Stephen Hayes's Blog, page 37

September 19, 2016

The problem of Susan: growing up?

A few months ago I blogged about “the problem of Susan” — a reference to C.S. Lewis’s book The Last Battle, the last of his series of Narnian stories.

David Levey had read a paper On reading irreligiously, in which he had mentioned that some irreligious critics of C.S. Lewis were hung up about “the problem of Susan”, one of six children who had previously visited the land of Narnia, but had lost interest in it as she grew up. The meme was perhaps expressed most strongly by J.K. Rowling (of Harry Potter fame), when she said:

David Levey had read a paper On reading irreligiously, in which he had mentioned that some irreligious critics of C.S. Lewis were hung up about “the problem of Susan”, one of six children who had previously visited the land of Narnia, but had lost interest in it as she grew up. The meme was perhaps expressed most strongly by J.K. Rowling (of Harry Potter fame), when she said:

There comes a point where Susan, who was the older girl, is lost to Narnia because she becomes interested in lipstick. She’s become irreligious basically because she found sex. I have a big problem with that.

David Levey mentioned this in his paper, though he was talking about Philip Pullman rather than Harry Potter, and you can see some of the background here and here. As Philip Pullman put it

And in The Last Battle, notoriously, there’s the turning away of Susan from the Stable (which stands for salvation) because “She’s interested in nothing nowadays except nylons and lipstick and invitations. She always was a jolly sight too keen on being grown-up.” In other words, Susan, like Cinderella, is undergoing a transition from one phase of her life to another. Lewis didn’t approve of that. He didn’t like women in general, or sexuality at all, at least at the stage in his life when he wrote the Narnia books. He was frightened and appalled at the notion of wanting to grow up. Susan, who did want to grow up, and who might have been the most interesting character in the whole cycle if she’d been allowed to, is a Cinderella in a story where the Ugly Sisters win.

These criticisms suggest that what C.S. Lewis was objecting to in Susan was that she had grown up, and did not remain an eternal child. But I am not alone in thinking that both Rowling and Pullman have seriously misinterpreted Lewis at this point. Because the problem was not that Susan was growing up, but that she wasn’t. ‘Grown up indeed,’ said the Lady Polly. ‘I wish she would grow up…’

And now someone has come up with the perfect illustration of the difference.

Susan’s idea of growing up is in the picture on the left, and the Lady Polly’s idea of growing up is in the picture in the right.

Susan’s idea of growing up is to be an airhead consumer; the Lady Polly contrasts this with becoming a thinking adult.

Susan’s idea of growing up is to be an airhead consumer; the Lady Polly contrasts this with becoming a thinking adult.

And the article at that site is worth a read too.

September 17, 2016

Spirituality in Orthodox Perspective: II | A vow of conversation

Macrina Walker notes in a blog post that “it is hardly surprising that some Orthodox theologians should be wary of the word “spirituality.” Golubov highlights the concerns of Father Stanley Harakas and Giorgios Mantzarides who reject the use of the word in an Orthodox context. Harakas argues that, in contrast to terms such as “spiritual life,” it has a “reified, objectified and ‘substance-like’ connotation” that he sees as related to western ideas about grace. He writes:

The parallel between ‘spirituality’ and grace understood as ‘created,’ an objective substance which is ‘conveyed’ by the sacraments, is too obvious to need documenting. It is no accident that a theological milieu accustomed to the understanding of divine grace as a created substance which was capable of being dispensed or withheld by the official Church, could in a quite analogous way, create the term ‘spirituality’ and live comfortably with it. (Kindle Location 120)

Source: Spirituality in Orthodox Perspective: II | A vow of conversation

I can heartily agree with that.

I’ve sometimes seen articles about words that get on people’s nerves, and I gather quite a lot of people have a strong aversion to the word “moist”. In the same way I have an aversion to the word “spirituality”.

I first became aware of it, and of my aversion to it, when I was a student at St Chad’s College in Durham, in 1966 or 1967. I, like many of the other students, was studying for a postgraduate diploma in theology. We had university lectures and college tutorials for the academic stuff, and then there were other gatherings in the grads’ common room for things like sermon practice. And one term there were weekly gatherings on “spirituality” — a lecture given by a member of staff, followed by questions and discussion. And it gave the the heebie-jeebies, like “moist” does for some people, because nobody bothered to define the word, it was simply assumed that we all knew what it meant.

They even had a session on Orthodox spirituality, which I wrote about in my diary.

Then went to the Junior Common Room, where there was a meeting of the Fellowship of St Alban and St Sergius — an introduction to the Eastern Church by Benedikz and Father Bates. Father Bates, it appears, spends his holidays in Greek monasteries. The thing lasted three hours, and was incredibly dull. However, their theme this year was “God and Caesar”, and they are having a conference on that theme in about six months time — so perhaps things might improve, or at least something fruitful may be learned at the cost of boredom. Father Bates, and the English generally, seem to find the Eastern Orthodox Church quaint, foreign, and rather amusing. They roared with laughter at the description of the way a priest baptised a child in St Oswald’s, and washed the olive oil off his hands in the font afterwards, and then got all deadly earnest and serious over obscure points of spirituality.

I was later to find that attitude quite common. English people affected an interest in Orthodoxy, but in fact they were only interested in Orthodox spirituality, whatever that was supposed to be, and from my observations their suppositions were pretty far removed from Orthodoxy itself.

Spirituality

And Father Hugh Bates (one of the college tutors) never did answer any of my questions about Orthodoxy, in spite of having spent time in Greek monasteries. In fact he discouraged me from asking, implying that it was something esoteric, dangerous, and definitely not for the hoi polloi like me, making it sound like a Rosicrucian ad for secret knowledge of the mysteries of the ancients.

The Fellowship of SS Alban and Sergius, which was supposed to promote understanding between Anglicans and Orthodox, began to look to me very much like what is nowadays called “cultural appropriation” — a selective nicking of bits and pieces of other people’s cultures, while ignoring or despising the rest. At least that’s what it looked like in Durham 50 years ago. It may have been different in other places, and it may be different in Durham today.

Spirituality seemed to be primarily a Roman Catholic word, adopted by High Church Anglicans, and seemed to be attached more and more to advertisements for retreats. I got a new insight into it about 10 or 15 years after my time at St Chad’s, from Colin Gardner, an English Professor at the University of Natal (now UKZN). He was a Roman Catholic, and this was at the height of the charismatic renewal. One of the leading figures in the charsimatic renewal in the Roman Catholic Church at that time was Cliff de Gersigny, a businessman and lay evangelist, who was off all over the place conducting missions, speaking in tongues, getting people to sing bouncy choruses and the like. He was fairly good at waking up somnolent parishes, and getting people to take their Christian faith more seriously. I mentioned him to Colin Gardner once, and Colin said that he was rather put off by Cliff de Gersigny’s “jaunty spirituality”.

Thinking of “jaunty spirituality” in relation to the Cliff de Gersigny I knew gave me a better understanding of the word, at least as Roman Catholics used it. It was also used in some Orthodox literature in English. I know of two different books called Orthodox Spirituality, one of them actually published by the Fellowship of SS Alban & Sergius, but neither of them dealt with the forbidden knowledge that Father Hugh Bates had so darkly hinted at. They just seemed to be dealing with how to live the Christian life. It then occurred to me that spiriuality was a rather poor attempt to translate the Russian word dushevnost, which might be better translated as “spiritual life” or “life in the Spirit”.

Either term seems better than the kind of moist spirituality people seem to talk about nowadays, which still gives me the heebie jeebies.

September 5, 2016

50 Years Ago: Verwoerd assassinated

Many people remember where they were when something momentous happens, like the assassination of Dr Verwoerd, and I happened, quite unusually at the time, to find myself in the company of South African expatriates in the UK, and the immediate reaction of all to the news was “Out of the frying pan and into the fire”.

I had a couple of days of from my job of driving buses for London Transport, and took the train from Waterloo to Bournemouth to stay with Arthur and Florence Blaxall.Arthur Blaxall was an Anglican priest who had worked among deaf and blind children. He was also a pacifist, and ran the office of the Fellowship of Reconciliation in Johannesburg. He had been arrested and charged under the Suppression of Communism Act for things like supplying spectacles to members of the families of political detainees, given a suspended sentence, and forced to leave the country, so he was an exile rather than an expatriate.

I had a couple of days of from my job of driving buses for London Transport, and took the train from Waterloo to Bournemouth to stay with Arthur and Florence Blaxall.Arthur Blaxall was an Anglican priest who had worked among deaf and blind children. He was also a pacifist, and ran the office of the Fellowship of Reconciliation in Johannesburg. He had been arrested and charged under the Suppression of Communism Act for things like supplying spectacles to members of the families of political detainees, given a suspended sentence, and forced to leave the country, so he was an exile rather than an expatriate.

I got to Waterloo station about 10:10, and had breakfast there, There was rather sickly music gurgling from loudspeakers all round the platforms. The place where I had breakfast was called “The Windsor Room”, with rather pretentious decorations, and cheap furniture that made the total effect rather ridiculous. I had meant to get the 10:30 train, but on getting on to the platform found it was full up. I went to the end of the platform and watched it pull out — it had a steam locomotive at its head — the first I had seen in England. Like the rest of the British Railways rolling stock, it had these great big spring-loaded buffers at each end and no cow catcher, which gave it a sort of Hornby toy appearance. Then I went back to the concourse again and bought a book, which I read at the platform gate while waiting for the next train at 1:30. It was called Mandrake — about a British minister of planning who gets an idea similar to Dr Verwoerd’s Bantu Homelands — traffic is diverted from the towns, and people are moved around and sent to where they were born, and the earth takes revenge on them.

I got to Waterloo station about 10:10, and had breakfast there, There was rather sickly music gurgling from loudspeakers all round the platforms. The place where I had breakfast was called “The Windsor Room”, with rather pretentious decorations, and cheap furniture that made the total effect rather ridiculous. I had meant to get the 10:30 train, but on getting on to the platform found it was full up. I went to the end of the platform and watched it pull out — it had a steam locomotive at its head — the first I had seen in England. Like the rest of the British Railways rolling stock, it had these great big spring-loaded buffers at each end and no cow catcher, which gave it a sort of Hornby toy appearance. Then I went back to the concourse again and bought a book, which I read at the platform gate while waiting for the next train at 1:30. It was called Mandrake — about a British minister of planning who gets an idea similar to Dr Verwoerd’s Bantu Homelands — traffic is diverted from the towns, and people are moved around and sent to where they were born, and the earth takes revenge on them.

The train got to Bournemouth at about 2:30, and I went out of the station and got a number 4 bus to the terminus, as instructed by Arthur Blaxall. I was rather disappointed that it was not a trolley bus, and when I got to the terminus I found an old trolley bus route had come up there once, but now all the wires had been taken down, and just the poles left standing. I saw the tower of the church, and made for that, and reached it about 10 to 3. And is there honey still for tea?

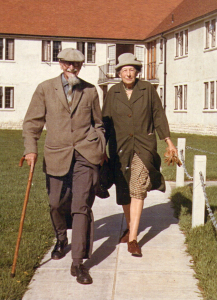

Bournemouth, September 1966

Alverna House, where Arthur and Florence Blaxall were staying, was quite a new place, built next to the church, for retired clergy, or those in England on holiday. It is run by the United Society for the Propagation of the Gospel (USPG). I was showing Arthur some photographs when a priest, also from South Africa, Michael McKay, who came from somewhere in the Cape, burst in and announced that Dr Verwoerd had just been stabbed in parliament. “This is terrible,” Florence

said. “Vorster takes over,” I said. Father McKay could give no details of who had done it — he had been in a shop to buy a record when the announcement was made over the radio in the shop. Florence said there were usually news headlines on the BBC light programme at 3:30, so we waited for that, talking and wondering what would happen now. I had had a letter from John Aitchison a couple of days ago with the good news that banning orders of Elliot Mngadi and Mike Ndlovu (two Liberal Party organisers) had been lifted. I had just shown it to Arthur and said I agreed with John that the ardent Nats and even Dr Verwoerd were becoming a little apprehensive about the growing strength of the right-wing fascist element, led by Vorster, and perhaps Vorster had been rapped on the knuckles over the banning of Ian Robertson, a rather mild student leader, and we wondered if this assassination might be Vorster’s revenge. The thing that concerned us all was that Vorster, the leader of the hard right of the National Party, would now take over.

Arthur told us stories of Verwoerd when he was priest in charge of Heidelberg, Verwoerd’s constituency. He was not, said Arthur, very popular there. On one occasion he had been asked to officially open the national road by-pass, and there had only been the mayor and a couple of the town councillors and Arthur and Florence there. The rest of the population stayed behind at home, not interested. On another occasion there had been a National Party stryddag, and they had bought large quantities of meat for a braaivleis, but the meat had to be given away afterwards because it was so poorly attended. He also said that on the occasion that Verwoerd was shot at the Rand Show, the news was flashed on the screens at the bioscopes, and at the non-European one in Market or Commissioner Street, there was a huge cheer. When it was announced that he was expected to recover there was an equally huge groan.

Arthur and Florence Blaxall at Alverna House in Bournemouth, 6 September 1966

I remembered the occasion well. It was the Saturday before Palm Sunday, and I was with the rest of the AYPA — the youth group at St Augustine’s Anglican Church in Orange Grove, Johannesburg. We were making palm crosses for use in church the next day. When someone announced the news that Verwoerd had been shot there was a spontaneous cheer from everyone — then disbelief. We cheered then because the Sharpeville massacre was still fresh in the minds of all of us, with the State of Emergency and the banning of the African National Congress and the Pan African Congress. It was a release, and the first impulse was to cheer. But not so six years later, because there was only the knowledge that Vorster was waiting in the wings.

We went to town then, by trolley bus. Stood in a queue with hordes of children, and had to stand on the bus when it came. The schools seem to have re-opened today. The bus was a yellow-painted Sunbeam MS2B, with front overhang, and two staircases. It seemed to go very well; indeed it was a joy to ride n a trolley bus again, and some of the streets we passed through might have been in Durban or Pretoria — wide, straight tree-lined avenues, with houses set back from the road and separate from each other. Arthur pointed out a school where people from all over the world came to learn to speak

English. It stretched quite a way along the street, and then the yellow bus nose-dived down a steep hill, and we got out.

We walked through some gardens, with hundreds of people wandering around, all pink, as Englishmen seemed to look when they have been in the sun. A stream, the Bourne, ran through the middle of the gardens, with children paddling and lots of old men with military moustaches wandering about. There was also a bandstand, but the band was not playing at the moment. Then we came to the beachfront, which looked like East London, and there was a paper seller with the evening news, and the placard screaming about Verwoerd being murdered. We bought one, but there appeared to be nothing in it — and so I asked the paper seller if it was the one with the news about Verwoerd. It’s in the stop press, he said with the news about Verwoerd. It’s in the stop press, he said irritably, and went on to mutter something about having been in the place 28 years. Over the way another bloke was selling the local paper, the “Evening Echo”, and that had a more informative article, and an ironic stop press — “Verwoerd dead — official”, and underneath “No Justice” in the racing news. At 2:30 No Justice won the race, and Verwoerd was wheeled out on to the ambulance.We thought it was prophetic. There would be no justice when Vorster took over.

We walked through some gardens, with hundreds of people wandering around, all pink, as Englishmen seemed to look when they have been in the sun. A stream, the Bourne, ran through the middle of the gardens, with children paddling and lots of old men with military moustaches wandering about. There was also a bandstand, but the band was not playing at the moment. Then we came to the beachfront, which looked like East London, and there was a paper seller with the evening news, and the placard screaming about Verwoerd being murdered. We bought one, but there appeared to be nothing in it — and so I asked the paper seller if it was the one with the news about Verwoerd. It’s in the stop press, he said with the news about Verwoerd. It’s in the stop press, he said irritably, and went on to mutter something about having been in the place 28 years. Over the way another bloke was selling the local paper, the “Evening Echo”, and that had a more informative article, and an ironic stop press — “Verwoerd dead — official”, and underneath “No Justice” in the racing news. At 2:30 No Justice won the race, and Verwoerd was wheeled out on to the ambulance.We thought it was prophetic. There would be no justice when Vorster took over.

Revd Arthur Blaxall, 6 September 1966, on Bournemouth Beach

We walked along the beach front and sat in deck chairs and read the papers, and discussed some more. It was now just after 5:00, but the sun was still bright as we sat watching the sea with the rather treacherous-looking waves and the stony beach. There were few swimming here, and it was not surprising as there seemed to be a steeply sloping beach, and a strong undertow. A woman plonked down next to Florence, and listened in on our conversation, then said to Florence, “Did you hear about Dr Verwoerd?” “Yes, shocking, isn’t it.” A man came around to collect money for the chairs we were sitting in, and I paid him.

We sat there in the sun for quite a while chatting and looking at the sea. It was the end of an English summer, and so there was a hint of autumn in the air. But our thoughts were far away, back home in South Africa where it was the beginning of spring and I could picture the azaleas blooming in Pietermaritzburg, but politically there was a chill in the air there too, with the prospect of Vorster having unrestrained power. Verwoerd was the architect of apartheid, but Vorster was the architect of the South African police state.

Florence Blaxall 6 September 1966, Bournemouth Beach

About nine months earlier I had heard Verwoerd speaking at a meeting in the Pietermaritzburg City Hall. Three years earlier had had spoken there and he had had to be brought into town by a back route, to avoid student demonstrators on the main road. And when he got to the hall the stage was booby-trapped, and bags of flour rained on him and others on the podium. That was just after South Africa had become a republic, and much of the ire against him came from British Empire Loyalists, though the students demonstrated against apartheid.

In 1965, however, the Empire Loyalists had become renegades along with Ian Smith, whose UDI for Rhodesia had made headlines the day before. So Verwoerd was given a hero’s welcome by the “kith and kin” crowd, and the international media were there in force to hear what he had to say about UDI. Instead they had to listen to him speaking for two and a half hours about Sir de Villiers Graaff and the United Party. He dismissed UDI in one or two sentences: our policy is well known, he said, we do not interfere in other people’s domestic affairs.

We left the beach and rode up to the top of the hill in a funicular. The last time I has been in one one must have been when I was about 6, at Brighton Beach, near Isipingo, but it had closed long ago. I wonder if the Bournemouth funicilar is still operating 50 years later. From the top there was quite a good view over the beach, and we walked down again to the gardens.

Bournemouth, September 1966

I bought another, later edition of the Echo, which had a fuller report of the assassination splashed on the front page. “Dr Verwoerd assassinated in parliament” “Stabbed by white” it announced. The man who did it was said to be a parliamentary messenger, of Greek descent.

We got a bus home from the beach a number 1, a single decker with plush seats and headrests and all, to Kings Road, where we got a trolley bus the rest of the way.

We got a bus home from the beach a number 1, a single decker with plush seats and headrests and all, to Kings Road, where we got a trolley bus the rest of the way.

When we got back to Alverna House in came a chap called Arnold Hirst, priest, also from South Africa. He was from Stellenbosch, where he had just done his curacy under Canon Findley. He was stocky, thickset, smoking a pipe, with blond hair. Very much a white South African. He was quite upset by the news of the assassination — said he could just imagine the effect it would have on his parish — it seemed that hordes of them were scuttling over to support the Nats. “Hell’s delight!”, he said, and so it would be, I thought, with Vorster on the loose and unrestrained. I was to meet Atnold Hirst again six years later, in 1972, when he was rector of St Martin-in-the-Fields Anglican Church in Durban North. I was banned to Durban and had nowhere to live there, so he put me up for a few days until I could find somewhere more permanent to stay, and 18 months later invited me to join him in the parish.

We had supper, and then went upstairs, where there were two old ladies, Dr Christie and another, who were retired missionaries from India. We watched the 10 to 9 news on their television, which was mostly about the assassination, and showed pictures of Verwoerd being carried out on a stretcher. It also showed reactions of people interviewed outside South Africa House

in London; a woman who was a devoted admirer, overwrought with emotion. The men were generally against Verwoerd, but also against the assassination, except for an African who said he was overjoyed, and that it was the happiest day of his life, and wished he had done it himself. Perhaps he is not a South African, or if he is does not intend to go back there, because for those at home there is little cause for jubilation. It will be out of the frying pan, into the fire, with little doubt.

At 10:20 pm we went up again to see the 24 hours programme, which was very good, including interviews with Joe Matthews and Bloke Modisane, and also a guy from the SABC, who made no secret of South Africa’s intention to take over the protectorates. We wondered if Leabua Jonathan (Prime Minister of Lesotho) and Verwoerd had discussed plans for the Anschluss when they met the previous week, and perhaps that was what Oom Henk was about to speak about when he was killed. Now we shall never know — at least not from his lips. There was also a slimy gent from the South African Foundation — a slimy businessman, who obviously didn’t care how many people were in jail, as long as his business keeps booming.

I hadn’t gone to Bournemouth to talk about the assassination of Dr Verwoerd, however, but rather to spend some time with Arthur and Florence Blaxall, and this blog post is really about them. The assassination just happened to be the main topic of conversation that day. Arthur Blaxall was my mentor in Christian pacifism, and I hope one day someone will write his story. Perhaps this can be a small contribution towards it.

September 4, 2016

Click Bait in the Age of the Feuilleton

The Glass Bead Game by Hermann Hesse

The Glass Bead Game by Hermann Hesse

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

This is a strange book. Written in the 1930s, it is set in the future, and in that it is similar to Brave New World by Aldous Huxley, which somehow seems to invite comparison. And there are comparisons, though these two eighty-year-old visions of the future are also very different. But both describe a hierarchical society. Huxley’s book has a reservation for savages, those who do not fit in to the highly organised society of the civilised, where consumerism is taught from infancy.

In The Glass Bead Game, however, the reservation is not for savages, but for intellectuals, who live in the province of Castalia, where they are free to engage in their intellectual pursuits, untroubled by the world outside. It is an all-male society of elite schools whose students are picked by the elite.

The main part of the book is the story of one of these elite students, Joseph Knecht, who rises through the ranks to become the Master of the epitome of Castalian society, the Glass Bead Game. The book begins with a history of the Glass Bead Game, which explains nothing about the game itself — how it is played, or how one wins or loses.

Hesse tells us very little about this society and how it functions. There is virtually no mention of the technology of the 23rd century. There are virtually no female characters and those few who do appear (outside Castalia) are virtually characterless.

But I did learn a new word: feuilleton.

The denizens of Castalia refer to our age (or rather Hesse’s age), the age of the 1930s and 1940s, as the Age of the Feuilleton, or the Age of Wars.

I had to look it up, and it seems that a feuilleton is a section of a newspaper devoted to feature articles and op-ed pieces, shallow journalistic renderings of what is happening in the world. It struck me that if Hesse thought that the 1930s and 1940s were the Age of the Feuilleton, our time must the Age of the Feuilleton on steroids, because back then he was thinking purely of print media — newspapers and magazines. He did not envisage the Web, but I think perhaps the best way to describe the Age of the Feuilleton in today’s terms would be Age of Click Bait — the endless pursuit of trivial knowledge, trivially presented. And perhaps I’m a good representative of that age, because the only TV programme I watch with any regularity is the quiz show Pointless, which deals with exactly that.

But in the absence of any description of the material culture of the post-Feuilleton age, what one might call the Glass Bead Game Age, I had to fall back on the 1930s vision of the future, and pictured Joseph Knecht’s schools as being built in the Bauhaus style.

But in the absence of any description of the material culture of the post-Feuilleton age, what one might call the Glass Bead Game Age, I had to fall back on the 1930s vision of the future, and pictured Joseph Knecht’s schools as being built in the Bauhaus style.

In the course of his schooling Joseph Knecht meets a fellow student from the outside world beyond Castalia, a world to which he returns for his holidays, and he alone is critical of Castalian society and its values. He points out that there is nothing creative about it. They study creations of people of the past, art, music and science, without studying the past itself which produced them. Joseph Knecht alone has an interest in history, to the study of which he was introduced during a visit to a Benedictine monastery.

At the end of the book are some poems and three short stories, said to have been written by Joseph Knecht himself. And the three short stories are better than the entire book.

I nearly didn’t read the three short stories. I thought the book was long, and I carried on reading because I wanted to see what happened, but I tired of the two-dimensional description of a two-dimensional world. Yet the short stories are in fact an essential part of the book, and are the key to understanding the rest of the story.

And one excerpt from one of the short stories at the end seems to say a great deal about our age, and the religion of our age, and especially about Christianity in our age, with Christian leaders like T.B. Joshua and the writers of what a friend of mine called “spiritual Westerns”. It seems to sum up much of my experience of Christian ministry.

These are matters which in the several thousand years since his era have probably not changed so much as a good many history books claim. But he had also learned that a seeking, thoughtful man dare not forfeit love; that he must meet the wishes and follies of men halfway, not showing arrogance, but also not truckling to them; that it is always only a single step from sage to charlatan, from priest to mountebank, from helpful brother to parasitic drone, and that the people would by far prefer to pay a swindler and be exploited by a quack than accept help given freely and unselfishly. They would much rather pay in money and in goods than in trust and in love. They cheat one another and expect to be cheated themselves. You had to learn to see man as a weak, cowardly and selfish creature; you also had to learn how many of those evil traits and impulses you shared yourself; and nevertheless you allowed yourself to believe, and nourished yourself on the faith that man is also spirit and love, that something dwells in him which is at variance with his instincts and longs to refine them.

September 1, 2016

Spring, eclipse, books and more

Happy Spring Day and Happy New Year! Welcome to the new year 7525.

We had our Literary Coffee Klatsch at Cafe 41 in Eastwood Road, and to celebrate Spring Day there was also a partial eclipse of the sun, which we kept popping up to look at.

Pete Beukes checking on the solar eclipse

The eclipse was only partial where we were, but in some places people could see a full annular eclipse, where the disc of the sun could be seen all the way round the moon.

We tried the Greek coffee this time, but it somehow looked Turkish.

Greek (or is it Turkish?) coffee at Cafe 41

We chatted about many things, but the book part of our discussion was mainly about the role of books and stories in education.

Isobel Beukes told of training teachers in using stories in teaching. Trainee teachers were given children’s stories to read, and asked to explain how they could use them in teaching.

That reminded me of something that had been suggested by Father (now Bishop) Athanasius Akunda, when we were involved in a somewhat pemature attempt to start an Orthodox theological seminary in South Africa. We thought it would be better to start a kind fo pre-seminary school, where potential seminary students could have some preparatory training. Fr Athanasius suggested that one could teach theology through literature, and we tried it out in one of our classes.

We asked advice from people about what books could be used, and one of the suggestions made by the late Fr Thomas Hopko of St Vladimir’s Seminary in New York, was to use short stories by people like Chekhov, and in particular he mentioned “The Bishop” . So we asked the students to read Chekhov’s story, and also the story of the Martyrdom of Polycarp — the death of two bishops in different times and places, different cultures, different expectations, and to note the similarities and differences, and see what they could learn from the stories about what a bishop was.

Literary Coffee Klatsch: Val Hayes, Pete and Isobel Beukes

Isobel’s story about children’s books also reminded me of a time I was asked to teach religion classes in school. It was St Paul’s Catholic School in Windhoek, and they asked me to teach the non-Catholic students. Teaching children, however, is not my thing. So I read to them from C.S. Lewis’s Narnia stories, and asked them to discuss the stories. These were children of 9-10 years old, and with such an age group I’ve been quite happy to acts as a consultant and advisor on how to run a youth group, but the “teacher-tell” thing is not for me, at least not with that age group. In a classroom situation the children are inhibited and reluctant to discuss things. The atmosphere of a youth group, with no teacher as an authority figure, is much less inhibiting.

August 26, 2016

The Singularity as a plural

Twice in the last month I’ve heard people speaking on and expounding ideas that were familiar to me, and yet presented in an unfamiliar way.

This morning it was Izak Potgieter speaking on The Singularity, and a fortnight ago it was Jan Kleinsmit speaking about the Sons og God in the Old Testament. What struck me as singular (sorry!) about both was that both speakers relied on a single book by a single author for the ideas they expounded, and presented these ideas as new and, if not unique, at least highly unusual. And though I had been familiar with the ideas for 50 years or more, I had not read, or even heard of, either author or book.And neither speaker seemed to have read or even heard of any of the books that I had read that had made me familiar with those ideas.

Toppies in the aloes outside the windows at TGIF

These ideas were presented at TGIF — a weekly gathering at which someone presents a paper on some aspect of the Christian faith or something in culture or society that is relevant to it, and there is brief discussion afterwards. It’s held early in the morning so people who have to work can get to work in time. I’ve been going to it on and off for the last 10 years or so, mainly when the topic is one that interests me. I find it useful because since I retired from the University of South Africa there have not been many opportunities for intellectual stimulation and discussion. For a while it was possible to do it in internet mailing lists and newsgroups, but people seem to have been abandoning those forums for social networking sites like Twitter and Facebook, where the exchanges become more trivial and random as time passes.

So I was quite interested to attend these gatherings, and feel like a dinosaur from the prehistoric world, where people were reading and discussing books I had never heard of, and they had never heard of the books on the same topics that I had read.

More toppies at TGIF

Izak Potgieter referred to a book called The Singularity is near by Ray Kurzwell. At the end of it I still wasn’t clear about what constitutes the singularity he was talking about. He referred to the rate of technological change and developments in artificial intelligence, topics that had been dealt with 30-40 years ago by Alvin Toffler in his books Future shock and The third wave. Coincidentally I had blogged on the topics of consciousness and artificial intelligence only a couple of days before (see Networking and consciousness), and though I did not mention it in the blog post, one of the essential features of the story I took as the starting point was the question of singularities in the topology of networks. I gather that in the story the concept of a singularity has been somewhat oversimplified and is not mathematically accurate, but at least when I had read the story I had some idea of what a singularity is, while I still have no idea of Ray Kurzwell’s concept of a singularity.

Jan Kleinsmit’s topic, of the Sons of God in the Old Testament, deserves at least a blog post, if not a monograph on its own. At one time I was toying with the idea of writing a book on the topic and had got a few rough drafts written, but then a bloke called Walter Wink beat me to it, so I gave that up. But the bare bones of the idea were laid out by G.B. Caird in his book Principalities and Powers, which was published 60 years ago, and were hinted at in the novels of C.S. Lewis and Charles Williams, and of course go back to St Paul himself, and mediated through Dionysius the Areopagite and others.

August 18, 2016

War and peace

Captain Corelli’s Mandolin by Louis de Bernières

Captain Corelli’s Mandolin by Louis de Bernières

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

When this book first appeared in bookshops about 20 years ago I picked it up, read the blurb, and put it down again. One day perhaps I’ll read it, but not yet, I thought.

Then I bought a book called The Modern Library (see What should I read next? | Khanya) and it recommended [book Captain Corelli’s mandolin] as one of the best books published ion the second half of the 20th century. So when I fund it in the public library, I thought it was time to read it. And having read it, I’m very glad I did.

Do I regret not reading it at the time?

No, because when I first saw it in the shops I had not been to Greece. I had read a similar book about Greece in the Second World War, Eleni by Nicholas Gage, but that was non-fiction, as was about the author’s search for the stories of his forebears in north-western Greece. I took it out of the library again when we were about to visit the area.

I’m sure that Captain Corelli’s mandolin is a very good read whether one has visited Greece or not, but having been there, it helps to understand it better.

It is a story of war and peace, hardship and prosperity, and what war does to people and societies. The characters are memorable, the descriptions of both joys and sorrows are vivid. If you read this book, it will give you some idea of what war-torn societies like Syria are going through right now, and what the refugees are fleeing from, and what it feels like to be betrayed by the great powers fighting proxy wars in your home country.

August 11, 2016

What should I read next?

The Modern Library: The Two Hundred Best Novels in English Since 1950. Carmen Callil and Colm T[ibn by Carmen Callil

The Modern Library: The Two Hundred Best Novels in English Since 1950. Carmen Callil and Colm T[ibn by Carmen Callil

In 2013 we spent R2952.83 on books, including this one at R167. In 2012 we spent R3940.40 on books, and in 2011 R2019.95. But when Val retired in 2014, we could not afford to go browsing in bookshops and just buying whatever took our fancy, so we rejoined the public library.

In 2014 our spending on books dropped to R1653.50, and in 2015 to R50.01. But browsing in a library is not the same as browsing in a bookshop. In a bookshop, the popular books will be stocking the shelves. In a library, the popular books will probably have been taken out by others.

That is where books like this come in. OK, it’s someone else’s choice, and their taste may not coincide with yours, but you at least know that some book lovers think it is worth reading. And, to back it up, at the back of the book are some lists of winners of some of the major literary prizes. And if you don’t find the book in question, another one by the same author might be worth a read.

The authors’ list has descriptions of each book and why they think it is worth reading, so from those I’ve compiled a list, which I take to the library, at least when I remember to.

One of the bloggers on my blogroll, A Pilgrim in Narnia | a journey through the imaginative worlds of C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, and the Inklings, says:

I am a list-driven reader. I like logging my works on Goodreads, and use an excel sheet to keep track of the books and essays I read. My bulletin board has certain lists I’m going through: top 20th c. SF books, top 20th c. Fantasy books, Discworld, Harold Bloom’s Essential List, a World Fantasy Conference List, everything C.S. Lewis wrote, and a list of key Christian books. I am slowly going through these lists, book by book, and hope to be done around 2030 or so, provided no one writes anything good between now and then.

I wouldn’t go as far as to say that I am a list-driven reader, but I do try to make lists of books I’ve bought and books I’ve read, and more so in recent years.

When I was at school my mother used to work for a firm of estate agents and auctioneers, and when she wasn’t busy she used to look at some of the auction lots, which sometimes contained bundles of books from deceased estates, and quite a lot of our books were obtained that way. One of the books she bought was The Booklover’s Record, with the inscription, “To M Norenda, with love from Minnie, 1938”. My mother give it to me, and I added the date I acquired it, 5 January 1956 — I was 14 at the time. It had eight tabbed sections for writing in:

Books recommended

Notes about books read

Books borrowed

Quotations from books

Books lent

Extracts from criticisms

Authors and Publishers

Sundries

I’ve now made many of those sections into fields in a database, in which we’ve tried to record books in our library, books we’ve borrowed from other people and libraries, books we’ve read or want to read, and so on. Like Brenton Dickieson I’ve tried to record some of them on Goodreads, particularly ones that I think friends may be interested in, but most I try to record in the database, and have transferred most of the ones I initially recorded in A Booklover’s Record. There are, of course, some books that the original owner read or had recommended.

In July 1938, for example, the original owner noted having read Insanity fair by Douglas Reed, with the note “Douglas Reed is a depressing ‘European situation’ writer.” Insanity fair is on our shelves too, though a 1939 reprint, and I read it in 2002.

Before computers were available I used to note some books I had bought and read in my diary, with comments on them, and some of those I have also transferred to the database — that doesn’t work too well with GoodReads, which is mostly for current reading. Even with such lists, however, we’ve still occasionally bought books and got home to find we already had a copy. But between the book list and my journal, I can usually check on when I read a book, and sometimes who recommended it to me.

August 10, 2016

The cult of Rhodes

The Cult of Rhodes: Remembering an Imperialist in Africa by Paul Maylam

The Cult of Rhodes: Remembering an Imperialist in Africa by Paul Maylam

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

Why am I reading this book?

Because of the “Rhodes must fall” movement, which began with the demand for the removal of a statue of Cecil J. Rhodes from the campus of the University of Cape Town.

Because of the rise of Donald Trump in US politics. Cecil Rhodes seems to have been the Donald Trump of his day, an unscupulous businessman turned politician.

Because of family history. At least one member our family, Henry Green, went to Kimberley at the time of the diamond rush, and some of his children were either associates or admirers of C.J. Rhodea and Company, and gave names to their chuildren that reflected this – one child, for example, was named Cecil Leander, and, like his namesakes, he never married.

Protests against Rhodes statues at the University of Cape Town

Concerning the first of these. it is mainly curiosity. I don’t feel particularly strongly about statues of dead politicians, good or bad. Getting uptight about them seems rather pointless to me, and itmight be better to pay more attention to living politicians, who can do real damage, and more rarely, some good. About 20 years ago I was wandering through a park in Klin, in Russia, and there was a statue of Lenin. I suppose on the whole I’d prefer that it not be removed, but should stay as a reminder of history.

The resemblance to Donald Trump is more interesting, because Trump is a living politician who, like Rhodes, seems to have a cult following. According to Paul Maylam the cult of Rhodes seems to have arisen mainly after his death, fostered by his close associates who wrote biographies, and his will, which provided for various things by which he would be remembered, most notably the Rhodes Scholaships. Rhodes’s funeral, too, which was a long drawn-out affair, seems to have been calculated to foster the cult. Trump, on the other hand, seems to have a cult following even while he lives, though it may die down if he fails to be elected as president of the USA in November, and cause him to be no more remembered than Tielman Roos.

I was interested to learn how Rhodes University in the Eastern Cape (a part of the world that Cecil John Rhodes had little to do with) got its name. It appears that they were hoping to get sponsorship from the Rhodes Trust, and thought that calling it Rhodes University would increase their chances. Now that’s like certain sports reports I see on TV, when they say that a certain football team in the English Premier League has been “playing at the Emirates”. I pictured them having a six-hour flight to and from the Gulf, and think they must be pretty exhausted with all that travelling. But no, the stadium is in London, and sponsored by the Emirates airline. So if Rhodes University changes its name and suddenly becomes Nandos University, you’ll know why. The name of the university has little to do with the cult of Rhodes, and everything to do with sponsorship, marketing and branding.

The cult of Rhodes went way beyond the man himself, and was particularly strong in Southern Rhodesia, and Northern Rhodesia, the countries named after Rhodes, which jettisoned his name as soon as they became independent. Some white people in those countries named their children after Rhodes, even though they had no personal connection with him. But this also raises questions that Maylam does not deal with in the book. Rhodesia was conquered by Rhodes’s British South Africa Company under a royal charter, and the company ruled until 1923, when Southern Rhodesia became a self-governing British colony, and Northern Rhodesia became a protectorate. It would be interesting to know whether and how the cult of Rhodes differed before and after this event, but Maylam does not tell us. Another weakness of the book is its repetitiveness. Maylam reiterates the same points in every chapter.

Though Paul Maylam does not admire Rhodes, and disapproves of the cult, his book supports the cult in a curious way, by punctuation. He uses “Rhodes'” for the possessive rather than “Rhodes’s”. In English that form is only used for revered figures from the ancient world — Jesus, Moses, Socrates and so on. Maylam tells us that Rhodes admired classical civilisation, and liked to be identified with it, and his friend and admirer Sir Herbert Baker designed his memorial along classical lines for that reason, and every time I came across the possessive “Rhodes'” in the text I stopped short, and the cult came to the fore. Rhodes would have liked that.

Not all of his contemporaries admired Rhodes, and both his admirers and detractors compare him with other historical figures. As Maylam puts it,

Rhodes has been compared to many other historical figures — Caesar, Napoleon, Cromweell and Bismarck. to name just a few — but, as far as I know, he has never been compared to Shaka, the Zulu king. This would seem an unlikely comparison, and in many respects, it is. But it is not so much their lives that bear comparison, but their legacies and the way in which they have been represented and remembered. Both have come to be viewed in a polarised way, as hero or villain. Shaka has been represented as the heroic nation-builder, but also as a brutal tyrant; Rhodes as the great empire-builder, but also as the ruthles, dictatorial imperialist. Shaka has been revered by African nationalists, but hated by most white colonialists — although some of them have shown a grudging admiration for the Zulu king as a “noble savage”. Rhodes has been revered by imperialists, but loathed by African nationalists — although again there is evidence that some African leaders, especially in the early twentieth centuiry, admired Rhodes as “a great man”.

Some have also compared Rhodes with Robert Mugabe, and Maylam remarks, “Both men can be characterised as arrogant, authoritarian and vain. Both were land grabbers. And both were content to use force and violence to achieve their political ends.”

Maylam also makes much of the resemblance of the Rhodes memorial in Cape Town to a pagan temple,

… the colossal bust of Rhodes portrays him as a great thinker — which he was not. He had ideas, certainly, but as some biographers have observed, they were often boyish and immature… locating the bust in a “temple” amounts to the deification of Rhodes — but Rhodes, although the son of an Anglican clergyman, was not a religious person. For many, the near deification of someone who was far from being saintly smacks of idolatry.

Cecil Rhodes Memorial in Cape Town. By SkyPixels – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=40468097

G.K. Chesterton, writing in 1912, said,

Rhodes had no principles whatever to give to the world. He had only a hasty but elaborate machinery for spreading the principles that he hadn’t got. What he called his ideals were the dregs of a Darwinism which had already grown not only stagnant but poisonous. That the fittest must survive and that ony one like himself must be the fittest; that the weakest must go to the wall, and that anyone he could not understand must be the weakest.

And perhaps that fits Donald Trump as well.

August 7, 2016

The funeral of Philip Mabena

Philip Mabena died on 26 July 2016. He was a member of the African Orthodox Church (AOC) in Atteridgeville, whose church building we have been renting for our services since the beginning of this year. We have had a long association with the African Orthodox Church in Atteridgeville, as we first visited them in 1989, and their priest at that time, Johannes Motau, sometimes attended Orthodox study groups, and also some services at the Church of St Nicholas of Japan, then meeting in borrowed premises in Yeoville, Johannesburg.

Philip Mabena was one of the leading members of the AOC in Atteridgeville, and was, in a way, the glue that held it together, so though we did not know him well, we have known him for a long time, and so we all went to his funeral. He was a retired policeman, and had been born on 1 July 1932, which surprised me, as I thought he was much younger than that.

I write about his funeral not merely because of who he was, but because, as far as I can determine, the Orthodox Church in South Africa has given very little thought to death and its rituals in southern Africa. Of course the Church has its service books and their rubrics, but many of these are impractical in the circumstances in which Orthodox Christians find themselves here. I have attended many funerals, and served at some, and my observation is that funeral customs vary from place to place and from time to time, and are largely determined by burial societies and funeral directors.

I have sometimes asked about customs that were new to me, and the usual response has been that it is “our culture”, but “our culture” seems to change from funeral to funeral, depending on who the undertakers and burial society are. One constant factor, however, seems to be a printed programme provided by the undertakers, and controlled by a master of ceremonies. The actual church service is fitted into the programme between the speeches. There will be a hymn, and then a slot for Revd X to do the funeral service. What is expected is a short exhortation, to be fitted in to a lot of other items, including clergy of several denominations, regardless of which church the deceased belonged to.

Philip Mabena’s funeral was different, and in its broad outline fitted the rubrics of the Orthodox burial service — it started with a vigil at the house, proceeded to the church for the service, and then to the cemetery for the burial.

This was only possible because Philip Mabena lived within walking distance of the church. Most Orthodox Christians in southern Africa live a long way from the church, and so the service usually satarts in the church, ot in other cases is held at the house, going from there to the cemetery.

At 7:00 am the body was brought out of the house after the vigil, and Deacon Enock Thobela, who is in charge of the Atteridgeville AOC parish, preceded it reading the sentences from the South Sotho Anglican Book of Common Prayer. The coffin was laid down near the gate, and a member of the family said a last farewell, as Philip Mabena’s body left home for the last time. An earthenware pot was thrown on the ground and smashed. The coffin was then put in the hearse abnd taken to the church, with clergy walking in front or alongside. The procession to the church was led by a brass band.

Funeral procession to African Orthodox Church in Atteridgeville.

At the church the service was led by Bishop Mogano from Krugersdorp, and there were a couple of other priests as well. I was interested to see that

they did the funeral the way we have done it, with the speeches and eulogies built into the service, instead of the other way round, as is often done in other services, where the burial societies and undertakers try to make the service a small part of a larger programme. Also I was the only non-AOC among the clergy — in other cases there are clergy representing the denominations that various members of the family belong to. This was very much an all AOC affair.

The brass band in the church

One of the speakers was Sejamotopo Charles Motau, the eldest son of Johannes Motau, a former priest of the church, who was a Member of Parliament for the Democratic Alliance, so his speech took on a political tinge, and politics was in the air, with the results of municipal elections still coming in.

Funeral of Philip Mabena

When we went to the cemetery, we gave a lift to one of the AOC priests, Don Dlwati from Tembisa, who was a son of the former archbishop of that branch of the AOC, Adonijah Dlwati. There was a huge traffic jam at the gates of the cemetery, which was in Lotus Gardens, over the railway line and the toll road.

Funeral of Philip Mabena, leaving the church after the service.

At the graveside, Bishop Mogano was very much in charge of the proceedings, telling which of the priests to say which prayers. As soon as they had filled in the grave, they laid the tombstone, and Bishop Mogano asked me to say a prayer at that point, so I sang “Memory Eternal” in North Sotho.

It was interesting also to see the gravestone laid and unveiled right after the burial. In many cases that takes place about a year after the burial, which means that the family has to go through the whole business of catering for visitors all over again.

As we walked back to the car I talked to the Programme Director, Mr P. Mahlangu, who was asking about the Orthodox Church and was puzzled by the epithets “Greek”, “Russian” and the like, and I explainede to him that we had Greek, Russian, Serbian and Romanian parishes, but it was one Orthodox Church. We returned to the house where there was food, and the brass band played some more.

Over brunch we chatted to Don Dlwati, who had travelled back with us too. I noticed that he was using Baptist and Methodist service books, presumably because the Anglican ones they prefer to use are no longer available. So once again I appeal to any Anglicans reading this, who have any copies of Southern Sotho Prayer Books that they would be willing to donate, to please get in touch with me.

For more information about the African Orthodox Church and its relation to canonical Orthodoxy, see here.