Alan Jacobs's Blog, page 167

June 23, 2021

Little Platoons

Matt Feeney’s Little Platoons: A Defense of Family in a Competitive Age is a fascinating and provocative book that, in my judgment anyway, cries out for a sequel.

Before I go any further I should say that I’ve known Matt for years – we used to be co-conspirators at The American Scene – and we’ve corresponded occasionally since then, though not recently.

If there is any one idea that conservatives are thought to share, it’s the belief that a healthy society needs healthy mediating institutions. This is the burden of Yuval Levin’s recent book A Time to Build, and Yuval (also a friend) makes this argument about as well as it can be made. We do not flourish either as individuals or as a society when there is nothing to mediate between the atomized individual and the massive power of the modern nation-state. That’s why it’s always, though especially now, “a time to build” those mediating institutions that collectively are known as “civil society.”

The really brilliant thing about Matt’s book — written by someone who, like me, possesses a conservative disposition but might not be issued a card by the people who authorize “card-carrying conservatives” — is its claim that in some areas of contemporary American life the mediating institutions are not too weak but rather too strong. And what he demonstrates with great acuity is the consistency with which those institutions, from youth soccer organizations to college admissions committees, have conscripted the “little platoon” of the family to serve their needs — indeed, to get families to compete with one another to serve those institutions’ needs:

What happens, though, when citizens direct their suspicion not at a coercive government but at their peers, with whom they find or feel themselves, as parents and families, in competition? I join a chorus of scholars and writers in observing that such a competitive mood abides among parents today. Less noticed is how such competition creates new forms of subservience and conformity among families. In this environment, the intermediate bodies of civil society, cornerstone of the conservative theory of republican liberty, sometimes become demanding bosses, taskmasters, and gatekeepers in the enterprise of winning advantage for our children in a system of zero-sum competition.

As a result,

Under these conditions, the anxious and competitive citizen-parent looks to certain “voluntary associations,” certain institutions within “civil society,” not as bulwarks against coercive government but as ways to gain advantage over other families, exclusive paths to better futures. From boutique preschools to competitive sports clubs to selective colleges and universities, desirable institutions become bidding objects for future-worried and status-conscious families.

Thus, “the era of intensive parenting is defined by the rise of a sort of hybrid entity, an institutional cyborg that is part organization and part family.”

Matt is not by any means opposed to these mediating institutions as such — there’s a wonderful section on how he learned, through walking his kids to school every day and then hanging out for a while with teachers and other parents, how a school really can be the locus of genuine community — but looks with a gimlet eye, a Foucauldian gimlet eye, on the ways that, right now, in this country, a few such institutions form, sustain and disseminate their power over families.

He’s scathing about college admissions, especially the turn towards “holistic” admissions processes which serve to transform mid-level administrators into eager shapers of souls. He mentions a Vice Provost at Emory who laments the imperfection of his knowledge of the inner lives of applicants, and continues:

If you recall that, twenty or thirty years ago, admissions departments weren’t even mentioning authenticity, were not treating the therapeutic search for true voices and true selves as the goal of their investigations, and if you devote a moment’s thought to the absurdity of this search, you will be tempted to laugh at Vice Provost Latting’s hysterical protest against imperfect knowledge. But, laughable as this and other admissions testimony is, on its merits, I would like to present a good reason not to laugh. Setting up a yearslong, quasi-therapeutic process in which you goad young people to lay bare their vulnerable selves to you, when this process is actually a high-value transaction in which you use your massive leverage to mold those selves to your liking, is actually a terrible thing to do.

Yes, it is. And I am glad to hear someone say it so bluntly.

In his conclusion, Matt admits his reluctance to give advice to parents in such a coercive and panoptic environment, and that’s perfectly understandable. In any case, the primary function of the the primary purpose of the book is diagnostic: he wants to show us the specific ways in which these various mediating institutions co-opt families, and even in some cases make the families hosts to which they are the parasites. I don’t think that the book would have held together as well if it had tried to include parenting advice in the midst of everything else. But it is obvious that Matt has thought quite a lot about what it means to be a responsible parent in our time – he has a great riff on why he’s okay with the fact that his oldest daughter is the only person in her class who doesn’t have a smartphone – and I would really like to hear more from him about how he conceives of the positive responsibilities of being a parent, the dispositions and actions which strengthen that little platoon. I don’t think he needs to do this in a pop-psychology self-help way; Matt is by training a philosopher and I think philosophical reflection on this topic, so essential to human flourishing, would be welcome from him.

But the book provides a great service simply by teasing out the ways in which families are not served by but rather are made to serve these parasitic institutions — and the ways in which we are manipulated to do so ever more intensely by our felt need to compete with other families. As we are always told, the first step is acknowledging that you have a problem.

June 22, 2021

Barney Ronay:

Chekhov came up with the idea of the shotgu...

Chekhov came up with the idea of the shotgun above the mantelpiece. If there’s a gun on the wall in Act 1 of your drama, someone had better be firing it by Act 2. By the same token if you have an abundance of attacking talent – dribblers, speed-merchants, velvet-touch princelings – at some point you really do need to encourage them to show it on the pitch.

For now Southgate seems to have rejected this dramatic rule in favour of something more diffuse. We appreciate and welcome guns as a basic principle. We have a wealth of promising guns in the pathway. We will, in due course, be reviewing their use as part of a wider process. Now. Shall we talk about right-backs for a bit?

Gareth Southgate indeed has “an abundance of attacking talent” at his disposal, and clearly considers this his cross to bear. What he wants is an entire team of Jordan Hendersons.

UPDATE AFTER THE MATCH: If Southgate hadn’t acted decisively to get his three most creative and dangerous players (Saka, Grealish, Sterling) off the pitch, England might have scored again. What a nightmare that would have been.

The players have mostly been very good, despite their manager’s desperate attempts to stifle them. I’m looking forward to the 8-1-1, with poor old Harry Kane lumbering along at the front of the line like one of the Walking Dead, that Southgate will deploy in the knockout round.

two poems in support of my recent posts

If we deny our happiness, resist our satisfaction,

we lessen the importance of their deprivation.

We must risk delight. We can do without pleasure,

but not delight. Not enjoyment. We must have

the stubbornness to accept our gladness in the ruthless

furnace of this world. To make injustice the only

measure of our attention is to praise the Devil.

— from “A Brief for the Defense” by Jack Gilbert

Love the quick profit, the annual raise,

vacation with pay. Want more

of everything ready-made. Be afraid

to know your neighbors and to die.

And you will have a window in your head.

Not even your future will be a mystery

any more. Your mind will be punched in a card

and shut away in a little drawer.

When they want you to buy something

they will call you. When they want you

to die for profit they will let you know.

So, friends, every day do something

that won’t compute. Love the Lord.

Love the world. Work for nothing.

Take all that you have and be poor.

Love someone who does not deserve it.

— from “Manifesto: The Mad Farmer Liberation Front” by Wendell Berry

June 21, 2021

A tiny pendant to the previous post: One of the ways I tr...

A tiny pendant to the previous post: One of the ways I try to maintain the very possibility of thinking of this blog in gift-economy terms is by avoiding all analytics. I don’t know how many people read this blog — I’d guess that regular readers are probably in the high two figures — ; I don’t know which posts get more attention and which get less. (Not posting to Twitter helps here also.) My ignorance protects me from playing to the crowd. Since I crave attention as much as the next guy, preserving my ignorance is an important discipline for me.

I also want to write at some point about how this blog can even potentially participate in the gift economy only because I do other things that participate in the market economy.

managers and givers

I have written frequently on this blog about what I call metaphysical capitalism, and that orientation to the world takes several forms:

Understanding human relationships in purely contractual terms: e.g., consent becomes the only criterion of sexual ethics.Believing that my happiness can be purchased in the marketplace, and further that a just society purchases my happiness for me (e.g. by paying for my sex-reassignment surgery or my MFA). Conceiving of conflict as a matter to be resolved by appealing to The Authorities: as someone once said (extended searching hasn’t recovered the source), a disturbingly large number of people treat almost every conflict, at work or at play or on social media, as an excuse to Convince Management to Take Their Side — to take their side by getting some offending person fired, or banned from YouTube, silenced, excluded. This view is capitalist in a distinctively modern sense, because it assumes massive corporate bureaucracy as an immutable given, like what we used to call “a force of nature” before we decided that nature is not given but rather plastic and moldable according to our will.Each of these forms of metaphysical capitalism is a way of giving up — giving up on meaningful structural change to our social order, giving up on imagining an alternative to technocracy, giving up on thinking of my self as something other than a commodity (even if it’s a commodity I claim to own). It’s agreeing — probably unconsciously, unthinkingly — not just to live under the corporate constitution but to see that constitution as the only Power enabling our flourishing.

We typically don’t see it, but this is Lucifer as new management.

Lately I’ve been re-reading Lewis Hyde’s The Gift, which clearly describes the radical difference between the market economy and the gift economy, but struggles to articulate a way to escape the former and embrace the latter. The spread of the market economy into every area of life is exactly what I mean when I talk about metaphysical capitalism, and Hyde sees this spread arising from, made necessary by, bad faith: “Out of bad faith comes a longing for control, for the law and the police. Bad faith suspects that the gift will not come back, that things won’t work out, that there is a scarcity so great in the world that it will devour whatever gifts appear. In bad faith the circle is broken.”

Again and again in this book Hyde makes three points.

A gift is not a gift unless it circulates. Circulation requires more than two people. “The gift moves in a circle, and two people do not make much of a circle. Two points establish a line, but a circle lies in a plane and needs at least three points.”The one who wishes to engage in the gift economy must give without expectation of return — must give in the knowledge that those who receive it will only be able, or willing, to do so in the terms of the market economy. The recipient, that is, may simply keep the gift rather than passing it on, thus failing to maintain the necessary circulation.The implications of this argument are multiple. Here I just want to note one that Hyde acknowledges and one he does not. He sees the connection with a topic I have sometimes explored here and hope to explore further: anarchism. “There are many connections between anarchist theory and gift exchange as an economy – both assume that man is generous, or at least cooperative, ‘in nature’; both shun centralized power; both are best fitted to small groups and loose federations; both rely on contracts of the heart over codified contract, and so on…. Anarchism and gift exchange share the assumption that it is not when a part of the self is inhibited and restrained, but when a part of the self is given away, that community appears.”

The second implication is theological: This is my body, given for you. The death of Jesus Christ on the cross is offered, is graciously given — see John Barclay’s Paul and the Gift — to those who may not receive it at all, or who may receive it greedily, in hopes of keeping it as their own, their Precious, not forwarding the gift into circulation, not allowing community to appear. Again search is not helping, but I think it’s John Milbank who writes somewhere of “the tragic risk of kenosis,” the tragic risk of God’s self-emptying for people who neither deserve nor especially want that gift. (It would be seriously wrong to think that “He came unto his own, and his own received him not” is a statement only or even primarily about Israelites.)

One of the things I love most about the structure of the modern Eucharistic rite is the way it enables, and calls our attention to, this circulation of gifts. We begin with the Liturgy of the Word: we hear Scripture read and preached, we make our profession of faith, we confess our sins against God and our neighbor, we exchange the Peace with one another; and then, in gratitude for this our reconciliation, we bring our gifts to the altar. (“All things come of thee, O Lord, and of thine own have we given thee.”) But that just leads to the Liturgy of the Table, at which the ultimate Gift is celebrated and received: the Gift of the sacrifice of Jesus Christ. No matter what we try to give back, God always gives more, and more, and more. My cup runneth over. So those financial gifts we offered go out into a needy community, and we ourselves, at the end of the service, ask God to “Send us out into the world in peace, to love and serve You with gladness and singleness of heart.” It’s not a line, it’s a circle.

Well. These are high thoughts. But what I am trying to do is connect these theological and social ideas with certain quotidian practices — for instance, writing blog posts. There are two major reasons why I am writing about these matters on my blog. One is that the blog format allows for ideas to be developed tentatively, to be returned to, to be revised and expanded. But the other reason is that blogging at its best can be a form of participation in a gift economy: I’m not asking you to pay anything for what I write here, and if you find that it has any value, you may easily share the URLs with others. It ain’t much, but it’s what I got. And who knows, maybe circulation will add to its currently quite limited value.

two constitutions

Today Americans live under two constitutions: the political constitution and the corporate constitution. The political constitution is functioning reasonably well. The corporate constitution, by comparison, is a lawless realm of out-of-control tyranny.

The American political constitution’s system of checks and balances is not perfect, but it has been vindicated during the four tempestuous years of the Trump presidency. Donald Trump lost power in a free and fair election. Numerous courts and state officials and his own vice president have rejected his claims that the election was illegally stolen. He has now been impeached a second time, and his violent supporters who stormed the Capitol on Jan. 6 are being arrested and those who committed crimes against persons and property will receive due process under the law.

But if our political constitution is that of a flawed but functioning democracy, the same cannot be said of our corporate constitution. In our corporate constitution, giant oligopolistic firms that are essential to commerce, communications, and finance operate in many cases without any regulations other than those which they themselves make.

June 20, 2021

giving breath back to the dead

History in general is easily manipulable, and can always be applied for the pursuit of present goals, whatever these may be. It has long seemed to me that one of the more noble uses of history is to help us convince ourselves of the contingency of our present categories and practices. And it is for this reason, principally, that I am not satisfied with seeing history-of-philosophy curricula and conferences “diversified” as if seventeenth-century Europe were itself subject to our current DEI directives.

One particularly undesirable consequence of such use of history for the present is that it invites and encourages your political opponents likewise to marshall it for their own present ends. And in this way history becomes just another forked node of presentist Discourse — the foreign and unassimilable lives of all of those who actually lived in 1619 or 1776 are covered over. But history, when done most rigorously and imaginatively, gives breath back to the dead, and honors them in their humanity, not least by acknowledging and respecting the things they cared about, rather than imposing our own fleeting cares on them. Eventually, moreover, a thorough and comprehensive survey of the many expressions of otherness of which human cultures are capable in turn enables us, to speak with Seamus Heaney in his elegant translation of Beowulf, to “assay the hoard”: that is, to take stock of the full range of the human, and to begin to discern the commonalities behind the differences.

Anyone who happens to know what my most recent book was about will not be surprised at how vigorously I nod my head at this.

Attention! (a summary)

I obviously write about a good many things, but over the last decade my work has been largely devoted to a single overarching theme: what we attend to and what we fail to attend to. This started with the work on my old Text Patterns blog that fed into my 2011 book The Pleasures of Reading in an Age of Distraction, and since then I have pursued the various connected issues and problems down several paths. My set of Theses for Disputation, “Attending to Technology,” is my most explicit articulation of these concerns, but even when I didn’t seem to be thinking about these things I really was. Even my biography of the Book of Common Prayer was an attempt to understand the prayer book as an instrument for the focusing of the attention of wayward Christians on that to which they should primarily attend. As the BCP almost says, “We have attended to those things we should not have attended to, and we have not attended to those things which we should have attended to, and there is no health in us.” The relevance of these questions to How to Think will be obvious to anyone who has read it, but I could say the same about the two books that I published since then, The Year of Our Lord 1943 and Breaking Bread with the Dead. In each case I am concerned with the forces in our culture that inhibit enriching attentiveness, that enforce enervating distraction, that direct our minds always towards the frivolous or the malicious. (This is of course why I despise Twitter so intensely.)

The Invitation and Repair project might be understood as circling within this orbit of thought, but it’s also an attempt to go beyond my earlier, more purely diagnostic, thinking and to begin to understand how to embed concrete practices of life in concrete institutional structures. My most recent essay in The New Atlantis is likewise an attempt to forge a new and more constructive direction for thinking about and addressing our culture-wide attentional dysfunction. I have been interested in Chinese thought — looking into each of the Three Ways but especially Taoism — because the Chinese intellectual/spiritual traditions have always striven to identify and defeat the enemies of proper attention. Even something like the I Ching, which is commonly thought of as a straightforward manual of divination, is always said by its most eloquent and insightful proponents to be — as I have said the Book of Common Prayer is — a device for directing the attention. The I Ching doesn’t tell you what to do so much as tell you what you should be thinking about as you try to decide what to do – what your primary coordinates for judgment should be.

I’ve been intrigued by Chinese thought about these matters not because I think the Christian tradition, which I hold as my own, is deficient, though in fact I do believe that the Western church hasn’t been, well, sufficiently attentive to attention. Rather, I’m just trying to surprise myself. China Achebe used to say that he could write well about the traditional ways of the Igbo people because, while he observed them closely, they weren’t his ways, not when he was growing up. His Christian-convert father forbade him to consort with pagans, which just made pagans more interesting to him. He watched them more closely, and learned a lot from them, precisely because they were a step or two away from his ordinary beliefs and practices.

And that’s the goal, right? — not to think about attention, which is like thinking about your flashlight instead of using it to find your way in the dark, but rather to see more clearly — and, ultimately, direct your mind and heart and spirit towards what can nourish you. Indeed that is the goal; gut sometimes you might be forced to notice that your flashlight is running out of batteries, or isn’t very strong even at its best, so maybe you should try a different one, or see if you have any fresh batteries?

Such meta-reflection is dangerous, though. I find myself recalling Carlyle’s famous comment about talking with Coleridge: “He began anywhere: you put some question to him, made some suggestive observation: instead of answering this, or decidedly setting out towards answer of it, he would accumulate formidable apparatus, logical swim-bladders, transcendental life-preservers and other precautionary and vehiculatory gear, for setting out.” People who talk and write about “productivity” and even “attention” are like that, in a more mundane way. I don’t want to be. I don’t want to achieve ever-more-precise diagnoses of our attentional disorders; I don’t want to continue looking at the light, I want to look along it to see what it illuminates.

June 19, 2021

Thoughts on the Euros: 1

1. The Christian Eriksen story, of course, continues to loom large. It was a beautiful moment when his Inter teammate, Belgium striker Romelo Lukaku, ran to the camera after scoring against Russia to proclaim, “Chris, Chris, I love you!” And equally lovely when Belgium played Eriksen’s Denmark in the next match and the Danish fans, in gratitude, started chanting Lukaku’s name.

2. Harry Kane desperately needs some rest, and the smart thing would be for Gareth Southgate to sit him down, but I am quite confident that Gareth Southgate will not do the smart thing. England would be better at this point with Calvert-Lewin as striker, Grealish behind him as the number 10, and Sancho on the right wing, with Kane, Sterling, and either Phillips or Rice having a seat. And yeah, I know that Sterling scored England’s only goal so far, but overall he hasn’t been great, and I believe a front three of Calvert-Lewin, Foden, and Sancho would be very dangerous. (In the first two games England’s front three had a total of three shots on target.)

3. At the very end of France-Hungary, Endre Botka rugby-tackled Kimpembe in the box — ineptly, after which he fell to the ground in double humiliation, faking injury — and VAR said there was no foul. I am as sure as I can be that that happened because the game was played in a stadium full of delirious Hungarians. And after a year of players’ and coaches’ shouts echoing off empty seats, I’m kinda okay with that. The good thing about human error is that it’s human.

4. The two Ringer FC podcasts — Stadio and Wrighty’s House — are my very favorite podcasts, on any topic, and there was an especially moment in the most recent episode of Wrighty’s House, in which Ian Wright, Musa Okongwa, and Ryan Hunn were discussing the England-Scotland draw. Wrighty opined that, in Kieran Tierney and Andy Robertson, Scotland might have the best left side in world football. Sensing that the time had come for a Game of Thrones reference, Musa said “They’re the Iron Bank” — and then, to make it better, “the Iron Flank.” To which Ryan: “They’re the IRN-BRU Flank.” Too good.

5. Barney Ronay: “The Italian anthem repeats the line ‘We are ready to die’ four times in its second verse. At the Stadio Olimpico Chiellini sang it like it was something beautiful and impossibly tender.”

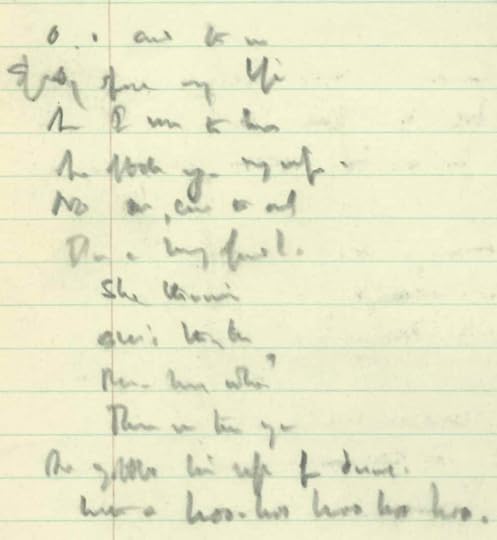

chirography

Dear reader, I’m sure you have a tough job, but reflect on this: You don’t have to try to decipher Auden’s handwriting.

Alan Jacobs's Blog

- Alan Jacobs's profile

- 534 followers