Alan Jacobs's Blog, page 158

August 19, 2021

two quotations on innovation and influence

Facebook is full of ugly memes and boring groups, ignorant arguments, sensational clickbait, products no one wants, and vestigial features no one cares about. And yet the people most alarmed about Facebook’s negative influence are those who complain the most about how bad a product Facebook is. The question is: Why do disinformation workers think they are the only ones who have noticed that Facebook stinks? Why should we suppose the rest of the world has been hypnotized by it? Why have we been so eager to accept Silicon Valley’s story about how easy we are to manipulate?

Within the knowledge-making professions there are some sympathetic structural explanations. Social scientists get funding for research projects that might show up in the news. Think tanks want to study quantifiable policy problems. Journalists strive to expose powerful hypocrites and create “impact.” Indeed, the tech platforms are so inept and so easily caught violating their own rules about verboten information that a generation of ambitious reporters has found an inexhaustible vein of hypocrisy through stories about disinformation leading to moderation. As a matter of policy, it’s much easier to focus on an adjustable algorithm than entrenched social conditions.

I find it bizarre that the world has decided that consumer internet is the highest form of technology. It’s not obvious to me that apps like WeChat, Facebook, or Snap are doing the most important work pushing forward our technologically-accelerating civilization. To me, it’s entirely plausible that Facebook and Tencent might be net-negative for technological developments. The apps they develop offer fun, productivity-dragging distractions; and the companies pull smart kids from R&D-intensive fields like materials science or semiconductor manufacturing, into ad optimization and game development.

The internet companies in San Francisco and Beijing are highly skilled at business model innovation and leveraging network effects, not necessarily R&D and the creation of new IP. (That’s why, I think, that the companies in Beijing work so hard. Since no one has any real, defensible IP, the only path to success is to brutally outwork the competition.) I wish we would drop the notion that China is leading in technology because it has a vibrant consumer internet. A large population of people who play games, buy household goods online, and order food delivery does not make a country a technological or scientific leader.

This juxtaposition offers much to reflect on, but one brief comment: The idea that Silicon Valley is meaningfully innovative and the idea that Silicon Valley shapes our social order are the products of the same PR machine, and so perhaps should be subjected to what Con Law calls “strict scrutiny.” As Wang often points out in his fascinating analytical work, one of the biggest differences between China and the USA is that China thinks technologies made of Atoms are more important, and more worthy of major investment, than technologies made of Bits.

I am not in any way rescinding, or even questioning, my long-held view that Facebook is evil and should be destroyed. But if Bernstein is right, then Facebook is more of a symptom than a cause of our social afflictions, and we are even more screwed than I have thought we are.

August 18, 2021

Permanent Crisis

Paul Reitter and Chad Wellmon’s Permanent Crisis: The Humanities in a Disenchanted Age will be on sale tomorrow, and it’s an absolutely essential book for anyone who cares about the humanities — or even just thinks about the humanities. You may read the introduction (as a PDF) here, and also read an interview with Paul and Chad here. I expect to have more to say about the book later, but just for now I want to make a couple of introductory points about what I consider to be the two chief themes of the book — themes woven together skillfully in the development of the argument.

The first key theme is obvious from the title: It is the nature of the modern humanities to be always in crisis. From the Introduction:

One of our chief claims is that the self-understanding of the modern humanities didn’t merely take shape in response to a perceived crisis; it also made crisis a core part of the project of the humanities. The humanities came into their own in late nineteenth-century Germany by being framed as, in effect, a privileged resource for resolving perceived crises of meaning and value that threatened other cultural or social goods as well. The perception of crisis, whether or not widely shared, can focus attention and provide purpose. In the case of the humanities, the sense of crisis has afforded coherence amid shifts in methods and theories and social and institutional transformations. Whether or not they are fully aware of it, for politically progressive and conservative scholars alike, crisis has played a crucial role in grounding the idea that the humanities have a special mission. Part of the story of why the modern humanities are always in crisis is that we have needed them to be.

I don’t think you could read this book with any care and come away doubting the truth of this claim. The second major claim I want to call attention to may seem at first to be rather different, but in fact is closely related to the first. From Chapter Seven:

For decades, the humanities have arrogated to themselves critique and critical thinking, and thus they asserted a privileged capacity to demystify, unmask, reveal, and, ultimately, liberate the human from history, nature, or other humans. Whether as Judith Butler’s high-theory posthumanism or Stephen Greenblatt’s historicist communion with the dead, the humanities have claimed sole possession of critique and cast themselves as custodians of human value. In order to legitimize such claims and such a self-understanding, the modern humanities needed the “disenchantment of the world” and needed as well to hold the sciences responsible for this moral catastrophe. Only then could their defenders position themselves as the final guardians of meaning, value, and human being.

The success of the sciences — and more particularly, I would say, of the technocracy that arose from the explosion of scientific knowledge over the past two hundred years — provides the entire context for understanding the character of the modern humanities: the account of the virtues and goods the humanities claim to be the unique guardians of, and the account of their guardianship as being under constant existential threat.

But this raises a crucial and uncomfortable question: Can the humanities relinquish their crisis narrative without also relinquishing their unique guardianship of humane values such as “critical thinking”? We could scarcely envy a model of humanistic learning that wasn’t in crisis only because, like Othello, it’s occupation’s gone.

In the interview linked to above, Len Gutkin asks whether the humanities can get along without a crisis narrative, and Reitter replies: “Can the humanities do without crisis talk? Probably not, unless there was some massive reorganization of society where there didn’t seem to be a fundamental tension between the pace of capitalism and the pace of humanistic thinking.” This is perhaps more bluntly pessimistic than the book itself, which tries in its Conclusion to suggest some resources that could lead to a Better Way, notably (a) Edward Said’s reading of Erich Auerbach and (b) Max Weber’s Wissenschaft als Beruf — which Reitter and Wellmon have recently edited, in a new translation by Damion Searls.

I’d like to make another suggestion, based on a theme Reitter and Wellmon contemplate early in Permanent Crisis but don’t pursue at the book’s end:

Recent efforts among scholars to establish the history of humanities as a distinct field started with a question: “How did the humanities develop from the artes liberales, via the studia humanitatis, to modern disciplines?” Our question is slightly different: Have the continuities linking the humanist scholarship of the faraway past to that of today been stretched thin? Or have they, or some of them, remained robust? These are, of course, big questions, and we won’t treat them comprehensively, let alone try to resolve them. But we do begin with the premise that the continuities between the modern, university-based disciplines collectively known as the humanities and earlier forms of humanist knowledge such as the studia humanitatis have been exaggerated. The modern humanities are not the products of an unbroken tradition reaching back to the Renaissance and, ultimately, to Greek and Roman antiquity.

I think this is correct. But I also think Reitter and Wellmon are correct when they write, elsewhere in the book, “The current institutional arrangement of university-based knowledge — with its particular norms, practices, ideals, and virtues — was not necessary; it could have been otherwise.”

So here’s what I’m getting at: It may well be that the humanities are chained permanently to their crisis narrative as long as they function within “the current institutional arrangement of university-based knowledge.” That is: If we do not get the kind of “massive reorganization of society” that Reitter mentions, it’s likely that the humanities can only have a self-understanding not dependent on a crisis narrative if they learn to operate outside the structures of the modern research university. And if that were to happen, then the old ways of the studia humanitatis might turn out to be more relevant than they have been in the past several centuries.

thinking and rationality

Reading this Joshua Rothman piece about rationality, I finally realized how my account in How to Think differs most significantly from the models of thinking advocated by the “rationalist community.” The chief difference is this: they proceed by excision, and I proceed by inclusion. Rationalists focus on clearing away those contents of the mind that they believe to be impediments: they’re about “overcoming bias,” about eliminating subjectivity – cognitive errors to them are always about unwarranted intrusions into the rational process. They operate under the (as far as I can tell unacknowledged and undefended) assumption that if you strip away everything that is not rationality as they define it — like the sculptor carving away everything that doesn’t look like an elephant — then you will be able to reach more reliable conclusions about what is true or what you should do.

I don’t believe in that story. Charles Taylor talks about metaphysical “subtraction stories,” that is, accounts of the role of religious belief that assume that if you subtract religion from the human mind and human experience then what will be left is Reason. The rationalist community tells the same subtraction story, though extending the content of what’s to be subtracted from “religion” to “irrationality” of all kinds; it just doesn’t seem to know that that’s what it’s doing. And it doesn’t seem aware of the possibility that taking away bad things does not necessarily leave behind good things. It might be rather that good things need to be built up.

My approach to thinking does not involve excision but rather inclusion: addition and amplification. I don’t believe in getting rid of biases, but rather trying to understand, as Gadamer put it, which of my biases and prejudices are conducive to knowing what’s true and good and which ones impede or disable me from knowing what’s true and good. After all, some of my prejudices are true. Why is that? I don’t think of my emotional responses as violations of objectivity to be eliminated, but rather additional factors to consider in trying to assess whether I’m growing closer to the truth or moving farther away from it. My biases and prejudices and feelings sometimes lead me in the right direction. Why is that? For me, excellent thinking does not require me to strip away portions of my humanity but rather to bring all my resources to bear on the quest for truth and right action — and therefore requires me to enhance my emotional life as well as my purely ratiocinative abilities.

Rothman’s essay is critical not of reason itself but rather of the rationalist movement in some useful ways. He points out that “talking like a rationalist doesn’t make you one,” and sympathizes with Tyler Cowan’s view that “the rationality movement has adopted an ‘extremely culturally specific way of viewing the world.’” As Rothman rightly concludes, “It’s the culture, more or less, of winning arguments in Web forums.”

But there’s something odd about his conclusion, which goes like this:

The realities of rationality are humbling. Know things; want things; use what you know to get what you want. It sounds like a simple formula. But, in truth, it maps out a series of escalating challenges. In search of facts, we must make do with probabilities. Unable to know it all for ourselves, we must rely on others who care enough to know. We must act while we are still uncertain, and we must act in time — sometimes individually, but often together. For all this to happen, rationality is necessary, but not sufficient. Thinking straight is just part of the work.

Isn’t relying on others, if they are reliable others, one of the forms of “thinking straight”? This is a major theme of How to Think: the wisdom of knowing your own limits, and the necessity of, instead of always trying to “think for yourself,” finding trustworthy people to think with. It’s odd that Rothman seems to have absorbed an account in which doing this is something other than rationality, something other than thinking straight.

August 17, 2021

A random note: early in Shakespeare’s Henry V, the Archbi...

A random note: early in Shakespeare’s Henry V, the Archbishop of Canterbury constructs an elaborate simile comparing human society to a colony of honeybees, and speaks of “the singing masons building roofs of gold.” Two things struck me as I read that line: it’s one of the most gorgeous lines of verse I have ever read, and nobody but Shakespeare would have written it. The singing masons building roofs of gold.

departments of knowledge

Every department of Knowledge we see excellent and calculated towards a great whole. I am so convinced of this, that I am glad at not having given away my medical Books, which I shall again look over to keep alive the little I know thitherwards…. An extensive knowledge is needful to thinking people — it takes away the heat and fever; and helps, by widening speculation, to ease the Burden of the Mystery: a thing I begin to understand a little, and which weighed upon you in the most gloomy and true sentence in your Letter. The difference of high Sensations with and without knowledge appears to me this — in the latter case we are falling continually ten thousand fathoms deep and being blown up again without wings and with all the horror of a bare shouldered creature — in the former case, our shoulders are fledge, and we go thro’ the same air and space without fear.

— Keats, letter to John Hamilton Reynolds (3 May 1818), making a very similar case to the one I make in Breaking Bread with the Dead. Pynchon: “Personal density is proportionate to temporal bandwidth,” and in this case intellectual bandwidth — the breadth of understanding that comes from having some understanding of very different disciplines. Keats loved poetry as much as anyone ever has, maybe more than anyone ever has, but he didn’t want to forget his medical training. The more knowledge he has the less susceptible he is to the “heat and fever” of the moment.

August 16, 2021

Tolkien and Auden

J. R. R. Tolkien and his wife Edith with their grandson Simon, at their home on Sandfield Road, Oxford, 1966. Photo from the Oxford Mail.

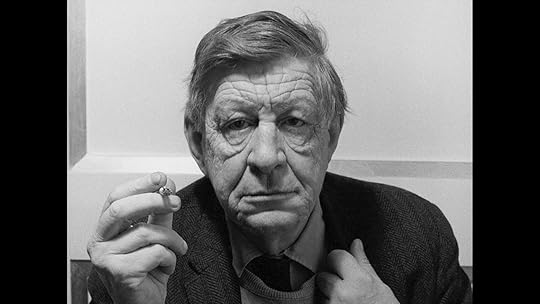

Tolkien was not an easy man to be friends with, as he himself knew. But relatively late in his life he became friends with the poet W. H. Auden, thanks to Auden’s reviews in the New York Times of the first and third volumes of The Lord of the Rings. Those came at a moment when the success of LOTR was by no means assured, and indeed those who hated the book — most notably Edmund Wilson — made a point of including Auden in their denigration. There were moments of tension later on, most notably when a London newspaper quoted Auden as having said that the decor of Tolkien’s home was “hideous”; and Tolkien — so it seems to me anyway — was never fully at ease with non-Catholics. But in the main the friendship remained firm, if rather distant, and was a source of pleasure and comfort to both men. When some medievalists produced a festschrift for Tolkien on the occasion of his seventieth birthday, Auden contributed “A Short Ode to a Philologist”; and when Auden received a sixtieth birthday festschrift in the journal Shenandoah, Tolkien offered a lovely tribute, “For W.H.A.,” in both Anglo-Saxon and modern English.

You can read about their relationship in the biographies that Humphrey Carpenter wrote about each man, and also in Tolkien’s letters. But it seems to me that the relationship is interesting enough that it deserves some kind of artful presentation; perhaps one that portrays their friendship as more intimate than it really was. And I have always been haunted by the fact that, though Tolkien was fifteen years older than Auden, they died within a few weeks of each other: Tolkien in Bournemouth on September 2, 1973, and Auden in Vienna on September 29.

So I wrote a short play about them.

There I imagine a conversation between them — taking place probably in 1967, though don’t try to pin me down about that — a conversation based on things they actually said to each other, usually in letters, and things they said or wrote on matters of mutual interest. That is, Auden really did invent a parlor game called Purgatory Mates, and Tolkien really did say that Auden’s proposal to write a book about him was “an impertinence.” Auden’s final words in the play are based on an encounter he had with the young Jay Parini. And so on. So, the play is Based on True Events and Words, even though I seriously doubt that they ever would have had a face-to-face conversation like this. Auden had become by this point in his life too garrulous, and Tolkien too mumblingly reticent. (In both cases excessive alcohol consumption played a part.) So I had to make Auden more shortly-spoken than he was in real life, and Tolkien more articulate.

Anyway, it’s probably really terrible, but I enjoyed writing it. It scratched an itch.

August 13, 2021

Orbanistas

[I had here an Andrew Sullivan quote about the recent right-wing fascination with Viktor Orban and Hungary, but while I agree wholly with Andrew’s views, the matter deserves more than a quotation. I hope to spell out my thinking in more detail later.]

Okay, I’m back.

When I read the writings of the current enthusiasts for Viktor Orban, the first thing I note is how evasive they are. They won’t quite exonerate Orban. They admit that he’s “not perfect” — as though that’s a significant concession — but in each particular case his authoritarian decisions are either justified or dismissed as insignificant. Any sort of positive vision is hard to find. The evasiveness brings to mind the comfortable British Marxist in Orwell’s “Politics and the English Language” who doesn’t dare say “I believe in killing off your opponents when you can get good results by doing so” and so, instead, says,

While freely conceding that the Soviet regime exhibits certain features which the humanitarian may be inclined to deplore, we must, I think, agree that a certain curtailment of the right to political opposition is an unavoidable concomitant of transitional periods, and that the rigors which the Russian people have been called upon to undergo have been amply justified in the sphere of concrete achievement.

Of course, Orban isn’t a mass murderer, only a would-be tyrant. But if you take that sentence and substitute “Orban” for “Soviet” and “Hungarian” for “Russian,” you have a neat summary of the characteristic rhetorical approach of the Orbanistas.

Orwell famously says that “the great enemy of clear language is insincerity,” but I don’t think insincerity is the problem with the Orbanistas. The problem is that critics keep wondering about policies and the Orbanistas don’t care about policies. What they care about is hating the right people. They get impatient if you point out to them Hungary’s poverty, or its exceptionally low level of religious observance, or its unfree press, or the high numbers of young Hungarians fleeing the country, not because they think those developments are good, but because they find them insignificant in comparison to the great virtue of effectual hatred. (Donald Trump’s problem, in this light, is simply the ineffectuality of his hatreds.)

In a thoughtful essay, John Gray describes the work of Eugene Lyons, who wrote in Assignment in Utopia (1937) about the three major types of Western admirers of the Soviet experiment:

Those who have a “professional” interest in being on good terms with the regime (Walter Duranty of the New York Times being the most famous of these); Those for whom association with the regime offers the opportunity to display their wit and intelligence, to épater le bourgeois; The “useful idiots,” who suffer from a kind of motivated blindness: according to Lyons, “they were deeply disturbed by the shattered economic and social orthodoxies in which they were raised; if they lost their compensating faith in Russia life would become too bleak to endure.”I think this is a useful taxonomy to apply to the Orbanistas also. There are clearly some in each camp.

[I had here an Andrew Sullivan quote about the recent rig...

[I had here an Andrew Sullivan quote about the recent right-wing fascination with Viktor Orban and Hungary, but while I agree wholly with Andrew’s views, the matter deserves more than a quotation. I hope to spell out my thinking in more detail later.]

assessment

Brentford 2-0 Arsenal: A fair result, accurately reflecting the quality of the two sides and their management.

caricatures

We enjoy caricatures of our friends because we do not want to think of their changing, above all, of their dying; we enjoy caricatures of our enemies because we do not want to consider the possibility of their having a change of heart so that we would have to forgive them.

— W. H. Auden

Alan Jacobs's Blog

- Alan Jacobs's profile

- 529 followers