Bryan Caplan's Blog, page 132

December 10, 2014

The Inanity of the Welfare State, by Bryan Caplan

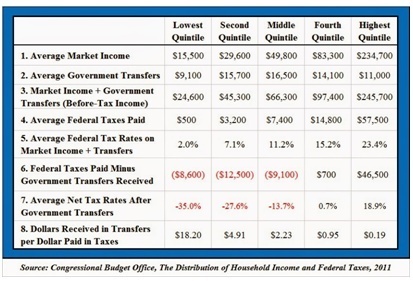

If you calmly peruse the table, however, a stranger pattern emerges - a pattern neither liberals nor conservatives will expect. Look closely. While taxes are highly progressive, transfers have an upside-down U-shape. Households in the middle quintile get the most money. The richest households actually get more money than the poorest. Think about how many times you've heard about government's great mission to "help the poor." Could there be any clearer evidence that such claims are mythology?*

If government really wanted to help the poor, it wouldn't tax everyone to fund everyone. It would raise only taxes required to help the genuinely poor, then say "mission accomplished." Relative to the status quo, that means big tax cuts and stringent means-testing. Picture a world where the lowest quintile continues to receive whatever it gets now, all other quintiles get zero, and the government refunds all the savings with tax cuts. Then ask yourself, "Why not?"

* Yes, I know that rich households have more people, but the basic pattern remains.

(16 COMMENTS)

December 9, 2014

The Moral Case for Fossil Fuels: We Owe Civilization to Fossil Fuels, by Bryan Caplan

The wise will roll their eyes at this wishful thinking. But no one exposes its sheer absurdity better than Alex Epstein in The Moral Case for Fossil Fuels . You cannot have modern civilization without abundant energy. And despite decades of government favoritism, alternative fuels have yet to deliver. As global wealth has skyrocketed, energy use has risen 80%, thanks almost entirely to increased production of fossil fuels:

FromHaven't alternative fuels played a big role, too? No.

the 1970s to the present, fossil fuels have overwhelmingly been the

fuel of choice, particularly for developing countries. In the United

States between 1980 and 2012, the consumption of oil increased 8.7

percent, the consumption of natural gas increased 28.3 percent, and the

consumption of coal increased 12.6 percent. During that time period, the

world overall increased fossil fuel usage far more than we did. Today

the world uses 39 percent more oil, 107 percent more coal, and 131

percent more natural gas than it did in 1980.

Solar and wind are aWhat's so deficient about solar and wind?

minuscule portion of world energy use. And even that is misleading

because fossil fuel energy is reliable whereas solar and wind aren't.

While energy from, say, coal is available on demand so you can keep a

refrigerator--or a respirator-- on whenever you need it, solar energy is

available only when the sun shines and the clouds cooperate, which

means it can work only if it's combined with a reliable source of

energy, such as coal, gas, nuclear, or hydro.

Why did fossil fuel

energy outcompete renewable energy-- not just for existing energy

production but for most new energy production? This trend is too

consistent across too many countries to be ignored. The answer is simply

that renewable energy couldn't meet those countries' energy needs,

though fossil fuels could. While many countries wanted solar and wind,

and in fact used a lot of their citizens ' money to prop up solar and

wind companies, no one could figure out a cost-effective, scalable

process to take sunlight and wind, which are dilute and intermittent

forms of energy, and turn them into cheap, plentiful, reliable energy.

Traditionally in discussions of solar and wind there are two problems cited: the diluteness problem and the intermittency problem. The diluteness problem is that the sun and the wind don't deliver concentrated energy, which means you need a lot of materials per unit of energy produced...But aren't some countries like Germany making solar and wind work? Not really:

Such resource requirements are a big cost problem, to be sure, and would be one even if the sun shone all the time and the wind blew all the time. But it's an even bigger problem that the sun and wind don't work that way. That's the real problem-- the intermittency problem, or more colloquially, the unreliability problem. As we saw in the Gambian hospital, it is of life and death importance that energy be reliable. There are some situations where it isn't, to be sure, and solar has a place there-- such as solar hot water heaters or swimming pool heating systems. But for just about everything we do, reliable, on-demand energy is vital--and without it, our electricity grid blacks out.

How, then, can so many say that solar or wind generates over 50 percent of Germany's energy? What they are referring to is the fact that because solar and wind are so variable, at any given moment solar can generate 50 percent of the electricity being used. It can also generate 0 percent of the electricity generated at any given moment...Of course, none of this refutes claims about fossil fuels' deadly side effects. But it does put all the kvetching in perspective. Maybe the best paragraph in the book:

As you look at the jagged and woefully insufficient bursts of electricity from solar and wind, remember this: some reliable source of energy needed to do the heavy lifting. In the case of Germany, much of that energy is coal. As Germany has paid tens of billions of dollars to subsidize solar panels and windmills, fossil fuel capacity, especially coal, has not been shut down-- it has increased...

In a given week in Germany, the world leader in solar and number three in wind, their solar panels and windmills may generate less than 5 percent of needed electricity. What happens then? Reliable sources of energy, in Germany's case coal, have to produce more electricity. For various technical reasons, this is even more inefficient than it sounds. For example, because the reliable sources have to move up and down quickly to adjust to the whims of the sunlight and wind, they become inefficient-- just like your car in stop-and-go-traffic-- which means more energy use and incidentally more emissions (including CO2). And what about when there's a particularly large amount of sunlight or wind? For an electric grid, too much electricity will cause a blackout just as too little will-- so then Germany has to shut down its coal plants and be ready to start them up again (more stop and go). In practice they often have so much excess that they have to pay other countries to take their electricity-- which requires the other countries to inefficiently decelerate their reliable power plants to accommodate the influx. This is obviously not scalable; if everyone's electrical generation was as unreliable as Germany's, there would be no one to absorb their peaks.

The only way for solar and wind to be truly useful, reliable sources of energy would be to combine them with some form of extremely inexpensive mass-storage system. No such mass-storage system exists, because storing energy in a compact space itself takes a lot of resources. Which is why, in the entire world, there is not one real or proposed independent, freestanding solar or wind power plant. All of them require backup --except that "backup" implies that solar and wind work most of the time. It's more accurate to say that solar and wind are parasites that require a host.

[A] proper reaction to a major danger from fossil fuels would be sorrow. Think about it: If the energy that runs our civilization has a tragic flaw, that is a terribly sad thing. It would be even worse, say, than if wireless technology caused brain cancer. The appropriate attitude would be gratitude toward the fossil fuel companies for what they had done for us, combined with recognition that we would have to suffer a lot in the years ahead, combined with the commitment to the best technologies that I mentioned earlier [hydro and nuclear].If anyone can turn this passage into a great cartoon, I'll be delighted to post it.

(20 COMMENTS)

December 8, 2014

The Moral Case for Fossil Fuels: The Thesis, by Bryan Caplan

When Alex Epstein's The Moral Case for Fossil Fuels arrived in my mailbox, I expected it to be bad. For two reasons:

1. In my experience, readable books about climate change usually just demagogically preach to the choir.

2. I correctly surmised that Epstein was an Objectivist, and Objectivists' policy work has long struck me as dogmatic, simplistic, and warped by anger.

Once I actually started the book, though, my negative expectations swiftly faded away. The more I read, the more Epstein's creation impressed me. My final judgment: The Moral Case for Fossil Fuels is the best book I've read all year, combining an important topic, thought-provoking evidence, and charming style. The book has too much substance to cover in a single post, so I'm going to start by explaining the thesis, then explore his major contributions in followup posts.

Epstein's book has two key claims. His first claim is descriptive: Laymen and experts alike greatly underestimate the benefits of fossil fuels and greatly overestimate their costs:

[T]he "experts" almost always focus on the risks of a technology but never the benefits-- and on top of that, those who predict the most risk get the most attention from the media and from politicians who want to "do something."What spectacular benefits? Rapid economic growth and reduction of absolute poverty in China and India, for starters. But that only scratches the surface.

But there is little to no focus on the benefits of cheap, reliable energy from fossil fuels.

This is a failure to think big picture, to consider all the benefits and all the risks. And the benefits of cheap, reliable energy to power the machines that civilization runs on are enormous. They are just as fundamental to life as food, clothing, shelter, and medical care - indeed, all of these require cheap, reliable energy. By failing to consider the benefits of fossil fuel energy, the experts didn't anticipate the spectacular benefits that energy brought about in the last thirty years.

[W]hen we look at the data, a fascinating fact emerges: As we have used more fossil fuels, our resource situation, our environment situation, and our climate situation have been improving, too.Won't global warming put an end to this bonanza? Epstein deals with the issue in detail, but the quick version is:

Here's what we know. There is a greenhouse effect. It's logarithmic. The temperature has increased very mildly and leveled off completely in recent years. The climate-prediction models are failures, especially models based on CO2 as the major climate driver, reflecting a failed attempt to sufficiently comprehend and predict an enormously complex system. But many professional organizations, scientists, and journalists have deliberately tried to manipulate us into equating the greenhouse effect with the predictions of invalid computer models based on their demonstrably faulty understanding of how CO2 actually affects climate.Epstein's second key claim is normative: Human well-being is the one fundamentally morally valuable thing. Unspoiled nature is only great insofar as mankind enjoys it:

It is only thanks to cheap, plentiful, reliable energy that we live in an environment where the water we drink and the food we eat will not make us sick and where we can cope with the often hostile climate of Mother Nature. Energy is what we need to build sturdy homes, to purify water, to produce huge amounts of fresh food, to generate heat and air-conditioning, to irrigate deserts, to dry malaria-infested swamps, to build hospitals, and to manufacture pharmaceuticals, among many other things. And those of us who enjoy exploring the rest of nature should never forget that energy is what enables us to explore to our heart's content, which preindustrial people didn't have the time, wealth, energy, or technology to do.Although Epstein doesn't really defend this moral claim, he probably doesn't need to. Green slogans notwithstanding, almost all popular and/or academically prominent moral theories place heavy weight on human well-being. And as Epstein keeps reminding us, energy is no frippery. The people of

the less-developed world - over a billion of whom still lack

electricity - have an especially desperate need for cheap energy. As long as Epstein's descriptive claims are correct, there should be an "overlapping consensus" for fossil fuels. You could even call fossil fuels the efficient, egalitarian, libertarian, utilitarian way to power the world.

P.S. To repeat, for now I'm only stating Epstein's thesis. If you want his key arguments and evidence, wait for followup posts. Or jump the queue and buy the book.

(19 COMMENTS)

December 7, 2014

An Awkward Question About Blurred Consent, by Bryan Caplan

1. False accusations are extremely rare.

2. Consent to sex is often "blurred."

Many people seem to believe both claims. But can they both be true?

If consent is frequently unclear, then whether a person was raped will often be unclear. Anytime these ambiguous circumstances lead to a rape accusation, it will be unclear whether the accusation is true or false. And if it's unclear whether a lot of accusations are false, one cannot confidently claim that false accusations are extremely rare.

Admittedly, you could claim that while blurred consent is common, the blurry cases almost never lead to rape accusations. But I haven't noticed anyone advancing this position. And aren't many activists are going out of their way to urge people to make and believe accusations even when consent is blurry?

(11 COMMENTS)

December 4, 2014

Krugman's Cursory Case Against Open Borders, by Bryan Caplan

[T]oday's immigrants are the same, in aspiration and behavior, as myKrugman's case against open borders, in contrast, is uniquely his own. How so? Most thinkers who explicitly reject open borders are convinced it would be an absolute disaster. Krugman, in contrast, opposes open borders for the mildest of reasons. Read his sentences carefully:

grandparents were -- people seeking a better life, and by and large

finding it.

That's why I enthusiastically support President Obama's new immigration initiative. It's a simple matter of human decency.

The New Deal made America a vastlyKrugman hardly sounds convinced that immigrants would have flocked to the U.S. to take advantage of the New Deal. "Justified or not" is awfully agnostic. While Krugman says the New Deal probably wouldn't have been possible without immigration restrictions, he doesn't say that immigration restrictions were required to have some version of the welfare state. Nor does he sound convinced that fear of "flocking" would have a high probability of substantially curtailing the welfare state in some form or other. "Many claims"? Name any major social program that fails to inspire "many claims" about its dangers before, during, and after its adoption.

better place, yet it probably wouldn't have been possible without the

immigration restrictions that went into effect after World War I. For

one thing, absent those restrictions, there would have been many claims,

justified or not, about people flocking to America to take advantage of

welfare programs.

Krugman continues:

Furthermore, open immigration meant that many of America's worst-paidNotice: Krugman doesn't say that exclusion of immigrants was an essential political condition for the welfare state to arise. He only says that it helped create political conditions for a stronger welfare state.

workers weren't citizens and couldn't vote. Once immigration

restrictions were in place, and immigrants already here gained

citizenship, this disenfranchised class

at the bottom shrank rapidly, helping to create the political

conditions for a stronger social safety net. And, yes, low-skill

immigration probably has some depressing effect on wages, although the available evidence suggests that the effect is quite small.

So let's sum up Krugman's case against open borders:

1. It's unclear whether immigrants would have flocked to the U.S. to take advantage of the welfare state.

2. But many would hastily assume such an effect, somewhat reducing domestic support for the welfare state.

3. Also, excluding non-voting poor immigrants somewhat altered voter demographics in the welfare state's favor.

Personally, I think that mass immigration does far more good for the truly poor than the welfare state ever has. This isn't just a weird libertarian view; Brad DeLong agrees with a few caveats:

Increased immigration is superior to strengthening the welfare state. IBut maybe Brad and I are wrong. Suppose that if we faced an either-or choice between the welfare state and open borders, we should choose the welfare state. Krugman still fails to provide any decent argument against open borders. How so? Because marginalism. Krugman claims nothing stronger than, "Open borders would have somewhat reduced the strength of the safety net." Why then is he so convinced that this marginal policy change outweighs the massive harm inflicted by making almost all immigration illegal?

just don't think it will or can happen, so I will advocate the next

best thing. From a cosmopolitan world perspective, almost all of the

costs of maldistribution come from income gaps between nations and very

little come from within-nation inequality. Development is far more

important from a world welfare perspective than social insurance within

rich countries. And immigration is a powerful tool for world

development.

This is no hyperbole. Joel Newman shows that the cost of immigration restrictions were already catastrophic by the end of Roosevelt's second term, when the U.S. turned away hundreds of thousands of people desperately struggling to escape the clutches of the Nazis. And far more would have applied if they had any hope of getting in - as millions did before World War I.

About a month ago, Krugman ridiculed lingering right-wing fear of democratic expropriation:

For the political right has always been uncomfortable with democracy. NoKrugman's right. This is a silly fear. Why? Many reasons, but the most obvious is that voters are far from selfish. Most poor voters would consider full-blown expropriation of the rich to be deeply unfair, all incentive effects aside.

matter how well conservatives do in elections, no matter how thoroughly

free-market ideology dominates discourse, there is always an

undercurrent of fear that the great unwashed will vote in left-wingers

who will tax the rich, hand out largess to the poor, and destroy the

economy.

What the history of immigration restrictions shows, however, is that decent folk should nevertheless be deeply uncomfortable with democracy. Why? Because most voters are nationalists, and nationalist voters consistently do to foreigners what low-income voters almost never do to the rich: Strip them en masse of their basic rights to work, reside, and travel. Why? For the flimsiest of reasons. Flimsy reasons like: Trapping millions of foreigners in dire poverty and bloody repression probably makes our safety net somewhat stronger.

To quote GMU econ prodigy Nathaniel Bechhofer: Paul, you're better than this.

(10 COMMENTS)

December 2, 2014

Rape Culture or Nationalist Culture?, by Bryan Caplan

The idea that the modern U.S. is a "rape culture" has always struck me as ridiculous. I've never met a person who claimed to have raped anyone. I don't know anyone who intellectually defends rape. I don't know anyone who denies that rape should be punished as a heinous crime. The way men talk definitely changes when there are zero women within earshot. But men in our culture do not become soft on rape after they retire to the parlor for cigars and brandy. True, I live in a Bubble. But I've toured American society for decades, and never detected anything remotely resembling a rape culture.

Until last Wednesday, that is.

I took my elder sons to see World War II drama Fury at the local theater. Around the middle of the film, American troops occupy a small German town. Brad Pitt and the fresh-faced newbie soldier find an apartment with two young German women. Pitt intimidates them at gunpoint, and orders the older of the women to cook him a meal. Once Pitt relaxes a little, he eyes the younger woman, then gives his new recruit a choice:

She's a good clean girl. If you don't take her into that bedroom, I will.The recruit then takes the younger woman into the bedroom while the older one stifles a protest. The camera shows the recruit and the "good clean girl" kiss, then cuts away. A little later, the she and the recruit return to the kitchen, both visibly happy.

If circumstances can ever vitiate the genuineness of consent, these plainly do. Two armed enemy soldiers burst into your apartment and start making demands. Even if the soldiers never say, "I will kill you unless you have sex with me," the women reasonably fear for their lives - and the soldiers know this full well.

Of course, Fury is only a story. Mere fiction. How could this possibly show me the rape culture in our midst? The audience reaction. During this horrific scene, hundreds of seemingly normal American men and women were laughing. Repeatedly. Loudly. The longer the scene went on, the funnier they found it.

On reflection, however, "rape culture" poorly captures the ugliness I witnessed. If the audience reaction exposed a general tolerance for rape, we should expect them to have a similarly bemused reaction if the movie showed German soldiers intimidating American women into sex. And it's obvious that the audience wouldn't have found that even slightly amusing. Instead, there'd be gasps of dismay, disgust, and anger. It's only funny when we do it to them.

What I really saw last Wednesday, then, was not a hitherto elusive rape culture. What I saw, rather, was another symptom of our ubiquitous nationalist culture. The first George Bush boiled it down to essentials:

I will never apologize for the United States -- I don't care what the facts are... I'm not an apologize-for-America kind of guy.Unlike the rape culture story, the nationalist culture story predicts that the American audience would also support - or at least not mind - mistreatment of enemy males. And that describes my fellow theater-goers to a tee. When Brad Pitt forces his recruit to kill a helpless German prisoner, I inwardly condemned Pitt as a war criminal. The people around me, however, seemed to have the reaction the screenwriters intended: "Sure, this seems cruel. But Pitt is teaching his recruit a vital lesson that could easily save American lives."

We do live in a bad culture. But it's not bad because it condones or trivializes violence against women. Few things are less acceptable to us. Our culture is bad because it condones and trivializes violence against foreigners of both genders - especially the violence of modern warfare and the violence of immigration restrictions.

"Ideals are peaceful. History is violent." That's Brad Pitt's widely quoted Fury fortune cookie. Totally wrong, of course. History is violent because many popular ideals are violent. And nationalism is one of the very worst.

P.S. Tyler Cowen told me his audience at Fury only had a few chuckles during the same scene. How about yours?

(15 COMMENTS)

December 1, 2014

Who to Fear, by Bryan Caplan

First, the racial breakdown for 2011 homicides:

Race of victim

Total

Race

of offender

White

Black

Other

Unknown

White

3,172

2,630

448

33

61

Black

2,695

193

2,447

9

46

Other race

180

45

36

99

0

Unknown race

84

36

27

3

18

The big shocking fact: The vast majority of homicides are either white-on-white (43%) or black-on-black (40%). Consistent with stereotypes, white-on-black homicide is rare - 3% of the total. But contrary to stereotypes, black-on-white homicide is also rare - 7% of the total. In fact, since blacks are roughly 13% of the U.S. population, black-on-white homicides are almost exactly as common as you'd expect if black murderers randomly selected their victims from the U.S. population. Murder is overwhelmingly intra-racial.

The results for gender look entirely different:

Sex

of offender

Sex of Victim

Total

Male

Female

Unknown

Male

4,304

3,760

450

94

Female

1,743

1,590

140

13

Unknown

84

63

3

18

Now, male-on-male (61%) and male-on-female homicides (26%) predominate. Female-on-female homicides are almost invisible - just 2% of the total. Women are over three times as likely to kill men as women.

Observations:

1. Gender patterns elegantly fit stereotypes: men commit almost all homicides, and women almost never kill each other.

2. Racial patterns, in contrast, often clash with stereotypes. Whites have little to fear from blacks, and blacks have even less to fear from whites.

3. Racial stereotypes would probably be more accurate if you focused solely on homicides between strangers. But these are rare. Our focus on such crimes probably reflects the illusion of control; since we personally control who we associate with, we imagine that our associates pose no threat.

4. Prediction: The results by nativity closely mimic the racial results. When natives think about immigrant crime, they picture immigrant-on-native crime, rather than the statistically predominant immigrant-on-immigrant crime. Testing my prediction against aggregate statistics is welcome in the comments; testing it against recent media circuses is not.

5. Yes, the government decides whether its own homicides are "justifiable." But even if you count all "justifiable homicides" by the authorities as cold-blooded murder, they won't change the overall numbers much. There are only about 400 such killings per year. Allegedly justifiable homicides by private citizens are even rarer - about 300 per year.

The overall lesson: Contrary to bipartisan fear-mongering, don't worry about getting killed by members of other races, police, or gun nuts. Turn your fear inwards. Worry about young males of your own race - because that's where the danger is.

Update: On Twitter, Alex Tabarrok and Josiah Neeley point out serious problems with the FBI's statistics on number of people killed by the authorities.

(19 COMMENTS)

November 30, 2014

The Puzzling Idealism of the Geneva Convention, by Bryan Caplan

Art. 2. Prisoners of war are in

the power of the hostile Government, but not of the individuals or formation

which captured them. They shall at all times be humanely treated and protected,

particularly against acts of violence, from insults and from public curiosity. Measures

of reprisal against them are forbidden.

But the specifics are high-minded as well. You have to leave the prisoners virtually all of their stuff:

Art. 6. All personal effects andYou can't feed enemy POWs any worse than your own troops, or cut rations to maintain control:

articles in personal use -- except arms, horses, military equipment and

military papers -- shall remain in the possession of prisoners of war, as well

as their metal helmets and gas-masks.

You can't endanger sick or wounded prisoners by transporting them (unless you invoke a seemingly huge loophole):

Art. 11. The food ration of prisoners of war shall be equivalent in quantity

and quality to that of the depot troops.

Prisoners

shall also be afforded the means of preparing for themselves such additional

articles of food as they may possess.All collective

disciplinary measures affecting food are prohibited.

Art. 25. Unless the course of

military operations demands it, sick and wounded prisoners of war shall not be

transferred if their recovery might be prejudiced by the journey.

You can't punish any prisoner offense - including escape - with anything worse than thirty days of imprisonment. If prisoners commit multiple offenses, their thirty-day sentences are served concurrently:

Art. 50. Escaped prisoners of war

who are re-captured before they have been able to rejoin their own armed forces

or to leave the territory occupied by the armed forces which captured them

shall be liable only to disciplinary punishment.

Art. 52. Belligerents shall ensure

that the competent authorities exercize the greatest leniency in considering

the question whether an offence committed by a prisoner of war should be

punished by disciplinary or by judicial measures.

Art. 54. Imprisonment is the most

severe disciplinary punishment which may be inflicted on a prisoner of war.The duration of any single punishment shall not exceed thirty days.

This maximum of thirty days shall, moreover,

not be exceeded in the event of there being several acts for which the

prisoner is answerable to discipline at the time when his case is

disposed of, whether such acts are connected or not.Where, during the course or after the

termination of a period of imprisonment, a prisoner is sentenced to a

fresh disciplinary penalty, a period of at least three days shall

intervene between each of the periods of imprisonment, if one of such

periods is of ten days or over.

Perhaps most impressively, the convention explicitly forbids legal weaseling:

III. General Observations

The conditions stated above must, in a general way, be interpreted and applied

in as broad a spirit as possible.

Taken seriously, this means that even loopholes like Article 25's "Unless the course of

military operations demands it" provide little wiggle room. If you apply prisoner protections "in as broad a spirit as possible," the obvious response to anyone who claims "the course of military operations demands the endangerment of sick and wounded prisoners" is, "Demands?! Hardly. There are plenty of other military options."

Questions:

1. Did any of the signatories of the Geneva Convention actually intend to honor it when they signed?

2. What did the signatories' military elites think about the Convention? Weren't generals around the world privately rasping, "What's our top priority? Victory - or humane treatment of our enemies?!"

3. Did the Convention's unrealistically high standards nevertheless lead to

better POW treatment than realistic standards? Or is there a kind of

Laffer Curve, where higher standards can actually lead to worse

treatment?

Please show your work.

(1 COMMENTS)

November 26, 2014

The Backward State of Behavioral Political Economy, by Bryan Caplan

I came away horribly disappointed. Not with the paper, but with the state of the literature that the authors ably summarize.I always try to begin my teaching and research in behavioral political economy with fact, not literature-driven theory. But my default model is to simply insert the weird empirics of public opinion into the standard Median Voter Model. This almost instantly implies that people in groups produce bad decisions, but I suspect Cochrane wants a richer model. John, does any of this suit you better?

I notice a lot of theory rather than fact. Stigler and company were

deeply empirical. That theory seems focused almost entirely on

individual perceptual and decision-making biases, rather than how people

in groups produce bad decisions.

[...]

Again, and again, things we ought to listen to in order to construct new theories. Please could we try to study a single fact?

Cochrane's review ends insightfully:

[T]o indulge in a little behavioral ex-post story telling of my own, aThis is exactly the situation I saw when I started my research on voter irrationality. Since I wrote The Myth of the Rational Voter , however, at least Virginia School public choicers have become more open-minded.* So I think the remaining barrier to progress is the mismatched marriage of behavioral economics and academic leftism. Alas, this long-standing marriage continues to have much higher academic status than the public choice tradition of Buchanan and Tullock.

behavioral Stigler would be hated equally by the public choice school,

which uses rational-actor economics, and by behavioral economists, who

seem, in this wide-ranging review, to remain overwhelmed by

dumb-voters-in-need-of-our-enlightened-guidance dirigisme.

* This could have something to do with the fact that I've been teaching graduate public choice at the leading bastion of Virginia School public choice for over a decade. As Kuhn taught us, get 'em young.

(0 COMMENTS)

November 25, 2014

Immigration Charity Prospect, by Bryan Caplan

Question: How hard would it be to set up a cost-effective charity to help sponsor the global poor for immigration to Argentina? Responses from GiveWell, the broader Effective Altruism community, and Argentina experts are especially welcome.

Inspired in part by Sebastian Nickel's new Libertarian Effective Altruists Facebook group.

P.S. Check out Vipul Naik's post on the prospects for immigration charity.

(0 COMMENTS)

Bryan Caplan's Blog

- Bryan Caplan's profile

- 374 followers