Bryan Caplan's Blog, page 138

September 14, 2014

The Logic of Gilensian Activism, by Bryan Caplan

What do our findings say about democracy in America? They certainly constitute troubling news for advocates of "populistic" democracy, who want governments to respond primarily or exclusively to the policy preferences of their citizens. In the United States, our findings indicate, the majority does not rule -- at least not in the causal sense of actually determining policy outcomes. When a majority of citizens disagrees with economic elites and/or with organized interests, they generally lose. Moreover, because of the strong status quo bias built into the U.S. political system, even when fairly large majorities of Americans favor policy change, they generally do not get it.Rather than renew debates about the rationality and selfishness of the American voter (no on both counts, but who's counting?), let's ponder a new question: What does Gilens' research imply for political activism? Gilens could urge activists to wake the sleeping majority. But American democracy's fixation on the preferences of the rich looks deeply rooted. Gilens' results hold for the entire period he examines - from Johnson to Bush II. There's no sign that matters used to be different.

The pragmatic response, then, is to tailor activism to Gilens' realities. At first, you might sigh, "It's hopeless. The rich will get their way no matter what activists do." This would be a correct inference if rich voters relentlessly sought their objective self-interest. But Gilens doesn't say that American democracy is heavily biased in favor of the interests of the rich; he says that it's heavily biased in favor of the opinions of the rich. In fact, the opinions of the rich only sporadically differ from the general population's, which is why sophisticated statistics are required to detect the rich's oversize influence.

So contrary to appearances, Gilens' analysis doesn't imply that activism is futile. The correct inference to draw, rather, is that effective activism must convert the rich. Moneybags run the show, but they're open to persuasion. Swallow your egalitarian scruples and figure out how to communicate effectively with the plutocracy. Since income and education are highly correlated, you'll want to tailor your rhetoric to both economic and educational elites. And since the young are far easily to convert than their elders, you'll want to focus on budding elites - not the whole age distribution.

The logic of Gilensian activism may sicken you, but it tantalizes me. My writings, rationalist and iconoclastic to the core, will never appeal to the man in the street or the powers-that-be. When I address young elites, however, my thoughts stand a fighting chance. Even in the best-case scenario, this gives me little influence over short-run policy; young elites are only a minority of the influential class. But persistence pays off. Anyone who can convert two successive generations of young elites can move policy mountains. See gay marriage.

Or how about immigration policy? From the standpoint of mild liberalization in 2014, my abolitionism is quixotic, if not counter-productive. The Center for Immigration Studies' Mark Krikorian isn't entirely wrong to tweet:

But Mark does miss the big picture. Namely: The principled case for open borders is already making young elites wonder if mandatory discrimination against foreigners has a moral leg to stand on. The more publicity my ideas get, the more young elites will wonder - and it's hard for them to wonder long without reaching the right answer. Who cares what these overprivileged kids think? Because if Gilens is right, their opinions will eventually decide policy.Please, @voxdotcom, do everythng in your power to make @bryan_caplan the public face of comprehnsve immigratn reform! http://t.co/47G9tu9inS

-- Mark Krikorian (@MarkSKrikorian) September 14, 2014

(5 COMMENTS)

September 13, 2014

Open Borders: My Vox Interview, by Bryan Caplan

(5 COMMENTS)

September 11, 2014

A Szaszian Take on Conformity Signaling, by Bryan Caplan

By what standards do the college psychiatrists judge [would-be drop-outs] to be immature? A psychiatrist is prone to measure maturity by the degree to which an individual adapts or adjusts to, or accepts or makes his peace with, the social milieu in which he finds himself. The psychiatrist is not prone to look with favor upon the man who suggests everyone is out of step but him, or upon the man whose reaction to society is to reject it.Notice: Keats simultaneously illustrates the facts that (a) college graduation signals conformity, because non-conformists wander off in frustration, and (b) psychiatry medicalizes a timeless clash of personality and ethics.

(1 COMMENTS)

Silent Citizenism, by Bryan Caplan

Can you imagine a politician advocating free trade on the groundsTopher remarks that "it's hard to explain America's

that, while it might hurt the politician's own country a little, it

would have enormous benefits for people living in other countries? Or

making the same argument for immigration? In the United States, critics

of military intervention tend to focus on the costs in terms of American

lives and dollars, and the "lack of a compelling national interest."

The fact that these interventions often wreak enormous havoc on the

countries we bomb and invade can seem to come in as a distant fourth in

anti-war rhetoric.I suspect this also explains much of why most people aren't more committed to fighting global poverty. People may

to believe, for example, that their donations will just get stolen by

corrupt governments, but often this sounds like an excuse. And imagine

what would happen if you went beyond praising the cost-effectiveness of

anti-malarial bed nets, and told them to direct efforts from specific local causes they support. In response, they probably wouldn't

tell you they care about geographic neighbors more than foreigners, but

you might hear a little speech about the importance of responsibility

towards your own community.

current immigration policies without assuming a lot of quiet support"

for citizenism. But he actually establishes a broader point: it's hard to explain any country's policies on any important issue without assuming a lot of quiet support for citizenism. Indeed, silent citizenism is baked into countries' very perceptions about what issues are important.

(13 COMMENTS)

September 10, 2014

First Cut, by Bryan Caplan

In most cases, though, my sense of accomplishment is short-lived. Ideological differences re-surface as soon as I advance to what I believe the next logical step: Spending cuts. To me, the concession that "Subsidizing college is a waste of money" leads straight to "Let's stop subsidizing college." My liberal fellow travelers almost invariably demur: "No, let's find a better way to spend the money."

As a rule, I try to defuse ideological deadlocks with apolitical analogies. So consider this scenario:

I argue that your toenail fungus cream doesn't work. I convince you. Which of the following reactions is more sensible: "I'm going to stop buying that stupid cream," or "Let's reallocate that money to a toenail fungus remedy that actually works"?

The former, of course. Why? Because refraining from spending money is easy - and finding effective toenail fungus remedies is hard. Once you realize you're wasting your money, you can and should stop at once. In contrast, the mere fact that you want an effective toenail fungus remedy does not give you the knowledge find such a remedy. Maybe you should look for a good way to spend your money after you cease wasting it. But stubbornly wasting money because you have no good way to spend it is crazy.

Will this apolitical analogy really dissolve ideological deadlock? Probably not, but it should. Reaching a political consensus on "a better way to spend the money" takes years, decades, or eternity. Refusing to cut wasteful spending until we agree on the right way to reallocate is therefore a great way to keep wasting money for years, decades, or eternity. When you realize a war is doing more harm than good, you should make peace - not slowly look around for a good war to fight instead. When you realize a government program is doing more harm than good, you should pull the plug, not slowly look around for a good program to fund instead. No matter what your ideology.

(12 COMMENTS)

September 9, 2014

Why Subsidize Signaling? An Open Letter to Catherine Rampell, by Bryan Caplan

I was very pleased to read your "The College Degree Has Become the New High School Degree." I'm currently writing a book defending the signaling model of education. You're clearly taking my favorite story seriously:

Note, though, that the skills required of college grads are not always ones they are taught in college.Great stuff. But it immediately reminded me of your earlier, "College is Not a Losing Investment." On the surface, your two pieces are complementary: If employers strongly prefer applicants with college degrees, college pays. But "College Is Not a Losing Investment" makes other claims that your new-found interest in signaling should make you reconsider.

Which brings me to another, potentially more troubling explanation for degree inflation: signaling.

Regardless of what you actually learn in college, graduating from a

four-year institution may broadcast that you have discipline, drive and

stick-to-it-iveness. In plenty of jobs -- such as I.T. help-desk

positions -- there is little to no difference in skill requirements

between job ads requiring a degree and those that do not, Burning Glass

found. But employers still prefer college graduates.With

Or so employers -- especially their HR departments -- seem to suspect.

college attendance more routine today it was than in the past, degrees

are becoming a common, if blunt, tool for screening job applicants. In 2013,

33.6 percent of 25- to 29-year-olds had a BA, vs. 24.7 percent in 1995.

Bachelor's degrees are probably seen less as a gold star for those who

have them than as a red flag for those who don't. If you couldn't be

bothered to get a degree in this day and age, you must be lazy,

unreliable or dumb.

First, you seem quite convinced that college (perhaps excluding the communications major) teaches valuable job skills:

One of the silver linings of the financial crisis might be that theSecond, you enthusiastically support continued (expanded?) subsidies for higher education:

lousy job market drove many people into, or back into, college to

upgrade their skills. They are reemerging more skilled and better

equipped to help expand a 21st-century economy, once it fully heals --

just as the surge in college-going enabled by the GI Bill helped grease

the economy during the postwar boom.

As for why higher ed should be subsidized: There are large, positiveI'm very skeptical of these positive spillovers; at the international level, where these effects should be plain as day, the evidence cuts the other way. But even if you're right, signaling is an offsetting effect. Consistent with the standard signaling model, your piece highlights a big negative spillover of education: The more education you get, the more other people need to avoid looking "lazy, unreliable, or dumb." Without massive subsidies for higher education, could the college degree ever have become the new high school diploma?

spillover effects from having a more educated workforce beyond the gains

that accrue to the degree-holder. Research has found that having a

higher concentration of college graduates in a local economy increases the wages of not only the college grads themselves but also those without bachelor's degrees. (Which is why it's especially shortsighted for states to cut higher education funds, which forces schools to raise tuition and price out the more marginal matriculants.)

Like Harvey Milk, I'm here to recruit you. If you have doubts about the prevalence of educational signaling, I'd love to hear them. I should warn you, however, that signaling is a gateway drug. The idea sounds harmless at first. But once you take signaling seriously, politically popular education policies - left and right - start to sound naive, if not desperate. The white elephant in the room is that there is far too much education already.

Sincerely,

Bryan

HT: Nathaniel Bechhofer

(0 COMMENTS)

September 8, 2014

Where I Dissent from Nathan Smith, by Bryan Caplan

Now for the substance. Nathan poses a thoughtful critique of my common-sense epistemology:

In his book Myth of the Rational Voter,

Caplan writes as an unabashed epistemic elitist. His thesis is that

democracy is vitiated by the "rational irrationality" of voters, who

indulge their biases (the make-work bias, the anti-market bias, the

pessimistic bias, and the anti-foreign bias) because their vote won't

affect election outcomes anyway, so they have no incentive to make

sensible choices at the ballot box, as opposed of doing whatever feels

good. That voters have these particular biases, Caplan establishes by

looking at survey data and showing how the views of ordinary people on

the economy deviate from those of economists, who presumably know

better. His assumption here is that experts know best, and that voters'

disagreements with the experts are evidence of voters' (not experts')

mistakes.But lately, Caplan seems more and more to position himself as a champion of common sense. He extols philosopher Michael Huemer for building a political philosophy on "common-sense morality," and makes a "common sense case for pacifism,"

which strikes me as merely evasive since it isn't utilitarian, but

rather seems to take a type of natural rights line that would lead to

something close to Tolstoyan pacifist-anarchism, which however he

arbitrarily stops short of, calling it "too broad." This common-sense

philosophy seems to be the platform from which Caplan attacks theories

favored among the elite, such as John Rawls' veil of ignorance. Now,

if Caplan had simply said that sometimes the common sense of ordinary

people is right, against the experts, and sometimes the experts are

right, against the common-sense of ordinary people, there would be no

inconsistency. We'd presume that neither source of knowledge is

epistemically foundational in itself, and look for other sources that

are. But as general epistemic principles, "trust the experts" and "rely

on common sense" are a bit inconsistent. If they are to think clearly

and follow the evidence where it leads, experts need to be able to

reject common-sense opinions sometimes. Conversely, if a maverick

intellectual like Caplan wants to reject this or that elite

consensus with an appeal to common sense, isn't he obliged to defer to

the opinion of the common man on other questions, too, including

questions where common sense doesn't support him?

My reply: Common-sense always comes first. But epistemic elitism is common sense. Consider these propositions:

1. When very smart people disagree with people who aren't so smart, the very smart people are probably right.

2. When people who have studied a subject for a long time disagree with people who haven't studied it, the people who have studied it for a long time are probably right.

These two claims are the heart of epistemic elitism - and both are common sense! Common sense would of course revolt against the idea that high intelligence or years of study guarantee correctness. But I've always been careful to emphasize that my epistemic elitism is merely a presumption.

How can one overcome the presumption in favor of brainy experts? The same way we unseat any common-sense view: By showing it conflicts with even more common-sensical claims. That's why a major part of my project is to show that basic economics is common sense. Not, of course, in the sense that "the common man accepts it," but that the common man would accept it if he calmed down, controlled his Social Desirability Bias, and built on what he can verify with his own two eyes. If this sounds like a tall order, I'm hardly the first person to remark that common sense is not so common.

Nathan's critique also criticizes my view that a free society rests most securely on the cultural foundation of moderate benevolence and cosmopolitan tolerance - and provides ample historical commentary to buttress his critique. On the history, I outsource my reply to Carl Shulman's extended comments on the Open Borders Action Group. But I would add that Nathan uses the term "tolerance" somewhat oddly. A typical passage:

The Roman Empire acted to defend the civic unity expressed in the

imperial cult, but its general attitude was one of tolerance, of live

and let live. It tolerated a labyrinth of religions and cults, it

tolerated prostitution, it tolerated social practices like slavery and

infanticide.

Suppose someone tries to mug you. You forcibly resist. One could that, "You're intolerant of mugging." But "intolerant" seems like the wrong English word. Similarly, to yawn in the face of slavery or infanticide is not "tolerance" in any normal sense, but "callousness." What puzzles me about Nathan's treatment is that he bundles together normal and idiosyncratic uses of the word "tolerance," and then uses his strange bundle to argue that tolerance is overrated.

(4 COMMENTS)September 4, 2014

What Every High School Junior Should Know About Going to College, by Bryan Caplan

you consider the following topic for your EconLog blog:

"What every high school junior should know before thinking of going to

college"

Suppose.....it's

the beginning of the school year in high school. Many members of the junior

class are starting to think about planning for college, i.e. do they want to go

and why, how they should start the process, what questions should they think to

be asking, etc.

Here's what I'd say...

Dear Juniors,

You've spent the last eleven years of your life in school. When you started, you were a child, and treated like a child. Now you're almost an adult, and you're finally facing some adult choices. One of the biggest: Should you stop school after you graduate from high school, or continue on to college?

Going to college definitely sounds better. Almost every authority figure in your life - educators and family alike - recommend it to each and every student. But as you may have noticed, authority figures are often untrustworthy. Indeed, they usually bend the truth whenever honesty makes them look bad. This doesn't mean you shouldn't go to college, but it is a reason to second-guess the party line, to seek out ugly facts parents and educators would rather ignore.

Fortunately, you need not seek far. Unlike most educators, I put candor above social acceptability. Skim my writings if you don't believe me. In all candor, then, here's what I have to say about going to college.

1. College is a good deal for good students, a mediocre deal for mediocre students, and a poor deal for poor students.

2. Once in a long while, a poor student morphs into good student. But

expecting any particular poor student - yourself included - to morph

into a good student is wishful thinking.

3. How do you know if you're a good, mediocre, or poor student? Look at

your past academic performance - your grades and standardized test

scores. If you're in the top 30%, you're good. If you're in the next 20%, you're mediocre. If you're in the bottom half, you're poor.

4.

This 30/20/50 breakdown is relative to all American high school students. If

your high school is academically strong, the breakdown is probably more

like 45/30/25. If your high school is academically weak, it's probably

more like 10/20/70. If this baffles you, I'm afraid

you're probably not a good student.

5. The main reason why college is a good deal for good students, a mediocre deal for mediocre students, and a poor deal for poor students: good students usually finish college, mediocre students usually don't, and poor students almost never do. And most of the payoff for college comes from finishing.

6. The secondary reason why college pays better for better students: hard majors pay better than easy majors, and better students gravitate toward harder majors.

7. One bad argument against college: "What professors teach isn't

relevant in the real world." In the labor market, degrees in the most

irrelevant subjects still open doors and raise pay. Many jobs simply

require a college degree in... whatever. The difficulty of your major matters a lot more to employers than its relevance.

8. Completion rates at two-year colleges are well below those at four-year colleges - even for students who look the same on paper. If you can't handle a four-year college, you probably can't handle a two-year college either. Two-year college is not a happy medium between four-year college and no college.

9. When you decide whether to go to college, you should consider the college experience as well as the career benefits. But the college experience is greatly overrated. A good rule of thumb: If your studies bore you in high school, they'll probably bore you in college too.

10. Don't go to college because you have no idea what career to pursue. Most recent college graduates feel the same bewilderment. In both cases, you need to dive into the labor market and try your luck.

High school juniors, I don't want to crush your dreams. But I'd rather crush your dreams than see you waste years of your lives and many thousands of dollars. When teachers and parents reassure you that "Every student is a good student," that is a flowery lie.

Suppose your 150-pound friend dreams of being a professional football player. Would a true friend urge him on? No, he'd warn his mid-weight friend that he is astronomically unlikely to succeed in football, and needs to consider more realistic careers. I'm trying to play the same role for mediocre and poor students who expect to succeed in college.

Please don't get mad at me. I am only a messenger. If you're going to get mad at anyone, get mad at all the authority figures who give you counter-productive advice to spare your feelings - and their own.

In friendship,

Bryan Caplan

Professor of Economics

George Mason University

(6 COMMENTS)

Yellen is a Good Keynesian, by Bryan Caplan

I've previously insisted that when there's high unemployment, all good Keynesians should say "Wages must fall!" I'm delighted to learn, then, that Janet Yellen is one of the good Keynesians.

The stagnation in wages despite a pickup in hiring

over the past few years has been one of the recovery's most perplexing

puzzles. But maybe the real problem isn't lack of growth. It's that

wages didn't fall enough during the recession.That idea was floated by none other than Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen during a speech on

the labor market last month during an elite central banking conference

in Jackson Hole, Wyo. She used a much fancier term -- "pent-up wage

deflation" -- but it essentially means that employers are keeping

workers' pay flat now to make up for not cutting it during the downturn.[...]

...By leaving workers' wages unchanged

during the recession, businesses were essentially overpaying their

employees. Once the recovery starts, they make up the difference the

same way -- keeping wages flat despite an improving economy.Normally, rising inflation during a recovery helps businesses reduce

costs even if wages remain unchanged. But the recovery from the Great

Recession has been characterized by particularly low inflation -- which

is likely lengthening the time firms need to keep wages flat.

I wish Yellen's words were more emphatic. But I'll take what I can get.

HT: Nathaniel Bechhofer

(5 COMMENTS)September 2, 2014

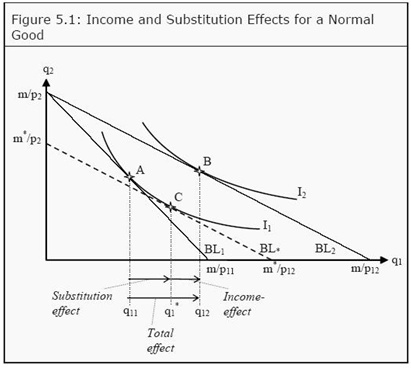

How to Teach the Income and Substitution Effects, by Bryan Caplan

When the price of q1, p1, changes there are two effects on the consumer. First, the price of q1 relative to the other products (q2, q3, . . . qn) has changed. Second, due to the change in p1, the consumer's real income changes.In case that's not instantly clear, intermediate microeconomics textbooks graphically decompose the two effects for consumers choosing between two goods:

While there's nothing incorrect about the preceding text or figure, they're unlikely to make the typical undergraduate say, "Aha! I get it." Most students readily grasp the substitution effect: If the price of x goes up, you'll naturally cut back on x. How can teachers make the income effect just as obvious?

My answer: Instead of poring over the standard two-good choice problem to decompose the substitution and income effects, teachers should start with a one-good choice problem. In this one-good setting, there is plainly no substitution effect; there is nothing to substitute to. Yet quantity demanded still clearly depends on price. If you have $50 to spend, and the price of the only good jumps from $10/unit to $25/unit, consumers reduce their consumption from 5 units to 2 units. Why? There's only one possibility: When the price goes up, the consumer's real income automatically goes down. That, students, is an unadulterated income effect.

Once students see an income effect without a substitution effect, many professors will want to show them a substitution effect without an income effect. Soon they'll be patiently explaining the income-compensated demand curve - and once again losing most of their audience. A better approach: Posit a consumer choosing between a thousand different goods, none of them a large fraction of the budget. If the price of a single good rises, the effect on the consumer's real income is negligible. But consumers will still respond to the rising price of x by buying less x.

My one-good and thousand-good problems lead straight to the meaty question: When is the income effect important, and when can it be safely ignored? With only one good, the income effect is all-important. With many goods, each a small share of the budget, the income effect is trivial. So when is the income effect important without being all-important? When at least one good is a sizable chunk of the budget, without being the whole tamale.

Housing is a great example. Most students will instantly see that a 10% rise in their rent will make them feel poorer across the board. And once students concede this point, it's fairly easy to convince them that leisure fits the mold at well. Backward-bending labor supply curves, here we come.

What about the math and the graphs? Frankly, if your students aren't going to graduate school, I'd skip both. But if that's too radical, you should still begin with my approach. Make sure your students have the underlying intuitions firmly in mind. Then show them the traditional way of formalizing those intuitions. If you must bore your students into a stupor, at least teach them some economics first!

(4 COMMENTS)

Bryan Caplan's Blog

- Bryan Caplan's profile

- 374 followers