Bryan Caplan's Blog, page 130

January 15, 2015

Correction on Abortion, by Bryan Caplan

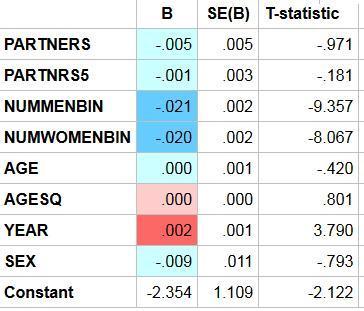

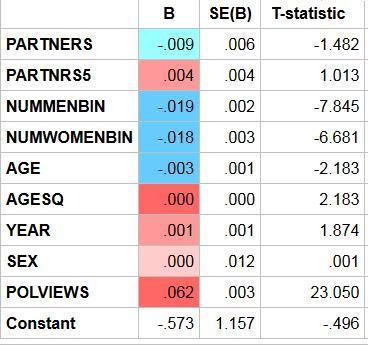

The noble Sam Wilson pointed out a problem with this morning's abortion regressions. My dependent variable, ABORTION, was constructed by another GSS user. This user coded people who weren't asked about abortion as "no's." The true yes/no split on "abortion for any reason" is 41/59. Here are the corrected regressions using ABANY as the dependent variable.

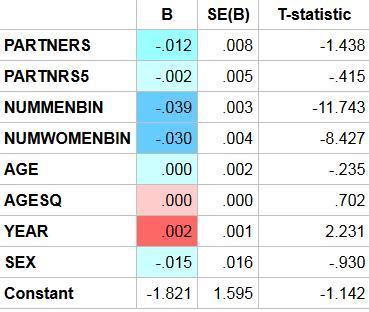

Regressing abortion views on sexual partners, age, age squared, year, and sex:

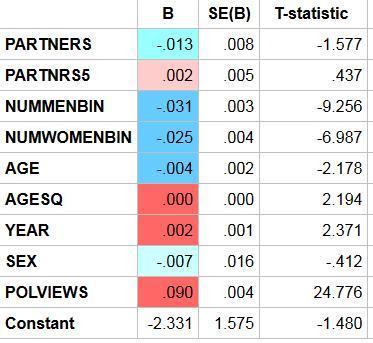

Adding a control for ideology:

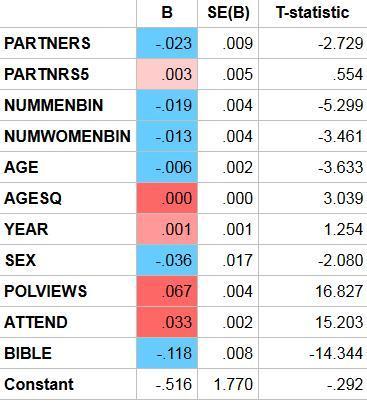

Adding controls for church attendance and Biblical literalism:

Main change: The absolute magnitude of all the main coefficients rises by roughly 50%, leaving the relative role of ideas and interests about the same. Main difference: Number of male sexual partners now looks about 50% more important than number of female sexual partners.

Still, I messed up, and I apologize.

(0 COMMENTS)

January 14, 2015

How Selfish Are Our Views About Abortion?, by Bryan Caplan

In The Hidden Agenda of the Political Mind, Weeden and Kurzban argue that individuals' "inclusive interests" have a large effect on their position on abortion. On the one hand, this seems implausible. On the other hand, Jason Weeden wrote his dissertation on abortion attitudes, so there must be something to his story. What's really going on? Like Weeden and Kurzban, I turn to the General Social Study to find out. My evidence is only exploratory; I don't pursue every statistical permutation. However, I did precommit to blog the topic before I looked at the data.

Recall Weeden and Kurzban's novel claim:

People who party and sleep around have an interest in other people notThe GSS has many measures of abortion opinion, but the best is probably ABORTION, which =1 if the respondent thinks abortion should be legal for any reason, and =2 otherwise. Given the starkness of the former position, it's not too surprising that the split is 23/77.

bringing legal or moral costs to bear on them for doing so. People who

want to delay having children while partying and sleeping around have an

interest in the availability of family planning, including the backstop

of legal abortion. Their mental Boards of Directors will prefer moral

and political policies that help them live the lives they want to live.

The GSS also has many measures of sexual activity.* Taking both relevance and missing data into account, the best measures are probably:

1. Number of sexual partners in the last year (PARTNERS), binned into 8 categories: 0=no partners, 1=1 partner, 2=2 partners, 3=3

partners, 4=4 partners, 5=5-10 partners, 6=11-20 partners, 7=21-100

partners, 8=100+ partners.

2. Number of sexual partners in the last five years (PARTNRS5), binned into the same 8 categories as PARTNERS.

3. Lifetime number of male sexual partners (NUMMEN) and female sexual partners (NUMWOMEN). These measures are continuous, but I recode responses into the same 8 bins as the two previous variables. The recoded variables are NUMMENBIN and NUMWOMENBIN.

So what happens if we regression ABORTION on a constant, all four measures of sexual activity, age, age squared, year, and SEX (=1 if male, =2 if female)?

Weeden and Kurzban are seemingly on to something. Every step up the ladder of lifetime partners makes respondents about 2 percentage-points more pro-choice. Strangely, though, number of partners in the past year and past five years make very little difference; their coefficients are statistically insignificant even though there are over 15,000 valid observations. In terms of self-interest, of course, you'd expect recent sexual behavior to matter more.

But what happens if we control self-reported ideology, which runs from 1 (most liberal) to 7 (most conservative)? This.

Left-right ideology is far more important than number of sexual partners. A single step on the 1-7 ideology ladder matters more than three steps on the lifetime sexual partners ladder. A liberal virgin is more pro-choice than a conservative with over 100 lifetime partners.

What about religion? Weeden and Kurzban want to count church attendance as a measure of interests. The GSS variable is ATTEND, which ranges from 0 (never attends religious services) to 8 (attends more than once per week). But once you're controlling for all four measures of sexual partners, it's hard to see why attendance continues to be a credible measure of sexual risk-taking. In any case, Weeden and Kurzban neglect a more philosophical GSS measure of religiosity: your views on the Bible. Response options:

1. The Bible is the actual word of God and is to be taken literally, word for word.What happens if we add ATTEND and BIBLE to the list of explanatory variables?

2. The Bible is the

inspired word of God but not everything in it should be taken literally, word for word.

3. The Bible is an ancient book of

fables, legends, history, and moral precepts recorded by men.

Left-right ideology remains the strongest predictor, but both religious measures are comparably important. The coefficients on sexual activity are miniscule by comparison. Moving from a moderate Christian to a fundamentalist Christian view of the Bible has a bigger effect than moving from 0 to 100+ lifetime sexual partners.

Since Weeden wrote his dissertation on this topic, he surely knows this data better than I do. Still, I'll be very surprised if he can add anything to my final regression that makes interests look more important than ideas. If he posts any such regressions, you'll be the first to know.

P.S. As far as I can tell, GenCon attendees are liberal and irreligious yet have few sexual partners. Does anyone who's attended seriously expect these gamer nerds to be pro-life?

* Weeden and Kurzban have a bunch of other measures of the

"Freewheeling" lifestyle, but it's hard to see how they remain relevant to the interest-abortion

nexus after controlling for number of sexual partners. For example, one of

their explanatory variables is how often respondents visit bars. But

after controlling for number of sexual partners, it's hard to see how

abortion serves the interests of barflies.

(5 COMMENTS)

January 13, 2015

Rejoinder to Weeden, by Bryan Caplan

During last week's visit to LA, I was able to meet up with Andrew Healy, David Henderson, Charley Hooper, Brian Doherty, David Gordon, and Alex Epstein. Meanwhile, in cyberspace, Jason Weeden has been energetically replying to my critiques of his and Kurzban's The Hidden Agenda of the Political Mind. In fact, he's replied to all three of my posts: me/him, me/him, me/him. After reading his replies, I don't have lots to add to my original critiques. But here are a few objections to his main reply. Weeden's in blockquotes, I'm not.

There's a real danger here of talking past each other. In his review, Caplan points to his lecture outline on self-interest in politics.

In it, he says he interprets "'people are self-interested' as 'on

average, people are at least 95% selfish.'" This is an incredibly high

bar.

Most behavior in markets seems to meet this >95% bar. Americans, charitable by world standards, only donate about 3% of their pretax income. And much of that "charity" goes to churches, schools, and other clubs that give donors substantial private benefits in exchange. I don't recall any admission in Weeden and Kurzban that, even if they're right, people are much less selfish in politics than in markets.

This difference leads to some confusion. Caplan, for example, claims

that we do not admit that "non-interest-based ideology" affects people's

views. This is contradicted by our explicit remarks on this topic. For

instance, on page 206 we wrote: "When it comes to party identifications

and ideological labels, we think they can exert substantial causal

influence on a range of judgments." This admission doesn't compromise

our central point, though, since we never said that ideology doesn't

matter at all or is entirely about self-interest. Instead, our project

was to look at whether self-interest has substantial effects on public

opinion, regardless of what else might matter.

Hardly. Weeden and Kurzban repeatedly claim that ideology summarizes interests, so it's natural to read their admissions in this light.

Caplan says that we "trumpet a strong, incredible thesis, then

'interpret' virtually every fact to fit it" and that we "never clearly

state what would count as evidence against their view." I could say the

same of Caplan's book, The Myth of the Rational Voter.

Nope. Most obviously, I have a ton of regressions where I'm (a) right if experts and laymen disagree a lot on average, (b) exaggerating if experts and laymen only disagree a little on average, and (c) wrong if experts and laymen agree on average.

Our agenda was not exclusively to try to falsify our own view, just

as Caplan's agenda was not exclusively to try to falsify his own.

"Exclusively trying to falsify your own view" is indeed a silly approach. My complaint about Weeden and Kurzban is that they make near-zero effort to falsify their own view until the final chapter, when they discuss two cases - the environment and foreign policy - they perceive as problematic.

Here are some examples. In Caplan's lecture outline,

he says: "Unemployment policy - The unemployed not much more in favor

of relief measures." It's an empirical claim. When we checked the data

in our book, we found that the unemployed were about 29 percentage points

more supportive of unemployment benefits than those working full time.

Similarly, Caplan says: "National health insurance - The rich and people

in good health are about as in favor." In our book, we found that

wealthier people with health insurance were 19 percentage points

less supportive than poorer people without health coverage when it

comes to opinions on whether it ought to be the government's

responsibility to provide health coverage.

Very misleading. All of the studies I'm summarizing report coefficients on self-interested variables after controlling for confounding factors. Weeden and Kurzban actually admit this in their book, but not loudly enough for casual readers to notice.

If these sorts of analyses do not count as evidence against Caplan's view, it's unclear what would.Let me make it clear what would count as evidence against my view: Re-run your regressions with standard control variables like self-identified ideology, and show me that (a) the coefficients on the standard control variables are small, and (b) the coefficients on your measures of self-interest shrink by less than 25%.

Relatedly, Caplan says we believe that one's allies and socialVery well, how big can these "non-related circles" be? 50? 100?

networks consist of "millions of people." This is false. Our point (pp.

38-40) was that individuals often have a tangible stake in what happens

with the actual circle of non-related people with whom they share

benefits and burdens (mostly including romantic partners and close

friends, but also leaking over into co-workers, fellow church members,

etc.). This may be indirect self-interest, but it's certainly not the absence of self-interest.

Again, e.g., if individuals who are

religious minorities tend to oppose discrimination against religious

minorities, it's incoherent to say that that's evidence of an absence of

self-interest. If individuals who engage in casual sex don't want

others imposing social costs on people who engage in casual sex, it's

incoherent to say that that's evidence of an absence of self-interest.

And so on.

I agree that such patterns raise the possibility of a big role for self-interest. But Weeden and Kurzban rush to judgment, while I want a patient investigation. For example: If you think religious minorities oppose employment discrimination out of self-interest, you should compare the opinions of working versus retired religious minorities. If you reply that retired religious minorities care about their kids' job prospects, you need to demonstrate a large belief gap between retired religious minorities with and without children.

Further, Caplan quotes a section where we ourselves discuss

issues we think don't fit with a self-interest account - how can a

tautology produce such results?

Because the tautological reasoning is inconsistent, of course; see my discussion of the motte-and-bailey fallacy.

Of course you can always find ways to make demographic"Always"? No. It's even possible for demographic coefficients to get bigger after controlling for other variables. For example, the belief gap between economists and the public slightly rises after controlling for ideology and party, because economists hold pro-market views despite their leftish tendencies.

coefficients shrink in models of public opinion by "controlling" for

ideology, party affiliation, and various explicitly political scales

(like right-wing authoritarianism, etc.).

Let's say that income, race, and gender combine to predict to a

degree views on redistributive issues. And then let's say that these

coefficients are greatly reduced by "controlling" for ideology, party

affiliation, and so on. Does that mean that income, race, and gender

never mattered in the first place? Does being a conservative Republican

turn poor, minority women into rich, white men? At best, this doesn't

mean that income, race, and gender don't matter, but suggests something

about the manner in which they matter.

So we're back to tautology. By this logic, Weeden and Kurzban would be right even if one-dimensional ideology perfectly predicted all political views.

Caplan says that the book doesn't produce multiple regressions

including "a simple measure of left-right ideology as an explanatory

variable" and that it "never 'races' its thesis against any competing

view." But there were reasons we chose not to run these races. First, I

have big doubts about whether such correlates are in fact primarily

causes rather than effects or non-causal siblings.

When social scientists have such doubts, they usually still run the regressions and report the results. Why don't you?

If you've followed Caplan's work, you'll know that he is deeply

committed to advancing libertarian policy objectives. His argument in

service of this objective is, basically: (1) People mostly just want

what's best for society as a whole. (2) Libertarian economists know

better than others what's best for society as a whole. (3) Therefore,

people should follow the policy advice of libertarian economists.Step 2 might well be true. But, if it turns out step 1 is wrong, and

that political disagreement has a lot to do with competing

constituencies' self-interest, then it's harder to get to step 3.

An interesting theory. But I can assure you that most libertarians disagree with me. Like most people, libertarians love chalking up their opponents' views to self-interest. That's why they're so fond of orthodox public choice theory - and why I've struggled to talk them out of it.

If

low-education native-born folks tend to oppose libertarian immigration

policies because they're often worse off under these policies, then

that's a problem for the argument. Or if low-income people with

low-income social networks tend broadly to favor greater income

redistribution because their own circumstances are advanced, then that's

also a problem.

Not really. I could just as easily argue that people are self-interested, but mistaken about what policies serve their self-interest.

P.S. Rather than keep criticizing Weeden and Kurzban, I'm going to re-do their abortion regressions the way I think they should have been done. I announce this before looking at the data, and will report whatever I find. Stay tuned.

(1 COMMENTS)

January 11, 2015

Freewheelers, Ring-Bearers, and Self-Interest, by Bryan Caplan

Freewheelers include people who sleep with more people, are sexually active outside of committed relationships, have more same-sex partners, party, drink, go to bars, and use recreational drugs more, live together outside of marriage, are less likely to marry at all, get divorced more when they do marry, and have fewer kids. Ring-Bearers include people who wait longer to have sex, tend to have sex only in committed relationships (often waiting until getting engaged or married), go to bars and party less, don't cohabit outside of marriage, have long-lasting marriages, and have more kids.The book then dissects the divergent interests of the two types. The Freewheelers:

People who party and sleep around have an interest in other people not bringing legal or moral costs to bear on them for doing so. People who want to delay having children while partying and sleeping around have an interest in the availability of family planning, including the backstop of legal abortion. Their mental Boards of Directors will prefer moral and political policies that help them live the lives they want to live.The Ring-Bearers:

For young Ring-Bearers, a big problem is finding suitable partners to share Ring-Bearer lives with. Young women asking their boyfriends to wait for sex have to compete with young women offering more immediate rewards. For both sexes, the fewer people fooling around, the more suitable candidates there are for long-term Ring-Bearer relationships.These are some of Weeden and Kurzban's better just-so stories of selfishness. But they're still easy to improve. For starters, as long as you're straight (or even a straight-leaning bisexual), selfishness implies big gender splits within the Freewheeler and Ring-Bearer ideal types.

[...]

For both Ring-Bearer men and women, the chances of maintaining a faithful marriage depend in part on what people around them are doing when it comes to low-commitment sex. Ring-Bearers have an increased interest in minimizing temptations faced by their mates, and the fewer people fooling around, the less likely it is that one's mate will succumb.

An obvious way to make Freewheeling less common is to make it more costly.

If you're a Freewheeling male, you should staunchly oppose legal burdens on female promiscuity. But you should be open to legal burdens on male promiscuity. If a policy burdens all promiscuous males other than yourself, the Freewheeling male should enthusiastically support the burdens. For example, a Freewheeling male who can demonstrate he's had a vasectomy has every selfish reason to ban condoms. Why? Because this gives him a huge competitive edge over all the fertile Freewheeling men. The reverse goes for Freewheeling women. As soon as they get their tubes tied, their self-interest urges them to become pro-life, giving them a competitive edge over all the fertile Freewheeling women.

Analogous results hold for Ring-Bearers. Selfishly speaking, Ring-Bearer men should recoil to see fellow men in church; Ring-Bearer women should recoil to see fellow women in church. Staunch Ring-Bearer men should favor secular sex education for men to reduce the supply of men competing to marry the best Ring-Bearer women; Staunch Ring-Bearer women should favor secular sex education for women to reduce the supply of women competing to marry the best Ring-Bearer men.

Once you account for these subtleties, however, Weeden and Kurzban's original claims seem worse than over-simplified; they could be totally wrong. Consider: Freewheeler men (a) benefit from legal burdens on men other than themselves, (b) lose from legal burdens on themselves, and (c) lose from restrictions on women. Some legislation comes forward that combines (a), (b), and (c). Selfishly speaking, the key question is: "What is the NET effect?" The general answer is: "Unclear." This is a simple extension of what regulatory economists have known for decades: Regulated firms can and often do benefit from regulation, because differential burdens imply benefits.

Here's an additional complexity. Weeden and Kurzban rightly emphasize that Ring-Bearers face a painful uncertainty: Is their spouse only pretending to be a Ring-Bearer? (This is a mild problem for Freewheelers, since they invest little in long-run relationships anyway). Now consider: What would happen if the law persecuted anyone who openly pursued a Freewheeling lifestyle? Freewheelers would obviously respond by acting like Ring-Bearers! This in turn raises Ring-Bearers' risk of accidentally marrying a Freewheeler-in-Ring-Bearer's-clothing. Selfishly speaking, then, Ring-Bearers actually have a strong reason to amiably tolerate their Freewheeler rivals: Libertines are a lesser evil than hypocrites.

You could protest that my predictions about Freewheelers' and Ring-Bearers' opinions are wrong. But that misunderstands what I'm doing. I'm not describing how Freewheelers and Ring-Bearers think. I'm describing how they would think if they were self-interested. My arguments give readers a choice: Embrace bizarre claims about public opinion, or stop claiming that self-interest explains what people think about sexual politics.

(0 COMMENTS)

January 8, 2015

Some Replies to Me, by Bryan Caplan

1. Jason Weeden's reply to my review of The Hidden Agenda of the Political Mind.

2. Nathan Smith's reply to my defense of tolerance.

3. Jason Weeden's reply to me on ideology.

(6 COMMENTS)

January 7, 2015

Plus Noise!, by Bryan Caplan

Economist Bryan Caplan in his book, The Myth of the Rational Voter, asserted (with his tongue in its usual non-cheeky place): "There are countless issues that people care about, from gun control and abortion to government spending and the environment... If you know a person's position on one, you can predict his view on the rest to a surprising degree. In formal statistical terms, political opinions look one-dimensional. They boil down to roughly one big opinion, plus noise."Just one problem: I'm well-aware that the data aren't tidy. Accurately predicting individual opinions is hard. I deliberately included the words "plus noise" to ensure that readers knew I was not claiming great predictive powers.

[...]

If we take the assertions from Caplan and Pinker (not to mention Stewart) seriously, we should be able to take people's view on one of these issues and know their views on the other issue...

The data are decidedly less tidy.

I should add, however, that opinion has more ideological coherence than Weeden and Kurzban claim. Yes, using one specific issue position to predict an unrelated specific issue position is almost fruitless. In the General Social Survey, the correlation between gun control and abortion positions is a mere .02. But using self-identified ideology to predict specific issue positions is noticeably more rewarding. In the GSS, ideology correlates at .11 with gun control views and .22 with abortion views.

Why would this be? Simple. Specific issue views, like individual items on the SAT, are very noisy. Ideology, like overall SAT score, is not so noisy. When you correlate two noisy things with each other, you get a really tiny correlation. When you correlate one noisy thing with a not-so-noisy thing, you get a moderate correlation. If Weeden and Kurzban really wanted to dispute the one-dimensionality of political opinion, they should have been correlating specific issue views with ideology, not specific issue views with each other.

(5 COMMENTS)

January 6, 2015

Intelligence Makes People Think Like Economists: Further Evidence, by Bryan Caplan

[T[he observed relationship between intelligence and conservatism largely depends on how conservatism is operationalized. Social conservatism correlates with lower cognitive ability test scores, but economic conservatism correlates with higher scores (Iyer, Koleva, Graham, Ditto, & Haidt, 2012; Kemmelmeier 2008). Similarly, Feldman and Johnston (2014) find in multiple nationally representative samples that social conservatism negatively predicted educational attainment, whereas economic conservatism positively predicted educational attainment. Together, these results likely explain why both Heaven et al. (2011) and Hodson and Busseri (2012) found a negative correlation between IQ and conservatism--because "conservatism" was operationalized as Right-Wing Authoritarianism, which is more strongly related to social than economic conservatism (van Hiel et al., 2004). In fact, Carl (2014) found that Republicans have higher mean verbal intelligence (up to 5.48 IQ points equivalent, when covariates are excluded), and this effect is driven by economic conservatism (which, as a European, he called economic liberalism, because of its emphasis on free markets). Carl suggests that libertarian Republicans overpower the negative correlation between social conservatism and verbal intelligence, to yield the aggregate mean advantage for Republicans. Moreover, the largest political effect in Kemmelmeier's (2008) study was the positive correlation between anti-regulation views and SAT-V scores, where β = .117, p < .001 (by comparison, the regression coefficient for conservatism was β = −.088, p < .01, and for being African American, β = −.169, p < .001).Those cites:

Carl, N. (2014). Verbal intelligence is correlated with socially and economically liberal beliefs. Intelligence, 44, 142-148.

Feldman, S., & Johnston, C. (2014). Understanding the determinants of political ideology: Implications of structural complexity. Political Psychology, 35(3), 337-358.

Heaven, P. C., Ciarrochi, J., & Leeson, P. (2011). Cognitive ability, right-wing authoritarianism, and social dominance orientation: A five-year longitudinal study amongst adolescents. Intelligence, 39(1), 15-21.

Hodson, G., & Busseri, M. A. (2012). Bright minds and dark attitudes: Lower cognitive ability predicts greater prejudice through right-wing ideology and low intergroup contact. Psychological Science, 23(2), 187-195.

Kemmelmeier, M. (2008). Is there a relationship between political orientation and cognitive ability? A test of three hypotheses in two studies. Personality and Individual Differences, 45, 767-772.

Iyer, R., Koleva, S., Graham, J., Ditto, P., & Haidt, J. (2012). Understanding libertarian morality: The psychological dispositions of self-identified libertarians. PLoS ONE 7(8): e42366. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0042366

Van Hiel, A., Pandelaere, M., & Duriez, B. (2004). The impact of need for closure on conservative beliefs and racism: Differential mediation by authoritarian submission and authoritarian dominance. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30(7), 824-837.

To counter my confirmation bias, please post contrary cites in the comments.

(16 COMMENTS)

January 4, 2015

Conspiracy Theory: The Hidden Agenda of the Political Mind, by Bryan Caplan

Unlike most economists, I strongly endorse political scientists' consensus. Their research doesn't just look solid. I've also personally played with the data for over a thousand hours, confirming that their basic approach is correct. When I teach this material, I make my graduate students hunt for counter-examples - exceptional cases where self-interest is highly predictive of political views. Most return from this quest empty-handed, or nearly so.

Jason Weedon and Robert Kurzban's new The Hidden Agenda of the Political Mind: How Self-Interest Shapes Our Opinions and Why We Won't Admit It (Princeton University Press, 2014) frontally attack the academic consensus against political self-interest. Since they charmingly paint me as a leading voice in this consensus, it is in my self-interest for their book to be widely-read. Unfortunately, Weedon and Kurzban are basically high-brow conspiracy theorists. They trumpet a strong, incredible thesis, then "interpret" virtually every fact to fit it.

This is easier than it sounds because they quickly water their thesis down to near-tautology. After criticizing political scientists for ignoring the power of self-interest, Weedon and Kurzban officially abandon the very word they put on cover of their book! Page 38:

[I]t's probably best to jettison the term "self-interest" altogether... So, we'll refer to "inclusive interests." Something is in a person's "inclusive interests" when it advances their or their family members' everyday, typical goals.If that's not loose enough for you, they stretch the definition again two pages later:

And so our earlier notion of "inclusive interests" needs to be expanded further. People's everyday, real-life endeavors are enhanced by various kinds of material and nonmaterial gains, over shorter-term and longer-term horizons, received by themselves, their family members, and their friends, allies, and social networks.Who are your "allies"? Who's in your "social networks"? Millions of people. Weedon and Kurzban appear to count entire races (including "white") and broad religious categories (including "Christian") as allies and social networks. What about the logic of collective action - the hard fact that helping out amorphous social networks is almost always, selfishly speaking, a waste of time? Though I'm confident the authors grasp this elementary point, they write as if they don't:

If most African Americans support policies that attenuate the negative effects of racial discrimination, and most African Americans benefit from their policies, and few African Americans are harmed by these policies, then we don't see why supporting one's group would be self-sacrificial. We view most examples of things that advance "groups" as basically equivalent to things that advance the individual interests of lots of members of those groups.Structurally, this is no different from denying that blood donation involves self-sacrifice. After all, don't most blood donors benefit from the availability of blood in case they need it? Never mind the Prisoner's Dilemma and the Fallacy of Composition.

Given The Hidden Agenda's expansive definition of "interests," it's not surprising that they find a ton of evidence supporting their position. Single atheists are much more pro-choice than married church-goers? Of course, single atheists have an interest in easy access to abortion. Harvard grads are overwhelmingly Democratic? Of course, because rich workers have an interest in lowering the relative status of rich capitalists. The book goes on and on like this, a parade of just-so stories of selfishness.

In future posts, I'll investigate some of Weedon and Kurzban's empirical results in detail. For now, I'll point out the big conceptual flaws.

1. They never clearly state what would count as evidence against their view. Instead, they dismiss the top competing theories on conceptual grounds. Most notably: As far as I can tell, they never include a simple measure of left-right ideology as an explanatory variable. Why not? Because if their theory is right, ideology is merely an index of interests.

It could be the case, for example, that many people choose to call themselves "liberal" or "conservative" (or "libertarian" or something else or none of the above) based on a kind of summation of their particular policy views.So what measure of non-interest-based ideology would Weedon and Kurzban accept? They provide not a clue.

2. The Hidden Agenda never statistically "races" its thesis against any competing view. When social scientists want to empirically test the view that ideology is merely an index of interests, for example, they normally run a regression of issue positions on (a) detailed measures of interests, and (b) ideology. Then they see if (b) remains important controlling for (a). Weedon and Kurzban do nothing like this, ever. And anyone who knows the data knows why: Ideology usually wins the race by a landslide.

To be fair, The Hidden Agenda measures interests in some novel ways. It's conceivable that their novel measures could actually prevail in a statistical race. But Weedon and Kurzban studiously refuse to allow a contest. This approach would be understandable, if not excusable, if the scholarly consensus were already on their side. But as they freely admit, the opposite it true. When a champion refuses to race, it's suspicious; when a challenger refuses to race, however, it's ludicrous.

3. The Hidden Agenda almost entirely eschews one of their side's standard defensive maneuvers: Retreating from objective interest ("People do whatever is actually in their interest") to subjective interest ("People do whatever they think is in their interest"). To stick with the strong version of their claim, though, they tacitly embrace the absurd view that measuring the effects of public policies is child's play. FYI: It's not. To know whether a higher income tax is in your interest, for example, it's s vital to know the elasticities of labor supply and labor demand. Measuring these elasticities is notoriously difficult. Ignoring this issue lets the authors blithely interpret education and intelligence as proxies for varying interests, never considering the possibility that education and intelligence might lead to more reasonable beliefs about policies' effects.

4. Suppose a person volunteers at a soup kitchen once a week. Every year, the volunteers get one free lunch at McDonald's. A dogmatic believer in the power of self-interest could say, "They volunteer for the Big Macs." A reasonable person, however, would focus on magnitudes: Selfishly speaking, a free lunch at McDonald's is worth vastly less than 52 days of toil. In the real world, of course, weighing magnitudes is rarely so easy. But Weeden and Kurzban seem oblivious to this issue. If rich pro-choice people vote Democratic, The Hidden Agenda summarily concludes that their abortion interests must outweigh their financial interests. How could a tiny reduction in the availability of abortion be worth thousands of dollars per year in extra taxes? Inquiring minds want to know, but Weeden and Kurzban don't tell us.

The Hidden Agenda's final chapter does present two hard cases for their theory: the environment and the military. The challenge: The views of people with no personal connection to the energy or defense industries still vary widely.

These constituencies [folks tied to the energy and defense industries] are too small, however, to explain the outsized role environmental and military issues play in political debates. Why, in short, do so many people only distally affected care so much about these issues? And why have they split out the way they have in terms of competing views? Fights over global warming, renewable energy, interventions in Middle Eastern conflicts, and related areas affect people's everyday lives, but the connections, it seems to us, are unusually remote, and, further, it would have been hard to predict ex ante which people would have wound up on which side.If only Weeden and Kurzban had applied the same skeptical filter to every issue they analyze! Then they might have been appropriately puzzled by a multitude of other facts they document, starting with:

When it comes to spending on the environment, the correlations between people's positions and their demographic traits are modest in size, and don't lend themselves to easy interpretation. People who favor higher environmental spending tend to have more education, not to be regular churchgoers, to be younger and - perhaps most surprisingly - to have no children.

1. Well-educated, secular whites' high support for redistribution (pp.178-82).

2. Men's above-average support for legal abortion (pp.62-3).

3. The elderly's relatively low support for Social Security (p.137).

The Hidden Agenda of the Political Mind is a book-length application of the motte-and-bailey fallacy. Scott Alexander provides the background. In a medieval castle...

...there would be a field of desirable and economically productive landWeeden and Kurzban's put their bailey right on the cover: "How self-interest shapes our opinions and why we won't admit it." When they confront the data, however, this position is utterly indefensible, so they flee to the motte of "inclusive interests," which they interpret to mean virtually anything. Once they peruse the data, they return to the bailey, claiming victory for their daring, contrarian position.

called a bailey, and a big ugly tower in the middle called the motte.

If you were a medieval lord, you would do most of your economic activity

in the bailey and get rich. If an enemy approached, you would retreat

to the motte and rain down arrows on the enemy until they gave up and

went away. Then you would go back to the bailey, which is the place you

wanted to be all along.So the motte-and-bailey doctrine is when you make a bold,

controversial statement. Then when somebody challenges you, you claim

you were just making an obvious, uncontroversial statement, so you are

clearly right and they are silly for challenging you. Then when the

argument is over you go back to making the bold, controversial

statement.

The Hidden Agenda isn't all bad. It has a few nuggets of insight. It also contains many candidate nuggets - novel claims that might prevail in a statistical race against conventional theories. And they treat me very well. Overall, though, this book is an attempt to replace decades of careful and curious social science with near-tautologies and just-so stories. Contrary to its fans, the only "important" thing about this book is that it might destroy a valuable body of knowledge.

(3 COMMENTS)

January 3, 2015

Shy Male Nerds and the Bubble Strategy: Reply to Scott Alexander, by Bryan Caplan

Even on the purely academic/intellectual level, this [Caplan's Bubble stategy] isWith all due respect, this is hard to believe. I've been a nerd for decades. 95% of my friends are male nerds. My friends tend to be unusually young and single because many of them are my former students. Yet Scott's pieces on feminist abuse of nerds are virtually my sole exposure to the problem. This isn't surprising when you look at the data: Feminism is a minority position, even among women.

difficult. I have got a bunch of programs that filter the input I get

from social media and the news, I've blocked all of my friends who

reblog the worst stuff, and I still can't really get away from it.

In any case, Scott, how can you claim you "can't really get away from it" when you go out of your way to read and critique hostile feminists? Consider this paragraph from "Radicalizing the Romanceless."

We will now perform an ancient and traditional Slate Star Codex ritual,This doesn't sound like it's written by someone trying to minimize negative interactions with hostile feminists. At all.

where I point out something I don't like about feminism, then everyone

tells me in the comments that no feminist would ever do that and it's a

dirty rotten straw man, then I link to two thousand five hundred

examples of feminists doing exactly that, then everyone in the comments

No-True-Scotsmans me by saying that that doesn't count and those people

aren't representative of feminists, then I find two thousand five

hundred more examples of the most prominent and well-respected feminists

around saying exactly the same thing, then my commenters tell me that

they don't count either and the only true feminist lives in the

Platonic Realm and expresses herself through patterns of dewdrops on the

leaves in autumn and everything she says is unspeakably kind and

beautiful and any time I try to make a point about feminism using

examples from anyone other than her I am a dirty rotten motivated-arguer

trying to weak-man the movement for my personal gain.

MyTaken literally, you're right. Your options are, roughly, to "abandon your entire friend group," "live in a cave," or

choices are either to abandon my entire friend group, live in a cave, or

accept a leaky bubble.

"accept a leaky bubble." But that's an odd way slice your options. I freely admit that my Bubble strategy is never a 100% solution; all Bubbles leak to some degree. Can you admit that a leaky Bubble is far better than no Bubble at all?

But the purely academic/intellectual side of things isn't really the

issue here. My complaint is that feminist shaming traumatizes shy male

adolescent nerds. They're too young to have built a bubble or even

realized it's an option, and part of the way the malice works is by

convincing them that doing this makes them evil people and they're

morally obligated to take all the abuse (this strategy is very

successful if they get to people early). Other people are going to be

exposed to them whether or not I am, and I don't feel like throwing them

under the bus is the right thing to do.

Neither of us is "throwing anyone under the bus." Like you, I'm publicly offering solutions to anyone with a search engine. I just think my solution is much more effective than yours. I'm telling shy male nerds (SMNs) - including shy male adolescent nerds - how to build a Bubble to have better lives. You're telling hostile feminists to stop traumatizing SMNs. My approach will work if we get the word out to people who are suffering. Your approach will work if you persuade a subculture you deem morally reprehensible to repent.

Finally, insofar as I have non-optional interactions with people

outside my bubble - anything relating to employment, housing, or even

friends and romance when I don't have 100% ability to customize my

friends and romantic partners - the zeitgeist is going to determine

whether they treat me well or poorly... And again, even if I miraculously

manage to optimize every single life interaction to be 100% free of

people outside my bubble, other nerds are going to run into this same

problem.

You are making the best the enemy of the good. If 50% of SMNs can use my Bubble approach to reduce their suffering by 50%, it deserves high praise - not criticism that it's an incomplete solution. Why do you hold my remedy to a vastly higher standard than you hold anti-depressant drugs?

Scott does have one much better argument against my view. He thinks I'm urging Shy Male Nerds to free ride to the detriment of Shy Male Nerdkind:

Is it possible that the long-run aggregate effect of the Bubble strategy will be precisely what you say? Sure. But this is the Real World, not a homework problem on the Prisoner's Dilemma. In the Real World, waging war - hot or cold - often backfires.* You hope that if you stand up for yourself, your detractors will back down. But it often spurs them to redouble their efforts. As the author of "The Toxoplasma of Rage," I don't see how you can dispute this point. If SMNs unilaterally stop arguing with hostile feminists, I say there is a good chance that hostile feminists get bored and move on.If all the non-feminists retreat

into bubbles and leave the field to the worst feminists, then their

voices will be heard unchallenged, and then as soon as people notice I'm

a nerd they'll ignore me or hate me.[...]

And this is the purely social failure mode. Even worse is if the bad

people can get their hands on the levers of government, or affect the

people who do)What Trotsky said of war - you may not be interested in it, but it's

interested in you - seems true of politics as well, especially identity

politics.

Tell me I'm wrong, Scott.

* Trotsky learned this the hard way; if he'd remained a journalist in New York during the Russian Revolution, he wouldn't have become a mass murderer or been assassinated with

an ice pick.

(9 COMMENTS)

Diversity of the Mind, by Bryan Caplan

1. Ideological imbalance is massive.

Inbar and Lammers (2012)... set out to test Haidt's claim that there were hardly any conservatives in social psychology. They sent an email invitation to the entire SPSP [Society for Personality and Social Psychology] discussion list, from which 2923 individuals participated. Inbar & Lammers found that 85 percent of these respondents declared themselves liberal, 9 percent moderate, and only 6 percent conservative (a ratio of 14:1). Furthermore, the trend toward political homogeneity seems to be continuing: whereas 10% of faculty respondents self-identified as conservative, only 2% of graduate students and postdocs did so.2. Ideological diversity has a more scientific benefits than mere demographic diversity:

Research in organizational psychology suggest that: a) the benefits of viewpoint diversity are more consistent and pronounced than those of demographic diversity (Menz, 2012; Williams & O'Reilly, 1998); and b) the benefits of viewpoint diversity are most pronounced when organizations are pursuing open-ended exploratory goals (e.g., scientific discovery) as opposed to exploitative goals (e.g., applying well-established routines to well-defined problems; Cannella, Park & Hu, 2008).3. Ideological diversity helps defuse confirmation bias:

Seeking demographic diversity has many benefits (Crisp & Turner, 2011), including combating effects of past and present discrimination, increasing tolerance, and, in academic contexts, creating bodies of faculty who will be more demographically appealing to students from diverse demographic backgrounds. However socially beneficial such effects may be, they have little direct relation to the conduct or validity of science. Viewpoint diversity may therefore be more valuable than demographic diversity if social psychology's core goal is to produce broadly valid and generalizable conclusions. (Of course, demographic diversity can bring viewpoint diversity, but if it is viewpoint diversity that is wanted, then it may be more effective to pursue it directly.) It is the lack of political viewpoint diversity that makes social psychology vulnerable to the three risks described in the previous section. Political diversity is likely to have a variety of positive effects by reducing the impact of two familiar mechanisms that we explore below: confirmation bias and groupthink/majority consensus.

Confirmation bias can become even stronger when people confront questions that trigger moral emotions and concerns about group identity (Haidt, 2001; 2012). Further, group polarization often exacerbates extremism in echo chambers (Lamm & Myers, 1978). Indeed, people are far better at identifying the flaws in other people's evidence-gathering than in their own, especially if those other people have dissimilar beliefs (e.g., Mercier & Sperber, 2011; Sperber et al., 2010). Although such processes may be beneficial for communities whose goal is social cohesion (e.g., a religious or activist movement), they can be devastating for scientific communities by leading to widely-accepted claims that reflect the scientific community's blind spots more than they reflect justified scientific conclusions (see, e.g., the three risk points discussed previously).4. Why do liberals predominate? The paper considers all the main hypotheses. Results: Homophily and differences in interests are big parts of the story; differences in intellectual ability are not. But there is also strong evidence that (a) hostile climate and (b) conscious discrimination play big roles too. The evidence on conscious discrimination shocks even me:

Inbar and Lammers (2012) found that most social psychologists who responded to their survey were willing to explicitly state that they would discriminate against conservatives. Their survey posed the question: "If two job candidates (with equal qualifications) were to apply for an opening in your department, and you knew that one was politically quite conservative, do you think you would be inclined to vote for the more liberal one?" Of the 237 liberals, only 42 (18%) chose the lowest scale point, "not at all." In other words, 82% admitted that they would be at least a little bit prejudiced against a conservative candidate, and 43% chose the midpoint ("somewhat") or above. In contrast, the majority of moderates (67%) and conservatives (83%) chose the lowest scale point ("not at all").If you're already telling yourself, "Discrimination can't be a serious problem if people are so quick to admit their own failings," you have entered Monty Python territory.

Inbar and Lammers (2012) assessed explicit willingness to discriminate in other ways as well, all of which told the same story: when reviewing a grant, 82% of liberals admitted at least a trace of bias, and 27% chose "somewhat" or above; when reviewing a paper, 78% admitted at least a trace of bias, and 21% chose "somewhat" or above; and when inviting participants to a symposium, 56% of liberals admitted at least a trace of bias, and 15% chose "somewhat" or above. The combination of basic research demonstrating high degrees of hostility towards opposing partisans, the field studies demonstrating discrimination against research projects that are unflattering to liberals and their views, and survey results of self-reported willingness to engage in political discrimination all point to the same conclusion: political discrimination is a reality in social psychology.

The piece ends with some wonderfully quixotic proposals to fix social psychology. If anyone thinks any of these proposals will be seriously adopted, I'm ready to bet against you.

* Including personality psychology.

(9 COMMENTS)

Bryan Caplan's Blog

- Bryan Caplan's profile

- 374 followers