Alan Jacobs's Blog, page 160

August 2, 2021

As a follow-up to my recent posts on vaccination — one an...

As a follow-up to my recent posts on vaccination — one and two — I just want to say that it’s especially nice to see people in high-risk groups getting vaccinated.

unknown unknowns

In the first printing of my biography of the Book of Common Prayer, I say that Thomas Cranmer was a Fellow of Jesus College, Oxford. This is incorrect. It was Jesus College, Cambridge.

Now, I knew perfectly well that Cranmer was a Cambridge man. I just had a brain fart when I put him in Oxford. But the error has still nagged at me. I keep thinking: Would I have done that if I were English? That is, would the difference between Oxford and Cambridge be so vivid in an English person’s mind, especially an educated English person, that such a brain fart would be impossible? Or was it just a brain fart? Maybe in other circumstances I could with equal ease write that, say, Clarence Thomas’s J.D. is from Harvard or that FDR attended Yale.

I can’t be sure. But the whole episode has made me more aware of all the things natives of a country know that foreigners, even affectionate and well-informed foreigners, have no clue about. My Cranmer error has had me musing about the fact that, while my academic speciality is 20th-century British literature, I may be completely, blissfully (or not so blissfully) ignorant about all sorts of matters concerning the world my writers grew up in that would be obvious to natives of their country.

Indeed I know I have such blanks in my knowledge. When I produced a critical edition of Auden’s long poem The Age of Anxiety, I annotated this passage:

Listen courteously to us

Four reformers who have founded — why not? —

The Gung-Ho Group, the Ganymede Club

For homesick young angels, the Arctic League

Of Tropical Fish, the Tomboy Fund

For Blushing Brides and the Bide-a-wees

Of Sans-Souci, assembled again

For a Think-Fest …

Here’s what I wrote:

These titles are only partly explicable but are meant to suggest, ironically, that the four new acquaintances are the sort of people who would create social organizations devoted to good cheer and moral improvement. Ganymede was a beautiful young mortal who was abducted by Zeus to serve as the gods’ cupbearer; Auden may also have remembered the Junior Ganymede Club frequented by Jeeves and his fellow valets in the novels of P. G. Wodehouse. “Bide-a-wee” is a Scots phrase meaning “stay a while.” “Sans-souci” means “without care.”

None of this is wrong … but: that excellent writer (and biographer of Auden) Richard Davenport-Hines wrote me to say that

Sans Souci (in addition to being Frederick the Great’s summer palace at Potsdam) was together with Bide-a-Wee a common name, snobbishly mocked, given to cheap bungalows at down-market English seaside resorts to which lower-middle-class people might retire after a working life as a bank-teller, clerk in a town hall, supervisor in a small workshop, station-master on a small railroad, etc. This would be an immediate association to English readers of the 1940s, or to anyone of my generation.

I wanted to smack myself for forgetting, or neglecting, Frederick’s summer palace, but that other stuff? I had no idea. And that is extremely distressing to me.

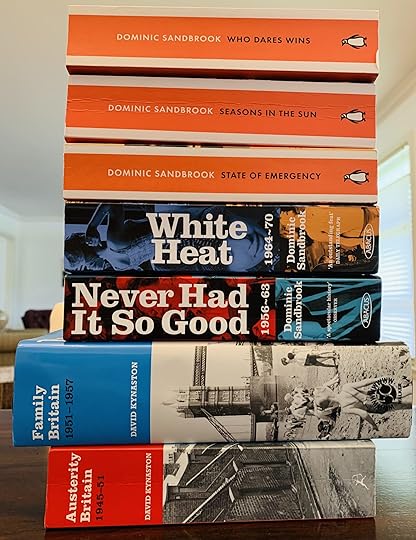

Which leads me to my recently completed summer reading project:

Five thousand nine hundred and seventy-nine pages later, I know so much more than I did about the social history of postwar Britain: random people of brief notoriety, appliances, food products, radio and TV shows, catchphrases etc. etc. The dark question remaining, though, is: How much of it will I be able to remember?

Indeed: Will I even realize, when coming across an item unfamiliar to me, that I could look it up in these books? I am often haunted by a shrewd point C. S. Lewis makes in his Studies in Words: sometimes words change their meanings in ways that don’t call themselves to our attention. Using the current meanings of those words, we can make sense of old sentences — just not the sense that the authors intended, or that readers of their era would have readily identified.

Still, I am making progress, and Sandbrook’s books, while perhaps less scholarly than Kynaston’s in some respects, are wonderfully well-written and perfectly paced. They were a joy to read.

There’s one more problem, though. Sandbrook’s project is ongoing — he wants to keep drawing closer to the present day. But …

The first book in the series appeared in 2005 and covers seven years in 892 pages; The second book in the series appeared in 2006 and covers six years in 954 pages;The third book in the series appeared in 2010 and covers four years in 755 pages;The fourth book in the series appeared in 2012 and covers five years in 970 pages;The fifth book in the series appeared in 2019 and covers three years in 940 pages.At that rate of progression I will be long dead by the time Sandbrook gets to Tony Blair.

August 1, 2021

An Italian born in Texas named Jacobs has just won an Oly...

An Italian born in Texas named Jacobs has just won an Olympic gold medal … this Italophile Texan named Jacobs is verklempt.

July 31, 2021

open letter from a distinguished surgeon

I confess to experiencing not merely disquiet but also exhaustion, in the face of endless demands that I, a trained and experienced surgeon, wash my hands before operating on patients. The chief impetus for these demands seems to arise from one Miss Nightingale, an admirable woman no doubt but one trained neither as a surgeon nor as a physician. Nothing in my extensive experience — as, may I repeat, a highly trained surgeon — indicates the need for such a practice. It is true of course that not all of my patients have survived the operating theatre, but no surgeon has ever had a perfect record of success, and I have good reason to believe that Miss Nightingale in the Crimea manifested no spectacular powers of healing.

Moreover, we do not fully understand the chemical properties of soap; it may well be — indeed I suspect that this is the case — that the introduction of soap-suds, or even hands that have recently been in contact with soap-suds, to the human form will induce more symptoms in an infected or otherwise diseased part of the body than it could possibly ameliorate. In these cases the natural condition of the surgeon’s hands is surely safer than the introduction of a substance as thoroughly unnatural as soap. Indeed, two distant relations of mine have recently written to inform me that they have with their own eyes seen human skin terribly burned, and organs of the human body discolored and withered, in response to contact with soap. Testimony so compelling cannot possibly be dismissed.

I am further concerned by the prolonged and highly agitated statements from her Majesty’s Government on this subject. However well-meaning these public servants may be, their record of — let me speak frankly — incompetence in other matters disinclines me to heed their pleas in this case. Indeed it seems likely that their entire campaign on behalf of hand-washing is prompted by a desire to create a political triumph over the Loyal Opposition, who until recently blessed us all with their wise governance.

In conclusion, and in brief, let me simply say to Miss Nightingale and others who agitate so shrilly on behalf of the strange practice of hand-washing: These are my hands, and whether to wash them or no is my choice.

Your ob’t servant, &c. &c.

good

Sarah Perry is trying to be good: she trained as a vaccinator, sought to help. But being good is hard, and there is a lot of anger about.

This is not to say that we should simply abdicate – toss away the mask, fill our homes with plastic – only to warn against resting easy in our own virtue, assuming malignancy and folly on the part of others. Recently, it has seemed to me that nothing said or done is personal: it is all abstract, representational, showing the colours of a fixed character and tribe. So a man, once wrong, is wrong for ever. He cannot apologise and alter, since that would be nothing but hypocrisy, and he must remain always beyond redemption. This assumption of bad faith has poisoned the public discourse, and caused such deep entrenchment of opposed positions that nobody can hope to see the land. A trench is a comfortable place when the battle’s on, bolstered about by those assuring us of our virtue, and agreeing the unseen enemy is incomprehensibly wicked – certainly I prefer it myself. To take a wider view – to sit, as they say, up on a high horse – is troubling, because here we see the territory, and not the map. From such a vantage we may find our own motives are ignoble, or our position not as wise as we thought, and are available to be shot at from all points. This is a position demanding a kind of subtlety that risks endearing you to nobody – yes, you may say, it is deplorable to protect the economy above lives, but then again a severe and lasting depression may be counted not in pounds and pence, but in vertiginous rises in homelessness, drug dependence, sickness and suicide. Certainly, this is not the flu, but there may come a time when it is something like it; yes, we have to learn to live with it, and there is no life without the risk of death, but living with it may consist of universal basic income, and affordable housing, and so on. Who’d risk expulsion from the trench with these slow negotiations? I blame no one for preferring the sandbags.

July 29, 2021

On Not Reading the Bible

The title of this post is the title of a book I have, for about twenty years now, thought of writing. My thesis would simply be this: We can do almost anything with the Bible except read it.

It is also true that the Bible, especially the Old Testament, tends to resist interpretation — Erich Auerbach famously illustrates this in his discourse on the story of the binding of Isaac in the first chapter of Mimesis — but that’s not what I am talking about here. But I haven’t yet written the book because I find it difficult to explain precisely what I am talking about.

The Bible has a distinctively protean character; it’s a shape-shifter. That is the result, I think, of its being a book that is also a set of books (books that are themselves often stitched together in peculiar ways). Faced with this shape-shifting, we have a tendency to stand away from it to try to see it whole — at the cost of rendering the details invisible — or to zoom in on the details in a way that causes us to lose sight of the greater narrative arc. The former tendency produces books like Northrop Frye’s The Great Code; the latter tendency leads to people receiving Bible verses as text messages.

I think readers of the Bible are always pulled in both of these directions. We may think that in our moment — the moment of text-messaging and the child of text-messaging, Twitter — we are especially prone to fragmenting the biblical text, but let’s recall that when the Bible was first divided into verses — by Robert Estienne in the mid-16th century — one of the most popular books in Europe was Erasmus’s Adagia. Adages or proverbs then, texts now — the impulse to reduction and condensation is the same.

I don’t think we can address this difficulty by assuming and maintaining some kind of ideal middle distance. That proposed solution arises from the twin assumptions that the protean character of Scripture can and should be arrested. But what if neither of those assumptions is correct? What if the only way genuinely to read Scripture is to engage in a constant zooming in and zooming out?

This model of reading resembles the famous “hermeneutic circle” — understanding the whole in terms of the parts and the parts in terms of (our assumptions about) the whole — but reading and interpretation are not the same thing, even if they are often related.

Heidegger’s famous essay “On the Origin of the Work of Art” — an essay he revised repeatedly, which should tell us something about both the importance and difficulty of the issues involved — describes a version of the hermeneutic circle. In this case, though, he is not discussing the relationship between part and whole but between a work of art and the very concept of “art.”

What art is we should be able to gather from the work. What the work is we can only find out from the nature of art. It is easy to see that we are moving in a circle. The usual understanding demands that this circle be avoided as an offense against logic. It is said that what art is may be gathered from a comparative study of available artworks. But how can we be certain that such a study is really based on artworks unless we know beforehand what art is? Yet the nature of art can as little be derived from higher concepts as from a collection of characteristics of existing artworks. For such a derivation, too, already has in view just those determinations which are sufficient to ensure that what we are offering as works of art are what we already take to be such. The collecting of characteristics from what exists, however, and the derivation from fundamental principles are impossible in exactly the same way and, where practiced, are a self-delusion.

So we must move in a circle. This is neither ad hoc nor deficient. To enter upon this path is the strength, and to remain on it the feast of thought — assuming that thinking is a craft. Not only is the main step from work to art, like the step from art to work, a circle, but every individual step that we attempt circles within this circle.

I want to think about this passage and return to it later, because I believe it has implications not just for understanding what art is, not just for clarifying the nature of interpretation, but for helping us to read, even read the Bible.

the fault

This is prompted largely by Robin Sloan’s comments on comments.

A decade ago I was active on Twitter, Tumblr, and Pinboard, and wrote a couple of comment-inviting blogs on magazine websites. Now?

No TwitterNo TumblrPinboard bookmarks are set to privateI blog on my own site, and have comments disabledI’m on micro.blog but only post photosWhat happened? In a nutshell: I simply got tired of strangers wanting to argue with me. (Also, it was moronic to be that Extremely Online. I don’t know how I got anything else done.) Twitter was, you know, Twitter. Blog comments were generally what one would expect from blog comments, occasionally useful but prone to degenerate into spats. People who followed my Tumblr would write — you couldn’t disable such on-site messaging — to chastise me for signal-boosting something I had just quote-posted. People would email similar chastisements about something I had saved on Pinboard, apparently under the assumption that a bookmark is an endorsement.

Even when I moved to micro.blog, where folks are in general extremely nice, I had to stop posting anything but photos because strangers would invariably show up wanting to argue with me about … well, anything. As though the subject doesn’t matter so much as the act of arguing. I don’t know whether such people feel that argument is a means of sharpening their ideas or whether they just want to be heard, but I keep thinking, Man, does everything have to be subject to disputation? Can I not just put something out there for people to take or leave? Even now that I am blogging without comments, I regularly get emails about my posts, and at least 90% of them are negative. It wears on you after a while. (I continue to believe in the intrinsic value of the blog garden, so the negativity isn’t keeping me away.)

The reigning assumption seems to be that every posted opinion or preference or experience or plain old link is an invitation to debate or refute — that’s what social media, to many people, fundamentally is for: debate and refutation. And as long as that is the reigning assumption, then no platform, it seems to me, can be fundamentally different than all of our other platforms. The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our platforms, but in ourselves, that we are disputatious.

July 28, 2021

beats me

Over the past ten days I’ve been thinking a good deal about my friend Michael Brendan Dougherty’s essay on responding to vaccine skeptics.

One key claim Michael makes is that “most vaccine skepticism, if by that we mean reluctance, is not based on conspiracy theorizing — it’s based on risk-benefit calculations.” I wonder if that’s true, and how we might know. All I can go by, in the absence of data, is my own experience, and certain elements of my experience with anti-vaxxers are absolutely uniform. Without exception, they tell me that

The covid pandemic may not be totally made-up, but its dangers are wildly and dramatically overstated by the mainstream media and liberal politicians;Covid is no worse than the flu;Masking doesn’t help;Vaccines don’t work;Vaccines are killing more people than covid has.That covers the substantive issues. But two other elements of my encounters with anti-vaxxers are uniform and, I think, significant:

They are openly and intensely angry;They declaim their beliefs like people reciting a creed, never — and I mean never — asking what my views are or even giving me a chance to state those views should I want to.Everything about their self-presentation militates against dialogue. So for me the question is not “How might I convince them?” but rather “What am I supposed to do if conversation between citizens is not even one of the options on the table?”

For the last forty years I have been interested in our common life in this country, in the ways we live together, and whenever we have experienced pronounced social tension I have had ideas for resolving or at least lessening those tensions. Those ideas have typically been uncommon ones, and I have rarely been under any illusions about the likelihood of their being adopted; but I have nonetheless believed in their likely efficacy. In our current situation I have no idea what to do. I have no tactical suggestions. None. I am totally and absolutely at a loss.

UPDATE: Relatedly, I think, this recent speech by Donald Trump:

No more windows in buildings because environment. I always did great with these buildings that the bigger the window, the better I did, the bigger those windows, I wanted floor to ceiling windows, but they say you can’t do that anymore. We don’t want any more windows. It’s going to be real hard to sell apartments, I think. We have a beautiful apartment, and for environmental reasons, we have not put windows in the building. Oh great. Well, that sounds good. These people are crazy. Whatever happened to cows, remember they were going to get rid of all the cows? They stopped that, people didn’t like that. Remember? You know why they were going to get rid of all the cows? People will be next. People will be in there.

Tens of millions of Americans hear this man speak and think: He will make America great again. In him we place our full trust. In response to this also, I am totally and absolutely at a loss. I don’t even know where to begin.

So I’ll just talk about other things. Snakes & Ladders will now return to its regular programming — and I’m resuming the newsletter next week!

separate … but equal?

I don’t want to see politicians get involved in what should and should not be taught. I would like to see parents speak to teachers and administrators when CRT is creating a bad classroom atmosphere. I would like to see teachers and administrators resist the urge to be defensive and resentful toward criticism of CRT.

But I worry that civil discourse around CRT is not going to happen. Instead, parents who most believe in civil discourse will simply pull their children out of public schools, rather than wade into the controversy. Teachers who are not “woke” will be treated as pariahs by other teachers and administrators. Public schools will end up serving the children of parents who are either very progressive or apathetic. There will emerge another school system, a separate but equal school system if you will, for children of parents who are conservatives or old-fashioned liberals.

two questions

After reading Elizabeth Bruenig’s remarkable article on a recent contretemps at Yale Law School — and after resisting the temptation to immediately take a shower and scrub myself clean — I found myself meditating on two questions:

Did the person Bruenig calls the Archivist believe that by devoting countless hours to investigating and prosecuting two of his classmates he was setting himself up for a high-powered, brilliant career?If so, was he right?Alan Jacobs's Blog

- Alan Jacobs's profile

- 529 followers