Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 11

September 24, 2024

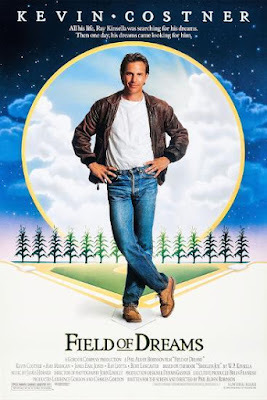

“Field of Dreams”: If You Shoot It, Will They Come?

It’s hard to imagine how manytruly idiotic projects have been launched, over the years, based on a hit movie’spromise that “if you build it, they will come.” To be honest, 1989’s Fieldof Dreams doesn’t make a whole lot of sense. Just exactly WHY do the 1919Chicago White Sox, in perennial disgrace for their role in throwing that year’sWorld Series, emerge from an Iowa cornfield because a young farmer who missesthe Sixties has constructed a baseball field on his back forty? Why does this farmer idolize baseball, and long-agoWhite Sox batting champ Shoeless Shoe Jackson in particular, to the point thathe’ll jeopardize his family’s economic future by taking direction from amysterious voice? (And, come to think of it, why does his feisty wife put upwith her husband’s fiscal craziness even though they might well find themselveshomeless in future?)

But logic is not what Fieldof Dreams is all about. It’s about dreams, and in particular about the Americanmale’s dream of a father/son bond symbolized by the idea of tossing around abaseball with your dad on a warm summer’s day. The give-and-take implicit in a simplegame of catch seems to be craved by many men. At least, it is this element ofthe film’s climax that apparently turned many male moviegoers into emotionalpuddles when Field of Dreams screened in cineplexes across America in1989. The movie attracted critics as well as audiences. It was nominated forthree Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Adapted Screenplay; in2017 it was welcomed onto the National Film Registry.

Before I rewatched Fieldof Dreams this past week, I of course remembered primarily Kevin Costner asthe dreamy farmer with father issues and a great abiding love for America’sgame. And I fleetingly remembered Amy Madigan as Costner’s supportive wife aswell as Ray Liotta (always a distinctive actor) as the shadowy incarnation ofShoeless Joe. I did not recall Burt Lancaster in a small but key role asArchie “Moonlight” Graham, an actual long-ago outfielder who played only asingle game in the major leagues before attending medical school and embarkingon a long, distinguished stint as a smalltown doctor. Lancaster’s role, thelast of his stellar career, allows him to hint that there are other kinds ofglory than those found on a baseball diamond.

I also didn’t remember that Fieldof Dreams contains a major supporting role for James Earl Jones, thelegendary actor with the basso profundo voice who left us just a few weeks agoat the age of 93. Jones played Terence Mann, a successful novelist who foundfame in the Sixties, but now contends with small-minded readers who seek to banhis books. In the course of the film, Mann’s character is discovered to have asecret passion for baseball. Eventually he delivers a long, wonderful speechabout baseball and its connection with America past and present. In theup-and-down history of our nation, says he, “the one constant through all theyears has been baseball.” It is baseballthat signifies “all that once was good, and could be again.”

The extras that accompany theDVD of Field of Dreams contain many clips of the film’s actors,producers, and writer/director Phil Alden Robinson. Almost all of them talkabout their personal passion for baseball, and share memories of ballgamesplayed with their dads. Jones is the exception: he never played catch with hisabsentee father. Still, he considered baseball a key part of his DNA, and hisjoyous performance here proves it.

September 20, 2024

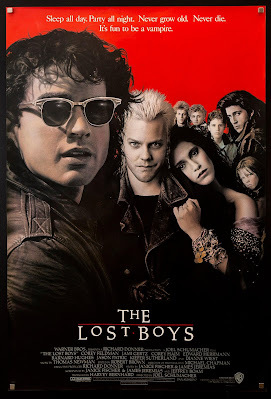

When You’re Strange: “The Lost Boys”

I recently spent five days inSanta Cruz, California, visiting members of my extended family. Though Ithoroughly enjoyed the classic boardwalk and the nearby redwoods, I didn’t spota single vampire. And now I’m just a wee bit disappointed. Perhaps I shouldexplain: last night I watched a cult classic shot largely in Santa Cruz, thoughin the film the town goes by the name of Santa Carla. The Lost Boys,directed by Joel Schumacher in 1987, is a horror film of a rather whimsicalsort. It posits that each evening the venerable beachside fun zone is overrunwith scruffy young biker types who sleep all day, hanging upside down from theceiling of a convenient seaside cave, and choose to drink something that looksan awful lot like blood.

Schumacher’s contribution tovampire lore is a fascinating one. I believe he and his writers fudged, just abit, the classic rules of vampire evolution: I haven’t run into other vampirestories in which you can remain in a half-vampire state until your first kill,with the possibility that you can return straightaway to being fully human ifthe head of the pack is somehow bumped off. This is part of the optimisticstreak that makes The Lost Boys actually endearing. The project beganwith a smart writer cogitating on the gang of “lost boys” surrounding J.M.Barrie’s Peter Pan. Living in the wild without conventional families, theseyoungsters formed themselves into a tribe that was ready for anything. And theyproved to be desperate to find themselves a mother.

All of this subtly finds itsway into a contemporary story that takes advantage of Santa Cruz’s reputationfor a laid-back post-Sixties vibe. Set against the creepy biker guys, led by aspiky-haired young Kiefer Sutherland, is a wholesome family group. Mom DianneWiest, trying to recover from a painful divorce, has brought her two sons tolive with their curmudgeonly grandfather (Barnard Hughes, who has one of thefilm’s funniest lines). Hunky Michael (Jason Patric) is clearly restless,looking for a way out of the tight-knit family unit. When a gorgeous younghippie-type in a filmy outfit (Jamie Gertz) wafts by on the boardwalk, he’s agoner. Younger brother Sam (Corey Haim) loves his brother and his dog, and justwants to live out the summer at Grandpa’s in a comfortable way. He doesn’t knowwhat he’s in for when two intense young comic-book mavens named Edgar and AlanFrog (the indispensable Corey Feldman and Jamison Newlander) decide to educatehim about vampire lore. Suddenly, when he sees his big brother start to weardark glasses indoors, Sam realizes there’s a problem afoot. Set against all ofthis is Wiest’s amiable Lucy, trying to keep her family in line while pursuingan oft-thwarted romance with a buttoned-down boardwalk shopkeeper played byEdward Herrmann.

Schumacher himself hascredited the film’s long-term success to the casting of brilliant young actorswho were just starting their careers. Though Kiefer Sutherland had already shotStand by Me, it had not yet been released when he went before thecameras in The Lost Boys. Jason Patric had previously made only onefilm, something called Solarbabies, before The Lost Boys turnedhim into a heartthrob. Teenagers Corey Haim and Corey Feldman became householdnames because of this movie, as well as best friends. They later appearedtogether several times on screen; an A&E reality series titled The TwoCoreys (2007-2008) sadly chronicles how their lives went downhill over theyears. (Haim died at age 38.) Fame, it seems, is even more dangerous thanvampires.

September 17, 2024

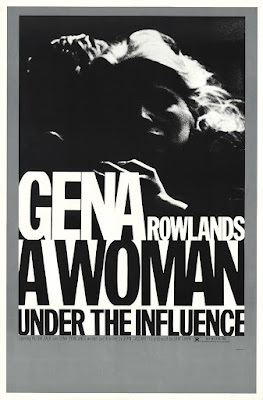

Gena Rowlands Under the Influence

The death of Gena Rowlandslast month, at age 94, gave me pause. I had always admired her devotion to herhusband, the actor and writer/director John Cassavetes. Married from 1954 untilhis death in 1989, she was an important part of his work as an indie auteur. Togetherthey collaborated on ten films, two of which (1974’s A Woman Under theInfluence and 1980’s Gloria) brought her Oscar nominations for BestActress. They also raised three children, all of whom now have acting anddirecting careers of their own. In 2004 she was featured in the popular weepie,The Notebook, as the older version of Rachel McAdams’ character, underthe direction of son Nick Cassavetes. But she also performed admirablyin the films of others, like Woody Allen’s somber Another Woman andLasse Hallström’s comedic Something to Talk About. In 2007 her voiceelevated the role of the wise Iranian grandmother in the English-languageversion of Marjane Satrapi’s marvelous animated Persepolis.

It was heartbreaking to learnthat Rowlands lived with Alzheimer’s disease for five years before she died. Thisnews reinforced my vivid memories of Rowlands coping with another mentaldisorder in A Woman under the Influence. At first it’s not clear thatthere’s anything wrong with Mabel Longhetti, other than stone-cold fury againsther husband Nick (Cassavetes regular Peter Falk). She seems entitled to beaggravated: though a loyal husband and father, Nick appears (like so many men) to be devotedabove all to his work and his work buddies. The well-liked boss of aconstruction crew, he perhaps can’t help it when the city demands he and hisguys labor all night to solve an emergency leak problem, thus forcing him tocancel on a long-planned “date night” with his pretty wife. Still, it’sparticularly oblivious of him to show up the next day with his entire crew,expecting that Mabel will host an impromptu lunch party.

The anger that’s inside Mabelcan show up in some surprising ways. When Nick is gone on that overnightemergency, she heads for a local bar, drinks much too much, and picks up awilling stranger. Then, after Nick arrives home with his work gang, she goesoverboard as a charming hostess, obsessively flattering and flirting with theguys. But it’s at a children’s backyard party that she seems to come totallyunglued, leading to a manic insistence that all the kids exercise theircreativity by shedding clothes and manners. This precipitates a chaotichomecoming by Nick, who slaps her, gets into a physical altercation withanother parent, and eventually summons a doctor with a large syringe.

We never see Mabel’shospitalization, but stick with Nick trying to hold the family (including hisown judgmental mother) in check. The film’s final act involves Mabel’s shakyreturn home, after Nick is finally dissuaded from throwing her a large surpriseparty. As some critics griped at the time, the movie is long (2 ½ hours) andultimately bleak. But it takes advantage of Cassavetes’ penchant for keepingthe camera locked in place. This makes for extended takes that give us anunflinching view of Mabel’s disintegration, as witnessed by those around her.She’s a woman whose talent for role-playing masks the fact that she doesn’tknow who she is. It’s a bold, spontaneous-seeming performance.

Cassavetes and Rowlandslargely financed and distributed this film themselves, shooting on the cheapwith faculty and students from the new American Film Institute. That’s why Iwas gratified to see the names of several of my eventual Roger Corman pals inthe crew credits. (Hi, Mike Ferris!)

September 12, 2024

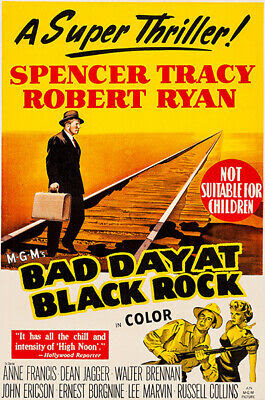

Spending a Good Evening at Black Rock

Bad Day at Black Rock is by no means a small movie. This 1955 MGM western,shot in color and Cinemascope, features three past Academy Award winners:Walter Brennan, Dean Jagger, and star Spencer Tracy. Also prominent in the filmare Oscar nominee Robert Ryan and two rising talents who would win futureOscars, Ernest Borgnine and Lee Marvin. Director John Sturges, a former editor,would go on from Bad Day at Black Rock to helm The Magnificent Seven andThe Great Escape. The film’s wide-screen cinematography beautifullyemphasizes the wide open spaces of the Lone Pine locales, and the mood isenhanced by André Previn’s haunting score.

So this is hardly a modest indie. And yet itcontains many of the elements I’ve learned to admire in B-movies. For onething, it’s short and tight, coming in at a mere 81 minutes. Locations arelimited; dialogue is clipped and to the point; tension is strong; bursts ofaction are prized. A mystery bubbles beneath the surface. There’s also, alongwith moments of dark humor, a subtle strand of meaningful social commentary.(I’m certain my former boss, Roger Corman, deeply admired this film, whichcaptures many of his own aesthetic and social values.)

Set in the Californiaoutback, circa 1945, the film begins with a passenger train arrivingunexpectedly at a rural outpost. It disgorges a stocky man in a black suit andfedora, carrying a briefcase. The lounging locals are suspicious, especiallywhen they notice the new arrival has only one arm. As played by Spencer Tracy,he is taciturn and unflappable, even when faced with a decided lack ofhospitality. He’s hard-pressed to get a room at the one hotel, even though it clearlylacks for paying guests. When he introduces himself as John J. Macreedy of LosAngeles, and explains that he’s looking for a homesteader named Komoko,everyone becomes icier still. The cowpokes and ranchers hanging around the hotellobby all seem to be sharing a secret. Down the town’s one main street, thesheriff (Jagger) appears to be drinking himself into oblivion. Theveterinarian/undertaker (Brennan) lets slip that Komoko is no more.

Managing with some difficultyto rent a Jeep, Macreedy heads over the hills toward the burnt-out mess thatwas once Komoko’s homestead. But the town’s unofficial boss, Reno Smith (Ryan)is not about to leave this intruder to his own devices. He sends the sadisticColey Trimble (Borgnine) in pursuit, leading to a taut action sequence.

It would be unfair of me tospell out precisely what happens next. Suffice it to say that eventually welearn what happened to Macreedy’s arm, why he’s so eager to find Komoko, andwho among the townfolk eventually come to his aid. I’ll say also that this iscovertly a story about the effects of racism and xenophobia, in the wake ofWorld War II. And that, after all the anger and mistrust, the film ends in amoment of modest but genuine hope for a better future.

The year 1955 was a great onefor American dramas, many drawn from the Broadway stage, including Mr.Roberts, Picnic, and The Rose Tattoo. Two of James Dean’sthree starring films, Rebel Without a Cause and East of Eden,were also released. Ironically, Borgnine’s supporting turn in Black Rock waseclipsed by his Oscar-winning good-guy role in Marty, which was alsonamed Best Picture. Though Black Rock was nominated for its script, itsdirection, and Tracy’s performance, it went home empty-handed. Still, it willlive on, in my memory banks and (since 2018) on the National Film Registry.

September 10, 2024

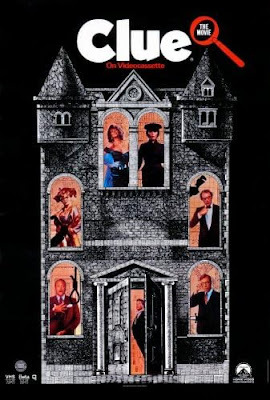

A Clue or Two

Video games are hardly mything. Old-fashioned though it may be, I continue to be fond of board games,especially those that are clever or silly. From childhood onward, I’ve lovedthe Parker Brothers game, Clue. It was apparently devised in 1943 in Britain,where it was called Cluedo, and advertised as “The Great New Sherlock Holmes’Game.” I don’t know the year of my parents’ set, the one I still have, but anote at the end of the instruction pamphlet politely tells the purchaser that“any question regarding the rules of ‘Clue’ will be answered gladly if a 3 centstamp is enclosed.”

Clue, for anyone who doesn’tknow it, comes with a gameboard presenting the layout, room by room, of anEnglish country manor. There’s a ballroom, a kitchen, a conservatory, a diningroom, a billiard room, and a study, along with a few secret passageways. In myparents’ version, all these rooms are shown from above in sketch-like fashion:the billiard table once baffled me, and I decided it was a kind of very grandbathtub, with various round things floating in it. As a matter of fact thereare no bathrooms at all in this stately home, nor bedrooms, for that matter.But we’re told that poor Mr. Boddy has been murdered. The job of the gameplayers is to figure out (via the cards in players’ hands) in which room the murder occurred, and withwhich weapon (a rope? a knife? a candlestick?) And of course, who was themurderer: the dashing Colonel Mustard? The glamorous Miss Scarlett? Wise oldProfessor Plum? The dowager known asMrs. Peacock? What I’ve discovered on the invaluable Wikipedia site is that thegame has had many permutations over the years, with—for instance—England’sReverend Green turning into a middle-aged businessman, then (in the most recentAmerican editions) a handsome playboy.

I’ve been thinking about thegame of Clue ever since I saw, this past summer, a presumably Broadway-boundproduction of a stage version that is both very silly and a great deal of fun,with lots of mistaken identity and an elaborate twist ending. This new play isan homage both to the game and to a movie that came out in 1985 and is stillremembered fondly, at least by some. (Best in-joke in the play: as thecharacters are running madly from room to room in pursuit of the killer,someone says, “Who designed this house anyway? Answer: The Parker brothers.)

That 1985 movie was blessedwith a lively cast, including Eileen Brennan as Mrs. Peacock, Madeline Kahn asMrs. White, Christopher Lloyd as Professor Plum, Michael McKean as Mr. Green,Martin Mull as Colonel Mustard, and the toothsome Lesley Ann Warren as ano-better-than-she-should-be Miss Scarlett. (One of the film’s best mysteries:how does her VERY low-cut dress keep from falling down?) There’s also Tim Curry(he of the Rocky Horror Picture Show) as a complicated new character at thecenter of the plot. All seem to be having a grand old time spoofing the murdermystery films of yore. But there’s also a gimmick that sets Clue apart.Three different endings were filmed, each of which identifies a differentmurderer, with different methods and motives. Presumably, audiences weresupposed to be so jazzed by the idea of seeing variant endings that they’d showup at the cinemaplex more than once. It didn’t happen, but when the film cameout on video, all three endings were available to be seen. And some people nowregard this crazy little flick as a cult classic.

September 6, 2024

Stan Berkowitz, Bat Scribe

I first met Stan Berkowitz inthe rather grubby offices of the UCLA Daily Bruin. I was a gradstudent who thought it would be fun to write about movies for my fellowcollegians, while continuing to crank out serious literary papers for my profs.And Stan was my oh-so-amiable editor. Decades later we re-connected, when heshowed up at one of my book signings. I found out then that—like me—he’d eventuallygone Hollywood. In fact, he insisted that, post-college, he was a candidate forthe same Roger Corman job that ultimately changed my life. As a graduate ofUCLA’s film school Stan doubtless had far better credentials than I did formaking B-movies, Corman-style. After all, he was a budding filmmaker, not anEnglish major. Still, I was female, which doubtless helped me get Roger’s nod.Stan instead found work with Russ Meyer, the auteur behind such deathlesssexploitation flicks as Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! Meyer, unlike Roger, didn’t want womendoing challenging work in his offices or on his sets. He wanted them in frontof the cameras, flaunting their “Guns of Navarone” bazooms, leaving hisall-male crews in a permanent state of arousal.

Following his Russ Meyerstint, Stan eventually found his way into television, He started out writingfor crime dramas like T.J. Hooker, then eventually discoveredhis niche in the wonderful world of superheroes, crafting shows like BatmanBeyond, The New Batman Adventures, Superman: The Animated Series,and Justice League Unlimited, ending up with two Emmys on his shelf. Nowthat he’s old enough to be considered an expert in his field, he’s decided toshare his wisdom in a charming little volume called Beyond the Bat: Secrets of a Superhero Scribe.

In thirteen lively essays, Stanbares his insights on how to succeed in Hollywood. He describes working with acloset racist, trying to create a show for Middle Eastern audiences thatfeatured Muslim superheroes, and struggling to incorporate Old Testamentstories into an animated series for the Christian market. (That chapter istitled: Written by Stan Berkowitz . . . and God.”) He dishes about what it’slike to butt up against a superstar’s vanity. (William Shatner, here’s lookingat you!) In one hilarious chapter, he reveals how to get attention foryour student film. This involves a curvaceous unclad lass and a whole lot ofdonkeys.

Chapter 3, titled “The GreenGroup,” struck a chord with me by merging a story from Stan’s early life with adiscussion of why some people are attracted to superhero characters. Back inthe first grade, when learning to read was at the top of the agenda, Stan’steacher automatically assigned “the little bespectacled kids” to the BlueGroup, on the assumption that they would be fast learners. Stan, though, wasamong the “big, oafish-looking kids” stuck at the Green table, where they wereclearly being identified as slow. Fortunately, he and his buddy Gregory (also aGreen Group-er) fought back, via their parents, and eventually got moved up tothe smart kids’ table. The episode convinced young Stan to distrust thejudgment of those in power, and his anti-authoritarian streak has stayed withhim from that day to this. No wonder he has gravitated toward characters likeBatman and Superman who are essentially vigilantes, going over the heads ofelected officials to clean up crime and save the world on their own terms.

If you think the world of TVproduction is glamorous, Stan provides a healthy reality-check. And his book, amusinglyillustrated by Dan Riba, is a ball to read.

September 3, 2024

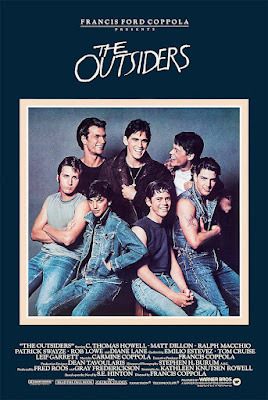

From Your First Cigarette to Your Last Dying Day: “The Outsiders”

When I was growing up, youthcliques and gangs were a hot topic. West Side Story made it big onBroadway in 1957, and became a must-see film in 1961. It was five years laterthat S.E. Hinton (Susie to her friends) published a Young Adult novel called TheOutsiders. It looked squarely at the lives of teenagers who, because oftheir looks or family situations, were regarded as social outcasts in theirOklahoma hometown. In the world of this story, teens are divided into twogroups. The Socs (pronounced “soshes”) were more affluent, dressed better, andhad cool cars with fins. The Greasers worn grubby jeans and T’s, startedsmoking at a very young age, and didn’t have much use for school. Hinton—who,remarkably, published the novel when she was sixteen—empathized almost entirelywith the Greasers, whose underlying pain and sensitivity she understood. Thenarrator of her novel, Ponyboy Curtis, is a fourteen-year-old who—in theabsence of parents—shares strong bonds of loyalty with his three olderbrothers. Though he's at the fringes of some brutal situations, like a rumblein a local park, he’s basically a good kid who’s polite to girls, lovessunsets, and ruminates over a poem by Robert Frost, “Nothing Gold Can Stay.”

When I was growing up, youthcliques and gangs were a hot topic. West Side Story made it big onBroadway in 1957, and became a must-see film in 1961. It was five years laterthat S.E. Hinton (Susie to her friends) published a Young Adult novel called TheOutsiders. It looked squarely at the lives of teenagers who, because oftheir looks or family situations, were regarded as social outcasts in theirOklahoma hometown. In the world of this story, teens are divided into twogroups. The Socs (pronounced “soshes”) were more affluent, dressed better, andhad cool cars with fins. The Greasers worn grubby jeans and T’s, startedsmoking at a very young age, and didn’t have much use for school. Hinton—who,remarkably, published the novel when she was sixteen—empathized almost entirelywith the Greasers, whose underlying pain and sensitivity she understood. Thenarrator of her novel, Ponyboy Curtis, is a fourteen-year-old who—in theabsence of parents—shares strong bonds of loyalty with his three olderbrothers. Though he's at the fringes of some brutal situations, like a rumblein a local park, he’s basically a good kid who’s polite to girls, lovessunsets, and ruminates over a poem by Robert Frost, “Nothing Gold Can Stay.”Following his acclaimedrelease of two Godfather films and Apocalypse Now,director-producer Francis Ford Coppola turned his talents to The Outsiders,after a librarian and her students at Lone Star Elementary School in Fresno,California brought the novel to his attention. Now his goal was to find atroupe of very young actors who could embody Hinton’s characters on thescreen. C.Thomas Howell, then fifteen, appealingly played Ponyboy. Hisbrothers—the tortured Dally and the take-charge Darrel—were Matt Dillon andPatrick Swayze. Other rising young actors in the cast were Rob Lowe, EmilioEstevez, and (in a small part) Tom Cruise. A key role, that of a very youngGreaser who proves himself both a hero and a martyr, was played by RalphMacchio, just before he became The Karate Kid. (He apparently was 20 at thetime, but convincingly looks about 13.) The film’s final moments, in which aclose-up of Macchio is superimposed upon an image of Ponyboy writing his storyis either hugely poignant or hugely corny, or both at once.

As a movie, The Outsiders makesan interesting contrast to the much-beloved West Side Story. Itsrivalries are purely social rather than ethnic. West Side Story ofcourse pits Puerto Rican immigrants against white kids whose ancestry isprobably not far removed from Ellis Island. But in The Outsiders thedivide is almost entirely along economic lines. And, of course, there’s nosinging and dancing in this film. Being a Greaser doesn’t seemnearly as much fun as being a Jet. The rumble in which most of the charactersparticipate is less picturesque than grubby, fought in the mud during a drivingrain.

At my L.A. public high schoolthere was not the kind of stark social divide portrayed in the film. Though Inever heard anyone called a Greaser, we definitely had Soshes, who vied to gainmembership in exclusive social clubs. A more innocent version of the kind ofdivide portrayed in The Outsiders shows up in both the stage (1971) andthe film (1978) versions of a box-office hit, Grease. Hinton’s novel could have been aninspiration for that show, but I suspect there was something in the culturethat inspired both projects. Ironically, a version of The Outsiders landedon Broadway in 2024, taking home the Tony Award for best musical.

August 30, 2024

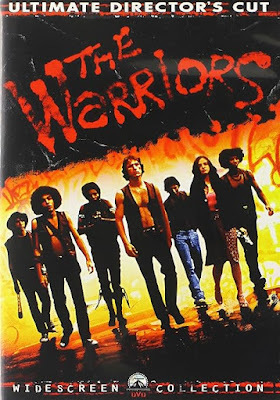

Heading Home with “The Warriors”

New York, New York, ahelluva town

The Bronx is up, and the Battery's down

The people ride in a hole in the groun'

That’s the deathless lyricfrom On the Town, the Leonard Bernstein/Comden & Green musical delight that was ahit on Broadway and later on the silver screen. There are a lot of referencesto underground travel in this show, including the fact that its leading lady isfirst seen on a subway poster proclaiming her as the current “Miss Turnstiles.”(Yes, for years pretty New Yorkers really vied to be named Miss Subways.)

No question that a lot ofgreat movies are set on the sidewalks of New York, whether we’re talking aboutromantic comedies like Breakfast at Tiffany’s or crime dramas like MeanStreets or Woody Allen’s quirky valentines to his native city. And theworld under the sidewalk is featured in some explosive thrillers,including The Incident (1967) and The Taking of Pelham 123 (1974and 2009), where much of the action is confined to a subway car under siege.But I just saw a movie that should take the prize for its continual focus onthe ins and outs of the New York transitsystem.

Walter Hill’s The Warriors(1979), today regarded as a cult classic, has an unusual originstory. The novel on which it is based was inspired by historical writings fromancient Greece, Xenophon’s Anabasis. This is an account of a Greek army,known as the Ten Thousand, and its desperate struggle to return home from abloody expedition in Persia. How times have changed! Both the Sol Yurick noveland the film are set among street gangs in New York City. There’s ameant-to-be-peaceful confab in the Bronx, at which a charismatic leader namedCyrus (a nod to the story’s classical roots) outlines a plan for the gangs tojoin forces in order to outnumber the cops and dominate the city. But, uh oh!,Cyrus is suddenly shot dead by an unhinged punk—who manages to spread the wordthat the leather-vested Coney Island gang called the Warriors are responsible.

The nine Warriors on whom thestory focuses want only to get back to their home turf in Southern Brooklyn,some thirty miles away. That’s why, late at night, they’re in and out of subwaystations, desperately trying to evade the other gangs that are bent onpunishing them for something they didn’t do. Along the way they get accosted,get tricked, sometimes make foolish choices, and end up with a young womanwho’s as tough as they are. It’s an odyssey that’s sometimes funny, sometimesterrifying, but always exhilarating to watch.

Director Walter Hill decidedearly on that a purely realistic story about street gangs wouldn’t work. Hischoice was to amp up the film’s slightly futuristic dark humor, especially seenin the costuming of the various gangs. Though the central nine lookappropriately tough in their leathers, other groups go in for more outrageousgarb. Like the bat-swinging group who dress in vintage baseball uniforms. Andthe hippie types, and the ones in bright orange karate-gi. And (my favorites)the gangsters in white face paint who look like French mimes.

A comic book fan, Hill addedto the director’s cut scene-ending “splash panels” in which the live figuresbriefly turn into drawn images. They add to the larger-than life sense of atimeless story that’s mostly about going home. The sight of the ocean at theend of their long journey is moving indeed. Kudos to Hill and to the noviceactors involved with this low-budget gem.

August 27, 2024

Tevye and Tradition: “Between the Temples”

These days cultural blendingseems to be the thing among romantic couples. Certainly, I have no objection totrue love in whatever form it takes. But I’m a bit weary of movies about NiceJewish Boys who seem all too eager to cast off their family traditions in orderto wed someone from an entirely different background. (Nice Jewish Girls, though,seem to be left high and dry—and then get to be the subject of snide jokes.)“Jewish nebbish falls for pretty blonde shiksa” is of course the premise of thevery popular Meet the Parents, which came out in 2000. Twenty-threeyears later, we had You People, which begins with Jonah Hill’scharacter, surrounded by family, celebrating the ritual of Rosh Hashanah, thenquickly segues into his falling for a handsome African-American woman whoseparents (one is Eddie Murphy) are devotees of the Nation of Islam. I didn’tstick around to watch how love conquers all, but the cultural stereotyping onboth sides didn’t strike me as all that amusing.

I’m glad that the new Betweenthe Temples doesn’t depend on the same old tropes. Yes, it’s about anunlikely relationship, but one that deeply respects Jewish tradition, thoughcertainly in an unconventional way. I’ve heard this Sundance favorite describedin terms of the age disparity in Harold and Maude, but the imbalancebetween the two leading players in Between the Temples, JasonSchwartzman and Carol Kane, isn’t nearly so large. Still, she was hiselementary school music teacher ‘way back when. They reunite purely byhappenstance. He’s now the cantor at Temple Sinai, where the congregation isremarkably supportive of his inability to sing ever since his wife (describedas a novelist and an alcoholic) died in a tragic sidewalk accident. As CantorBen mourns and mopes, Carla O’Connor (née Kessler) appears in his classroom andinsists she be accepted as a bat mitzvah student. (As a “red diaper baby,” bornto parents proud of their atheism, she loved attending her classmates’ bar mitzvah ceremonies, but never was allowed topursue a similar coming-of-age ritual for herself.)

The relationship between Benand Carla is an increasingly odd one, but I like the fact that it’s based ontheir mutual enthusiasm for Jewish ritual, though it can be argued that Carla(for one) is more caught up in the beauty of traditional cantorial music thanin actual faith. Faith, in fact, seems a complex matter for everyone in the story.I was struck by the fact that all the families portrayed in the film defystereotype. Perhaps the character who most stubbornly clings to tradition isBen’s mother’s longtime romantic partner, a woman whom he considers a secondmom. She’s a Manila-born convert to Judaism who chairs major synagogue events,professes that Jerusalem is her true home, and is quick to condemn anything shefeels violates the minutiae of the religious ritual. (She’s played withferocity by Dolly de Leon, so memorable in 2022’s darkly comic Triangle ofSadness.)

I don’t want to suggest that Betweenthe Temples works perfectly. Cantor Ben’s behavior at a key family shabbatdinner is so out of kilter that I just can’t buy it as a set-up for the film’s sweetbut highly eccentric ending. But Jason Schwartzman is effectively screwed up asBen, and it’s a delight to watch a leading screen performance by Carol Kane,whom I’ve loved ever since her Oscar-nominated role in Hester Street backin 1975. I’m not sure what Tevye would have thought of this unorthodox paean to“tradition,” but I’m glad I checked it out.

August 23, 2024

The Pleasures of Re-Reading Pauline

This was the year I watched astage revival of Funny Girl, listened again to the original castrecording, and then re-visited the 1968 Funny Girl film adaptation thatwon Barbra Streisand her Oscar. Honestly, I am not among those who adoreStreisand as a singer: her choice of material is always terrific, but for meshe has a tendency to work too hard at opera-worthy climaxes that would bebetter served by gentler treatment. Still, I find myself more and moreimpressed by her acting smarts. I know her original aim was to be an actress,not a singer, and in revisiting several of her old films I see a real superstartalent at work.

Which made it fun for me toopen this week’s New Yorker and discover it was an archival issue,featuring reviews and articles from years gone by. Naturally, I turned right tothe Current Cinema section, and discovered that “current” applied to the year1968, when Pauline Kael was the movie reviewer in residence. Kael was alwaysworth reading, even when you didn’t agree with her.. A journalistic powerhouse,she loved movies so fervently that she could make you love them too. (It didn’talways work: On the strength of her lively prose, I actually went to seemediocre movies like the 1976 King Kong, in which a giant ape curiouslychecks out the bosom of a very young Jessica Lange.) Perhaps Kael’s greatestcoup was convincing the American public that Bonnie and Clyde was afull-fledged masterpiece. Newsweek’s Joe Morgenstern, on the strength ofher recommendation, watched the film a second time, then wrote a rave thatfully rescinded his previous dismissal of it as a minor gangster flick. I’msure he was not the only critic persuaded by Kael to rethink a dismissivereview.

The Kael review thatsits open on my desk is from September 28, 1968, and it’s wholly devoted to thefilm version of Funny Girl. Like me,Kael is blown away not by Streisand’s singing but by her acting chops. Shestarts by assessing the whole meaning of stardom: “There’s hardly a star inAmerican movies today, and if we’ve got so used to the absence of stars that weno longer think about it much, we’ve also lost one of the great pleasures ofmoviegoing: watching incandescent people up there, more intense and dazzlingthan people we ordinarily encounter in life, and far more charming than theextraordinary people we encounter, because the ones on the screen are objectsof pure contemplation . . .” (Thethought goes on for several more lines; I don’t think anyone else can conquerthe run-on sentence the way Kael can.)

Kael emphatically placesStreisand among those “wisecracking heroines, the clever funny girls” who oncebrightened the screen in the thirties and forties. Among them she mentions JeanArthur, Claudette Colbert, Carol Lombard, Ginger Rogers, Rosalind Russell,Myrna Loy, “and all the others who could be counted on to be sassy and sane.”By the same token, she discovers in Streisand (during the movie’s lugubrioussecond act) “an aptitude for suffering” that those clever actresses lacked:“Where they became sanctimonious and noble, thereby violating everything we hadloved them for, she simply drips as unself-consciously and impersonally as atrue tragic muse.”

If Kael loves Streisand, sheunequivocally hates the rest of the film, especially Omar Shariff as her loveinterest, gambler Nicky Arnstein. As she points out, “If shady gamblers are notgoing to be flashy and entertaining, what good are they as musical-comedyheroes?” Good question, Pauline!

Beverly in Movieland

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers