Stephen Hayes's Blog, page 41

March 1, 2016

Compline in Seattle

A few years ago there used to be debates in the Christian blogosphere about “attactional” versus “missional” churches. I was never quite sure what the debates were really about, but I was reminded of them when I read these articles about Compline in Seattle and Evensong in university chapels:

Chant Matters – Compline at St Mark’s Cathedral, Seattle – What is in Kelvin’s Head?:

That service breaks almost (and that almost is important, as we shall see) rule in the How to Attract Young People Big Book of Church Growth.

The building is as close to hideous as makes no odds.

The choir sing from behind a pillar and can’t be seen.

You don’t get a service sheet on the way in. You don’t in fact get anything.

The service is uncompromisingly old fashioned.

The service is based around Plainsong Chant.

There are no guitars. Not one.

It is unaccompanied by anything.

You don’t get to do anything.

You don’t sing.

You don’t speak.

You don’t engage.

You don’t form community.

And still they come. Hundreds of them. Every week they come.

And there was another article, too: Looking for Britain’s future leaders? Try evensong – Telegraph:

one evening pursuit, which has been enjoying an unexpected boost in popularity in the two universities is as far from the cliché of raucous student life as it is possible to imagine – choral evensong.

College chaplains have seen a steady but noticeable increase in attendances at the early evening services which combine contemplative music with the 16th Century language of the Book of Common Prayer.

A few years ago there was quite a craze for flashmobs — people would send text messages to friends to gather in a public place at a certain time for some kind of event or happening, and some people began having flashmobs for Compline and Evansong. One of the most impressive was was when one of the “occupy” groups of a few years ago occupied an open space near St Paul’s Cathedral in London. The cathedral was closed in reaction to it, and a flashmob gathered for Flash Evensong on the cathedral steps. If you are in England, look on Twitter. You might be able to catch @FlashCompline or @FlashEvensong, or do your own.

In Orthodox Churches it is rare to have sung Compline, at least in parish churches. The only time I’ve known Great Compline to be sung is on Christmas Eve, when it is usually followed by Matins as part of the Vigil of the Nativity. And Little Compline is normally said, not sung, though it can be said anywhere.

In Orthodox Churches it is rare to have sung Compline, at least in parish churches. The only time I’ve known Great Compline to be sung is on Christmas Eve, when it is usually followed by Matins as part of the Vigil of the Nativity. And Little Compline is normally said, not sung, though it can be said anywhere.

Many parishes also do not have Vespers any more, but perhaps if Vespers were served more often, more people would attend. At St Nicholas Church in Brixton, Johannesburg, the Vespers of Forgiveness at the beginning of Great Lent is usually well attends, but less so on other occasions.

Christian worship is really something for the Christian community. It is not intended to be evangelistic. Services like Vespers and Compline are offering the time of day to God, but sometimes just doing that can speak to people more loudly than the words of evangelists.

February 29, 2016

Bandersnatch by Diana Pavlac Glyer

Multitudes of readers and movie-goers are familiar with the names and writings of C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien. Many are also aware that the two literary giants were part of a ‘club’ called The In…

Source: Bandersnatch by Diana Pavlac Glyer

February 25, 2016

Being racist and being #colourblind

Over the last few months there seems to have been an escalation of racist discourse in South Africa. A group of students at the University of Pretoria (Tukkies) started an anti-racism movement under the #colourblind hashtag to try to counter it.

We are #ColourBlind | eNCA: #ColourBlind’s call to action is that people post photos of themselves with a friend from a different race in a grayscale format accompanied by #ColourBlind.

A group of students from Tuks unite in support of the ColourBlind movement as a protest against recent racial tension on the campus. Photo: eNCA / Ditiro Selepe

On the face of it, the #colourblind hashtag looks rather naive, and could imply that it is merely trying to paper over the cracks, but it appears from this interview that the founders of the movement are aware of the dangers: Maverick Interview: #ColourBlind | Daily Maverick:

GN: What does it mean to be colour-blind?

JPVDW: One cannot be “colour-blind”; the hashtag does not refer to a state of being. It by no means aims to imply that we should ignore our diversity. Following this movement merely means that you as a student or someone in support of the student community wishes to unite under the banner of acceptance and hope in a time where students are bombarded by negative and violent factors.

GN: If we adopt a colour-blind approach, how do we at the same time acknowledge and rectify past and current racial inequalities caused by white people and inflicted on black people?

JPVDW: In the description of this movement we made it very clear that this movement is not aimed at ignoring race or nationality or any other factors. The intent of the ColourBlind movement is not to ignore the pertinent questions that deserve crucial conversations. The movement is focused on unity. If anything this movement aims to show people that the discussion on issues of the past as well as moving forward into the future cannot be done on a polarised platform, these issues belong to all of us and should be conversed on and solved together.

The hashtag #colourblind is therefore a convenient label for an anti-racist movement, not a prescription for solving the problem. But the disadvantage of trying to encapsulate something into a single slogan or hashtag is that it can be interpreted simplistically, and this tweet on Twitter points out some of the dangers:

Sanele Godlo @SaneIsGee 49m49 minutes ago

I’ll start being

#ColourBlind the day i have a white lady to wash and iron my clothes and a white man to do my garden

Cobus van Wyngaard, in his blog my contemplations | a South African conversation on just being church today also points out some of the dangers:

But because it is not the first time that these spaces are set up in response to racism in South Africa, we also need to be reminded of the problems which these spaces have left unresolved or even perpetuated in the past. This explains my kneejerk reaction, as well as the kneejerk reaction of others (which is probably what got me to write again).

But in spite of the unfortunate connotations of the #colourblind hashtag, I think that the movement itself is worth supporting, if only to counter the increasingly heated racist rhetoric that is being bandied about in social media, and in real life. It’s worth laying aside one’s preconceptions and prejudices about #colourblind, and reading the Maverick Interview: #ColourBlind | Daily Maverick and making that the starting point for discussion.

So, in accordance with the request, here’s my picture:

Gideon Iileka, Steve Hayes, Thomas Ruhozu. Kamanjab, Namibia, 5 Oct 1971 #colourblind

February 20, 2016

Bandiet: out of jail

Bandiet: out of jail by Hugh Lewin

Bandiet: out of jail by Hugh Lewin

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

Hugh Lewin was sentenced to seven years in jail for his part in sabotaging electrical installations in protest against apartheid in the 1960s. He spent the seven years in jail in Pretoria, where white “political” prisoners were kept (black ones were imprisoned on Robben Island, near Cape Town). This book is an account of his years in prison. The title of the book, “bandiet”, was the name given to convicted prisoners by the prison warders, while the prisoners referred to the warders as “boere”.

For the most part the “political” prisoners were isolated from common criminals, and enjoyed fewer privileges. They were allowed one visit and were allowed to send and receive one letter every six months. Other prisoners could have their sentences reduced for good behaviour, but the “politicals” had to serve the full term. Warders who were too friendly with them were punished.

One of the prisoners in this group, Harold Strachan, was released after serving his sentence, and the Rand Daily Mail published his account of prison conditions in 1965, which caused a public uproar, and he was soon back in jail for spilling the beans. But the publicity did lead to some improvements, and some more public scrutiny of the prison system.

Hugh Lewin also exposes the sleazy corruption that flourished in the prison system, protected by laws enforcing secrecy. Sometimes nowadays people talk as if corruption were something new, but the main difference between the 1960s and today is that today we have a constitution that protects freedom of the press, so the corruption is more easily exposed. Back then it flourished under the protection of official secrecy laws, which is why Harold Strachan soon found himself back in jail.

The first edition of Bandiet was published overseas, and banned in South Africa. The revised edition, Bandiet: out of jail, contains the complete original text, but also some additions that could not be published before, as that could have endangered those who were still in jail.

In my blog I have written a series of posts, Tales from Dystopia, anecdotes from the apartheid era in South Africa, reminders of the darkness from which we have come. This book belongs in the same category, telling it like it was. I wouldn’t include it in my series, because it is not my story but someone else’s, though in some ways the story touches me peripherally. Two of of Hugh Lewin‘s fellow prisoners were related to friends of mine, and one was a fellow-student at university with me, though I did not know him well.

One of the fellow prisoners was Marius Schoon. Though I had never met him, after he was released from prison he married Jeanette Curtis, the sister of a school friend of mine. Jeanette and their six-year-old daughter were killed by a parcel bomb sent by the South African Security Police.

One of the shortcomings of the book, I thought, was that in the revised edition, when he was able to tell all, he did not include a kind of prospography, with potted biographies of his fellow prisoners, giving something of their background, and what they were convicted of, and what happened to them after they were released. Since they were perforce a very close-knit community (though he does describe some tensions), this would have helped to broaden the story to include others. Perhaps at the time the book was first published, they would have been sufficiently well known from other sources, but few younger readers are likely to know this.

There are also some oblique references to people who were not imprisoned with him, like Looksmart. Now I know, from memory, that Looksmart Solwandle was one of the first to die in detention, but that was 50 years ago, and anyone under 65 might find it difficult to get the reference. He does, however, include quite a lot on the ill-treatment of Bram Fischer, especially in his last illness.

I don’t generally like prison books (or films) and so didn’t go out of my way to read this one, but I’m glad I did read it. I did read Darkness at noon by Arthur Koestler back in 1967, when I was studying in the UK. Though it was set in the USSR, I kept comparing it to the South African prisons described in the Strachan reports a couple of years earlier. Lewin mentions Darkness at noon, and I think that while I was reading it, Hugh Lewin was in jail in Pretoria, in very similar conditions.

February 16, 2016

Midwinter of the spirit

Midwinter of the Spirit by Phil Rickman

Midwinter of the Spirit by Phil Rickman

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

After reading The Lamp of the Wicked, which was less than impressive, I started re-reading this one to remind myself of what I liked about Phil Rickman‘s books. This one is certainly the best of Rickman’s Merrily Watkins series of books.

Merrily Watkins, Vicar of Ledwardine in the Church of England Diocese of Hereford, has some spooky experiences in the first book of the series, The Wine of Angels, and this leads to the new trendy and relevant bishop offering her the post of Diocesan Exorcist, with the more user-friendly title of “Deliverance Consultant”. She attends a course on deliverance ministry in Wales, led by the Revd Huw Owen, and almost immediately after returning from the course finds herself inundated with “deliverance” work, leading to her churchwarden complaining that she is not spending enough time in the parish.

To add to her difficulties her teenage daughter Jane is going through a New Age phase, and alternates between despising the deliverance ministry as “soul police” and regarding the Church of England as so totally lacking in spirituality as to be incompetent to handle anything spiritual at all.

With a plot involving ley lines, pagan sacrifices, ghosts, demon possession, satanism, suicide and even murder, Merrily Watkins find enemies and allies in unexpected places.

With a great deal packed into a small space, the plot is somewhat overheated and over the top, though the individual incidents are all quite believable, and one can accept them for the sake of the story. It’s a supernatural thriller, but there is always the ambiguity of everything that happens also having a natural and rational explanation. This prevents Phil Rickman’s books from turning into something like Frank Peretti or even Stephen King. It also presents something of the variety of the religious landscape of turn-of-the-century Britain.

In this sense Midwinter of the spirit probably marks Phil Rickman‘s high point. The later ones degenerate into rather run-of-the-mill whodunits, with the “deliverance” aspect played down. In The Lamp of the Wicked it looks as though Rickman is trying to write Huw Owen out of the series, or at least to write him off as an incompetent bumbler.

February 15, 2016

The Last Supper | New Vessel Press

“More than any other recent book, this work sets out with absolute clarity and sometimes uncomfortable honesty the intolerable reality of life for Christians in the Middle East today … a deeply intelligent picture of the situation, without cheap polemic or axe-grinding, this is a very important survey indeed.”—Former Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams, Master of Magdalene College, Cambridge University on The Last Supper

Source: The Last Supper | New Vessel Press

February 13, 2016

Milton, Lewis, Pullman, and pop culture

Yesterday we went to the second part of David Levey’s paper on “Reading Irreligiously” (for the first part see TGIF: reading irreligiously | Khanya). Much of the paper was devoted to a comparison of Milton’s Paradise Lost with C.S. Lewis’s Narnia stories, and Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy.

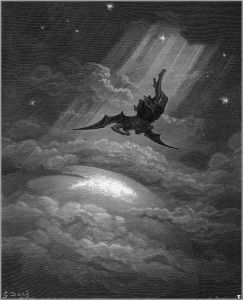

Gustave Doré’s illustration for Milton’s Paradise Lost, III,

I’m not going to try to summarise David Levey’s paper, but will rather try to respond to some of the questions he raises. Perhaps the first thing I should do is confess that I have not read Paradise Lost because I am prejudiced against Milton. I blame Milton for the conception that many English-speaking people have of the devil or satan as Lucifer, and many seem to believe that this understanding is biblical.

In the Bible “Lucifer” is an epithet of the King of Babylon (Isaiah 14). The whole passage is a satire on the fall of a tyrannical ruler who thought himself the brightest star in the political firmament. This is seen theologically and typologically as an image of the fall of Satan, the type and model of earthly tyranny (Luke 10:18; John 12:31; Rev 12:9).

I suppose my prejudice was, at least in part, inspired by C.S. Lewis, who wrote in his novel Perelandra:

He had full opportunity to learn the falsity of the maxim that the Prince of Darkness is a gentleman. Again and again he felt that a suave and subtle Mephistopheles with a red cloak and rapier and a feather in his cap, or even a sombre and tragic Satan out of Paradise Lost, would have been a welcome release from the thing he was actually doomed to watch. It was not like dealing with a wicked politician at all. It was more like being set to guard an imbecile or a monkey or a very nasty child.

What Lewis describes is what Hannah Arendt called “the banality of evil”.

In David Levey’s comparison between Milton, Lewis and Pullman it soon became evident that there was also a cultural difference, linked to the time and the place in which the works were written.

David Levey’s paper says of Narnia, “No sexuality whatever: at the end Susan does not pass through to Aslan’s country because she has taken too much interest in lipstick and boys. Boys/men take lead (except for Lucy, sometimes). No violence”. But that is not true. In The Last Battle Jill Pole takes the lead in exposing “Tashlan” as a donkey in a lion skin, which rather goes against Tirion’s culture. Of Pullman’s work Levey mentions increasing sexual awareness, explicit violence, and strong emphasis on truth.

Concerning sexual awareness, I think Levey is right, but it has little to do with Susan (more on her below). For me the lack of sexuality in the Narnia series was most apparent when I rather hoped and expected that Polly and Digory would grow up and marry and live happily ever after. But they didn’t. Lewis quite explicitly expressed his distaste for any writing that suggested sexual feelings or sexual relations among children, and in the case of Polly and Digory his distaste seemed to extend even to when the children had grown up. But the thing that struck me most about His Dark Materials on first reading is Pullman’s thinly-veiled railing against Christian asceticism throughout the series, yet in the end Will and Lyra, despite their feelings for each other, opt for something very similar to Christian asceticism, and end up like Polly and Digory, though with more angst.

The fate of Susan in the Narnia stories is somewhat different. Of this Pullman said (The Cumberland River Lamp Post – An Appreciation Of C.S. Lewis):

And in The Last Battle, notoriously, there’s the turning away of Susan from the Stable (which stands for salvation) because “She’s interested in nothing nowadays except nylons and lipstick and invitations. She always was a jolly sight too keen on being grown-up.” In other words, Susan, like Cinderella, is undergoing a transition from one phase of her life to another. Lewis didn’t approve of that. He didn’t like women in general, or sexuality at all, at least at the stage in his life when he wrote the Narnia books. He was frightened and appalled at the notion of wanting to grow up. Susan, who did want to grow up, and who might have been the most interesting character in the whole cycle if she’d been allowed to, is a Cinderella in a story where the Ugly Sisters win.

This is a rather misleading account, because in The last battle Susan is allowed to grow up, but two of the other characters, one younger and one older, comment on what she has grown up into. For Jill Pole, who, as far as I can determine, was aged about 11 in the story, says, somewhat disparagingly, “she’s interested in nothing nowadays except nylons and lipstick and invitations”. I can recall having similar thoughts about older teenagers when I was 11. And Pullman’s own heroine, Lyra, who is the same age, has little time for the kind of world that Susan was interested in, which she experienced when she went to stay with Mrs Coulter in London., and quickly became aware of the superficiality of its attractions and the dangers luking beneath the surface.

If Pullman got this wrong, others got it even more wrong. So we read in The Ramshackle Vampire: Sorry, Ladies, C.S. Lewis Finds You Tedious and Icky:

The Narnia novels, which C.S. Lewis wrote as children’s stories, generally avoid sexual themes. An episode in the final book that Lewis’s readers call “the problem of Susan” thus becomes multiply alarming: it brings sexuality (teenage romance) into the series and then condemns it, and the women who express it. In The Last Battle (1956), Susan Pevensie was denied re-admission into Narnia – and thus allegorically into Heaven – because she dared develop an interest in “makeup” and “boys,” neither of which left her time for Narnia or Aslan. Several authors have subsequently addressed Lewis’s callous dismissal of Susan in their own stories.

The general picture given by these critics is that C.S. Lewis is against life and growing up and adult sexuality. This connotation of “adult” sexuality seems to be the one found in “adult” bookshops.

But The last battle does not actually mention “boys” in this context. When I first read The last battle (at the age of 24) what Jill’s comment about “nylons and lipstick and invitations” conveyed to me was the lifestyle of a fashion-obsessed social-climbing airhead.

Oh yes he is (oh yes he is), oh yes he is (oh yes he is).

His world is built ’round discotheques and parties.

This pleasure-seeking individual always looks his best

‘Cause he’s a dedicated follower of fashion. (The Kinks)

Yet that is the lifestyle that Lewis’s critics seem to regard as “grown-up”.

The other odd thing about these critics is that they claim that Susan was refused re-admission to Narnia because of “lipstick” and “boys”. This again is reading into the text something that is simply not there. Her siblings, who were presumably interested in other things, were likewise refused readmission to Narnia because they were too old. We are told nothing about what eventually happened to Susan other than that she was no longer interested in Narnia because she was so wrapped up in her fashion-conscious social-climbing lifestyle. While the others were on the train, she was possibly at a cocktail party, perhaps similar to those thrown by Mrs Coulter. It might have fallen to her, as their only surviving relative, to make the funeral arrangements, for her siblings at least.

And that brings us to popular culture, where the most admired lifestyle is apparently one of a dedicated follower of fashion, a dedicated consumer of goods like nylons and lipstick. This is apparent in the dissing of the humanities in academia — universities should rather be offering courses in producing and marketing lipstick and other cosmetics, rather than teaching useless stuff like history and literature.

And works for many of us born in the 1940s too

But this is perhaps where popular culture of the 1990s until now differs from from that of the 1950s, when the Narnia stories were written. People speak of generations like X and Y, and they have different cultures. I don’t know what letter my generation has, but it fell somewhere between the Beat Generation and the hippies.

There was popular culture, and there was the counterculture, which commercialised pop culture was always trying to coopt to make money out of it.

“Lifestyle” originally referred to a countercultural lifestyle, rejecting the dominant values of society. But it wasn’t long before the banks were advertising “lifestyle banking” with images of yachts, expensive cars and mansions — a Susan Pevensie lifestyle for the middle aged, perhaps. That was really grown up.

Last Thursday we had the opening parliament and the State of the Nation Address (SONA) amid cries of #PayBackTheMoney and #ZuptaMustFall. But just as impoerant, and demanding almost as many colum centimetres, was the fashion parade SUNDAY TIMES – From SONA to Zika: 10 things that happened this week you should know about

The State of the Nation Address may be focused on political topics but with every important event come important fashion moments. From Thuli Madonsela’s canary yellow gown to the long gold dress of Home Affairs Minister Malusi Gigaba’s wife, Noma, designer Gert-Johan Coetzee dominated the red carpet. Here are our best and worst looks from the night.

Back in the 1960s some of the countercultural Christians were called Jesus Freaks, but it wasn’t long before they were coopted by suit ‘n tie Christians, who were soon marketing a new line in plastic hippie Christian kitsch in the Christian bookshops.

I think I’ll stop there. If you want more, try Pilgrims of the Absolute by Brother Roger, CR.

February 9, 2016

The lamp of the wicked

The Lamp of the Wicked by Phil Rickman

The Lamp of the Wicked by Phil Rickman

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

I think I’ve read this book before, in fact I’m pretty certain I have, as many of the scenes rang bells for me, but the plot did not. Though there was so much that seemed familiar, i had no idea what was going to happen next, and so it was like reading the book for the first time. I had made no note of having read it before, so could not even tell when I had read it in relation to other books by Phil Rickman.

But whenever I read it before, reading it now makes me think that the book marks a turning point in Rickman’s novels, the point at which he switched from writing supernatural thrillers to writing whodunits. Being aware of what he wrote before and what he wrote after this book makes that clear, and as a result the book is rather jumbled and messy.

Merrily Watkins, for those who don’t know Rickman’s books, has taken over the job of diocesan exorcist for the Church of England Diocese of Hereford, but, since “exorcist” doesn’t fit with the modern image the church is trying to project, she is given the rather twee title of “Deliverance Consultant”, and is called in to deal with haunted houses and demonised individuals. She is also the Vicar of Ledwardine, a picturesque tourist village on the Welsh border, and single mother of a teenage daughter making the transition from New Age to atheism.

A parishioner, Gomer Parry, who runs a plant hire business, and features in even more of Rickman’s novels than Merrily Watkins, hears that his workshop has burned down, and suspects a business rival Roddy Lodge, whose shoddy workmanship Parry has criticised. But the discovery of a woman’s body excites Detective Inspector Frannie Bliss of the West Mercia police, who thinks he has a serial killer on his hands, an imitator, or even disciple of the infamous Fred West, serial killer of Gloucester.

The whiff of old evil brings Merrily’s mentor in deliverance ministry, the Revd Huw Owen, hot-footing it over the border from Wales, and all the while her boyfriend, Lol Robinson, a failed rock-folk musician, is making a reluctant come-back. To add a further complication a new parishioner at Ledwardine, Jenny Box, has seen a vision of an angel over the village, which inspired her to move there from London.

[Potential spoiler ahead]

This tangle of people with different aims and vested interests ends up in a spaghetti-like mess in the unlovely village of Underhowle, with a spectacularly botched funeral and an even more botched exorcism, with Merrily Watkins and Huw Owen working at cross purposes, in a series of scenes that are rather like a bad dream, where an important event is continually interrupted or sidetracked by a series of distracting happenings, and each interruption is itself interrupted by something else.

If I did read this book before, it didn’t look like a turning point, but reading it this time it now looks like the point at which Merrily Watkins makes the transition to becoming a 21st-century Miss Marple, only a bit younger and less astute.

Some of my other reviews of Phil Rickman books:

The remains of an altar

To dream of the dead

The secrets of pain

February 5, 2016

TGIF: reading irreligiously

This morning we went to TGIF to hear David Levey speak on Why I read irreligiously: doubt, apologetics and fiction.

TGIF (just in case you didn’t know, the letters stand for Thank God It’s Friday) is a weekly gathering in three different centres in Gauteng, held in bookshops with coffee bars attached.[1] Some one speaks on a topic usually related to the Christian faith and society and culture. It lasts an hour, from 6:30 am to 7:30 am, so people can get to work afterwards. We’ve been a few times, when people have spoken on topi9cs that particularly interested us.[2]

From the TGIF blurb:

What does literature have to say to theology – and vice versa? And how do we take literature on its own terms without hastily imposing theological categories; how do we leave room for and engage with doubts and genuine questions in literature? Don’t miss David Levey as he offers a tour of various authors ranging from postmodern writers to feminist theologians to new atheists. Drawing on his own journey of faith and reading, David will invite us to listen for the deeper questions.

This is part 1 of a 2-part mini-series. The first part will explore the relationship between theology and literature more generally, while part 2 (next week) will offer a particular focus on outspoken bestselling atheist Philip Pullman.

Prof David Levey has recently retired from the Dept of English Studies at Unisa but remains an Associate Professor and Research Fellow, with strong focuses on the faith-literature interrelation, especially as regards popular culture in general and Philip Pullman in particular.

We’ll have to go next week to hear the second part.

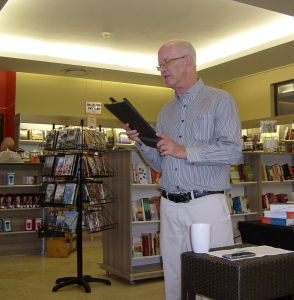

David Levey speaking at TGIF, 5 February 2016

Afterwards we discussed the possibility of meeting regularly to discuss the general topic of Christianity and Literature. TGIF is all well and good, but it covers a wide range of topics, not all of which are interesting to everyone. Perhaps what we want is a kind of Tshwane Inklings, with no speaker, no set agenda, just getting together to chat on the broad topic of Christianity and literature. Perhaps, like the Oxford Inklings of the 1930s, we may read some of our own writing to each other.

In order that it should not just be a vague desire, we set a time and a place for our first meeting: 10:30 am on Thursday 3 March 2016 at Cafe 41 in Eastwood Avenue, Arcadia, Pretoria, and thereafter on the first Thursday of every month. We will meet for coffee and literary/theological chat, and those who want to stay for lunch can do so.

If there’s anyone reading this who might like to participate, come and join us. If you live too far away, start your own, and join our electronic NeoInklings Forum, where you can discuss things online.

____________

[1] TGIF meets most Fridays at three different venues in Gauteng.

All venues start 06:15 am for 06:30 am and end 7:30 am sharp. Free entrance, all welcome. No need to book – just walk in.

The venues are:

Hodges Coffee House, 345 Jan Smuts Ave, CRAIGHALL PARK

Seattle Coffee Company, CRESTA Shopp’ng Centre

OM Link Building, 1211 South Street, HATFIELD

[2] You can read about some other TGIF gatherings we have attended here:

New monasticism meets old | Khanya

Hobbits, heroes and Jesus – TGIF | Khanya

Bloated job titles and other examples of diseased language | Notes from underground

February 4, 2016

Evangelicals and Evangelicalophobia

This is an election year in the USA and the media have been speculating on how “Evangelicals” will vote.

To judge from media reports the Evangelicals will vote either for Donald Trump or Ted Cruz. There have been some protests about this stereotyping of American Evangelicals, and I have written about the media stereotyping here. In some cases this has led to the phenomenon of Evangelicalophobia — fear and loathing of Evangelicals.

The phenomenon of Evangelicalophobia is not new, however. I became sharply aware of it in 1999 when the so-called Ontario Center for Religious Tolerance began promoting fear and loathing of Evangelicals. It turned out that their notion of “religious tolerance” did not extend to Evangelicals when in 1999 they began propagating rumours to the effect that Evangelicals, disappointed that the world had not ended in the year 2000, would stage terrorist attacks in the USA. These repeated warnings were clearly calculated to promote fear and loathing of Evangelicals, and seemed a pretty swivel-eyed notion of religious tolerance to me, and, in my view at least, completely undermined the credibility of the Centre.

So Evangelicalophobia had been around for some time, it didn’t just start with the current US election. But what is an Evangelical? This article So What, Then, Is “American Evangelicalism?” can help, and a British blogging friend, who lives in Cyprus and has experienced both British and American Evangelicalism, comments on some of the differences here: God-Word-Think: Evangelicals?

Perhaps people who want to know what evangelicalism is will find those helpful.

Part of the difficulty is that “evangelical” has a fairly wide range of meanings in Christian theology and history. It was originally an adjective, and its use as a noun is more recent. Here are some of the meanings.

Relating to the four written gospels of the New Testament. People sometimes speak of the “evangelical sacraments”, meaning baptism and the Eucharist, which are the only ones mentioned and also commanded in the Gospels. Others, like anointing of the sick (unction) are mentioned in the New Testament epistles, but not in the Gospels, so they are not “evangelical”.

The Evangelismos in an Orthodox Church, showing the Annunciation and the four Evangelists.

Pertaining to the Gospel or Good News of the Kingdom of God. Mark 1:1 The beginning of the gospel of Jesus Christ, the Son of God. The gospel (evangelion) is both the good news proclaimed by Jesus Christ, and the good news of his coming, which, according to St Luke, actually goes back a bit further, to the Annunciation (Evanglismos), the announcement of the angel to the virgin Mary of the coming of Jesus Christ. These events marking the coming of Jesus Christ have traditionally been celebrated by Christians annually on 25 March, 25 December and 6 January. One who proclaims the good news of Jesus Christ in speech or in writing is called an Evangelist. So the writers of the four written gospels are called Evangelists, and those who follow them in proclaiming the good news of Jesus Christ are called evangelists. Note that there is a difference between an evangelist and an evangelical, which at least some journalists are not aware of.

Protestant, and especially Lutheran Churches in Germany. Martin Luther disliked the term “Lutheran” and preferred “Evangelical”, indicating that he thought the Lutheran Church was truer to the gospel than the Roman Catholic Church. Therefore “Evangelical” can refer to Lutherans, as opposed to Roman Catholics or Calvinists (Reformed).

Among Anglicans, “Evangelical” meant “Low Church” rather than “High Church”. High Church Anglicans believed that the church was important, and that (in England) it was more than simply an arm of the State, but important in its own right. The Evangelical Revivals of the 18th century produced evangelistic preaching aimed at conversion or “awakening” of dormant nominal Christians, and this led to the interpretation of the term “born again” as meaning making a conscious decision to follow Jesus. This has sometimes been called “decisional regeneration”, to distinguish it from the traditional teaching of “baptismal regeneration”. With their emphasis on the importance of individual conversion rather than membership of the church, Anglican Evangelicals tended to be “Low Church”.

Evangelicals versus Ecumenicals. In the 19th century Protestant churches had become mission conscious, and sent missionaries all over the world to preach the gospel. In 1910 an International Missionary Conference was held in Edinburgh to discuss matters of common concern, one of which was that competition between the numerous different Protestant denominations from various countries was hindering mission. This gave rise to the Ecumenical Movement, which culminated in the formation of the World Council of Churches (WCC) in 1948. At a meeting of the International Missionary Council (IMC), which had been formed as a result of the Edinburgh conference in 1910, it was proposed that the IMC join the WCC, which happened in 1961, and the IMC became the WCC’s Commission for World Mission and Evangelism (see here for more details). Some Evangelicals objected, saying that this was making mission subordinate to the unity of the church. Thus there was a split between Ecumenicals, who saw unity as taking priority over evangelism, and Evangelicals, who saw evangelism as taking precedence over unity. The evangelicals arranged a series of mission conferences, now loosely referred to as the Lausanne Movement (from the venue where one of the conferences was held).

This is a very sketchy summary of some of the different meanings of “Evangelical”. Follow the links for more information.

Note that in the first two the word “evangelical” is an adjective, and these meanings are common to all Christians. In the last two “Evangelical” with a capital E is also used as a noun, and it refers to a subset of Western Protestants.

In this article I have made no reference to the rise of the “religious right”, which is a movement of right-wing political activism, which started among Fundamentalists rather than Evangelicals, but has extended its appeal to some groups of Evangelicals, especially in America. For more details see The Founding Father of the Religious Right. Before then, Evangelicals tended to be a-political. They were more interested in saving souls than in playing politics, and indeed one of their criticisms of Ecumenicals was that the latter were too concerned about politics. At Lausanne conferences there have been some differences of opinion between people with right-wing tendencies and the rest, but the right-wingers have generally been in the minority, and their views have not found much of a hearing. For more information see Documents of the Lausanne Movement.

For this reason I think the media stereotype of Evangelicals as right-wing in politics is inaccurate and unfair. Perhaps the word “Evangelical” has been skunked, and now means so many different things to different people that one needs to qualify it before using it. But I hope this article may bring a little clarity to those who have asked about it. And Evangelicalophobia, like Islamophobia, is an attempt to stir up religious hatred, and no good will come of it.

______________

Point of view of the author

Since I have said that “Evangelical” can mean so many things to different people, it may help anyone reading this to know where I am coming from.

I am not an Evangelical, but an Orthodox Christian, and so in a sense I don’t have a dog in this fight, and that gives me a measure of neutrality.

Having said that, I should also acknowledge that I might not have been Orthodox, or any kind of Christian at all had it not been for an evangelical teacher who evangelised me and rattled the cage of my atheist/agnostic upbringing to present to me the gospel of Jesus Christ. He was Steyn Krige, a conservative Evangelical and progressive educationist, a radical leftist of the religious right.

But I am not writing this to give an “Orthodox” view of Evangelicals and Evangelicalism. I’m writing it as a church historian and missiologist. I haven’t tried very much to “bracket out” my Orthodox views, since for the most part there has been little need — there has been little contact, and for the most part Orthodox and Protestant Evangelicals inhabit different worlds. But as a missiologist I do see at least one overlap: In the 18th century John Wesley and St Cosmas the Aetolian, quite independently, one in Britain and the other in the Balkans, went around preaching revival in the open air. John Wesley was one of the founding fathers of the Evangelical Movement.