.

****

The book’s preface includes these lines from a Raza poem – “Whoever you see / Whoever you meet / They seem like someone else / In this neighbourhood / It’s as if no one has an identity” – and the question of identity runs through the story. People wear masks, pretend to be what they are not. A Muslim adopts a Hindu identity so he can get a job in a prejudice-ridden society complex. A Hindu wears a suit and a new name and goes to church with his Catholic girlfriend. Neighbours become secret lovers while maintaining outward facades. A long-married woman is a lesbian who slides her hands all over a friend’s body on the pretext of teaching her how to tie a sari properly. (The friend gets something out of it too – she learns how to tie a sari.) A young woman begins an affair with one of her father’s employees, and is soon in something close to a ménage-a-trois with her own mother.

Elsewhere, an assistant bill collector who gets paid Rs 192 a month pretends to be a sales supervisor earning many times more, and must weave a tangled web when he is in danger of getting found out. Another man, we are told, plays three roles, as a homeopathic doctor, a writer and a husband: “All three were full-time jobs, but Guptaji did them in such a way that none of the three knew about the others.”

All this reminded me of the pretence-and-masquerade themes that were so common in the Middle Cinema that Raza was associated with; the grappling – often in lighthearted contexts – with the idea of what is real and what is illusory, and how the twain might meet. Reading about the Ramnath who becomes a Peter Singh, one remembers that in this same period Raza was writing for films like Gol Maal , with lines like “Jo milte hain, woh nahi milte, aur jo nahi milte, wohi vaastav mein milte hain […] isi hone na hone, milne na milne ke beech, ek maya ka samudra hai.” (“Those who meet don’t really meet, and those who do not meet are in reality meeting […] and between this being and not being, meeting and not meeting, is a sea of illusion.”)

It’s just about possible to imagine some of Scene 75’s characters, their activities toned down, glimpsed on the periphery of a 1970s Hindi film – the many residents of the multistoreyed building in Mili, for instance, each bearing quirks and secrets. But there are scenes and lines in this novel – as it portrays religious and class divides, social aspiration and sexual transgressions with sharp, dry humour – that you wouldn’t find in a mainstream Hindi film of the period.

Besides, the narrative structure is closer to other, more experimental cinemas of the time: like Luis Bunuel’s The Phantom of Liberty or The Milky Way, which follow first one set of characters, then take a sudden detour to track someone else, and so on (“it's like the camera is telling the viewer, hmm, this new person might have an even more interesting story, so let's take a chance and see what he's up to," Bunuel’s screenwriter Jean-Claude Carriere told me years ago). For example, at one point in Raza’s novel, two friends are laughing about something but then the narrative takes us into the kitchen of the same house where the maid is also giggling with her boyfriend – and then we get the back-story of this new character. Which means we must follow the narrative closely to figure out what is happening at what point, or whether we have returned to the present from a flashback.

This sinuousness, and the “dense forest of names” that Ali Amjad finds himself beset by, couldn’t have made the translator’s task easy; Saxena also notes that Raza was sometimes careless with details and continuity. But she persevered and did a fine job of capturing the earthy humour that must have had a very specific flavour in the original Hindi. I found myself mentally re-translating bits like this one: “Midha liked bill collector Bholaram’s wife, Rama. Her skin was pale like a champa flower. Her eyes looked as if they understood the language of eyes.”

Some passages can seem as raw and unstructured at first as a scene from a hurriedly made 1970s Hindi film, but have a similar truth and directness that will stay with you. As for the throwaway observations that are hilarious and cuttingly sad at once, there are too many to list – but here’s one:

Lisa placed her hand on Ramnath’s lips and he kissed it. He had learnt all this from watching Hindi films.Eventually, in a surreal yet credible turn of events, Ali Amjad finds himself working as a scriptwriter not for movies (good or bad) but for a beggars’ workshop. This makes a poetic kind of sense, given everything that has preceded it. And it leads to a melancholy, dreamlike final segment that prepares us for a writer’s death. The question of how he dies, and whether the death is literal or metaphorical or both, is almost irrelevant. The bigger question – addressed in the book’s searing final paragraph – is: does anyone care?

“If you marry me, where will you keep me?”

“In my heart,” Ramnath said, thumping his chest.

“Where will I go to the bathroom?”

Ramnath had no answer to this question.

Published on January 08, 2018 23:37

January 5, 2018

Looking ahead by looking back? A TV wish-list for the Hindi-film buff

[did this piece for Mint Lounge]

-----------------------

Most film buffs agree that the well-made long-form series (including web shows where a season’s worth of episodes might be released at one go) has outshone cinema in many ways. I’m a relative newbie to this world, but after having watched only a few such shows – The Crown and Mindhunter among them – the medium’s strengths are obvious: complex, carefully planned narrative arcs (writers often schematize a story so that a later episode makes you view a much earlier one in a new, more poignant light), the versatile and often contrapuntal use of music (Mindhunter’s first season ends by using the Led Zeppelin classic “In the Light” in ways that defy all our soundtrack instincts – yet it is brilliant), the occasional experimenting with episodes that work as self-contained mini-films.

Little wonder then that for Indian cineastes and book lovers, two of the most keenly anticipated events of this year are the Netflix adaptation of Vikram Chandra’s cops-and-gangsters novel Sacred Games – this series brings together such heavyweights as Anurag Kashyap, Vikramaditya Motwane, Saif Ali Khan and Nawazuddin Siddiqui – and the eight-part BBC series of another literary door-stopper, Vikram Seth’s A Suitable Boy. These sprawling novels deserve such a format.

What other Indian narratives could make for great TV or online shows? There are obvious stories in our literature, from ancient epics (and their many contemporary retellings or perspective tellings) to modern novels with a big canvas. But speaking as a film-history nerd who recently encountered the show Feud (about the Bette Davis-Joan Crawford rivalry), my “to be developed in 2018” wishlist would include any well-dramatized story about the Hindi film industry of the 1940s and 1950s.

There is plenty of promising source material (though authenticity may be in question). Consider Dev Anand’s deliciously florid autobiography Romancing With Life , which often reads like a screenplay complete with full-fledged conversations, and scenes such as the one where the young Dev meets his idol Ashok Kumar (who keeps blowing cigarette smoke into his face) or has a last, weepy rooftop tryst with forbidden love Suraiya. Or take Saadat Hasan Manto’s gossipy, irreverent accounts of stars and directors.

screenplay complete with full-fledged conversations, and scenes such as the one where the young Dev meets his idol Ashok Kumar (who keeps blowing cigarette smoke into his face) or has a last, weepy rooftop tryst with forbidden love Suraiya. Or take Saadat Hasan Manto’s gossipy, irreverent accounts of stars and directors.

Many of our major films have also had riveting back-stories: I can just about picture a limited series about the making of Mughal-e-Azam or Mother India or Sholay. Or Guide! The comic possibilities in an episode about RK Narayan’s growing dismay as his quiet Malgudi-based story is turned into a glamorous, pan-India spectacle are practically endless – and much of the material for this is already laid out in a sardonic essay that Narayan wrote about the experience.

Speaking of which, there is rich material in the travails of writers who worked in Hindi cinema – including those who sometimes had to strike a balance between their highbrow impulses and the formulaic demands made on them. Rahi Masoom Raza’s novel Scene 75 – just translated into English by Poonam Saxena – provides a sharply entertaining look at such people on the fringes of an industry where even a prominent writer’s sudden death must not be allowed to interfere with the joviality of a premiere.

Of course, such real-life narratives can be laced with a bit of “what if”, as the critic David Thomson did in an essay titled “James Dean at 50”, imagining a middle-aged version of the Rebel Without a Cause star (in reality, Dean died in his twenties). Some speculative fiction along those lines: what if Guru Dutt had lived and gone on to make more Pyaasa and Kaagaz ke Phool-like films that played with form? Would the New Wave or “parallel” movement then have come to Hindi cinema earlier than the 1970s? If Geeta Dutt had survived and sustained a decades-long rivalry with Lata Mangeshkar, would we have developed a more wide-ranging notion of what a heroine’s singing voice might be like? What if Bimal Roy had not arrived in Bombay in 1950 with his team (including Hrishikesh Mukherjee and Nabendu Ghosh)? How would that have impacted the social-message film and the later Middle Cinema? Or going a few decades back, what if Prithviraj Kapoor had listened to his father and stayed away from films altogether?

Yes, I know: given the neglect of – or even lack of awareness of – old cinema, it’s unlikely that enough viewers will be interested enough in such material to justify the production of an elaborate series. And there are other problems. When a film is clearly about (as opposed to “loosely based on”) a real-life story, and uses actual names, there will always be the question: how much dramatization amounts to crossing a line?

Yes, I know: given the neglect of – or even lack of awareness of – old cinema, it’s unlikely that enough viewers will be interested enough in such material to justify the production of an elaborate series. And there are other problems. When a film is clearly about (as opposed to “loosely based on”) a real-life story, and uses actual names, there will always be the question: how much dramatization amounts to crossing a line?

I was thinking about this while watching “Paterfamilias”, an outstanding episode of The Crown, about the boarding-school childhoods, 25 years apart, of two still-living royals – Prince Philip and his son Prince Charles. Beautifully written, structured, shot and performed, the episode combines grandeur with intimacy in a way that recalls the similar paralleling of the lives of a father and son in The Godfather Part II. Yet it has invited strong criticism for a scene (one that is central to the episode’s thematic concerns) that exaggerates a historical detail involving Philip’s own father.

In the Indian context, given how much we love using our “hurt sentiments” to get films banned and books pulped, it goes without saying that a show about the private lives and artistic compromises of real-life icons would – if it hasn’t already been sterilized at the production stage – face trouble. But we excitable fans can still dream – they did once call it the dream factory, after all – and make wishlists for the years ahead.

------------------------------

[Related posts: on RK Narayan’s essay about the Guide film; a preview of Sacred Games the TV series]

-----------------------

Most film buffs agree that the well-made long-form series (including web shows where a season’s worth of episodes might be released at one go) has outshone cinema in many ways. I’m a relative newbie to this world, but after having watched only a few such shows – The Crown and Mindhunter among them – the medium’s strengths are obvious: complex, carefully planned narrative arcs (writers often schematize a story so that a later episode makes you view a much earlier one in a new, more poignant light), the versatile and often contrapuntal use of music (Mindhunter’s first season ends by using the Led Zeppelin classic “In the Light” in ways that defy all our soundtrack instincts – yet it is brilliant), the occasional experimenting with episodes that work as self-contained mini-films.

Little wonder then that for Indian cineastes and book lovers, two of the most keenly anticipated events of this year are the Netflix adaptation of Vikram Chandra’s cops-and-gangsters novel Sacred Games – this series brings together such heavyweights as Anurag Kashyap, Vikramaditya Motwane, Saif Ali Khan and Nawazuddin Siddiqui – and the eight-part BBC series of another literary door-stopper, Vikram Seth’s A Suitable Boy. These sprawling novels deserve such a format.

What other Indian narratives could make for great TV or online shows? There are obvious stories in our literature, from ancient epics (and their many contemporary retellings or perspective tellings) to modern novels with a big canvas. But speaking as a film-history nerd who recently encountered the show Feud (about the Bette Davis-Joan Crawford rivalry), my “to be developed in 2018” wishlist would include any well-dramatized story about the Hindi film industry of the 1940s and 1950s.

There is plenty of promising source material (though authenticity may be in question). Consider Dev Anand’s deliciously florid autobiography Romancing With Life , which often reads like a

screenplay complete with full-fledged conversations, and scenes such as the one where the young Dev meets his idol Ashok Kumar (who keeps blowing cigarette smoke into his face) or has a last, weepy rooftop tryst with forbidden love Suraiya. Or take Saadat Hasan Manto’s gossipy, irreverent accounts of stars and directors.

screenplay complete with full-fledged conversations, and scenes such as the one where the young Dev meets his idol Ashok Kumar (who keeps blowing cigarette smoke into his face) or has a last, weepy rooftop tryst with forbidden love Suraiya. Or take Saadat Hasan Manto’s gossipy, irreverent accounts of stars and directors.Many of our major films have also had riveting back-stories: I can just about picture a limited series about the making of Mughal-e-Azam or Mother India or Sholay. Or Guide! The comic possibilities in an episode about RK Narayan’s growing dismay as his quiet Malgudi-based story is turned into a glamorous, pan-India spectacle are practically endless – and much of the material for this is already laid out in a sardonic essay that Narayan wrote about the experience.

Speaking of which, there is rich material in the travails of writers who worked in Hindi cinema – including those who sometimes had to strike a balance between their highbrow impulses and the formulaic demands made on them. Rahi Masoom Raza’s novel Scene 75 – just translated into English by Poonam Saxena – provides a sharply entertaining look at such people on the fringes of an industry where even a prominent writer’s sudden death must not be allowed to interfere with the joviality of a premiere.

Of course, such real-life narratives can be laced with a bit of “what if”, as the critic David Thomson did in an essay titled “James Dean at 50”, imagining a middle-aged version of the Rebel Without a Cause star (in reality, Dean died in his twenties). Some speculative fiction along those lines: what if Guru Dutt had lived and gone on to make more Pyaasa and Kaagaz ke Phool-like films that played with form? Would the New Wave or “parallel” movement then have come to Hindi cinema earlier than the 1970s? If Geeta Dutt had survived and sustained a decades-long rivalry with Lata Mangeshkar, would we have developed a more wide-ranging notion of what a heroine’s singing voice might be like? What if Bimal Roy had not arrived in Bombay in 1950 with his team (including Hrishikesh Mukherjee and Nabendu Ghosh)? How would that have impacted the social-message film and the later Middle Cinema? Or going a few decades back, what if Prithviraj Kapoor had listened to his father and stayed away from films altogether?

Yes, I know: given the neglect of – or even lack of awareness of – old cinema, it’s unlikely that enough viewers will be interested enough in such material to justify the production of an elaborate series. And there are other problems. When a film is clearly about (as opposed to “loosely based on”) a real-life story, and uses actual names, there will always be the question: how much dramatization amounts to crossing a line?

Yes, I know: given the neglect of – or even lack of awareness of – old cinema, it’s unlikely that enough viewers will be interested enough in such material to justify the production of an elaborate series. And there are other problems. When a film is clearly about (as opposed to “loosely based on”) a real-life story, and uses actual names, there will always be the question: how much dramatization amounts to crossing a line? I was thinking about this while watching “Paterfamilias”, an outstanding episode of The Crown, about the boarding-school childhoods, 25 years apart, of two still-living royals – Prince Philip and his son Prince Charles. Beautifully written, structured, shot and performed, the episode combines grandeur with intimacy in a way that recalls the similar paralleling of the lives of a father and son in The Godfather Part II. Yet it has invited strong criticism for a scene (one that is central to the episode’s thematic concerns) that exaggerates a historical detail involving Philip’s own father.

In the Indian context, given how much we love using our “hurt sentiments” to get films banned and books pulped, it goes without saying that a show about the private lives and artistic compromises of real-life icons would – if it hasn’t already been sterilized at the production stage – face trouble. But we excitable fans can still dream – they did once call it the dream factory, after all – and make wishlists for the years ahead.

------------------------------

[Related posts: on RK Narayan’s essay about the Guide film; a preview of Sacred Games the TV series]

Published on January 05, 2018 22:10

December 29, 2017

Reinventing the reel: Newton, A Death in the Gunj, Anaarkali of Aarah (a yearend list of sorts)

[For Mint Lounge’s yearend issue, Uday Bhatia and I did a piece that linked some of the best Hindi films of 2017 with earlier works. Here are my three contributions to the package. Full piece here]

----------------------------------

Dance as self-expression in Anaarkali of Aarah, Teesri Kasam and Guide

Hindi cinema has usually represented the courtesan, tawaif or nautch girl (each term linked to the others but also carrying subtle shifts in meaning or implication) as women performing for men, subject to the Gaze. Which is one reason why the final scene of Anaarkali Of Aarah—where the titular character uses a dance performance to reclaim her own sexuality, break the Fourth Wall and confront the powerful man who has been harassing her—is so exhilarating. Here is a woman expressing self-worth in a space traditionally associated with male privilege.

performance to reclaim her own sexuality, break the Fourth Wall and confront the powerful man who has been harassing her—is so exhilarating. Here is a woman expressing self-worth in a space traditionally associated with male privilege.

This is also evocative of two of Waheeda Rehman’s best roles: as Rosie in Guide and as Hirabai in Teesri Kasam. There are scenes in both films where the male leads—played by two of our biggest stars, the late Dev Anand and Raj Kapoor, respectively—are cowed down by the passion and abandon with which the heroine flings herself into dance. In Teesri Kasam, the naïve Hiraman (Kapoor) idealizes Hirabai (Rehman) and is shaken when he learns that she has been performing in this “disreputable” field since childhood; in Guide, Raju (Anand) wants to heroically rescue Rosie from her shackles, but himself feels insecure and subservient when she moves into the performative realm.

These are not feminist films in the direct, self-conscious way that Anaarkali Of Aarah is (it would be ridiculous to expect this, given that they were made in the mid-1960s), but they are remarkably progressive in their own contexts. And much of this has to do with Rehman’s personality. When in full flight as actor and dancer, she could make everything else in a film swim around her. Watch her magnificent snake dance in Guide and then that last scene in Anaarkali again; though separated by more than 50 years, they are part of the same conversation.

Familial ghosts in A Death in the Gunj and Trikaal

There are many ways in which to talk about Konkana Sensharma’s excellent directorial debut A Death In The Gunj—among them being its examination of the little cruelties and hegemonies that an “unmanly” man may be subjected to, even by a world that thinks of itself as modern. Shutu, played by the mesmerizing Vikrant Massey, has predecessors in our cinema: the many young men, in films like Parichay or Alaap, who prioritized “soft” pursuits like art (mainly music) or love over the family business, causing patriarchal wrath to descend on them.

But A Death In The Gunj is also notable as an example of the ensemble family film. By this I don’t mean a multi-starrer about a large clan, but an intimate, chamber drama-like story where a group of people are together in a relatively small space for a short period, and many mini-tragedies and mini-comedies unfold simultaneously. In this sense, it is strongly reminiscent of Shyam Benegal’s Trikaal, another film about a number of individuals with idiosyncrasies, personal demons and complicated interrelationships, and, like A Death In The Gunj, set in an atypical, old-world location (a mansion in 1960 Goa). Both works are marked by soft indoor lighting that makes the night-time scenes ominous and claustrophobic: Cinematographer

In this sense, it is strongly reminiscent of Shyam Benegal’s Trikaal, another film about a number of individuals with idiosyncrasies, personal demons and complicated interrelationships, and, like A Death In The Gunj, set in an atypical, old-world location (a mansion in 1960 Goa). Both works are marked by soft indoor lighting that makes the night-time scenes ominous and claustrophobic: Cinematographer

Ashok Mehta made brilliant use of candle-light in Trikaal, while lanterns dominate Sensharma’s film.

Ashok Mehta made brilliant use of candle-light in Trikaal, while lanterns dominate Sensharma’s film.

Interestingly, both feature séances too—though in the newer film, what seems at first to be a supernatural interlude turns out to be another cruel joke played on Shutu; while in the older film, there really is some form of magic involving Kulbhushan Kharbanda marvellously chewing up the scenery. Which is not to say that A Death In The Gunj doesn’t have its own ghost — albeit a more melancholy one.

The perils of idealism in Newton and Satyakam

Amit Masurkar’s Newton—about an idealistic government clerk, a stickler for rules, sent for election duty in Naxal land—carries echoes of a nearly 50-year-old film with a similarly unbending hero: Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s Satyakam, about a young engineer, Satyapriya (Dharmendra), who refuses to compromise even if it imperils the people who are dependent on him.

In some ways, the differences are just as important. Newton has a dry sense of humour (a herd of goats obediently bleat “haiii” as if in response to the question, “Do you have voter IDs?”), while the stately 1969 film rarely permits itself a smile. But at the centre of both stories are two earnest men whose inflexible commitment to their principles is often a source of frustration to everyone around them.

In some ways, the differences are just as important. Newton has a dry sense of humour (a herd of goats obediently bleat “haiii” as if in response to the question, “Do you have voter IDs?”), while the stately 1969 film rarely permits itself a smile. But at the centre of both stories are two earnest men whose inflexible commitment to their principles is often a source of frustration to everyone around them.

And yet, here’s a modest proposal: Neither film is unequivocally supportive of its hero. This is more obvious in the newer film, because it is more multilayered at a surface level and allows for perspectives other than Newton’s—notably that of chief of security Aatma Singh (a terrific Pankaj Tripathi), who understands ground realities and the nature of realpolitik in a complicated country better than Newton does. Or the local girl who tells the clerk, with a quiet smile, “You live only a few hours away but you know nothing about us.”

And yet, here’s a modest proposal: Neither film is unequivocally supportive of its hero. This is more obvious in the newer film, because it is more multilayered at a surface level and allows for perspectives other than Newton’s—notably that of chief of security Aatma Singh (a terrific Pankaj Tripathi), who understands ground realities and the nature of realpolitik in a complicated country better than Newton does. Or the local girl who tells the clerk, with a quiet smile, “You live only a few hours away but you know nothing about us.”

However, Satyakam—on the face of it a more moralistic film—also has scenes where the protagonist has a mirror held up to him (in one case by a character who might otherwise have been stereotyped as a slimy opportunist). Though Mukherjee repeatedly claimed that it was his favourite work, his career is more noted for protagonists who have a much greater sense of fun than the dour Satyapriya—people like Anand and Gol Maal’s Ram Prasad, who contain multitudes and are more understanding of the chimerical sides of human nature.

Both films allow us to reflect that if the world were made up entirely—or even mostly—of Newtons and Satyapriyas, then yes, it would probably be a better, more ethical place; but it would also be much blander, more robotic, less human. A landscape of clockwork oranges.

[Related posts: Anaarkali of Aarah; Trikaal; Satyakam; Guide]

----------------------------------

Dance as self-expression in Anaarkali of Aarah, Teesri Kasam and Guide

Hindi cinema has usually represented the courtesan, tawaif or nautch girl (each term linked to the others but also carrying subtle shifts in meaning or implication) as women performing for men, subject to the Gaze. Which is one reason why the final scene of Anaarkali Of Aarah—where the titular character uses a dance

performance to reclaim her own sexuality, break the Fourth Wall and confront the powerful man who has been harassing her—is so exhilarating. Here is a woman expressing self-worth in a space traditionally associated with male privilege.

performance to reclaim her own sexuality, break the Fourth Wall and confront the powerful man who has been harassing her—is so exhilarating. Here is a woman expressing self-worth in a space traditionally associated with male privilege.This is also evocative of two of Waheeda Rehman’s best roles: as Rosie in Guide and as Hirabai in Teesri Kasam. There are scenes in both films where the male leads—played by two of our biggest stars, the late Dev Anand and Raj Kapoor, respectively—are cowed down by the passion and abandon with which the heroine flings herself into dance. In Teesri Kasam, the naïve Hiraman (Kapoor) idealizes Hirabai (Rehman) and is shaken when he learns that she has been performing in this “disreputable” field since childhood; in Guide, Raju (Anand) wants to heroically rescue Rosie from her shackles, but himself feels insecure and subservient when she moves into the performative realm.

These are not feminist films in the direct, self-conscious way that Anaarkali Of Aarah is (it would be ridiculous to expect this, given that they were made in the mid-1960s), but they are remarkably progressive in their own contexts. And much of this has to do with Rehman’s personality. When in full flight as actor and dancer, she could make everything else in a film swim around her. Watch her magnificent snake dance in Guide and then that last scene in Anaarkali again; though separated by more than 50 years, they are part of the same conversation.

Familial ghosts in A Death in the Gunj and Trikaal

There are many ways in which to talk about Konkana Sensharma’s excellent directorial debut A Death In The Gunj—among them being its examination of the little cruelties and hegemonies that an “unmanly” man may be subjected to, even by a world that thinks of itself as modern. Shutu, played by the mesmerizing Vikrant Massey, has predecessors in our cinema: the many young men, in films like Parichay or Alaap, who prioritized “soft” pursuits like art (mainly music) or love over the family business, causing patriarchal wrath to descend on them.

But A Death In The Gunj is also notable as an example of the ensemble family film. By this I don’t mean a multi-starrer about a large clan, but an intimate, chamber drama-like story where a group of people are together in a relatively small space for a short period, and many mini-tragedies and mini-comedies unfold simultaneously.

In this sense, it is strongly reminiscent of Shyam Benegal’s Trikaal, another film about a number of individuals with idiosyncrasies, personal demons and complicated interrelationships, and, like A Death In The Gunj, set in an atypical, old-world location (a mansion in 1960 Goa). Both works are marked by soft indoor lighting that makes the night-time scenes ominous and claustrophobic: Cinematographer

In this sense, it is strongly reminiscent of Shyam Benegal’s Trikaal, another film about a number of individuals with idiosyncrasies, personal demons and complicated interrelationships, and, like A Death In The Gunj, set in an atypical, old-world location (a mansion in 1960 Goa). Both works are marked by soft indoor lighting that makes the night-time scenes ominous and claustrophobic: Cinematographer

Ashok Mehta made brilliant use of candle-light in Trikaal, while lanterns dominate Sensharma’s film.

Ashok Mehta made brilliant use of candle-light in Trikaal, while lanterns dominate Sensharma’s film.Interestingly, both feature séances too—though in the newer film, what seems at first to be a supernatural interlude turns out to be another cruel joke played on Shutu; while in the older film, there really is some form of magic involving Kulbhushan Kharbanda marvellously chewing up the scenery. Which is not to say that A Death In The Gunj doesn’t have its own ghost — albeit a more melancholy one.

The perils of idealism in Newton and Satyakam

Amit Masurkar’s Newton—about an idealistic government clerk, a stickler for rules, sent for election duty in Naxal land—carries echoes of a nearly 50-year-old film with a similarly unbending hero: Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s Satyakam, about a young engineer, Satyapriya (Dharmendra), who refuses to compromise even if it imperils the people who are dependent on him.

In some ways, the differences are just as important. Newton has a dry sense of humour (a herd of goats obediently bleat “haiii” as if in response to the question, “Do you have voter IDs?”), while the stately 1969 film rarely permits itself a smile. But at the centre of both stories are two earnest men whose inflexible commitment to their principles is often a source of frustration to everyone around them.

In some ways, the differences are just as important. Newton has a dry sense of humour (a herd of goats obediently bleat “haiii” as if in response to the question, “Do you have voter IDs?”), while the stately 1969 film rarely permits itself a smile. But at the centre of both stories are two earnest men whose inflexible commitment to their principles is often a source of frustration to everyone around them.  And yet, here’s a modest proposal: Neither film is unequivocally supportive of its hero. This is more obvious in the newer film, because it is more multilayered at a surface level and allows for perspectives other than Newton’s—notably that of chief of security Aatma Singh (a terrific Pankaj Tripathi), who understands ground realities and the nature of realpolitik in a complicated country better than Newton does. Or the local girl who tells the clerk, with a quiet smile, “You live only a few hours away but you know nothing about us.”

And yet, here’s a modest proposal: Neither film is unequivocally supportive of its hero. This is more obvious in the newer film, because it is more multilayered at a surface level and allows for perspectives other than Newton’s—notably that of chief of security Aatma Singh (a terrific Pankaj Tripathi), who understands ground realities and the nature of realpolitik in a complicated country better than Newton does. Or the local girl who tells the clerk, with a quiet smile, “You live only a few hours away but you know nothing about us.”However, Satyakam—on the face of it a more moralistic film—also has scenes where the protagonist has a mirror held up to him (in one case by a character who might otherwise have been stereotyped as a slimy opportunist). Though Mukherjee repeatedly claimed that it was his favourite work, his career is more noted for protagonists who have a much greater sense of fun than the dour Satyapriya—people like Anand and Gol Maal’s Ram Prasad, who contain multitudes and are more understanding of the chimerical sides of human nature.

Both films allow us to reflect that if the world were made up entirely—or even mostly—of Newtons and Satyapriyas, then yes, it would probably be a better, more ethical place; but it would also be much blander, more robotic, less human. A landscape of clockwork oranges.

[Related posts: Anaarkali of Aarah; Trikaal; Satyakam; Guide]

Published on December 29, 2017 08:09

December 24, 2017

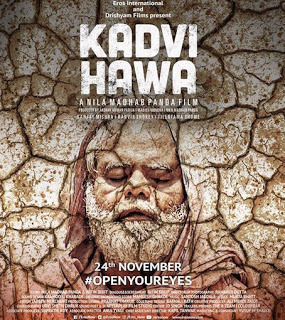

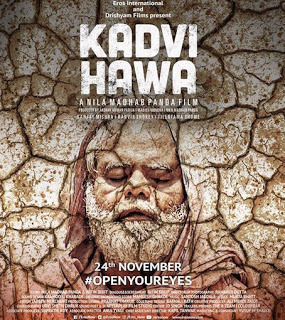

On Kadvi Hawa, and our obsession with takeaways

[did this for Mint Lounge]

To my mind, Nila Madhab Panda is one of our more interesting contemporary directors, even though his output is uneven. Panda’s films tend to be sombre, languidly paced and deal with important social issues, which are all qualities that we associate with heavy-handed message-mongering – and yet his better work finds a way to approach a subject tangentially and to bring to it the ambiguous, shifting texture of a dark fable. This makes it very different in effect from, say, Madhur Bhandarkar’s forays into social commentary, which are glossier, more accessible, and more didactic.

Panda’s Jalpari, for instance, links female infanticide with drought – two symptoms of a barren society – through a mostly realist narrative that alludes to mermaids, witchcraft and a mysterious swamp that everyone stays away from. In I am Kalam, a dhaba bordering a desert land is like a magical space of transition, a portal to a new destiny; a scary close-up of a villain burning the young protagonist’s precious papers might remind you of the witch at her oven in Hansel and Gretel.

And in his latest, Kadvi Hawa, a debt-collector whose appearances herald farmer suicides is feared as a Yam-doot or a messenger of death – though he is really just a morose man with problems of his own, clattering about on a little scooter and carrying files instead of a long noose.

Kadvi Hawa is not an easy film. It is slow to the point of meandering, and announces its intentions to be this way right from the long, poetic opening sequence where an old man taps his way through a beautiful but parched rural landscape until he finally reaches a rundown bank and is then made to wait for hours. But if you have the patience for it and if you’re in the right mood, it is very rewarding, with two wonderful performances by Sanjay Mishra (as the old man, Hedu, who turns out to be both blind and a “seer” – in the sense of clairvoyant) and Ranvir Shorey (as Gunu babu, the callous collector who reveals new sides as the story moves forward). At its heart, the film is a character study of these two people who shoulder different burdens (to put it very simply, one is haunted by a lack of water, the other by an excess of it) and are driven by their desperation towards a moral abyss.

Kadvi Hawa is not an easy film. It is slow to the point of meandering, and announces its intentions to be this way right from the long, poetic opening sequence where an old man taps his way through a beautiful but parched rural landscape until he finally reaches a rundown bank and is then made to wait for hours. But if you have the patience for it and if you’re in the right mood, it is very rewarding, with two wonderful performances by Sanjay Mishra (as the old man, Hedu, who turns out to be both blind and a “seer” – in the sense of clairvoyant) and Ranvir Shorey (as Gunu babu, the callous collector who reveals new sides as the story moves forward). At its heart, the film is a character study of these two people who shoulder different burdens (to put it very simply, one is haunted by a lack of water, the other by an excess of it) and are driven by their desperation towards a moral abyss.

The one scene that seemed forced to me came after this main narrative has ended: before the closing credits, we get text with information about farmer suicides in India as well as the problem of extreme climates around the world caused by human irresponsibility. Here was the moment where – instead of simply absorbing the experience of having watched a quiet, superbly acted slice-of-life story – we could congratulate ourselves on having paid for tickets for a film about Important Things.

I’m not saying Kadvi Hawa isn’t about those big issues (though the way it links them is a bit random and overdone, like a tourist at a buffet breakfast piling bacon and idlis on a single plate). But for most of its running time, “Suggest, don’t tell” is the chief mode. The social and ecological conditions that have caused the characters’ problems aren’t presented to us explicitly – we are allowed to conjecture their importance to the Hedu-Gunu story. Information accumulates on the fringes; people speak in muttered half sentences; there are effective little moments such as the one where a girl is called out from her classroom, the teacher casts her a quick concerned look, and we only gradually realise that her father has killed himself.

Information accumulates on the fringes; people speak in muttered half sentences; there are effective little moments such as the one where a girl is called out from her classroom, the teacher casts her a quick concerned look, and we only gradually realise that her father has killed himself.

Given these strengths, that closing information feels like an attempt to inject gravitas and respectability into a film that already had those things. We are being spoon-fed.

Some weeks ago, at a literature festival, I was involved in a discussion about the popularity of “takeaways”, or easy-to-digest ways of understanding creative works. This is based on the expectation that a casual reader (or viewer) should be able to say “Ah! This book/film was about *insert preferred theme or idea*” As if that was the only thing it was about, and as if anything can or should be reduced to a single defining message.

Such simplifications naturally occur when people think of books and films in purely utilitarian terms, focusing on the final takeaway rather than the fullness of the experience. Pandering to such a view, a film version of a famous literary work might end with a scroll saying “Research shows that killing an authority figure produces crippling guilt in 76 percent of people, and causes the breakdown of marriage and the onset of delusions in 17 percent. In many countries, including Scotland, these figures have been increasing since 1372 AD.” Which is useful information, no doubt, but it doesn’t tell us much about what makes Macbeth a good play or Maqbool a good film.

-----------------------------

[Here's a post about Panda's Jalpari: The Desert Mermaid]

To my mind, Nila Madhab Panda is one of our more interesting contemporary directors, even though his output is uneven. Panda’s films tend to be sombre, languidly paced and deal with important social issues, which are all qualities that we associate with heavy-handed message-mongering – and yet his better work finds a way to approach a subject tangentially and to bring to it the ambiguous, shifting texture of a dark fable. This makes it very different in effect from, say, Madhur Bhandarkar’s forays into social commentary, which are glossier, more accessible, and more didactic.

Panda’s Jalpari, for instance, links female infanticide with drought – two symptoms of a barren society – through a mostly realist narrative that alludes to mermaids, witchcraft and a mysterious swamp that everyone stays away from. In I am Kalam, a dhaba bordering a desert land is like a magical space of transition, a portal to a new destiny; a scary close-up of a villain burning the young protagonist’s precious papers might remind you of the witch at her oven in Hansel and Gretel.

And in his latest, Kadvi Hawa, a debt-collector whose appearances herald farmer suicides is feared as a Yam-doot or a messenger of death – though he is really just a morose man with problems of his own, clattering about on a little scooter and carrying files instead of a long noose.

Kadvi Hawa is not an easy film. It is slow to the point of meandering, and announces its intentions to be this way right from the long, poetic opening sequence where an old man taps his way through a beautiful but parched rural landscape until he finally reaches a rundown bank and is then made to wait for hours. But if you have the patience for it and if you’re in the right mood, it is very rewarding, with two wonderful performances by Sanjay Mishra (as the old man, Hedu, who turns out to be both blind and a “seer” – in the sense of clairvoyant) and Ranvir Shorey (as Gunu babu, the callous collector who reveals new sides as the story moves forward). At its heart, the film is a character study of these two people who shoulder different burdens (to put it very simply, one is haunted by a lack of water, the other by an excess of it) and are driven by their desperation towards a moral abyss.

Kadvi Hawa is not an easy film. It is slow to the point of meandering, and announces its intentions to be this way right from the long, poetic opening sequence where an old man taps his way through a beautiful but parched rural landscape until he finally reaches a rundown bank and is then made to wait for hours. But if you have the patience for it and if you’re in the right mood, it is very rewarding, with two wonderful performances by Sanjay Mishra (as the old man, Hedu, who turns out to be both blind and a “seer” – in the sense of clairvoyant) and Ranvir Shorey (as Gunu babu, the callous collector who reveals new sides as the story moves forward). At its heart, the film is a character study of these two people who shoulder different burdens (to put it very simply, one is haunted by a lack of water, the other by an excess of it) and are driven by their desperation towards a moral abyss. The one scene that seemed forced to me came after this main narrative has ended: before the closing credits, we get text with information about farmer suicides in India as well as the problem of extreme climates around the world caused by human irresponsibility. Here was the moment where – instead of simply absorbing the experience of having watched a quiet, superbly acted slice-of-life story – we could congratulate ourselves on having paid for tickets for a film about Important Things.

I’m not saying Kadvi Hawa isn’t about those big issues (though the way it links them is a bit random and overdone, like a tourist at a buffet breakfast piling bacon and idlis on a single plate). But for most of its running time, “Suggest, don’t tell” is the chief mode. The social and ecological conditions that have caused the characters’ problems aren’t presented to us explicitly – we are allowed to conjecture their importance to the Hedu-Gunu story.

Information accumulates on the fringes; people speak in muttered half sentences; there are effective little moments such as the one where a girl is called out from her classroom, the teacher casts her a quick concerned look, and we only gradually realise that her father has killed himself.

Information accumulates on the fringes; people speak in muttered half sentences; there are effective little moments such as the one where a girl is called out from her classroom, the teacher casts her a quick concerned look, and we only gradually realise that her father has killed himself. Given these strengths, that closing information feels like an attempt to inject gravitas and respectability into a film that already had those things. We are being spoon-fed.