Bryan Caplan's Blog, page 131

January 2, 2015

Shy Male Nerds and the Bubble Strategy, by Bryan Caplan

When feminists say that the market failure for young women is caused

by slut-shaming, I stop slut-shaming, and so do most other decent

people.

When men say that the market failure for young men is caused by

nerd-shaming, feminists write dozens of very popular articles called

things like "On Nerd Entitlement".

The reason that my better nature thinks that it's irrelevant whether

or not Penny's experience growing up was better or worse than

Aaronson's: when someone tells you that something you are doing is

making their life miserable, you don't lecture them about how your life

is worse, even if it's true. You STOP DOING IT.

[Quick aside: In high school, I definitely fit the SMN profile. I played Dungeons and Dragons with my male friends every Saturday night, and did not go to prom. By my second year of college, however, the problem ceased to be personally relevant. I met my wife when I was 19, married at 23, and we just celebrated our 20th anniversary. My experience may color my advice, but I leave readers to decide if that's a bug or a feature.]

My main question when reading Scott's defense of SMNs: Is this really the best way to help them out? Sure, some SMNs may feel better after reading Scott. But Scott's main intended audience seems to be the feminists who mistreat SMNs. And frankly, I can't imagine even Scott's earnest voice changing their minds. In fact, even Scott seems extremely pessimistic. He even ends his conclusion with a disclamer:

I already know that there are people reading this planning to write

responses with titles like "Entitled Blogger Says All Women Exist For

His Personal Sexual Pleasure, Also Men Are More Oppressed Than Women,

Also Nerds Are More Oppressed Than WWII Era Jews".

If helping SMNs is the goal, I think I know a better way. As usual, I recommend self-help. Specifically: SMNs should exclude hostile feminists from their Bubble. (Further background). Stop arguing with hostile feminists. Stop reading them. If you know any in real life, stop associating with them. Even if they have halfway decent reasons for berating you, you're clearly not right for each other. The best response is to amicably go your separate ways.

I realize that this approach does not solve the deeper problem of SMN loneliness. But that's no reason to amplify your unhappiness with unpleasant, fruitless social interaction with people who emotionally abuse you.

(20 COMMENTS)December 29, 2014

The Evidence of Altruism, by Bryan Caplan

ItFrom here, it is a short trip to the tragedy of the commons, kidney markets, public choice theory, and hundreds of other stories that revolve around the selfishness of man. Economists eat this stuff up.

is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker,

that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.

We address ourselves, not to their humanity but to their self-love, and

never talk to them of our own necessities but of their advantages.

Yet despite everything, it is child's play to make a room of economists howl at popular stories of self-interest. Just get the economists' attention, then deadpan, "Today I donated blood because I want to make sure there will be enough blood for me if I ever need it." Economists will climb over each other to object, "What are the odds your tiny donation will matter?" "So you're going to single-handedly keep the blood bank from running dry? Yeah right." You'll provoke similar reactions if you declare, "I joined the army to preserve my freedom," "I voted for Reagan because I couldn't afford to pay Carter's taxes" or "I give to charity in case I need charity one day."

Each of these stories appeals to self-interest, but economists almost uniformly reject them as absurd. Why? Because they ignore another beloved economic insight: the logic of collective action. When actors have a small effect on big social outcomes, and their only incentive to act is the big outcome itself, selfishness urges them to stand down, twiddle their thumbs, free ride, and yawn "Let someone else do it."

Superficial observers will see further evidence that economists can't shut up about selfishness. But on reflection, the logic of collective action is compelling evidence for the power of altruism. How so? Because actual human beings often engage in collective action despite the strong selfish case for inaction! Many people give blood without the slightest recompense. Many people voluntarily join the army when they see their country in danger, despite high risk and low wages. Many people donate to charity even though eligibility for charity has nothing to do with their donation history. If altruism is not their motive, what is?

Sure, true believers in ubiquitous selfishness can grasp at straws to protect their dogma. Perhaps people donate blood for the free cookie, join the army because they might run for office one day, or give to charity in order to make business connections. Or maybe millions of average joes are clueless enough to believe that the blood supply, the safety of the free world, and the availability of charity hinge on whatever they personally choose to do.

Anything is possible, but that doesn't mean that anything is plausible. Once you grasp the logic of collective action, basic economics strongly supports a conclusion that economists rarely advertise: Genuine altruism is all around us. Benevolence doesn't explain why bakers bake bread for paying customers, but it does explain why blood donors give blood to strangers for free.

(37 COMMENTS)

December 28, 2014

The Meaning of Tolerance, by Bryan Caplan

I'm a fan of tolerance. But Nathan Smith, one of the smartest people I've ever taught, is not. Nathan:

As for tolerance, it is subject to this paradox: that a society

cannot be tolerant without being intolerant of intolerance. To see why,

imagine a society where 95% of the population is highly tolerant both of

homosexuals, and of violence against homosexuals. Gay people in this

society can take pleasure in the knowledge that the vast majority of

their fellows look upon their lifestyles with perfect equanimity, and do

not judge or condemn them in the least. Alas, the tolerant majority

looks with the same equanimity on a small minority of self-appointed

divine avengers of sodomy and perversion. When such thugs attack a

homosexual in the street, the crowds will not sympathize, but will

reflect that, after all, who are they to judge? How can they condemn the

sincere expression of someone else's ethical beliefs? Clearly such

tolerance is hardly worth having...

American society today is intolerant of aggression; of racism; of

proposals for ethnic cleansing; of the Inquisition; of fascism and

communism; of polygamy. It harbors a propensity to lash out against

"sexism," even though this word does not, as far as I can tell, refer to

any actual coherent concept, but means whatever a person who chooses to

be offended wants it to mean at a given moment. Some parts of American

society are becoming intolerant of the idea that marriage necessarily

refers to an attachment between a man and a woman. I regard some of

these intolerances as bad, but to regard intolerance in general as bad

doesn't fundamentally make sense. You can't really even make a coherent

distinction between moral progress and intolerance of the moral evils

that moral progress overcomes...

Once I asked, "What country has ever suffered from cosmopolitan tolerance run amok?" Nathan has an answer:

...I would name the Roman Empire. There,Like most English words, "tolerance" is somewhat ambiguous. Some people use the word as Nathan does, to indicate blanket indifference or moral agnosticism. But I doubt this is the standard use of the word. Return to Nathan's hypothetical: A gang physically attacks a gay man. A bystander pulls his gun and tells them to back off. Morality aside, it seems linguistically odd to accuse the bystander of "intolerance."

the many nations of the ancient Mediterranean met and mingled,

promiscuously exchanging myths and gods and cults and light

philosophical ideas and goods and slaves. They called it the Pax Romana,

but it was a time when Roman republican liberty surrendered to the

tyranny of the Caesars, and the intellect atrophied and descended

gradually into mediocrity. Of course, the late Roman Empire wasn't

entirely tolerant as we mean the word. Thousands of Christian martyrs

died gruesome deaths merely for refusing to engage in the nominal

emperor-worship which the rest of the population indifferently and

ironically engaged in. But principled religious toleration hadn't been

invented yet. The Roman Empire acted to defend the civic unity expressed

in the imperial cult, but its general attitude was one of tolerance,

of live and let live. It tolerated a labyrinth of religions and cults,

it tolerated prostitution, it tolerated social practices like slavery

and infanticide.

If tolerance does not (normally) mean blanket indifference or moral agnosticism, what does it mean? Libertarians may be tempted to equate tolerance with not violating people's rights to person and property. But this too seems linguistically odd. Picture a homophobe who spends every day peacefully denouncing gays as disgusting and vile. Though he never commits violence or tampers with their property, he's clearly "intolerant" as we normally use the word.

What then do we normally mean by "tolerance"? As a matter of common linguistic usage, something like: Not strongly opposing what people (especially strangers) do with their own person and property. Libertarianism says, "People have a right to do what they want with their own person and property." Tolerance says, "People shouldn't get too upset about what other people do with their own person and property." Tolerance is weaker than outright approval, but it does set a cap on disapproval. Contrary to Nathan, tolerance in this sense doesn't merely allow tolerance of intolerance; it implies it! A tolerant man doesn't fret too much when X peacefully but vociferously disapproves of Y.

Note: On this definition, there is nothing intolerant about condemning,

say, nationalists for supporting immigration restrictions. A supremely tolerant person could still

say, "I'll stop attacking nationalism once nationalists become a politically impotent minority."

Whether or not I'm right about standard usage of the word "tolerance," I consider tolerance in this sense morally good - and a worthy part of the libertarian penumbra. Once you accept your duty to physically leave other people alone, it is also a good idea to mentally mind your own business. Why? Many reasons, starting with:

1. People's moral objections to how other people use their own person and property are usually greatly overstated - or simply wrong. Think about how often people sneer at the way others dress, talk, or even walk. Think about how often people twist personality clashes into battles of good versus evil. From a calm, detached point of view, most of these complaints are simply silly.

2. People's moral objections to how other people use their own person and property often conflate innocent ignorance with willful vice.

3. People's best-founded moral objections to how other people use their own person and property are usually morally superfluous. Why? Because the Real World already provides ample punishment. Consider laziness. Even from a calm, detached point of view, a life of sloth seems morally objectionable. But there's no need for you to berate the lazy - even inwardly. Life itself punishes laziness with poverty and unemployment. The same goes for drunkenness, gluttony, and so on. Such vices are, by and large, their own punishment. So even if you accept (as I do) the Rossian principle that a just world links virtue with pleasure and vice with pain, there is no need to add your harsh condemnation to balance the cosmic scales.

4. The "especially strangers" parenthetical preempts the strongest counter-examples to principled tolerance. There are obvious cases where you should strongly oppose what your spouse, children, or friends do with themselves or their stuff. But strangers? Not really.

5. Intolerance is bad for the intolerant. As Buddha never said, "Holding onto anger is like drinking poison and expecting the other person to die." The upshot is that the Real World punishes intolerance along with laziness, drunkenness, and gluttony. Perhaps this is the hidden wisdom of the truism that "Haters gonna hate."

None of these arguments are airtight. Moral arguments rarely are. Yet these arguments are enough to establish a strong moral presumption in favor of what English speakers normally mean by "tolerance." Mild disapproval of how others live their lives and spend their money is fine. But you should not dwell on the failings of strangers.

(0 COMMENTS)

December 26, 2014

The Competitive Sieve and the Burden of Proof, by Bryan Caplan

A great quote, from someone you wouldn't expect. Your guesses in the comments.

Please don't Google-and-guess!Competition is like water held in a sieve. To argue that competition does not exist

because it is absent somewhere is like saying water is not leaking because one

of the holes of the sieve is plugged.

Thus the burden of proof in the competitive-versus-noncompetitive debate

is on those who would argue lack of competition. The proponents of the noncompetitive view

have demonstrated that only a few of these holes in the competitive sieve are

plugged.

(4 COMMENTS)

December 24, 2014

Why Florida Is My Favorite State, by Bryan Caplan

In a revealed preference sense, everyone's "favorite state" almost has to be wherever he resides. If I really preferred Florida to Virginia, I'd move there, right?

To wiggle free from this tautology, you have to somehow distinguish between state's deeply-rooted features and coincidental advantages. This sounds arbitrary, but isn't hard in practice. Weather? Deeply rooted. Proximity of your best friends? Coincidental advantage. High real estate prices? Deeply rooted. Favorite restaurant five minutes away? Coincidental advantage.

Virginia has massive coincidental advantages for me: I have a dream job for life at George Mason, most of my friends live nearby, and my wife has an excellent job in the area. Since I never want to retire, I'll probably never leave Virginia. But in terms of deeply-rooted features, Florida has the best overall package in the fifty states. The top five points in Florida's favor:

1. Weather. I used to care little about the weather, but once you have kids, you really start to appreciate pleasant days for outdoor fun. And for me, Florida has the best weather in the country. Most of the state has year-round warmth and sunshine. Many observers complain about Floridian humidity, but I prefer it. While I grew up in California, I now find California painfully dry. Florida beaches are also much more inviting than California's; even in San Diego, the water is freezing.

2. Real estate. Florida has the best quality-price combination in the country. It has ubiquitous cheap housing in idyllic locations, plus tons of reasonably-priced luxury estates. Growing up in California gives you the idea that only rich people can afford to walk to the beach. If I had Mankiw money, I'd buy one of the many mansions that stretch from lake to beach, with a personal tunnel under the road, and I'd walk barefoot on the beach every night.

3. Politics. As a libertarian, I value freedom for myself and others. At the same time, though, I realize that policy differences between U.S. states are

modest. In the Mercatus Center's latest overall freedom rankings, Florida comes in 23rd - not bad, but not great. However, Florida is perfect on one measure that personally matters a lot

me: it has no income tax - and its sales tax is only 1 percentage-point higher than Virginia's. In any case, the political feature that personally matters most to me is whether I can easily forget about the existence of state government. I can do so in Virginia, and I'm confident I could do the same in Florida. I cannot do this in California, where the state government invents new problems and rams dubious solutions down your throat day after day.

4. Attitude. I prefer to be around people who are cheerful, or at least content. And as far as I can tell, Floridians are near the top. Who isn't? Californians, for starters. Where else do the checkers at the supermarket lecture you on your duty to recycle? (This actually happened to me).

5. Immigrants. I prefer to live in areas with lots of immigrants, and Florida has tons. What's so great about being around immigrants? I highly value cosmopolitan tolerance, and resent patriotic solidarity. I like being around people who know the difference between real problems and First World problems. And I like being places where nativists don't assume I share their concerns.

P.S. Mankiw also asked about my favorite Floridian locations. To live: the Gold Coast. To visit: Miami, Orlando, and Key West.

(4 COMMENTS)

December 23, 2014

Outsourced to Scott Alexander, by Bryan Caplan

1. Interpreting coefficients in discrimination regressions:

Suppose I state "Professors who identify as feminist give twice as many As to female students as they do to male students."2. The motte-and-bailey doctrine (or, as my teacher John Searle put it, "Moving from the preposterous to the platitudinous and then back to the preposterous"). Background: In a medieval castle...(This is true, by the way.)

It sounds like a big problem. So you dig through mountains of data,

and you figure out that most feminist professors tend to be in subjects

like the humanities, where twice as many students are female as male,

and so naturally twice as many of the As go to women as men. If I just

give you my best trollface and say "Yes, that's certainly the mechanism

by which the extra female As occur", you have every reason to believe

I'm deliberately causing trouble. Especially if colleges have already

vowed to stop hiring feminist professors in response to the subsequent

outrage. Especially especially if you know I am a cultural conservative

activist whose goal has always been to make colleges stop hiring

feminist professors, by hook or by crook.

If twice as many women as men take English literature classes, that's

compatible with something about gender socialization unfairly making

men feel less able to study or less enthusiastic about studying

literature. That could be considered biased or discriminatory, I guess.

But phrasing it as "feminist professors give twice as many As to women"

is calculated to produce maximal damage.

...there would be a field of desirable and economically productive land

called a bailey, and a big ugly tower in the middle called the motte.

If you were a medieval lord, you would do most of your economic activity

in the bailey and get rich. If an enemy approached, you would retreat

to the motte and rain down arrows on the enemy until they gave up and

went away. Then you would go back to the bailey, which is the place you

wanted to be all along.So the motte-and-bailey doctrine is when you make a bold,

controversial statement. Then when somebody challenges you, you claim

you were just making an obvious, uncontroversial statement, so you are

clearly right and they are silly for challenging you. Then when the

argument is over you go back to making the bold, controversial

statement.

One example:

The feminists who constantly argue about whether you can be a real

feminist or not without believing in X, Y and Z and wanting to empower

women in some very specific way, and who demand everybody support

controversial policies like affirmative action or affirmative consent

laws (bailey). Then when someone says they don't really like feminism

very much, they object "But feminism is just the belief that women are

people!" (motte) Then once the person hastily retreats and promises he definitely

didn't mean women aren't people, the feminists get back to demanding

everyone support affirmative action because feminism, or arguing about

whether you can be a feminist and wear lipstick.

Another:

Proponents of pseudoscience sometimes argue that their particular

form of quackery will cure cancer or take away your pains or heal your

crippling injuries (bailey). When confronted with evidence that it

doesn't work, they might argue that people need hope, and even a placebo

solution will often relieve stress and help people feel cared for

(motte). In fact, some have argued that quackery may be better than real

medicine for certain untreatable diseases, because neither real nor

fake medicine will help, but fake medicine tends to be more calming and

has fewer side effects. But then once you leave the quacks in peace,

they will go back to telling less knowledgeable patients that their

treatments will cure cancer.

I'd add cryonics to Scott's list.

The meta-point:

The motte and bailey doctrine sounds kind of stupid and hard-to-fall-for when you put it like that, but all fallacies sound that way when you're thinking about them.

More important, it draws its strength from people's usual failure to

debate specific propositions rather than vague clouds of ideas. If I'm

debating "does quackery cure cancer?", it might be easy to view that as a

general case of the problem of "is quackery okay?" or "should quackery

be illegal?", and from there it's easy to bring up the motte objection.

At risk of sounding smug, I don't think anyone has ever accused me of playing motte-and-bailey.

3. The definitional war on "Nice Guys":

Let's extend our analogy from above.

It was wrong of me to say I hate poor minorities. I meant I hate Poor

Minorities! Poor Minorities is a category I made up that includes only

poor minorities who complain about poverty or racism.No, wait! I can be even more charitable! A poor minority is only a Poor Minority if their compaints about poverty and racism come from a sense of entitlement.

Which I get to decide after listening to them for two seconds. And If

they don't realize that they're doing something wrong, then they're

automatically a Poor Minority.I dedicate my blog to explaining how Poor Minorities, when they're

complaining about their difficulties with poverty or asking why some

people like Paris Hilton seem to have it so easy, really just want to

steal your company's money and probably sexually molest their

co-workers. And I'm not being unfair at all! Right? Because of my new

definition! I know everyone I'm talking to can hear those Capital

Letters. And there's no chance whatsoever anyone will accidentally

misclassify any particular poor minority as a Poor Minority.

That's crazy talk! I'm sure the "make fun of Poor Minorities" community

will be diligently self-policing against that sort of thing.

Because if anyone is known for their rigorous application of epistemic

charity, it is the make-fun-of-Poor-Minorities community!I'm not even sure I can dignify this with the term "motte-and-bailey

fallacy". It is a tiny Playmobil motte on a bailey the size of Russia.

4. The best statistical guesstimates of false rape accusations you'll ever see. Just one clever section:

The rate of false rape accusations is notoriously difficult to study,

since researchers have no failsafe way of figuring out whether a given

accusation is true or not. The leading scholar in the area, David Lisak,

explains that the generally accepted methodology is to count a rape

accusation as false "if there is a clear and credible admission [of

falsehood] from the complainant, or strong evidential grounds"...[...]

Feminists make one true and important critique of these numbers -

sometimes real victims, in the depths of stress we can't even imagine,

do strange things and get their story hopelessly garbled. Or they

suddenly lose their nerve and don't want to continue the legal process

and tell the police they were making it up in order to drop the case as

quickly as possible. All of these would go down as "false allegations"

under the "victim has to admit she was lying or contradict herself"

criteria. No doubt this does happen.

But the opposite critique seems much stronger: that some false

accusers manage tell their story without contradicting themselves, and

without changing their mind and admit they were lying. We're not talking

about making it all the way through a trial - the majority of reported

rapes get quietly dropped by the police for one reason or another and

never make it that far. Although keeping your story halfway straight is

probably harder than it sounds sitting in an armchair without any cops

grilling me, it seems very easy to imagine that most false accusers manage this task, especially since they may worry that admitting their duplicity will lead to some punishment.

The research community defines false accusations as those that can be

proven false beyond a reasonable doubt, and all others as true. Yet

many - maybe most - false accusations are not provably false and so will

not be included.

5. There are good Bubbles and bad Bubbles:

[T]he problem isn't with Tumblr social justice, it's structural. EveryBy the way, Scott's intellectual output is one of the best arguments I've seen against living in a (good) Bubble. If Scott didn't routinely expose himself to painfully bad ideas, most of his best pieces would never be written.

community on Tumblr somehow gets enmeshed with the people most devoted

to making that community miserable. The tiny Tumblr rationalist

community somehow attracts, concentrates, and constantly reblogs stuff

from the even tinier Tumblr community of people who hate rationalists

and want them to be miserable (no, well-intentioned and intelligent

critics, I am not talking about you). It's like one of those rainforest

ecosystems where every variety of rare endangered nocturnal spider hosts

a parasite who has evolved for millions of years solely to parasitize

that one spider species, and the parasites host parasites who have

evolved for millions of years solely to parasitize them.

(0 COMMENTS)

December 16, 2014

The Moral Case for Fossil Fuels: Recap, by Bryan Caplan

1. The thesis.

2. We owe civilization to fossil fuels.

3. We can live with warming.

4. Refining the case.

The book's a great Christmas present, all the way down to the festive cover.

(2 COMMENTS)

December 14, 2014

The Moral Case for Fossil Fuels: Refining the Case, by Bryan Caplan

1. Epstein centers his moral case around "human life as the standard of value." This is virtually the only Objectivist jargon he uses. And when we're talking environmental ethics, it sounds reasonable. Most people, laymen and philosophers alike, think we should protect the environment primarily for the sake of humanity. Rhetorically, "human life as the standard of value" works.

Philosophically, however, it's a mess. Philosophers unfamiliar with Objectivism will assume Epstein's an old-school utilitarian, trying to maximize total human happiness. But he disavows this view:

My view of the right approach is: Respect individual rights, includingYet in the blink of an eye, Epstein seems to reintroduce "the common good" through the back door:

property rights. You have a right to your person and property, including

the air and water around you. Past a certain point, it is illegal for

anyone to affect you or your property. But-- and here's where things get

tricky-- it's not obvious what that point is. Let's look at two extremes.

One policy would be: People can pollute or endanger other individuals

at will so long as they are viewed as benefiting "the common good." This

policy, encouraged by some businesses in the nineteenth century, is

immoral. It says that some individuals should be sacrificed for the

business and its customers.

Here's another bad policy: Any amount of impact on air, water, and land should be illegal. This is simply impossible by the nature of reality-- for example, consider that perhaps our most dangerous emission, contagious disease, can often be transmitted through the air or other life forms in ways we cannot detect or prevent. At any given stage of development, some amount of potentially harmful waste cannot be prevented. For example, the man who invented fire could not protect himself or his neighbors from smoke. Should he be prohibited from using fire? Obviously not, because the right to be protected from pollution exists in a context, which is the right to the pursuit of life more broadly.Epstein might mean something like, "On the 'common good' view, pollution should be allowed as long as it benefits most people. On my view, pollution should be allowed as long as it benefits everyone." But this is an extremely stringent standard, because pollution varies widely from place to place and sensitivity to pollution varies widely from person to person. In a world of billions, there are bound to be a few asthmatics who live next to coal-fired power plants. Some are on net better off with more energy and more pollution, especially in the long-run. But others will be too sensitive (or elderly) to profit from the long-run wonders of fossil fuels. This is especially clear if NIMBYism is on the table. If we eschew arguments about "the common good," what's wrong with the position, "The government should allow moderate pollution, but none within 500 feet of me"?

My challenge for Epstein: Semantics aside, how does your view functionally diverge from the "common good" view you condemn as "immoral"? If talk about individual rights means anything, shouldn't there be noteworthy cases where you favor stricter pollution controls than utilitarians? Weaker controls?

2. Epstein powerfully argues that the total benefits of fossil fuels are enormous. Most people in our society need to hear this. But this doesn't imply that the marginal benefits of fossil fuels are enormous, or even positive. This is textbook environmental economics: Most human beings blithely pollute even when the personal benefit of extra pollution is small and the cost to strangers of extra pollution is high. The textbook solution, of course, is to raise the price of pollution. In the long-run, this spurs industry to search for cleaner technologies. In the short-run, though, it deliberately does something rhetorically uncomfortable for Epstein: discourage energy consumption.

I'm sure Epstein understands marginal thinking. But the word "marginal" appears but once in his book. Instead, he talks repeatedly about "minimizing" environmental harms. A typical passage:

[D]evelopment and the fossil fuel energy that powers it carries risks and creates by-products, such as coal smog, that we need to understand and minimize, but these need to be viewed in the context of fossil fuels' overall benefits, including their environmental benefits. And it turns out that those benefits far, far outweigh the negatives-- and technology is getting ever better at minimizing and neutralizing those risks.This is sloppy thinking. There's only one way to "minimize" the negative effects of coal use: Use zero coal. To avoid this implication, you have to minimize negative effects subject to some another constraint, such as maintaining 3% economic growth. But this formulation has a rhetorically unwelcome effect for Epstein: it highlights the trade-off between pollution abatement and other goods. Epstein is right, of course, to point out all the ways that technology powered by fossil fuels helps clean the environment. But we nevertheless face trade-offs between pollution abatement and other goods on a daily basis.

3. When societies get rich enough, they use technology and laws to clean up the environment. Epstein is all for this. A typical passage:

Nineteenth-century coal technology is justifiably illegal today. The hazardous smoke that would be generated is now preventable by far more advanced, cleaner coal-burning technologies. But in the 1800s, it was and should have been perfectly legal to burn coal this way-- because the alternative was death by cold or starvation or wretched poverty.While this technology-and-law approach sounds very sensible, it pales in comparison to the wisdom of textbook environmental economics. The essence of the approach: Neither tolerate nor ban pollution. Instead, put a price on it! This simultaneously (a) discourages pollution at the margin and (b) encourages anti-pollution innovation. It also raises revenue, allowing government to reduce taxes on work and savings. Yes, this approach has some moral and practical problems. But it's still the story to beat - and Epstein doesn't address it.

The good news is the Epstein is both young and young at heart. He has ample time and energy to refine the moral case for fossil fuels - and I'm optimistic that he will.

P.S. I'm leaving for family vacation in my favorite state, Florida, today. Happy holidays to all! And if you happen to spot me in southern Florida, please say hi.

(4 COMMENTS)

The Man of One Study, by Bryan Caplan

So here's why you should beware the man of one study.

If you go to your better class of alternative medicine websites, they

don't tell you "Studies are a logocentric phallocentric tool of Western

medicine and the Big Pharma conspiracy."

They tell you "medical science has proved that this drug is terrible,

but ignorant doctors are pushing it on you anyway. Look, here's a study

by a reputable institution proving that the drug is not only

ineffective, but harmful."

And the study will exist, and the authors will be prestigious

scientists, and it will probably be about as rigorous and well-done as

any other study.

And then a lot of people raised on the idea that some things have Evidence and other things have No Evidence think holy s**t, they're right!

On the other hand, your doctor isn't going to a sketchy alternative

medicine website. She's examining the entire literature and extracting

careful and well-informed conclusions from...

Haha, just kidding. She's going to a luncheon at a really nice

restaurant sponsored by a pharmaceutical company, which assures her that

they would never take advantage of such an opportunity to shill

their drug, they just want to raise awareness of the latest study. And

the latest study shows that their drug is great! Super great! And your

doctor nods along, because the authors of the study are prestigious

scientists, and it's about as rigorous and well-done as any other study.

But obviously the pharmaceutical company has selected one of the studies from the "very good" end of the bell curve.

Read the whole thing, including the stuff about the minimum wage.

(1 COMMENTS)December 11, 2014

The Moral Case for Fossil Fuels: We Can Live With Warming, by Bryan Caplan

[T]hose who dispute catastrophic global warming are accused of denying the greenhouse effect and global warming. I experienced this in 2013 when I woke up to find myself named to Rolling Stone's Top 10 list of "Global Warming's Denier Elite" --in which they cited three articles of mine, each of which explained that CO2 has a warming effect!How can anyone believe in anthropogenic global warming yet continue to enthuse over fossil fuels? It's a question of magnitudes, of course. Massive warming is deadly; modest warming is fine. Epstein thinks the magnitude of warming has been - and will remain - modest. Which brings us to the obvious question: Why should anyone go with his judgment, rather than the scientific consensus?

There was a time, Epstein admits, that he didn't take this challenge seriously.

But there was so much going on in discussions of global warming , I didn't know how to decide where the evidence lay. I would hear different sides say different things about sea levels, polar bears, wildfires, droughts, hurricanes, temperature increases, what was and wasn't caused by global warming, and on and on.Most us, myself included, are in the same epistemic boat. I'm not qualified to evaluate Epstein's main claims about the magnitude of global warming. But he expresses his main claims so clearly that experts shouldn't find it hard to confirm or deny them. Two claims in particular stand out.

With such a mess to work with, I - like most, I think - tended to side with the scientists or commentators whose conclusions were more congenial to me. I will admit to reiterating the arguments of skeptics of of catastrophic global warming with the lack of rigor I think is extremely common among believers. But I didn't do this for long. I acknowledged that I didn't really know what to think, and the idea that we might be making the Earth fundamentally uninhabitable scared me.

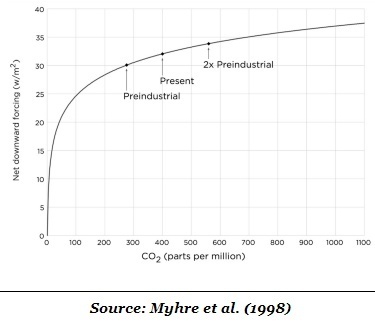

Claim #1: While hard experimental evidence confirms a greenhouse effect, this effect is logarithmic; increasing CO2 warms at a decreasing rate:

While I've met thousands of students who think the greenhouse effect of CO2 is a mortal threat, I can't think of ten who could tell me what kind of effect it is. Even "experts" often don't know, particularly those of us who focus on the human-impact side of things. One internationally renowned scholar I spoke to recently was telling me about how disastrous the greenhouse effect was , and I asked her what kind of function it was. She didn't know. What I told her didn't give her pause, but I think it should have.Figure 4.1: The Decelerating, Logarithmic Greenhouse Effect

As the following illustration shows, the greenhouse effect of CO2 is an extreme diminishing effect--a logarithmically decreasing effect. This is how the function looks when measured in a laboratory.

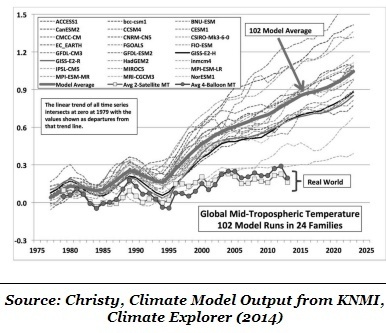

Claim #2: Complex interactions between this logarithmic greenhouse effect and other factors could generate a lot more warming, but this is not based on hard experimental evidence. The only way to judge these more complex climate models is against observational data. What we've learned over the past few decades is that these models systematically overstate warming:

Here's the summary of what has actually happened-- a summary that nearly every climate scientist would have to agree with. Since the industrial revolution, we've increased CO2 in the atmosphere from .03 percent to .04 percent, and temperatures have gone up less than a degree Celsius, a rate of increase that has occurred at many points in history. Few deny that during the last fifteen-plus years, the time of record and accelerating emissions, there has been little to no warming-- and the models failed to predict that. By contrast, if one assumed that CO2 in the atmosphere had no major positive feedbacks, and just warmed the atmosphere in accordance with the greenhouse effect, this mild warming is pretty much what one would get.Which brings us to the single most striking figure in the whole book.

Thus every prediction of drastic future consequences is based on speculative models that have failed to predict the climate trend so far and that speculate a radically different trend than what has actually happened in the last thirty to eighty years of emitting substantial amounts of CO2.

Figure 4.3: Climate Prediction Models That Can't Predict Climate

[larger version]

My question for experts: Is there anything seriously wrong with this figure? In particular, is it really true that virtually every major climate model overpredicts global temperature? I'm genuinely curious, but I insist on a straight answer.

(5 COMMENTS)

Bryan Caplan's Blog

- Bryan Caplan's profile

- 374 followers