Alan Jacobs's Blog, page 169

June 9, 2021

June 8, 2021

not giving up

One way to describe the Invitation and Repair project is to say that it’s for people who haven’t given up. One should always be hesitant to make broad social generalizations by haunting social media platforms or the websites that have become parasitical on social media — i.e., most newspapers and magazines —, but it’s clear that that world, at least, is dominated by people who have given up on some things that no healthy society ever gives up on.

People drag supposed racists or transphobes or whatever on Twitter because they have given up on achieving real social change.

Politicians strut and fret their hour on the social-media stage because they have given up on meaningful legislative work.

Partisans smear and mock those who disagree with them because they have given up on persuasion.

Journalists default to advovacy because they have given up on finding and telling the truth.

Readers and viewers of journalism seek and share misinformation because they have given up on learning the truth.

Violent thugs assault the U.S. Capitol or loot their own neighborhoods because they have given up on democracy.

All of the good things given up on require hard, patient work; none of the replacements do. They’re easy and quick; they promise immediate rewards (though whether what they in fact give amounts to “rewards” is a matter for debate). But when we invite and repair we manifest hope: we look towards a future of cooperative endeavor — cooperative discovery, cooperative healing.

The hopeful refuse mindslaughter; the hopeful join the United Front Against Bullshit.

Conservatives tell me that we’re right on the verge of a ...

Conservatives tell me that we’re right on the verge of a hard-left takeover of the entire country, which will inevitably put an end to democracy and personal freedom. Leftists tell me that we’re right on the verge of a Trumpist takeover of the entire country, which will inevitably put an end to democracy and personal freedom. So the only thing I know for sure is that I am about to be enslaved; I just don’t know who my enslavers will be.

June 6, 2021

le mot juste

Maurice Bowra was an Oxford don legendary for his social activities, his malicious wit, and his bullhorn voice. Once, in the 1930s, he met an elegant German who was visiting England to participate in a kind of charm offensive on behalf of the Nazi regime. (This was common in those days: Hitler had people working hard to gain the approval of Oxford and Cambridge dons.) At one point in the conversation, Bowra stood up and told the man, “I know what you are. You are a Nazi.” And then he added, “I look forward one day to using your skull as an inkpot.”

I am in awe of the ingenuity Bowra manifested that day, and will keep his lapidary phrase hidden away in my bosom in case I should require it. Someone writes a slashing review of one of my books? Dear X, I look forward one day to using your skull as an inkpot. Someone cuts me off on the interstate? I lean out the window: I look forward one day to using your skull as an inkpot. It’s absolutely perfect.

June 5, 2021

Light Perpetual

And speaking of novels by friends, Francis Spufford’s Light Perpetual is now available in the U.S. I cannot recommend it to you too highly. This novel absolutely did me in — I found myself deeply invested in each of its five main characters, and at the end simultaneously heartbroken and exhilarated. Please do not miss this one.

(I find it very interesting to reflect on the peculiar commonalities between two books that on most levels are dramatically different, Light Perpetual and — see previous post — Purgatory Mount. But I can’t talk about those connections without utterly spoiling both books….)

the meaning of Purgatory

I read Adam Roberts’s Purgatory Mount in draft, and struggled to know what to make of it. I have now read its final version, and find it an exceptionally resonant and moving story – though I acknowledge that people who aren’t comfortable with Adam’s peculiarly associative intelligence (imagine his mind comprised of chess pieces, all of them knights) may find some of the narrative linkages he forges here difficult to parse. And Adam shares with certain other writers, most notably Auden and Pynchon, a tendency to cast his most serious inquiries in comic form.

As I set the book aside, I found myself thinking several thoughts:

That culture is what we humans make together;That culture is memory;That memory is imperfect;That among the things we remember will always be sins and wrongs, those done to us, and those we do to others;That the Book of Common Prayer teaches us something utterly inevitable about “these our misdoings,” namely that “the remembrance of them is grievous unto us, the burden of them is intolerable”;That, therefore, much of the essential work of culture – always – is the addressing of such remembrances and such burdens; and, finally,That this work must often be done in extraordinarily difficult circumstances, not least because of the imperfections of memory and the imperfections of the people who remember.Some years ago Adam and I joined with Rowan Williams and Francis Spufford for a theological conversation about Adam’s novel The Thing Itself; Purgatory Mount is also a novel that cries out for theological reflection. I hope it gets it.

The two epigraphs that Adam prepends to his story are wisely and wittily chosen, but I would like to suggest one more, from “East Coker”:

There is only the fight to recover what has been lost

And found and lost again and again: and now, under conditions

That seem unpropitious. But perhaps neither gain nor loss.

For us, there is only the trying. The rest is not our business.

June 4, 2021

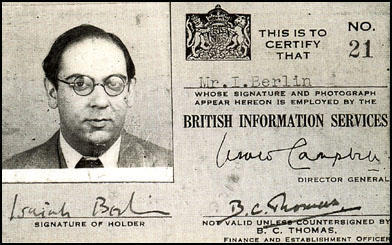

Berlins

One of the best stories in Michael Ignatieff’s biography of Isaiah Berlin involves a luncheon hosted at 10 Downing Street in 1944. Berlin had been for almost the whole of the war living in the USA, socializing and schmoozing and conspiring in his inimitable fashion and then sending back briskly incisive weekly reports on American attitudes towards the war effort and towards Great Britain in general. Churchill appreciated those reports very much and was pleased to have the opportunity to meet the man who had written them.

But when he started asking his guest questions about America, he was surprised and puzzled by the vagueness and diffidence of the answers. Eventually, having gotten nowhere and feeling a bit desperate, the Prime Minister asked him what he thought was the best thing he had written.

Came the reply: “White Christmas.”

Isaiah Berlin was in Washington. The P.M.’s luncheon guest, it turned out, was Irving.

June 3, 2021

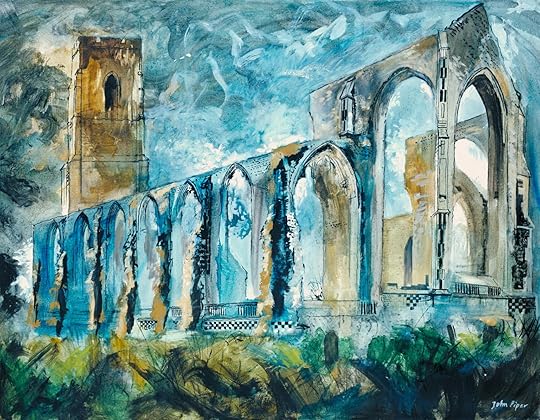

Collett’s England

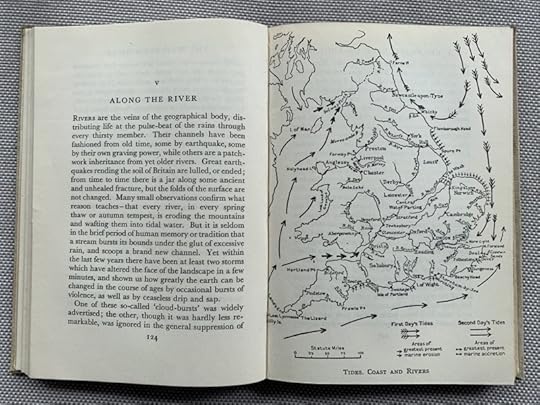

One of Auden’s favorite books was Anthony Collett’s The Changing Face of England (1926), and it’s easy to see why — it’s absolutely delightful. Here’s a passage from the chapter seen above:

It is curious to see how floods restore the ancient aspect of the valley landscape, by overflowing the modern chequer-work of fences and hedges, and showing where floods held the field before. Only new houses are flooded when Thames or Medway, or any stream of the populous half-urban valleys, breaks bounds. Bungalows become uninhabitable, swans cruise through rose-beds, but the old farmhouses stand securely dryshod, though scarcely fifty yards from the insurgent water, and perched on so slight a rise as to be invisible until the water came. Old farms and cottages were built with exact knowledge, from experience and tradition, of how far the flood would reach. New houses are plumped down into the channels by which the river disgorges, as though it would never return.

And a luminous passage from another chapter, on Epping Forest:

Yet even in England, woods with a touch of the terror of infinity still survive; and it is one of the strangest things about Epping Forest that, for all its nearness to the East End of London, and its permeation from end to end with the noise of traffic, it yields not only a hundred delightful pictures of the cheerful greenwood, but one or two of the more ancient and formidable type. From the hamlet of Baldwin’s Hill, near Loughton — red omnibuses run close behind it — there is a view across a narrow valley to a flank of the forest rising, beech beyond beech, hornbeam beyond hornbeam, pollarded and rounded, and innumerable as sheep streaming downhill to water, which is full of the true forest sense. Those who walk in the forest soon learn that the great road to Epping and the eastern counties is never a mile away, and that the air is seldom empty of its rumour. But while the ear tells continually of London, the eye carries us far back into Shakespeare’s age, and the old time beyond. Dull streets cease abruptly at the forest’s edge; the bell of the muffin-man echoes on autumn afternoons among the beech-boles hacked by spotted woodpeckers. Silence falls a moment, and we hear the deer belling in the glades; it is one step from Bethnal Green into Broceliande.

In the Hebrew school, sitting on plank benches with timbe...

In the Hebrew school, sitting on plank benches with timber-cutters’ children, Isaiah received his first formal religious instruction. It was also his first experience of schooling, and to the end of his life he could still remember the words of a song he learned with the other children, about the stove in the corner that kept a poor family warm. From an old rabbi, he learned the letters of the Hebrew alphabet. The rabbi too was never forgotten. Once he paused and said, ‘Dear children, when you get older, you will realise how in every one of these letters there is Jewish blood and Jewish tears.’ When Berlin told me this story, eighty years later, in the downstairs sitting room of his home in Oxford, Headington House, for a split second his composure deserted him and he stared out across the garden. Then he looked back at me, equanimity restored, and said, ‘That is the history of the Jews.’

— Michael Ignatieff, Isaiah Berlin: A Life

June 2, 2021

re: Foucault

A brief and belated thought on Ross Douthat’s column on Foucault and conservatism: It’s worth noting that Jürgen Habermas called Foucault a “young conservative” back in 1981, a claim explicated and expanded brilliantly by Nancy Fraser in this essay from 1985. Fraser’s essay, combined with my own experience teaching Foucault to evangelical Christian undergraduates, led me to make this comment twenty-one years ago, in which I said that my students’

sympathetic openness means that they learn a lot from theory that makes them better, more acute readers and critics. And some theoretical approaches enable them to find sophisticated modes of interpretation that complement, develop, and add nuance to their Christian faith without emptying it of its power. (I have found them to be particularly engaged by Gadamer, Bakhtin, and Levinas, and by the rabbinical scrupulosity of much of Derrida’s work. They also get a sinister pleasure from reading Foucault, who is after all a kind of Calvinist, only without God — Michael Warner is right to say that if you think Foucault is suspicious of the human order, try reading Jonathan Edwards. So Foucault is in a weird way one of us.)

Alan Jacobs's Blog

- Alan Jacobs's profile

- 533 followers