Killers of the Flower Moon: On the Page and On the Screen

I saw Killers of theFlower Moon last fall, when it first arrived in theatres. There’s noquestion that a 206-minute film makes for a lengthy sit, but I was enthralledby a story I previously knew nothing about. I was fascinated by the realizationthat a Native American tribe had, thanks to the 1897 discovery of oil on triballands, become so fabulously wealthy that by the 1920s some were buying luxurycars, fancy clothing, and jewelry, sending their children to private schools, andtraveling to Europe on vacation. It was not uncommon for them to hire whiteAmericans as housekeepers and chauffeurs.

Inevitably, this accumulationof wealth in Osage County, Oklahoma, attracted grifters and conmen of allsorts. Many were out to corner Osage riches for themselves, and there was asystem in place that made this relatively simple. Congress, in its wisdom, haddecided that the Osage were too childlike to hold onto their money withouthelp, and so a system of “guardians” was established. Needless to say, theguardians were white men from the community. And suddenly the members of theOsage tribe were dying in great numbers, with whole families wiped out, fromcauses that were never adequately investigated. The years of the killings(mostly 1921-1926) are remembered by today’s Osage as a “reign of terror,” inwhich some 60 wealthy Osage mysteriously went to their deaths.

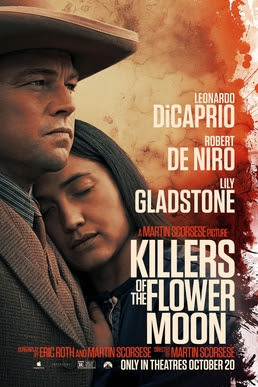

I bring this up now becauseI’ve just finished reading the book on which the film is based, David Grann’s2017 best-seller, Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and theBirth of the FBI. I was aware from the start that virtually everyone I knewwho had read Grann’s book was disappointed by the motion picture adaptation.Upon reading Killers of the Flower Moon, I could see why. Addressing thesame historical subject matter contained in Scorsese’s film, Grann arranges it inan entirely different way. He chooses to divide his material into three“chronicles.” The first, “The Married Woman,” focuses on Mollie Burkhart, theOsage woman played memorably in the film by Lily Gladstone. Her mother andthree sisters are among those killed off by greedy white men for their oilrights, and she herself barely survives being poisoned by her own Anglo husband(Leonardo Di Caprio), who loves her, but perhaps loves money (and his nefariousuncle. William Hale) more. This material, with its twisted love story, is whereScorsese focuses.

The second “chronicle,”titled “The Evidence Man,” is devoted to Tom White, a serious-minded Texaslawman who arrives at the FBI at a time when J. Edgar Hoover is transforming itfrom the so-called Department of Easy Virtue to a serious law enforcement body.This was the era when detectives came into their own, both on the screen and inreal life. White as a character has a small role in Scorsese’s movie, nicelyplayed by Jesse Plemons. But the implications of his whole career could supporta fascinating film, perhaps a more sophisticated version of The FBI Story (a1959 James Stewart flick, heavy on heroics, that relied mightily on Hoover’s fullcooperation).

Finally, Grann spends histhird “chronicle,” in the first-person, detailing how he himself, as aninvestigative reporter showing up almost 100 years after the crimes werecommitted, uncovered new evidence and was able to trace the long-termrepercussions of the murders among today’s Native American community. As areader who’s also a writer, I found it exciting to learn how much evidence adedicated reporter can find, even decades after the fact. Maybe a documentaryis in order?

Beverly in Movieland

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers