Bryan Caplan's Blog, page 135

October 28, 2014

Emigration and Citizenism, by Bryan Caplan

I still remember watching this interview with Mikhail Gorbachev in my high school journalism class. When Tom Brokaw asked Gorbachev about Soviet emigration restrictions, the Soviet dictator self-righteously replied:

What they're [the West] organizing is a brain drain. And of course, we're protecting ourselves. That's Number One. Then, secondly, we will never accept a condition when the people are being exhorted from outside to leave their country.This "brain drain" rationale was pervasive behind the Iron Curtain. From Alan Dowty's Closed Borders: The Contemporary Assault on Freedom of Movement (1989):

Marxist states typically place great stress on rapidTo be sure, Communist fretting about "brain drain" seems hypocritical. If they really cared about national well-being, their first logical step would be to end their brutal dictatorships. But none of this shows that the Communist arguments against free emigration were false. Allowing free emigration really could be worse for national well-being - especially if you stop counting your citizens' well-being the moment they jump ship to another country.

modernization and development, and achieving those goals depends on the

services of highly trained professionals.

But few groups feel more threatened by Marxist governments than this

one. From a position of privilege and

high reward, they are reduced to salaried servants of the state. The Marxist commitment to egalitarianism

undermines the incentive structure that professionals thrive on - and which is

usually available in neighboring lands.Thus, to prevent a brain drain, an open emigration policy

might force a state to readjust its wage structure, at a cost to other economic

priorities, not to mention ideology.

This was the conclusion, for example, of Zsuzsa Ferge, a Hungarian sociologist

who studied the economic impact of her own country's relatively liberal

emigration policies: as Hungary began to compete with the Western labor market,

it was forced to increase rewards to professionals. Representatives of Romania and Bulgaria, on

the other hand, argue that they cannot afford to match Western salaries, and

that, without a restrictive emigration policy, they "would become like Africa."

[from Dowty's personal interviews with diplomatic representatives of Romania

and Hungary]

Now suppose you subscribe to the political philosophy of citizenism: You think that governments should maximize the well-being of their citizens, with little regard for non-citizens. Is there any principled reason to reject emigration restrictions? The citizenist could say, "I favor putting citizens' interests ahead of foreigners' interests, but not some citizens' interests ahead of other citizens' interests." But immigration restrictions clearly do the latter. Some citizens greatly benefit from doing business with foreigners; immigration law still tells them, "Tough luck." In the real world, every citizenist has to make trade-offs between the welfare of different kinds of citizens.

Question: If citizenism justifies immigration restrictions, why not emigration restrictions? Or to put it more provocatively, tell me: If Gorbachev supported emigration restrictions after a sincere analysis revealed they advanced for the overall interests of the Soviet people at the expense of the high-skilled minority, is there any reason Gorbachev shouldn't be a citizenist icon for standing up to rootless cosmopolitanism?

P.S. I am well-aware that leading citizenist philosopher Steve Sailer admits exceptions to his citizenist rule. But to the best of my knowledge, he has never enumerated the main exceptions or even suggested general guidelines for making such exceptions. What we do know is that, in his eyes, even tighter immigration restrictions than already exist are morally unobjectionable. Status quo bias aside, then, why would the rights of emigrants weigh any heavier on the conscience of citizenist than the rights of immigrants?

P.P.S. If anyone knows a URL for the full Gorbachev-Brokaw interview, please post it in the comments.

(21 COMMENTS)

October 23, 2014

Compulsory Attendance IVs Reconsidered, by Bryan Caplan

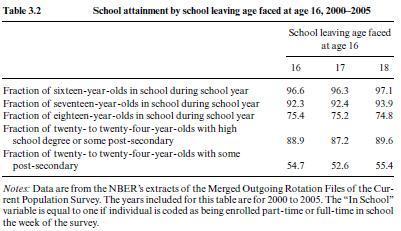

Even worse, recent compulsory attendance laws don't even predict attendance! Raw data from Philip Oreopoulos, one of the IV's biggest champions:

As a result, researchers have to make a bunch of statistical corrections before they can even begin to use compulsory attendance as an IV. Not good. IV's chief rhetorical purpose is to sequester doubts about the complexity of the world - not foster new doubts aplenty.

Until recently, though, I was under the impression that virtually every active researcher in labor economics was against me. When suddenly... the American Economic Review published Stephens and Yang's crushing critique of the entire compulsory attendance IV literature. Highlights from their "Compulsory Attendance and the Benefits of Schooling":

These state-level changes in schooling requirements are used as instrumental variables to examine the impact of increased schooling on a wide range of outcomes including wages, mortality, incarceration, and the social returns to schooling Acemoglu and Angrist 2001; Lochner and Moretti 2004; Lleras-Muney 2005; Oreopoulos 2006). Identification of these effects is achieved by exploiting variation in the timing of the law changes across states over time such that different birth cohorts within each state have different compulsory schooling requirements. Key to this identification strategy, typically implemented in specifications that include state of birth and year of birth fixed effects, is that all other changes which occur across states during this period are uncorrelated with the law changes, educational improvements, and the outcomes under investigation.Stephens and Yang go on to point out a big pile of other compatible papers I've hitherto overlooked:

[...]

In this paper, we examine the importance of the common trends assumption for estimates of the benefits of schooling when using schooling laws as instruments. In samples commonly used in the prior literature (the 1960-1980 US censuses) and across a number of outcomes including wages, occupational status, unemployment, and divorce, we find statistically significant causal effects of increased schooling when using the baseline specification which includes state of birth and year of birth effects. However, these estimates become insignificant and, in many instances, "wrong-signed" when using specifications in which the year of birth effects vary across the four US census regions of birth.

As a point of comparison, the recent empirical literature which estimates the returns to schooling using compulsory schooling law changes outside of the United States finds either small or zero returns. Since, unlike in the United States, these reforms affected a substantial share of the population, we view many of these studies as providing compelling evidence of the impact of compulsory education. Black, Devereux, and Salvanes (2005) find returns to schooling of 4 and 5 percent for men and women, respectively, due to Norwegian schooling reforms in the 1960s. Devereux and Hart (2010) find that the 1947 schooling reform in the United Kingdom yields estimated returns of 7 and 0 percent for men and women, respectively. Meghir and Palme (2005) find an overall small and insignificant return to schooling due to Swedish schooling reforms in the 1950s although they do find evidence of heterogenous returns by father's education level. Pischke and von Wachter (2008) find zero returns to schooling in Germany following a post-World War II schooling expansion and Grenet (2013) finds no returns to schooling following a 1967 education reform in France. Although the identification strategies in these studies either exploit variation across states, similar to the United States, or variation induced by a national reform, our estimates of the rate of return to schooling are comparable to the growing body of international evidence on the returns to education.If you're tempted to remain agnostic, consider this: Top economics journals almost never publish critiques. To get through the refereeing process, Stephens and Yang almost certainly had to overcome strong resistance from a series of elite referees who authored the very research they're taking down. If these meta-considerations don't win you over, nothing will.

HT: I owe my view of the quality of critiques in top econ journals to Tyler Cowen.

(0 COMMENTS)

October 22, 2014

Imagining the Proto-Blogosphere, by Bryan Caplan

Now consider the following counterfactual. Something like blogging (but no full-blown internet) came along decades or centuries earlier. How would the cream of the proto-blogosphere have reacted to...

1. Apartheid in the 1980s

2. The civil rights movement in the 1960s

3. The Great Depression

4. World War I

5. The anti-slavery movement in the 1840s, 1850s, and 1860s

Please be civil and show your work. I'll repost the best answers in a followup piece.

(5 COMMENTS)

October 21, 2014

Crime and Sheepskins, by Bryan Caplan

Education could reduce crime by enhancing students' job skills. But it could just as easily reduce crime by certifying students' job skills. If you only want to stop your kid from pursuing a life of crime, the mechanism is a red herring. If you want to stop kids in general from pursuing lives of crime, however, the mechanism is all-important. In the signaling model, to paraphrase a great meme, "When everyone has a diploma, no one does."

Empirically distinguishing human capital from signaling is notoriously tricky, but sheepskin effects - discrete benefits from crossing academic finish lines - are a strong symptom of signaling. Sheepskin effects for income are enormous. Are there comparable sheepskin effects for crime? The literature is sadly thin. But these figures from Lochner and Moretti's influential 2004 AER piece reveal big sheepskin effects of high school graduation on incarceration, with graduation year providing roughly 2/3 of the benefit.

Anyone know of other sources on sheepskin effects and crime? Google Scholar, for all its wonders, hasn't been too helpful so far.

(6 COMMENTS)

October 20, 2014

Ebola Bet Followup, by Bryan Caplan

Troy Barry:

I'll take the bet (first form), not because I have any particularTroy's payment proposal seems fair enough to me. Troy, please email me and I'll send you my address or Paypal info.

expertise or strong concern about ebola. (I do not believe closing US

borders is justified by the threat, and wouldn't even if we knew 300

resultant deaths were a certainty.) But I am sceptical of some of the

comforting assumptions of your mainstream scientists...

I acknowledge my reputation is insufficient to give you confidence in

repayment, therefore I propose to transfer $100 to you on your

acceptance. If you win the bet, you need never repay it. If you lose

the bet you transfer me $251 in January 2018. (Or suggest your own

estimate for the future value of the 2x$100 - which would be worth

hearing in itself. :)

Mike Lorenz:

Bryan - I'll take that bet. Figure out a way to determine my reliability as a counterparty.

I hope you win.

I'm happy to offer you the same terms as Troy. Is that amenable to you?

Next, the counter-offers:

I would take the bet with the proviso that it be cancelled in the event

significant travel restrictions are imposed, since that would render the

bet moot on settling the underlying policy question.

Can you propose a neutral measure of when travel restrictions become "significant," Mike?

You win $30 if by January 1, 2018 Ebola has killed less than ten

thousand people in the United States. I win $3,000 if by January 1,

2018 Ebola has killed ten thousand or more people in the United States.

To avoid bad publicity if I win pay the money to one of the top

Givewell charities. If you win I will pay you directly. I offer you

this bet for 48 hours.

I'll offer you $1000 against your $30, James. Interested?

Last, what appears to be a hypothetical bet rather than an offer:

The Ebola risk is a small risk of a high number of deaths.

Consider the bet

less than C number of Ebola deaths (x):

I pay you C-x

more than C number of deaths:

you pay me x-C

What C would you be willing to accept under these terms. My bet is

that it would be pretty high. Who would risk their life savings?

This is a wonderfully creative offer. If I were single I'd entertain it, and probably set C=1000 or so. Being married, I'm not going to make an open-ended bet.

(4 COMMENTS)October 19, 2014

Ebola Bet, by Bryan Caplan

Fortunately, this is an easy argument to put to a bet. My tentative offer: $100 says that less than 300 people will die of Ebola within the fifty United States by January 1, 2018. I'm willing to switch to "Unless the U.S. changes its Ebola-related policies, $100 says that less than 300 people will die of Ebola within the fifty United States by January 1, 2018," but then we'd have to carefully define what policy changes count.

I will make this bet with up to five individuals with sufficient reputation to make payment likely if they lose. I'm also happy to entertain alternative bets. Propose them in the comments or email me directly.

(8 COMMENTS)

Preferences in The Warriors, by Bryan Caplan

(0 COMMENTS)

October 18, 2014

Fixed Costs and Open Borders, by Bryan Caplan

Appearances withstanding, there is no contradiction between these views. As I explained a while back, fixed costs imply a straightforward consequentialist case for extremism:

Thus, even a consequentialist could consistently favor marginally expanding a program yet prefer the program's utter abolition: Marginal benefits can exceed marginal costs even though total costs exceed total benefits. On the more reasonable view that government action is only justified if its benefits heavily exceed its costs,But what if there is a fixed cost of having a carbon tax in the first place? For example, the net expected benefits could be:

-$1,000,000 + $10,000,000*p [where p=P(Al Gore is right)]

The $1,000,000 might be the overhead of the carbon tax collectors, or

the costs of every tax-payer who has to fill out a carbon tax form, or

what have you. Given this fixed cost, for p

Every micro textbook tells us that when the price of a good gets so

low that firms can't recoup their fixed costs, it makes sense to simply

close up shop - or not open in the first place. The same goes for

government programs.

the path from fixed costs to abolition is even smoother.

Are the fixed costs of borders really that high? Absolutely. Picture what a pain it would

be to erect and navigate checkpoints at every border of every U.S.

state. Imagine what even token internal restrictions would do to U.S.

commerce, travel, jobs, and housing markets. If these checkpoints were already in place, telling border guards to screen for Ebola might be reasonable. But erecting internal checkpoints to slightly reduce the risk of Ebola is crazy. And if this judgment is obviously right for internal borders, why is it obviously wrong for external borders?

(5 COMMENTS)

October 17, 2014

The Grand Budapest Hotel's Sublime Apology, by Bryan Caplan

Here's a great scene from Wes Anderson's The Grand Budapest Hotel. Gustave, manager of the Grand Budapest Hotel, has just escaped from prison after being framed for murder. Zero, an immigrant who works as the hotel's lobby boy, helped Gustave escape, but forgot to bring his employer's favorite cologne.

Gustave: I suppose this is to be expected back in... Where do you come from again?

Zero: Aq Salim al-Jabat.

Gustave: Precisely. I suppose this is to be expected back in Aq Salim al-Jabat where one's prized possessions are a stack of filthy carpets and a starving goat, and one sleeps behind a tent flap and survives on wild dates and scarabs. But it's not how I trained you. What on God's earth possessed you to leave the homeland where you obviously belong and travel unspeakable distances to become a penniless immigrant in a refined, highly-cultivated society that, quite frankly, could've gotten along very well without you?

Zero: The war.

Gustave: Say again?

Zero: Well, you see, my father was murdered and the rest of my family were executed by firing squad. Our village was burned to the ground and those who managed to survive were forced to flee. I left because of the war.

Gustave: I see. So you're, actually, really more of a refugee, in that sense? Truly. Well, I suppose I'd better take back everything I just said. What a bloody idiot I am. Pathetic fool. Goddamn, selfish bastard. This is disgraceful, and it's beneath the standards of the Grand Budapest. I apologize on behalf of the hotel. It's not your fault.

Zero: You were just upset I forgot the perfume.

Gustave: Don't make excuses for me. I owe you my life. You are my dear friend and protege and I'm very proud of you. You must know that. I'm so sorry, Zero. We're brothers.

In my dreams, this is the apology the current proponents of immigration restrictions will one day make. But I'll settle for open borders sans apology.

(19 COMMENTS)

October 16, 2014

Ebola and Open Borders, by Bryan Caplan

Some libertarians downplay the risk of Ebola, even comparing it to statistically microscopic dangers like terrorism. While I agree that Americans now overestimate their risk of Ebola infection, this plague nevertheless deserves our full attention. Throughout history, contagious disease has killed billions. Even today, contagious disease causes 16% of all global deaths. Contagious disease is at least a thousand times as deadly as terrorism. And as I have said many times, the moral presumption in favor of open borders is only that - a presumption. If open borders in the face of Ebola had awful overall consequences, and there were no cheaper and more humane remedy than immigration restrictions, some restrictions would be morally justified and I would support them. The key question, then, is: Would open borders in the face of Ebola have awful consequences?

From a long-term perspective, the effect of open borders on Ebola is anything but awful. Open borders is the greatest remedy for poverty ever discovered. Ebola is a classic disease of poverty - highly contagious in a poor society, but only slightly contagious in a rich society. In poor societies, untrained laymen unsanitarily care for the severely ill, dispose of the dead, and prepare meat. In rich societies, specialized experts perform all these tasks. And as the World Health Organization explains, unsanitary treatment of the living, the dead, and meat account for almost all Ebola contagion. If you want to eliminate serious contagious diseases like Ebola during the next few decades, open borders is probably the best way to do it.

From a short-term perspective, however, the effects of open borders on Ebola are admittedly less clear. Risks are miniscule under current U.S. conditions. The only at-risk population inside the U.S. seems to be health workers who care for Ebola patients. Even the Texas family who lived with Liberian Ebola victim Thomas Duncan look fine; they're nearly out of quarantine.

Under full open borders, however, West Africans could enter the U.S. as easily as Virginians enter Maryland. There is every reason to think that hundreds of thousands of people from Liberia, Guinea, and Sierra Leone would jump at the opportunity. And while most would be healthy, a sizable minority would be infected - possibly so many that existing U.S. health facilities would be unable to safely isolate them. Health workers' risk of catching Ebola from their patients amplifies this scarcity - for every doctor or nurse who catches Ebola, how many others will refuse to expose themselves to the disease?

Fortunately, only mild departures from full open borders are necessary to avert this scary scenario. The obvious keyhole solution: Instead of freely admitting everyone from affected countries, freely admit everyone from affected countries who provides a clean bill of health and accepts a standard 21-day quarantine.

On balance, then, horrible contagious diseases like Ebola make open borders look better, not worse. In the short-run, token restrictions are enough to prevent spreading Ebola from the Third World to the First. And in the long-run, open borders is the quickest, surest way to make diseases of poverty history.

Parting thought for all you citizenists out there: As long as the Third World remains poor, it will remain fertile breeding ground for horrible contagious diseases. Some of these diseases are likely to be far more contagious than Ebola - too contagious for the most draconian border controls to keep out. A re-run of the 1918 flu would kill two million Americans. Eradicating poverty in the Third World is therefore clearly in the interests of your countrymen, present and future. If you've got a quicker cure for Third World poverty than open borders, I'd like to hear it.

(16 COMMENTS)

Bryan Caplan's Blog

- Bryan Caplan's profile

- 374 followers