Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 5

April 18, 2025

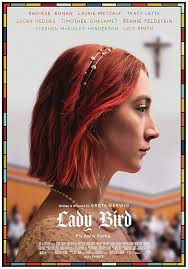

Leaps of Faith: “Lady Bird”

Wasting time on the Internet, I spotted a recent run-down of the 25 all-time best religious movies. I expected the list would contain a lot of Bible epics as well as faith-based old clunkers like The Nun’s Story and Going My Way. (Yes, both have their charm, but they seem awfully far away from life as we know it in the 21st century.) Instead, what I saw was an intelligent cluster of films in which religious faith and religious affiliations of multiple sorts take center stage, even if the central characters are grappling with religion rather than simply believing.

The list contains some oldies, like Black Narcissus (1947) as well as Ingmar Bergman’s astonishing duo from 1957, Wild Strawberries and The Seventh Seal. Some of the choices reflect religious traditions other than our familiar ones: see Atanarjuat The Fast Runner, a 2001 prize-winner from Canada that meticulously reflects Inuit culture and language. The luminous Ida, a 2013 Polish film about a nun-to-be who uncovers her Nazi-era past, is a natural for this list, but I hadn’t expected to find Minari or 12 Years a Slave or There Will Be Blood, all of which do in fact have something to say about faith. Of course I was gratified to see the great Schindler’s List in a place of honor. But the inclusion that surprised and pleased me most was that of a film I recently watched for the second time, Greta Gerwig’s Lady Bird (2017).

Lady Bird, which apparently hews closely to writer/director Gerwig’s own early life, is the story of a seventeen-year-old girl finishing up high school in Sacramento, California. (She’s played with conviction by Saiorse Ronan, who was 23 at the time.) Lady Bird is a proudly independent thinker who has given herself a new jazzy name in place of the much more predictable one with which her parents gifted her at birth. But despite the fact that she yearns to boldly enter the adult world, she’s got to finish out her classes at a benign but deeply conventional Catholic high school, where her teachers are priests and nuns. She auditions for the school play, struggles with math, and occasionally butts heads with visiting anti-abortion speakers, while also hanging out with her best pal, falling in and out of love, (with both Lucas Hedges and Timothée Chalamet) and pretending that she lives in a mansion-like local residence instead of a slightly shabby tract home.

As Lady Bird sees it, the biggest cross she has to bear is her mother, a kind-hearted but outspoken nurse who struggles to do what’s best for her headstrong daughter. Mom (Laurie Metcalf) is the practical member of the family, unlike Dad (Tracy Letts), an out-of-work dreamer who would deny his child nothing. Lady Bird has her heart set on an east-coast college (in “a city with culture”) and Dad somehow scrapes together the financials. But it’s only when she’s far from home, and dealing with an acute physical and emotional crisis of her own making, that Lady Bird comes to recognize how much she relies on both an actual home and a spiritual one. For the first time, she reverts to her birth name (Christine) and enters a church of her own volition.

It’s a simple but wholly convincing story, anchored by strong performances and Gerwig’s sure hand on the helm. Ultimately it was nominated for 5 Oscars, two for Ronan’s and Metcalf’s work and three for Gerwig in her various functions. Alas, it won none of them. Moonlight, Manchester by the Sea, and the ill-faced La La Land were the big winners.

April 15, 2025

Cinema and the City: New York, New York

I’m newly back from New York City, a place where you’d think the locals would look down on Hollywood. New Yorkers, after all, have Broadway, as well as some of the world’s best museums and attractions. Yet Hollywood loves making movies about New York City, even giving them evocative titles like Manhattan and New York, New York. In films, New York City seems made for romance—see everything from Splash (where a mermaid comes ashore in front of the Statue of Liberty) to Moonstruck to You’ve Got Mail. And of course there are celebrated TV series like Sex and the City, in which every central character is hot, funny, and out looking for Mr. (or Ms.) Right.

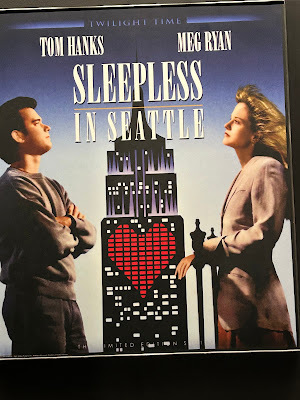

I’m newly back from New York City, a place where you’d think the locals would look down on Hollywood. New Yorkers, after all, have Broadway, as well as some of the world’s best museums and attractions. Yet Hollywood loves making movies about New York City, even giving them evocative titles like Manhattan and New York, New York. In films, New York City seems made for romance—see everything from Splash (where a mermaid comes ashore in front of the Statue of Liberty) to Moonstruck to You’ve Got Mail. And of course there are celebrated TV series like Sex and the City, in which every central character is hot, funny, and out looking for Mr. (or Ms.) Right. What I learned on my most recent trip to the Big Apple is that New Yorkers too are secretly infatuated by the lure of Hollywood. They support funky little neighborhood cinemas, and gather in local eateries for Oscar watch parties. They’re proud of landmark locations like the exterior of Carrie Bradshaw’s Sex and the City apartment on Perry Street in the West Village. If you visit the museum near the top of the Empire State Building, you’ll find yourself surrounded by reminders of how many films include the famous skyscraper in pivotal moments. There are tearjerkers like An Affair to Remember, in which an attempted meeting at the top of the building leads to near tragedy. (The famous Cary Grant/ Deborah Kerr scene was to be mirrored, decades later, by the romantic climax of Sleepless in Seattle.) There’s also a joyous dance number in the World War II classic, On the Town, that takes place on a soundstage re-creation of the building’s observation deck.

But of course the most famous use of the Empire State Building (or a Hollywood facsimile thereof) occurred back in 1933 when a giant ape climbed the skyscraper with Fay Wray in its arms, only to be shot down by a passel of buzzing biplanes. Today the building’s museum can’t get enough of King Kong: there are posters and models, and you can pose looking horrified while in the grip of the ape’s enormous fist. (I admit that I couldn’t resist trying it out.)

Manhattan’s Lower East Side, where generations of immigrants have crowded into tenements while trying to pursue their own American dreams, also has movie and showbiz connections that go back generations. This slightly squalid but picturesque area is home to a cramped little shop called Orchard Corset. It’s been around since 1949, and in the same family since 1968, but these days it doesn’t cater solely to buxom mamas from the neighborhood. This is the place from which none other than Madonna orders her sexy custom bustiers. And Orchard Corset is also beloved by theatrical costume designers, who count on the shop to supply period-appropriate undergarments. Remember the 1950s-era torpedo bosoms featured in the TV series, Mad Men? Where do you think those imposing bras were found? (Improbably, Orchard Corset also does a lively mail-order business from a site in Wenatchee, Washington.)

Visitors to the Lower East Side would be well advised to check out the Lower East Side Tenement Museum, where you can book tours of what once were the cramped little quarters of Jewish and Italian immigrants. What’s special is that these tiny apartments reflect the actual daily lives of specific well-researched families. In one flat, circa 1935, the children’s bedroom reflects a fascination with Hollywood glamour. On the wall over a young girl’s bed you can see vintage images of her movieland favorites: a very young Katharine Hepburn and Joan Crawford.

April 11, 2025

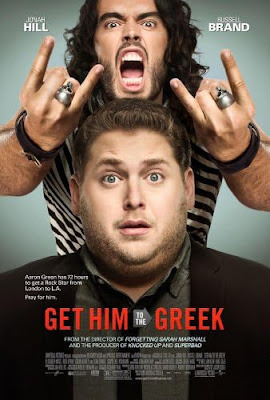

Get Him To the Greek: Harry Belafonte and Other Al Fresco Stars

Last weekend I toured Griffith Park’s venerable Greek Theatre, courtesy of the good folks at the L.A. Conservancy. Opened in 1931, with a mandate to bring culture to Angelenos, this outdoor venue now boasts 5780 seats. This makes it a small cousin to the colossal Hollywood Bowl, which seats some 17,500 music-lovers. We toured the stage, much changed from its early days, as well as the hallways where some famous acts of recent years have left their mark. And, in the distance, we spotted the hills where so-called “tree people” used to enjoy free access to the entertainment.

These days, the Greek is primarily a pop music venue. It has also been featured in movies, like 2010’s Get Him to the Greek, a goofy Judd Apatow-produced comedy featuring Russell Brand as a free-spirited rock star and Jonah Hill as the recorder exec pressed into service as his chaperone. For the 2018 version of A Star is Born, the Greek was the stage on which Lady Gaga and Bradley Cooper performed the Oscar-winning “Shallow.”

But I remember the Greek in a different mood. No, I don’t date back to the time when troops of ersatz classical nymphs frolicked on stage for the delight of theatregoers. But in the era (1952-1975) when impresario James A. Doolittle booked acts, I was taken by my parents to see some very classy entertainments from far-flung places. Here’s what I remember: Britain’s venerable D’Oyly Carte company performing Gilbert and Sullivan’s HMS Pinafore. The Grand Kabuki from Japan. The National Theatre of Britain staging an Elizabethan-style all-male production of Shakespeare’s As You Like It. The Comédie Française presenting Molière’s Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme in French, which was a very nice pay-off for my years of high school français. (My mother pointed out Maurice Chevalier in the audience.)

But I mainly associate the Greek Theater with the bi-annual summer visits by Harry Belafonte in his prime. His show, featuring singers, dancers, and a small group of musicians, was always a fabulous spectacle. He even followed up his best-selling Belafonte at Carnegie Hall live album with Belafonte at the Greek. My mother was such a fan that she saw each of his shows twice, once with my father and once with my younger sister and me. One year, when we arrived early, she’d scouted out the underground lot where headliners parked their cars. She stationed us near the exit, just in time to see the great man himself emerge. We chatted briefly, and he complimented me on the party dress I was wearing. Proudly I told him, “My mother bought it on sale.” (Behind me, Mom turned beet red.)

Belafonte, as I was to learn over the years, had many talents. In early films like Carmen Jones, which didn’t always require him to sing, he was a handsome leading man, engaged in thwarted romances and dangerous doings. Later, teaming with longtime pal Sidney Poitier who also directed, he did a nifty Brando-as-the-Godfather imitation in a ghetto crime comedy called Uptown Saturday Night (1974). In his last film, 2018’s Blackkklansman, he performed for Spike Lee as an ageing activist, a role that meshed nicely with the passions that animated his private life. To my surprise, he gets little recognition at Washington’s National Museum of African-American History and Culture. Though, in the section of the museum dedicated to entertainers, the cover of his Calypso album can be found, there’s no display case dedicated to his career. But a fiery Belafonte quote is on display at the museum connected with the Statue of Liberty: “Bring it on. Dissent is central to any democracy.”

April 8, 2025

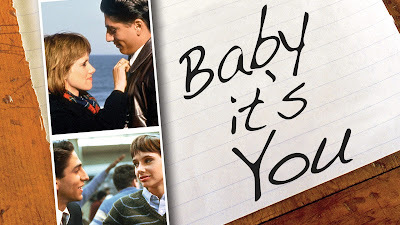

When We Were Young: “Baby, It’s You” and “The Big Chill”

A funny thing about the year 1983: filmmakers who were not so young as they used to be were now looking back on their coming-of-age years, the tender and turbulent Sixties. John Sayles, recently graduated from making horror flicks for Roger Corman, shot in 1983 his first studio movie, a coming-of-age romantic comedy called Baby, It’s You. Based on a memoir of sorts by Hollywood honcho Amy Robinson, it begins in 1966 in true Sayles territory: Trenton, New Jersey. Jill Rosen (an adorable Rosanna Arquette) is a smart and sassy high school senior who gets good grades and nabs the lead in the school play. Into her life comes Sheik (Vincent Spano), an Italian kid from the other side of the tracks who can’t exactly be called a greaser because he idolizes Frank Sinatra and dresses like a suave man about town. Opposites attract, but though Jill tempts fate by secretly dating this high school drop-out, she manages to move on when she gains admission to her dream school, the tony Sarah Lawrence.

Cut to the following year: Jill has traded in her short skirts and knee socks for hippie garb, discovered pot and the pill, and otherwise explored life beyond the purview of her solidly upper-middle-class parents. On a spring-break trip to Miami she rediscovers Sheik, now dreaming of a showbiz future but basically washing dishes in a hotel kitchen. The attraction is still there, though in other ways she’s evolved. We suspect there’s no future for their relationship, but a sweet ending (one that makes use of Sheik’s favorite song, “Strangers in the Night”) shows how much they continue to mean to one another, come what may.

It's an appealing film, though hardly a deep one, with its nostalgia element heightened by a soundtrack crammed with oldies like “Wooly Bully.” (I can’t resist mentioning that it was The Graduate that in 1967 began the trend of using pop music to establish the mood of an era.)

After he left the Roger Corman fold, Sayles’ very first film was Return of the Secaucus Seven (1980), a small but influential indie about a reunion of Sixties activists, all just turning thirty, a decade or so after their graduation from college. This low-budget gem (which Sayles himself described to me as using the low-budget Corman trick of making do with what you have on hand) was critically acclaimed for capturing the spirit of an era. It seemed to kick off a host of reunion movies, the most potent of which was Lawrence Kasdan’s hugely popular The Big Chill. Like Baby, It’s You, this film looks back on the politics and culture of the Sixties, but from the perspective of campus friends who are now older, but not necessarily wiser, than they were when they linked up at the University of Michigan. Within the framework of a weekend spent in a large house following the suicide of a close friend, The Big Chill examines successes, dreams, and particularly regrets, in a way that is sometimes poignant and sometimes funny.

The cast of The Big Chill is part of its strength. Writer/director Lawrence Kasdan, coming off the huge success of his 1981 thriller Body Heat, had access to some of Hollywood’s brightest young talents. Among the film’s stars are William Hurt (who’d scored in Body Heat), Jeff Goldblum, Kevin Kline, and Glenn Close, in only her second film. The DVD version I watched includes a years-later interview with cast and crew, highlighting how the ensemble cast, isolated in a South Carolina town, found ways to strengthen their sense of longstanding camaraderie.

April 4, 2025

Spheroids and Triangles: "Challengers"

When the big new releases of 2024 came out, one that slipped past me was Luca Guadagnino’s tennis film, Challengers. This erotic triangle featuring a sexy young female tennis whiz and the two former best friends who lust after her seemed like an interesting departure from Guadagnino’s 2017 hit, Call Me By Your Name. Not that I was entirely entranced by the coming-of-age same-sex romance that gave us an eyeful of Timothée Chalamet—playing a sensitive young man awakening to his own budding sexual urges—clambering all over the golden-hued torso of Armie Hammer. It all seemed, frankly, a bit lugubrious, but critics and audiences clearly were swooning.

When the big new releases of 2024 came out, one that slipped past me was Luca Guadagnino’s tennis film, Challengers. This erotic triangle featuring a sexy young female tennis whiz and the two former best friends who lust after her seemed like an interesting departure from Guadagnino’s 2017 hit, Call Me By Your Name. Not that I was entirely entranced by the coming-of-age same-sex romance that gave us an eyeful of Timothée Chalamet—playing a sensitive young man awakening to his own budding sexual urges—clambering all over the golden-hued torso of Armie Hammer. It all seemed, frankly, a bit lugubrious, but critics and audiences clearly were swooning. I was curious to see Challengers because the dynamic among the three leads promised to be intriguing and because I wanted to see how Guadagnino handled female sexuality at his film’s center. Certainly he has put together an attractive cast, with the gorgeous Zendaya rotating between a charmingly boyish Mike Faist (he was Riff in Spielberg’s take on West Side Story) and an appealingly scruffy Josh O’Connor (with an American accent that far removes him from his role as Prince Charles in The Crown). The idea is that they all meet on the junior tennis circuit where the two very young men have just won a championship as doubles partners and Tashi is an extraordinary young player with a scholarship to Stanford.

Then time passes, and Guadagnino gets fancy, jumping between various eras we can distinguish mostly because Tashi’s hair gets shorter and Art’s blond curls disappear. The jumps back and forth in chronology are so abrupt that for me it was never clear when several key plot points occurred. Does, for instance, a key tryst between Tashi and Patrick occur before or after she marries Art and bears his child? I honestly don’t know.

I can only tell you that Tashi’s behavior in the film is to me maddeningly unappealing. From the first, she’s using herself as a lure, promising her body to whichever of the two men wins an upcoming tournament. We’re supposed to see her as smart and scrappy, using tennis (as well as tennis players) to get what she wants out of life. Personally, although I couldn’t overlook Zendaya’s definite it-girl quality, I could find nothing very attractive in her machinations. Does she ever feel a genuine emotional connection with either of the two men she keeps in thrall throughout the film? I suspect not . . . so who are we rooting for?

The film ends, predictably, with Tashi’s two lovers battling it out on center court in the finals of a tennis tournament that will determine their careers but also their romantic lives. I won’t tell you who wins, partly because the filmmaker chooses to go for ambiguity, in the service of a finale that is more symbolic than particularly meaningful. It made me think back to a much early moment in Challengers, wherein a teenage Tashi pays a visit to the room shared by the two brand-new junior champions. Both clearly have the hots for her; both badly want to get physical with this tantalizing young woman. First she makes out with Art, and then with Patrick. Suddenly they’re all three wildly kissing. Then she silently backs out of the tryst, leaving two fellows smooching one another. Which, I suspect, is Guadagnino’s real focus in this film: the mutual attraction/repulsion of two male contenders. I don’t think Guadagnino likes women very much. And this film is his way of using a woman as a catalyst to show us his fascination with male-on-male carnal desire.

April 1, 2025

The Play’s the Thing: "Arsenic and Old Lace"

Once upon a time, hit movies got their start as Broadway plays. This was long true of blockbuster musicals, of course: think of the stage-to-screen metamorphosis of (for example) Oklahoma!, My Fair Lady, The Sound of Music, and Fiddler on the Roof. (Today, though musical theatre is a much harder sell than it once was, the current box-office success of the screen’s Wicked reminds us how a beloved stage play can translate into a motion picture bonanza.) But stage comedies without musical underpinnings have also been the source of screen success. Think back to 1936, and the Kaufman and Hart screwball stage hit, You Can’t Take It With You, about a family of lovable eccentrics whose daughter falls in love with the son of a stodgy banker. Two years later, the play was filmed with an all-star cast led by Jean Arthur, James Stewart, and Lionel Barrymore, winning Oscars for Best Picture and for Frank Capra’s direction.

The awards racked up by You Can’t Take It With You may have been somewhat unique (it’s rare for light comedies to take home top prizes), but there was a time when many a Broadway comedy enjoyed additional kudos for its screen iteration. Clearly loads of people who lived far from Broadway were eager to see shows they’d only heard about, especially if their favorite Hollywood stars appeared in the movie version. Here’s one example: a little farce called The Solid Gold Cadillac, a big Broadway hit of the 1954-55 season, was filmed in 1956. The little old lady of the stage version—someone who upends the business world with her unexpected financial savvy—became in the film the much-younger, much-cuter Judy Holliday, who won critical praise and a Golden Globe nomination.

Which leads me to mention that the little-old-lady star of the original stage version of The Solid Gold Cadillac was Josephine Hull, who was almost 80 when she created the role. Though she lost that part to the thirty-something Holliday, she did appear on screen in several classic stage-to-screen transfers, including Harvey (that’s the one with the invisible rabbit) and Arsenic and Old Lace. For the latter, released on screen in 1944, Frank Capra was again involved. This time the laughs came from a macabre set-up involving a Brooklyn theatre critic whose two sweet elderly aunts have a surprising habit of bumping off lonely old men with glasses of elderberry wine, delicately laced with arsenic, strychnine, and cyanide.

In the film version, Mortimer Brewster (a newlywed after a lifetime of disparaging marriage) is played by none other than Cary Grant. I’ve enjoyed Grant’s appearances in many film comedies (from Bringing Up Baby to Charade), but this may be his most physical role of all. His job is chiefly to react with astonishment to all the zany, grisly doings occurring around him, and Grant is definitely up to the challenge: watching him drop his jaw, bug out his eyes, and do elaborate double-takes is a masterclass in comedic acting. But there are lots of other talented farceurs involved. Chief among them are Jack Carson as a cop with dramatic ambitions, Edward Everett Horton as the proprietor of a lunatic asylum, Jean Adair as Josephine Hull’s lovably addled sister, and the inimitable Peter Lorre as a surgeon with a serious drinking problem. The stage version had featured Boris Karloff as Mortimer’s disfigured (and very scary) brother. As the biggest name in the cast (as well as the play’s chief investor), Karloff couldn’t leave the play to perform in the film version, so Raymond Massey (in Frankenstein-adjacent Karloff makeup) does the honors.

The Play’s the Thing: Arsenic and Old Lace

Once upon a time, hit movies got their start as Broadway plays. This was long true of blockbuster musicals, of course: think of the stage-to-screen metamorphosis of (for example) Oklahoma!, My Fair Lady, The Sound of Music, and Fiddler on the Roof. (Today, though musical theatre is a much harder sell than it once was, the current box-office success of the screen’s Wicked reminds us how a beloved stage play can translate into a motion picture bonanza.) But stage comedies without musical underpinnings have also been the source of screen success. Think back to 1936, and the Kaufman and Hart screwball stage hit, You Can’t Take It With You, about a family of lovable eccentrics whose daughter falls in love with the son of a stodgy banker. Two years later, the play was filmed with an all-star cast led by Jean Arthur, James Stewart, and Lionel Barrymore, winning Oscars for Best Picture and for Frank Capra’s direction.

The awards racked up by You Can’t Take It With You may have been somewhat unique (it’s rare for light comedies to take home top prizes), but there was a time when many a Broadway comedy enjoyed additional kudos for its screen iteration. Clearly loads of people who lived far from Broadway were eager to see shows they’d only heard about, especially if their favorite Hollywood stars appeared in the movie version. Here’s one example: a little farce called The Solid Gold Cadillac, a big Broadway hit of the 1954-55 season, was filmed in 1956. The little old lady of the stage version—someone who upends the business world with her unexpected financial savvy—became in the film the much-younger, much-cuter Judy Holliday, who won critical praise and a Golden Globe nomination.

Which leads me to mention that the little-old-lady star of the original stage version of The Solid Gold Cadillac was Josephine Hull, who was almost 80 when she created the role. Though she lost that part to the thirty-something Holliday, she did appear on screen in several classic stage-to-screen transfers, including Harvey (that’s the one with the invisible rabbit) and Arsenic and Old Lace. For the latter, released on screen in 1944, Frank Capra was again involved. This time the laughs came from a macabre set-up involving a Brooklyn theatre critic whose two sweet elderly aunts have a surprising habit of bumping off lonely old men with glasses of elderberry wine, delicately laced with arsenic, strychnine, and cyanide. In the film version, Mortimer Brewster (a newlywed after a lifetime of disparaging marriage) is played by none other than Cary Grant. I’ve enjoyed Grant’s appearances in many film comedies (from Bringing Up Baby to Charade), but this may be his most physical role of all. His job is chiefly to react with astonishment to all the zany, grisly doings occurring around him, and Grant is definitely up to the challenge: watching him drop his jaw, bug out his eyes, and do elaborate double-takes is a masterclass in comedic acting. But there are lots of other talented farceurs involved. Chief among them are Jack Carson as a cop with dramatic ambitions, Edward Everett Horton as the proprietor of a lunatic asylum, Jean Adair as Josephine Hull’s lovably addled sister, and the inimitable Peter Lorre as a surgeon with a serious drinking problem. The stage version had featured Boris Karloff as Mortimer’s disfigured (and very scary) brother. As the biggest name in the cast (as well as the play’s chief investor), Karloff couldn’t leave the play to perform in the film version, so Raymond Massey (in Frankenstein-adjacent Karloff makeup) does the honors.

March 27, 2025

Recalling Stardust Memories

The recent passing of Marshall Brickman made me curious about his collaborations with Woody Allen. The two shared writing credit on such Allen hits as Sleeper, Manhattan, and particularly Annie Hall, which earned the duo an Oscar for Best Original Screenplay in 1977. At my local library I checked out a volume of Woody Allen screenplays from perhaps his most fertile period, the late 1970s.. Two of them—Annie Hall and Manhattan—were written with Brickman’s participation. The other two—Interiors and Stardust Memories—were solo outings by Allen. My not-very-scientific conclusion: when collaborating with Brickman, Woody Allen was more grounded in the here-and-now. I think Brickman brought the hypertalented Allen down to earth, negotiating with him an effective balance of comedy and genuine emotion.

Of the two screenplays Woody Allen wrote solo, Interiors is considered by most critics and audiences a flop, a lugubrious story of failed romances, lacking the impish humor that has always been Allen’s trademark. Then there’s Stardust Memories (1980), something of a hodgepodge, but a fascinating one. This is Allen (or at least an Allen-like character) confronting his own celebrity as both director and performer, dealing with the fact that both studio execs and film fans strongly prefer his “early funny ones” to his own ambitious goal of capturing human suffering through cinema.

In Stardust Memories, Allen is Sandy Bates, a well-known comic filmmaker who apparently aspires to be the next Fellini. He’s got a new movie in the can, but the studio honchos are not thrilled by an ending involving two old-fashioned passenger trains. One train car contains Sandy’s character and a clutch of riders who are clearly living lives of quiet desperation. The other, which Sandy stares at longingly through the train window, transports jolly revelers wearing furs and holding up awards statuettes for all to see. They’re having a great time . . . . but suddenly this lively crowd is off the train and picking its way through a garbage heap. Talk about blatant symbolism!

At a Florida hotel where Sandy’s the honored guest for a tribute weekend, he’s constantly surrounded by a swarm of fans, most of them slightly grotesque. Some want to kiss him; some want to kill him. Everyone wants something: a souvenir photo; an opportunity; a contribution to a worthy cause; a roll in the hay. As he struggles to avoid their clutches, as well as the pedantic clichés of some film-scholar types in attendance, he’s simultaneously wrestling (as Woody Allen heroes generally are) with romantic angst. There’s the gorgeous but emotionally fragile Dorrie (Charlotte Rampling), as well as the pretty mother of two cute French-speaking tykes (Marie-Christine Barrault) and a young violinist who considers herself bad news (Jessica Harper). Then Sandy is confronted by a clutch of visitors from Outer Space (they too prefer “the early funny ones”) and is faced with an unexpected life-or-death moment (don’t ask).

In watching Stardust Memories (which, by the way, is scored with some wonderful Dixieland tunes, including a Louis Armstrong rendition of “Stardust”), I couldn’t help thinking about a movie classic, Sullivan’s Travels This 1941 film, written and directed by Preston Sturges, concerns a successful director of Hollywood comedies who yearns to work on a serious project about the plight of the downtrodden. Having gone on the road to soak up true Americana, he ultimately comes to realize the value of comedy in soothing people’s harsh daily lives. Ia this what Woody Allen is trying to convey to us in Stardust Memories? Honestly, it’s hard to say. But he’s certainly given us a lot to chew on.

March 24, 2025

Art, Angst, and Almodóvar

I’ve long been fascinated by the brilliant Spanish filmmaker, Pedro Almodóvar. And I’m hardly alone. The new Academy Museum has, until recently, devoted one large gallery to provocative (and hardly child-friendly) clips from Almodóvar’s best work. And on April 28, he’ll be honored by Film at Lincoln Center with its 50th Chaplin Award. But I can’t pretend I know all there is to know about the man behind such international hits as Woman on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown, All About My Mother, and Talk to Her. That’s why I dove into a slim but tightly packed new book from Columbia University Press, titled The Passion of Pedro Almodóvar: A Self-Portrait in Seven Films.

Author James Miller is not your usual film scholar. A professor of politics and liberal studies at the New School for Social Research, he has turned a COVID-era movie-watching project into a serious exploration of Almodóvar’s entire life and career. Clearly a methodical thinker, he lays out at the beginning of his book his conviction—following a close viewing of every Almodóvar film—that his subject “was essentially a man of the sixties, forged in Spain’s belated version of that decade’s global counterculture and seriously pursuing his own quest for philosophical insight and personal liberation.” He sees in Almodóvar’s films a passion for self-examination, one deeply rooted in European philosophical tradition. Miller’s preface ends with the assertion that “Almodóvar has long been fascinated by the blurry line between fiction and reality, between cultural memory and personal memory, between autofiction and autobiography.” The author announces here his plan to analyze the master’s creative process “in a way that allows Almodóvar to emerge both as a real person as well as a fictional character represented in multiple alter egos in various films.”

To this end, Miller selects seven of Almodóvar’s films to discuss in depth. Each reflects, though hardly in a conventional way, some aspect of Almodóvar’s private life. Instead of arranging the movies chronologically in terms of their release dates, Miller chooses to match them with key periods of Almodóvar’s own personal chronology. That’s why he begins, following a biographical sketch of the artist’s life trajectory, with the 2006 release Volver, viewing it as Almodóvar’s return to the rural La Mancha of his boyhood and to the hard-scrabble working class section of Madrid in which he spent his youth.

The next film he discusses is 2004’s Bad Education (its original Spanish title, La mala educación can also mean “bad manners”). This often startling work contains a cinematic version of a key moment in Almodóvar’s own childhood. As a boy with a keen mind and an angelic singing voice, he was a prized pupil at a boarding school run by Catholic priests. He suffered sexual abuse at the hands of one of them. Bad Education contains this horrendous moment, but also jumps ahead in time to a film being made about the incident and its aftermath, with the victim himself apparently playing one of the lead characters. In the unique way with which, in Miller’s terms, Almodóvar “nests” various story elements inside one another, Bad Education then turns into a kind of film noir, with eerie mistaken identities pointing toward a latter-day crime that becomes downright Ripley-esque.

The later films on Miller’s list explore the period of Almodóvar’s young manhood in the gaudy so-called La Movida movement of the 1960s as well as (in 2019’s Pain and Glory) the mature filmmaker’s acknowledgment of his own homosexuality. As always, the latter film’s director character is and is not the master himself. But he’s certainly worth our attention.

March 21, 2025

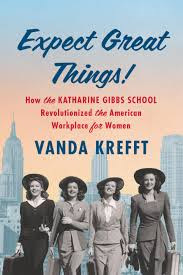

Achieving the Best of Everything: The Katharine Gibbs School

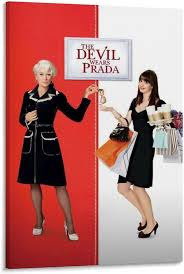

It’s a long-time movie staple: an attractive young lady comes to the big city (generally Manhattan) with stars in her eyes. She gets a low-level job and struggles to move forward, while at the same time fending off the advances of cads and hoping to find True Love. It’s a plotline exemplified by the all-star 1959 film, The Best of Everything (based on a steamy Rona Jaffe best-seller). But the same basic story thread shows up elsewhere too, as in 2006’s well-loved The Devil Wears Prada, in which—for a change—the all-controlling boss is a woman. In most films of this sort, the ending for the central character is basically (despite some missteps along the way) happily ever after.

The notion of smart, well-trained young women finding their place in the world of work was central to a once-powerful American institution, the Katharine Gibbs School. Far more than a secretarial college, Gibbs (which in its heyday had several east coast campuses) was a place where bright young women could pave their way to future success. While working hard to master demanding courses in typing and shorthand, Gibbs students also were schooled in literature, psychology, finance, and other fields, all the better to make them ideal employees. Some laughed at the dress code: when in public, Gibbs “girls” were required to be elegantly turned out, in neat suits, face-framing hats, and white gloves. But Gibbs alumna were models of professionalism, with the skills and the confidence to move beyond entry-level positions and attain the highest ranks in fields like government, banking, publishing, and even aviation. Several, in fact, made their mark in the entertainment industry, not only as actors (Loretta Swit of M*A*S*H fame was a graduate) but also as behind-the-scenes executives, writers, and publicists

I know all of this because of a fascinating new book by a colleague, Vanda Krefft. Her Expect Great Things!: How the Katharine Gibbs School Revolutionized the American Workplace for Women traces the institution from its founding through the war years, exploring the lives of highly-successful Gibbs graduates, many of whom managed to combine career success with happy family lives. She parses the triumphs of the Fifties, then reveals how, in the turbulent late Sixties, the whole Gibbs philosophy fell by the wayside as second-wave feminism and the general iconoclasm of the era made the old rules seem out-moded.

Though I was captivated by many of women featured in Krefft’s well-researched and nicely written pages, what sticks in my mind is the story of the school’s founder. She was born in 1863 in Galena, Illinois, one of eight children of a businessman who, despite immigrant roots, worked his way into a position of wealth and power in his local community. In an age when upper-class women were meant to be merely decorative, Katharine lived comfortably, but never went beyond a high school education. Her father’s sudden death changed everything; since he left no will, her older brothers took charge, and managed to squander the estate.. Ultimately she married and had two children, but, when she was forty-six, her well-meaning husband died in a freak boating accident. Again there was no will, and she had to fight even to be the decision-maker for her own sons. Left with nothing but mouths to feed, she decided to start a school teaching other woman how to think for themselves, and how—in times of crisis—not to be beholden to men for their livelihood. Somehow it worked. I can well imagine Gibbs’ story on the big screen, maybe with a plucky Claudette Colbert or Joan Crawford in the leading role.

Beverly in Movieland

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers