Alan Jacobs's Blog, page 165

July 10, 2021

orbital obliquity

Planets which are tilted on their axis, like Earth, are more capable of evolving complex life. This finding will help scientists refine the search for more advanced life on exoplanets. […]

“The most interesting result came when we modeled ‘orbital obliquity’ — in other words how the planet tilts as it circles around its star,” explained Megan Barnett, a University of Chicago graduate student involved with the study. She continued, “Greater tilting increased photosynthetic oxygen production in the ocean in our model, in part by increasing the efficiency with which biological ingredients are recycled. The effect was similar to doubling the amount of nutrients that sustain life.”

“Orbital obliquity” is one of those scientific terms — like “persistence of vision” and “angle of repose” — that just cries out for metaphorical application.

All of the writers and thinkers I trust most are characterized by orbital obliquity. They are never quite perpendicular; they approach the world at a slight angle. As a result their minds evolve complex life.

July 9, 2021

revisiting

People keep asking, but I don’t have anything to add to the current brain-dead kerfuffle over “Critical Race Theory” that I haven’t already said.

The overwhelming majority of people who want to argue about CRT don’t know whether CRT is a man or a horse.

We teachers, caught between those who want to enforce a particular vision of social justice in our classrooms and those who want to banish that vision, are being told that everything that is not compulsory is forbidden.

Five years ago I published an essay arguing that the key to the renewal of the university is the rebuilding of bonds of trust, especially between teachers and students — but also among all the other stakeholders of higher education.

July 6, 2021

le mot juste

Asked for comment on Facebook Bulletin, Substack spokeswoman Lulu Cheng Meservey said, “The nice shiny rings from Sauron were also ‘free.’”

July 5, 2021

more on sexual difference

My friend Adam Roberts’s response to my Tiptree-and-difference post pushes me to clarify a few points. Or rather, to realize that I can’t yet clarify a few points and need to think further.

Imagine a sliding scale of sexual difference, ranging from, on the far left, … I don’t know, maybe having sex with a clone of yourself? — to, on the far right, “aliens in the shape of slime-blobs, or sentient piles of concrete blocks” (to quote Adam). Adam’s point is that the sexual xenomania of the man in “And I Awoke” is focused on aliens with a generally humanoid shape — aliens who, if you consider the possible morphologies of sentient life, manifest only minor differences from us.

So for any given person there will be a Point of Maximal Allurement — a point at which likeness and difference are balanced in such a way as to maximize desire. Tiptree suggests that if we humans ever do encounter aliens, that slider will, for many people, move to the right. New differences lead to new allurements. The question Adam asks is: Will it really happen that way? Is there, as Tiptree seems to think, a latent human xenophila just waiting for its chance to become manifest? (Adam has his doubts.)

But as I think about this I realize that Tiptree only occasionally suggests that such xenophilia is human — in the stories it is typically, rather, male. (The only exception I can think of is the unnamed, silent wife of the man in “As I Awoke,” and the strong suggestion is that her attraction to aliens is masochistic. The narrator’s sister in “A Momentary Taste of Being” is drawn to another world, another way of being, in a way that seems, to me anyway, unrelated to sexual desire.) And many of Tiptree’s stories represent male desire as a manifestation of male dominance: a man’s libido simply is the libido dominandi.

And that in turn makes me realize that I have not clearly defined allurement. Desire for intimacy ≠ desire for pleasure ≠ desire for conquest. And even if for men the third of those always displaces the other two, that doesn’t really answer the notorious Freudian question: “What do women want?” Tiptree’s stories — that is to say, stories written by a woman under a man’s name and almost always from the perspective of a male character — tell us a lot about what men want. But what do the women in “Houston, Houston, Do You Read?” want? In “The Women Men Don’t See,” what does Ruth want when she asks the aliens to take her away? She doesn’t say. Tiptree leaves such matters to the contemplation of the reader.

But did Alice B. Sheldon think she knew? She herself was twice married to men, but once said, “I like some men a lot, but from the start, before I knew anything, it was always girls and women who lit me up.” One could draw any number of conclusions about how her own patterns of desire shaped her fiction, and about why she does so much more to represent male desire than female, but it’s impossible to be confident that any of them are right.

July 4, 2021

difference

Lately I’ve been re-reading the stories that Alice B. Sheldon wrote under the name James Tiptree, Jr. and it occurs to me that almost all of them are meditations on the same theme: The way genuine difference, especially but not only sexual difference, simultaneously alienates and allures. Now, I should also add that the Tiptree stories seem unable to imagine this dialectic settling into a healthy tension; almost invariably the alienation and the allurement alike take pathological forms.

In “And I Awoke and Found Me Here on the Cold Hill’s Side” we meet a man and, eventually, his wife who are in the grip of a kind of sexual xenomania, obsessively lusting for aliens of various species in a way that the man perceives as pathological but inevitable. Sometimes the man sees in the aliens a kind of beauty, and traits that present in exaggerated form what he finds desirable in human women, but essentially it is the very alienness that obsesses him: His sexual passion is awakened by the impossibility of sexual union. (This is also the theme of Samuel R. Delany’s famous story “Aye, and Gomorrah.”) The story’s title, of course, comes from Keats’s poem “La Belle Dame sans Merci,” in which a knight’s life is destroyed by his encounter with a beautiful fairy, an encounter with otherness that infects him with a permanent obsession that becomes a wasting disease.

But Tiptree’s stories often suggest that pathology dictates the typical patterns of relation between human men and human women. In “The Women Men Don’t See” the women of the title are not sexually desirable to the man who narrates the story and are therefore invisible to him; he only sees them at all when he’s trying to decide whether they are potential sex partners, or rather sex objects. One of the women, the mother of the other one, understands this, and says to him,

“Think of us as opossums, Don. Did you know there are opossums living all over? Even in New York City.”

I smile back with my neck prickling. I thought I was the paranoid one.

“Men and women aren’t different species, Ruth. Women do everything men do.”

“Do they?”

When, later in the story, Don discovers that the woman has planned an encounter with aliens and wants to be abducted by them, taken away from Earth, his first response is to try to shoot the aliens — but (of course; the story is very on-the-nose in multiple respects) he ends up shooting Ruth instead. She is not badly wounded, and later they have a final conversation.

“I think they’re gentle,” she mutters.

“For Christ’s sake, Ruth, they’re aliens!”

“I’m used to it,” she says absently.

Living with men, living with other terrestrial species, living with aliens — it’s all the same to Ruth. (It’s no accident that she shares a name with the biblical character who leaves her homeland to dwell among strangers.) To the aliens, who insist in halting and malformed English that they are students, that they want to learn rather than harm, she will be an object of intense attention — they will see her. But is that kind of being-seen any better, really, than being invisible? She stakes her life on the possibility, however remote, that it will be; because she has no hope at all for the world she was born into.

“Houston, Houston, Do You Read?” — another haunting but schematic story — imagines a future in which, by some kind of time-accident, three astronauts are thrown forward into a future world in which all living humans are female clones. They are rescued from their ship and brought into one occupied by five women. Under the influence of a disinhibiting drug, the astronauts reveal their true impulses: one of them is consumed by a mania for domination, a second is consumed by violent sexual lusts, and the third, the classic “beta male,” feels both of those impulses but in a muted way. (I told you the story is schematic.) It seems obvious to the women — who observe these men with a kind of detached curiosity, as, perhaps, the aliens in “The Women Men Don’t See” will observe Ruth and her daughter — that the re-introduction of males into human society, a re-establishment of the old ways of sexual reproduction, would be a Very Bad Idea Indeed. Difference is interesting to them, perhaps, but after several hundred years of life without men it’s not interesting enough to make them want to change their social order. Much alienation, little allurement.

In the darkest Tiptree stories, the allurements of difference are depicted as fundamentally irrational impulses — irrational, but so powerful that they don’t allow for the calm decisions to separate and isolate that mark the decisive moments in “The Women Men Don’t See” and “Houston, Houston, Do You Read?” The fantastically weird “Love Is the Plan the Plan Is Death” describes a species of creature, right on the cusp of sentience, one member of which tries to find ways to override the impulse to eat what you love. It turns out, though, that he, being male, isn’t one of the eaters; and that sometimes creatures do what they’d rather not do — if that’s The Plan. And in what seems to me Tiptree’s darkest story, “A Momentary Taste of Being,” the human passion to reach the stars is nothing other than the impulse that drives spermatozoa into a hostile environment where almost all of them will die.

Difference can be profoundly alluring, these stories seem collectively to say, but we should heed the countervailing feeling of alienation — if we can. It would be rational … but, in the end, how powerful is reason?

It’s fascinating to read these stories in our present moment, in which race occupies essentially the same cultural territory that sex occupied for Alice Sheldon and other women of her time. I suspect that Sheldon would have thought and maybe even felt differently about the alienation/allurement dialectic if she had had available to her our culture’s passionate commitment to gender as a social construct that is (therefore, so the faulty logic goes) amenable to infinite performative manipulation by individuals. For us, it’s racial difference that is especially often experienced in the way that Sheldon experienced sexual difference. When Reni Eddo-Lodge wrote Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race she was basically making the decision that the women in “Houston, Houston, Do You Read?” make about men.

The homologies between racism and sexism are not new, of course, and we can trace them back a long way: for instance, it’s worthwhile, I think, to map the concerns of “The Women Men Don’t See” onto the similarly knotted tension between not-being-seen and being-seen-badly in Ellison’s Invisible Man. But because race is such a massive component of our current political disputes, people now commonly choose and indeed embrace alienation in that whole sphere. (I’ve have recently learned that a large family of my acquaintance, well known for its cheerful closeness, has now been divided and broken by disagreements over Donald Trump. And at least some members of the family feel that it would be morally irresponsible not to be so broken.)

I think it’s because race is so widely seen to be intractably binary — Whites and Others — while gender and even sex are seen as chosen and performative that racial tension has taken hold of our public imagination in ways that the #MeToo movement, in the end, didn’t. Think for instance of New York Governor Andrew Cuomo: his behavior towards women has been despicable, but he easily survived the outrage, which proved to last only a few days. (Alice Sheldon would not have been surprised by the behavior or the tolerance of it.) If his sins had been equal in seriousness but racist in character — if he had demonstrably treated Black people around him with the same callous manipulative disregard that he treated the women who worked for him — would he have a job now? The question answers itself.

(Of course, if he had been a Republican governor, then he would have had the smoothest sailing imaginable. Openly, bluntly racist figures are perfectly welcome in today’s GOP; it’s only critics of Donald Trump who aren’t. But that’s a story for another day.)

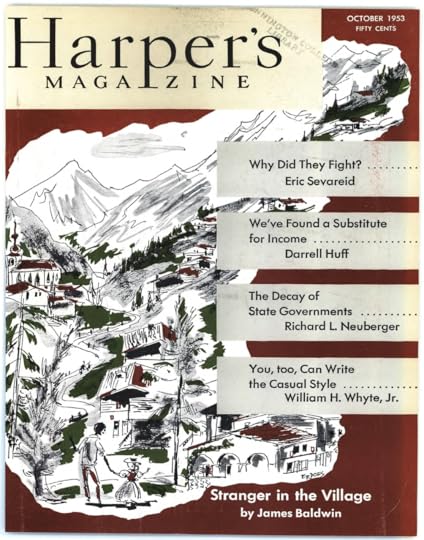

By way of conclusion, I’m going to make a simplistic statement that I may perhaps be able to unpack later: I believe that what we need when thinking about all forms of difference is (a) a frank acknowledgement of both allurement and alienation, and (b) an ability to achieve a genuinely tragic sense of history that does not succumb to despair. We should begin, collectively, by reading James Baldwin’s essay “Stranger in the Village.”

July 3, 2021

credit

Thomas Tuchel is known as a skilled practitioner of modern atacking football, but when he got to Chelsea in the middle of last season the first thing he attended to was his team’s defending. Under Frank Lampard the side had been leaking goals at an alarming rate, and Tuchel was content to set aside his tactical preferences for a while in order to plug the leakage. Chelsea’s first few games under Tuchel weren’t exciting, but they almost completely shut down opposing attacks, and then, with that foundation in place, Tuchel turned to the task of expanding his side’s offensive repertoire.

In these Euros, Gareth Southgate has done much the same for England. I complained in the group phase about his conservatism, but after today’s thrashing of Ukraine, it’s easy for me (and everybody else!) to see the wisdom of his approach. In the group stage they scored one, zero, and one; then against Germany they scored two; and now against Ukraine four. But they have yet to give up a single goal. It seems that this England squad, like Tuchel’s Chelsea, has learned that when you have well-earned confidence in your defending, then you can grow ever more ambitious and creative in attack.

So: a big thumbs-up to Gareth Southgate.

Looking ahead: On current form an England-Italy final is obviously the more likely, but all four sides are playing well and, even more important, are very well-balanced, with few evident weaknesses. I expect Italy to exploit Spain’s defensive limitations, and England to wear down Denmark; but no result would surprise me, and these are four very likable sides to boot. I will of course be cheering for England all the way, but I would be happy to see any of these four teams lift the trophy at tournament’s end.

July 2, 2021

tales of technocracy

The chief theme of my book The Year of Our Lord 1943 is that, in the midst of World War II, a series of Christian writers and thinkers discerned that the Allied victory over the Axis powers would be perceived not as a victory of democracy over tyranny but rather as a victory of technology. They sought to recommend humanistic models of education that would counterbalance the coming Novus Ordo Seculorum. But they were not successful, at least on their own terms; technocracy arrived, and dominated. Today’s surveillance capitalism is the product, in quite direct ways, of the particular form taken by the Allied victory in World War II.

I have just been re-reading some books that I first read almost fifty years ago — Isaac Asimov’s original Foundation trilogy and Arthur C. Clarke’s Childhood’s End — and am struck by how much they have in common, and how strongly they echo the themes of my story. Asimov’s three novels were originally published as stories between 1942 and 1950, then stitched together into novels; Childhood’s End was written in 1952. Clarke’s book is far, far more technically accomplished than Asimov’s creaky contraptions, and they differ dramatically in scale and setting: Clarke’s story treats of events that span a century on near-future Earth, while Asimov’s trilogy covers several hundred years and ranges around the entire galaxy. But their core concerns are remarkably similar, and are the product of the same historical moment to which my five Christian intellectuals in YOOL1943 were responding.

In the Foundation books a man comes to understand the historical development of humanity, past and future, and implements a plan for directing it; in Childhood’s End aliens who understand the historical development of humanity, past and future, come to Earth to implement a plan for directing it.

In both cases the new planned order successfully displaces an existing political structure quite like our own: unequal, decadent, sclerotic, tired.

In both cases satisfaction with the new order gives way eventually to a kind of complacency. In Asimov’s fictional world, the planet Terminus, guided by the science of the Foundation, comes to dominate its sector of the galaxy, but perhaps at the cost of its soul; in Childhood’s End, “The end of strife and conflict of all kinds had also meant the virtual end of creative art. There were myriads of performers, amateur and professional, yet there had been no really outstanding new works of literature, music, painting, or sculpture for a generation. … It was a much fairer, but a much smaller, planet than it had been a century before. When the Overlords had abolished war and hunger and disease, they had also abolished adventure.” Technocracy is powerful, and once a society experiences its blessings a return to an earlier status quo is unthinkable; yet as time goes by thoughtful people, knowing what technocracy enables, can’t help reflecting on what it inhibits or flatly disables.

The parallels eventually give way to significant divergences: Clarke is interested in imagining new and strange evolutionary pathways for humanity; Asimov wants to suggest that all empires follow the path Gibbon traced for Rome, energetic success giving way to decadence. But it’s noteworthy that both of them are so deeply invested in thinking about the ways old political orders give way to self-proclaimed Utopias; and both, also, see that the technocratic Utopia — as distinguished, I think, from the more traditional Utopias of authoritarian and totalitarian states — is a new thing in the world.

July 1, 2021

excerpt from my Sent folder: the Hitchens unit

You know, we could really get into the spirit of modern administration and come up with a way to measure the influence of public intellectuals. Perhaps the scale could be based on the Hitchens unit, one Hitchens (h) being the amount of public mindspace occupied by Christopher Hitchens in one year. I could then say that in the most recent fiscal year I delivered 0.02h, down, alas, from the previous year’s 0.035h. I could also articulate a Five-Year Plan for getting annual delivery up to 0.1h, with my really long-term goal being the achievement of a lifetime score of 1h.

June 30, 2021

don’t

DEI

That brings us to a final problem with [Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion] statements in hiring processes. Selecting for “correct” social views increases incentives to flatter and lie. Most faculty job applicants have spent two or more decades impressing teachers. It should be no surprise if they know what academic interviewers want to hear. (Or at least what the administration says interviewers should want.) Some of the people speaking insincerely will no doubt be passionate teachers and scholars willing to jump through hoops for an opportunity to do good work, but others will be slippery careerists who thrive by flattering. Why give them more chances to leverage their skills?

This is correct. The demanding of DEI statements from academic job candidates has nothing to do with the pursuit of social justice. Its purpose, rather, is to test candidates for subservience; to weed out those who ask difficult questions or exhibit independence of mind.

Alan Jacobs's Blog

- Alan Jacobs's profile

- 534 followers