Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 3

June 26, 2025

Tina Fey in All Seasons

I’m surely not alone in considering Tina Fey a nationaltreasure. She has oodles of talent as a performer, and is a welcome MC attelevised events. But I want to focus here on her brilliance as a writer,someone who can look at facets of our culture run amok and synthesize them intocomedy gold.

Fey has been involved with television since her SaturdayNight Live days (basically 1997-2006, though who can forget her return asSarah Palin before the 2008 election?) In 2006 she created and starred in 30Rock, an hilarious satire of a TV network, and she was also responsible forUnbreakable Kimmy Schmidt, which I found weird and funny. As ascreenwriter, she made a brilliant debut with the 2004 teen comedy, MeanGirls. Who but Tina Fey would be smart enough to read a self-help bookabout adolescent bad behavior, sociologist Rosalind Wiseman’s Queen Bees andWannabes, and fashion it into a hit movie?

It helped a great deal that the film was populated by risingyoung stars, including Lindsay Lohan, Rachel McAdams, Lacey Chabert, and AmandaSeyfried, along with Fey herself (in a teacher role) and best bud Amy Poehler,playing a particularly indulgent mom. This now-classic satire of high school girl-cliqueshas ultimately become a part of the American vocabulary, labeling self-improvedand self-satisfied young women as “The Plastics” and introducing the concept ofa “burn book” full of deliciously malicious gossip. (Clearly this reference iswhat led tech journalist Kara Swisher to publish in 2004 her Burn Book: ATech Love Story. I’m also amused that the main non-conformist girl in thefilm, the one who aims to bring down The Plastics for reasons of her own, is dubbedJanis Ian, immortalizing the young singer/songwriter who had expressed her ownteen angst through major pop hits like “At Seventeen.”)

So potent has Mean Girls been that it was reincarnated,with Fey’s help, as a 2018 Broadway musical and a subsequent 2024 filmadaptation. But Fey has not been idle since. It intrigues me that her mostrecent project is a mini-series which has just been renewed for its second seasonon Netflix. Again she chose her source carefully: a 1981 film written, directedby, and starring the wonderful Alan Alda. Alda’s The Four Seasons, which(natch!) features a lot of Vivaldi on the soundtrack, chronicles three well-heeledmarried couples who are close friends and always vacation together. Over thecourse of a particularly eventual year, one husband strays in dramatic fashion,and the others begin to question their lives and their values. The cast isfirst-rate (Carol Burnett plays Alda’s hyper-efficient wife, and Len Cariou,Sandy Dennis, Jack Weston, and Rita Moreno are the others in the friend-group).It was nice to see, at the beginning of the Netflix mini-series, the noweighty-nine-year-old Alda in a gracious cameo role.

The first season of Fey’s Four Seasons miniseriesessentially expands on the basic concept of Alda’s film, showing mature adults—longsettled into marriages and careers—suddenly re-thinking their life-choices. It’sinteresting to see Fey, who essentially plays the Carol Burnett role, wrestlingwith being a middle-aged person. We’re so used to her focusing in her projects onteenagers and on career gals: now she’s portraying a wife and the mom of acollege-age daughter, someone who has made good choices but is starting towonder what it all means. At 55, as a wife and a mother of two, Fey is clearly beginningto contemplate the full trajectory of a mature life. And we get to come alongfor the ride.

June 24, 2025

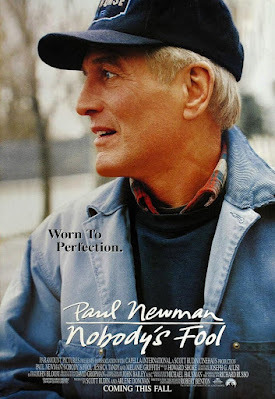

Older Doesn’t Always Mean Wiser: “Nobody’s Fool”

Why’d I watch a 1994 character piece called Nobody’s Fool?Partly it had to do with the death in May of writer/director Robert Benton,whose down-to-earth work I’d long admired. As a complete unknown, he co-wrote(with David Newman) Bonnie and Clyde, one of the most remarkable filmsof the remarkable film year 1967. Over a decade later he both wrote anddirected Kramer vs. Kramer, winning himself two Oscars. And there wasanother Oscar in 1984, honoring his original script for Places in the Heart,a film based—I’m told—on his own Texas family. He directed that onetoo.

Watching Nobody Fool was my salute to Benton’s talentfor making the everyday seem special and unique. It was also my tribute toco-star Jessica Tandy, for whom this was a final film. (The original BlancheDuBois died at age 85, just before the film’s release.) Many others inthe film’s cast are also no longer with us: it’s particularly poignant to seePhilip Seymour Hoffman in the small but goofy role of a small town cop who’s alittle too quick on the trigger. But of course the biggest loss has been thatof star Paul Newman, who—then just shy of 70 years of age—was nominated yetagain for a Best Actor Oscar for this role. (He lost to Tom Hanks in ForrestGump, but at this late point in his career Newman had already finallysnagged a statuette for The Color of Money.) He would be nominated oncemore for 2002’s Road to Perdition, voiced a role in Disney’s Cars in2006, and passed from the scene in 2008, at age 83.

Nobody’s Fool is poignant, but also quite funny. (Atleast some of the credit should go to novelist Richard Russo, who wrote thenovel on which the film is based.) Set in the dead of winter in an upstate NewYork hamlet where everybody knows everybody’s business, it focuses on Donald“Sully” Sullivan, a sometimes-construction worker with a bum knee, anappreciation for poker, and a boyish enjoyment of playing tricks on his boss(Bruce Willis). He may seem happy-go-lucky, but there are dark memories of adrunken father and of his own greatest misstep: walking out on a wife and youngson many years before. Though he only moved across town, Sully and his son havenever re-connected. But the son is back now, with kids and problems of his own,and Sully finds himself in the odd position of needing to act like a grown-up.It’s a layered and thoroughly fascinating performance.

Part of what makes the film feel so lived-in is the castingof veteran actors who really help the fictional North Bath, New York feel likea community full of lovable eccentrics. There is, for instance, the ratherinept lawyer (Gene Saks) who puts up his artificial leg as his stake in a pokergame. Bruce Willis, who reportedly took a major pay cut for the chance to actwith Newman, is memorable as the construction boss (and feckless womanizer) whomakes Sully’s life miserable but owns a really classy red snow-blower thatbecomes a running joke. As Willis’s neglected wife, Melanie Griffith is herappealing self.

What’s really striking about Newman’s character is that—forall his reputation as a ne’er-do-well—he turns out to be one of the kindestsouls in town. It’s his kindness that Jessica Tandy sees in him when sherefuses to stop being his landlady, despite her own son’s bluster. Yes, he’s anuisance, but we sure need more of his ilk.

June 20, 2025

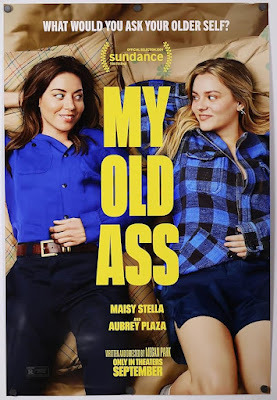

Scratching My Old Ass

My Old Ass, a dramedy that popped up at the end of 2024, seems atfirst glance a raunchy teen flick, full of lots of giggling, girl-on-girl sex,and gorgeous vistas of the Canadian countryside. It’s only later that theviewer discovers the film’s tender heart. And realizes that writer/directorMegan Park, a Canadian multi-talent who has much more on her mind than teenagevulgarity, is headed for a bright future.

It's the end of summer, avery poignant time if you’re about to leave home for college in the big bad city. Elliott and her gal pals (why thistrend of giving leading ladies masculine character names?) are camping on theshore of a local lake, celebrating Elliott’s eighteenth birthday and pondering what the future will hold. There’s aceremonial ingestion of magic mushrooms, and Elliott wakes up in her tent to discoveran unexpected visitor, a thirty-something version of herself (Aubrey Plaza).

Elliott is skeptical, ofcourse, but is finally persuaded that this older pal is a future incarnation ofherself, sent to guide her on her pathway toward adulthood. It all soundshelpful . . . until Older Elliott sternly warns her not to have anything to dowith a guy named Chad. No prob: she doesn’t know anyone named Chad. But then .. . a nice-looking young man comes paddling up, and she’s trying hard not to besmitten.

The film’s central sectionhas Elliott desperately trying to avoid Chad, for reasons that she can’texplain and her “old ass” (who’s just a phone call away) refuses to clarify. Chadis kind, smart, and good-looking: what’s not to like? It’s not until late inthe movie that Elliott decides—despite all the warnings—that Chad is just toogood to be removed from her life. It’s then that Older Elliott finally admits howand why a relationship with Chad will upend her life . . . and belatedly agrees that, despite it all, heis worth the pain that will inevitably arise.

Far be it from me to spillall the script’s secrets. Let’s just say here that this wacky teen comedyevolves into a serious exploration of the heartache that is all a part ofgrowing up and moving out into the world. (Aside from the whole Chad business,Elliott needs to come to terms with her parents, who’re suddenly planning tosell the cranberry farm on which she wasraised, And she needs to make peace with her younger brothers, whose goals inlife seem hugely different from her own.)

The coming of age dramedy hasalways been popular with movie-going audiences, dating back to Mickey Rooney inthe Andy Hardy films. In my own generation, The Graduate (1967)was the movie that spelled out the joys and pitfalls of impending adulthood.The year 1978 saw an exuberant high school musical based on the stage hit, Grease.The previous year had brought us the star of Grease, John Travolta,girding up to move beyond Brooklyn in Saturday Night Fever. The Eightieswere, of course, the era of John Hughes, who—in films like Sixteen Candles,The Breakfast Club, and Pretty in Pink—explored the pain andpleasure of high school.

The eighteen-year-olds of My Old Ass are hardly as innocent as the Andy Hardy gang or even JohnHughes’ youthful ensembles. Sex and drugs are definitely a part of their lives.Still, they remain good kids, tentatively checking out the world they’re goingto inherit. I defy you not to be touched..

June 17, 2025

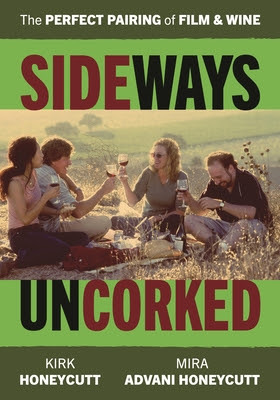

“Sideways”: Grapes, Nuts, and Flakes

Quaffed any good pinot noir lately?The grape got new respect in 2004 via Alexander Payne’s Sideways, a boxoffice hit that was also a critical darling. (It was nominated for five Oscars,including Best Picture, and won for the adaptation of Rex Pickett’s comic novelby Payne and co-author Jim Taylor.) I’ve long used it in my UCLA Extensionadvanced screenwriting courses as one way to approach various aspects of thescreenwriter’s craft. Sideways provided a major boost to the actingcareers of Paul Giamatti and his castmates, as well as a shot in the arm totourism in California’s Santa Ynez Valley. It also upended the wine industry:after the advent of Sideways, merlot was considered by many to be a winegrape non grata.

In 2024, Applause Booksreleased Sideways Uncorked, described on its cover as “the perfectpairing of film and wine.” There’s no question that the authors know whereofthey speak. Kirk Honeycutt was for twenty years a writer and then the chieffilm critic of The Hollywood Reporter. So he knows the film world insideand out. His in-depth understanding of independent films like Sideways wasenhanced by his experience with low-budget maven Roger Corman on Final Judgement, a 1992priest-and-stripper quickie for which Kirk wrote the original screenplay. (AsRoger’s story editor I worked with Kirk on the project. I best recall a little momentin which the accused killer tries to get away from potential danger by climbingaboard a city bus. Roger refused to accept this quirky choice, reasoning that abadass required a motorcycle or something cooler than public transit. Thus myboss firmly rejected what I had found original and characteristic.)

In this book, it’s Kirk’s jobto explain how Sideways came to be, how it was written, financed, cast,shot, and distributed. Part of his focusis on the implications of Sideways being an indie film: by not allowinga studio with deep pockets to dictate key artistic choices (like the dreamcasting of George Clooney and Brad Pitt in the leading roles instead of theless glamorous Paul Giamatti and Thomas Haden Church), Payne preserved hisvision of this film as featuring two ordinary down-on-their-luck guys.

Kirk’s insider stories aboutthe making of Sideways, corroborated by the film’s cast and crew, areaugmented by the contributions of his wife, Mira Advani Honeycutt. A longtimewine journalist, she puts her expertise to work in explaining the realities ofthe wine industry, especially as this applies to the Santa Ynez Valley. Shebegins by focusing in on the all-important physical properties of the area,what the French call “terroir.” Theseare the environmental factors—relating to weather, soil quality, and thelike—that determine which grapes can be most successfully planted in a givenplot of land. Santa Barbara County’s Santa Ynez Valley offers vastly differentclimate conditions from Northern California’s famous grape-growing counties,and she traces the history of pinot noir cultivation in the region, showing indetail how this notoriously finicky grape (see Giamatti’s now-famous speechabout the special needs of pinot) thrives in its soil. For wine lovers, shealso advises on the best wineries for pinot noir in California, Oregon, andelsewhere. Nor does she neglect merlot, which is scorned by Giamatti’scharacter in the film, but certainly is worthy of having its own enthusiasts.It’s amusing to note that the book is dedicated “to Cinephiles, Pinotphiles,and Merlot Mavericks.”

Want to know how thereal-life owner of a Solvang restaurant made a fortune off the success of Sideways?This book’s for you.

June 13, 2025

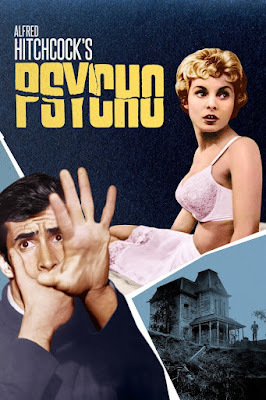

Going “Psycho”

The other evening, in theline of duty, I went back in time and watched Alfred Hitchcock’s 1960masterwork, Psycho. Ironically, I never saw it in a theatre back in theday. (I was a young teenager at the time, and not especially keen on horror.)Needless to say, I’d heard all the brouhaha, and was aware that Janet Leigh’scharacter didn’t fare well during her overnight stay at the Bates Motel. Butthe intricacies of her killer’s identity were beyond me—until I took a long busride with a gaggle of other girls, and one filled me in on the entire plot.

I’ve since seen the film, ofcourse, though it’s been a while. But because I was asked to comment on a newbiography about a Hollywood regular (Christopher McKittrick’s Vera Miles:The Hitchcock Blonde Who Got Away), it seemed appropriate to check outMiles’ appearances in films by legends like John Ford (The Searchers)and Alfred Hitchcock. Miles was, I learned, slated to become Hitchcock’s nextleading lady, once Grace Kelly decamped for Monaco. After portraying HenryFonda’s long-suffering wife in The Wrong Man, Miles was his originalchoice to play the fascinating female lead in Vertigo (1958), untilscheduling problems got in the way. Still, she was featured by Hitchcock in thedrama that kicked off his well-loved TV series. And for Psycho sheplayed the important (though not especially interesting) role of Janet Leigh’ssister, searching for the missing MarionCrane and letting out an impressive scream when she learns the truth about thespooky old lady in the big Victorian house.

Psycho may be today one of Hitchcock’s best remembered films,but it’s far from typical of his oeuvre. Yes, it features a pretty blonde womanin dangerous circumstances, but Janet Leigh’s role in Psycho is farremoved from those played by such Hitchcock blondes as Madeleine Carroll, EvaMarie Saint, Grace Kelly and Tippi Hedren. Whereas the usual Hitchcock heroineis elegantly attired, Leigh’s Marion Crane is most familiarly depicted wearinga bra and slip. She’s attractive, but she’s no mysterious glamour girl caughtup in international intrigue. The criminal act of which she’s guilty is thesordid little matter of stealing a wad of cash from her employer so thatperhaps she can finance a marriage to her not-so-willing boyfriend (John Gavin,a future US ambassador to Mexico).

Hitchcock’s decision to castJanet Leigh, a rising star with a well-publicized Hollywood marriage (to TonyCurtis) as Marion Crane meant that the bulk of his budget went toward hersalary. The result was that other aspects of Psycho were necessarilysimplified. It was shot, mostly by Hitchcock’s TV crew, in austere black &white, in contrast to such glossy full-color Hitchcock productions as 1958’s Vertigoand 1959’s North by Northwest. But in fact this austerity seems tosuit the simple but macabre story.

One thing I never realizeduntil I read the Vera Miles bio is that Hollywood, in its wisdom, eventuallydecided to sequelize Psycho. Hitchcock was dead and gone in 1983 whenUniversal Pictures paid Richard Franklin to direct Psycho II, set 22years after the original story. Marion Crane played no part, of course, butAnthony Perkins signed on to again play Norman Bates, newly released from amental institution. And Vera Miles signed on too, to portray the still-grievingsister who thirsts for revenge. Naturally there are mysterious and macabredoings galore . . . and three years later, Perkins himself directed PsychoIII, described as a psychological slasher film. Happily, I missed thesecinematic gems.

June 10, 2025

Peru Comes to the Vatican . . . and Hollywood

Understandably, there’s beenmuch press coverage of Leo XIV, the newly anointed first American-born pope.Though a native of Chicago, Leo (born Robert Francis Prevost) has close linkwith the nation of Peru, where—after years of missionary work—he took onPeruvian citizenship. His strong emotional ties to that picturesque SouthAmerican nation reminded me of Mario Vargas Llosa, the Peruvian Nobel laureatewho died this past April at age 89.

Vargas Llosa was a man ofletters who in 1990 nearly became Peru’s president. (He was defeated in alandslide by Alberto Fujimori, who quickly claimed dictatorial powers and wasrun out of the country 10 years later.) A prolific writer of both fiction andnon-fiction, Vargas Llosa began his literary career circa 1960. Though I’veread his charming early work, known in English as Aunt Julia and theScriptwriter, I by no means pretend to be an expert on his entire oeuvre.Still, for a time I worked closely with his younger cousin, Luis Llosa Urquidi,familiarly known as Lucho.

When I was Roger Corman’sstory editor at Concorde-New Horizons in the late 1980s, we shot manylow-budget features in Argentina, taking advantage of the exotic locales andcheap labor costs that the current U.S. regime is striving to combat with tariffthreats. At one point Roger was flying to Buenos Aires to check on a troubledproduction, but bad weather forced the plane to land in Lima, Peru.Screenwriter Fred Bailey told me what happened next: Roger “got off the plane,took a taxi into town, opened up the yellow pages, and got somebody to findmotion picture production listings. Made a few calls asking who was the bestfilmmaker in Lima . . . they all said, ‘Luis Llosa.’ Called him up, made adeal, and was back on the airplane to Argentina within a couple of hours.”

Through Lucho, Rogerdiscovered a wealth of Peruvian locations: crumbling colonial cities, toweringmountain ranges, a long seacoast, lots of jungle. There we shot everything fromecological thrillers (Fire on the Amazon) to a submarine drama (FullFathom Five) to a rather fascinating Bonnie-and-Clyde-in-the Future project(Crime Zone). More than once we used the jungles of Peru to stand in forVietnam in would-be war epics. What made shooting in Peru particularly excitingwas the fact that this was the era of the Shining Path, an armed guerrillagroup aiming to launch a People’s War against established government entities. OneCorman production was actually briefly put on hold when the Shining Path tookover a location. I’m certainly not complaining about the fact that I, as storyeditor, remained safe in my office in Brentwood, California.

Of course Lucho, despite histhriving cinematic career in Peru, aspired to make American movies withprospects beyond those of the low-budget Corman world. His biggest success wasa 1997 creature-feature called Anaconda, shot in South America with abig-name cast that included Jennifer Lopez, Ice Cube, Jon Voigt, and OwenWilson. This snake-infested horror movie grossed $136.8 million worldwide andquickly became a popular franchise. It earned money but not respect, ending upnominated for six Razzie Awards (including Worst Picture, Worst Director, WorstActor, and Worst Screenplay), all of which it lost to Kevin Costner’s ThePostman. Still, today it’s considered a cult classic.

Another successful member ofthe Llosa clan is writer/director Claudia Llosa Bueno, niece of both Mario andLucho. Her second feature, The Milkof Sorrow, explores the folk beliefs of indigenous Peruvians. In 2010 itwas nominated for the Best Foreign Film Oscar.

June 5, 2025

Water, Water, Everywhere: Life of Pi

Life of Pi is many things to many people. It can mean YannMartel’s deeply philosophical novel, which after numerous rejections came outin 2001, immediately attracting readers and winning major prizes. It can meanthe 2012 film version, which nabbed eleven Oscar nominations and won fourstatuettes, one of them for Ang Lee’s inspired direction. It can mean the stageadaptation I saw recently in Los Angeles, following residences in London andNew York.

The stage and film versionsof course have to meet the challenge of depicting a boy on a small boat in themiddle of the Pacific Ocean. And, oh yes, his companion throughout this wateryjourney is a large and very hungry-looking Bengal tiger. The production I sawat L.A.’s Ahmanson Theatre was heavily reliant on what we might call stagemagic. The show effectively used both light and sound to suggest the brinydeep. And that tiger? Here the production team turned to an artform that has earnedrespect on western stages only in the last fifty years or so: puppetry. When wethink of puppets, it’s easy to focus on child’s play: on Punch and Judy or ontheir rather more sophisticated cousins, the Muppets. Other cultures, though,have made deeply serious and deeply adult use of puppets in their theatres andeven in their religious rituals. (See the shadow puppets of Indonesia who actout sacred myths on behalf of the whole community.) I’m personally a big fan ofJapan’s bunraku, in which large doll-like puppets perform traditionalromantic stories that can be poignant, even genuinely tragic.

I credit Julie Taymor withdiscovering that puppets belong on the Broadway stage when in 1997 she took onthe challenge of directing The Lion King, a live-action version of thebeloved Disney film. Ten years later, a best-selling novel called WarHorse was dramatized in London, featuring life-size horse puppetsmanipulated by several well-coordinated actors. In Life of Pi, twohighly-trained human performers slip under the skin of that tiger, and othersin the cast make a zebra, a hyena, an orangutan, and a large turtle come tolife before our eyes.

The movie version of Lifeof Pi poses different challenges. Movies by their nature need to look real;there’s not the willing suspension of disbelief that distinguishes an audienceresponse to a theatrical performance. Filming on water is hardly easy. Thatfact was acknowledged by my former boss, Roger Corman when he turned down a chance to make an earlyversion of Water World. (Kevin Costner’s 1995 take on this futuristicstory, in which rising sea levels have made dry land mostly disappeared, wasseriously weighed down by a huge production budget.) Still, these days it’s notimpossible for a well-trained movie crew to make a large tank on a studio lotlook like an entire ocean.

But the challenge of the cinematicLife of Pi was less the ocean than the animals. Here’s where modern CGIcame into its own: the film’s central critters are almost entirelycomputer-generated, and the young Indian actor playing Pi was never in contactwith a dangerous wild beast. (Needless to say, Suraj Sharma’s role was not aneasy one: he had to react to the moods and moves of creatures who were simplynot there.)

The Oscars won by Life ofPi are a testament to the film’s technical brilliance. In addition to AngLee’s directorial triumph, the film was honored for its remarkablecinematography and visual effects. To be honest, though, it’s not as riveting amovie as the eventual Best Picture winner, Argo.

June 3, 2025

Losing the Invaluable Frances Doel

It saddens me to report that Frances Doel is no longer withus. Frances, the right-hand woman of Roger Corman for many a decade, passedaway last week at age 83. Late in life she had moved from Hollywood to Lexington,Kentucky to be tended by family members who loved her dearly. Honestly, she wasdearly loved by everyone who knew her.

Roger Corman met Frances at Oxford, where she was completinga degree in literature. Always a shrewd judge of character, he concluded shewas smart enough and agreeable enough to make a good assistant. And so shewas—learning from scratch pretty much every job involving a movie set or aproduction office. Her obituary notes that she ghost-wrote the first draft ofmany a Corman classic, and named among her official writing credits 1974’s BigBad Mama, starring Angie Dickinson, William Shatner, and Tom Skerritt. I was there, and I’m happy to share how thisfirst Frances Doel screen credit came to be.

Starting work as Roger’s new assistant in 1973, Iimmediately gravitated toward the New World Pictures story department, whichwas Frances. Roger wanted a seriocomic rural crime thriller à la Bonnie and Clyde.Back then, he was obligated to use WGA writers, and it was a lot cheaper tohire a union writer for a re-write than for an original script. That’s why hegave Frances an entire weekend to crank out a workable first draft. Of courseshe came through with flying colors, devising a story about a poor but feistymother and her two nubile daughters who take up robbery in Depression-eraTexas. She slapped a fake name on the draft, and we hired a veteranscreenwriter to take over.

William Norton, a very nice guy, seemed to enjoy storymeetings with Frances and me. As we worked our way through characterizationsand plot points, Bill started wondering aloud about the author of the original draft. He went so far as to askif this “man” could come in and discuss some story questions he had. At whichpoint, Frances and I began to giggle. Eventually we couldn’t hide the fact thatFrances herself was the screenwriter in question. A true gentleman, Billinsisted that she share script credit with him. It was the start of her stringof Corman writing credits, which ultimately included such low-budget classicsas Crazy Mama and Sharktopus.

Did Frances get paid extra for her weekend labors? Shecouldn’t recall exactly, but suspected that BigBad Mama earned her about $100. Over the years, her earnings increased,netting her $5000 each for quickie creature-features like Dinocroc. But she never entirely earned Roger’s full respect. As shetold me in 2011, soon after her retirement, “Roger got very fed up with me,”because he didn’t feel she was writing fast enough. Ten script pages a dayseemed to him a reasonable amount, even though she was putting in this worksolely on evenings and weekends.

Frances stayed with Roger in various capacities for decades,earning the genuine praise of such celebrated Corman alumni as John Sayles andRon Howard. But the time came when she got a better offer, moving on to Disney,and then ultimately joining with Corman alum Jon Davison to produce hits like StarshipTroopers. Eventually she hit on hard times, and Roger—in a burst ofgenerosity—gave her my job as Concorde-New Horizons story editor. Ithurt, but I couldn’t blame Frances. She was too gracious and too special forthat.

And I could never have written my Roger Corman bio withouther.

May 30, 2025

Bruce Logan: On the Beach and On the Moon

I first met Bruce Logan whenhe was getting married. Well, sort of. Back in 1974 I was serving as productionsecretary on the Roger Corman gangster romp, Big Bad Mama, which starredthe odd triangle of Angie Dickinson, William Shatner, and Tom Skerritt. (Yes,there were some wild and crazy sex scenes.) Part of my job was to keep track ofcast and crew. So I knew it was a very big deal that Bruce Logan was ourdirector of photography. After all, he had been a young visual effects whiz,working directly with Stanley Kubrick and SFX master Douglas Trumbull on 2001:A Space Odyssey. A self-taught animator, he began work on 2001 in1965, at age 19, and stayed with theproject through the film’s release in 1968. That same year, he left his nativeEngland, coming to California to collaborate with Trumbull on Antonioni’sapocalyptic Zabriskie Point (1970).

Given his classy resumé, wewere all impressed that Bruce Logan was willing to work on low-budget RogerCorman fare. But there he was, fitting in nicely with our misfit crew. The lastday of our three-week Big Bad Mama shoot, we threw ourselves a wrapparty on the site of our final location, Malibu’s Paradise Cove. To add to thefun, we staged on the sand a mock wedding for Bruce and his girlfriend, whowere apparently planning to get hitched for real in the near future. A veteran actor,Royal Dano, had played a scoundrel of a minister in the film: he was persuadedto put on his clerical robes and conduct the ceremony with great theatricalflourish. If memory serves, most of the ad hoc wedding party ended up splashingin the waves. And a good time was had by all.

I didn’t think much aboutBruce over the years, until filmmaker friends invited me to a gathering atwhich he was being given a lifetime achievement award. This was around 2009,and his filmography had swelled to include providing visual and optical effectsfor the first Star Wars film (1977) and cinematography for the ambitioussci-fi epic, Tron (1982), in which a computer hacker is abducted into adigital world. I was then working on a book that took readers back to the filmyear 1967, and I had a hunch that Bruce would have some opinions about that erain which both he and I were youthful film enthusiasts. He graciously invited me to his PacificPalisades home for what turned out to be a long, fascinating chat. He was animposing figure: tall, with white hair and beard. His clothing wasconservative, except for a beaded necklace and that heavy silver skull braceleton his left wrist. Underneath it all, I suspect, Bruce Logan would forever be abit of a hippie, though he no longer had the long flowing locks of his 2001 days.

Our conversation waswide-ranging. Of course we discussed Kubrick’s prescience in making 2001,which features convincing-looking computer screens and read-outs decades beforedesktop computers actually existed. With the advent of the U.S. space program,new data was coming in about the lunar surface, at the very same time thatKubrick and company were deciding what their moon’s back side shouldlook like. They thought of altering their concept to match the science, thendecided that, frankly speaking, “the moon looks kind of boring.” Ultimately,they stuck by their own artistic vision, one that would prove inspiring tocountless Baby Boomers.

Bruce Logan died on April 10,2025. I wish we could have had another long, fruitful chat.

May 27, 2025

Shooting Day for Night

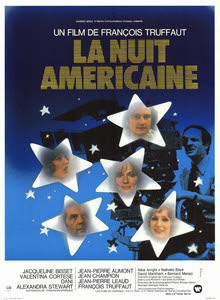

Day for Night, in commonmovie parlance, is the process of shooting film during daylight hours but usingfilters to convince the audience that the scene takes place afternightfall. Day for Night is alsothe English-language title of a 1973 film that was a labor of love for Frenchcinéaste François Truffaut, who directed, co-wrote, and played a central roleas, bien sûr!, a director. (The film’s original title is the term thatis the French equivalent of “day for night”: La Nuit américaine. How apt that this wholly artificialbut often cost-effective process is linked to American savvy.)

In this film about the makingof a romantic melodrama called Je vous présente Paméla (or MeetPamela), Truffaut takes a loving look at the very essence of cinema. Filmsmay seem to reflect life as it is lived, but in fact they are wholly dependentupon artifice. So it follows that those who make movies accept—and thriveon—unreality. Like the fact that thepretty girl in the speeding car is—temporarily—a stuntman wearing a dress and awig. That’s why movie sets are (believeme, I know!) little worlds unto themselves, with emotions running wild.Offscreen romantic partnerships can change from day to day, and few in the castand crew are on their best behavior.

Day for Night begins with what seems like an everyday street scenesomewhere in the south of France. Passersby stroll along a leafy avenue, adeliveryman makes his rounds, a woman walks her dog. Then, cut! It all has to be done again . .. and again. As the director and hisloyal assistant try to keep things under control, the film’s stars are creatingtheir own brand of havoc. Jean-Pierre Aumont, as the veteran actorAlexandre, keeps making mysterious trips to the local airport, little knowingthat one of these jaunts will have disastrous consequences. Fellini veteran Valentina Cortese plays Séverine,an ageing actress so worried about her fading looks and diminishing skills thatshe imbibes heavily, leading to an hilarious scene in which she can’t quitemanage to say her lines and open the proper door. (She was ultimately Oscar-nominatedfor this role, and singled out by winner Ingrid Bergman as the more deservingnominee.)

While cast and crew await thearrival from America of leading lady Julie (Jacqueline Bisset), her film spouseAlphonse (Jean-Pierre Léaud) is struggling with an on-again off-again romancewith the novice script girl. (Léaud’s presence will spark a frisson ofrecognition from film buffs who well remember him as the fourteen-year-oldAntoine Doinel at the center of Truffaut’s cinematic breakthrough, 1959’s TheFour Hundred Blows.) When the oh-so-passionate Alphonse discovers his inamoratahas decamped with the hunky stuntman, his agony knows no bounds. He’sdetermined to quit the production on the spot; in placating him, Julieinevitably puts her own new marriage at risk.

My favorite among the minorcharacters may be Joëlle, the assistant director. She’s always at thedirector’s right hand, making smart suggestions when asked, generally takingcare of business. This doesn’t stop her,though, when out in the countryside cleaning up someone else’s mess, fromstripping off her clothes and announcing to a surprised crew member that she’denjoy a quickie. Later, after the scriptgirl’s sudden departure, Joëlle makes her own feelings clear. She can’t imagineleaving a production to pursue a romance. But would she quit a romance for thesake of a production? Bien sûr! AsIrving Berlin once put it, “There’s no people like show people . . . .”

Beverly in Movieland

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers