Alan Jacobs's Blog, page 164

June 28, 2021

economies

When, in August 1860, John Ruskin published an essay in Cornhill Magazine – an essay that would later become the first chapter of his book Unto This Last readers were appalled by his argument that all workmen in a given profession should be paid the same, no matter whether they do their work well or badly. When he published Unto This Last, he said “it is a matter of regret to me that the most startling of all statements in them, – that respecting the necessity of the organization of labour, with fixed wages, – should have found its way into the first essay; it being quite one of the least important, though by no means the least certain, of the positions to be defended.”

But this insistence on the insignificance of his “startling” statement is belied by the title that he chose for the book. “Unto this last” is a line uttered by Jesus in the parable of the workers in the vineyard, in which the owner of the vineyard pays the people the workers who arrive at the end of the day the same that he pays those who worked all day long. This is of course a parable of the Kingdom, because all of Jesus’s parables are: the simplest point is that those who arrive late in the narrative of God’s redemptive work in the world, e.g. the Gentiles who hear Jesus’s message as opposed to the Jews who have been a part of this covenant history for hundreds and hundreds of years, are welcome to the same reward of eternal life that the old-timers are. It is not, most interpreters agree, a story about the principles of political economy. But nothing could be more characteristic of Ruskin’s thought that his belief that it is a principle of political economy, indeed the key principle of political economy, which is why he titles his book as he does.

Right from the beginning of Unto This Last Ruskin insists upon one governing point: that in thinking of political economy it is impermissible to treat human beings as what we today might call rational actors, people who simply maximize their own economic well-being, even when that comes at the expense of others. Or especially when it comes at the expense of others.

Disputant after disputant vainly strives to show that the interests of the masters are, or are not, antagonistic to those of the men: none of the pleaders ever seeming to remember that it does not absolutely or always follow that the persons must he antagonistic because their interests are. If there is only a crust of bread in the house, and mother and children are starving, their interests are not the same. If the mother eats it, the children want it; if the children eat it, the mother must go hungry to her work. Yet it does not necessarily follow that there will be “antagonism” between them, that they will fight for the crust, and that the mother, being strongest, will get it, and eat it. Neither, in any other case, whatever the relations of the persons may be, can it be assumed for certain that, because their interests are diverse, they must necessarily regard each other with hostility, and use violence or cunning to obtain the advantage.

For Ruskin, human beings are never purely economic (in our usual sense of that term) in their motives and actions, but are always actuated in considerable part by their affections. Another way to put this is to say that Ruskin thinks that political economy needs to take the gift economy into account as well as the market economy, and his bizarre (or apparently bizarre) plan for paying workers is a natural outgrowth of this emphasis.

More on all this in due course.

June 27, 2021

on re-reading Acts

I’ve been re-reading the book of Acts, and my chief response this time is: It’s wonderfully encouraging to see how bluntly and unapologetically Luke records a chronicle of confusion, ineptitude, and misdirected enthusiasm. The apostles are often a collective mess, and Luke does nothing to hide that from us. I find this strangely consoling.

It’s also fascinating to note how little the apostles understand the message they been entrusted with. They know that Jesus is the Christ, the promised Messiah of Israel, and they know that the Christ’s own people rejected him and demanded his death – but beyond that they’re a little fuzzy about what the life, death, resurrection, and ascension of Jesus mean. The idea that what Jesus offers them (and all of us) is God’s limitless grace is rarely mentioned. It’s there, but only in tentative and vaguely articulated form.

The Reformation’s idea of returning to the apostolic church is therefore, I think, only partly right. We want their spirit – their enthusiasm, their boldness in proclamation, their trust in God, their loving care for one another – but we don’t want their ignorance. How to develop theological depth and complexity without acquiring an accompanying institutional structure that tends toward sclerosis, that makes the communal life of the church stiff and inflexible and disconnected from its natural missional energies – that is the ongoing problem that Christ’s church faces, just as much as the structurally similar problem of navigating between legalism and antinomianism.

We don’t navigate those complexities very well, and never have, in large part because of pride. Every time a new Christian movement arises in a place where there is a dominant form of church, that dominant form should be grateful to the dissenters, because the dissenters – who are not necessarily correct to dissent – nevertheless reveal to the dominant church the ways it has fallen short, the needs and desires it has failed to meet or address. (The flip side of this point is Auden’s contention that Kierkegaard should have been grateful to the Danish Lutheran Church for teaching him the very Bible in which he found the standards by which he condemned it.) Every dissent contains a lesson for those with ears to hear, for those whose ears are not closed by pride.

One more noteworthy point about this narrative: Again and again, in their disputes with the new Jesus sect, the leading rabbis try to get management to take their side, to the ongoing puzzlement and frustration of the Romans, who repeatedly ask, “How is this our business?” A Roman official even has one of the rabbis beaten to discourage him from further approaches, yet still the rabbis return and demand Roman intervention. And of course this is what Paul, another rabbi, does as well: King Agrippa even comments to the Roman procurator Festus that Paul could have been freed and set on his way if he hadn’t appealed to Caesar (which seems to have set some unstoppable legal machinery into motion).

The Jews had a lot of practice dealing with hostile or at least semi-hostile occupying powers; they had been doing it for hundreds of years – though if N. T. Wright is correct they developed a particular hatred of the Romans when Pompey entered and desecrated the Temple in 63 BC. (This hatred apparently intensified when no equivalent of Judas Maccabeus appeared to resist the oppressor.) That said, Simon Schama, in his Story of the Jews, notes that before Pompey had even entered Jerusalem several rival claimants for Jewish leadership visited him, serially, to enlist his support against the others. So hatred there may have been, but hatred doesn’t preclude calculation, intrigue, and trying to get management to take your side.

June 26, 2021

editing tools

The kind of work I’m doing right now — my critical edition of Auden’s book The Shield of Achilles — is somewhat unusual, but some readers might be interested in the tools I’m using to get it done.

The first thing I did was to go to AbeBooks and order four copies of early editions of the book, two of the American edition (Random House) and two of the British (Faber). These need to be scrupulously compared for differences.

I selected one of them — the earliest, which means an American edition (the book came out here several months before it did in the U.K.) — and made it my working copy. Before annotating it, I took photos of every page of the book. Then I went through the book with a highlighter, marking every word or phrase that I believe will require annotation.

I grabbed a pencil and, on the pages and on sticky notes, made initial comments on ideas that need to go into my Introduction, calling attention to related passages.

Then I returned to the photos of the text. I opened the Photos app on my Mac, navigated to the photo of the first page, and typed the keyboard shortcut I use to invoke TextSniper. TextSniper is a fabulous app. When you invoke it you get an area-selection tool. Draw a rectangle around any text on your screen and TextSniper OCRs the text and copies it to your clipboard. There are other ways I could do this: for instance, I could scan the book into a PDF and then use an app like PDFpen to OCR the whole text. But that brings in a lot of extraneous material, for instance anything in the pages’ headers and footers. With TextSniper I get precisely the text I want — and it is the most accurate OCR tool I have ever used, by a long shot. So Photos to TextSniper to BBEdit — and very shortly I had a complete text of the book to work from.

Next: Markup — in Markdown. In this case basically headings and italics — pretty simple work that only took a few minutes. I went from a bunch of digital photos to a clean, accurate working text in little more than half an hour.

As soon as you start the work of textual editing you need to generate comments (about formatting, for instance) and queries for the eventual copy editor. And since Microsoft Word is the lingua franca of publishing, I therefore had to convert my Markdown file to Word. Most of the time I use pandoc for such conversions, but I find that Brett Terpstra’s Marked does a better job of preserving line breaks — and a book of poems has a lot of line breaks.

(So why not just paste the OCR’d text directly into Word, instead of using a text file as the intermediate stage? Because, as you surely know, structuring text in Word is a nightmare. You try to turn one line into a header and Word decides to make the next paragraph part of the header and change the typeface of the previous paragraph. And then you can’t figure out how to fix it. A plain-text file structured with Markdown is precise. My primary governing rule of writing and text-editing: Never open Word until you absolutely have to.)

Okay, so then I had my accurate, ready-to-be-annotated text in a Word file. Which left me with one final workflow problem to solve: adding the annotations, which in the published edition will appear at the end of the text. There are several ways to do this, involving split screens or external monitors or even second computers. But here’s what I did: I got out my little-used iPad and connected it to my MacBook Air with Sidecar. Now I can look at the Word file of the book’s text on the iPad and add annotations in BBEdit on the Mac. Baby, I got a stew going!

June 25, 2021

civil disagreement

John Rose, on classes he teaches at Duke University:

To get students to stop self-censoring, a few agreed-on classroom principles are necessary. On the first day, I tell students that no one will be canceled, meaning no social or professional penalties for students resulting from things they say inside the class. If you believe in policing your fellow students, I say, you’re in the wrong room. I insist that good will should always be assumed, and that all opinions can be voiced, provided they are offered in the spirit of humility and charity. I give students a chance to talk about the fact that they can no longer talk. I let them share their anxieties about being socially or professionally penalized for dissenting. What students discover is that they are not alone in their misgivings. […]

On the last day of class this term, several of my students thanked their counterparts for the gift of civil disagreement. Students told me of unlikely new friendships made. Some existing friendships, previously strained by political differences, were mended. All of this should give hope to those worried that polarization has made dialogue impossible in the classroom. Not only is it possible, it’s what students pine for.

Please read the whole essay. After doing so, you may be encouraged, as Rose himself is. But you also may be depressed, as I am, to reflect that what ought to be the baseline norm of all university classes should be so much of an outlier that for many of Rose’s students it’s a one-time-only exceptional experience.

Also, there’s a mystery here, an important one: Many professors say that they’re all about open dialogue and the free play of ideas, but students are really good at discerning whether or not that’s bullshit. Like card players, all of us who teach have tells, quirks of speech or facial expression that let students know what we really think as opposed to what we say we think. Obviously John was able to convince his students that his commitment to civil discourse is real. How a teacher does that is the mystery I’m talking about, but the one essential step is for you, dear professor, to ask yourself whether you actually believe in the free play of ideas. Because if you don’t, you’re definitely not going to be able to persuade your students that you do.

June 24, 2021

two quotations: work

Welcome to hustle culture. It is obsessed with striving, relentlessly positive, devoid of humor and, once you notice it, impossible to escape. “Rise and Grind” is both the theme of a Nike ad campaign and the title of a book by a “Shark Tank” shark. New media upstarts like the Hustle, which produces a popular business newsletter and conference series, and One37pm, a content company created by the patron saint of hustling, Gary Vaynerchuk, glorify ambition not as a means to an end but as a lifestyle….

Perhaps we’ve all gotten a little hungry for meaning. Participation in organized religion is falling, especially among U.S. millennials. In San Francisco, where I live, I’ve noticed that the concept of productivity has taken on an almost spiritual dimension. Techies here have internalized the idea — rooted in the Protestant work ethic — that work is not something you do to get what you want; the work itself is all. Therefore any life hack or company perk that optimizes their day, allowing them to fit in even more work, is not just desirable but inherently good.

The pandemic has intensified a pressure to internalize the demand for constant work, with people striving to use their time in marketable ways, even if no boss is telling them to do so. Anderson sees the question about quarantine “passion projects” as a symptom of “the universalization of the concept of management altogether, whereby everyone is encouraged to think of themselves as ‘CEO of Myself.’” Indeed, much pandemic productivity discourse has centered not on getting things done because your employer makes you, but on getting things done because you make you.

In a viral tweet last April, for example, marketing CEO Jeremy Haynes argued that if you didn’t use lockdown to learn new skills or start a business, “you didn’t ever lack the time, you lacked the discipline.”

The implication was that people should use the supposed extra time provided by quarantine to squeeze additional labor out of themselves, doing the work of capitalism without even being asked to do so. We’re so used to treating our time — our very selves — as a resource for the market that we do so even during a global crisis. And when a boss isn’t buying our time — when it’s allegedly “free” — we’re supposed to figure out a way to sell it on our own.

“I’ve been working with young people on the cusp of adulthood for the past two years, and the problems they’ve brought my way have all tended to revolve around perceived failures to be their own CEO,” Anderson said.

See also: Alexa Hazel on Self-Taylorizing.

Are you still there?

Late Tuesday night, just as the Red Sox were beginning a top-of-the-eleventh rally against the Rays, my smart TV decided to ask me a question of deep ontological import:

Are you still there?

To establish my thereness (and thus be permitted to continue watching the game), I would need to “interact with the remote,” my TV informed me. I would need to respond to its signal with a signal of my own. At first, as I spent a harried few seconds finding the remote and interacting with it, I was annoyed by the interruption. But I quickly came to see it as endearing. Not because of the TV’s solicitude — the solicitude of a machine is just a gentle form of extortion — but because of the TV’s cluelessness. Though I was sitting just ten feet away from the set, peering intently into its screen, my smart TV couldn’t tell that I was watching it. It didn’t know where I was or what I was doing or even if I existed at all. That’s so cute.

I had found a gap in the surveillance system, but I knew it would soon be plugged.

Bible reading in style

I’ve written on several earlier occasions — e.g. here — about the delightful creativity of the good people at Crossway Books, who in my view don’t get the widespread love they deserve, and don’t get it simply because they publish a translation of the Bible, the English Standard Version (ESV), that some bien-pensant Christians denounce as too conservative. And maybe some of the choices those translators made are too conservative, but only a handful of passages are in dispute, and almost no one would notice any of them without prompting. The ESV is a fine translation and I find myself using it often simply because Crossway has created so many imaginative ways to engage with the text.

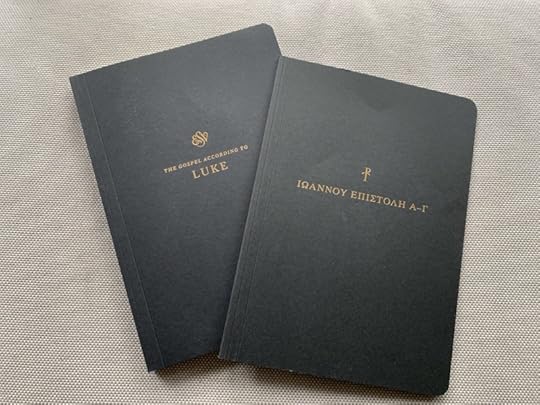

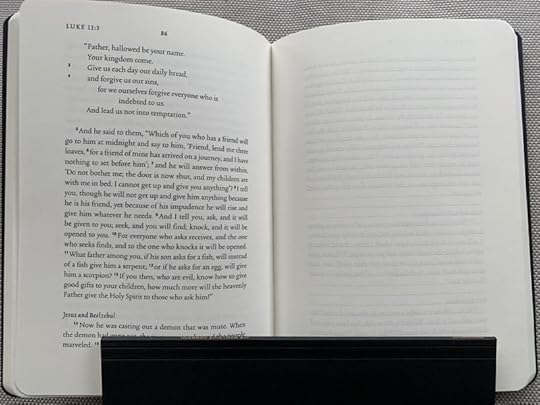

Consider, as examples, the two books pictured above, which I just purchased. The one on the left is the full text of the Gospel of Luke, printed like this:

The text is on the left page, with the right page reserved for annotation and commentary (something there’s never room enough for in a regular Bible). Note also the excellent typography, another element of book-making in which Crossway sets a standard few other publishers meet. I am very eager to begin a serious read-through of Luke with pen in hand.

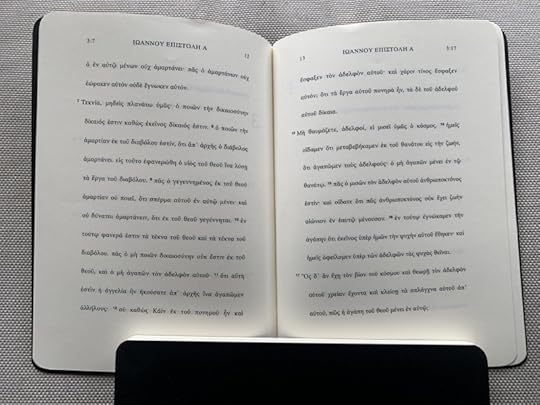

The other volume is the Greek text of the three letters of John:

In this case we don’t have whole pages devoted to annotation, but rather widely-spaced lines so readers can make interlinear comments, a format ideal for noting distinctive Greek words. This one too I will soon start using.

These are simply fabulous resources for people who want to read the Bible in a serious way — a market that Crossway almost alone seems to have noticed and cultivated.

June 23, 2021

Little Platoons

Matt Feeney’s Little Platoons: A Defense of Family in a Competitive Age is a fascinating and provocative book that, in my judgment anyway, cries out for a sequel.

Before I go any further I should say that I’ve known Matt for years – we used to be co-conspirators at The American Scene – and we’ve corresponded occasionally since then, though not recently.

If there is any one idea that conservatives are thought to share, it’s the belief that a healthy society needs healthy mediating institutions. This is the burden of Yuval Levin’s recent book A Time to Build, and Yuval (also a friend) makes this argument about as well as it can be made. We do not flourish either as individuals or as a society when there is nothing to mediate between the atomized individual and the massive power of the modern nation-state. That’s why it’s always, though especially now, “a time to build” those mediating institutions that collectively are known as “civil society.”

The really brilliant thing about Matt’s book — written by someone who, like me, possesses a conservative disposition but might not be issued a card by the people who authorize “card-carrying conservatives” — is its claim that in some areas of contemporary American life the mediating institutions are not too weak but rather too strong. And what he demonstrates with great acuity is the consistency with which those institutions, from youth soccer organizations to college admissions committees, have conscripted the “little platoon” of the family to serve their needs — indeed, to get families to compete with one another to serve those institutions’ needs:

What happens, though, when citizens direct their suspicion not at a coercive government but at their peers, with whom they find or feel themselves, as parents and families, in competition? I join a chorus of scholars and writers in observing that such a competitive mood abides among parents today. Less noticed is how such competition creates new forms of subservience and conformity among families. In this environment, the intermediate bodies of civil society, cornerstone of the conservative theory of republican liberty, sometimes become demanding bosses, taskmasters, and gatekeepers in the enterprise of winning advantage for our children in a system of zero-sum competition.

As a result,

Under these conditions, the anxious and competitive citizen-parent looks to certain “voluntary associations,” certain institutions within “civil society,” not as bulwarks against coercive government but as ways to gain advantage over other families, exclusive paths to better futures. From boutique preschools to competitive sports clubs to selective colleges and universities, desirable institutions become bidding objects for future-worried and status-conscious families.

Thus, “the era of intensive parenting is defined by the rise of a sort of hybrid entity, an institutional cyborg that is part organization and part family.”

Matt is not by any means opposed to these mediating institutions as such — there’s a wonderful section on how he learned, through walking his kids to school every day and then hanging out for a while with teachers and other parents, how a school really can be the locus of genuine community — but looks with a gimlet eye, a Foucauldian gimlet eye, on the ways that, right now, in this country, a few such institutions form, sustain and disseminate their power over families.

He’s scathing about college admissions, especially the turn towards “holistic” admissions processes which serve to transform mid-level administrators into eager shapers of souls. He mentions a Vice Provost at Emory who laments the imperfection of his knowledge of the inner lives of applicants, and continues:

If you recall that, twenty or thirty years ago, admissions departments weren’t even mentioning authenticity, were not treating the therapeutic search for true voices and true selves as the goal of their investigations, and if you devote a moment’s thought to the absurdity of this search, you will be tempted to laugh at Vice Provost Latting’s hysterical protest against imperfect knowledge. But, laughable as this and other admissions testimony is, on its merits, I would like to present a good reason not to laugh. Setting up a yearslong, quasi-therapeutic process in which you goad young people to lay bare their vulnerable selves to you, when this process is actually a high-value transaction in which you use your massive leverage to mold those selves to your liking, is actually a terrible thing to do.

Yes, it is. And I am glad to hear someone say it so bluntly.

In his conclusion, Matt admits his reluctance to give advice to parents in such a coercive and panoptic environment, and that’s perfectly understandable. In any case, the primary function of the the primary purpose of the book is diagnostic: he wants to show us the specific ways in which these various mediating institutions co-opt families, and even in some cases make the families hosts to which they are the parasites. I don’t think that the book would have held together as well if it had tried to include parenting advice in the midst of everything else. But it is obvious that Matt has thought quite a lot about what it means to be a responsible parent in our time – he has a great riff on why he’s okay with the fact that his oldest daughter is the only person in her class who doesn’t have a smartphone – and I would really like to hear more from him about how he conceives of the positive responsibilities of being a parent, the dispositions and actions which strengthen that little platoon. I don’t think he needs to do this in a pop-psychology self-help way; Matt is by training a philosopher and I think philosophical reflection on this topic, so essential to human flourishing, would be welcome from him.

But the book provides a great service simply by teasing out the ways in which families are not served by but rather are made to serve these parasitic institutions — and the ways in which we are manipulated to do so ever more intensely by our felt need to compete with other families. As we are always told, the first step is acknowledging that you have a problem.

June 22, 2021

Barney Ronay:

Chekhov came up with the idea of the shotgu...

Chekhov came up with the idea of the shotgun above the mantelpiece. If there’s a gun on the wall in Act 1 of your drama, someone had better be firing it by Act 2. By the same token if you have an abundance of attacking talent – dribblers, speed-merchants, velvet-touch princelings – at some point you really do need to encourage them to show it on the pitch.

For now Southgate seems to have rejected this dramatic rule in favour of something more diffuse. We appreciate and welcome guns as a basic principle. We have a wealth of promising guns in the pathway. We will, in due course, be reviewing their use as part of a wider process. Now. Shall we talk about right-backs for a bit?

Gareth Southgate indeed has “an abundance of attacking talent” at his disposal, and clearly considers this his cross to bear. What he wants is an entire team of Jordan Hendersons.

UPDATE AFTER THE MATCH: If Southgate hadn’t acted decisively to get his three most creative and dangerous players (Saka, Grealish, Sterling) off the pitch, England might have scored again. What a nightmare that would have been.

The players have mostly been very good, despite their manager’s desperate attempts to stifle them. I’m looking forward to the 8-1-1, with poor old Harry Kane lumbering along at the front of the line like one of the Walking Dead, that Southgate will deploy in the knockout round.

two poems in support of my recent posts

If we deny our happiness, resist our satisfaction,

we lessen the importance of their deprivation.

We must risk delight. We can do without pleasure,

but not delight. Not enjoyment. We must have

the stubbornness to accept our gladness in the ruthless

furnace of this world. To make injustice the only

measure of our attention is to praise the Devil.

— from “A Brief for the Defense” by Jack Gilbert

Love the quick profit, the annual raise,

vacation with pay. Want more

of everything ready-made. Be afraid

to know your neighbors and to die.

And you will have a window in your head.

Not even your future will be a mystery

any more. Your mind will be punched in a card

and shut away in a little drawer.

When they want you to buy something

they will call you. When they want you

to die for profit they will let you know.

So, friends, every day do something

that won’t compute. Love the Lord.

Love the world. Work for nothing.

Take all that you have and be poor.

Love someone who does not deserve it.

— from “Manifesto: The Mad Farmer Liberation Front” by Wendell Berry

Alan Jacobs's Blog

- Alan Jacobs's profile

- 529 followers