Bryan Caplan's Blog, page 142

July 20, 2014

Endogenous Sexism Explained, by Bryan Caplan

Two lessons:

1. When a man doesn't like his wife's friends, or a women doesn't like her husband's friends, it's not surprising.

2. By itself, #1 does not imply sexism. But #1 combined with statistical naivete readily leads to sexism.

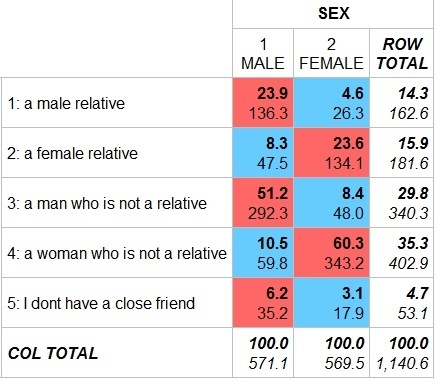

How strong should we expect this effect to be in the real world? Hard to say, but friendship is strongly segregated by gender. The General Social Survey, for example, asks about the gender of your best friend. Same-sex besties outnumber opposite-sex besties by 4:1 for men and 6:1 for women.

P.S. Don't these results imply quite a bit of unrequited best friendship? Hmm.

(4 COMMENTS)

July 17, 2014

Endogenous Sexism, by Bryan Caplan

Suppose further that no one's evaluations are gender-biased. Men have no tendency to see women as worse than they really are, and women have no tendency to see men as worse than than really are. People do however tend to get to know more people of the same sex because, say, men hunt together and women gather together.

Claim: Even in this rarefied setting, sexism will endogenously arise. Men will find the men they personally know to be better than the women they personally know. Women will find the women they personally know to be better than the men they personally know. And if people extrapolate from the people they personally know to all humanity, men will think that men are better than women, and women will think that women are better than men.

Hint: Compare the selection filter you apply to potential friends to the selection filter to apply to the romantic partners of your friends.

Please show your work.

(3 COMMENTS)

July 15, 2014

Trillion Dollar Bills on the Sidewalk: The Borjas Critique, by Bryan Caplan

[W]hat types of gains would accrue to the world's population if countries suddenly decided to remove all legal restraints to international migration and workers moved to those countries that afforded them the best economic opportunities? In contrast to the immigration surplus calculated for the receiving country's native population in the previous sections, it turns out that the "global immigration surplus" is huge and seemingly could do away with much of world poverty in one fell swoop.The critical variable is R, the First World/Third World wage ratio for equally-skilled labor:

As in the original Hamilton-Whalley (1984) study, the exercise reveals that the gains to world income are huge. If R=2, for example, world GDP would rise by $9.4 trillion, a 13.4 percent increase over the initial value of $70 trillion. If R=4, world GDP would increase by $40 trillion, almost a 60 percent increase. In fact, if R were to equal 6, which may be near the upper bound of the range of plausibility suggested by the available data, world GDP would rise by $62 trillion, a near-doubling. Note, moreover, that these gains would be accrued each year after the migration occurs, so that the present value of the gains would be astronomically high.The Borjas critique:

Even putting aside the political difficulties in enacting such a policy [open borders], this argument in favor of unrestricted international migration glosses over two conceptual obstacles.Borjas then does some back-of-the-envelope calculations and concludes:

First, the calculation assumes that people can somehow start at a specific latitude-longitude coordinate and end up at a different coordinate at zero cost... The absence of legal restrictions prohibiting the movement of people from one country to another does not circumvent the fact that it would be very costly to move billions of workers.

As noted in chapter 1, large wage differences across regions can persist for a very long time simply because many people choose not to move. In a world of income-maximizing agents, the stayers are signaling that there are substantial psychic costs to mobility, perhaps on the order of hundreds of thousands [sic] dollars per person... Kennan and Walker (2011 p.232) for instance, estimate that it costs $312,000 to move the average person from one state to another within the United States...

Although these costs seem implausibly high, moving costs must be around this order of magnitude to account for the observed fact that people do not move as much as they should given the existing regional wage differences. If moving costs were indeed in that range, it is easy to show that the huge global gains from migration become substantially smaller and may even vanish after taking moving costs into account. [emphasis original]

The "breakeven" cost of migration given in the last row of Table 7.3 is around $140,000. In short, the entire present value of the global gains is wiped out even if the costs of migration were only half of what is typically reported in existing studies.Qualitatively, Borjas' argument is entirely true. Human welfare rises by less than GDP because of material and psychic relocation costs. But quantitatively, Borjas' argument is ludicrous. Yes, he's seriously using the average valuations of Americans to estimate the marginal valuations of Third Worlders! Yet any decent econ undergrad can tell you that:

1. The marginal migrant minds moving less than average. Indeed, given the strictness of the current regime, many marginal migrants would probably take a wage cut to exit their homelands. Think of every Iraqi Shiite who can't sleep tonight because the Sunnis are coming, and every Iraqi Sunni who can't sleep tonight because the Shiites are coming.

2. Third Worlders are almost certainly willing to pay vastly less than Americans to stay in their homelands because location is a normal good. Indeed, location is probably a luxury. Does Borjas really think that most Haitians would forego $140,000 in income because they're in love with Port-au-Prince?

An excellent econ undergrad might add that:

3. Due to diaspora dynamics, psychic relocation costs endogenously fall over time. The more migrants there are, the easier it is to say adios to your country of birth. Forget the Maine, but remember Puerto Rico.

Points #1 and #2 are so basic that I reviewed all of Borjas' attendant footnotes to see if he addresses them. He grudgingly accedes to #1 in footnote 22:

Only a subset of persons in the data are actually observed to move, so that the subsample of movers may have moving costs that differ substantially from (and may be much lower than) the "average" estimates for hypothetical movers.But to the best of my knowledge, Borjas never even hints at #2 - a bizarre omission given his childhood flight from Cuba. He does however further undercut his critique in footnote 20:

It is worth noting that a disproportionately large fraction of the global gains can be accrued even if only a fraction of the potential movers migrate to the North. For example, global GDP would increase by around 17 percent when 10 percent of the potential movers move (assuming R=4).At this point, you may be asking, "Wait, didn't Borjas promise us two 'conceptual obstacles'?" He did. Sadly, his second is a throwaway objection with a single citation.

[T]he gains reported in Table 7.3 depend crucially on the assumption that the intercepts of the labor demand curves in the North and South are fixed. However, the North's demand curve lies above the South's demand curve, not simply because that is just the way things are, but because of very specific political, economic, institutional, and cultural factors that endogenously led to the development of different infrastructures in the two regions...That's all Borjas has to offer. Is he really unaware that plenty of research on the political consequences of immigration is already out there? (See Gochenour and Nowrasteh's literature review for starters) Is it really so difficult to picture major mitigating and countervailing factors? And why would one of the world's foremost immigration scholars bemoan our "unfortunate" ignorance of "the political and cultural impact of immigration on the receiving countries" instead of rolling up his sleeves and investigating the issue? Yes, we all have a limited time budget, but isn't the prospect of "doing away with much of world poverty in one fell swoop" slightly more pressing than, say, measuring the effect of migrant Soviet mathematicians on academic mathematics?

As the important work of Acemoglu and Robinson (2012) suggests, "nations fail" mainly because of differences in political and economic institutions. For immigration to generate substantial global gains, it must be the case that billions of immigrants can move to the industrialized economies without importing the "bad" institutions that led to poor economic conditions in the source countries in the first place. It seems inconceivable that the North's infrastructure would remain unchanged after the admission of billions of new workers. Unfortunately, remarkably little is known about the political and cultural impact of immigration on the receiving countries, and about how institutions in these receiving countries would adjust to the influx.

To be blunt, I suspect that Borjas prefers to remain agnostic about the political and cultural effects of immigration. That way, no matter how mighty the economic case for open borders, he'll never have to say, "Good God, how could I have been so blind? There's a whole stack of trillion dollar bills right there on the sidewalk!"

P.S. I've scheduled my first Open Borders Meet-Up at my house on August 3. All friends and fellow travelers of open borders are welcome to email me for an invitation. Pursuant to my writings, avowed immigration restrictionists may only attend with my explicit permission.

(28 COMMENTS)

July 14, 2014

Your Big Doubts About the 10,000 Hour Rule Are Well-Founded, by Bryan Caplan

What does the 10,000 Hour Rule really say? A few caveats aside, the Rule says that 10,000 hours of deliberate practice is both necessary and sufficient for world-class expertise. Listen, for example, to Gladwell talk about musical expertise.

The striking thing about Ericsson's study is that he and his colleaguesThis may seem like journalistic hyperbole, but it's quite close to the original research. Ericsson, Krampe, and Tesch-Romer:

couldn't find any "naturals," musicians who floated effortlessly to the

top while practicing a fraction of the time their peers did. Nor could

they find any "grinds," people who worked harder than everyone else, yet

just didn't have what it takes to break the top ranks. Their research

suggests that once a musician has enough ability to get into a top music

school, the thing that distinguishes one performer from another is how

hard he or she works. That's it. And what's more, the people at the very

top don't work just harder or even much harder than everyone else. They

work much, much harder.

Contrary to the popular "talent" view that asserts that differences in practice and experience cannot account for differences in expert performance, we have shown that the amount of a specific type of activity (deliberate practice) is consistently correlated with a wide range of performance including expert-level performance, when appropriate developmental differences (age) are controlled. Because of the high costs to the individuals and their environments of engaging in high levels of deliberate practice and the overlap in characteristics of deliberate practice and other known effective training situations, one can infer that high levels of deliberate practice are necessary to attain expert level performance. Our theoretical framework can also provide a sufficient account of the major facts about the nature and scarcity of exceptional performance. [emphasis mine]And:

We attribute the dramatic differences in performance between experts and amateurs-novices to similarly large differences in the recorded amounts of deliberate practice. Furthermore, we can account for stable individual differences in performance among individuals actively involved in deliberate practice with reference to the monotonic relation between accumulated amount of deliberate practice and current level of performance.Although I've found great value in Ericsson's research, his skepticism about innate talent always struck me as crazy. Yes, experts energetically hone their crafts. But everywhere I look, I see Gladwell's "naturals" - people who are good despite relatively little time investment - and "grinds" - people who are mediocre despite massive time investment. Only recently, though, did I discover a pile of research that confirms my big doubts about the 10,000 Hour Rule. Highlights of the highlights:

More than 20 years ago, researchers proposed that individual differences in performance in such domains as music, sports, and games largely reflect individual differences in amount of deliberate practice, which was defined as engagement in structured activities created specifically to improve performance in a domain. This view is a frequent topic of popular science writing--but is it supported by empirical evidence? To answer this question, we conducted a meta-analysis covering all major domains in which deliberate practice has been investigated. We found that deliberate practice explained 26% of the variance in performance for games, 21% for music, 18% for sports, 4% for education, and less than 1% for professions. We conclude that deliberate practice is important, but not as important as has been argued.The case of chess:

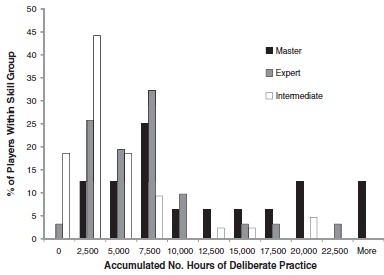

On average, deliberate practice explained 34% of the reliable variance in chess performance, leaving 66% unexplained and potentially explainable by other factors. We conclude that deliberate practice is not sufficient to account for individual differences in chess performance. The implication of this conclusion is that some people require much less deliberate practice than other people to reach an elite level of performance in chess. We illustrate this point in Fig. 2 using Gobet and Campitelli's (2007) chess sample, with the 90 players classified based on their chess ratings as "master" (≥2200, n = 16), "expert" (≥2000, n = 31), or "intermediate" (The figure:

The case of music:

On average across studies, deliberate practice explained about 30% of the reliable variance in music performance, leaving about 70% unexplained and potentially explainable by other factors. We conclude that deliberate practice is not sufficient to account for individual differences in music performance. Results of other studies provide further support for this conclusion. Simonton (1991) found a large amount of variability in the amount of time it took famous classical composers to have their first "hit," and that the interval between the first composition and the first hit correlated significantly and negatively with maximum annual output, lifetime productivity, and posthumous reputation. Composers who rose to fame quickly-the most "talented"-had the most successful careers. Furthermore, Sloboda, Davidson, Howe, and Moore (1996) noted that although students at a selective music school ("high achievers") had accumulated more "formal practice" than students who were learning an instrument at a non-music school ("pleasure players"), there were some individuals at each skill level (grade) who did "less than 20 per cent of the mean amount of practice for that grade" and others who did "over four times as much practice than average to attain a given grade" (p. 301).If deliberate practice doesn't explain everything, what does? Lots of stuff. Starting age. IQ. Personality. Specific cognitive skills, too. Consider working memory:

Ericsson and colleagues have argued that measures of working memory capacity themselves reflect acquired skills (Ericsson & Delaney, 1999; Ericsson & Kintsch, 1995), but working memory capacity and deliberate practice correlated near zero in this study (r = .003). There was also no evidence for a Deliberate Practice × Working Memory Capacity interaction, indicating that working memory capacity was no less important a predictor of performance for pianists with thousands of hours of deliberate practice than it was for beginners.Fortunately, we can salvage most of the original research behind the 10,000 Hour Rule. Instead of thinking of 10,000 hours of deliberate practice as a mandatory minimum for expertise, take it as a rule of thumb: On average, a world-class expert has to practice for about 10,000 hours to reach the top. Instead of thinking of 10,000 hours as a guarantee of expertise, adopt a pluralistic and probabilistic approach: 10,000 hours combined with lots of innate talent will usually take you to the top.

Most importantly, though, think of deliberate practice as a general theory of improvement, not a special theory of expertise! Some people learn more much easily than others. But almost anyone can improve in almost anything. How? By deliberately practicing the specific skills they wish to improve. Research on deliberate practice doesn't undermine intelligence research by showing that genius is a myth. Instead it reinforces Transfer of Learning research by showing that learning is highly specific.

HT: GMU econ prodigy Nathaniel Bechhofer

(12 COMMENTS)

Voluntary-but Bossy-Socialism, by Bryan Caplan

The more interesting question, though, is intermediate: How does voluntary-but-bossy socialism sound? Check out this 1998 WaPo profile of the Twin Oaks commune and see for yourself. Key facts: The commune members have long since learned that even people who express interest in their lifestyle rarely like it for long. (Talk about Social Desirability Bias!) Indeed, the commune can't even convince its own kids to stay.

Anyone seeking to join Twin Oaks must first live here for three weeks as a visitor, a test run for both sides. If they decide to apply, they must submit to an exhaustive interview session followed by a membership vote. After years of being at peak capacity, Twin Oaks is now trying to recover from an exodus that left a dozen vacancies, many of them from longtime members. The current population hovers near 100. In the commune's fledgling years, the average member was 23 years old with two years of college, and left in less than a year. Now the average Twin Oaker is 42, has a college degree and stays for eight years. The commune is overwhelmingly white, with roughly the same number of men andEven with this screening process, adverse selection runs amok:

women. Some 600 people have joined Twin Oaks since its inception, yet there are no second generation members. As one recruiter puts it, "Communards do not breed communards."

Families are discouraged by the lack of structured day-care or educational programs, as well as the quota limiting the number of children in the community to around 15. And while the environmental and pacifist ideals of Twin Oaks at times attract deeply passionate and committed people, recruiters like Keenan find that most who express interest fall into a far different category.Compared to involuntary socialism, voluntary-but-bossy socialism is paradise. But that's not saying much.

"This is not a standard lifestyle choice," Keenan allows. "The sort of people who tend to move here move a lot. They've not made deep emotional connections because of that . . . Someone said the visitors' program selects between loners, losers and drifters." Sooner or later, he is confident, the true loners feel crowded, the losers feel overworked and the drifters drift away. At the same time, the core of competent and capable members continues to erode. Leaving seems contagious, and the departures happen in waves. The reasons vary -- broken romances, families wanting a place of their own, disenchantment with the inevitable discovery that a commune is not one big, happy family holding hands and singing "Kumbaya" around a bonfire in the woods.

HT: Mark Steckbeck

(1 COMMENTS)

July 11, 2014

What Is Tyler Smoking?, by Bryan Caplan

Tyler's original prediction was based on a strange voting model:

When it comes to marijuana legalization,I found this story absurd because...

I believe that the "anti-" forces will muster as many parental votes as

they need to, to defeat it when they need to. The elasticity of supply

is nearly infinite at relevant margins. Legalization may appear

"close" for a long time, but in equilibrium it will not spread very

far. The "no" votes will pop up as needed.

...voter turnout isn't very flexible in general, probably isn't veryTrue, Tyler could double down on his original story. Maybe the large increase in use will galvanize parental voters, triggering re-criminalization. But I'm happy to bet against this scenario. The large increase in pot use notwithstanding, legalization will spread - not retreat.

flexible with respect to one marginal issue, and almost certainly falls

far short of "nearly infinite" elasticity. I strongly prefer the

common-sense view that when legalization appears close, it is close.

(2 COMMENTS)

July 9, 2014

Ownership for Cartoonishly Nice People , by Bryan Caplan

The noble and prolific Jason Brennan has just released Why Not Capitalism? , a short book replying to Gerald Cohen's Why Not Socialism? Outstanding work, as usual. For me, the highlight is Brennan's explanation for why even cartoonishly nice people would want to own private property. It's easy to see why cartoonishly nice people - classic Disney characters like Mickey and Minnie Mouse - would want other people to own private property. But why would the nicest people imaginable want to claim ownership on their own behalf?

It's not just that Minnie, Donald, and Willie want exclusive use-rights over objects. They also want to be able to use, give-away, sell, and in some cases, destroy these objects, as part of their pursuit of their visions of the good life. It means something for Minnie to be able to sell bows to others - that others are willing to buy from her because they like the bows rather than as a favor to her. It means something to Clarabelle that she can choose to sell her muffins or instead give them for free to a sick friend. And so on.But but but...

Some philosophers - themselves never having owned a business - might have a hard time understanding these kinds of desires. But if that philosopher can understand why one might want to write a book by oneself, rather than with co-authors or by committee, the philosopher can similarly understand why someone might want to own a factory or a farm or a store. Or, if an artist can understand why one might want to paint my oneself, rather than having each brushstroke decided by committee, or rather than having to produce each painting collectively, then the artist can similarly understand why someone might want to own a factory or a farm or a store.Furthermore:

Another closely related reason for having private property, even in utopia, has to do with the sheer aggravation of always having to ask permission. Imagine everything belonged to everybody. Now imagine everyone loves each other very much. Still, every time you go to use something, you'd have to check and see if anyone else needed or wanted to use it. ("Hey, does anyone need the laptop right now?") Or, otherwise, we'd have to develop conventions such that you knew, without asking permission, that you could use particular things at certain times. ("Oh, good, it's 6 p.m., now it's my turn to use one of the village laptops.") There's something deeply annoying about both of these scenarios, even if we love others as much as we love ourselves. We want to have a range of objects that we can count on to be free to use at will, without first having to ask permission or check with others or follow a schedule...Simply put:

People have a need to feel "at home" in the world. Most of us feel "at home" in our homes because we may unilaterally shape our homes to reflect our preferences. Our homes are governed by the principles we endorse. We do not have to deliberate in public and justify our furniture arrangements to others in society. To the extent that we have private property, we acquire the means to carve out a space for ourselves in which we can be at home.My main complaint about Why Not Capitalism? is that Brennan doesn't take Cohen to task for conflating voluntary and involuntary socialism. Cohen's book builds on a thought experiment about a socialist camping trip. The only reason the trip sounds nice - or even bearable - is that campers' socialism is voluntary. If Cohen presented a thought experiment about a camping party that inducts dissident passersby at gunpoint, almost everyone would draw an anti-socialist lesson. And when people evaluate socialism in the real world, involuntary socialism is almost always what they have in mind.

Furthermore, there's a simple way to make even Cohen's voluntary socialism unappealing: just make the campers' commune pushy and demanding. E.g., a stranger walks by the camp site minding his own business, and the voluntary socialists start preaching, "Join us! We won't force you, but you're morally obliged to join us and do whatever a majority of us say. You're selfish - selfish - unless you join. Come on, pitch in. Do it. Do it. Do it!" The awesome leftists of Bad Religion get it; why doesn't Cohen?

(6 COMMENTS)

July 8, 2014

Do Credential Scandals Support the Signaling Model?, by Bryan Caplan

Marilee Jones, the dean of admissions at the Massachusetts Institute

of Technology... admitted that she had fabricated her own educational

credentials and resigned after nearly three decades at MIT. Officials of

the institute said she did not have even an undergraduate degree."I

misrepresented my academic degrees when I first applied to MIT 28 years

ago and did not have the courage to correct my résumé when I applied

for my current job or at any time since," Jones said in a statement

posted on the institute's Web site. "I am deeply sorry for this and for

disappointing so many in the MIT community and beyond who supported me,

believed in me, and who have given me extraordinary opportunities."[...]

Jones, 55, originally from Albany, New York, had on

various occasions represented herself as having degrees from three

upstate New York institutions: Albany Medical College, Union College and

Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. In fact, she had no degrees from any

of those places, or anywhere else, MIT officials said.A spokesman

for Rensselaer said Jones had not graduated from there, though she did

attend as a part-time nonmatriculated student during the 1974-75 school

year. The other colleges said they had no record of her.

When credential scandals break, fans of the signaling model of education often run a victory lap. Should they? On the surface, credential scandals seem inconsistent with both the standard human capital model and the signaling model. Remember: Both models predict that the more-educated will be better workers than the less-educated. In the human capital model, educated workers are better because school instills job skills. In the signaling model, educated workers are better because school certifies job skills. From both perspectives, then, the fact that Marilee Jones could fake her credentials, then do a fine job for 28 years, is weird.

On deeper reflection, however, the signaling model makes credential scandals less weird than the human capital model. In the human capital model, there is no need to fake credentials; the market knows what you can do, and pays you accordingly. In the signaling model, in contrast, the market has to guess what you can do. If the initial guess is unfavorable, a qualified worker may fail to even land an interview, much less a job.

So what? Ponder a job-seeker's incentive to lie in the following two scenarios. In the first scenario, you lack both credentials and the skills those credentials normally indicate. In the second, you're a diamond in the rough - someone whose credentials understate their true skills.

Scenario #1: In the absence of deception, the market will correctly guess that you're not good enough for the job. What does lying get you? If your employer fires you as soon as he discovers your incompetence, you still get paid above your true market value for a few weeks or months. Given a typical firing-averse employer, you may get paid above your true market value until the next recession.

Scenario #2: In the absence of deception, the market will incorrectly guess that you're not good enough for the job. What does lying get you? Your big break! Your lie wins you an opportunity, and that opportunity allows you to win an employer's esteem - and start permanently earning your true market value.

The incentive to lie in Scenario #1 is plain. But in Scenario #2, the incentive to lie is overwhelming! If you're really a diamond in the rough, one well-crafted lie can change your life for the rest of your life. Or at least 28 years.

If all this is true, why do firms so often punish credential fraud with termination? "Credibility" is the obvious answer. Forgiving credential fraud committed in the past is a great way to encourage more credential fraud in the future.

But this answer dodges the more fundamental question: Why should firms detest credential fraud so much in the first place? In the human capital model, it's unclear. When you pay workers for their actual productivity, there's little need to police what workers claim about their productivity, because so little hinges on such claims.

In the signaling model, in contrast, perception is all-important, because you pay workers for their perceived productivity. Harshly punishing credential scandals sends a valuable message to all your present and future workers: "Never mess with my perceptions."

So yes, credential scandals do support the signaling model. But instead of running victory laps, fans of signaling should carefully explain why these scandals are weird, and how their preferred model makes the weirdness normal.

(2 COMMENTS)

July 7, 2014

Free Intentions, by Bryan Caplan

My favorite case: Many psychologists (and laymen) argue that consciousness is epiphenomenal. In layman's terms, unconscious urges, not conscious intentions, are the real cause of your behavior. The evidence: Some experiments where researchers manage to predict some trivial behaviors with greater than chance probability slightly before you experience a conscious intention to act.

Mele's strongest counter-evidence:

There's an important body of research on implementation intentions - intentions to do a thing at a certain place and time or in a certain situation. I'll give you some examples. In one experiment, the participants were women who wanted to do a breast self-examination during the next month. The women were divided into two groups. There was only one difference in what they were instructed to do. One group was asked to decide during the experiment on a place and time to do the examination the next month, and the other group wasn't. The first group wrote down what they decided before the experiment ended and turned the note in. Obviously, they were conscious of what they were writing down. They had conscious implementation intentions.Neat stuff. My main complaint: Mele never clearly says what I want him to say, namely:

The results were impressive. All of the women given the implementation intention instruction did complete a breast exam the next month, and all but one of them did it at basically the time and place they decided on in advance. But only 53 percent of the women from the other group performed a breast exam the following month.

In another experiment, participants were informed of the benefits of vigorous exercise. Again, there were two groups. One group was asked to decide during the experiment on a place and time for twenty minutes of exercise the next week, and the other group wasn't given this instruction. The vast majority - 91 percent - of those in the implementation intention group exercised the following week, compared to only 39 percent of the other group.

In a third experiment, the participants were recovering drug addicts who would be looking for jobs soon. All of them were supposed to write resumes by the end of the day. One group was asked in the morning to decide on a place and time later that day to carry out that task. The other group was asked to decide on a place and time to eat lunch. None of the people in the second group wrote a resume by the end of the day, but 80 percent of the first group did.

Though their methods vary, all of these free will researchers are playing a corrupt game of "Heads I win, tails I break even." They never tell us in advance what would count as evidence in favor of free will. The reason, to be blunt, is that no matter how their experiments turn out, they will never announce, "The results confirm free will." Yet Bayes' Law then automatically implies that no matter how their experiments turn out, the scientists should also never say, "The results disconfirm free will." After all, if P(hypothesis | A)>P(hypothesis), then P(hypothesis | not-A)But I suppose that's asking too much. Despite his failure to express my own position, Mele's written a fine book on a subject I considered all played out. Well done.

Upshot: The trendy "science" of free will is question-begging, probabilistically illiterate philosophy.

P.S. Just noticed Mele has a whole book on effective intentions.

(21 COMMENTS)

July 6, 2014

The Weak-Willed Do-Gooder, by Bryan Caplan

Yes. Perhaps Smith, though well-intentioned, lacks follow-through. He routinely hatches big plans, then loses interest or focus half-way through. He is, in a phrase, a weak-willed do-gooder.

What's so worrisome about weak-willed do-gooders? Simple: For many problem, half-hearted solutions have worse consequences than leaving well enough alone. This is obviously true on a purely selfish level. Investing your life savings in a business, then walking away two months later, is much worse than parking your funds in a checking account.

The same principle often holds for philanthropy. Suppose a poor soul needs a time-sensitive series of surgical procedures. Paying for step one, then skipping town, could easily be fatal for the patient. On a larger scale, imagine giving an impoverished village half the stuff it need to modernize, then suddenly walking away. Your "assistance" might lead them to drop their only source of livelihood before they have a viable alternative.

The most horrific example of weak-willed do-gooding, though, is probably "humanitarian" military intervention. The U.S. invades a country like Iraq, toppling its totalitarian government. If the U.S. were to stay until a free and prosperous society takes root, the war plausibly passes a cost-benefit test. Unconvinced? Compare North and South Korea, then try to tell yourself the Korean War was fruitless.

Nowadays, though, the U.S. rarely packages its liberations with steely resolve. Instead, modern American do-gooders spend a few years setting up a new and improved government, get bored, and walk away. The result: Not freedom and prosperity, but civil war.

What's the right lesson to draw? Hawks gravitate to the puritanical solution: "The U.S. has to become a strong-willed do-gooder. Overthrow the dictatorship, then stay without hesitation until the job is done." But this is wishful thinking. Hawks are well-aware that the modern U.S. is weak-willed. Until they figure out how to root out this vice, saying, "We'll solve our weakness of will after we win the war" is irresponsible. Why? Because given the current state of the American psyche, they should expect the policies they advocate to end badly.

You could protest, "But weakness of will is a notoriously hard vice to eliminate." That's precisely my point. If your humanitarian ambitions are going to predictably founder on the rocks of human ADHD, the true humanitarian stops before he starts. Yes, this sounds worse than "Let's do our best, and see what happens." But advocating what is better over what sounds better is the beginning of virtue.

(18 COMMENTS)

Bryan Caplan's Blog

- Bryan Caplan's profile

- 374 followers