Stephen Hayes's Blog, page 38

August 3, 2016

Of whom I am first

There are two kinds of people in the world: those who believe there are two kinds of people and those who don’t.

The two kinds of people are those who believe that the world can be divided into good guys (us) and bad guys (them), and those who believe that we ourselves are part of the problem.

A few days ago Jim Forest, of the Orthodox Peace Fellowship, drew my attention to a review of a book on the poet Wystan Hugh Auden which put this very well indeed — The Secret Auden by Edward Mendelson | The New York Review of Books:

By refusing to claim moral or personal authority, Auden placed himself firmly on one side of an argument that pervades the modern intellectual climate but is seldom explicitly stated, an argument about the nature of evil and those who commit it.

On one side are those who, like Auden, sense the furies hidden in themselves, evils they hope never to unleash, but which, they sometimes perceive, add force to their ordinary angers and resentments, especially those angers they prefer to think are righteous. On the other side are those who can say of themselves without irony, “I am a good person,” who perceive great evils only in other, evil people whose motives and actions are entirely different from their own. This view has dangerous consequences when a party or nation, having assured itself of its inherent goodness, assumes its actions are therefore justified, even when, in the eyes of everyone else, they seem murderous and oppressive.

This is something that Orthodox Christians are, or ought to be reminded of every time they receive the Holy Communion, with the prayer that begins “I believe O Lord and I confess that Thou art truly the Christ, the Son of the living God, who camest into the world to save sinners, of whom I am first.”

This is all too easily forgotten, sooner or later after receiving the holy communion, when we revert to our usual habit of perceiving ourselves as more righteous and less sinful than other people. This habit becomes even more easy to slip into in times or war, or even elections. Right now we are preparing for local government elections in South Africa, and the rhetoric is hotting up, though we don’t seem to be a patch on the Americans, whose rhetoric seems to be even more extreme and vituperative (did you see what I just did there?)

This is all too easily forgotten, sooner or later after receiving the holy communion, when we revert to our usual habit of perceiving ourselves as more righteous and less sinful than other people. This habit becomes even more easy to slip into in times or war, or even elections. Right now we are preparing for local government elections in South Africa, and the rhetoric is hotting up, though we don’t seem to be a patch on the Americans, whose rhetoric seems to be even more extreme and vituperative (did you see what I just did there?)

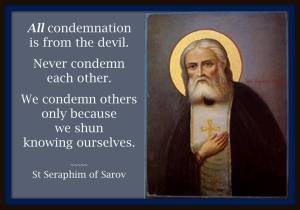

Someone asked (of that saying of St Seraphim of Sarov) “What does he mean by condemn? Does that mean giving constructive criticism too?”

When St Seraphim said “All condemnation is from the devil”, he may have been referring to Revelation 12:9-12 “And the great dragon was cast out, that old serpent, called the Devil, and Satan, which deceiveth the whole world” ( καὶ ἐβλήθη ὁ δράκων ὁ μέγας, ὁ ὄφις ὁ ἀρχαῖος, ὁ καλούμενος Διάβολος καὶ ὁ Σατανᾶς, ὁ πλανῶν τὴν οἰκουμένην ὅλην) . The point here is that both the Greek word diavolos (from which the English word “devil” is derived) and the Hebrew word Satan mean “adversary” or “accuser”, something like a prosecutor in a law court, and that is clear in v10 “the accuser of our brethren is cast down, which accused them before our God day and night” (ὅτι ἐβλήθη ὁ κατήγορος τῶν ἀδελφῶν ἡμῶν, ὁ κατηγορῶν αὐτῶν ἐνώπιον τοῦ Θεοῦ ἡμῶν ). The categoriser of our brethren to thrown out, the one who categorised (or pigeonholed) them before God (cf Zechariah 3). The most satanic activity we can ever engage in is the making of accusations.

This is all summed up rather tritely in a saying that has almost become a cliche: Hate the sin, but love the sinner.

One can criticise constructively (or even destructively, if necessary) what a person does, but not what that person is. Judging by what a person is is what is called an ad hominem argument — this person is a bad person, therefore what this person says must be wrong. And so in politics, one may (and sometimes should) criticise the policies of a politician but to condemn the person crosses the line, and puts us on the side of the devil, as St Seraphim points out.

And “Hate the sin but love the sinner” also becomes monstrously hypocritical without the “of whom I am first”. Is Jacob Zuma a sinner? So am I. Is Hillary Clinton a sinner? So am I. Is Donald Trump a sinner? So am I. Is Poroshenko a sinner? So am I. Is Putin a sinner? So am I. Was Tony Blair a sinner? So am I. Was B.J. Vorster a sinner? So am I. Was Adolf Hitler a sinner? So am I.

When, over the next few months, you see (as you surely will) pictures of any of these political leaders, or others, on Facebook and other social media, with their ugliest possible pictures, and denunciations of their policies, then ask yourself whether those are really their policies, or policies falsely imputed to them by their political opponents or the media. And judge whether the policies are good or bad according to conscience. But if it merely attacks the person rather than the policy, then do not like, do not share, just say a prayer and pass on.

What Auden writes against is the tendency to put wicked politicians (or other kinds of sinners) in a separate category that doesn’t include us. They are mad, insane, inhuman. And it is this putting people in a separate inhuman category that was so characteristic of the devil — the categoriser of our brethren has been thrown out (Revelation 12:10) . When we say that someone is a waste of space, a waste of oxygen, a worthless human being, we blaspheme the God who made them and us.

G.K. Chesterton, a contemporary of W.H. Auden, wrote:

The whole case for Christianity is that a man who is dependent upon the luxuries of this life is a corrupt man, spiritually corrupt, politically corrupt, financially corrupt. There is one thing that Christ and all the Christian saints have said with a sort of savage monotony. They have said simply that to be rich is to be in peculiar danger of moral wreck. It is not demonstrably un-Christian to kill the rich as violators of definable justice. It is not demonstrably un-Christian to crown the rich as convenient rulers of society. It is not certainly un-Christian to rebel against the rich or to submit to the rich. But it is quite certainly un-Christian to trust the rich, to regard the rich as more morally safe than the poor. A Christian may consistently say, “I respect that man’s rank, although he takes bribes.” But a Christian cannot say, as all modern men are saying at lunch and breakfast, “a man of that rank would not take bribes.” For it is a part of Christian dogma that any man in any rank may take bribes. It is a part of Christian dogma; it also happens by a curious coincidence that it is a part of obvious human history. When people say that a man “in that position” would be incorruptible, there is no need to bring

Christianity into the discussion. Was Lord Bacon a bootblack? Was the Duke of Marlborough a crossing sweeper? In the best Utopia, I must be prepared for the moral fall of any man in any position at any moment; especially for my fall from my position at this moment.

Can I trust Jacob Zuma and his cronies the Guptas? No. Can I trust Donald Trump? No. Can I trust Hillary Clinton? No. Can I trust myself? No. The last sentence in the quote from Chesterton is the most important.

A friend in college introduced me to W.H. Auden’s poem Vespers, in which he expressed the sentiment described in the quotation with which I began this article:

Was it (as it must look to any god of cross-roads) simply a fortuitous intersection of life-paths, loyal to different fibs or also a rendezvous between accomplices who, in spite of themselves, cannot resist meeting to remind the other (do both, at bottom, desire truth?) of that half of their secret which he would most like to forget…

You can see the whole poem (Horae Cononicae) here, or even hear Auden himself reading it, here.

August 2, 2016

The only daughter (book review)

The Only Daughter by Jessica Anderson

The Only Daughter by Jessica Anderson

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

Four years ago I read an Australian novel about families of Greek immigrants in Melbourne, The Slap. This one is about established Australian families a generation earlier, in Sydney. In spite of the differences of time and style, both books seemed intensely suburban. My wife and I kept comparing them, and we both thought that this one was rather better written than The slap (review here) .

Jack and Greta Cornock have no children of their own, but each of them has 30-something children from previous marriages, some single, some married, some divorced. Jack’s daughter Sylvia Foley (divorced), who has been overseas in Europe for 20 years, returns for a brief visit to discover that her father has had a stroke, and her step-siblings are concerned about what he has left to their mother in his will. Like The Slap it goes into great detail about the minutiae of suburban life, and the concerns of middle-class suburban people, until one discovers that the older generation had a much harder time of it in their youth.

The book has a genealogical table in the front to help one to picture the complex relationship s between the main characters, and I found myself wishing that it also had a map of Sydney, so that one could picture the relationships between the places described, sometimes in great detail.. In spite of this, some details were rather fuzzy and blurred. In The Slap one was not told the ages of several of the children, so it was difficult to picture them. in The only daughter the ages of the children are given, but the makes and models of cars the characters drive around in are not. Perhaps that’s a difference between South African and Australian culture, or perhaps it is a difference between small towns and suburbs. But I recall discussing who was visiting whom because we could see their cars parked outside someone’s house.

Were these the only two Australian novels I had read, I might have thought that all Australian literature was essentially suburban, but a couple of months ago I read The glade within the grove, also set in Sydney (and southern New South Wales), about the founding of a hippie commune.

But the book does give a rather detailed picture of suburban life and concerns in the 1970s.

July 26, 2016

First Impressions of Charles Williams

In most fantasy novels, the characters leave the ordinary world and enter into a fantastic world. Harry Potter exchanges his aunt and uncle’s home for Hogwarts, Lucy enters Narnia through a wardrobe, and even Bilbo Baggins leaves his comfortable hobbit hole for a world of danger and adventure. In Charles Williams’ The Place of the Lion, the situation is reversed–the fantastic world crashes into the ordinary world through the appearance of the Archetypes.

In reading this novel for the first time, I was most struck by this reversal. It is not merely a few chosen, exceptional people who must learn to navigate a world unfamiliar to them, but rather it was an entire village of ordinary people that had to face the fantastic world invading their own. Some embrace the Archetypes, some are driven to madness, and some are driven to fear. The main character Anthony Durrant acknowledges feeling…

View original post 362 more words

July 24, 2016

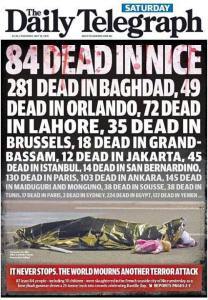

The madness in the world

A few days ago I wrote about how I thought that the world was going mad in ways, or to an extent that I had not experienced before. Yes, there has always been evil in the world. There have been wars and rumours of wars. Ten years ago Israel was bombing Lebanon. Twenty years ago Yugoslavia was disintegrating in violence. In every age bad things have happened. But now, somehow, it seems worse.

Something is in the air.

People seem to be divided as never before.

A month ago the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (UK) had a referendum on whether they should remain in the European Union or not. England and Wales voted to leave, Scotland and Northern Ireland voted to remain in the EU. Do it has raised the question whether Scotland and Ireland should remain in the UK. The referendum has revealed deep and bitter divisions, not merely in the country, but in political parties. The Labour Party, for one, seems to be tearing itself apart.

Something is in the air.

Since the Internet reached South Africa in about 1990 we’ve been able to observe at first-hand the bitter rivalry of the USA’s Tweedledum and Tweedledee presidential elections, where the candidates, when elected, bomb the same countries that their opponents would have bombed if they had been elected. But this time round the divisions seem deeper. As in the UK, the political parties themselves seem divided. The Democratic Party seems to be divided in the same way as the Labour Party in the UK — The Political Compass:

Despite most polls indicating that Bernie Sanders would fare significantly better than Clinton against Trump, the party clearly wanted Hillary. This surely suggests that when push comes to shove, the Democratic establishment would prefer Hillary to lose the presidency than Sanders to win it. On the other hand, a large section of the GOP mainstream is probably uncomfortable enough with their blustering billionaire to swing behind Hillary — but never Sanders.

Something is in the air.

And now I discover that I’m not alone in thinking this. An Orthodox priest in the USA writes Why I Must Oppose Donald Trump: One Priest’s Perspective – Saved Together:

Whether in the public sphere, or sadly, even among family and friends, or communities I have witnessed the very swift decline of exchange of ideas, benefit of doubt, and allowance of nuance. I have certainly been guilty of contributing to this decline, perhaps even as I sit down to write this blog post. But I think about this a great deal when I reflect on why I feel such a heavy weight about discourse on issues, on politics, on morality or ethics. Certainly “there is nothing new under the sun” and I have recognized there is a definite hubris in thinking of the current era as being more significant, better or worse, than others. However I must admit that I have felt the weight more acutely of the disconnect, the fog, the fear, in the past few years than I ever have before.

Something is in the air.

That puts it far better than I can, and I commend that blog article to anyone reading this.

In South Africa too we see something similar. In some places the ANC is tearing itself apart over the nomination of candidates for local government elections. Three weeks ago we saw buses being burnt and shops being looted because some ANC members were dissatisfied: their favoured candidates had not been nominated.

Most of the attempts at analysing this seem shallow, or to miss the point. There is plenty of anti-Trump rhetoric in the USA, which you can see in the social media, but much of it is as crude, vindictive and facile as Trump’s own rhetoric, accompanied by the ugliest pictures of Trump that people can find. There seems to be an assumption, at least in the mainstream media, that since Trump uses racist and xenophobic rhetoric, all his supporters must simply be racist xenophobes. And in the UK there is the similar assumption that because Nigel Farage used racist and xenophobic rhetoric, all those who supported #Brexit must be racist xenophobes too.

Most of the attempts at analysing this seem shallow, or to miss the point. There is plenty of anti-Trump rhetoric in the USA, which you can see in the social media, but much of it is as crude, vindictive and facile as Trump’s own rhetoric, accompanied by the ugliest pictures of Trump that people can find. There seems to be an assumption, at least in the mainstream media, that since Trump uses racist and xenophobic rhetoric, all his supporters must simply be racist xenophobes. And in the UK there is the similar assumption that because Nigel Farage used racist and xenophobic rhetoric, all those who supported #Brexit must be racist xenophobes too.

I think this article captures something important that is often overlooked, and I think it also applies, mutatis mutandis, to UK #Brexit supporters and South African EFF supporters as well, many of whom are in a similar demographic group — Millions of ordinary Americans support Donald Trump. Here’s why | Thomas Frank | The Guardian:

This gold-plated buffoon has in turn drawn the enthusiastic endorsement of leading racists from across the spectrum of intolerance, a gorgeous mosaic of haters, each of them quivering excitedly at the prospect of getting a real, honest-to-god bigot in the White House.

All this stuff is so insane, so wildly outrageous, that the commentariat has deemed it to be the entirety of the Trump campaign. Trump appears to be a racist, so racism must be what motivates his armies of followers. And so, on Saturday, New York Times columnist Timothy Egan blamed none other than “the people” for Trump’s racism: “Donald Trump’s supporters know exactly what he stands for: hatred of immigrants, racial superiority, a sneering disregard of the basic civility that binds a society.”

But the article goes on to point out that what may be attractive to many Trump supporters is something else — trade.

Donald Trump talked about trade. In fact, to judge by how much time he spent talking about it, trade may be his single biggest concern – not white supremacy. Not even his plan to build a wall along the Mexican border, the issue that first won him political fame. He did it again during the debate on 3 March: asked about his political excommunication by Mitt Romney, he chose to pivot and talk about … trade.

It seems to obsess him: the destructive free-trade deals our leaders have made, the many companies that have moved their production facilities to other lands, the phone calls he will make to those companies’ CEOs in order to threaten them with steep tariffs unless they move back to the US.

And it is here where I think one may find similar demographic groups supporting #Brexit in the UK, and the EFF in South Africa.

There’s a video going around on the internet these days that shows a room full of workers at a Carrier air conditioning plant in Indiana being told by an officer of the company that the factory is being moved to Monterrey, Mexico, and that they’re all going to lose their jobs.

NAFTA, the North American Free Trade Agreement, isn’t a full-blown common market like the EU, but the principle is much the same. Ever since Maggie Thatcher destroyed Britain’s mining and manufacturing industries and turned the Brits into a nation of hairdressers, there has been much the same problem there, and in the eyes of many of those affected that problem has been exacerbated by the EU.

In South Africa there is a somewhat different history. During the apartheid era sanctions drove the government to strive for autarky, for rather similar reasons to those of the Hoxha regime in Albania. This meant that a lot of manufacturing industries developed, protected by high tariff walls and sanctions. These were not especially beneficial to workers, however, because the government’s policy of “border industries” created a border with labour (black) on one side of the border and capital (white) on the other.

But what happened after the end of apartheid?

Most of the manufacturing was outsourced to other countries, with consequent unemployment at home. The ANC, though it promised “jobs”, bowed to foreign pressure. Instead of manufacturing vehicles in South Africa, many factories reverted to assembling knocked-down kits. The actual manufacturing was moved offshore. And the same thing happened in the textile industry. Most of the clothing that people buy nowadays comes from Asia. A few years ago we saw a huge Chinese emporium in the little border town of Oshikango in Ovamboland, northern Namibia (see here). What does China buy from Ovamboland? The trade seems to be all one way, yet before 1970 Ovamboland had autarky.

There have been other factors at work in South Africa, which may or may not apply in the USA and UK. During the apartheid era, labour relations were handled by the police on behalf of the management. If there was a labour dispute, management called in the police to pacify the workers with teargas and rubber bullets, and put them in their place. There is much talk of “transformation”, but little has changed in that respect — witness the Marikana massacre of a few years ago. Unlike manufacturing, it wasn’t possible to move the platinum mines overseas, and the result showed that in spite of enlightened labour legislation, little has really changed.

In all this there are three parties, or perhaps four — management, workers, government and consumers. And part of the problem is intransigence on the part of both management and workers. That too has transformed little since the days of apartheid. But part of the problem is also the ANC’s Thatcherism, and having bought into neoliberal economics.

And so I suspect that the EFF appeals to much the same demographic group as that which voted for #Brexit in the UK, and supports Trump in the USA. In spite of the “global village” created by the Internet, human divisions seem to be growing wider and deeper, with little communication across the barriers.

July 21, 2016

Glimpses of English Christianity 50 years ago

Fifty years ago today I had some interesting glimpses into the varieties of English Christianity. First I was invited to, and attended a garden party of the Archbishop of Canterbury at Lambeth Palace. The Archbishop was the Most Revd Dr Michael Ramsey, and the garden party was for representatives of “the church overseas”, which consisted of Church of England missionaries serving overseas who happened to be home, and members of Anglican churches elsewhere who happened to be in England.

Lambeth Palace, official residence of the Archbishop of Canterbury, 22 July 1966

I had been in England for six months, having arrived in January 1966, and was working as a bus driver for London Transport while waiting for the new academic year to begin, when I would attend St Chad’s College in Durham for postgraduate studies in theology. So I got an invitation and after work I went to Lambeth Palace to meet the Archbishop of

Canterbury – the Archbishop’s reception of missionaries and overseas visitors, so the card said. I turned up at the gate at

3:00 pm, and joined the queue in the courtyard, all waiting to shake hands with the Archbishop. It was bright and sunny after three days of rain. Everyone had little coloured cards to show what part of the world they came from. The Archplus, on shaking hands, said “How dyoo doo?”, and Mrs Plus, standing next to him, repeated the shibboleth.[1] It is apparently a rhetorical question, like the laity’s “Ow you orrite?” — no answer is expected. I wrote in my diary

It sent tingles down my spine to hear the way they said it; it sounded out of this world and untrue. Narnia and Hobbitland and Jorn of Jorna have far more credibility. On shaking hands with the archplus, we passed into the library, which was filled with a milling throng all having tea.

Feeling isolated and overwhelmed, I crept into a narrow space between the bookshelves and a display cabinet, where I could observe from a relatively safe vantage point. I looked to see who was next to me — a short black man from Malawi. I tried an experimental smile, and he said “Hello”, and thus we got talking, and I found that he lives practically next door to Biddy Bailey, and was a lay reader in the church she goes to.[2]

A little later I was button-holed by a couple of nuns from Wantage, and so had to confess to them that I had at one time been a server at St Mary’s School in Waverley and that I knew Father Comber and all.[3] Then a little later saw Fr Neil Bliss, the man who was at Piet Retief when we were there in September. He does not appear to like Piet Retief, and is a very strange sort of bloke. Then I saw Desmond Tutu, and finally Father Sweet, and hung around with him and Mrs Sweet the rest of the time I was there.[4]

We wandered around the archbishop’s dwelling, with Mervyn Sweet making irreverent remarks about the palace and its furnishings. He wanted to remove a table which he thought would be suitable as a nave altar, and then one of the crosses (of which there were many), from archplus Michael’s private chapel, remarking “I suppose even archbishops pray.”

The Archbishop of Canterbury’s Garden Party for the reception of missionaries and overseas visitors, 22 July 1966

We then wandered round the garden taking photographs, and then there was Evensong and a commendation of missionaries in the archbishop’s private chapel. We went in late, and sat in the front row, right underneath the pulpit, and the archbishop when he preached looked and sounded excruciatingly funny, being exactly after the image of a caricature

clergyman, looking as if he were about to burst into tears at any minute, and saying his piece in a lilting sing-song clerical voice. What he had to say wasn’t too bad, however, and nor were some of the prayers he said — praying for peace in Vietnam, for example.

Revd Mervyn Sweet, former Vicar of St Alphege’s Church, Pietermaritzburg, 22 July 1966

Afterwards we met briefly an English priest who was shortly going to Cape Town, and then had a look at the immersion font, which had a text about resurrection carved around it. Mervyn Sweet was ecstatic that there was someone in the church who had a theology of baptism, instead of putting in stupid texts about “suffer the little children to come unto me” or pictures of John the Baptist baptising Jesus.

I walked with them over to where they had parked their car, and they said they were going to Merstham in Surrey for their holidays, and said I should go and see them there. After they left I saw Desmond and Leah Tutu again, and we had more time to chat. Their daughter, aged about 2 or 3, was with them, and they said she was called Pussy, and only answered to that, and not to her real name. He said he was assistant priest in a rather posh parish in Bletchingly, and had landed with his bum in the butter. The people in the parish were very kind to him.

Joan Sweet, Lambeth Palace, 22 July 1966

I went to Leicester Square and had supper at an Indian restaurant there. English cooking was horrible back then and so I often ate in Indian, Chinese or Italian restaurants. But English cooking has since improved, perhaps as a result of so many foodie TV shows with their celebrity chefs.

After supper I made my way to Chalk Farm to a gathering of the Christian Committee of 100. It sounds impressive, but in fact there were only three of us — Peggie Denny, Peggy Smith and me.[5] We were planning a march to the American Embassy to protest against the war in Vietnam, It was in marked contrast with the garden party at Lambeth Palace that afternoon, whose opulent surroundings spoke of wealth and power, and the three of us gathered in a humble flat. Christianity in Britain had many different faces. We decided not to call it a march, but rather a procession, and designed leaflets to hand out to people in the streets as we went, to explain about the Vietnam War, and why Christians should not support it.

_______

Notes

[1] I am not sure if it is still the custom, but back then Anglican bishops used to sign letters and other documents with a + in front of their names, and I seem to recall that archbishops used two. So the Anglican Bishop of Natal (where I came from), Vernon Inman, would sign his name +Vernon Natal and was usually referred to as “Plus Vernon”. I think the Archbishop of Canterbury signed his name as ++Michael Cantuar, but I didn’t keep the invitation card, so can’t be sure of that.

[2] Bridget Bailey was a friend and fellow student from the University of Natal in Pietermaritzburg. She had graduated in botany and zoology in 1965 and got a job in Malawi. Exactly 10 years after the garden party (ie 40 years ago today) we were on holiday, and stayed with Bridget Bailey’s mother in Bloemfontein.

[3] The Community of St Mary the Virgin (CSMV) sisters had their mother house at Wantage in Oxfordshire, and also ran a girls school in the nearby town of Abingdon in Berkshire, where the school chaplain was the Revd Thomas Comber. The CSMV sisters also ran some schools and other institutions in South Africa, including St Mary’s School for Girls in Waverley, Johannesburg. Fr Tom Comber had been Anglican chaplain at Wits University and St Mary’s School, and recruited some of the male students as altar servers for the school chapel, where services were held on Sundays for the nuns and the boarders. Two of the girls, dressed in albs, acted as acolytes, carrying candles, but only boys were allowed to enter the sanctuary with the priest in Anglican churches those days.

[4] I was rather relieved to see some people that I knew. Desmond Tutu, who later became Anglican Archbishop of Cape Town, I had known as a student at St Peter’s College in Rosettenville, Johannesburg, a few years earlier. The Revd Mervyn Sweet, like Tom Comber, had been a university chaplain in Pietermaritzburg until the end of 1964, and also parish priest at St Alphege’s Church in Scottsville, where the university campus was.

[5] The Committee of 100 was a more radical arm of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) which favoured non-violent direct action. Though it included Christian members, many of its leaders were prominent secularists, like Bertrand Russell, and there were frequent arguments about aims and methods, particularly over whether non-violence was a principle or merely a tactic. The Christian Committee of 100 was formed by Christian pacifists of various denominations with similar aims, though with a more Christian focus.

July 17, 2016

Is the whole world going mad?

It seems that the world has gone manic-depressive, or, as they prefer to say nowadays, bipolar.

I’m reminded of an old Cold War song by Jeremy Taylor:

Well one fine day I’ll make my way

to 10 Downing Street

“Good day,” I’ll say, I’ve come a long way

Excuse my naked feet.

But I lack, you see, the energy

to buy a pair of shoes

I lose the zest to look my best

When I read the daily news

’cause it appears you’ve got an atom bomb

That’ll blow us all to hell and gone

if I’ve got to die then why should I

give a damn if my boots aren’t on?”

Three cheers for the army and all the boys in blue

Three cheers for the scientists and politicians too

Three cheers for the future years, when we shall surely reap

all the joys of living on a nuclear rubbish heap.

So what to I see when I read the daily news?

The West escalates with Russia: Make no mistake, a second Cold War is now official NATO policy – Salon.com

Nice attack: Man loses six members of his family in Bastille Day lorry massacre | World | News | London Evening Standard

Data on drone civilian deaths shows problems | Opinion | wiscnews.com

Brutal backlash against Turkey coup as mobs behead rebel soldiers in the streets – Mirror Online

Baghdad bombing: Death toll rises to nearly 300 in Isis car bombing | Middle East | News | The Independent

Hundreds arrested as anger boils over police violence in US | Africanews

Hawks probing whether senior ANC members behind Tshwane violence | National | BDlive

The next Boko Haram? Nigerian attacks raise fears of new ‘terror’ threat | World news | The Guardian

Nigerian refugee who fled Boko Haram beaten to death in alleged racist attack in Italy

Does reading that kind of news bother you?

Don’t worry, you can always restore your equanimity with thoughts like these:

4 Reasons Why You Should Never Say “All Lives Matter” | Gurl.com

Do any of these lives matter?

Thanks to the Internet, we have seen how polarised people in the USA have been on political issues, when presidents from the two main parties with equally rebarbative policies are vilified by people opposed to them in an over-the-top way. In the 1990s it was KKKlinton, followed by the Shrub, followed by Obomber — war criminals all, of course, but why should the people who elect them be so partisan about which war criminal they choose?

The UK never displayed quite such partisanship until the referendum on leaving the UK. That really seems to have divided the nation, to judge from the rants I see from both sides on the Internet. And it seems to have divided the political parties as well.

The media in both those countries have consistently beaten the war drums, and encouraged the election of warmongers, and vilified those who are less than enthusiastic about war, like Charles Kennedy, Bernie Sanders and Jeremy Corbyn. And the media are still doing it, if this article is anything to go by:

The Media’s Incessant Barrage of Evidence-Free Accusations Against Russia | The Nation

The media seem hell-bent on starting the Third World War, and if it goes nuclear, then no lives will matter. As another 1960s song put it, We will all go together when we go.

So the US and the UK are bipolar, and becoming more polarised. In the US it seems to be becoming a shooting war, as more citizens are gunned down by police, or by others with a grudge against someone or something. And in the UK one MP was gunned down during the referendum — a sign of things to come?

Closer to home in South Africa, we have similar party in-fighting, with ANC members murdering each other about nominations for election. Political back-stabbing, both literal and figurative, seems to be on the increase all over.

I lived through the Cold War. When I was in Standard 2 (Grade 4) at a school in the Magaliesberg we would point at the ridge across the valley and say to each other “What would you do if a thousand North Koreans came over that hill?” We saw the illustrated articles in Popular Mechanics which explained how napalm bombs worked, and how they would be dropped at each end of a railway tunnel when a train was passing through, thus incinerating everyone on board. But those things were happening in one country 10000 miles away. Now people are being massacred every week, in different countries on different continents. What is it? Over-population, like rats in a cage? When rats are crowded together in confined quarters, it seems they go mad and kill each other, and now human beings seem to be behaving in the same way.

I lived through the Cold War. When I was in Standard 2 (Grade 4) at a school in the Magaliesberg we would point at the ridge across the valley and say to each other “What would you do if a thousand North Koreans came over that hill?” We saw the illustrated articles in Popular Mechanics which explained how napalm bombs worked, and how they would be dropped at each end of a railway tunnel when a train was passing through, thus incinerating everyone on board. But those things were happening in one country 10000 miles away. Now people are being massacred every week, in different countries on different continents. What is it? Over-population, like rats in a cage? When rats are crowded together in confined quarters, it seems they go mad and kill each other, and now human beings seem to be behaving in the same way.

We read about how those whose motto is “To serve and protect” behave as if it were “To bully and beat up”, and whether it happens in Baton Rouge or Marikana, it still looks like the behaviour of the rats in Universe 25.

We look at the Disunited Kingdom, disintegrating after the Brexit referendum, or the Disunited States, offered a choice between a warmonger and a racist, both tearing themselves apart, and these are the self-proclaimed leaders of the “free” world. Perhaps there is a tiny glimmer of hope in Theresa May, the new British Prime Minister.

Theresa May suggests Brexit delay as she says no Article 50 until Scotland gives go-ahead

There is at least a recognition that two of the four countries that comprise the UK voted to leave the EU and two of them didn’t. The ones that didn’t vote to leave the EU now realise that they can no longer belong to both the EU and the UK, and Theresa May at least realises that a solution to that problem needs to be negotiated. It can only be hoped that she will approach other problems with a desire for negotiation rather than belligerent rhetoric spilling over into armed force.

Theresa May’s genius may be her dull Anglican ways | London Evening Standard:

Who’d have thought that she’d be the person to call for a Britain that works “for everyone, not just the privileged few” or that she’d be calling for German- style worker representation on company boards? (She did also mention the gender pay gap but only after talking about class and race as impediments to social mobility.) Her views on hostile takeovers of British companies are way more radical than David Cameron’s but because they’re delivered in an understated fashion, their radicalism doesn’t really register.

That may be the real genius of Mrs May — not as a feminist but as a vicar’s daughter whose social agenda is unnoticed because it’s delivered in that unthreatening, not to say, dull C of E fashion. But it does it for me.

The agony and ecstasy of Saint Theresa, the vicar’s daughter | Giles Fraser | The Guardian:

This was the formative world of the new prime minister – unflashy service, community, warts and all, and personal sacrifice. The Christian faith “is part of me. It is part of who I am and therefore how I approach things”, she said. And, unlike the patchy public school religion of her predecessor, her faith feels entirely convincing to me.

If the world is in a mess, can the church help? If the world is divided, can the Christian communities show a more excellent way?

Unfortunately, it seem that the Church is as divided as the world.

The recent Pan-Orthodox Council held in Crete was meant to at least get Orthodox Christians talking to each other, and if they couldn’t agree, at least identify areas of disagreement and begin to deal with them. Instead, it produced this:

Athonite Fathers call for Rejection of Cretan Council and Cessation of Commemoration of the Patriarch of Constantinople / OrthoChristian.Com

If the governing body of the Holy Mountain accedes to that, the world would be quite justified in saying to the Church, “Physician, heal thyself.” The Church, far from being a hospital for sinners, would be a bunch of lunatics with no asylum.

So is there any hope?

I was feeling pretty pessimistic when I started writing this post. I thought the world was going to hell, not in a handbasket but in a Formula I racing car.

And then I saw this. It’s not from an Orthodox source. Perhaps it’s not even from a Christian source, but I found it encouraging and you might too.

My friends, do not lose heart. We were made for these times. I have heard from so many recently who are deeply and properly bewildered. They are concerned about the state of affairs in our world now. Ours is a time of almost daily astonishment and often righteous rage over the latest degradations of what matters most to civilized, visionary people.

You are right in your assessments. The lustre and hubris some have aspired to while endorsing acts so heinous against children, elders, everyday people, the poor, the unguarded, the helpless, is breathtaking. Yet, I urge you, ask you, gentle you, to please not spend your spirit dry by bewailing these difficult times. Especially do not lose hope. Most particularly because, the fact is that we were made for these times. Yes. For years, we have been learning, practicing, been in training for and just waiting to meet on this exact plain of engagement.

If that speaks to you, go ahead and follow the link and read it all.

And in the mean time I shall continue to pray the Morning Prayer of the Last Elders of Optina.

July 16, 2016

Pilgrimage for Peace in Ukraine

Seen on Facebook: A procession called “Prayers for peace and love in Ukraine” is taking place from July 3 to 27. Thousands of clergy, monks and prilgrims are walking with little breaks constantly praying, with microphones singing hymns, Akathists and saying prayers. Priests sprinkling holy water, many people getting out of their cars and getting baptized. Children throwing flowers on the road in front of the Mother of God icon. At a monastery a layer of flowers is already prepared.

Thousands of believers join the all-Ukrainian cross procession at Pochaev Lavra / OrthoChristian.Com:

In the morning of July 9 right after a prayer service at the Dormition Cathedral the all-Ukrainian procession of the cross started from the Holy Dormition Pochaev Lavra, reports the information and education department of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC MP).

The procession of peace, love and prayer for the Ukraine is headed by Metropolitan Sergy of Ternopil and Kremenets, Metropolitan Vladimir of Pochaev, the Lavra’s abbot, Bishop Seraphim of Shuya, Rector of the Pochaev Theological Seminary. and All the Ukraine July 3 to 27.

The all-Ukrainian cross procession of peace, love and prayer for the Ukraine is being held with the blessing of His Beatitude Metropolitan Onufry of Kiev and All the Ukraine July 3 to 27.

On July 3 the faithful setting off from the Holy Dormition Svyatogorsk Lavra walked through the Donetsk region, reached the Kharkiv region and are currently moving towards the Ukrainian capital of Kiev. On July 28, the Day of Baptism of Russia, the two cross processions will meet at the Holy Dormition Kiev Caves Lavra. At the end of the all-Ukrainian cross procession of peace and love a prayer service will be celebrated at Vladimirskaya Gorka (the St. Vladimir’s Hill).

But not everyone is happy about this.

On the evening of July 12 young people in camouflage from “the Right Sector” extremist group along with paid activists arranged a provocation during the all-Ukrainian cross procession on the way from Svyatogorsk to Kiev, reports the Information and Education Department of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC MP).

On that day the cross procession participants were to walk from Valki to Chudovo and finally reach Poltava.

At the border of the Kharkiv and Poltava regions the faithful were met aggressively by extremists in automobiles along with several members of the Azov battalion. A column of the provocateurs walked parallel to the pilgrims, crying out rude insulting slogans and all sorts of slander, intimidating the faithful, and defiantly filming their own provocation.

A nationalist counter-demonstration

July 11, 2016

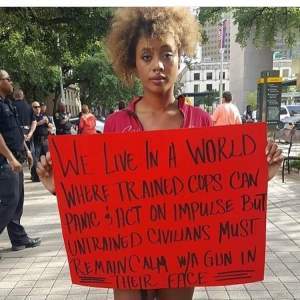

How anti-racism became racist: All lives matter

I keep seeing more and more articles and links to articles like the following:

Why you should stop saying “all lives matter,” explained in 9 different ways – Vox

It’s Time You Realize #AllLivesMatter Is Racist | Advocate.com

The Problem with Saying ‘All Lives Matter’ | RELEVANT Magazine

‘All lives matter’ is and always was racist | The Guardian

These headlines are factoids.

A factoid is a lie that is repeated so often in the media that people eventually come to believe it is true.

In reading those articles, I can only think that the people who write them have lost their moral compass, or their sense of logic or both.

If one takes a charitable view of it, one could say that the logical and moral flaw is assuming that if people say the right thing for the wrong reasons, then the right thing becomes wrong.

A less charitable view is that those who maintain that “all lives matter” is wrong really believe that some lives matter more than others.

In either case, the denigration of “all lives matter” is American exceptionalism at its worst.

The logical flaw in this is illustrated in a cartoon that was attached to the first article listed above:

This cartoon is altogether disingenuous, and thoroughly misrepresents the meaning of “all lives matter”.

It would be more accurate if it showed several burning houses, and the “all houses matter” people would be trying to put out the fires in all of them, while that ones who don’t believe “all houses matter” would be spraying water on some houses, and petrol on the others to make them burn faster.

A few months ago there was a terrorist attack in France, and Facebook offered its users a French flag to cover their profile picture to indicate solidarity with the victims. Last week there was a terrorist attack in Iraq, and there were many more victims than in the French attack, but Facebook did not offer its users an Iraqi flag. The people at Facebook clearly believe that French lives matter, but Iraqi lives don’t matter as much. But they are not racist, oh no! It’s believing that all lives matter that is racist. Believing that some lives, like French lives, matter more than other lives, like Iraqi lives, is not racist, according to the arbiters of political correctness who wrote the articles cited above.

But we live in an Orwellian world where nonracism is racism and antiracism is racism.

If believing that all lives matter is racist, then the term “racism” has lost its meaning.

I’ve written about this before: on the American exceptionalism aspect of it here, and in relation to Black Lives Matter here. But it seems to me that it is getting worse, that logic and moral sense have flown out of the window. The meme that believing that all lives matter is racist has become a factoid, and it really needs to be stopped.

So I repeat:

If people say the right thing for the wrong reasons, that does not make the right thing wrong.

Unless, of course, you really do believe that not all lives matter.

July 8, 2016

G.K. Chesterton, distributism, communitarianism and more

We had another of our book chats over coffee yesterday, and Duncan Reyburn, free for the university vacation, joined us, and told us something about his soon-to-be published book on G.K. Chesterton. And it seems that once that is published, he’ll be starting another.

In the ensuing conversation quite a lot of books were mentioned, and I’ll give links to some of them, in case anyone (including me) wants to look them up.

Duncan remarked that G.K. Chesterton had a very good memory, and could remember the plots of 10000 novels. I try to make notes of books that I read, but find that I sometimes can’t remember the plots of novels even when I read the notes I made at the time, so I think Chesterton’s feat was pretty impressive.

One of the central points of Duncan’s book is discovering the extraordinary in the ordinary, and one’s sense of astonishment in the commonplace. Chesterton thought that we should never lose our sense of astonishment at the things that are closest to us. I recalled reading Nausea by Jean-Paul Sartre, in which the protagonist looks at something ordinary — he is sitting on a park bench and looking at a tree root, and finds it utterly alien, and is indeed nauseated by it. Chesterton, on the other had, sees such things as commonplace, and finds their strangeness delightful.

David Levey mentioned Ndebele’s influential book Rediscovery of the Ordinary: Essays on South African Literature and Culture, which seems to have a similar theme, and I’ve put it on my “want to read” list. David also mentioned Chesterton’s poem The Battle of Lepanto. The poem was written in 1920, the battle took place in 1571, and remarks that “the site Catholic Culture calls the said naval battle, between Catholics and Turkish Muslims, ‘the battle that saved Europe’, which implies rather a lot.” My memory of that period of history is somewhat rusty, but I thought Venetian trading monopolies had quite a bit to do with it too.

We also discussed the phenomenon of the American religious right apparently trying to claim Chesterton as one of their own, which seems rather odd, since Chesterton was, by his own admission, that bête noire of the American Right, a liberal.

We touched briefly on Chesteron’s notion of political economy, Distributism, which I thought had quite a lot in common with Dorthy Day’s Communitarianism. I recommended that Duncan read Jim Forrest’s biography of Dorothy Day, All is Grace. We discussed briefly the differences between individualism, collectivism and communitarianism, and what I had to say on it is mostly set out in a couple of blog bosts — Individualism, Collectivism and Communitarianism, and you can find some more links here: Socialism, Communitarianism, Distributism.

I thought I’d better check some of this with Jim Forrest, the biographer of Dorothy Day, since he actually knew and worked with her, and he said, “Dorothy and the Catholic Worker embraced distributism wholeheartedly. As my friend Tom Cornell wrote not long ago:

In economics, anarchists call for more capital to more people. The distributists G.K. Chesterton, Hilaire Belloc, Eric Gill and Fr. Vincent McNabb strongly influenced the Catholic Worker in its formative years. They held that law and government should promote crafts, small worker-owned and managed industry and farms. Individuals and small groups should take the initiative and not wait for government action.

Back in the 1990s I thought that the ANC’s original Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) looked quite a bit like that, and would at least encourage it. But within a year it was exchanged for the Neoliberal GEAR programme instead.

Another book that Duncan Reyburn mentioned in the course of conversation was Unapologetic: Why, despite everything, Christianity can still make surprising emotional sense, by Francis Spufford. He recommended it especially for those who are bothered by the new militant atheists like Richard Dawkins and Sam Harris. He also recommended a film, The Tree of Life, which is a retelling of the story of Job in a modern setting.

Well those are the things I remember (and some I wanted reminders of) from our NeoInklings Literary Coffee Klatsch this month. If you live in or near Tshwane and would like to join us for free-ranging discussions on Christianity and literature, and sometimes presenting your own work (as Duncan Reyburn did this time), we meet at 10:30 am on the first Thursday of the month at Cafe 41, at the corner of Eastwood Road and Pretorius Street, Arcadia.

Cafe 41, venue for our month;y book discussions

June 27, 2016

Is Nick Clegg clairvoyant? So am I

Someone shared this article on Facebook this morning, Nick Clegg predicted the future with stunning accuracy. I thought it was a pity that his clairvoyance developed only after his disastrous coalition with the Tories.

But when I read my diary of 50 years ago, perhaps I had a bit of clairvoyance of my own. I was far from home, in London, sitting in Brixton bus garage in a break between driving buses between Croydon and the Embankment, under western eyes, and I was reading Joseph Conrad’s Under Western Eyes. And when I finished my shift at 8 pm I stopped at the “Horse and Groom” in Streatham High Street for a sandwich on my way back to my gloomy bed-sit and read this:

In real revolution, not a simple dynastic change or reform of institutions — in a real revolution the best characters do not come to the front. A violent revolution falls into the hands of narrow-minded fanatics and tyrannical hypocrites at first. Afterwards comes the turn of all the pretentious intellectual failures of the time. Such are the chiefs and the leaders. You will notice that I have left out the mere rogues. The scrupulous and the just, the noble, humane and devoted natures; the unselfish and intelligent may begin a movement, but it passes away from them. They are not the leaders of the revolution. They are its victims. The victims of disgust, of disenchantment, often of remorse. Hopes grotesquely betrayed, ideals caricatured, that is the definition of revolutionary success. There have been in every revolution hearts broken by such

successes.

And when I got home I wrote in my diary:

And I think that will be the same in the South African revolution. The great men: Albert Luthuli, Bram Fischer, J.H. Hofmeyer, Alan Paton, Nelson Mandela, Robert Sobukwe, Peter Brown and many others the champions of freedom and justice, they, like Moses, will not live to enter the promised land. And when the promised land is entered at last, the promises will be betrayed, hopes destroyed, ideals caricatured. This is almost inevitable, but we carry on just the same. The Lord will provide.

And so it has turned out.

Under Western Eyes by Joseph Conrad

Under Western Eyes by Joseph Conrad

I finished reading the book the following day and read the old man’s description of Natalia Haldin, “It is hard to think I shall never look any more into the trustful eyes of that girl, wedded to an invincible belief in the advent of loving concord, springing like a heavenly flower from the soil of men’s earth, soaked in blood, torn by struggles, watered with tears.”

And that put me in mind of the Ascension Day hymn:

He shall come down like showers upon the fruitful earth;

Love, joy, and hope, like flowers, spring in His path to birth.

Before Him, on the mountains, shall peace, the herald, go,

And righteousness, in fountains, from hill to valley flow.

And so every revolution betrays its children. While we live in this world, this secular age, we can never rest and think that because we have won our freedom we will remain free. The struggle continues. A luta continua. Die stryd duur voort.