Alan Jacobs's Blog, page 163

July 28, 2021

beats me

Over the past ten days I’ve been thinking a good deal about my friend Michael Brendan Dougherty’s essay on responding to vaccine skeptics.

One key claim Michael makes is that “most vaccine skepticism, if by that we mean reluctance, is not based on conspiracy theorizing — it’s based on risk-benefit calculations.” I wonder if that’s true, and how we might know. All I can go by, in the absence of data, is my own experience, and certain elements of my experience with anti-vaxxers are absolutely uniform. Without exception, they tell me that

The covid pandemic may not be totally made-up, but its dangers are wildly and dramatically overstated by the mainstream media and liberal politicians;Covid is no worse than the flu;Masking doesn’t help;Vaccines don’t work;Vaccines are killing more people than covid has.That covers the substantive issues. But two other elements of my encounters with anti-vaxxers are uniform and, I think, significant:

They are openly and intensely angry;They declaim their beliefs like people reciting a creed, never — and I mean never — asking what my views are or even giving me a chance to state those views should I want to.Everything about their self-presentation militates against dialogue. So for me the question is not “How might I convince them?” but rather “What am I supposed to do if conversation between citizens is not even one of the options on the table?”

For the last forty years I have been interested in our common life in this country, in the ways we live together, and whenever we have experienced pronounced social tension I have had ideas for resolving or at least lessening those tensions. Those ideas have typically been uncommon ones, and I have rarely been under any illusions about the likelihood of their being adopted; but I have nonetheless believed in their likely efficacy. In our current situation I have no idea what to do. I have no tactical suggestions. None. I am totally and absolutely at a loss.

UPDATE: Relatedly, I think, this recent speech by Donald Trump:

No more windows in buildings because environment. I always did great with these buildings that the bigger the window, the better I did, the bigger those windows, I wanted floor to ceiling windows, but they say you can’t do that anymore. We don’t want any more windows. It’s going to be real hard to sell apartments, I think. We have a beautiful apartment, and for environmental reasons, we have not put windows in the building. Oh great. Well, that sounds good. These people are crazy. Whatever happened to cows, remember they were going to get rid of all the cows? They stopped that, people didn’t like that. Remember? You know why they were going to get rid of all the cows? People will be next. People will be in there.

Tens of millions of Americans hear this man speak and think: He will make America great again. In him we place our full trust. In response to this also, I am totally and absolutely at a loss. I don’t even know where to begin.

So I’ll just talk about other things. Snakes & Ladders will now return to its regular programming — and I’m resuming the newsletter next week!

separate … but equal?

I don’t want to see politicians get involved in what should and should not be taught. I would like to see parents speak to teachers and administrators when CRT is creating a bad classroom atmosphere. I would like to see teachers and administrators resist the urge to be defensive and resentful toward criticism of CRT.

But I worry that civil discourse around CRT is not going to happen. Instead, parents who most believe in civil discourse will simply pull their children out of public schools, rather than wade into the controversy. Teachers who are not “woke” will be treated as pariahs by other teachers and administrators. Public schools will end up serving the children of parents who are either very progressive or apathetic. There will emerge another school system, a separate but equal school system if you will, for children of parents who are conservatives or old-fashioned liberals.

two questions

After reading Elizabeth Bruenig’s remarkable article on a recent contretemps at Yale Law School — and after resisting the temptation to immediately take a shower and scrub myself clean — I found myself meditating on two questions:

Did the person Bruenig calls the Archivist believe that by devoting countless hours to investigating and prosecuting two of his classmates he was setting himself up for a high-powered, brilliant career?If so, was he right?July 27, 2021

citizens

I’ve just returned from Laity Lodge, where I had a glorious time with my dear friend Wesley Hill: talking about “praying with Jesus”; joyously embracing old friends — including our artist-in-residence Mia Carameros — but also making new friends; worshipping; listening; singing … what a memorable three days it was.

Among the many delights was getting to know Jon and Valerie Guerra, whose music greatly enlivened our time together. A real highlight was the Saturday evening concert, where they gave us a song I want to share with you all. There’s a lovely studio version, but maybe because I heard it live, I’m inclined to post this powerful solo performance by Jon, who gives us in song a prophetic word that I answer with an emphatic Amen:

July 18, 2021

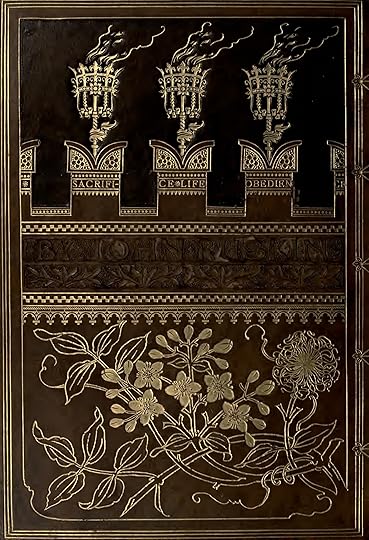

The Lamps

the Campanile of Giotto

John Ruskin, Tracery from the Campanile of Giotto in Florence; in The Seven Lamps of Architecture

tablets

When the iPad came out, more than a decade ago, I tweeted that I didn’t especially want an iPad but would really love an e-ink tablet, one on which I could read books and magazines and PDFs, and then make annotations on them. That didn’t seem very likely at the time, but now some of those devices have been produced, and I recently tried a couple of them.

The first device I bought was a reMarkable tablet, which features

excellent build qualityresponsive software, especially its handwriting recognitionvery good OCR of handwritingreliable syncingThe one problem I had with it turned out to be an insurmountable one. The device has no light of any kind, and the color of the screen is a disconcertingly dark gray; I found the contrast between black type and the gray screen so limited that I couldn’t read anything on the device without strain, except in the very brightest light. It was perfect outdoors, but usable indoors only at my desk, where I could point my desk lamp directly at the screen. So I had to return the reMarkable – with regrets, because it’s a cool device in other respects. I’m sure people with younger eyes than mine can enjoy it.

So after returning the reMarkable, I bought the Kobo Elipsa, which seemed more promising largely because it does have a so-called ComfortLight, which works well. However, that was the only good thing about the device. The build quality is mediocre at best – it feels flimsy – and the software is so unresponsive that I just couldn’t use it. I would tap something on the screen, the software keyboard would either not respond at all or respond only after a delay of several seconds. Writing with the included stylus was painful, so long was the delay between the movement of the stylus and the appearance of text on the screen.

If the reMarkable tablet featured the same lighting that the Elipsa does, I would’ve kept it and been very happy with it. It’s better-designed and better-built.

Finally: both companies make it hard to return their devices. You really have to hunt on the reMarkable website to find the page that tells you how to initiate a return, though once you do find that page the process is relatively straightforward. Kobo, though, doesn’t let you initiate a return without engaging a representative in chat or on the phone. And that’s a very slow process – they seem to be hoping that you will get tired of the delays, give up, and keep the device you don’t really want. When you obscure and complicate the process of returning devices, you make me disinclined to buy anything else from your company.

Shadow Kingdom

An amazing show, but too short. The best versions I’ve ever heard of “Queen Jane Approximately” and “Forever Young” — the latter a tearjerker.

July 17, 2021

Sant’Andrea al Quirinale

From the Met. Bernini’s Sant’Andrea al Quirinale in Rome is to me the most beautiful of churches. I am reading and thinking about Paradise Lost right now, and I have long thought that Paradise Lost is the Sant’Andrea al Quirinale of poems, and Sant’Andrea al Quirinale the Paradise Lost of churches. Maybe that analogy will make its way into my book.

July 16, 2021

asymmetrical charity

I mean my title to describe a peculiarity of the current Pope, who speaks often of the need for charity but seems to have little for people he thinks err — or anyway err in a certain direction. Thus his new Motu proprio on the use of the Latin Mass.

Francis is not at the moment completely forbidding the Latin Mass, but only because he finds slow asphyxiation more convenient than summary execution. As he says in his accompanying letter, he wants “to provide for the good of those who are rooted in the previous form of celebration” — but he also insists that these people “need to return in due time to the Roman Rite.” Note the forceful distinction between the Latin Mass and the Roman Rite — there can only be one Roman Rite; the Latin Mass is not a form of it but rather something … different. Indeed, those who adhere to the Latin Mass do not merely depart from the Roman Rite but effectively from the Church itself: they violate the Church’s unity, and “This unity I intend to re-establish throughout the Church of the Roman Rite.” Again: slow asphyxiation. He has not killed the Latin Mass but he intends it to die, and not in the distant future either.

Why? Francis says that “ever more plain in the words and attitudes of many is the close connection between the choice of celebrations according to the liturgical books prior to Vatican Council II and the rejection of the Church and her institutions in the name of what is called the ‘true Church.’” An enormous weight is being placed here on the word “many.” I do not doubt that the attitude describes is held by some. But, for what it’s worth, the Catholics I know who are drawn to the Latin Mass are not drawn to it because it sets them apart from other Catholics but because it binds them to the great cloud of witnesses who have preceded them in their faith. They do not despise their Church but rather love it; the Latin Mass for them is an excellent means of expressing and strengthening that love.

It is sad and strange to me that Francis can be so warm in his sympathy for those who openly reject his Church and its teachings, but so icy-cold, so corrosively skeptical, towards some of that Church’s most faithful sons and daughters. Sad, strange — and, I believe, profoundly unwise.

Alan Jacobs's Blog

- Alan Jacobs's profile

- 534 followers