Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 12

August 20, 2024

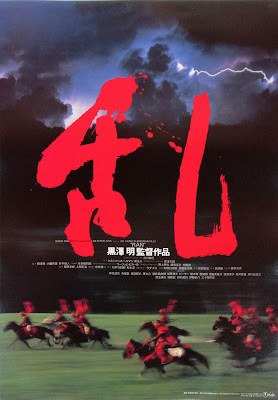

“Ran”: The Dangerous Women of Akira Kurosawa

Akira Kurosawa started makingfilms in Japan during World War II. I’ve seen one of his most charming earlyefforts, The Men Who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail, a period piece based onancient Kabuki and Noh plays about some roguish samurai who disguise themselvesas monks. Made in 1945 (but not released until 1952), it features Kurosawa’ssignature blending of high and low-class characters.

Another jidaigeki (or“period drama”), one that brought Kurosawa international fame, was Rashomon,a 1950 adaptation of stories by Ryunosuke Akutagawa. Starring such Kurosawaregulars as Toshiro Mifune, Machiko Kyo, and Takashi Shimura, it deals with themysterious death of a samurai in a woodland setting. Three versions of whathappened are brought forward: one taleis told by the samurai’s wife, a second by the bandit who accosted the pair, athird by the dead samurai from beyond the grave, speaking through a medium. Ineach version, the teller comes off very well indeed. Finally, a woodcutter whohas spied on the entire incident gives his own account, in which the threeprincipals are all self-serving and comically inept.

One of the delightful elements of Rashomonis its handling of the lady who is the samurai’s wife. In her own telling ofthe story, she is both modest and noble, heroically defending her virtueagainst the marauding bandit. But other versions reveal her to be quitedifferent: lascivious and something of a shrew. Traditional Japanese culture sooften portrays females as paragons of virtue, or as long-suffering MadameButterflies. But Kurosawa, to his credit, acknowledges that women are not soeasily categorized.

Certainly, this is the casein Kurosawa’s 1957 Throne of Blood, his feudal Japanese retelling ofShakespeare’s Macbeth. The dangerously ambitious Lady Macbeth, herecalled Lady Asaji Washizu, is truly a horror. Of course this portrayal follows the leadof the sixteenth-century English playwright who first invented her. But in hislate-in-life 1985 masterwork, Ran, Kurosawa adds to the familiar storyof King Lear an additional element that shows a woman in a very harsh,though highly dramatic, light.

King Lear, needless to say, begins with an ageing monarchretreating from public life by offering his kingdom to his three daughters. Hewrongly assumes they will continue to honor him in his old age, only to findthat the two he has favored have no use for him now that he lacks power. Ran,tells a similar story about a fictional warlord named Hidetora Ichimonji,who chooses to leave his kingdom to his three sons. As in King Lear, the two eldest turn on him;only the third son—the honest one he has rejected—comes through in his momentof need. Because this is a jidaigeki, there is much brutal jostling forpower, featuring what looks to be a cast of thousands. But there is also asubplot that is nowhere to be found in Shakespeare.

Lady Kaede, the wife of theoldest son, has much reason to hate her father-in-law, who once destroyed herentire family in order to claim their castle for himself. When first seen,she’s protesting that she feels no anger; as a Buddhist she understands that noneof us can avoid the whims of fate. But after her husband’s death in battle, thegrieving widow shows up in his brother’s quarters: and suddenly her meeknessexplodes into wrath. Brandishing a very sharp knife, she first threatens toslice his throat . . . and then the scene becomes an erotic tryst. This is herform of revenge, and it leads to retribution that is hardly pretty.

August 16, 2024

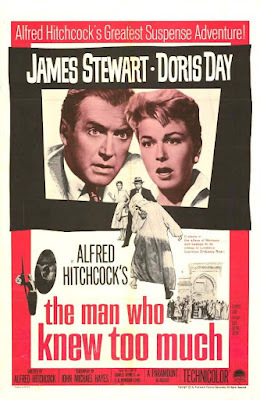

Hitchcock-Lite: “The Man Who Knew too Much”

I’ve never seen Alfred Hitchcock’s 1934 British version of TheMan Who Knew Too Much. It’s a thriller, of course, one that climaxes withan assassination attempt planned for a climactic orchestral moment at London’s Albert Hall. Peter Lorreis involved as a criminal mastermind, so you know that things are going to get seriouslycreepy.

More than twenty years later,Hitchcock basically recycled his original plot for Hollywood. His 1956 take on TheMan Who Knew Too Much is 45 minutes longer than the British version, andfeatures two of Hollywood’s most popular actors, James Stewart and Doris Day.(Taking advantage of Day’s musical chops, Hitchcock and company make her aretired singing star, and weave into the plot her crooning of a new song, “QueSera Sera,” which ultimately won an Oscar.)

As in so many Hitchcockfilms, the leading characters are innocents who find themselves caught up in anevil scheme they must ultimately help to foil. See, for instance, the classic Northby Northwest, in which businessman Cary Grant ultimately helps uncover someserious skullduggery.. In The Man Who Knew Too Much, Stewart andDay play a married couple traveling abroad with their young son. In Moroccothey meet a mysterious Frenchman whose sudden death embroils them in intrigue,resulting in young Hank being kidnapped and whisked off to England. Of coursethe rest of the film involves the couple’s desperate search for their child,certainly a matter of the greatest seriousness. But this is a movie in whichHitchcock’s playful side shines through. Though the kidnapping of a kid ishorrendous, we in the audience are never in doubt about Hank’s ultimate safety.That’s because Hitchcock plays down the jeopardy he faces, while devoting muchof the film to the comedy of innocents abroad trying hard to grapple with unfamiliarcultures and unexpected bad guys.

We first meet Ben, Jo, andyoung Hank McKenna on a bus ride from Casablanca to Marrakesh, where theyimmediately run afoul of local customs. (As the bus lurches, Hank accidentallysnatches the veil off a Muslim woman’s face.) Though they’re surrounded byquestionable characters, the focus is on the comic joshing and bickering ofhusband and wife. He’s an Indiana doctor, and at one point they humorously note how his various operationsback home have helped fund the luxuries they’re enjoying on this trip. Andthere’s a great deal of comedy in the key scene where they make new friends atan authentic Moroccan restaurant. (The tall, lanky Ben can’t manage the lowcouches in the dining room, nor can he figure out how to successfully eat withone hand, Moroccan-style.)

Even after the horror theyface when they learn of their son’s abduction, the McKennas are thrust intosituations that can only be called comedic. When they arrive in London, agaggle of British friends descend on their hotel suite, eager to reminisceabout old times. While Ben dashes off to confront a certain Ambrose Chappell,who may hold the key to their son’s whereabouts, Jo is ordering drinks anddesperately trying to entertain these unwanted guests. Ultimately, the actionmoves to the Albert Hall for that climactic concert. (Composer BernardHerrmann, who wrote the score containing the would-be-fatal cymbal crash, makesa cameo appearance as the orchestra’s conductor). When all three McKennas,reunited at last, return to the hotel, they find their guests are stillensconced in their suite, totally snockered.

The famous Hitchcock cameo?It’s not one of his better ones--and thesame goes for this enjoyable but very slight film.

August 13, 2024

The Olympic Games Go Hollywood

Now that the Paris Olympicsare history, I can go back to watching movies instead of international sportingevents. But I must say I fully enjoyed 16 days of stirring competition, despitethe sometimes smarmy NBC coverage and (of course) the endless commercials. Thegames themselves were mostly a delight: exciting outcomes, lots of sidelinedrama, and the most beautiful locations imaginable. (How can L.A. in 2028possibly hope to compete with those shots of the Eiffel Tower? Honestly, theplugs at the end of the late-night broadcast for our next Olympic Games made mybirth city look gorgeous, though I’ve learned that a lot of the hoopla on thebeach was filmed not in L.A. or Santa Monica but some miles down the freeway inLong Beach.)

Once upon a time, I was luckyto attend the closing ceremonies of the 1984 Los Angeles Olympic Games. It wasa simpler era, with less demand for outsized spectacle. The highlights, as Iremember them, included the finale of the first-ever women’s Olympic marathon:we all cheered for the last-place finisher as she staggered painfully into theColiseum, clearly ailing but waving off medical help because she was determinedto finish the race. There was also Lionel Ritchie singing about partying asthough it were 1999 (that date seemed so far off!). And the Joffrey Ballet(then L.A.-based) performed in tandem with a Korean dance troupe, as a preludeto 1988 in Seoul.

One thing that surprised meabout Paris 2024 was the TV coverage’s repeated emphasis on Hollywood stars inthe stands. The NBC cameras picked out the celebs: Nicole Kidman, NataliePortman, Matthew Broderick and Sarah Jessica Parker, et al. Then of coursethere was the constant intrusion of ageing rapper Snoop Dog, sometimes with hisBFF (really!) Martha Stewart. True, Snoop does come off as surprisingly endearing,but I would have strongly preferred coverage of some of the more obscure sportsand some of the more exotic national teams. I’m sure they had their own storiesto tell.

At the Paris closingceremony, following a rather overblown dance-drama about the resurrection ofthe Olympic games of ancient Greece, we moved into an L.A. state of mind via amemorable stunt that underscored the Hollywood aspects of Southern California. It featured none other than Tom Cruise,plunging into the stadium from on high, grabbing the Olympic flag, and roaringoff on a handy motorcycle, heading through the streets of Paris to anL.A.-bound plane. What fun! But also a promise that LA 2028 would be heavilyinvested in Hollywood star culture.

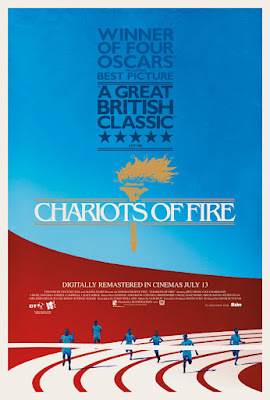

Which made me muse about how many movies have used the Olympicsas their climax. Some have been silly (like Walk, Don’t Run, a wildlyexaggerated look at Tokyo 1964 that featured race-walking and Cary Grant). Somehave been stirring, like The Boys in the Boat and (best of the lot) Chariotsof Fire. Of course there have been documentaries too. The most notorious isOlympia, the portrait of the 1936 Munich games by Adolf Hitler’sfavorite filmmaker, Leni Riefenstahl. Tasked with glorifying the Fatherland, sheintroduced brilliant camera techniques that are still widely used today. Shealso included plenty of awe-inspiring Hitler footage, but couldn’t resistaccording the same admiring gaze to the Black American athlete Jesse Owens, whowon four gold medals in track and field events.

It used to be that newly-mintedOlympic champions went to Hollywood and got turned into movie stars. LikeJohnny (Tarzan) Weissmuller and skating cutie Sonja Henie. But it didn’talways work. Remember the acting career of Mark Spitz?

August 9, 2024

Barbershop Blues: “Bernice Bobs Her Hair”

Who knew that a haircut couldcause such a commotion? In 1920, the young F. Scott Fitzgerald published in theSaturday Evening Post a short story he drew from his younger sister’ssocial anxieties. It was called “Bernice Bobs Her Hair,” and the title hadalways made me curious. I finally caught up with Bernice and her social set viaa 1976 episode of The American ShortStory, an ambitious TV anthology series hosted by PBS between 1974 and1980. The 17 episodes all featured major Hollywood stars and first-classdirectors presenting works by some of America’s most revered authors, includingMark Twain, Hemingway, and Flannery O’Connor.

At the close of PBS’s46-minute Bernice Bobs Her Hair, one of the major production creditsgoes to a wig-maker. This is hardly surprising, because all the women in thestory start out with great masses of long hair, which (true to the style rulesof 1920) they pile onto their heads during the day and arrange into long, thickbraids before going to sleep. One of these proper young ladies is Bernice(Shelley Duvall), visiting her big-city cousin Marjorie from her home in EauClaire, Wisconsin. Marjorie is a social butterfly, who knows how to flirt withthe young men, back for the summer from Ivy League colleges, who are at herbeck and call. Bernice, by contrast, is shy and awkward; her only social gambitis to complain about how much hotter St. Paul is than Eau Claire.

Finally, pushed by her motherto treat her cousin more kindly, Marjorie tutors Bernice on how to flirt, andhow to become a witty conversationalist, going right up to the edge of socialpropriety. Learning her lessons perhaps too well, Bernice begins to enthrallthe young men with daring remarks. At a swanky dinner party, she announces herdetermination to bob her hair, in emulation of the sexy “picture-show vampires”of the day. (Today we would call them “femmes fatales“ or “vamps.”) Herlisteners, accustomed to far more conservative styles, are both fascinated and scandalizedby her daring. She acknowledges that for a woman hair-shearing would beimmoral, but (with her cousin across the table quietly signaling assent) she declaresthat to get on in this world you’ve got to amuse people, or shock them.

It's unclear if Bernice willgo ahead with her boast, until Cousin Marjorie eggs her into putting her bold wordsinto practice. At which point several things happen, but I wouldn’t want tospoil the story’s highly ironic ending. Let’s just call it bittersweet.

I discovered this filmedversion of the Fitzgerald story while exploring the career of the late ShelleyDuvall, best known for being absolutely terrified as Jack Nicholson goes crazyin The Shining. Duvall, who by all accounts fell into the film worldaccidentally, never had the look of a conventional Hollywood glamour-girl. Withher huge eyes, buck teeth, soft voice, and beanpole frame, she easily projectsa wallflower’s discomfort. But when she begins to show her saucy side, it’sremarkable how she sparkles, only to retreat once the deed is done back to aversion of her former self. Kudos to her, to Veronica Cartwright as CousinMarjorie and to Bud Cort (of Harold and Maude fame) as a promisingsuitor. Big congratulations to the talented Joan Micklin Silver, who in theprevious year had written and directed Hester Street, an adaptation ofAbraham Cahan’s 1896 novella about love among Jewish immigrants on the LowerEast Side. Silver is adept at establishing precise social milieus through acanny use of visuals and music. Brava!

August 6, 2024

Capturing “Thieves Like Us”

In the wake of the criticaland popular success of 1967’s Bonnie and Clyde, Hollywood was suddenlyhungry for other films that featured young lovers on the lam. I will not soonforget 1973’s Badlands, a fictionalized version of the real-life murderspree of two very young sweethearts. (That film marked the directorial debut ofTerrence Malick, and introduced many moviegoers to Sissy Spacek and MartinSheen.) In the following year, Robert Altman—best known at the time for M*A*S*H and The Long Goodbye—tried his hand at a period crime drama, ThievesLike Us. I sought it out as part of my personal farewell to the lateShelley Duvall, and found it both imaginatively conceived and surprisinglymoving.

Thieves Like Us is based on a 1937 novel that had previously beenadapted into a noir classic, They Live By Night, which marked thedirectorial debut of Nicholas Ray. While that 1948 film bowed slightlyto the moral requirements of its era, having its lovers marry and showing themale protagonist struggling with his conscience, Altman’s work is morematter-of-fact about the impulses that drive Bowie (well played by KeithCarradine) into an ongoing life of crime. Apparently, a tragic boyhood landedhim in prison at a very young age. Now he’s busted out, along with the erraticChickamaw (Altman favorite John Schuck), and they’ve teamed up with would-be-comedianT-Dub (Bert Remsen) to rob a series of local banks. This all takes place in ruralDepression-era Mississippi, and Bowie’s partners-in-crime seem to have a steadystream of local friends and relatives who’ll put them up (or put up with them)if need be.

Bowie seems happy enough togo along with the schemes of his more experienced pals. But an auto accidentputs him out of commission, and he finds himself being tended by Keechie, a shyyoung woman (Shelley Duval) who could badly use a little affection in her life.Needless to say, they quickly become lovers, and their destinies are foreverchanged. She wants a future based on happy domesticity; he’s not about to giveup the only source of income he knows. And he’s a bit proud, to be honest, thathis gang’s exploits are now making the local papers, complete with big photosand $100 bounties in store for those who bring then in, dead or alive. You can guess where all this leads.

Part of the film’s charm is Altman’scanny use of audio design. In place of a musical score, he relies on radiobroadcasts of the era to set the ongoing mood. Everyone’s life seems to revolvearound the radio, whether they’re at home or in their cars. In the course ofthe film, we hear snatches of crime dramas (Gangbusters! The Shadow!)as well as FDR’s Fireside Chats and Father Coughlin sermons. At one pointthere’s a snatch of something called The Royal Gelatin Hour. And thefilm’s big sex scene erupts while Keechie and the bed-ridden Bowie arelistening to a solemn Theater of the Air presentation of snippets fromShakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. This of course sets us up for the film’sinevitable tragic ending.

The other detail that helpscommunicate time and place is the fact that green glass bottles of Coca-Colaare present in almost every scene. But I’ll leave the final message toChickamaw, who—when all is said and done—wishes he’d paid attention in school andbecome a doctor, a lawyer, or a banker. If so, “I coulda robbed people with mybrain instead of a gun.”

August 1, 2024

Sex, Violence, Children, and “Bastard Out of Carolina”

Now that I’m reading DorothyAllison’s 1993 debut novel, Bastard Out of Carolina, I’m remembering an article I once wrote for TheHollywood Reporter, in which the TV-film version of this novel played alarge role. Allison’s work, based heavily on her own impoverished upbringing,raised many hackles because it unflinchingly depicts the sexual molestation ofits pre-teen heroine, who vividly narrates her life story. Born out of wedlockto a fifteen-year-old mother. Anney, in South Carolina, Ruth Anne (called“Bone” by one and all) suffers many indignities because she’s officially beenlabeled “illegitimate” on her birth certificate. Anney’s attempts to supply herwith a male parent end disastrously when a first step-father dies and a second,Glen Waddell, begins to physically abuse her, on the very night that her babybrother is born dead. Though over the years Anney tries to protect Bone, she’stoo devoted to her current spouse to ward off the inevitable rape and theviolence that accompanies it. Thankfully, the story ends with young Bonefinally managing to leave the family unit behind and begin her own independentlife.

Back in 2000, when I waswriting about the 1996 filmed version of Bastard Out of Carolina, it wasnot easy to find. Certainly it has an impressive pedigree. Jennifer Jason Leeis top-billed as Bone’s father; Ron Eldard plays the nefarious Glen. Also featuredin the cast are Glenne Headly, Dermot Mulroney, and a host of other Hollywoodregulars. Oscar-winning actress Anjelica Huston made her directorial debut withthis project. But the key role of Bone was played by a showbiz newcomer, JenaMalone, who was all of 12 when she was cast. (Her performance got her nominatedfor Independent Spirit and SAG awards.)

I had a long phoneconversation with Jena Malone when she was not yet 16. At the time, I wasworking on an article about children who play key roles in films that relyheavily on adult-level sex and violence. The conversations I had with childactors were interesting ones. An eight-year-old who played Mel Gibson’sdaughter in a Revolutionary War drama called The Patriot was hardly put off by the film’s graphicbattle scenes. She gleefully reported to me that “the blood is ketchup andstuff. The people who play dead get up and yell ‘Lunch!’” Still, a child psychiatrist I queried wasconvinced that, for a young person, playing a victim on screen can triggersevere reactions down the road.

Post-traumatic stress, Ilearned, can be particularly acute in young actors whose roles expose them tosimulated violence and sexual abuse. That’s partly why some parents arediligent in checking out exactly what will be happening to their kids on theset, and turning down roles they feel will compromise these young actors’ senseof well-being. Still, other Hollywood mons and dads jump at the chance fortheir youngsters to play central roles in controversial dramas. (After all,Linda Blair nabbed an Oscar nom at 14 for starring in The Exorcist.) Ionce spent an evening with a deeply religious family. They were fully convincedthat their 6-year-old daughter’s key role in a film about demonic possessionwould be a boon to all humanity.

When I chatted with JenaMalone about Bastard Out of Carolina, I was surprised by her maturity.She said that at 12 she had fully understood the implications of the story’ssexual scenes and wanted them to be accurately depicted. My thoughts? I wasglad my own young daughter would never be in the position of playing such arole.

July 30, 2024

The Paris Olympics: Parlez-Vous Cinéma?

The French have always beenvery good at blowing their own horns. The spectacular opening ceremony they stagedfor last Friday’s opening of the Paris Olympics wonderfully showcased manythings at which the French nation excels, like building the Eiffel Tower,producing daring fashion ensembles, taking on romance in all its permutations,and offending the bourgeoisie. (I was fascinated to find that day-after Internetchatter accused the festivities of insulting Christianity via an impudent hintof the Last Supper in a moment featuring drag queens.) Yes, that Seine-centricopening ceremony was long (aren’t they all?) and sometimes weird, but it had anexuberance that, to my mind, lifted it high above the ordinary. And the French,bless ‘em, were confident enough in their own cultural riches to offer primeperformance slots to two women who weren’t French at all. That’s why Lady Gagadid a number complete with feathered fans, chorus boys, and diminishingclothing. And Celine Dion, coming off of a truly horrible neurologicaldisease, used her Canadian brand of French to put a stirring musical cap on thewhole evening.

The opening ceremonies, ofcourse, were designed for the TV audience, not for those drenched multitudeswho stood in the rain watching bits of diverse entertainment (a piano solo! Thecapering of a masked torchbearer over the rooftops of Paris!) while soggyathletes sailed down the Seine on barges. But as a movie person, I couldn’thelp thinking about France’s many contributions to the wonderful world ofcinema. These were not much highlighted in a ceremony that seemed to delight inpretty much EVERYHING French. The solemovie nod I remember involved a goofy film clip featuring the Minions, thoselittle yellow critters who (as it turns out) were created and directed—and evenlargely voiced--by an actual Frenchman, Pierre Coffin. Who knew?

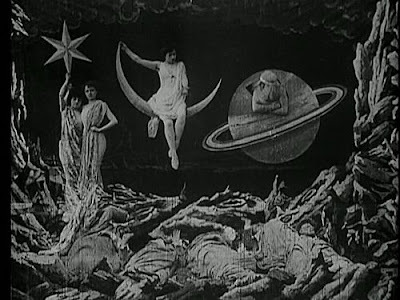

But there was no in-passingacknowledgment of such landmark French directors as Jean Renoir, FrançoisTruffaut, Louis Malle, and even (despite lots of attention to pioneering Frenchwomen) Agnès Varda. The French Nouvelle Vague (or New Wave) that hadsuch a huge impact on Young Hollywood in the Sixties went unnoticed. Even moresurprising, I heard absolutely no mention of the role played by Frenchinventors in the development of the motion picture as an artistic medium. Atrip to L.A.’s Academy Museum nicely reminds visitors where movies came from.(No, not the stork!) The wonderfully named Auguste and Louis Lumière wereFrench inventors of photographic equipment, and the short films they producedbetween about 1895 and 1905 (documenting such commonplace events as workersleaving a factory) were among the first motion pictures ever made. GeorgesMéliès, another early filmmaker born in the late 19thcentury, was not much interested in the Lumière brand of cinéma-veritérealism. Méliès, who was a magician of some repute, became entranced withthe trickery made possible by the motion picture medium. He helped create thelongstanding vocabulary of special effects cinematography, pioneering suchtechniques as multiple exposures, time-lapse photography, , dissolves,and hand-tinted color. Those of us whoremember the Apollo 11 moon-landing in 1969 surely recall seeing the frequentclips from Méliès’ Le Voyage Dans La Lune (based on Frenchman JulesVernes’ 1865 novel, From the Earth to the Moon), complete withastronauts, friendly moon maidens, and a landing that hits the Man in the Moon(splat!) in the eye.

Of course the Olympics are afestival of sports. To honor its cinema heritage, France has the annual CannesFilm Festival in spring. But there’s no question that out of this currentOlympiad will come a movie.

An update: Mea culpa! Areporter writing in the L.A. Times mentions that the opening ceremony containeda subtle (and by me unseen) reference to Méliès and other French film pioneers. Where? Ireally can’t say.

July 25, 2024

Killers of the Flower Moon: On the Page and On the Screen

I saw Killers of theFlower Moon last fall, when it first arrived in theatres. There’s noquestion that a 206-minute film makes for a lengthy sit, but I was enthralledby a story I previously knew nothing about. I was fascinated by the realizationthat a Native American tribe had, thanks to the 1897 discovery of oil on triballands, become so fabulously wealthy that by the 1920s some were buying luxurycars, fancy clothing, and jewelry, sending their children to private schools, andtraveling to Europe on vacation. It was not uncommon for them to hire whiteAmericans as housekeepers and chauffeurs.

Inevitably, this accumulationof wealth in Osage County, Oklahoma, attracted grifters and conmen of allsorts. Many were out to corner Osage riches for themselves, and there was asystem in place that made this relatively simple. Congress, in its wisdom, haddecided that the Osage were too childlike to hold onto their money withouthelp, and so a system of “guardians” was established. Needless to say, theguardians were white men from the community. And suddenly the members of theOsage tribe were dying in great numbers, with whole families wiped out, fromcauses that were never adequately investigated. The years of the killings(mostly 1921-1926) are remembered by today’s Osage as a “reign of terror,” inwhich some 60 wealthy Osage mysteriously went to their deaths.

I bring this up now becauseI’ve just finished reading the book on which the film is based, David Grann’s2017 best-seller, Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and theBirth of the FBI. I was aware from the start that virtually everyone I knewwho had read Grann’s book was disappointed by the motion picture adaptation.Upon reading Killers of the Flower Moon, I could see why. Addressing thesame historical subject matter contained in Scorsese’s film, Grann arranges it inan entirely different way. He chooses to divide his material into three“chronicles.” The first, “The Married Woman,” focuses on Mollie Burkhart, theOsage woman played memorably in the film by Lily Gladstone. Her mother andthree sisters are among those killed off by greedy white men for their oilrights, and she herself barely survives being poisoned by her own Anglo husband(Leonardo Di Caprio), who loves her, but perhaps loves money (and his nefariousuncle. William Hale) more. This material, with its twisted love story, is whereScorsese focuses.

The second “chronicle,”titled “The Evidence Man,” is devoted to Tom White, a serious-minded Texaslawman who arrives at the FBI at a time when J. Edgar Hoover is transforming itfrom the so-called Department of Easy Virtue to a serious law enforcement body.This was the era when detectives came into their own, both on the screen and inreal life. White as a character has a small role in Scorsese’s movie, nicelyplayed by Jesse Plemons. But the implications of his whole career could supporta fascinating film, perhaps a more sophisticated version of The FBI Story (a1959 James Stewart flick, heavy on heroics, that relied mightily on Hoover’s fullcooperation).

Finally, Grann spends histhird “chronicle,” in the first-person, detailing how he himself, as aninvestigative reporter showing up almost 100 years after the crimes werecommitted, uncovered new evidence and was able to trace the long-termrepercussions of the murders among today’s Native American community. As areader who’s also a writer, I found it exciting to learn how much evidence adedicated reporter can find, even decades after the fact. Maybe a documentaryis in order?

July 23, 2024

3 Women: Robert Altman’s Waking Dream

I’m told that the plot for 3Women came to Robert Altman in a dream. That must have been some dream! Hewas apparently sleeping fitfully, worried about his wife surviving a serious medicalcrisis. In his dream, he was directing Shelley Duvall and Sissy Spacek in astory about identity theft, set against the austere backdrop of the Californiadesert. Awakening, he jotted down multiple pages of notes, which eventuallyturned into a highly ambiguous screenplay.

I discovered this 1977 film (whichwas financed by 20th Century Fox in tribute to Altman’s trackrecord) while reading through obits for the saucer-eyed Duvall, a longtimeAltman favorite. It premiered at Canneswhere it won positive reviews, especially for Duvall’s performance, which wonher a Best Actress award. Mainstream audiences, though, didn’t know what to dowith it. Though the film nabbed a few accolades from critics’ societies, Oscarvoters (and the public) remained indifferent.

Altman, a master at setting ascene, begins with eerie, androgynous figures, looking something like primitivedeities. Apparently these are paintings, adorning a desert town’s walls and thebottoms of its swimming pools. The watery images give way to a sad-lookinglocal health spa, where feeble seniors are being helped into a therapy pool byyoung women in drab grey uniforms. Eventually we meet a new addition to thestaff. Pinky, played by Spacek is a recent arrival from Texas. Pinky dresses inmodest pastel-pink frocks, and responds, wide-eyed, to all the opportunitiesafforded her in this new situation.

For the first third of thefilm, it seems primarily Spacek’s story. Duvall is introduced to her as one of the most capable of the therapyassistants, and before long she’s showing Pinky her off-hours haunts andletting this very naïve girl share her cheerfully decorated apartment. It’s awhile before we realize the film’s focus has shifted to Duvall, as Millie.Seemingly confident and sociable, full of mile-a-minute chatter, she turns outto be not as socially successful as she at first appeared. In fact, she’slonely, and Pinky’s awestruck admiration of her seems to be quickly waning.

In the wake of a strongdisagreement between the two, there’s a near drowning in one of those bizarrelydecorated swimming pools. As Pinky lingers in a coma, Duvall’s Millie takes itupon herself to watch over her roommate day and night, even going so far as tolocate her parents in Texas. But fromthis point forward, nothing seems to go as we might expect. While Millie isrevealing a surprisingly maternal side, the recuperating Pinky seems to havechanged completely. Once modest, slightly childish, and a teetotaler, she now confidentlydrinks, smokes, and shows off her prowess with a pistol at a local shootingrange. Who knew?

The film is titled 3 Women,and—yes—there is a third, played by Broadway veteran Janice Rule. (She starredin the original stage production of William Inge’s Picnic, and at thetime this film was made was married to Ben Gazzara. A previous husband wasRobert Thom, the screenwriter behind Wild in the Streets, and one of thestrangest men I met in my Corman years.) Rule plays a mysterious woman, theartist responsible for all those weird images. Though significantly older thanSpacek’s and Duvall’s characters, she’s heavily pregnant by her husband, amovie stuntman who’s clearly up to no good. There’s a harrowing scene in whichher baby is delivered, in her husband’s absence by the in-over-her-head Millie.And what follows next is even stranger, with the three women transformed intoentire different people. Ah, Altman!

July 19, 2024

A Slow, Sad Remembrance of Video Master Bill Viola

Some twenty years ago, I waslooking at Baroque religious paintings at Chicago’s Art Institute when my eyewas caught by something strange. One of the paintings was life-sized, and whenI studied the female figures it depicted, I realized they seemed to be moving towardone another . . . very, very slowly.Surely, I thought, there was no such thing as a movie back in the 16thcentury. This work, despite its long-ago style, had to have been created in myown era.

And so it was. This movingpainting was made by Bill Viola, a pioneering video artist. I later learned itis called “The Greeting,” and was inspired by Italian master Pontormo’s workdepicting Mary approaching her cousin Elizabeth to confide that she is withchild. I have since sought out Viola’s strikingly mystical videos in othervenues, like L.A.’s Getty Center. One of the great evenings of my life wasspent at the Los Angeles Music Center, watching an act of Wagner’s opera Tristanand Isolde, as directed by the always-innovative Peter Sellars. As part ofthe so-called Tristan Project, Sellars invited Viola to contribute semi-abstractvideo sequences that—again in ultra-slow motion—backed the on-stage singers,contributing an otherworldly dimension to the famous love story. Other Viola workpops up in surprising places: two so-called video altarpieces are on permanentdisplay in London’s St. Paul’s Cathedral.

I was recently shocked tolearn that Viola has passed away, at age 73. Alas, he had succumbed to a longstruggle with Alzheimer’s Disease. A very sad and ironic end for someone whowas once so life-affirming. I know,because back in 2008, I had a long, fascinating conversation with Viola at hishome in Long Beach, California. Reasoning that a man who had devoted his lifeto video art would have some interest in movies, I approached him on behalf ofa project I was working on about the films of the late Sixties and earlySeventies. In that era he had been at art school in Syracuse, New York,studying the work of avant-garde filmmakers like Stan Brakhage and Maya Deren.For him and his classmates, Hollywood was a kind of enemy, and narrative film alimitation on what they were trying to achieve. And, in any case, “the big boyshad all the money.”

Still, commercial movies madea strong impression on him, beginning with his childhood viewing of KingKong. Then in 1968 Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey had a profound impact:“My brain didn’t understand it, but mybeing totally got it. And years and years later I was still living on imagesfrom that movie and the pacing of that movie.” What he describes as “the soundof emptiness” in Kubrick’s film connected nicely with his own later Zenstudies. And he never forgot 2001’s “image of the guy floating untethered out in space, and . . . what fills the theatre, fills your mind, isthe sound of his breathing. Like the breathing’s inside your head, and he’s inthe largest, most infinite space that is known to exist.”

Describing himself as someonewho lives and breathes images, Viola reminisced about what he’d taken from AndyWarhol’s cinematic experiments regarding the passage of time. But he alsolearned from commercial films like The Graduate (“I remember being aware of camera movement inthat film”), Days ofHeaven ( “Those long shots ofthose prairies, the vast emptiness of the space”) and A Hard Day’s Night (“Amainstream experimental film.”)

I’ll never forget myconversation with this fascinating man. Farewell!

Beverly in Movieland

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers