Alan Jacobs's Blog, page 168

June 15, 2021

Betjeman & Burnham

You probably don’t expect to see an essay that links John Betjeman and Bo Burnham. I certainly didn’t expect to write one, but I did.

When I first came across Bo Burnham’s videos, several years ago now, I didn’t care for them at all. I thought he was childishly eager to pluck all the lowest-hanging comic-satirical fruit, and was all too eager to flatter the sensibilities of his audience. So I stopped paying attention to what he was doing. But people were praising his new Netflix special so extravagently that I had to check it out, if only so I could say how wrong everyone is.

Instead, I loved it. I think it is a tremendously successful and genuinely significant work of art. I keep thinking: I’m having this reaction to a Bo Burnham show?? And yeah, I am.

June 13, 2021

Gorey as designer

Rosemary Hill on Edward Gorey:

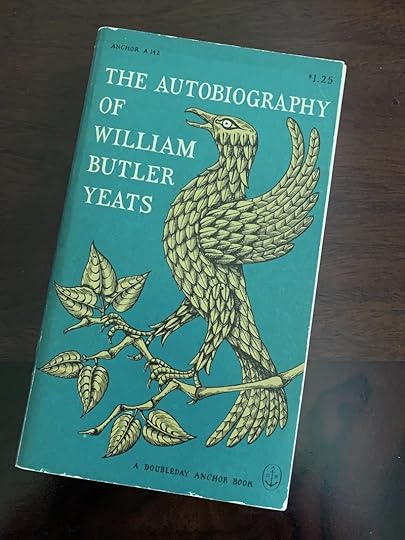

Gorey’s first book, The Unstrung Harp, was published in 1953, the year he moved to New York. He was working for Anchor Books, a new imprint of Doubleday, set up for the production of ‘quality literature … in mass-market paperback format’. Despite his own literary ambitions and the fact that he was trying and failing to write a novel, Gorey wasn’t employed on the editorial side but in the art department, where he worked variously as a cover artist and book designer. It was here that he hit on the form and order that [his former teacher John] Ciardi saw he needed. Having no training in typographic design, he found marking up layouts for the printer difficult. In an early example of what Dery calls his avant-retroism, Gorey decided that rather than look up all the fonts and calculate the point sizes it was ‘simply easier to hand-letter the whole thing’. The use of manual processes to imitate technical ones became an essential feature of his work. The delicate cross-hatching that gives his monochrome illustrations the velvety depth of 19th-century engravings was all done by hand with a crow quill dip pen. Having worked out his modus operandi, Gorey became ‘fast and competent’ at his job and used the rest of his time at the office to produce his own books.

Here’s an example, from a copy I bought at a used book store in, I think, 1976:

MbM

People get paid to do minute-by-minute reports on matches, but they’re never as good as the ones my son and I do. The “Yorkshire Pirlo” is Kalvin Phillips, who has been the man of this match (England-Croatia), so far anyway.

Sourdough

Auden used to say that he had a kind of guardian angel who was always there to tell him what to read next. I sometimes I think I have one too, though my angel is rather less consistently attentive than Auden’s was. But she has one habit I like: she tells me when not to read something. Yes, you’ll want to read that, she whispers, but wait. Wait a while. Not now, but later.

One book she told me to delay the reading of is Robin Sloan’s novel Sourdough — but recently she gave me permission, and I eagerly, um, devoured it. What an absolutely delightful tale! I recommend it to you all, as soon as your reading angel — you have one, I trust — gives you the O.K.

One of the great things about Sourdough is that it’s an utterly charming story that opens up, at the end, towards a future that could be quite utopian … or, marginal chance, quite dystopian.

June 12, 2021

Thanks be to God that Christian Eriksen is alive, and I p...

Thanks be to God that Christian Eriksen is alive, and I pray that he will make a full recovery. But I have to say, the sight of his teammates standing in a circle around their fallen comrade, protecting him, as the medics frantically worked to revive him, from prying and gawking eyes, is one that I will remember for the rest of my life.

June 10, 2021

Wondering how to decide what to read? Here’s a simple but...

Wondering how to decide what to read? Here’s a simple but effective heuristic to cut down the choices significantly. Ask yourself one question: Does this writer make bank when we hate one another? And if the answer is yes, don’t read that writer.

a kind of parable

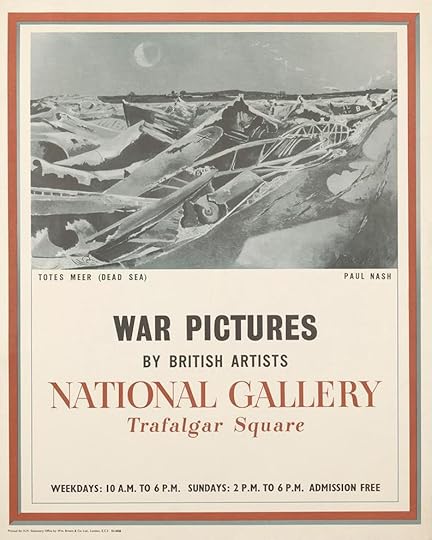

In yesterday’s post I mentioned the upsurge in the British public’s interest in art during the Second World War. Exhibitions like the one advertised above were all over London — you see several of them in Out of Chaos — and the National Gallery could show the work of living artists because it had empty walls: all of the works of the dead ones had been packed up —

— and moved to an unused mine, called the Manod Caves, in north Wales:

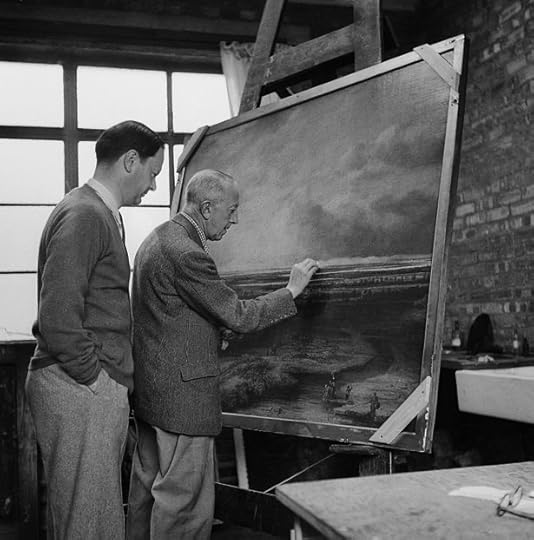

For certain staff members this was not the worst thing that could have happened. The two chief restorers, W.A. Holder and Helmut Ruhemann, now had the opportunity to attend to damaged or merely age-worn paintings in solitude and with all the time they needed. Here’s Holder with Sir Kenneth Clark — later to become world-famous thanks to Civilisation, but then the director of the National Gallery:

The windows in the background suggest that this photo was not taken in the Manod Caves but rather in one of above-ground locations in Wales where the pictures had originally been moved before Clark decided that they weren’t safe enough. (Many more excellent photos of the Great Removal may be found here.)

Ruhemann didn’t stay in Wales long — he took other jobs during the war, though eventually he returned to the National Gallery — but Holder worked in the caves for the duration. I like to think of him there, laboring patiently, quietly, persistently to repair and restore beautiful objects — works born of insight, imagination, and craft but damaged by neglect and the relentless passage of time. Outside the world is convulsed, and God bless those who fight for all they’re worth against its evils, but some of us are called to protect and preserve and restore our inheritance, waiting and hoping for better days, days when we emerge bearing what we have repaired to announce our heartfelt invitation.

June 9, 2021

Out of Chaos

Jill Craigie (1911-1999) was an extraordinary and (in my country anyway) insufficiently well-known figure. Born in London to a Scottish father and Russian mother, she became an actress, a filmmaker, a feminist and historian of feminism, and spouse to the Labour Party giant Michael Foot. Marrying an exceptionally famous man eclipsed the rest of her varied career, alas.

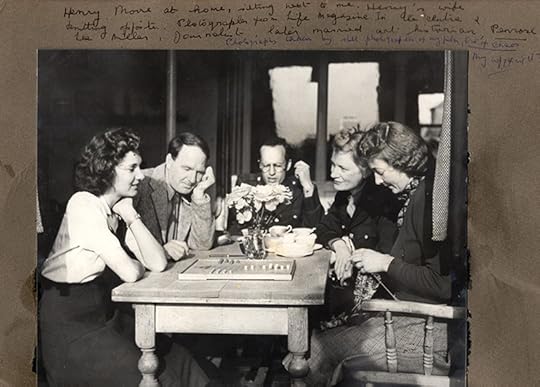

In the midst of World War II she wrote, directed, and narrated a fascinating short documentary called Out of Chaos (1944). If you’re in the U.K. you can follow that link to watch the whole film, but elsewhere you’ll need a VPN. The topic of the film is the dramatic upsurge in the British public’s interest in art during the war, and the film covers a remarkable array of people and activities in its 27 minutes. Here’s a picture, taken during the making of the film, of Craigie and the great Stanley Spencer:

That’s Spencer in the foreground (I don’t know who that is standing next to Craigie). Here they are again:

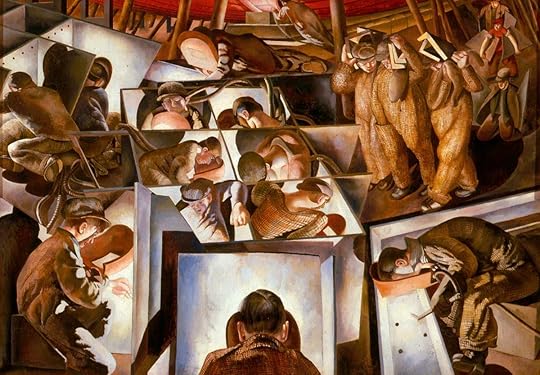

Craigie’s camera follows Spencer as he makes the first sketches for his magnificent Shipbuilding on the Clyde paintings — and shows those sketches to the shipbuilders.

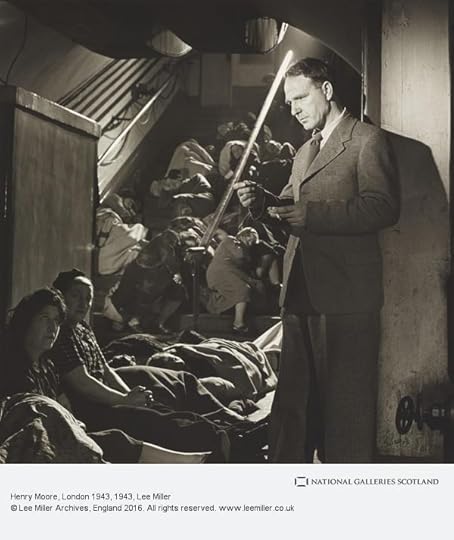

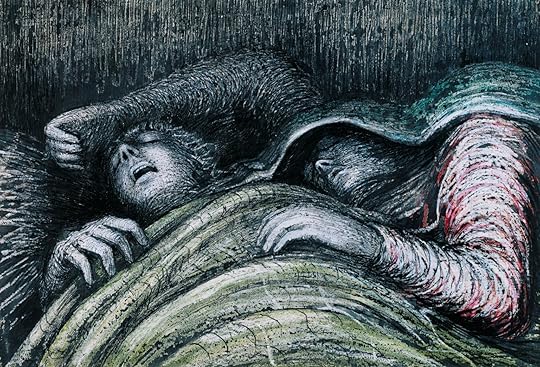

The elfin quickness of Spencer contrasts wonderfully with the calm solidity of Henry Moore, whom we see making sketches for his later-to-be-famous drawings of Londoners during the Blitz sheltering in the Underground. (I think the image below, and most of the scenes of Moore in the film, are re-enactments. In later years he explained that he and his wife had seen these sleepers in the Tube and had been greatly struck by them — the long lines of sleepers reminded him of Africans crowded into slave ships — but out of respect he waited until he was well out of their presence before beginning his sketches.)

Perhaps the most extraordinary scene in the film shows Moore, first with a wax pencil and then with paint, making one of his drawings:

— this one:

There’s so much in this film — even with all this I have only scratched the surface. It’s a miracle of narrative complexity and compression.

Not long ago a film about Craigie’s life was made — I hope to see it. And to get to know more of her work.

All Saints Chapel

John Piper, All Saints Chapel, Bath (1942); Tate Britain: “Piper already had a reputation as a painter of historic architecture, in particular of ruined buildings, when he was commissioned to record war damage. He had painted in Bristol and the Houses of Parliament when Bath was bombed on the nights of 25, 26 and 27 April 1942 in some of the first ‘Baedeker raids’, so called because the targets were cultural rather than strategic and said to be selected from the pre-war Baedeker guide books. Piper went quickly to Bath when, he recorded, the ‘ruins were still smouldering and bodies being dug out.’”

Alan Jacobs's Blog

- Alan Jacobs's profile

- 534 followers