Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 10

October 29, 2024

The Dating-Game Killer: “Woman of the Hour”

Sometimes I just don’t getit. I watch a clunky made-for-TV movie on Netflix, then discover that criticshave liked it (it was rated 91% “fresh” on aggregator site Rotten Tomatoes),and audiences do too. Maybe the point is that everyone thinks Anna Kendrick isawfully cute. And I agree. I was won over by her headstrong career gal role in2009’s Up in the Air, for which she nabbed a Supporting Actress Oscarnomination. I liked her roles in other films too, and was impressed by hervocal work as Cinderella in the screen adaptation of Stephen Sondheim’s Into the Woods (2014). More recently shebrought her girl-next-door charm to a mystery-thriller, A Simple Favor

She’s done well for herselfin Hollywood. Which is why I guess she wanted to take the next step andsimultaneously become both a star and a director.

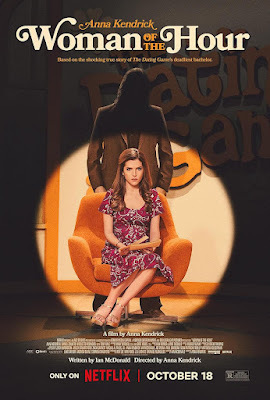

The project she chose was Womanof the Hour, a real-life crime story distributed by Netflix in 2023. Theposter for the movie certainly makes its point: it features Kendrick in apretty 1970s- era floral frock, demurely seated on a big comfy swivel chair.Behind her looms a shadowy male figure. We can’t see his face, but he’s clearlyup to no good. Kendrick stars as Sheryl,a pert graduate of a New York drama school, who’s having a hard time making itin Hollywood. Early on we see her flunk an audition, partly because she refusesto do nudity. Her agent, whose logic doesn’t make much sense to me, persuadesher that an appearance on a popular TV show of the era, The Dating Game, maymove her career forward.

The show’s premise is thatSheryl must choose one of three unseen young men to accompany her on a romanticweekend. Ignoring the suggestions of the smarmy host, she asks questions thatare smart and sassy. Bachelor #1 is basically tongue-tied. Bachelor #2 istrying so hard to be sexy that he comes off as obnoxious. Bachelor #3’sresponses are clever, but also show a sensitivity to female needs.Unfortunately, no one has figured out that he’s Rodney Alcala, a serial killerwho lures his victims with sweet talk, then rapes and murders them. (When ayoung woman in the studio audience recognizes him as the slayer of her bestfriend, no one takes her seriously.)

Because this is a true story,Kendrick and company feel the need to stick to the basic facts. And animportant fact is that Sheryl has absolutely nothing to do with the story’soutcome. In the course of a post-taping drink with her chosen bachelor, shebecomes uneasy, hands him a fake phone number, and leaves the film. When he’slater apprehended it’s because a gutsy teenage runaway he’s raped in the desertfinds a way to escape his clutches and call the cops.

As a longtime teacher ofscreenwriting, I know the importance of understanding your project. IfKendrick’s Sheryl is the leading character, we’d like to see her somehowtrip up the bad guy. If the end of the story belongs to Autumn Best’s pluckyteen, shouldn’t she get more screentime? And what about Daniel Zovatto’s scaryRodney? We know from the start that he’s guilty—shouldn’t we have a bettersense of what makes him tick?

The idea of a serial killeras a contestant on a dating show certainly has potential. Kendrick’s film looksgood, and has its colorful moments. But if we’re supposed to care about amovie’s outcome, it’s urgent that we understand whom we’re dealing with, andwhy.

October 25, 2024

Uncovering “The Shape of Things”

Playwright and film directorNeil LaBute is surely not typical of the graduates at Brigham Young University.I know, and like, a number of BYU grads. (We worked together at Osaka’s Expo70, many moons ago.) The former Mormon missionaries with whom I hung out tendedto be trustworthy, smart, and often a lot of fun. But their political andsocial views were on the conservative side, in keeping with the moral tenets ofthe church that shaped their lives.

