Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 9

December 3, 2024

Capitalist Pigs: “Okja “

When I sat down to watch Okja,I knew only that this was a recent Korean film, highlighting the warmrelationship between a young girl and a supersized CGI pig. My guess was thatthe film would have something of an ET vibe, featuring tenderness,innocence, and a certain amount of whimsy. And, to be honest, these elementscan all be found in Okja. But it didn’t at first occur to me that anyfilm written and directed by Bong Joon-ho—who followed up Okja with 2019’slacerating Oscar-winner, Parasite—would doubtless be well laced withblack humor.

I also didn’t realize atfirst that Okja is a true East-meets-West collaboration between Bong andHollywood, with Netflix and Brad Pitt’s adventuresome Plan B Entertainment muchinvolved. A good part of the story takes place in New York City, and key rolesare played by box-office favorites Tilda Swinton, Paul Dano, and JakeGyllenhaal. Gyllenhaal’s role as the sell-out host of a TV animal show ishilarious, though I found him absolutely unrecognizable, even after I saw hisname in the end-credits. As for Swinton, she takes her usual perverse delightin playing a character who’s obnoxious in the extreme. Her role is that of acorporation head who has nothing good to say about her father (an investor inNapalm) and her sister (under whose company leadership a lake exploded). Shecoos to her team about her own development of adorable super-pigs, whose meatwill be (among other good things) inexpensive and environmentally friendly. Ofcourse she’s lying through her teeth, and Giancarlo Esposito (of BreakingBad fame) is on hand to help take things from bad to worse.

But these aren’t the onlyquestionable characters in Okja. When the super-pig she’s helped toraise in the mountains of Korea is summoned to New York (supposedly to becrowned as top pig in a competition arranged by Swinton’s company), young Mijacan’t prevent her beloved pet from being taken from her. But she finds she hassome unlikely allies, members of the Animal Liberation Front, who’ll do justabout anything to protect animals from human exploitation. Led by the (usually)soft-spoken Paul Dano, they at first come across as earnest and reasonable, buttheir passion for their cause leads them, at times, into outrageous acts. Theirintentions may be good, but often they seem as crazy as the greedy capitaliststhey oppose with single-minded zeal.

So what becomes of the younggirl and the giant pig? I don’t thinkit’s giving too much away to say that in this film everyone ultimately getswhat he or she deserves. Though there are some stomach-churning moments thatspell out the ultimate fate of most of those giant pigs, our two favoritecharacters live to enjoy another, brighter day.

Okja had its world premiere in 2017 at the Cannes FilmFestival. Despite some technical difficulties during the screening, it wasrewarded with a four-minute standing ovation, and was nominated for theprestigious Palme d’Or. Filmed in Korean and English, the film makes adeliberate mistranslation (by Korean-American actor Steven Yeun, playing one ofthe ALF activists) an essential part of its plot.

By the way, anyone checkingout the recent DVD (which boasts a separate disc full of extras about thefilm’s technical challenges) should be sure to keep watching until the veryend. Following a long set of end-credits, there’s a sardonic coda featuring there-united ALF team. It’s as though Bong can’t bear to end his film on a note ofHappily Ever After.

November 28, 2024

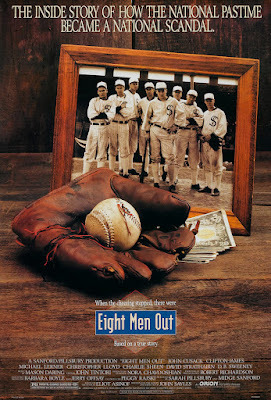

Say It Ain’t So, Joe! John Sayles’ “Eight Men Out”

Baseball is America’s game. That’sits reputation, anyway—as a wholesome family entertainment in which athletes faceoff against one another at a sporting event that’s easy to watch and enjoy.

The fact that the players’faces aren’t covered is one reason that baseball seems to be the favorite teamsport of moviemakers. So’s the basic set-up of the game. There’s no scrum ofheavily padded guys smashing into another clump of players, similarlyoutfitted, with the spectator desperately trying to locate the pigskin andfigure out who is who. Instead, in baseball, one solitary soul on the pitcher’smound rhythmically faces down one batsman at a time. A man with a ball versus aman with a bat: what could simpler or more dramatic?

That’s got to be at leastpart of the reason why there are so many baseball movies. Some are lively andpure fun, like 1949’s Take Me Out to the Ballgame and 1958’s DamnYankees, both of them star-studded musicals. Some are heartwarming biopicsabout baseball greats, like The Pride of the Yankees (1942, about LouGehrig) and several films focusing on major league baseball’s first Blackplayer, Jackie Robinson. (See 1950’s The Jackie Robinson Story, in whichRobinson played himself, and 2013’s 42, starring Chadwick Boseman.) Baseballtakes on an almost mythic significance in TheNatural (1984), Bull Durham (1988), and Field of Dreams(1985). In the last of these, a young farmer in search of a father figurebuilds his own ballfield and greets the ghostly Shoeless Joe Jackson, alongwith the other disgraced members of the Chicago White Sox, who were banishedfrom the sport forever for their part in fixing the 1919 World Series.

Writer/director John Sayles hasnever much gone in for simple projects. Though his films over the years can besorted into many genres, he seems to particularly appreciate American history,as seen on a broad canvas. In 1987, he won wide critical acclaim for Matewan,the often-brutal story of West Virginia coal miners overcoming obstacles toform a union. One year later, he directed an ensemble of major Hollywood actors(including John Cusack, Michael Lerner, John Mahoney, and Charlie Sheen) in thestory of what is often called the Black Sox Scandal. Eight Men Out detailshow, in an era when betting on baseball games was rampant, members of thepennant-winning Chicago White Sox were approached by mobster types to throw theseries, in exchange for promises of hefty payments. What made Sayles’ screenwritingcomplicated is that, no one, including baseball historians, has the wholestory. We don’t exactly know who-all was in on the fix, nor who agreed, andthen eventually changed his mind. What we DO know is that there were many badguys around, including mobsters, greedy players, and a team owner (CharlesComiskey) so cheap that some players apparently agreed to throw World Seriesgames as a way of getting back at a boss-man who promised them bonuses butnever paid up. And we know that eightplayers were eventually prosecuted, including at least one (Buck Weaver, playedby Cusack) who deplored the idea of playing to lose, but never squealed on histeammates.

Sayles takes it all on: theplayers, the crooks, the management, the sportswriters who smelled a rat. (Hehimself appears as journalist Damon Runyon, and the great Studs Terkel playsanother sportswriter of the day.) Sayles has also got the little urchin wholooks up at his former hero, Shoeless Joe Jackson, and cries out, “Say it ain’tso, Joe.” Very mythic; very moving.

November 26, 2024

The Gregarious, Gorgeous Teri Garr

I once had the good fortuneof seeing Teri Garr up close and personal. It was decades ago, long before thebrilliant comic actress was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, the crueldisease that recently ended her life at age 79. The place: the tiny, crampedlocker room at Jane Fonda’s then-famous West Hollywood exercise studio. Both ofus were changing out of exercise gear. She was among friends, clearly—and I sawher as a true life force, lively and exuberant.

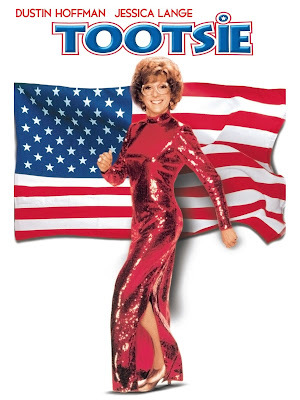

She brought that sameexuberance to her acting career, which included the wife role in CloseEncounters of the Third Kind and the adorable mädchen who loved aroll in the hay in Mel Brooks’ Young Frankenstein. Her biggest screensuccess came in 1982, with the release of Tootsie, in which DustinHoffman stars as an out-of-work actor who disguises himself as a woman to win asoap opera role. The gender confusion that arises in this Sydney Pollack filmis hilarious. But it also seems quite modern, given that there’s a move afootto deny a newly-elected transgender U.S. congresswoman the right to use thewomen’s restroom in the Capitol. (So what, pray tell, is she supposed to dowhen the need arises?)

When Tootsie was beingcast, Garr apparently hankered for the role of the female lead. Julie isdepicted as a slightly damaged but sturdy soul who interacts with Hoffman’sDorothy Michaels in a popular hospital-based soap opera. (She introducesherself to the new cast member as the “hospital slut.”) Julie treasuresDorothy’s friendship and is guided by her relationship wisdom, but has noinkling that this sassy older woman is actually a man—and that he’s in lovewith her. After losing the role of Julie to Jessica Lange, Garr was reluctantto take the smaller part of Sandy, the neurotic would-be actress who’sMichael’s protégée and at one point his accidental lover. (Don’t ask!)Luckily for us, Garr ultimately changed her mind about the role. Sandy’suproarious neediness is a highlight of the film, and resulted in an Oscarnomination for Best Supporting Actress. Ironically, Jessica Lange was alsonominated in this category, and took home the gold statuette: it was the onlywin for Tootsie that evening despite a whooping nine nominations. (Thiswas the year of Gandhi—and the gender-bending Victor/Victoria).But if Lange won the Oscar, Teri Garr completely won my heart.

Like all the greatestcomedies, Tootsie has something to say, about the human condition. Itsparticular focus is on how women are treated in what often continues to feellike a man’s world. What Dustin Hoffman’s character discovers—in thisbeautifully directed, beautifully written, beautifully edited film—is thatwomen benefit from being able to stand up for themselves. And, as a man, hecomes to acknowledge that women need, and deserve, basic respect. Two prominentcharacters who have not learned this lesson are Dabney Coleman as anoutrageously sexist TV director and George Gaynes as a preening actor who makesit his business to tongue-kiss every actress on camera. (By contrast, Julie’sfather, as played by Charles Durning, is a manly but gentle widower who issmitten by “Dorothy” and complicates things by proposing marriage.) Big kudos to screenwriter Larry Gelbart forfinding the funny in the battle of the sexes while acknowledging that hischaracters all have something to learn. One of those characters of course isGarr’s Sandy. But she fights to hold onto her sense of humor. That of coursealso describes Garr, who considered titling her memoir, Does This WheelchairMake Me Look Fat?

November 22, 2024

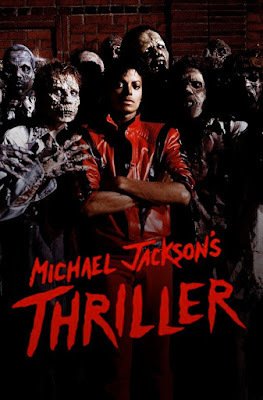

Quincy Jones: Remembering a Thriller

I’ve been waiting for theperfect moment to write a tribute to the late Quincy Jones, music manextraordinaire. Now I think the time has come. On Sunday, daughter RashidaJones accepted the honorary Oscar that was supposed to be handed to her dad atthis year’s Governors Awards ceremony. She was even able to deliver the speechhe’d penned for the occasion: the man was prepared! Always an optimist, Jones celebratedmusic and film as having the power to make “the world a more understanding andembracing place for us all to exist.” (Other honorees included writer/director Richard Curtis—who was warmlyroasted by Hugh Grant—as well as veteran casting director Juliet Taylor, andthe longtime producers of the James Bond films, Barbara Broccoli and Michael J.Wilson.)

It’s hard to write aboutQuincy Jones because, in his 91 years of life, he found success as a recordproducer, composer, arranger, conductor, trumpeter, and bandleader. He alsofunctioned from time to time as a movie producer (the 1985 Spielberg screenadaptation of The Color Purple was one of his projects) and occasionalactor. As an arranger and conductor, he worked closely with greats like FrankSinatra and Count Basie. Hit tunes with which he was involved ranged all theway from Lesley Gore’s “It’s My Party” to the wacky Austin Powers theme music(originally called “Soul Bossa Nova”) to Michael Jackson’s bestselling Thrilleralbum, on which he worked as a record producer.

The artistic period I knowbest is the 1960s, and I’d like to remember Jones in terms of that pivotal decade. He attracted attention for his very firstscore, written for Sidney Lumet’s The Pawnbroker (1964), in which RodSteiger played a Holocaust survivor haunted by his memories. He went on toscore films that were both serious (The Slender Thread) and comic (Walk,Don’t Run). But his first of many banner years was 1967, when he wasinvolved with scores for five films, including Carl Reiner’s Enter Laughing, the thriller Banning,the very dark In Cold Blood, and the year’s top award-winner, In theHeat of the Night. The last of these featured a bluesy Jones-composed titlesong performed by his longtime idol, Ray Charles. Though In the Heat of theNight was nominated for seven Oscars and won five of them (including BestPicture), Jones’ contribution to that film was overlooked by the Academy.Still, in that same year he was honored with two of his seven competitive Oscarnominations, one for the jazzy score of In Cold Blood and one for “TheEyes of Love,” an original song featured in Banning. “The Eyes of Love”made hm the first-ever African American to be nominated by the Oscar voters forBest Original Song. His two Oscar nominations in a single year was alsorecord-breaking for an African American composer.

Ironically, Jones never won acompetitive Oscar. He gained another Best Original Song nomination for a SidneyPoitier romantic comedy, For Love of Ivy, and a decade later his filmscore for The Wiz was also recognized. The Color Purple earnedhim three nominations, including Best Score, Best Song (with Lionel Ritchiealso involved), and Best Picture (he was nominated along with fellow producersSpielberg, Kathleen Kennedy, and Frank Marshall). And the posthumous statuettehe just won was not his first honorary Oscar. Back in 1995 he was given theJean Hersholt Humanitarian Award, the first musician ever to be so honored bythe Academy. (He eloquently called his time on stage to receive that golden trophy“the proudest moment of my life.”)

November 19, 2024

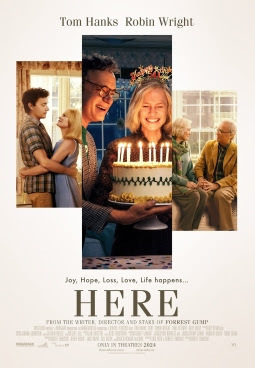

“Here” Today, Gone Tomorrow

I wasn’t at all sure what Iwas going to feel about Tom Hanks’ latest film, directed by Robert Zemeckis andalso featuring Hanks’ Forrest Gump co-star, Robin Wright. Frankly, Heresounded corny, if not downright weird: an entire movie in which the cameranever moves, and the story toggles between various occupants of the very sameplace, from dinosaurs and Native Americans to disparate 20th centuryfamilies living in a large old house. All I could think of, going in, was astage oddity by Thornton Wilder called The Skin of Our Teeth. In it,people representing Adam, Eve, and their kin somehow live both in the Ice Ageand in what was, in 1942, the present day. The central theme? Survival.

Here is based not on The Skin of Our Teeth but on a2014 graphic novel by Richard McGuire, derived from his own comic strip. Clearly,its central topic is Time: how life evolves, personal values change and getoverridden, individuals—no matter howbright or how amiable—can’t stand up to time’s onslaught. It’s a motif thatcertainly has meaning for all of us. Poets have been writing about it forcenturies. Here’s what English poetAndrew Marvell published in 1681: “At myback I always hear/ Time's wingèd chariot hurrying near.” (Marvell, it must besaid, was trying to talk his coy mistress into bed by reminding her that youthfulvigor doesn’t last forever. Yes, things change.)

Zemeckis, who has neverlacked for grand ambitions, seems determined to make a film for the whole humanrace. Certainly, while never moving from one fixed spot, he tries to cover awhole lot of ground. Along with the dinosaurs and Native Americans there arehistorical figures (Benjamin Franklin) and small children and decrepit oldstersand pioneer inventors and nice people who never quite amount to much ofanything. The most recent owners of the house that becomes the film’s entireuniverse are African American. We learn frustratingly little about them, but Ithink they are popped into the story in an attempt to cover all (or, I guess,most) bases when it comes to American history.

But most of the screen timebelongs to the couple played by Hanks and Wright. Through the very latest inde-aging technology, we meet them as young high schoolers in love, with prettyblonde Margaret meeting her beau’s parents, a bitter World War II veteran (an impressive PaulBettany) and his devoted wife. We watch over the years as Richard and Margaretcome to share the house with his ageing father and mother. They celebrate aquickie wedding, then there’s the birth of a daughter; Richard’s frustrationwith his workaday job; Margaret’s chafing at the bonds of matrimony; illnesses andother setbacks, sometimes interrupted by the narrative’s bounce into the livesof other couples with other joys and challenges.

At movie houses, all trailersare carefully selected to match the upcoming flick. It was obvious, when I saw Herethat the multiplex honchos were unclear on what kind of audience would be watching this film. So I saw a terrifyingtrailer about American neo-Nazis, and another about actual Nazis in World WarII. Then there were spots for benign family flicks like Moana 2 and Wicked.Confusing? I, for one, think it’s my own age group that should respond mostthoughtfully to Here. We remember Tom Hanks from movies like Splash andBig, when he was as youthful and lively as his de-aged self in earlyscenes from this film. And so were we.

November 15, 2024

A Star is Born (Again)

Why, exactly, do we lovemovies about the making of movies? Showbiz seems like a glamorous , mysteriousworld that most of us aspire to enter. Many of us nurse private fantasies abouta stardom we know we’ll never achieve, and there’s a perverse comfort indiscovering that show business has its seamy side—and its tragic side—as well.

Curiously, in the early daysof sound movies, most of the showbiz stories on the screen—pictures like BusbyBerkeley’s 42nd Street and Footlight Parade as well aschestnuts like Stage Door—were devoted to the challenge of putting on a theatricalproduction. It was Broadway that seemed most glamorous back then.Berkeley’s famous musical numbers, like the “By a Waterfall” extravaganza from Golddiggersof 1933, contained elements like scantily-clad chorines swimming information, gliding underwater, or sliding down waterfalls into welcominglagoons. Such moments were often shot from above, and the joke was that theycouldn’t possibly work in a Broadway theatre.

Despite moviedom’s ongoingfascination with success on the Broadway stage, the 1930s also saw two popularflicks that chronicle a newcomer’s overnight rise to Hollywood stardom. In1932, George Cukor directed Constance Bennett in What Price Hollywood?, thesaga of a waitress who’s discovered by a film director with a drinking problem.She quickly achieves fame and fortune, while he spirals downward, with romanticcomplications galore. It was briefly popular, though no one pretended it was arealistic look at the film industry. A mere five years later, William Wellmandirected Janet Gaynor and Frederic March in A Star is Born, which isquite similar to What Price Hollywood ? in its plotting, but adds thecomplication that Vicki Lester (née Esther Blodgett) loves and marries her champion,fading actor Norman Maine. The lavish production, which some say mirrored thetroubled marriage of Barbara Stanwyck and Frank Fay, was enormously successful.

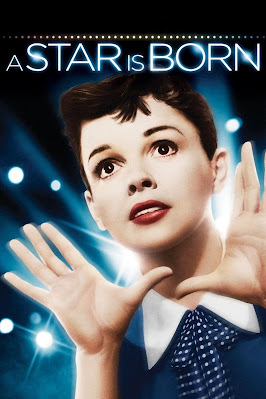

Almost twenty years later, in1954, Cukor took another crack at the material, which was to be his firstmusical and first Technicolor film. This version of A Star is Born showcasesthe powerful singing of Judy Garland, who was looking for a career comeback, aswell as the dissolute complexity of the ageing thespian played by James Mason.(In his George Cukor’s People, film historian Joseph McBride calls thisfilm, despite its studio butchering, Cukor’s very finest effort.) The restored version I’ve just finishedwatching is 178 moments long, and there are some unusual tonal shifts fromcheery musical comedy hijinks to downright tragedy, but this is the version tosee. And hear: Garland belting “The Man That Got Away” is a moment notto be missed. (It was nominated for a Best Song Oscar, but—unthinkably—lost tothe sweet, syrupy “Three Coins in the Fountain”).

Making Esther into a singeropened the door for two further remakes featuring pop legends of the moment.The 1976 film, starring Barbra Streisand and Kris Kristofferson, shifts thefamiliar story to the world of rock ‘n’ roll, adding onscreen sex, a soupçon ofinfidelity, and a really memorable poster. The year 2018 saw Bradley Cooper’s re-imagining of the story, with LadyGaga garnering raves for her first serious acting role.

Who knows when the nextversion will show up? Maybe—why not?—it could involve an older female star andan appealing young male newcomer. After all, there’s nothing that says that thewoman can’t be the knowledgeable veteran of Hollywood. But we asaudience members wouldn’t easily accept that as anything but grotesque. See,after all, Sunset Boulevard.

November 12, 2024

Tallying the Votes: “Conclave”

You’d think that, afterNovember 5, I would have had enough of elections. But there I was, two dayslater, checking out a film that is all about what it takes to get elected. No,I wasn’t watching Reese Witherspoon asTracy Flick doing everything in her power to be chosen student body presidentin Election. (That 1999 flick—both delightful and disturbing—turnedMatthew Broderick of Ferris Bueller fame into a much-beleagueredgrown-up, and established writer/director Alexander Payne as someone to watch.But I digress.)

What I saw last Thursdaynight was not about high school girls in very short skirts, but rather aboutRoman Catholic cardinals in long ones. The brand-new Conclave, based ona popular novel, takes us behind the scenes of the election of a new pope ,after his predecessor is found dead in his Vatican apartment. There’s been nomurder most foul: it’s clear the old man died of natural causes. Both thepublic and the princes of the church are in deep mourning . But life goes on,and a new man must quickly be chosen to wear the so-called Ring of theFisherman, like the one that has just been wrested off of the dead pope’sfinger.

That’s why Roman Catholiccardinals from around the globe are locked in the Sistine Chapel, directlybeneath Michelangelo’s famous frescos, to choose one of their number as theSupreme Pontiff. Each will write a name on a small slip of paper, which will ritualistically be slipped into achalice. An appointed cardinal reads each ballot. Because it takes a two-thirdsmajority to win, multiple rounds of balloting are generally required. Then, atlast, the burned ballots will emit white rather than black smoke, indicating tothose waiting breathlessly outside that a new pope has been chosen.

The film Conclavemakes clear that, amid all the ritual formality of the voting process, there’soften a real power struggle going on. The papal candidates make no speeches andissue no campaign promises, but their views are well known to their fellowcardinals, and factions naturally arise in support of various approaches to theancient institution they all hold dear. Some skullduggery is also to beexpected: the always memorable John Lithgow plays a cardinal who trips up arival by dramatically exposing a long-ago transgression. We meet also a deeplyconservative cardinal who seeks to undo many of the church’s recent reforms, amysterious Mexican cardinal who was elevated in secrecy by the late pope, andStanley Tucci as an American cardinal who’s probably too liberal-minded to bechosen pope. At the very center of the film is Ralph Fiennes as a deeplyscrupulous cardinal faced with the unenviable task of managing the ins and outsof the Holy See. I should not overlook the film’s one important femalecharacter, Isabella Rossellini as Sister Agnes, who sees bad behavior that the cardinalswill not admit to. There’s one point the film makes crystal-clear: everycardinal, no matter how modest his manner, secretly dreams of beingelevated to the papacy, and has long sincepicked out his papal name.

Conclave is directed by Edward Bergerwho won acclaim for last year’s All Quiet on the Western Front. Hebeautifully manages the film’s huge canvas: Conclave is gorgeous to lookat, and is well served by a fascinating score. The acting ensemble provesimpressive, and Fiennes is deservedly getting raves for his complex role. Yes,toward the end the plot twists become increasingly unconvincing, but Conclaveremains a satisfying behind-the-scenes look at a world we’ll never fullyknow.

November 8, 2024

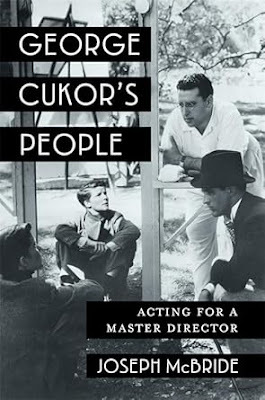

Meeting George Cukor’s People

Many decades ago I wasthrilled to interview film director George Cukor at his home (some called it avilla) in the hills above the Sunset Strip. He was then 80 years old, with along string of hits behind him. After four previous nominations he’d finallywon an Oscar for his lavish, charming screen adaptation of My Fair Lady. Latein life, he’d discovered the challenges of television, and had just finisheddirecting close friend Katharine Hepburn in The Corn is Green. When wespoke, largely about his views on old Hollywood and its star system, he wasunfailingly candid and witty. As he said to end our chat, “Don’t you thinkwe’ve talked an awful lot? I think I’ve done it thin. And I sparkled!”

Back in 1978, I’d seen manyCukor films in theatres and on television, but DVDs and streaming services didnot yet exist. So I went into my quickly-arranged interview without an in-depthknowledge of Cukor’s career as a whole. Happily, I now possess a fascinatingnew book, George Cukor’s People: Acting for a Master Director, whichputs Cukor’s fifty years in Hollywood into perspective. Its author is JosephMcBride, whose credentials make him the perfect choice to see Cukor whole. Joehas been, in the course of his own long career, a film journalist and ascreenwriter. (Like me, he has a Roger Corman connection, and is credited withwriting Rock n’ Roll High School.) He was also a novice but dedicatedactor in Orson Welles’ last film, The Other Side of the Wind. He hastaught film studies at San Francisco State for decades, and his twenty-plusbooks include much-admired studies of Hollywood directors John Ford, FrankCapra, and Billy Wilder. I haven’t read each and every McBride book, but I’mconvinced George Cukor’s People is one of his very best.

McBride avoided writingabout Cukor for many years, because hewasn’t sure how to approach the career of a man whose films covered such a widerange of styles and subjects. Recognizing that Cukor’s close work with actorswas the key to his success, McBride has now chosen to zero in on the way he handledhis stars, drawing out brilliant performances from luminaries ranging from JohnBarrymore (in Dinner at Eight) to Greta Garbo (in Camille) toMaggie Smith (Travels with My Aunt). He also identifies Cukor’s favoritesubjects: dreamers, outsiders, the legend of Pygmalion creating (and thenfalling in love with) Galatea, and life as a performance.

Of the book’s 28 chapters, Iwas perhaps most taken with McBride’s sensitive analysis of Cukor’s contributions in Gone With the Wind before he was fired by David O. Selznick, and with his appreciation for thebrilliant Technicolor work in 1954’s A Star is Born, despite the film’smangling by studio execs. His close analysis of Ingrid Bergman’s Oscar-winning performancein Gaslight (he told her to visita mental institution and study the patients) is memorable as well. And he endswith a tender paean to a TV film I too love: the teaming of a late-in-life Katharine Hepburn and Laurence Olivier in 1975’sscintillating but sweet Love Among the Ruins.

What makes McBride’s work somemorable is that he combines the erudition of a scholar and the savvy of aninsider with the soul of a poet who loves movies. Here’s his take on LoveAmong the Ruins: it “serves as one of the purest expressions of Cukor’scareer-long dedication to the transcendent power of the dreamer and the role ofthe theatre in heightening and improving upon reality.” Beautifully said.

November 5, 2024

Why It Happened One Night (at the Biltmore Hotel in 1935)

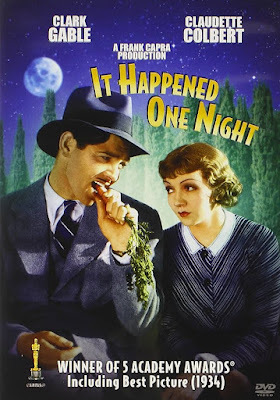

It’s rare that a comedy winsthe Oscar for Best Picture. You wouldn’t think a slight romantic farce about arunaway heiress and a down-and-out newspaperman would stand a chance. Oscarsusually go to intensely dramatic films, especially those linked to majorhistorical events like the Civil War (see Gone With the Wind), World WarII (see Patton, The Bridge on the River Kwai, From Here to Eternity),and Vietnam (The Deer Hunter, Platoon). Social problemmovies like Gentleman’s Agreement and 12 Years a Slave also makefor Oscar bait.

But in 1935 the five topOscar categories (Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actor, Best Actress, BestAdapted Screenplay) were filled by a quickly-made little picture called ItHappened One Night. It wasn’t expected to be a hit. Robert Riskin’s scriptwas turned down by many stars. Claudette Colbert, no fan of director FrankCapra, demanded that she receive twice her usual salary (that is to say$50,000) to play Ellie Andrews, and that shooting be finished in four weeks soshe could go on a planned vacation. Male lead Clark Gable also had his doubtsabout the project. Fortunately, the film was a simple one to shoot (entirely onthe Columbia lot and in the L.A. area), and interaction between Colbert andGable turned out to be comedy gold.

To understand the accoladesfor It Happened One Night, it helps to look back on the Oscar ceremonyfor 1935, only the seventh time that the golden statuettes were presented toHollywood’s finest. The stars and the moguls gathered in the ballroom of L.A.’sBiltmore Hotel to fête the winners. No fewer than 13 nominees vied for bestpicture. I’ll name a few: Flirtation Walk (starring Ruby Keeler and DickPowell in a romantic film about West Point cadets),The Gay Divorcee (anAstaire/Rogers musical), The Thin Man (first in a long series ofcomic mysteries), Viva Villa1 (amuch-fictionalized biography of the Mexican revolutionary starring WallaceBeery). The ultra-serious prestige picture as top vote-getter was somethingHollywood had clearly not yet discovered.

Frank Capra competed withonly two other directors: Victor Schertzinger for One Night of Love andW.S. Van Dyke for The Thin Man. Clark Gable, who beautifully played araffish reporter in It Happened One Night (and changed men’s sartorialhabits overnight when he took off his shirt and revealed a bare chest), viedonly with the always amusing William Powell (The Thin Man) and FrankMorgan, playing an Italian duke in The Affairs of Cellini. Colbert, asthe headstrong heiress, had more competition: opera star Grace Moore for OneNight of Love and Norma Shearer, playing the frail Elizabeth BarrettBrowning in The Barretts of Wimpole Street, along with a popular write-incandidate, Bette Davis as a slatternly waitress in Of Human Bondage. Colbert,who disliked her own film, was so sure she would lose that when the winner wasannounced she was boarding a train for a cross-country trip. Studio chief HarryCohn immediately dispatched an underling to drag her off her train so she couldappear at the ceremony. Though Colbert was quite cranky about the wholeproduction experience, she’s delightful as the petulant Ellie—and it’s worthnoting that she starred in three other films that same year, including twoadditional Best Picture nominees, the epic Cleopatra and thesocially-conscious Imitation of Life. So maybe she really did need avacation.

Why the film’s popularity? It’s fun, it’sfresh, and it comically addresses the inequitiesof the Depression era, with the common folk coming out on top. What’s not tolove?

October 31, 2024

“Kwaidan”: Just My Cup of Tea for Halloween

My passion for thingsJapanese began early, with my mother’s enthusiasm for the exotic and a highschool friendship that continues to this day. When I was accepted for a year’sstudy in Tokyo, courtesy of the University of California’s Education Abroad Program,an uncle with literary tastes gave me a volume of the writings of LafcadioHearn. Hearn was a total original: born in Greece, raised in Ireland, he cameto the U.S. as a journalist and spent formative years in New Orleans, happilycollecting weird tales and basking in the influence of one of his own favoriteauthors, Edgar Allan Poe. In 1890 he sailed to Japan and never left, taking aJapanese name and a Japanese wife. Collecting ancient Japanese folk tales fullof spectral beings and evil spirits, he carefully rendered them in English andsent them out into the world. In 1964, Japanese filmmaker Masaki Kobayashireturned the favor, assembling four Hearn tales into a film he named after oneof Hearn’s anthologies, Kwaidan (implying ghost stories).

Kobayashi, a specialist in jidaigeki(period drama) featuring samurai and epic battle scenes, was hailed bycritics and audiences worldwide. Kwaidan won him a Special Jury Prize atthe 1965 Cannes Film Festival as well as an Oscar nomination for BestForeign-Language Film. His achievement was to add to Hearn’s bizarre stories agorgeously stylized visual element, a spine-tingling score by Toru Takemitsu,and (particularly in the third tale) a narrative voice that captures theportentous formality of classical Japanese theatre.

My favorite of the storiesmay be the very first, “The Black Hair.” It involves a classic folktalesituation: a man who abandons his sweet, loyal wife to make a more prosperousmarriage elsewhere. While the spurned wife remains behind in their isolatedhome, he ventures into the world and soon weds a wealthy heiress who turns outto be selfish and cold. Once several years have passed, he realizes that,despite his new affluence, he sorely misses his gentle first wife. That’s whenhe returns home, to be joyfully greeted by wife #1, who refuses to rebuke himin any way. They spend a tender night together . . . but there’s a darksurprise awaiting him in the morning.

There are also eerie visualdelights in “The Woman of the Snow,” in which a bone-chilling blizzard plays akey role. The strong Japanese connection with the natural world plays out inall the tales, even though we’re keenly aware of the artifice involved in thefilming process. “Hoichi the Earless” is perhaps the strangest story of all;Kobayashi chooses to precede this tale of a blind monk who’s a musical masteron the biwa by dramatizing the historic sea battle of the Genji andHeike clans in almost Kabuki fashion: I’ll long remember the noble ladies ofthe defeated side ending their lives by plunging into the sea, their heavygarments billowing around them.

The final segment, “In a Cupof Tea,” evolved from a fragment Hearn found embedded in another story. It beginswith an author of the Meiji Period (basically 19th century) writingabout a an attendant to a local lord in some earlier era. When the attendantpours himself some tea, he sees in the liquid the face of an unknown man.Ultimately he drinks the tea—and all hell breaks loose. The story, whichcontains a fierce battle between the attendant and some mysterious assailantsrepresenting the teacup-man, ends abruptly. The author doesn’t know how tofinish it. But Kobayashi does, and thefilm ends with one final, very creepy, frisson.

Beverly in Movieland

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers