Bryan Caplan's Blog, page 134

November 12, 2014

Imprisoning Immigrants, by Bryan Caplan

If you read the tables in my last post carefully, you might have noticed that 10.6% of federal inmates - over 20,000 people - are serving time for immigration offenses. This seems very weird. Stereotypes say that illegal immigrants are punished with deportation, not prison. What's going on?

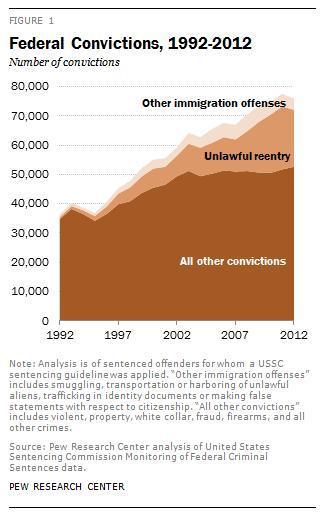

The answer: This stereotype is fast becoming obsolete. Federal imprisonment for illegal immigration has exploded during the last two decades. The numbers, via the Pew Hispanic Trends Project:

The basic facts: First-time illegal immigrants are unlikely to go to prison. But if you're caught, deported, and caught again, you are now fairly likely to be charged with "illegal reentry." Pew's Light, Lopez, and Gonzalez-Barrera explain:

Read the whole Pew piece here.

(5 COMMENTS)

The answer: This stereotype is fast becoming obsolete. Federal imprisonment for illegal immigration has exploded during the last two decades. The numbers, via the Pew Hispanic Trends Project:

The basic facts: First-time illegal immigrants are unlikely to go to prison. But if you're caught, deported, and caught again, you are now fairly likely to be charged with "illegal reentry." Pew's Light, Lopez, and Gonzalez-Barrera explain:

Changes in annual sentencing patterns take a long time to fully show up in overall incarceration numbers, so the 10.6% number is only the tip of a rising iceberg.Between 1992 and 2012, the number of offenders sentenced in federal

courts more than doubled, rising from 36,564 cases to 75,867. At the same time, the number of unlawful reentry convictions increased 28-fold, from 690 cases in 1992 to 19,463 in 2012. The increase in unlawful reentry convictions alone accounts for nearly

half (48%) of the growth in the total number of offenders sentenced in

federal courts over the period. By contrast, the second fastest growing

type of conviction--for drug offenses--accounted for 22% of the growth.

Immigrants charged with unlawful reentry--a federal crime--have entered

or attempted to enter the U.S. illegally more than once. They may also

have attempted to reenter the U.S. after having been officially

deported.

The rising number of convictions for unlawful reentry has altered theIn light of these facts, I'm backing away from my earlier judgment that the difference between deportation and "voluntary returns" is almost entirely cosmetic. I used to think that voluntary returns were about 95% as bad as deportations; now I'd say 85%. Mea culpa.

offense composition of federal offenders. In 2012, immigration

offenses--of which unlawful reentry is the largest category--represented

30% of offenders, up from 5% in 1992.

Unlawful reentry cases alone accounted for 26% of sentenced federal

offenders--second only to drug offenses in 2012. This is up 13-fold since

1992, when offenders sentenced for unlawful reentry made up just 2% of

sentenced offenders.

Read the whole Pew piece here.

(5 COMMENTS)

Published on November 12, 2014 10:12

November 10, 2014

How Many People Does the War on Drugs Put in Prison?, by Bryan Caplan

There are over 1.5 million people in American jails and prisons. Why are they there? Take a look at the latest numbers from the Bureau of Justice Statistics.

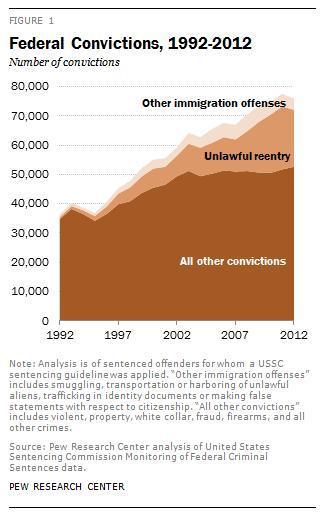

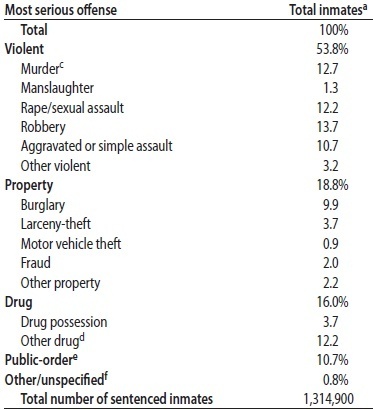

Here is the offense breakdown for state-level incarceration for 2012, which continues to outnumber federal incarceration by a factor of 6:1 or so:

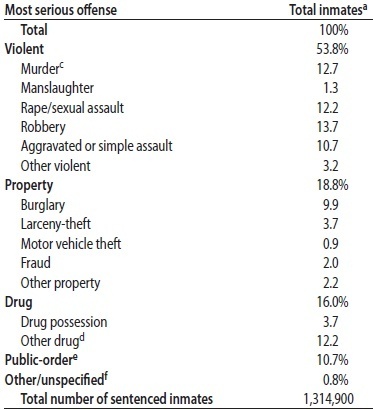

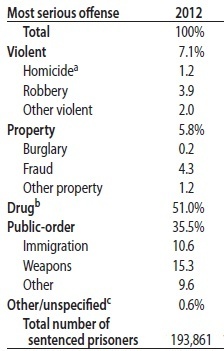

Here's the federal breakdown for 2012:

Most libertarians blame the massive U.S. incarceration rate on the War on Drugs. At the federal level, this is hard to deny. But the federal level remains a small slice of the pie. At the state level, drug offenses are only 16% of the story.

In absolute terms, of course, that's tons of people. Drug offenders outnumber murderers. They outnumber rapists. They outnumber robbers. Indeed, they are only slightly outnumbered by all property criminals combined. But at first glance, blaming the War of Drugs for mass imprisonment runs afoul of basic facts.

What about at second glance? Econ 101 warns us against using mere accounting to resolve causation. In the absence of the War on Drugs, many non-drug offenses would never have been committed. Without prohibition, gang-related violence - and related weapons charges (subsumed under "Public-order" at the state level) - would plummet. Habit-related property crimes would probably do the same, albeit to a smaller degree. Theoretically, drug offenders might simply switch into other illegal activities once drugs were legal, but it's hard to believe this effect would be sizable.

My best guess: Five years after the end of the War on Drugs, half of the prison-years handed out for non-robbery violent crime would be gone, along with 20% of the prison-years for robbery and property crimes, and 75% of the prison-years for weapons charges. That's roughly half of all prison-years at the state level, and two-thirds of all prison-years at the federal level.

Got a better guess? Please share in the comments - and please show your work.

(14 COMMENTS)

Here is the offense breakdown for state-level incarceration for 2012, which continues to outnumber federal incarceration by a factor of 6:1 or so:

Here's the federal breakdown for 2012:

Most libertarians blame the massive U.S. incarceration rate on the War on Drugs. At the federal level, this is hard to deny. But the federal level remains a small slice of the pie. At the state level, drug offenses are only 16% of the story.

In absolute terms, of course, that's tons of people. Drug offenders outnumber murderers. They outnumber rapists. They outnumber robbers. Indeed, they are only slightly outnumbered by all property criminals combined. But at first glance, blaming the War of Drugs for mass imprisonment runs afoul of basic facts.

What about at second glance? Econ 101 warns us against using mere accounting to resolve causation. In the absence of the War on Drugs, many non-drug offenses would never have been committed. Without prohibition, gang-related violence - and related weapons charges (subsumed under "Public-order" at the state level) - would plummet. Habit-related property crimes would probably do the same, albeit to a smaller degree. Theoretically, drug offenders might simply switch into other illegal activities once drugs were legal, but it's hard to believe this effect would be sizable.

My best guess: Five years after the end of the War on Drugs, half of the prison-years handed out for non-robbery violent crime would be gone, along with 20% of the prison-years for robbery and property crimes, and 75% of the prison-years for weapons charges. That's roughly half of all prison-years at the state level, and two-thirds of all prison-years at the federal level.

Got a better guess? Please share in the comments - and please show your work.

(14 COMMENTS)

Published on November 10, 2014 21:04

November 9, 2014

Two Tullock Stories, by Bryan Caplan

Here are my two favorite Gordon Tullock stories, filtered through my admittedly imperfect memory.

Story #1

It's the summer of 1993. Gordon Tullock gives a guest seminar for interns at the Institute for Humane Studies. A random democratic failure comes up, and one of the interns suggests James Buchanan's favorite panacea: "Change the constitution."

I guardedly (yes, guardedly) say: "With all due respect to Professor Tullock, I can't understand why we should expect constitutional politics to work any less badly than day-to-day politics."

Tullock doesn't skip a beat. "You're right, of course. I've never been able to figure out why Jim thinks otherwise. Next question."

[To be fair, Jim does have a drawn-out Veil of Ignorance argument for his view, but it's contrived and implausible - as he once all but admitted.]

Story #2

Fast forward to the early 2000s. Both Tullock and I are now professors at GMU. As you may have heard, Tullock often expressed affection with bizarre insults. After six months, he had yet to speak a word against me. I naturally start to wonder if he dislikes me. All doubt vanishes, though, during a post-seminar dinner with me, Tullock, and Donald Wittman. Tullock is recounting one of his many lessons on Chinese history, ending with, "Chiang Kai-shek was a butcher, but he wasn't as bad as Hitler or Stalin."

Then Tullock stares right at me and says, "You're as bad as Hitler or Stalin. But not Chiang Kai-shek."

I furrow my brow, then remember that for Tullock, the greater and more random the insult, the deeper the affection. I can't recall if I actually said or merely thought, "I love you, too, Gordon."

And if this makes no sense to you, you didn't know Tullock!

(1 COMMENTS)

Story #1

It's the summer of 1993. Gordon Tullock gives a guest seminar for interns at the Institute for Humane Studies. A random democratic failure comes up, and one of the interns suggests James Buchanan's favorite panacea: "Change the constitution."

I guardedly (yes, guardedly) say: "With all due respect to Professor Tullock, I can't understand why we should expect constitutional politics to work any less badly than day-to-day politics."

Tullock doesn't skip a beat. "You're right, of course. I've never been able to figure out why Jim thinks otherwise. Next question."

[To be fair, Jim does have a drawn-out Veil of Ignorance argument for his view, but it's contrived and implausible - as he once all but admitted.]

Story #2

Fast forward to the early 2000s. Both Tullock and I are now professors at GMU. As you may have heard, Tullock often expressed affection with bizarre insults. After six months, he had yet to speak a word against me. I naturally start to wonder if he dislikes me. All doubt vanishes, though, during a post-seminar dinner with me, Tullock, and Donald Wittman. Tullock is recounting one of his many lessons on Chinese history, ending with, "Chiang Kai-shek was a butcher, but he wasn't as bad as Hitler or Stalin."

Then Tullock stares right at me and says, "You're as bad as Hitler or Stalin. But not Chiang Kai-shek."

I furrow my brow, then remember that for Tullock, the greater and more random the insult, the deeper the affection. I can't recall if I actually said or merely thought, "I love you, too, Gordon."

And if this makes no sense to you, you didn't know Tullock!

(1 COMMENTS)

Published on November 09, 2014 21:09

November 6, 2014

Crime, Education, and the NLSY: The Role of the Sheepskin Effect, by Bryan Caplan

Most of the payoff from education comes from credentials, not mere years of class time, a regularity known as the sheepskin effect. A quick look at crime as a function of education suggests a strong sheepskin effect for crime as well.

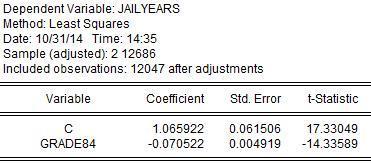

Are appearances revealing? I decided to see for myself in the NLSY. For convenience, I only look at the discrete effect of high school graduation, and equate "high school graduate" with "finished 12th grade." My measure of crime continues to be the total number of times the respondent was interviewed in jail.

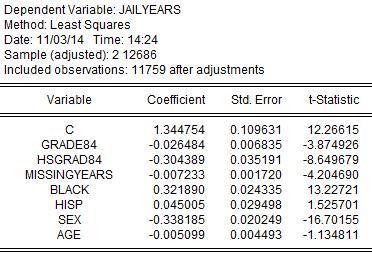

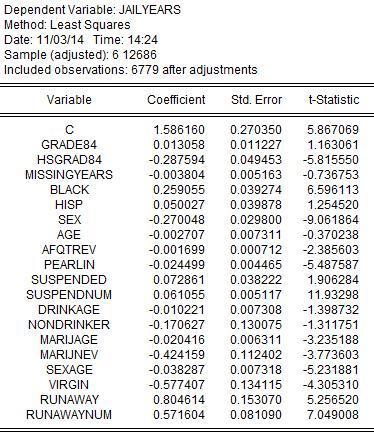

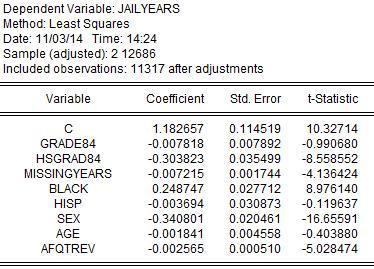

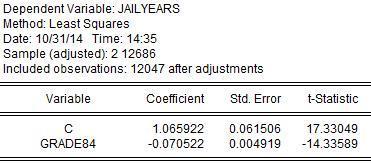

Baseline results confirm a massive sheepskin effect:

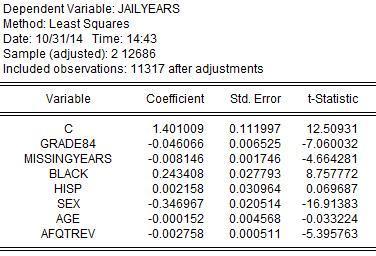

For a four-year high school degree, this implies that the last year of high school provides 80% of the crime reduction effect. How robust is this result? Controlling for demographics and missing residential information makes little difference.

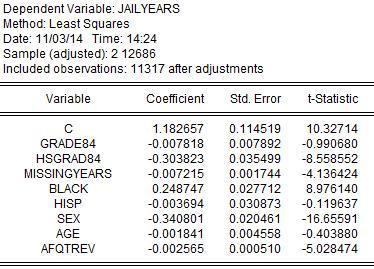

After adjusting for measured intelligence, however, virtually nothing is left except the sheepskin effect!

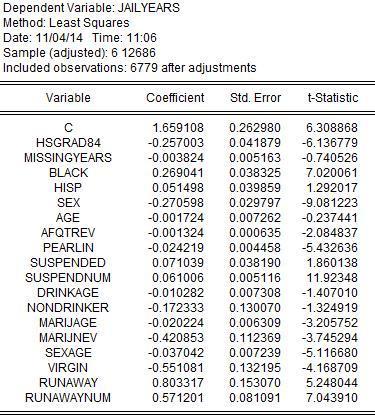

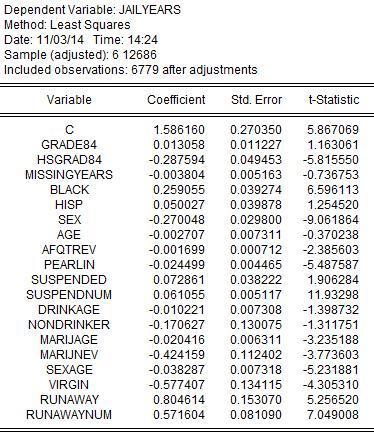

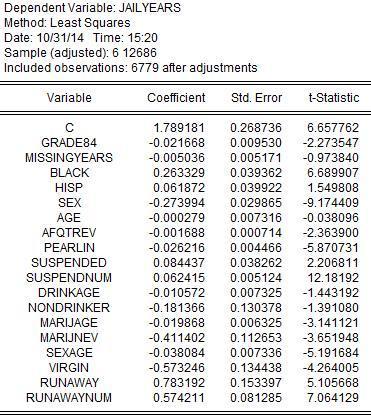

After adjusting for attitudes and teen behavior, continuous years of education actually seem to slightly increase incarceration:

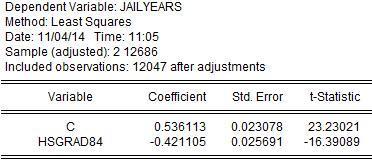

Of course, the criminogenic effect of years of education is neither statistically significant nor plausible. What happens if we simply discard years of education as a control variable? Then the baseline regression becomes:

With all the control variables, this morphs into:

Punchline: All of the effect of education on incarceration looks like a sheepskin effect, but about 40% of that sheepskin effect goes away after taking intelligence, attitudes, and risky teen behavior into account.

If, like me, you view sheepskin effects as a strong symptom of signaling, this means that the selfish and social effects of education on crime sharply diverge. Getting your kid to finish high school genuinely reduces his expected jail time, albeit by markedly less than meets the eye. Socially speaking, however, trying to fight crime by getting everyone to finish high school is futile. The more degrees people have, the more degrees people need to get a good job. So regardless of the average education level, you should expect many young men at the bottom of the educational pecking order to continue to opt for crime over honest toil.

P.S. If worker quality exogenously increases, as I've explained before, we should expect education to go up and crime to go down. Rising education - even rising useless education - can be a symptom of social progress. But that doesn't mean that rising education is progress.

(0 COMMENTS)

Are appearances revealing? I decided to see for myself in the NLSY. For convenience, I only look at the discrete effect of high school graduation, and equate "high school graduate" with "finished 12th grade." My measure of crime continues to be the total number of times the respondent was interviewed in jail.

Baseline results confirm a massive sheepskin effect:

For a four-year high school degree, this implies that the last year of high school provides 80% of the crime reduction effect. How robust is this result? Controlling for demographics and missing residential information makes little difference.

After adjusting for measured intelligence, however, virtually nothing is left except the sheepskin effect!

After adjusting for attitudes and teen behavior, continuous years of education actually seem to slightly increase incarceration:

Of course, the criminogenic effect of years of education is neither statistically significant nor plausible. What happens if we simply discard years of education as a control variable? Then the baseline regression becomes:

With all the control variables, this morphs into:

Punchline: All of the effect of education on incarceration looks like a sheepskin effect, but about 40% of that sheepskin effect goes away after taking intelligence, attitudes, and risky teen behavior into account.

If, like me, you view sheepskin effects as a strong symptom of signaling, this means that the selfish and social effects of education on crime sharply diverge. Getting your kid to finish high school genuinely reduces his expected jail time, albeit by markedly less than meets the eye. Socially speaking, however, trying to fight crime by getting everyone to finish high school is futile. The more degrees people have, the more degrees people need to get a good job. So regardless of the average education level, you should expect many young men at the bottom of the educational pecking order to continue to opt for crime over honest toil.

P.S. If worker quality exogenously increases, as I've explained before, we should expect education to go up and crime to go down. Rising education - even rising useless education - can be a symptom of social progress. But that doesn't mean that rising education is progress.

(0 COMMENTS)

Published on November 06, 2014 21:05

November 4, 2014

Gordon Tullock, 1922-2014, by Bryan Caplan

I am saddened to report that the great Gordon Tullock, professor emeritus at GMU econ and law, has died. While I often disagreed with him, everything he wrote is worth reading. Start with this excellent compendium. Unlike many "interdisciplinary" economists, Tullock was a genuine polymath; his knowledge of history was especially impressive.

Personally, Tullock often outraged and offended others, but I found his deadpan iconoclasm most endearing. He may be the most forthright man I ever met. What a guy.

P.S. It's not too late for the Nobel committee to award its first posthumous Nobel. If anyone deserved it, Gordon did.

(0 COMMENTS)

Published on November 04, 2014 15:55

Me in NYC on Thursday, by Bryan Caplan

This Thursday I'm speaking at the monthly Junto meeting in New York City on "The Case Against Education." Open to the public, hope to see you there.

(1 COMMENTS)

(1 COMMENTS)

Published on November 04, 2014 10:51

November 3, 2014

Crime, Education, and the NLSY: The Role of Ability Bias, by Bryan Caplan

I doubt

The Case Against Education

will spend more than two pages on the effect of education on crime. But I've already spent a month getting ready to write those two pages. Why so long? Because (a) so much has been written on the topic, yet (b) researchers rarely report the precise numbers I want, so I'm also supplementing some of their statistical work to get a better handle on what's going on.

What am I looking for? Estimates of the effect of education on crime that take both ability bias and signaling seriously. So first, I want to see regressions of criminality on education and a wide variety of control variables - cognitive, attitudinal, behavioral, and social. Second, I want to see "sheepskin" regressions that estimate criminality as a function of both discrete credentials and continuous educational attainment measures.

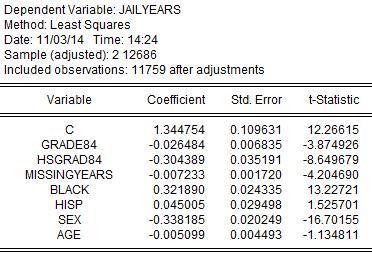

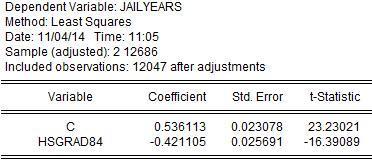

Let me share some of the main ability bias results I've been extracting from the NLSY. Whenever this famous, long-running data set re-interviews respondents - typically every one or two years - it notes their current place of residence. One of those residential options is "Jail." If you regress the total number of times the respondent was interviewed in jail on his years of education, you get:

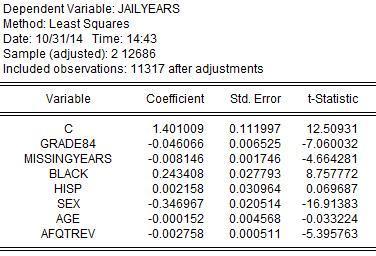

Naively interpreted, every extra year of education leads you to spend .07 fewer interviews in jail. Adding in demographics, plus a measure of observations with missing residential information, makes little difference:

What about controlling for measured intelligence in the form of the AFQT?

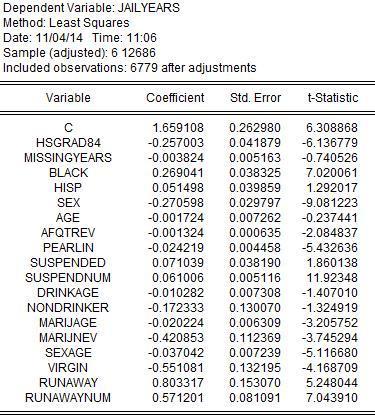

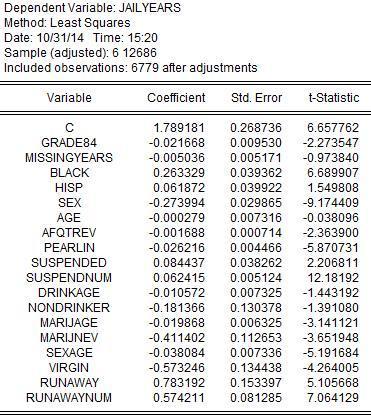

So far, the effect of education on criminality looks pretty robust - two-thirds of the initial effect remains. But what if we add a bunch of "non-cognitive" controls? In particular, what if we adjust for scores on the Pearlin Mastery Scale, as well as suspensions from school, drinking, marijuana use, sex, and running away from home?

Aside: For many of these variables, the NLSY measures not just what you did, but how early and/or how often you did it. SUSPENDED is 1 if you were ever suspended; SUSPENDNUM is the number of times you were suspended. SEXAGE is the age you first had sex; VIRGIN is whether you had ever had sex at the time of the survey. You get the idea.

Behold. With a little statistical elbow grease, the estimated effect of education on incarceration falls by over 2/3rds. Critics of The Bell Curve will eagerly point out that, adjusting for everything else, measured intelligence (AFQTREV) is only a marginal issue. But this doesn't mean that education is all-important, or that ability bias can be safely ignored. Instead, there are a bunch of high-risk teen behaviors that simultaneously lead to educational failure and the slammer - most notably suspension, running away from home, and having sex. If you're the kind of kid who defies adult expectations, whether you actually stay in school is much less important than it looks.

Coming soon: Crime and the sheepskin effect in the NLSY

(9 COMMENTS)

What am I looking for? Estimates of the effect of education on crime that take both ability bias and signaling seriously. So first, I want to see regressions of criminality on education and a wide variety of control variables - cognitive, attitudinal, behavioral, and social. Second, I want to see "sheepskin" regressions that estimate criminality as a function of both discrete credentials and continuous educational attainment measures.

Let me share some of the main ability bias results I've been extracting from the NLSY. Whenever this famous, long-running data set re-interviews respondents - typically every one or two years - it notes their current place of residence. One of those residential options is "Jail." If you regress the total number of times the respondent was interviewed in jail on his years of education, you get:

Naively interpreted, every extra year of education leads you to spend .07 fewer interviews in jail. Adding in demographics, plus a measure of observations with missing residential information, makes little difference:

What about controlling for measured intelligence in the form of the AFQT?

So far, the effect of education on criminality looks pretty robust - two-thirds of the initial effect remains. But what if we add a bunch of "non-cognitive" controls? In particular, what if we adjust for scores on the Pearlin Mastery Scale, as well as suspensions from school, drinking, marijuana use, sex, and running away from home?

Aside: For many of these variables, the NLSY measures not just what you did, but how early and/or how often you did it. SUSPENDED is 1 if you were ever suspended; SUSPENDNUM is the number of times you were suspended. SEXAGE is the age you first had sex; VIRGIN is whether you had ever had sex at the time of the survey. You get the idea.

Behold. With a little statistical elbow grease, the estimated effect of education on incarceration falls by over 2/3rds. Critics of The Bell Curve will eagerly point out that, adjusting for everything else, measured intelligence (AFQTREV) is only a marginal issue. But this doesn't mean that education is all-important, or that ability bias can be safely ignored. Instead, there are a bunch of high-risk teen behaviors that simultaneously lead to educational failure and the slammer - most notably suspension, running away from home, and having sex. If you're the kind of kid who defies adult expectations, whether you actually stay in school is much less important than it looks.

Coming soon: Crime and the sheepskin effect in the NLSY

(9 COMMENTS)

Published on November 03, 2014 21:12

November 2, 2014

Two Skeptical Questions About State Capacity, by Bryan Caplan

Many economists I know, especially the fans of Douglas North, appeal to the concept of "state capacity" to explain economic development, human rights, health, and other social outcomes. In their stories, with few exceptions, high state capacity leads to good things, low state capacity leads to bad things.

Lurking in the background is what I call the the naive Statist Theory of Everything. Why does society X have good thing Y? Because society X's awesome government provided Y. Why doesn't society Z have good thing Y? Because society Z's crummy government failed to provide Y.

As far as I can tell, the state capacity story is supposed to differ from the Statist Theory of Everything. But only obvious difference is packaging: advocates of the state capacity theory tend to decorate their story with mild libertarian sympathies. More substantial differences are hard to detect. Yes, you could say, "I'm not saying that society X has good thing Y because its awesome government provided Y. I'm saying that society X has good thing Y because its government has the capacity to provide good things of all sorts." But this answer seems at once vague and evasive.

Of course, the state capacity story's tension with the libertarian worldview isn't much of an argument against it. Yet faced with the state capacity story, you would at least expect social scientists - regardless of their political leanings - to raise their two standard skeptical challenges to every explanatory concept. Namely:

1. Appeals to "state capacity" sound tautologous: "Why did state X provide good thing Y? Because it has the capacity to provide good things like Y." So if you're going to use state capacity to explain the world, you first need to convince me it's more than mere post hoc tautology.

2. Assuming state capacity isn't mere tautology, it's presumably going to correlate strongly with a bunch of other good things - current per-capita GDP, a long history of per-capita GDP, social trust, public opinion, cultural closeness to other successful societies, etc. So if you're going to use state capacity to explain the world, you also need to convince me that state capacity, rather than any of its blatant correlates, has a big independent effect.

I admit I haven't read widely in the state capacity literature. Most of what I know comes from listening to lunch conversations from aficionados of the approach. Perhaps my elementary challenges have long since been acknowledged and addressed. If so, please share in the comments. I'm all ears - but please tell me you've got something better than the settler mortality stuff.

(10 COMMENTS)

Lurking in the background is what I call the the naive Statist Theory of Everything. Why does society X have good thing Y? Because society X's awesome government provided Y. Why doesn't society Z have good thing Y? Because society Z's crummy government failed to provide Y.

As far as I can tell, the state capacity story is supposed to differ from the Statist Theory of Everything. But only obvious difference is packaging: advocates of the state capacity theory tend to decorate their story with mild libertarian sympathies. More substantial differences are hard to detect. Yes, you could say, "I'm not saying that society X has good thing Y because its awesome government provided Y. I'm saying that society X has good thing Y because its government has the capacity to provide good things of all sorts." But this answer seems at once vague and evasive.

Of course, the state capacity story's tension with the libertarian worldview isn't much of an argument against it. Yet faced with the state capacity story, you would at least expect social scientists - regardless of their political leanings - to raise their two standard skeptical challenges to every explanatory concept. Namely:

1. Appeals to "state capacity" sound tautologous: "Why did state X provide good thing Y? Because it has the capacity to provide good things like Y." So if you're going to use state capacity to explain the world, you first need to convince me it's more than mere post hoc tautology.

2. Assuming state capacity isn't mere tautology, it's presumably going to correlate strongly with a bunch of other good things - current per-capita GDP, a long history of per-capita GDP, social trust, public opinion, cultural closeness to other successful societies, etc. So if you're going to use state capacity to explain the world, you also need to convince me that state capacity, rather than any of its blatant correlates, has a big independent effect.

I admit I haven't read widely in the state capacity literature. Most of what I know comes from listening to lunch conversations from aficionados of the approach. Perhaps my elementary challenges have long since been acknowledged and addressed. If so, please share in the comments. I'm all ears - but please tell me you've got something better than the settler mortality stuff.

(10 COMMENTS)

Published on November 02, 2014 21:01

October 30, 2014

Does Identity Politics Pay?, by Bryan Caplan

When I scoff at group identity, critics often call me naive. Won't anyone who heeds my advice to eschew identity politics end up being victimized by all the folks who do take their group identities with utmost seriousness? Then rational self-interest requires identity politics in self-defense.

The rational self-interest version of this story is trivial to refute. In modern, anonymous societies like our own, all forms of political action are, selfishly speaking, a complete waste of time. This is basic Mancur Olson. You're one person out of billions. Selling your soul to identity politics is astronomically unlikely to noticeably change public policy.

Fortunately, there's a smarter version of the same story. Sure, identity politics is individually fruitless. But won't groups that embrace identity politics fare better than groups that don't?

Maybe. But there are three big reasons to doubt it.

First, there's opportunity cost. The time that members of your group devote to politics is time those members aren't devoting to personal advancement. As Thomas Sowell pointedly observes:

Third, activists' beliefs about the effects of public policies are often deeply confused. So even if identity politics gives your group total power, the results could easily be disastrous for your group. See the sad history of decolonization.

None of this proves that identity politics never pays. My point, rather, is that identity politics is unreliable at best. When you put your childish identity aside, you aren't just sparing yourself; you could easily be doing your former compatriots a favor, too. As far as anyone knows, nobility is a free lunch.

(17 COMMENTS)

The rational self-interest version of this story is trivial to refute. In modern, anonymous societies like our own, all forms of political action are, selfishly speaking, a complete waste of time. This is basic Mancur Olson. You're one person out of billions. Selling your soul to identity politics is astronomically unlikely to noticeably change public policy.

Fortunately, there's a smarter version of the same story. Sure, identity politics is individually fruitless. But won't groups that embrace identity politics fare better than groups that don't?

Maybe. But there are three big reasons to doubt it.

First, there's opportunity cost. The time that members of your group devote to politics is time those members aren't devoting to personal advancement. As Thomas Sowell pointedly observes:

Groups that rose from poverty to prosperity seldom did so by havingSecond, ramping up your side's identity politics often has the perverse side effect of inspiring rival groups' identity politics. Making your group angry and scary can yield lots of goodies if no other group reacts. But the angrier and scarier your group gets, the more likely other groups are to respond in kind. Net effect? Unclear, as usual. And if you instantly exclaim, "So we need to get really angry and scary to make our rival groups back down!" you've utterly missed the point.

racial or ethnic leaders. While most Americans can easily name a number

of black leaders, current or past, how many can name Asian American

ethnic leaders or Jewish ethnic leaders?

Third, activists' beliefs about the effects of public policies are often deeply confused. So even if identity politics gives your group total power, the results could easily be disastrous for your group. See the sad history of decolonization.

None of this proves that identity politics never pays. My point, rather, is that identity politics is unreliable at best. When you put your childish identity aside, you aren't just sparing yourself; you could easily be doing your former compatriots a favor, too. As far as anyone knows, nobility is a free lunch.

(17 COMMENTS)

Published on October 30, 2014 22:03

October 29, 2014

The Identity of Shame, by Bryan Caplan

Every large, unselective group includes some villains. Say whatever you like about the average moral caliber of Christians, atheists, Democrats, Republicans, plumbers, comic book fans, or Albanians. The fact remains that each of these groups contains some awful people. While this isn't logically necessary, it is an iron statistical law. If X has more than a few dozen members, and you can join group X by (a) being born into X, or (b) saying "I'm an X," then X will have some unsavory characters.

When you identify with a large, unselective group, you expose yourself to two dangers. First, some of the villains in your group may take villainous actions that make you look bad. Yet on reflection, that's a minor concern: Yes, the bad members of your group make you look bad, but the good members of your group make you look good.

The second danger is more severe. Once you identify with any large, unselective group, you will be regularly tempted to commit the villainous act of standing up for your groups' villains. When they do wrong - as they inevitably will - your impulse will be to ignore, minimize, or justify their misdeeds. To quote the underrated 8mm , "If you dance with the devil, the devil don't change. The devil changes you."

Look at any large, unselective group you don't identify with. You see them clearly, do you not? Some of its members are plainly bad people. But getting the regular members to unequivocally condemn their bad members is almost impossible. Evolution has honed their myside bias for millions of years, and that's not about to change.

Fortunately, there are relatively easy ways to avoid these temptations in the first place - to save yourself from all shameful identities. Namely: Never identify with large, unselective groups! Instead, restrict your identity to groups that are small, selective, or both.

The nuclear family is the classic small, unselective group; no other group is more deeply founded in human nature. Fortunately, the moral risk of being part of such a family is usually small. Even if you have five kids, there a good chance that none of them will be horrendous people. Circles of friends are the classic small, selective group. Pick your friends carefully, and you probably won't end up an apologist for evil.

Large, selective groups a riskier. In principle, they can evade statistical villainy by carefully vetting and excommunicating questionable members. Unfortunately, myside bias tends to gut the excommunication process. Fringe movements like Jehovah's Witnesses expel members all the time, but not the Catholic Church.

The best way to guard against this laxity is to define your large, selective groups in purely intellectual terms. Identify with liberalism or conservatism, not liberals or conservatives. This is the kernel of truth behind the "No True Scotsman" fallacy. Once you insist that "No true libertarian believes in immigration restrictions," you'll feel little temptation to ignore, minimize, or justify libertarians who believe in immigration restrictions. And this is precisely how you should feel.

Can anyone really live up to my puritanical advice? Yes. Take me. I identify with my nuclear family, with my friends, and with a bunch of ideas. I neither need nor want any broader identity. I was born in America to a Democratic Catholic mother and a Republican Jewish father, but none of these facts define me. When Americans, Democrats, Republicans, Catholics, and Jews commit misdeeds - as they regularly do - I feel no shame and offer no excuses. Why? Because I'm not with them.

(14 COMMENTS)

When you identify with a large, unselective group, you expose yourself to two dangers. First, some of the villains in your group may take villainous actions that make you look bad. Yet on reflection, that's a minor concern: Yes, the bad members of your group make you look bad, but the good members of your group make you look good.

The second danger is more severe. Once you identify with any large, unselective group, you will be regularly tempted to commit the villainous act of standing up for your groups' villains. When they do wrong - as they inevitably will - your impulse will be to ignore, minimize, or justify their misdeeds. To quote the underrated 8mm , "If you dance with the devil, the devil don't change. The devil changes you."

Look at any large, unselective group you don't identify with. You see them clearly, do you not? Some of its members are plainly bad people. But getting the regular members to unequivocally condemn their bad members is almost impossible. Evolution has honed their myside bias for millions of years, and that's not about to change.

Fortunately, there are relatively easy ways to avoid these temptations in the first place - to save yourself from all shameful identities. Namely: Never identify with large, unselective groups! Instead, restrict your identity to groups that are small, selective, or both.

The nuclear family is the classic small, unselective group; no other group is more deeply founded in human nature. Fortunately, the moral risk of being part of such a family is usually small. Even if you have five kids, there a good chance that none of them will be horrendous people. Circles of friends are the classic small, selective group. Pick your friends carefully, and you probably won't end up an apologist for evil.

Large, selective groups a riskier. In principle, they can evade statistical villainy by carefully vetting and excommunicating questionable members. Unfortunately, myside bias tends to gut the excommunication process. Fringe movements like Jehovah's Witnesses expel members all the time, but not the Catholic Church.

The best way to guard against this laxity is to define your large, selective groups in purely intellectual terms. Identify with liberalism or conservatism, not liberals or conservatives. This is the kernel of truth behind the "No True Scotsman" fallacy. Once you insist that "No true libertarian believes in immigration restrictions," you'll feel little temptation to ignore, minimize, or justify libertarians who believe in immigration restrictions. And this is precisely how you should feel.

Can anyone really live up to my puritanical advice? Yes. Take me. I identify with my nuclear family, with my friends, and with a bunch of ideas. I neither need nor want any broader identity. I was born in America to a Democratic Catholic mother and a Republican Jewish father, but none of these facts define me. When Americans, Democrats, Republicans, Catholics, and Jews commit misdeeds - as they regularly do - I feel no shame and offer no excuses. Why? Because I'm not with them.

(14 COMMENTS)

Published on October 29, 2014 22:24

Bryan Caplan's Blog

- Bryan Caplan's profile

- 374 followers

Bryan Caplan isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.