LaBute, who studied theatreat BYU circa 1980, is something of a different story. His plays, which he hasalso translated to film, lack the basic optimism that I connect with the Churchof Latter Day Saints. La Bute’s style is to zero in on the worst of humanbehavior and follow where it leads. His first big success, which I saw andadmired years ago, was In the Company of Men, a play that became anindie film and picked up several prestigious critics’ awards, It’s a cold-eyedlook at misogyny in the workplace, with two corporate types joining forces tobedevil a hapless female co-worker, with grim results. (To my surprise, I’vejust learned that this corrosive work debuted at BYU in 1992, andsubsequently won an award from the Association for Mormon Letters. So perhapsnot all Mormons are as optimistic about mankind as my former co-workers.)

The film I saw last night,2003’s The Shape of Things, also started out as a LaBute play. Itdebuted in London with a cast made up of Rachel Weisz, Paul Rudd, Gretchen Mol,and Fred Weller. All four also appear in the film version, which is set on andaround a picturesque American collegecampus, played by the California State University branch in ocean-adjacentCamarillo, CA. Though on-screen other students and faculty members come and go,only the four main actors have speaking roles: there’s no question that this isessentially a filmed play, one in which the focus is narrow and talk isall-important.

At first it’s easy for theviewer to get restless while watching a series of mostly two-person dialoguescenes. But the mating-dance aspect of the script is intriguing, and thecharacters are so wildly assorted that we’re curious to see what comes next. Thestory’s Queen Bee, played by the always fascinating Weisz, is am art studentworking on a mysterious graduate thesis project. Convinced that art trumpseverything (including morality), she is adamant in her choices, one of thembeing to bed a nebbishy young man who works—after a fashion—as a guard at thecampus art museum. As played by an initially unrecognizable Paul Rudd, he’s alltoo willing to be molded by this beautiful and outrageous young woman, whohelps him find the self-confidence he has lacked. The main cast is completed byFred Weller, as Rudd’s domineering best friend, and his apparently meekfiancée, the perky blonde Gretchen Moll. There’s a powerful twist ending that Iwouldn’t dream of divulging, but suffice it to say that there’s not a lot ofhappily ever after.

LaBute, who shares with DavidMamet a facility for language as well as a basic pessimism about human nature,makes vivid the cruelty of the characters toward one another. This particularpiece of work also has fun satirizing the art world. LaBute takes on both theprudes of the past (a giant plaster fig-leaf covering the genitalia of an artmuseum statue is key to the story’s beginning) and the hip art-for-art’s-sakeconvictions of the present. If you like witty misanthropy, this one’s for you.

October 22, 2024

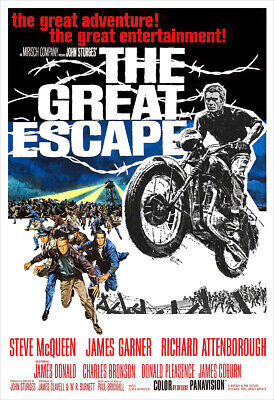

“The Great Escape” -- Not Exactly Escapist

It used to be that all I knewabout The Great Escape was Steve McQueen on a motorcycle. I figured this1963 film was basically a precursor to 1968’s Bullitt (except that it’sset in a war zone instead of in the hills of San Francisco). In other words, Iassumed it was intended to be an exercise in rugged machismo, definitelytailored to the males of the species. And so, in a way, it is. I don’t believethere’s a single female in the movie who has so much as a line of dialogue.It’s a men-without-women story all the way.

But The Great Escape isa great deal more complex, more historically-based, and more emotionallycharged than Bullitt. Most of the nearly-three-hour running time isspent in a World War II prison camp designed by the Nazis to make escapeimpossible. It’s not, as prison camps go, a terrible place to be. But a largecontingent of military prisoners (mostly British and American) are quitewilling to risk their lives to plan and carry out a mass escape through cleverly crafted underground tunnels they’vemanaged to dig by hand. Part of what makes the film important is that theescape really happened, though in fact many nationalities were involved, andAmericans had only a small role in the break-out plans. As in real life, themoments of triumph in the film go hand in hand with tragedy. Yes, there’s agreat escape, but—as in the actual historical episode—the upshot is not a goodoutcome for many who are deeply involved.

Part of what makes the filmfascinating is the way it shows how individuals of various stripes can cometogether to pursue a common goal. The prisoners hail from a variety ofbackgrounds, and can boast a variety of useful skills. The McQueencharacter—the ruggedest individual of the bunch—was in civilian life a studentof structural engineering. At first determined to go on the lam solely on hisown, he becomes an important cog in the bigger plan. Others have vastlydifferent skills. Richard Attenborough plays a natural leader with foreignlanguage abilities; James Garner is an expert scrounger; James Coburn isfeatured as an Aussie who is terrific at inventing useful contraptions. Someexperienced tailors in the group craft civilian clothing for the guys to wearon the outside; some prisoners with forgery skills turn out counterfeit traveldocuments that look like the real thing. Of course there are individual crisesas the escape plans are finalized. Charles Bronson, using an Eastern Europeanaccent like the one he grew up with, plays a former miner, an experttunnel-digger who happens to be severely claustrophobic. Another of the would-beescapees can’t deny that he is going blind. The film follows many of these menas they taste freedom for the first time in many months. What’s particularlymoving is that several of the men put themselves in mortal danger byvolunteering to buddy up with more vulnerable prisoners who’ll never survive ontheir own.

Making all of this activitycoherent is one of Hollywood’s greatest action directors, John Sturges.Starting as an editor, Sturges moved into the director’s chair, always showinga special talent for portraying groups of men in action settings. Prior to TheGreat Escape, he helmed Bad Day at Black Rock (1955), Gunfight atthe OK Corral (1957), and The Magnificent Seven (1960). Lots of hisfilms feature tough guys and the serious jeopardy they face, but he liked toend with a modest but genuine sense of triumph.

October 18, 2024

Mary and the Bear

It was the long, dark days ofthe pandemic that introduced me to the pleasures of watching television.Desperate for entertainment, I turned to cable-tv for long-running recentseries I’d missed, like Mad Men and Breaking Bad, but also forsitcoms that took me back to my early years.

After giving some love to ILove Lucy, I settled on the pleasures of The Mary Tyler Moore show,which ruled the airwaves from 1970 until 1977. The show may look dated today,with its multi-camera style and laugh-happy studio audience. But back in the1970s it was known for tackling social issues that were very much in the air.Its star, as Mary Richards, was an unmarried career gal who had the occasionalromance but was much more involved with her job as the producer of a localMinneapolis TV news show. In the early seasons, she had colorful interactionswith her landlady (Cloris Leachman) and her best buddy (Valerie Harper). Butmost episodes featured her interactions with the newsroom gang, thecurmudgeonly Lou Grant (Edward Asner),the acerbic Murray Slaughter (Gavin McLeod), and the irresistibly pompousnewscaster Ted Baxter (Ted Knight). The cherry on top in later years was thefrequent presence of Betty White as a man-hungry TV personality known as theHappy Homemaker.

Though the series was playedfor laughs, at times it ventured boldlyonto serious topics, like infidelity, divorce, erectile dysfunction, and evendeath. (The “Chuckles Bites the Dust” episode is a comedy classic, in whichMary struggles to avoid laughing at a death that occurs under bizarrecircumstances..)

Network television seasonswere long back then: 24 episodes of this show aired per year. There wasoccasional follow-through: in season 4, Lou’s wife walks out on him to findherself. Several seasons later, she’s remarrying, and Lou and Mary reluctantly attendthe nuptials. But basically the episodes are self-contained: the contents ofone show generally do not carry over to the next. This ends up beingparticularly weird at the end of the next-to-last season, when Ted and new wifeGeorgette, despairing of having a baby, adopt a polite seven-year-old boy whocharms everyone in the news room. The kicker is that Georgette then discoversthat, against all odds, she’s pregnant. When the show resumes the followingseason, Georgette is in the throes of giving birth during a party at Mary’sapartment. But that cute little adoptee is never mentioned. Did he run away?Did they return him to the agency?

All this comes to mindbecause we’ve just finished watching the first season of Hulu’s The Bear. LikeThe Mary Tyler Moore Show it’s an Emmy winner in the field of comedy,though it lacks anything you might call a joke. Inside of being performed infront of a live audience, this story about the running of a Chicagoneighborhood restaurant is shot in cinéma vérité style, with theoverlapping dialogue coming thick and fast, and home audience struggling tounderstand everything that’s said. (The show also consistently relies onexpletives that Mary Richards has doubtless never used, or even heard.)

If The Mary Tyler MooreShow occasionally edges into darker territory, The Bear lives therefulltime. Its characters cope with the aftermath of addiction and a brother’ssuicide, and shady hangers-on are always lurking around. Funny? I’m not sosure. (Neither are the Emmy voters who chose a different winner in thiscategory for The Bear’s second season.) But the ongoing story—whichdoesn’t fully come together until the last episode of season 1--is fascinating,and well worth watching.

October 15, 2024

Katharine Hepburn is (and is not) Sylvia Scarlett

I just finished watching anearly cinematic romp starring Katharine Hepburn and Cary Grant. Bringing UpBaby? Nope. The Philadelphia Story? Still nope. While reading an advance copy of JosephMcBride’s fascinating George Cukor’s People: Acting for a MasterDirector, I became curious about a vintage film I had only barely heard of.Its name: Sylvia Scarlett. This 1935 flop was Cukor and Hepburn’squixotic attempt to circumvent the Hollywood standards of the day. It’s thestory of a young woman trying to protect her petty-criminal father bydisguising herself as a young male as the two go on the lam, Hepburn’stransformation from female to male and back again was not taken well by theaudiences of the day, nor by Hepburn’s studio, RKO, which demanded an ineptexplanatory prologue in which she appears in long braids and speaks in a meekgirlish voice.

The questions about genderand sexuality just beneath the film’s surface have belatedly made SylviaScarlett a favorite of feminists and some branches of the gay community.Personally, I consider it something of a mess, though a fascinating one.Various aspects of the plot are inconsistent, or just don’t make sense.Hepburn, though, is a marvel to watch. After that silly prologue, Hepburn in croppedhair and boys’ clothing is wonderfully convincing. The film makes full use ofher natural athleticism (we see her jump over fences and climb through windows,and there’s a key instance when she plunges into a turbulent ocean to savesomeone from drowning). There are also those magical moments when she seemstrapped by her disguise, trembling on the brink of declaring that she/he is inlove. But when she decides to give in to her undeniable female self, dressingin a filmy frock and picture hat, we don’t believe her at all. Though Hepburnas pretty ingenue seems to enthrall the eligible men around her, it strikes theaudience as a grotesque betrayal of her genuine personality.

It was especially this filmthat caused Hollywood to label Hepburn “box office poison.” When she regainedpopularity, it was through roles that allowed her to be spirited and spunky,but also much more conventionally female, and ultimately content to accept abit of male domination. See, of course,her later outings with the hyper-male Spencer Tracy, and also her role oppositeCary Grant in Cukor’s The Philadelphia Story, wherein machismoultimately wins the day. But the Sylvia Scarlett project hints that Hepburn,like the not-so-closeted Cukor, was shaped by a form of sexuality that was outof the ordinary, what we might call a complex mixture of yin and yang.

The DVD version I watched,part of the Warner Brothers archive collection, has as an extra a short vintagetravelogue that should delight every Angeleno. Advertised as A FitzPatrickTravel Talk, this Technicolor short is titled “Los Angeles, Wonder City of theWest.” The L.A. about which the narrator enthuses (consistently calling myhometown “Las Angle-Us”) was then the country’s fifth largest city, boasting apopulation of 2 ¼ million souls. The travelogue begins with the lovely“Spanish” senoritas of Olvera Street, then coasts down “modern” thoroughfares,waxing lyrical about wacky features like the long-gone Brown Derby. Of coursethere’s a visit to several movie studios, complete with a sighting of WaltDisney himself, bouncing out of his modest headquarters to smile amiably forthe camera, as “Whistle While You Work” plays on the soundtrack. We end up atthe Hollywood Bowl, as some cuties and muscle-men rehearse a “cultural” danceperformance that looks like pure kitsch. Those were the days!

October 11, 2024

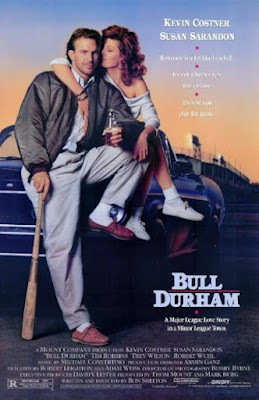

Baseball in Durham is No Bull

Last Wednesday, while my L.A.Dodgers were thrashing the San Diego Padres, trying to inch toward a majorleague title (fingers crossed!), Idecided to rewatch my all-time favorite baseball movie, 1988’s Bull Durham. Tomy surprise, it was released the year before Kevin Costner starred as adreamy Iowa farmer who wills a vintage baseball team into being as a way ofreconciling with his dead father in Field of Dreams. The Costner of Fieldof Dreams was young, fresh-faced, idealistic, and basically innocent. In BullDurham, though, he seems perhaps a decade older, much smarter and morecynical, someone who has tried and failed to fulfill his early promise.

Part of Bull Durham’ssuccess comes from the fact that it was written and directed by someone whoreally knows the sport, knows what happens on the field—and off. Ron Shelton, aformer minor league infielder, brings to the film a gritty understanding of howbaseball is played, and what games are played in the shadow of America’sNational Pastime. This was his first film as a director, and it has led him toscore with other sports-related projects, like White Men Can’t Jump (1992,about the world of playground basketball hustlers), and Tin Cup (1996,about professional golf, once againstarring Costner). Wikipedia notes that “in 2022, Shelton's book TheChurch of Baseball: The Making of Bull Durham: Home Runs, Bad Calls, CrazyFights, Big Swings, and a Hit was published by Vintage Books. Itsounds worth reading.

Although Bull Durham dealswith the exploits of a minor-league baseball club, the Durham (North Carolina) Bulls,it is less about a team and more about three individuals who are very much inthe team’s orbit. The film’s opening line belongs to Susan Sarandon, who asAnnie Savoy starts us out, in voiceover, with her philosophy of life. It beginswith “I believe in the church of baseball,” then goes on to philosophize aboutthe game as a sort of earthy substitute for formal religion. The provocativeAnnie, who during the year teaches literature, dedicates her summers toeducation of a different sort. Settling on a young, attractive player, sheenjoys hot sex while also building his confidence and throwing in some lessonsin basic baseball skills. For this particular summer, she chooses the naïve butmega-talented Ebby Calvin Latoosh (Tim Robbins), a pitcher who is as of yet tooerratic and too cocky for stardom.

The third member of this verydynamic triangle is “Crash” Davis (Costner), a worldly-wise catcher who oncespent 21 days in the major leagues, doing nothing very spectacular before beingsent back down to the minors. With his playing days numbered, he’s been addedto the Durham roster to keep Latoosh under control and try to clue him in tothe secrets of big league success. Smart but prickly (even though he’s aromantic at heart), Crash captures Annie’s interest when he strongly rejectsthe idea of auditioning for a role in her menage. Naturally, the sense thathe’s his own man, and not one of the adoring “boys” who surround her, piquesher curiosity.

In a sense this is a filmabout the clash of innocence and experience, as well as about the push-and-pullbetween talent and wisdom. At the film’s end, Latoosh is headed for the majors(having learned a few life lessons along the way) but who’s to say that Crashwon’t be happier in the long run? The irony is that in real life Sarandon andthe much younger Robbins ended up together for more than two decades.

October 8, 2024

Maggie Smith and Kris Kristofferson: The Lady and the Tramp

Alas, in the past week or so,we’ve lost several of my screen favorites. Dame Maggie Smith (who diedSeptember 27 at age 89) can fairly be considered movie royalty. I can’t pretendto have seen all her stage and screen work, but –starting in the late 1950s—sheexcelled at both comedy and drama, in both new works and well-aged classics.Circa 1970, I was lucky to catch her touring in an arch 18th centurycomedy, The Beaux’ Stratagem, opposite her then-husband, RobertStephens, when it touched down at L.A.’s Ahmanson Theatre. But my firstencounter with her talents came earlier, when she played an intelligent andsensitive Desdemona in a film version of Shakespeare’s Othello, withnone other than Sir Laurence Olivier in the title role. (His blackfaceperformance of the tragic moor was a dramatic tour de force, thoughtoday we’d naturally be uneasy seeing a white actor pretend to be a person ofcolor.)

Her Desdemona earned MaggieSmith her first Oscar nomination. In all she was nominated six times, winningthe golden statuette for her fierce dramatic role in The Prime of Miss JeanBrodie (1969) and for her supporting part in a Neil Simon comedy, CaliforniaSuite (1978). Her two final supporting actress noms were for “corset” rolesin A Room with a View (1985, as a prim chaperone) and Gosford Park (2001,as an ageing aristocrat). A whole new generation fell in love with her as thetart-tongued Violet Crawley in a period drama made for television, DowntonAbbey (2010-2015). Playing an aristocrat raised in an earlier age, she wastotally oblivious of more modern conventions, like weekends, and we adored herfor that. But kids also fell under her spell when she played to perfection thesensible (though magical) Professor Minerva McGonagall in the Harry Potterfilms.

Maggie Smith did not alwaysplay aristocrats and intellectuals. She was capable, as well, of portrayingwomen of the lower classes. In 2011’s charming The Best Exotic MarigoldHotel and its sequel, she is a retired housekeeper worried about finances,one who only slowly adapts to the charms of India. As the title character inAlan Bennett’s semi-autobiographical The Lady in the Van, she’s aneccentric who makes her home for 15 years in Bennett’s driveway, dominating hisdaily life in ways both aggravating and fascinating. But whatever the roots ofthe characters Smith played, she always displayed a certain dignity, what youmight call a ladylike manner. Yes, there was something proper and British abouther, no matter the role.

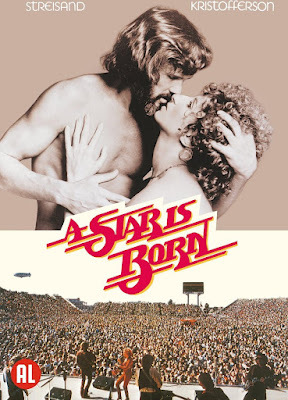

By contrast, KrisKristofferson (who passed away on September 28 at age 88) was as American asApril in Arizona. This despite the fact that his upbringing was highly out ofthe ordinary. An army brat, he was born in Texas, was an honor student (as wellas a rugby star) at California’s Pomona College, and traveled to England as aRhodes Scholar to study literature at Oxford. Following a stint as a military officer, he angered his family bychoosing to move to Nashville, in searchof success as a writer of country music. Eventually such songs as “Me and BobbyMcGee” made him successful, and his rugged good looks helped him move intoacting, in major films that cast him as outcasts, drifters, and close-to-the-earthtypes. (See, for instance, Martin Scorsese’s 1974 Alice Doesn’t Live HereAnymore and John Sayles’ 1996 Texas border saga, Lone Star). Hisschmaltziest role was as Barbra Streisand’s rock-‘n’-roller husband in the 1976iteration of A Star is Born.

Both will be sorely missed.

October 3, 2024

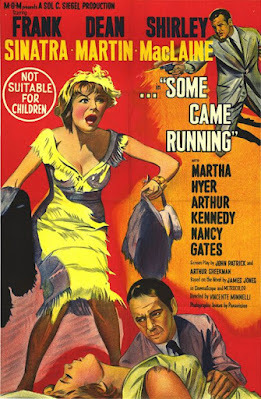

Some Came Running, Some Stayed Away

In 1951, World War II veteranJames Jones published a blockbuster novel about the lives and loves of Americantroops stationed in Honolulu at the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor. When FromHere to Eternity became a film two years later, it took Hollywood by storm.Its 13 Oscar nominations resulted in eight wins, including Best Picture, BestDirector, and a statuette for Frank Sinatra, bringing his own bitterness andpugnacious spirit to the role of Maggio, as the year’s Best Supporting Actor.

It seemed the combination ofJames Jones’ writing and Sinatra’s acting chops was a potent one. That’s why,when in 1957 Jones published a second novel—this time dealing with a returningsoldier during the post-war period—Hollywood again came calling, ready to starSinatra as a tough-but-tender protagonist in another James Jones adaptation. But Jones’ new novel, Some Came Running,had a few problems. The New Yorker’s critic colorfully called it “twelvehundred and sixty-six pages of flawlessly sustained tedium.”

This was the shoot on whichSinatra, always an impatient actor, apparently ripped twenty pages out of thescript in order to keep the film’s length close to the two-hour mark. DirectorVincente Minnelli, looking for a change of pace from his own sparkling Gigi(also from 1958), had the challenge of corralling Sinatra and co-star DeanMartin, while also staying true to his own artistic vision. It culminated in abrilliantly florid climax, set at night amid the gaudy neon lights of asmall-town carnival. The film earned five Oscar noms, mostly in actingcategories, but not a single win. (Gigi and the actors from SeparateTables were the year’s big awards recipients.)

I’ve heard film scholarspraise the aesthetics of Some Came Running, as well as Minnelli’s blunttreatment of the hypocrisies of Midwest life. And I can’t deny that there aresome strong performances, notably that of Shirley MacLaine (nominated for herfirst Oscar for this, her all-time favorite role). She plays Ginny, a slightlytawdry but good-hearted waif whose love for Dave leads at last to tragedy. (Thefilm’s tweak of the novel’s original ending definitely increases itspoignance.) There’s also good work by Sinatra and by his pal, Dean Martin, as ahard-drinking gambler who’s lovable but on a path to self-destruction.

All this should make it clearthat the film’s plot is an intensely melodramatic one, with far too manycharacters and lots of lurid small-town misbehavior. When Sinatra’s character,in military uniform, gets off the bus in his old hometown, it’s clear he’s abit disgusted by the locals, but even more unimpressed with himself. Thoughhe’s published several novels and has something of a literary reputation (like,of course, James Jones), he seems unable to move forward with his writingcareer. He’s also got a serious grudge against the well-heeled brother (ArthurKennedy) who’s now one of the town’s leading citizens but chafes at his wife’ssnootiness, to the point where he strays with an attractive employee.

Oddly, it’s through hisbrother that Sinatra’s Dave comes to know a local professor and hisschoolmarm-daughter, both of whom highly respect him as a man of letters. We’resupposed to believe that the prim schoolteacher (Martha Hyer) is Dave’s truelove, though—aside from a rare moment when he literally takes her hair down—sheseems incapable of passion of any sort. Her scenes with Sinatra come across as stodgy, as she lectures him onliterature and life. Under the circumstances, a gauche, umgrammatical Ginnywould seem like an improvement, especially given MacLaine’s wistful charm.

October 1, 2024

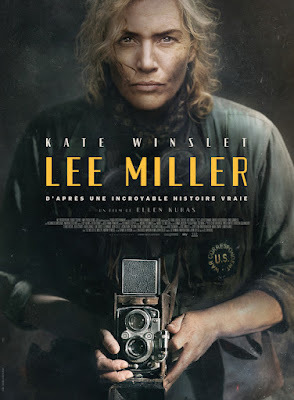

A Close-Up of War Photographer Lee Miller

Regarding the new film, Lee,Kate Winslet can’t be accused of attaching herself to a vanity project designedto make her look good. True, she servedthis biopic of World War II photojournalist Lee Miller as producer as well asstar, reportedly laboring for five years to help it come to fruition. Now thissober but fascinating new work, a first directorial outing by veterancinematographer Ellen Kuras, is in theatres, giving all of us a chance to focuson Winslet’s dedication to her subject. Her Lee is attractive enough to be a formermodel (as well as the muse and lover of avant-garde artist Man Ray, amongothers), and she lives her life as a expat in Europe with a kind of wildgaiety. (At a co-ed picnic on the grass in the south of France, she’s casuallytopless). But following the rise of Hitler, she leaves her partner behind inLondon to work as a photojournalist, first in occupied Paris and then behindthe front lines in Germany as the War in Europe grinds to a close. This is awoman who can’t take no for an answer, who’s determined, at all costs, toexercise her talents and exorcize her demons.

Lee may speak fluent French,but she’s American-born, and she talkswith a kind of raspy croak that perhaps hints at her future death from lungcancer. (She lights up so frequently during the film that I perversely fearedmoviegoers might have their lungs damaged by second-hand smoke wafting from thescreen.) Never one to fuss with her appearance, she stalks through militarycamps and the streets of war-torn cities looking disheveled and ready to takeon anyone who gets in her way. Curiously, she’s on assignment for the Britishedition of Vogue, a magazine much more associated with fashion trendsthan with war coverage. Yes, partly because the top military brass try hard tokeep her away from the blood and guts of battle, she turns in her share of warphotos from a woman’s perspective, like snaps of the intimate laundry of femalepersonnel hanging from a military tent’s makeshift clothesline. But she alsosees—and documents—what women go through in wartime, always showing sympathy tothose (even on the enemy side) who have made the mistake of trusting male lies.

The film’s climax is Lee’svisit to the newly discovered concentration camps and railroad boxcars in whichmillions of Jews, dissidents, and others breathed their last. These horrificplaces answer for her the question of what happened to her missing Frenchfriends as well as others who were not considered acceptable by the Naziregime. Her close-up photos of piles of rotting corpses, although at firstrejected by Vogue as overly disturbing to its potential readers, are todayconsidered invaluable documentation of what the Nazis did to hapless civilians.In the face of those atrocities, it’s hard to blame her for a slightly morbidjest: inside Hitler’s cushy former home, she cheerily photographs herself inthe buff, soaking in his private bathtub.

But all was not fun and gameswithin Lee’s personal and professional life. We’re reminded of this in thecutaways to an aged and much-diminished Lee (still feisty, still smoking) beinginterviewed in her farmhouse by a dapper young reporter. The last of theseinterview scenes reveals several things about Lee we had not expected,contributing to our sense of her as complicated indeed. It’s worth noting thatfamily members—determined to preserve Lee’s legacy—were deeply involved themaking of this film, about a woman we should all know better.

September 27, 2024

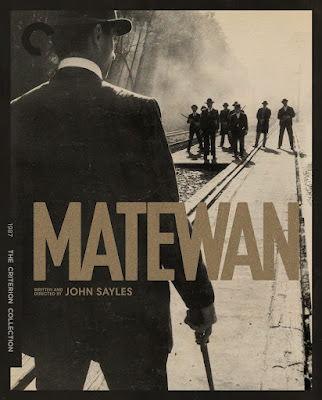

Digging Deep into John Sayles’ "Matewan"

If it weren’t for RogerCorman, John Sayles may never have come to Hollywood. Back in the lateseventies, Roger was looking for a bright new—and inexpensive—screenwriter forone of his low-budget genre flicks. He assigned his longtime story editor, mygood friend Frances Doel, to comb through the best literary magazines, lookingfor a promising young master of prose fiction who could be converted into ascreenwriter. In Esquire she discovered Sayles, a youthful novelist andshort story writer who was eager to go west. His first screen credit was forthe scripting of Piranha, a darkly comic take on the über-popular Jawsthat featured, instead of one deadly giant fish, a whole lot ofdeadly tiny fish. He followed this with a screenplay for Julie Corman’s TheLady in Red, all the while immersing himself in the skills he’d need tosucceed as a film director.

It was not long before Sayles applied his Cormanearnings to his own first film as a writer-director, 1980’s Return of theSecaucus 7. (White writing my biography, Roger Corman: Blood-SuckingVampires, Flesh-Eating Cockroaches, and Driller Killers, I was thrilled tospeak at length to Sayles about how the lessons he’d learned from Cormancontributed to his long career as a maker of truly independent films.)

In the 1980’s, while writingincreasingly impressive scripts for others, Sayles continued to pursue his ownidiosyncratic career, exploring a wide range of genres. One of his greatestachievements has been 1987’s Matewan, a powerful drama about thereal-life struggle of West Virginia coal miners to form a union, in the face ofarmed resistance from their bosses.

Walking a fine line between the realistic and the mythic, Sayles captures thedownhome heroism of the striking miners as well as the stark beauty of theirsurroundings. (Legendary cinematographer Haskell Wexler, who surely appreciatedthe script’s clear proletarian slant, was rewarded by the Academy with an Oscarnomination for this film.)

Though Sayles’ feelings forthe union cause are self-evident, the central conflict in the film is hardly justblack-and-white. The striking West Virginia mine-workers (some younger thanfifteen) tend to start with a bigoted attitude not only toward theAfrican-American scabs who descend on the town of Matewan but also toward therecent Italian immigrants trying to make their home in this locale. And they’reall too willing to use violence to express their feelings. (Everyone, includingthe local housewives and a teenaged lay preacher, seems extremely familiar withfirearms.) This is a place, it’s made clear, that was founded on God and guns.Sayles himself has fun with the small role of the local minister: he’s appearedin many of his own movies, as well as in the films of oth

Over the years, Sayles hasdeveloped a small stock company of actors who return to his projects time andagain. Several of them, including Gordon Clapp and David Strathairn, have beenwith him since campus days at Williams College. Matewan also has a keyrole for Mary McDonnell: this was only her second film, three years before shefound fame and an Oscar nomination for her supporting part in Dances WithWolves. (In 1992, Sayles put her at the center of his Passion Fish,which brought her a Best Actress Oscar nom.) Late great James Earl Jones also playsa essential part in the Matewan action. But the most heroic character isthe union organizer, a deeply committed pacifist, played by Chris Cooper, atthe very start of his movie career.

Beverly in Movieland

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers